A New Swiss Federal Act on Gambling: From Missed Opportunities towards a Public Health Approach?

Abstract

1. Context

2. Evolution of an Approach towards Prevention in the New Law

3. Social Measures Programs

4. Cantonal Level Interventions

5. Other Prevention-Related Provisions

6. Limitations of the LJAr

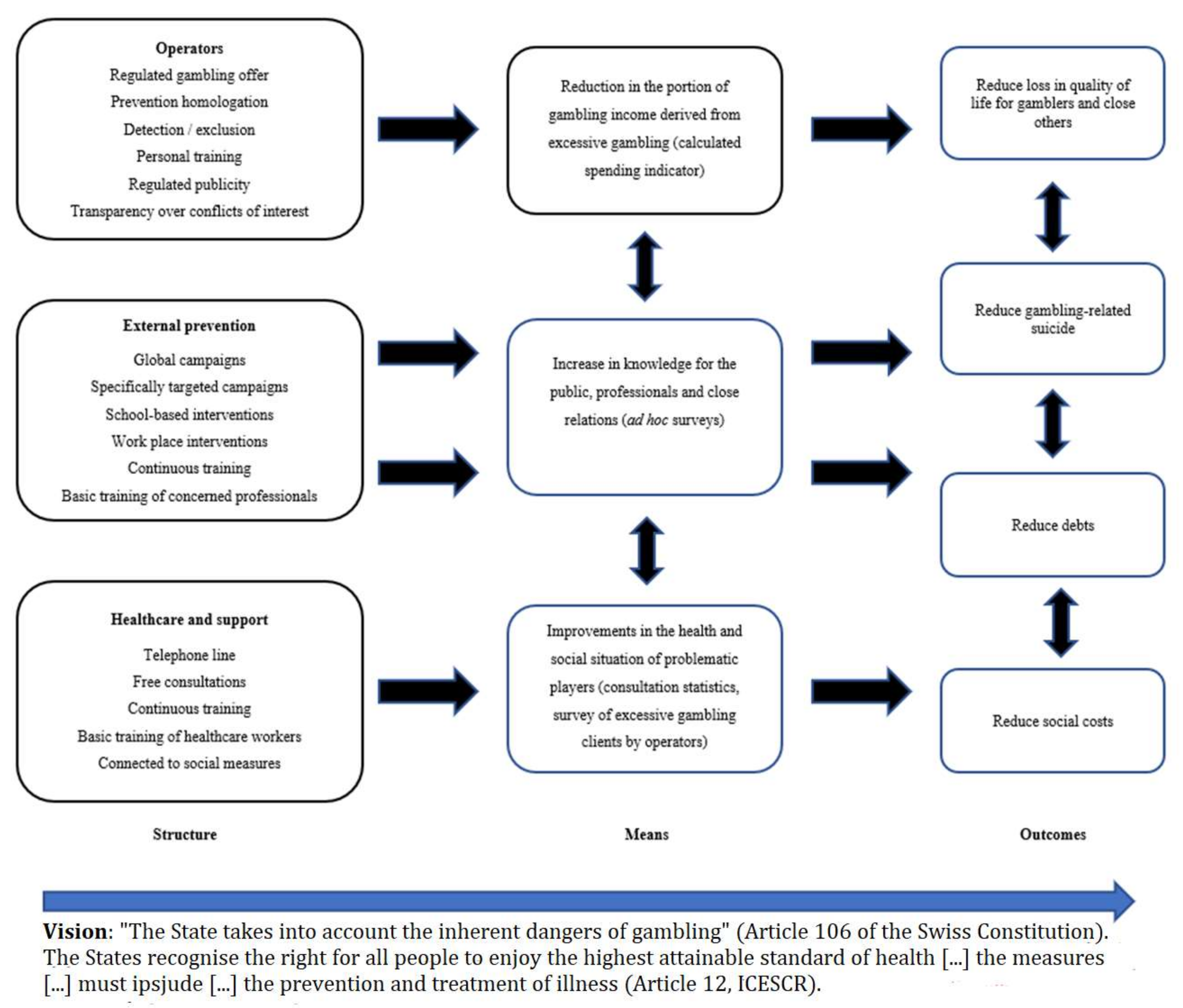

7. Method for Identifying Actors and Drafting an Impact Model

8. Observations

8.1. Institutional Actors

8.2. Impact Model

9. Discussion and Conclusions

9.1. Summary

9.2. Indicator Availability and Accessibility

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hodgins, D.C.; Petry, N.M. The World of Gambling: The National Gambling Experiences Series: Editorial. Addiction 2016, 111, 1516–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livingstone, C.; Rintoul, A. Moving on from Responsible Gambling: A New Discourse Is Needed to Prevent and Minimise Harm from Gambling. Public Health 2020, 184, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, P.; Raeburn, J.; De Silva, K. A question of balance: Prioritizing public health responses to harm from gambling. Addiction 2009, 104, 688–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowden-Jones, H.; Dickson, C.; Dunand, C.; Simon, O. Harm Reduction for Gambling: A Public Health Approach; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-0-429-95584-6. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, P.J.; Rossen, F. A Tale of Missed Opportunities: Pursuit of a Public Health Approach to Gambling in New Zealand: Gambling and Public Health in New Zealand. Addiction 2012, 107, 1051–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billieux, J.; Achab, S.; Savary, J.-F.; Simon, O.; Richter, F.; Zullino, D.; Khazaal, Y. Gambling and Problem Gambling in Switzerland: Gambling in Switzerland. Addiction 2016, 111, 1677–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichenberger, Y.; Rihs-Middel, M. Jeu de Hasard: Comportement et Problématique En Suisse; FERARIHS Suisse: Villars-sur-Glâne, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dey, M.; Haug, S. Glücksspiel: Verhalten und Problematik in der Schweiz Im Jahr 2017; ISGF: Zürich, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jeanreneaud, C.; Gay, M.; Kohler, D.; Simon, O. The Social Cost of Excessive Gambling. In Harm Reduction for Gambling: A Public Health Approach; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; p. 23. ISBN 978-0-429-95584-6. [Google Scholar]

