The Effect of Women’s Empowerment in the Utilisation of Family Planning in Western Ethiopia: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach

Abstract

1. Background

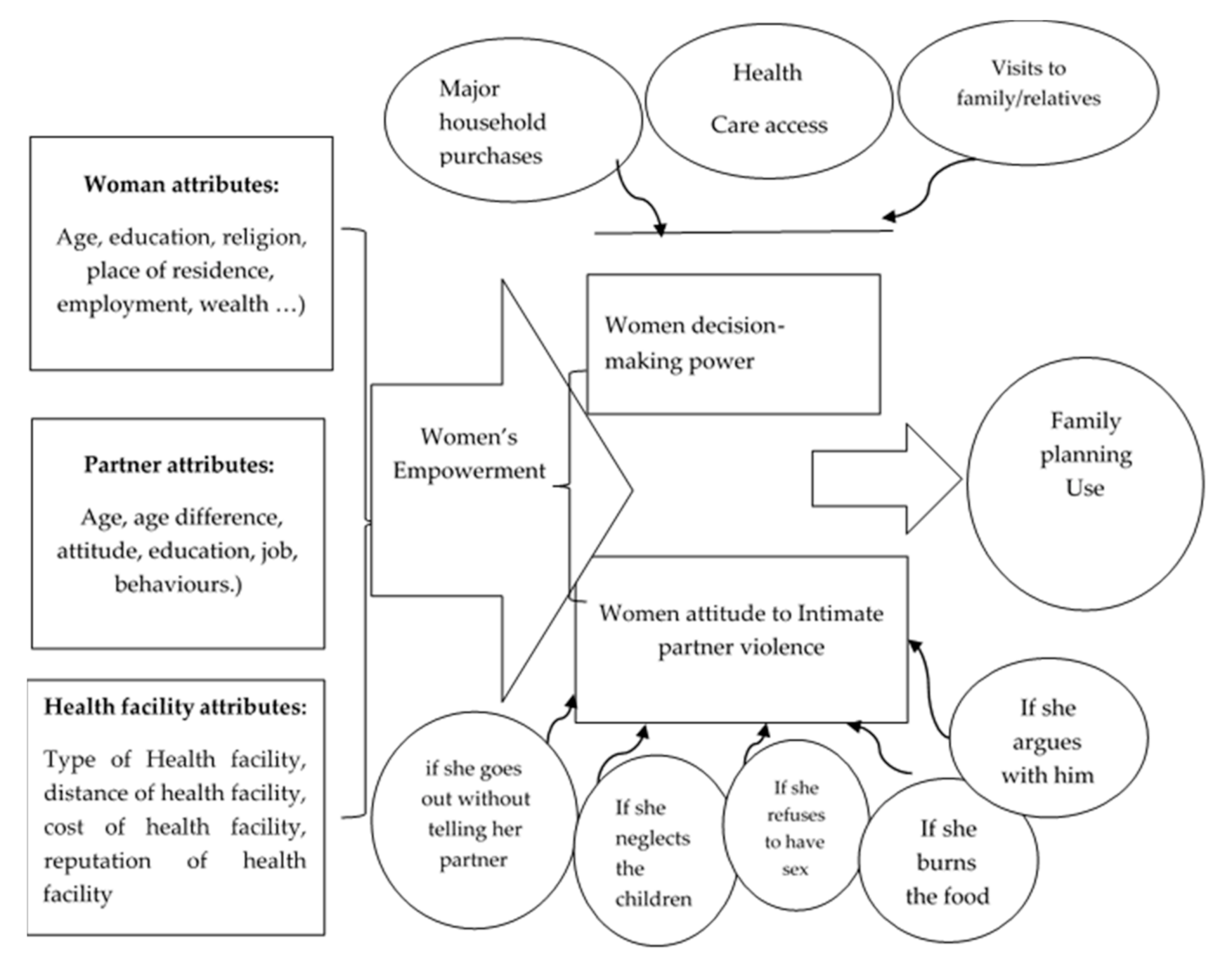

Research Hypothesis

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Design, Population and Setting

