Women’s Usage Behavior and Perceived Usefulness with Using a Mobile Health Application for Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Mixed-Methods Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

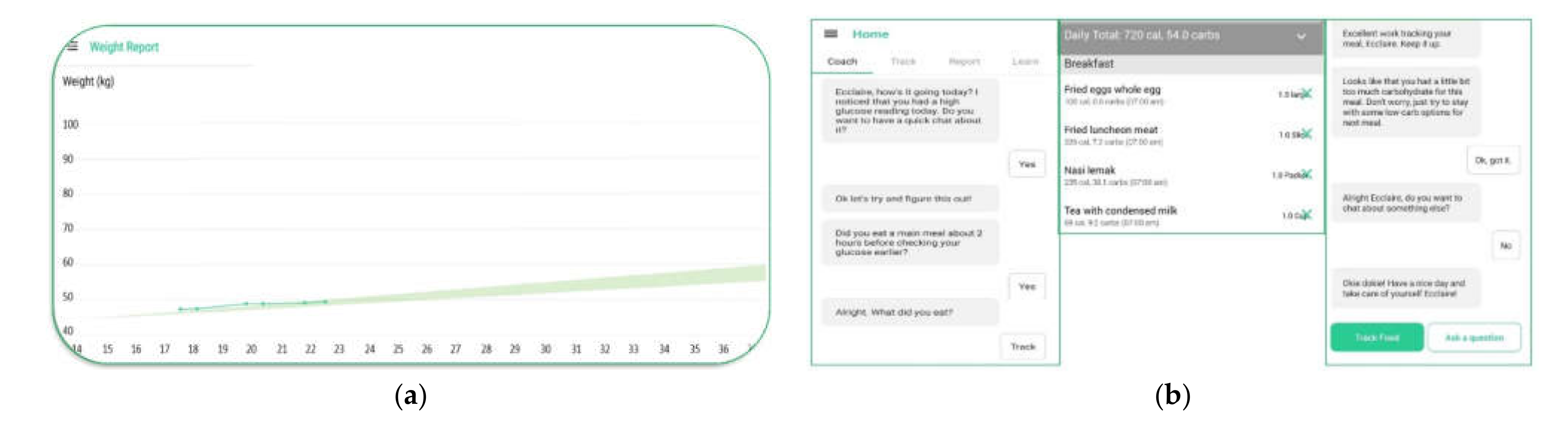

2.1. Habits-GDM Application Overview

2.2. Theory Used in the Design of the Habits-GDM Application

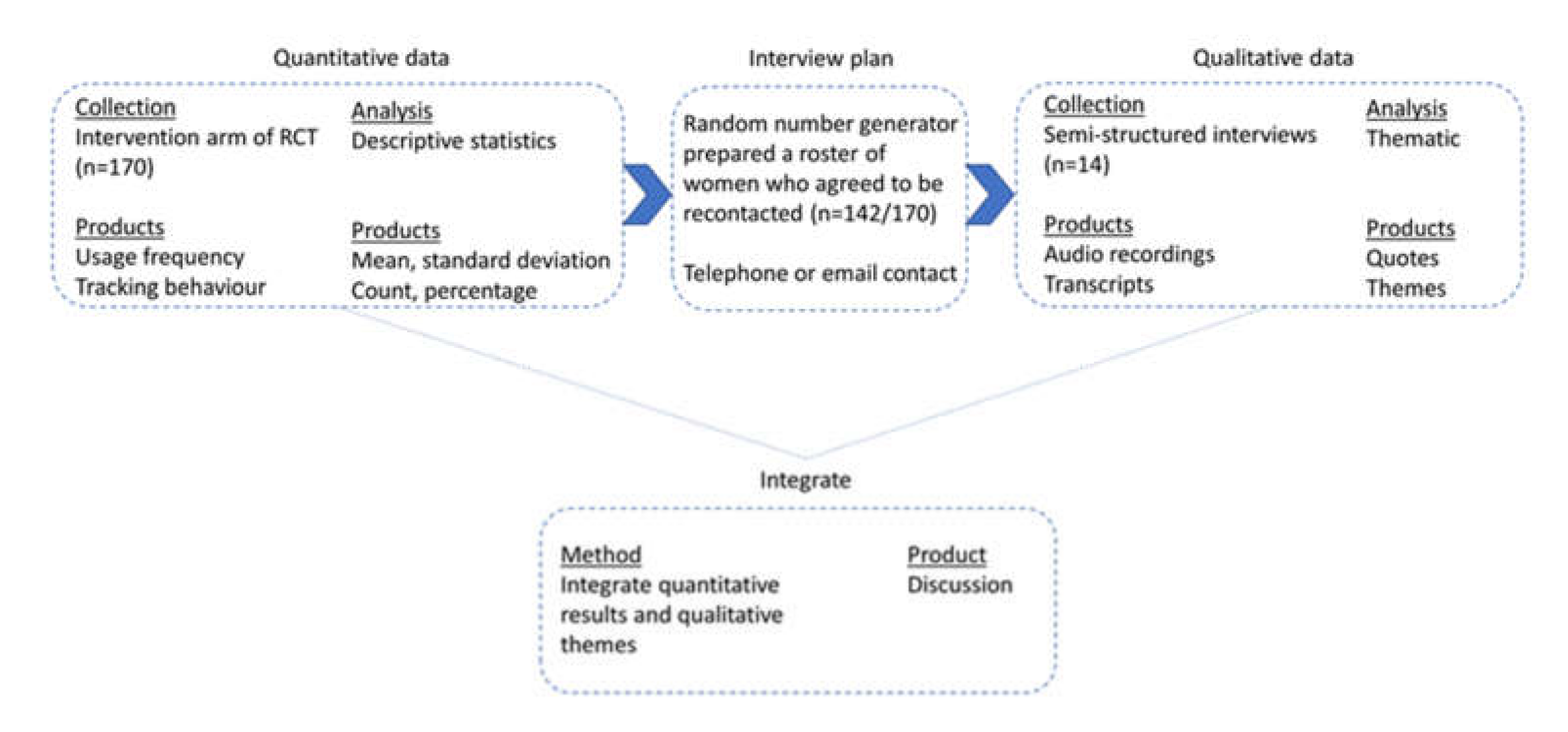

2.3. Study Design

2.3.1. Sampling and Data Collection—Quantitative Data

2.3.2. Sampling and Data Collection—Qualitative Data

2.4. Ethical Considerations

2.5. Data Management and Security

2.5.1. Data Analysis—Quantitative Data

2.5.2. Data Analysis—Qualitative Data

2.6. Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Data

3. Results

3.1. Themes

3.1.1. Use of Educational Lessons of Habits-GDM Application

Reasons Why Educational Lessons Were Useful and Less Useful

“The application information was basic. Whereas the information provided by the healthcare professional is detailed […] dietician had all the products on her shelf […] nurses even bought a bowl and showed us the amount that we could take […] application cannot replace them […]” (P14).

Reasons How Educational Lessons Were Useful and Less Useful

3.1.2. Diet Tracking Behavior with Habits-GDM Application

Reasons Why Diet Tracking Component Was Less Useful

“[…] the food options are not very localized. The common local food, like chicken rice, cannot be found.” (P08)

Reasons How Diet Tracking Component Was Useful

3.1.3. Weight Tracking Behavior with Habits-GDM Application

Reason Why Weight Tracking Component Was Useful

Reasons How Weight Tracking Component Was Useful

3.1.4. Use of Coach Component of Habits-GDM Application

Reasons for Using and Not Using the Coach Component

Reasons How Coach Component Was Useful

“The messages are always replayed and standard. Always they will say you have to lower your carbs. After a while, you get used to the messages.” (P07)

4. Discussion

Limitations and Strengths

5. Practical Implications of This Study

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hewage, S.; Audimulam, J.; Sullivan, E.; Chi, C.; Yew, T.W.; Yoong, J. Barriers to Gestational Diabetes Management and Preferred Interventions for Women with Gestational Diabetes in Singapore: Mixed Methods Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2020, 4, e14486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Diabetes Federation 2019: Diabetes Atlas, 9th ed.; International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. Available online: https://www.diabetesatlas.org/en/ (accessed on 29 July 2020).