- Wardle, H.; Reith, G.; Best, D.; McDaid, D.; Platt, S. Measuring Gambling-Related Harms: A Framework for Action; Gambling Commission: Birmingham, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Confédération Suisse. Loi Fédérale Sur Les Jeux d’argent (LJAr) Du 29 Septembre; RS 935.51 (État Le 1er Juillet 2019). Available online: https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/cc/2018/795/fr (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- Jäggi, J.; Künz, K.; Gehrig, M. Indikatoren-Set Zur Strategie Sucht; Bundesamt für Gesundheit: Bern, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- FOPH. National Strategy on Addiction. Available online: https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/en/home/strategie-und-politik/nationale-gesundheitsstrategien/strategie-sucht.html (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- Confédération Suisse. Loi Fédérale Du 18 Décembre 1998 Sur Les Jeux de Hasard et Les Maisons de Jeu (Loi Sur Les Maisons de Jeu, LMJ); RS 935.52 (État Le 27 Décembre 2006). Available online: https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/cc/2000/118/fr (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- Confédération Suisse. Ordonnance Du 23 Février 2000 Sur Les Jeux de Hasard et Les Maisons de Jeu (Ordonnance Sur Les Maisons de Jeu, OLMJ). RS 935.521 (État Le 10 Décembre 2002). Available online: https://www.bing.com/search?q=Conf%C3%A9d%C3%A9ration+Suisse.+Ordonnance+du+23+f%C3%A9vrier+2000+sur+les+jeux+de+hasard+et+les+maisons+de+jeu+(Ordonnance+sur+les+maisons+de+jeu%2C+OLMJ).+RS+935.521+(%C3%89tat+le+10+d%C3%A9cembre+2002).&cvid=ac79fbbc7ec34916bfed4f92c043316b&aqs=edge...69i57.1341j0j1&pglt=299&FORM=ANNTA1&PC=U531 (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- CILP. Conférence Spécialisée Sur Le Marché Des Loteries et La Loi Sur Les Loteries. Convention Intercantonale Sur La Surveil-lance, l’autorisation et La Répartition Du Bénéfice de Loteries et Paris Exploités Sur Le Plan Intercantonal Ou Sur l’ensemble de La Suisse (CILP). 2005. Available online: https://lex.vs.ch/app/fr/texts_of_law/935.51-1 (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- Confédération Suisse. Ordonnance Sur Les Jeux D’argent (OJAr) du 7 Novembre 2018 Le, vu la loi du 29 Septembre 2017 Sur Les Jeux D’argent (LJAr). Available online: https://www.bing.com/search?q=OJAR+Ordonnance&cvid=c26047de79554d0588d61ba41daefd77&aqs=edge..69i57.298j0j1&pglt=299&FORM=ANSPA1&PC=U531 (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- Simon, O.; Peduzzi, F.; Savary, J.-F.; Jeannot, E. Nouvelle loi suisse sur les jeux d’argent: Incidences pour la prévention. Alcoologie Addictologie 2020, 42, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Notari, L.; Gmel, G.; Kuendig, H. Développement D‘un Modèle de Monitorage Des Problèmes Liés Aux Jeux de Hasard et D‘argent En Suisse; Addiction Suisse: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Costes, J.M. A logical framework for the evaluation of a harm reduction policy for gambling. In Harm Reduction for Gambling: A Public Health Approach; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; p. 143. ISBN 978-0-429-95584-6. [Google Scholar]