2.2. Sample and Sampling Procedure

2.3. Data Collection and Measurement Tools

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Operational Definitions

3. Results

3.1. Background Characteristics of the Study Respondents

3.2. Age at First Marriage and Birth

3.3. Family Planning Utilisation

3.4. Participation in Major Household Decisions

3.5. Attitudes towards Violence

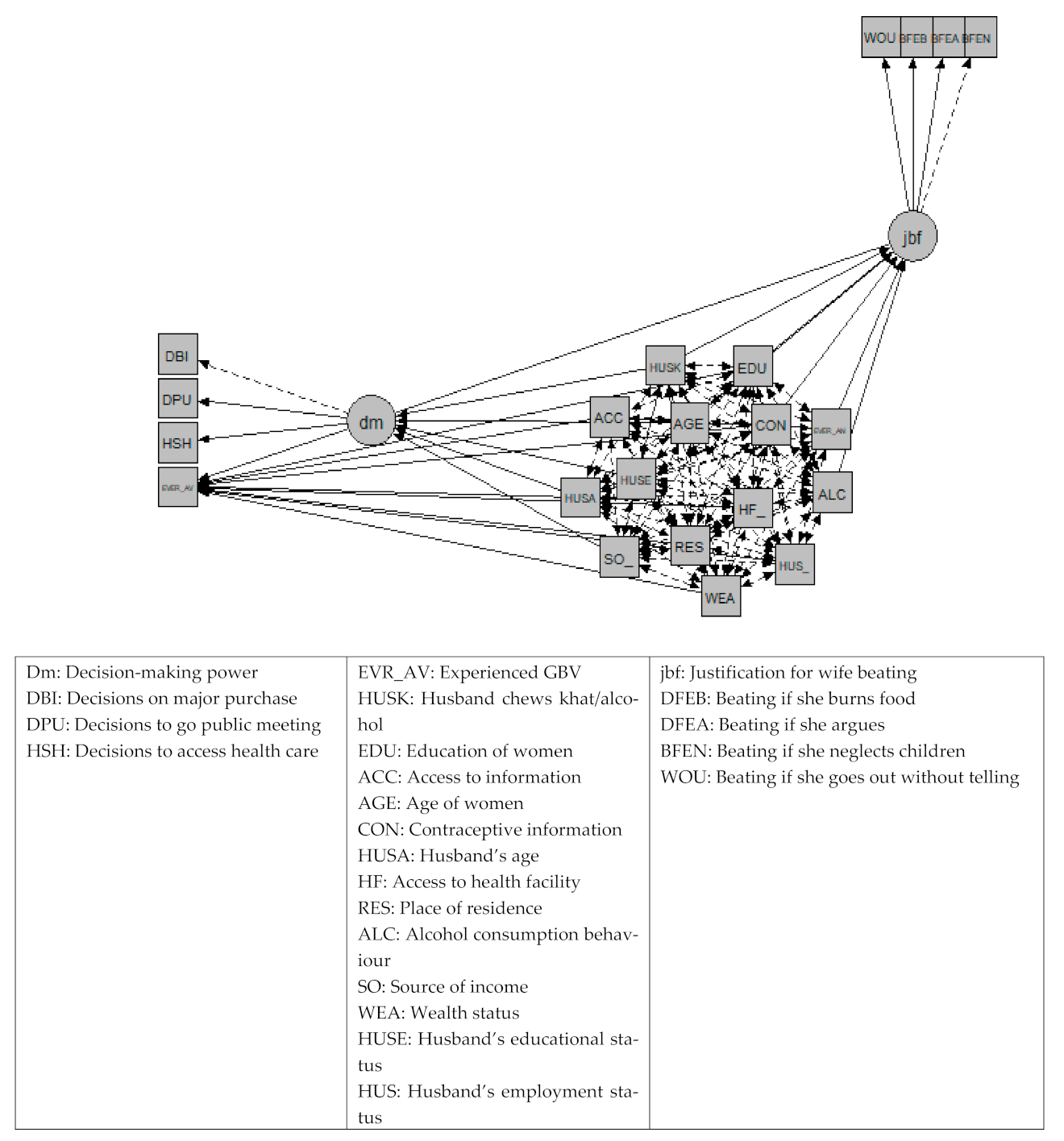

3.6. Factor Analysis (CFA) Results

3.7. Structural Equation Modelling Results (SEM)

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

4.2. Conclusion and Recommendations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Barros, A.J.; Ronsmans, C.; Axelson, H.; Loaiza, E.; Bertoldi, A.D.; França, G.V.; Bryce, J.; Boerma, J.T.; Victora, C. Equity in maternal, newborn, and child health interventions in Countdown to 2015: A retrospective review of survey data from 54 countries. Lancet 2012, 379, 1225–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborn, D.; Cutter, A.; Ullah, F. Universal Sustainable Development Goals: Understanding the Transformational Challenge for Developed Countries: STAKEHOLDER FORUM. 2015. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/1684SF_-_SDG_Universality_Report_-_May_2015.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- Women, U. Gender Equality: Why It Matters? Nework United Nations UN. 2019. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/5_Why-It-Matters-2020.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- Muluneh, M.; Francis, L.; Agho, K.; Stulz, V. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Associated Factors of Gender-Based Violence against Women in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. Achieving Gender Equality, Women’s Empowerment and Strengthening Development Cooperation Nework: Department of Economic and Social Affairs Office for ECOSOC Support and Coordination. 2010. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/ecosoc/docs/pdfs/10-50143_ (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- World Bank Group. World Development Report 2012: Gender Equality and Development; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/4391 (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- Dessalegn, M.; Ayele, M.; Hailu, Y.; Addisu, G.; Abebe, S.; Solomon, H.; Mogess, G.; Stulz, V. Gender inequality and the sexual and reproductive health status of young and older women in the Afar region of Ethiopia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Making Fair Choices on the Path to Universal Health Coverage. Final Report of the Who Consultative Group on Equity and Universal Health Coverage; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; Available online: https://www.who.int/choice/documents/making_fair_choices/en/ (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Varkey, P.; Kureshi, S.; Lesnick, T. Empowerment of women and its association with the health of the community. J. Women’s Health 2010, 19, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muluneh, M.D.; Stulz, V.; Francis, L.; Agho, K. Gender based violence against women in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bongaarts, J.; Cleland, J.C.; Townsend, J.; Bertrand, J.T.; Gupta, M.D. Family Planning Programs for the 21st Century: Rationale and Design; Population Council: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Available online: https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/departments_sbsr-rh/1001/ (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Corroon, M.; Speizer, I.S.; Fotso, J.-C.; Akiode, A.; Saad, A.; Calhoun, L.; Irani, L. The Role of Gender Empowerment on Reproductive Health Outcomes in Urban Nigeria. Matern. Child Health J. 2014, 18, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UKAID. Empowerment: A journey not a destination. Pathw. Women Empower. J. 2006, 41. Available online: https://www.participatorymethods.org/sites/participatorymethods.org/files/PathwaysSynthesisReport_0.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Partners in Population and Development, Editor Women’s Empowerment and Gender Equality. promoting women’s empowerment for better health outcomes for women and children. In Proceedings of the Strategy Brief for the Inter Ministerial Conference on “South-South Cooperation in Post ICDP and MDGs”, Beijing, China, 16 June 2013.