- Yew, T.W.; Chi, C.; Chan, S.-Y.; Van Dam, R.M.; Whitton, C.; Lim, C.S.; Foong, P.S.; Fransisca, W.; Teoh, C.L.; Chen, J.; et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial to Evaluate the Effects of a Smartphone Application-Based Lifestyle Coaching Program on Gestational Weight Gain, Glycemic Control, Maternal, and Neonatal Outcomes in Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: The SMART-GDM Study. Diabetes Care 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waite, M.; Martin, C.; Franklin, R.; Duce, D.; Harrison, R.; Garcia-Mancilla, J.; Oser, S.; Da Silva, E. Human Factors and Data Logging Processes with the Use of Advanced Technology for Adults with Type 1 Diabetes: Systematic Integrative Review. JMIR Hum. Factors 2018, 5, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, H.; Chai, Y.; Dong, L.; Niu, W.; Zhang, P. Effectiveness and Appropriateness of MHealth Interventions for Maternal and Child Health: Systematic Review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018, 6, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Creber, R.M.M.; Maurer, M.S.; Reading, M.; Hiraldo, G.; Hickey, K.T.; Iribarren, S. Review and Analysis of Existing Mobile Phone Apps to Support Heart Failure Symptom Monitoring and Self-Care Management Using the Mobile Application Rating Scale (MARS). JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2016, 4, e74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO | Atlas of EHealth Country Profiles 2015: The Use of EHealth in Support of Universal Health Coverage. Available online: http://www.who.int/goe/publications/atlas_2015/en/ (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Mobile Penetration Rate. Available online: https://data.gov.sg/dataset/mobile-penetration-rate (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Hossain, I.; Lim, Z.Z.; Ng, J.J.L.; Koh, W.J.; Wong, P.S. Public Attitudes towards Mobile Health in Singapore: A Cross-Sectional Study. Mhealth 2018, 4, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, I.; Ang, Y.N.; Chng, H.T.; Wong, P.S. Patients’ Attitudes towards Mobile Health in Singapore: A Cross-Sectional Study. Mhealth 2019, 5, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, W.J.; Landman, A.; Zhang, H.; Bates, D.W. Beyond Validation: Getting Health Apps into Clinical Practice. NPJ Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pustozerov, E.; Popova, P.; Tkachuk, A.; Bolotko, Y.; Yuldashev, Z.; Grineva, E. Development and Evaluation of a Mobile Personalized Blood Glucose Prediction System for Patients with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018, 6, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miremberg, H.; Ben-Ari, T.; Betzer, T.; Raphaeli, H.; Gasnier, R.; Barda, G.; Bar, J.; Weiner, E. The Impact of a Daily Smartphone-Based Feedback System among Women with Gestational Diabetes on Compliance, Glycemic Control, Satisfaction, and Pregnancy Outcome: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 218, 453.e1–453.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, P.; Zhou, P.; Chen, L.-M.; Li, S.-Y. Evaluating the Effects of Mobile Health Intervention on Weight Management, Glycemic Control and Pregnancy Outcomes in Patients with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2019, 42, 709–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKillop, L.; Hirst, J.E.; Bartlett, K.J.; Birks, J.S.; Clifton, L.; Farmer, A.J.; Gibson, O.; Kenworthy, Y.; Levy, J.C.; Loerup, L.; et al. Comparing the Efficacy of a Mobile Phone-Based Blood Glucose Management System with Standard Clinic Care in Women with Gestational Diabetes: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018, 6, e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Ofi, E.A.; Mosli, H.H.; Ghamri, K.A.; Ghazali, S.M. Management of Postprandial Hyperglycaemia and Weight Gain in Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Using a Novel Telemonitoring System. J. Int. Med. Res. 2019, 47, 754–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgen, I.; Småstuen, M.C.; Jacobsen, A.F.; Garnweidner-Holme, L.M.; Fayyad, S.; Noll, J.; Lukasse, M. Effect of the Pregnant+ Smartphone Application in Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Randomised Controlled Trial in Norway. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e030884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maar, M.A.; Yeates, K.; Perkins, N.; Boesch, L.; Hua-Stewart, D.; Liu, P.; Sleeth, J.; Tobe, S.W. A Framework for the Study of Complex MHealth Interventions in Diverse Cultural Settings. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017, 5, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pludwinski, S.; Ahmad, F.; Wayne, N.; Ritvo, P. Participant Experiences in a Smartphone-Based Health Coaching Intervention for Type 2 Diabetes: A Qualitative Inquiry. J. Telemed Telecare 2016, 22, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritholz, M.D.; Beverly, E.A.; Weinger, K. Digging Deeper: The Role of Qualitative Research in Behavioral Diabetes. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2011, 11, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, A.; Shiffman, S.; Atienza, A.; Nebeling, L. Science of Real-Time Data Capture, the: Self-Reports in Health Research, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007; ISBN 978-0-19-517871-5. [Google Scholar]