- Nadeau, L.; Dufour, M.; Guay, R.; Kairouz, S.; Menard, J.M.; Paradis, C. Online Gambling: When the Reality of the Virtual Catches up with Us. Report of the Working Group on Online Gambling; Working Group on Online Gambling: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- UN General Assembly. International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. United Nations, Treaty Series. 16 December 1966, Volume 993, p. 3. Available online: Https://Www.Refworld.Org/Docid/3ae6b36c0.Html (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- Confédération Suisse. Constitution Fédérale de La Confédération Suisse Du 18 Avril 1999 (Etat Le 1er Janvier 2021). Available online: https://www.admin.ch/opc/en/classified-compilation/19995395/index.html (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- Blanco, C.; Blaszczynski, A.; Clement, R.; Derevensky, J.; Goudriaan, A.E.; Hodgins, D.C.; van Holst, R.J.; Ibáñez, Á.; Martins, S.S.; Moersen, C. Assessment Tool to Measure and Evaluate the Risk Potential of Gambling Products, ASTERIG: A Global Validation. Gaming Law Rev. Econ. 2013, 17, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, R. Fair Game? Producing and Publishing Gambling Research. Int. Gambl. Stud. 2014, 14, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockloff, M.J.; Hing, N. The Impact of Jackpots on EGM Gambling Behavior: A Review. J. Gambl. Stud. 2013, 29, 775–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Actor | Description |

|---|---|

| Operators | 21 land-based casinos; 2 public societies for lottery and sports betting (Loterie Romande and Swisslos); private establishments licensed by the confederation |

| State surveillance authorities | Commission fédérale des maisons de jeu (CFMJ) and Gespa |

| State Services | Other federal and cantonal administration services concerned by gambling (economic, financial, legal, and healthcare services) |

| Prevention and treatment services | Non-governmental organizations and other specialized centers for prevention/treatment |

| People who gamble | Individuals (currently no group representation) |

| Beneficiaries | Societies and organizations for sports, social projects, and culture benefitting from gambling revenue |

| Targeted Elements | Indicators | Sources | Effective Accessibility | Priority | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural indicators | Operators | Regulated offer | Law/ordinances/regulations; economic data on offers | Regulators | Some difficulties | High |

| Standardized prevention | Motivations for regulator decisions/ASTERIG grid or equivalent | Regulators | Extremely difficult | High | ||

| Detection/exclusion | Activity reports | Operators | Some difficulties | Medium | ||

| Training of Personnel | Activity reports | Operator service providers | Some difficulties | Low | ||

| Limiting advertising | Adverts detected as problematic | Media/prevention experts | Extremely difficult | High | ||

| Transparency over conflicts of interest | Mechanisms for personal remuneration | Testimonials | Extremely difficult | High | ||

| External prevention | Universal campaigns | Structured concept existing at cantonal/intercantonal level | Intercantonal program | Easy | Low | |

| Targeted campaigns | Concept existing by canton/intercantonal level with identified groups | Intercantonal program | Some difficulties | Medium | ||

| School interventions | Each cantonal education service has integrated a concept | Cantonal education minister | Some difficulties | High | ||