- Muluneh, M.D.; Francis, L.; Agho, K.; Stulz, V. Mapping of intimate partner violence: Evidence from a national population survey. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muluneh, M.D.; Alemu, Y.W.; Meazaw, M.W. Geographic variation and determinants of help seeking behaviour among married women subjected to intimate partner violence: Evidence from national population survey. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darroch, J.E.; Sedgh, G.; Ball, H. Contraceptive Technologies: Responding to Women’s Needs; Guttmacher Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2011; Volume 201, pp. 1–51. [Google Scholar]

- Habumuremyi, P.D.; Zenawi, M. Making family planning a national development priority. Lancet 2012, 380, 78–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigzaw, M.; Zakus, D.; Tadesse, Y.; Desalegn, M.; Fantahun, M. Paving the way for universal family planning coverage in Ethiopia: An analysis of wealth related inequality. Int. J. Equity Health 2015, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adebowale, S.A.; Adedini, S.A.; Ibisomi, L.D.; Palamuleni, M.E. Differential effect of wealth quintile on modern contraceptive use and fertility: Evidence from Malawian women. BMC Women’s Health 2014, 14, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, R.H. The Role of Family Planning in Poverty Reduction. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 110, 999–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPHI; MOH; DHS-ICF; Mini EDHS. Key Indicators Addis Ababa. 2019. Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/PR120/PR120.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2021).

- FDRE. Health Policy for Ethiopia; Transitional Government of Ethiopia: Addis Ababa, Ethopia, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Central Statistics Agency of Ethiopia, ICF. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016; CSA: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; ICF: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hameed, W.; Azmat, S.K.; Ali, M.; Sheikh, M.I.; Abbas, G.; Temmerman, M. Women’s empowerment and contraceptive use: The role of independent versus couples’ decision-making, from a lower middle income country perspective. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayan, D. Empowerment and Poverty Reduction; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra, A.; Schuler, S.R.; Boender, C. Measuring women’s empowerment as a variable in international development. In Background Paper Prepared for the World Bank Workshop on Poverty and Gender: New Perspectives; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Haque, M.; Islam, T.M.; Tareque, M.I.; Mostofa, M. Women empowerment or autonomy: A comparative view in Bangladesh context. Bangladesh E J. Sociol. 2011, 8, 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- DHS. Women’s Empowerment: DHS. Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/data/Guide-to-DHS-Statistics/index.htm#t=15_Women%E2%80%99s_Empowerment.htm (accessed on 24 May 2021).

- Pett, M.A.; Lackey, N.R.; Sullivan, J.J. Making Sense of Factor Analysis: The Use of Factor Analysis for Instrument Development in Health Care Research; SAGE: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, J.P. Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pratley, P. Associations between quantitative measures of women’s empowerment and access to care and health status for mothers and their children: A systematic review of evidence from the developing world. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 169, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaya, S.; Uthman, O.A.; Ekholuenetale, M.; Bishwajit, G. Women empowerment as an enabling factor of contraceptive use in Sub-Saharan Africa: A multilevel analysis of cross-sectional surveys of 32 countries. Reprod. Health 2018, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, D.K.; Niehof, A. Women’s autonomy and husbands’ involvement in maternal health care in Nepal. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 93, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemayehu, Y.K.; Theall, K.; Lemma, W.; Hajito, K.W.; Tushune, K. The role of empowerment in the association between a woman’s educational status and infant mortality in Ethiopia: Secondary analysis of demographic and health surveys. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 2015, 25, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wai, M.M.; Bjertness, E.; Stigum, H.; Htay, T.T.; Liabsuetrakul, T.; Moe Myint, A.N.; Sundby, J. Unmet need for family planning among urban and rural married women in Yangon Region, Myanmar—A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wai, M.M.; Bjertness, E.; Htay, T.T.; Liabsuetrakul, T.; Myint, A.N.M.; Stigum, H.; Sundby, J. Dynamics of contraceptive use among married women in North and South Yangon, Myanmar: Findings from a cross-sectional household survey. Contracept. X 2020, 2, 100015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babiarz, K.I.; Miller, G.; Valente, C. Family Planning and Women’s Economic Empowerment: Incentive Effects and Direct Effects among Malaysian Women; Center for Global Development Working Paper: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sedgh, G.; Ashford, L.S.; Hussain, R. Unmet Need for Contraception in Developing Countries: Examining Women’s Reasons for Not Using a Method; Guttmacher Institute: New Work, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Educational status of women | ||