- Runyan, J.D.; Steenbergh, T.A.; Bainbridge, C.; Daugherty, D.A.; Oke, L.; Fry, B.N. A Smartphone Ecological Momentary Assessment/Intervention “App” for Collecting Real-Time Data and Promoting Self-Awareness. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Becker, M.H.; Radius, S.M.; Rosenstock, I.M.; Drachman, R.H.; Schuberth, K.C.; Teets, K.C. Compliance with a Medical Regimen for Asthma: A Test of the Health Belief Model. Public Health Rep. 1978, 93, 268–277. [Google Scholar]

- Garnweidner-Holme, L.M.; Borgen, I.; Garitano, I.; Noll, J.; Lukasse, M. Designing and Developing a Mobile Smartphone Application for Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Followed-Up at Diabetes Outpatient Clinics in Norway. Healthcare 2015, 3, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pearce, E.E.; Evenson, K.R.; Downs, D.S.; Steckler, A. Strategies to Promote Physical Activity During Pregnancy: A Systematic Review of Intervention Evidence. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2013, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, I.M. Historical Origins of the Health Belief Model. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobile Health Applications in Workplace Health Promotion: An Integrated Conceptual Adoption Framework. Procedia Technol. 2014, 16, 1374–1382. [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Analytics Tools & Solutions for Your Business—Google Analytics. Available online: https://marketingplatform.google.com/about/analytics/ (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Jana Care. Jana Care; 2019. Available online: http://www.janacare.com/ (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Skar, J.B.; Garnweidner-Holme, L.M.; Lukasse, M.; Terragni, L. Women’s Experiences with Using a Smartphone App (the Pregnant+ App) to Manage Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in a Randomised Controlled Trial. Midwifery 2018, 58, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieffers, J.R.L.; Valaitis, R.F.; George, T.; Wilson, M.; Macdonald, J.; Hanning, R.M. A Qualitative Evaluation of the EaTracker® Mobile App. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jana Care, Inc. SEC Registration. Available online: https://sec.report/CIK/0001696563 (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software. QSR International. 2020. Available online: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo/home (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4833-1568-3. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, T.K.M.; Man, S.S.; Chan, A.H.S. Critical Factors for the Use or Non-Use of Personal Protective Equipment Amongst Construction Workers. Saf. Sci. 2020, 126, 104663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draucker, C.B.; Martsolf, D.S.; Ross, R.; Rusk, T.B. Theoretical Sampling and Category Development in Grounded Theory. Qual Health Res. 2007, 17, 1137–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J.M. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory: Procedures and Techniques, 1st ed.; Sage Publications: Newbuy Park, CA, USA, 1990; ISBN 978-0-7619-0748-0. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry, 1st ed.; Sage Publications: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1985; ISBN 978-0-8039-2431-4. [Google Scholar]