| Workplace interventions | Ad hoc survey of business panel: N with concept | Professional organizations | Some difficulties | Medium | ||

| Ongoing training | N existing training offers/N people trained | Professional organizations | Some difficulties | High | ||

| Basic training of concerned professions | Explicit objectives in training program catalogs/N dedicated hours | Specialized colleges/faculties | Some difficulties | High | ||

| Support and healthcare | Telephone line | N flyers/N posters/N website consultation/N actual calls | Gespa | Easy | Medium | |

| Free consultations | N places/N consultations | Gespa | Easy | High | ||

| Ongoing training | N existing training offers/N people trained | Professional organizations | Some difficulties | High | ||

| Basic training of socio-health employees | Explicit objectives of training/N dedicated hours | Specialized colleges/faculties | Some difficulties | High | ||

| Adequate remuneration for stakeholders | Average remuneration/related fields—turnover of teams | Specialized services | Extremely difficult | Medium | ||

| Coordination with social measures | Existing ad hoc service contracts under the regulatory authority | Operators/regulators | Some difficulties | High | ||

| Process indicators | Contribution of gambling dependent players to gambling revenue | (a) Gambling session data | Operators Social support (Enquête suisse sur la santé; ESS) | (a) Extremely difficult | High | |

| (b) Data from prevalence studies | (b) Easy | Medium | ||||

| Public knowledge | Representation survey/5–7 years (possibly online) | Agent/competition | Some difficulties | Medium | ||

| Knowledge of those close to excessive gamblers | Representation survey/5–7 years (possibly online) | Agent/competition | Some difficulties | High | ||

| Knowledge of professionals | Representation survey/5–7 years (possibly online) | Specialized colleges/faculties | Some difficulties | High | ||

| Operator use of social measures | Coverage rate/input–output form | Operators | Some difficulties | Medium | ||

| Use of specialized consultations | Coverage rate/input–output form | Support services | Some difficulties | Medium | ||

| Use of primary care medical services | Proportion of problem gamblers among clients/who broached the subject | General medical personnel | Some difficulties | High | ||

| Use of primary social care services | Proportion of problem gamblers among clients/who broached the subject | Social services | Some difficulties | High | ||

| Health status of people who problem gamble | Proportion of comorbidities among problem gamblers identified in Swiss Health Survey (ESS) versus those seeking support versus gambling venue clients | Social services + healthcare support services + gambling venues | Some difficulties | |||

| Outcome indicators | Decreased loss of quality of life for people close to those who problem gamble | Ad hoc survey every 10 years | ESS | Extremely difficult | Medium | |

| Decreased loss of quality of life for people who problem gamble | Ad hoc survey every 10 years | ESS | Extremely difficult | Medium | ||

| Reduced social costs | Ad hoc survey every 10 years | ESS | Extremely difficult | Medium | ||

| Decrease in gambling-related suicides | Survey of emergencies and specialized units Survey of problem-gambling clients at gaming locations | Healthcare services + Gambling venues | Extremely difficult | High | ||

| Decrease in debt for people who problem gamble | Statistics from healthcare services Debt support service survey Survey of problem-gambling clients at gambling venues | Healthcare services + social services | Some difficulties | High |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dickson, C.; Jeannot, E.; Peduzzi, F.; Savary, J.-F.; Costes, J.-M.; Simon, O. A New Swiss Federal Act on Gambling: From Missed Opportunities towards a Public Health Approach? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6575. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126575

Dickson C, Jeannot E, Peduzzi F, Savary J-F, Costes J-M, Simon O. A New Swiss Federal Act on Gambling: From Missed Opportunities towards a Public Health Approach? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(12):6575. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126575

Chicago/Turabian StyleDickson, Cheryl, Emilien Jeannot, Fabio Peduzzi, Jean-Félix Savary, Jean-Michel Costes, and Olivier Simon. 2021. "A New Swiss Federal Act on Gambling: From Missed Opportunities towards a Public Health Approach?" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 12: 6575. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126575

APA StyleDickson, C., Jeannot, E., Peduzzi, F., Savary, J.-F., Costes, J.-M., & Simon, O. (2021). A New Swiss Federal Act on Gambling: From Missed Opportunities towards a Public Health Approach? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6575. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126575