- Neale, J.; Miller, P.; West, R. Reporting Quantitative Information in Qualitative Research: Guidance for Authors and Reviewers. Addiction 2014, 109, 175–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Cathain, A.; Murphy, E.; Nicholl, J. Three Techniques for Integrating Data in Mixed Methods Studies. BMJ 2010, 341, c4587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnweidner-Holme, L.; Andersen, T.H.; Sando, M.W.; Noll, J.; Lukasse, M. Health Care Professionals’ Attitudes toward, and Experiences of Using, a Culture-Sensitive Smartphone App for Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Qualitative Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018, 6, e123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gwizdka, J.; Trace, C.B. Consumer Evaluation of the Quality of Online Health Information: Systematic Literature Review of Relevant Criteria and Indicators. JMIR 2019, 21, e12522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight-Agarwal, C.; Davis, D.L.; Williams, L.; Davey, R.; Cox, R.; Clarke, A. Development and Pilot Testing of the Eating4two Mobile Phone App to Monitor Gestational Weight Gain. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2015, 3, e44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reddy, G.; Van Dam, R.M. Food, Culture, and Identity in Multicultural Societies: Insights from Singapore. Appetite 2020, 149, 104633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Ngo, C.-W. Deep-Based Ingredient Recognition for Cooking Recipe Retrieval. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 15 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ming, Z.Y.; Chen, J.; Cao, Y.; Forde, C.; Ngo, C.W.; Chua, T.S. Food Photo Recognition for Dietary Tracking System and Experiment. In International Conference on Multimedia Modeling; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 129–141. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.-C.; Chen, C.-H.; Tsou, Y.-C.; Lin, Y.-S.; Chen, H.-Y.; Yeh, J.-Y.; Chiu, S.Y.-H. Evaluating Mobile Health Apps for Customized Dietary Recording for Young Adults and Seniors: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2019, 7, e10931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koot, D.; Goh, P.S.C.; Lim, R.S.M.; Tian, Y.; Yau, T.Y.; Tan, N.C.; Finkelstein, E.A. A Mobile Lifestyle Management Program (GlycoLeap) for Peaople with Type 2 Diabetes: Single-Arm Feasibility Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2019, 7, e12965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/advice/mib131/chapter/Summary. (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Nundy, S.; Dick, J.J.; Chou, C.-H.; Nocon, R.S.; Chin, M.H.; Peek, M.E. Mobile Phone Diabetes Project Led to Improved Glycemic Control and Net Savings for Chicago Plan Participants. Health Aff. 2014, 33, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulder, R.; Singh, A.B.; Hamilton, A.; Das, P.; Outhred, T.; Morris, G.; Bassett, D.; Baune, B.T.; Berk, M.; Boyce, P.; et al. The Limitations of Using Randomised Controlled Trials as a Basis for Developing Treatment Guidelines. Evid. Based Ment. Health 2018, 21, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Component | Description | Tracking Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Educational lessons | A total of 12 educational lessons on GDM 1 and self-management were delivered via a virtual coach. This curriculum was similar to the in-person education provided by the hospital’s usual care. It also contained additional modules on gestational weight gain. | Complete one lesson (lasting about 5–10 min) per day |

| Self-monitoring of blood glucose | Blood glucose measurements obtained using the Aina Mini glucometer (a novel hardware sensor that can be plugged into any smartphone) were automatically transferred into participants’ Habits-GDM application accounts. | Seven times a day for 2–3 days a week |

| Physical activity tracking | The Habits-GDM application tracks the number of daily steps taken using the participants’ built-in phone pedometers. | Planned physical activity of 30 min per day |

| Diet tracking | The food database takes reference from the Singapore Health Promotion Board’s Energy and Nutrient Composition of Food. Total calories and carbohydrates are the only two variables provided for each food. | At least three meals and two days per week |

| Weight tracking | Bluetooth-enabled weighing scale readings were automatically transferred to the application. Weight values are represented in a graphical, chart, or report format on the phone, in comparison to the ideal weight for baseline body mass index. | At least once a week |

| Coaching | An interactive messaging platform where participants are free to pose questions to the healthcare team who will respond in no more than 24 h. The healthcare team did not proactively approach the participants. Additionally, all participants receive health coaching via generic automated text messages on tips towards healthy behavior beneficial for GDM management. The food database was designed drawing from principals of ecological momentary interventions [21,22]. When the participant’s 2 h post-meal glucose readings were >6.6 mmol/L, they were cued through automated messages to record their diet in the preceding 2–4 h, maximizing ecological circumstances for real-time reflections and learning. | No recommendation provided |

| Theme | Subtheme | Code |

|---|---|---|

| Use of educational lessons of Habits-GDM application | Reasons why educational lessons were useful (9/14, 64%) and less useful (5/14, 36%) | Pictorial representation (6/9, 67%) |

| Short duration (6/9, 67%) | ||

| Easy to understand content (6/9, 67%) | ||

| All information in one place (3/9, 33%) | ||

| Basic content (3/5, 60%) | ||

| Already available information on website (2/5, 40%) | ||

| Reasons how educational lessons were useful (7/14, 50%) and less useful (9/14, 64%) | Easy to remember healthy foods (7/7,1 00%) | |

| Guided to make healthy food choices (7/7, 100%) | ||

| Tiredness during pregnancy (9/9, 100%) | ||

| Diet tracking behavior with Habits-GDM application | Reasons why diet tracking component was less useful (12/14, 86%) | Difficult search feature (3/12, 25%) |

| Limited food database (9/12, 75%) | ||

| Incomprehensible measurement unit (8/12, 67%) | ||

| Incorrectly worded food items (1/12, 8%) | ||

| Healthcare professionals’ favor for paper diary (12/12, 100%) | ||

| Reasons how diet tracking component was useful (2/14, 14%) | Sense of self control (2/2, 100%) | |

| Sense of confidence (2/2, 100%) | ||

| Weight tracking behavior with Habits-GDM application | Reasons why weight tracking component was useful (9/14, 64%) | Ease of use (9/9, 100%) |

| Graphical representation (7/9, 78%) | ||

| Reasons how weight tracking component was useful (9/14, 64%) | Increased self-awareness (7/9, 78%) | |

| Use of coach component of Habits-GDM application | Reasons for using (10/14, 71%) and not using the coach component (4/14, 29%) | Logistic issues (10/10, 100%) |

| Alternate modes to contact healthcare professionals (2/4, 50%) | ||

| Healthcare professionals’ lack of direct access to dashboard (2/4, 50%) | ||

| Reasons how coach component was useful (6/14, 43%) | Immediate sense of self-awareness in food choices (5/6, 83%) | |

| Usefulness temporary due to same messages (5/6, 83%) |

| Themes | User Perception | Construct | Suggestion for Potential Improvement to Enhance Application Usage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Use of educational lessons | All information in one place facilitated GDM 1 control | Perceived benefit | Increase convenience to access anytime |

| Diet tracking behavior | Low ease of use hindered tracking diet | Perceived barrier | Increase robustness of application component by incorporating local food with the commonly used local name |

| Tracking generated confidence in food choices | Self-efficacy | To provide side-by-side display of diet data and blood glucose levels for patients to correlate | |

| Weight tracking behavior | Weight, not a priority, hindered tracking weight | Perceived benefit | Enhance focus on the benefit of recommended gestational weight gain to reduce the risk of perinatal morbidity |

| Weight monitored at consultation hindered tracking weight | Cues to action | Application to provide suggestions and cues to specific actions if patients are going off track and healthcare professionals to use and rely on application’s data | |

| Risk to baby facilitated tracking weight | Perceived benefit | Enhance focus on the benefit of recommended gestational weight gain to reduce the risk of perinatal morbidity | |

| High ease of use facilitated tracking weight | Perceived benefit | Increase robustness of application component | |

| Use of coach component | Automated messages created an immediate sense of self-awareness in food choices | Self-efficacy | Increase robustness of application component |

| Repetitive automated message content’s usefulness was temporary | Perceived benefit | Specific messages with specific actions when patients go off track or vary the language of the same message so that it is not too ‘automated’ | |

| Healthcare professionals’ lack of access to dashboard prevented users from sending messages | Perceived barrier | Healthcare professionals to have access to the application and provide coaching | |

| Messages considered judgmental prevented users from sending messages | Self-efficacy Cues to action | Specific messages with specific actions when patients go off track and build specific cues to replace foods that are associated with high glucose to those with low glucose |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Surendran, S.; Lim, C.S.; Koh, G.C.H.; Yew, T.W.; Tai, E.S.; Foong, P.S. Women’s Usage Behavior and Perceived Usefulness with Using a Mobile Health Application for Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Mixed-Methods Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6670. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126670

Surendran S, Lim CS, Koh GCH, Yew TW, Tai ES, Foong PS. Women’s Usage Behavior and Perceived Usefulness with Using a Mobile Health Application for Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Mixed-Methods Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(12):6670. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126670

Chicago/Turabian StyleSurendran, Shilpa, Chang Siang Lim, Gerald Choon Huat Koh, Tong Wei Yew, E Shyong Tai, and Pin Sym Foong. 2021. "Women’s Usage Behavior and Perceived Usefulness with Using a Mobile Health Application for Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Mixed-Methods Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 12: 6670. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126670

APA StyleSurendran, S., Lim, C. S., Koh, G. C. H., Yew, T. W., Tai, E. S., & Foong, P. S. (2021). Women’s Usage Behavior and Perceived Usefulness with Using a Mobile Health Application for Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Mixed-Methods Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6670. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126670