| Illiterate | 386 | 51.70 |

| Primary (1–8) | 276 | 37.00 |

| Low secondary (9–10) | 62 | 8.30 |

| Secondary and above | 22 | 3.00 |

| Partner education status | ||

| Illiterate | 299 | 40.08 |

| Primary (1–8) | 355 | 47.59 |

| Low secondary (9–10) | 55 | 7.37 |

| Secondary and above | 37 | 4.96 |

| Employment | ||

| Not employed | 701 | 93.97 |

| Employed | 45 | 6.03 |

| Religious denomination | ||

| Muslim | 723 | 96.92 |

| Christian | 23 | 3.08 |

| Main source of income for the family | ||

| Land cultivation | 454 | 60.86 |

| Small business | 137 | 18.36 |

| Husbandry | 102 | 13.67 |

| Paid job | 26 | 3.49 |

| Labour | 23 | 3.08 |

| Other | 4 | 0.53 |

| Access to sources of information | ||

| Yes | 469 | 62.87 |

| No | 277 | 37.13 |

| Have You Ever Given Birth? | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 723 | 96.92 | |

| No | 23 | 3.08 | |

| How many children do you have in your life (both alive and dead)? | Mean | Median | SD |

| 4.02 | 4.00 | 2.44 | |

| Total number of children alive | 3.63 | 3.00 | 2.22 |

| Birth interval | Frequency | Percentage | |

| One year | 125 | 16.76 | |

| Two years | 220 | 29.49 | |

| Three years | 245 | 32.84 | |

| Four years | 79 | 10.59 | |

| More than four years | 54 | 7.24 | |

| Does your husband/partner have another partner? | |||

| No | 637 | 85.39 | |

| Yes | 109 | 14.61 | |

| Decision-Making Dimension (N = 746) | Joint or Alone Percent | Husband or Someone Else (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | In your household who usually makes decisions about large household purchases | 68.23 | 31.77 |

| 2 | In your household who usually decides to visit your family, relatives | 24.26 | 75.74 |

| 3 | In your household who usually makes decisions about the health care of the women | 19.84 | 80.16 |

| Indicator | Yes (%) | No (%) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In your opinion, is a husband justified in physical violence towards his wife in the following situations: | ||||

| 1 | If she goes out without telling him? | 66.62 | 33.38 | 100 |

| 2 | If she neglects the children? | 58.71 | 41.29 | 100 |

| 3 | If she argues with him? | 52.55 | 47.45 | 100 |

| 4 | If she refuses to have sex with him? | 40.21 | 59.79 | 100 |

| 5 | If she burns the food? | 45.84 | 54.16 | 100 |

| Latent Construct | Aspects Asked about | Factor Loadings (EFA) | p Value (CFA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decision-making power | Decisions on big household purchases | 0.244 | |

| Decisions on own health care | 0.591 | 0.000 | |

| Decisions on going to public meetings | 0.635 | 0.000 | |

| Attitude towards physical violence | Physical violence if she neglects children | 0.825 | |

| Physical violence if she argues with her partner | 0.755 | 0.000 | |

| Physical violence if she burns food | 0.695 | 0.000 | |

| Physical violence if she goes out without telling her partner | 0.745 | 0.000 | |

| Physical violence if she refuses to have sex | 0.825 | 0.000 |

| Predictors in the Equation (X): | Dependent Variables | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude Towards Violence | Decision-Making Power | Use of Family Planning | |

| Endogenous variables | |||

| 1. Decision-making power | 0.101 * | ||

| 2.Attitude towards violence | 0.104 ** | ||

| Exogenous variables | |||

| Current age of the women | 0.089 * | 0.463 *** | |

| Having access to information | 0.192 *** | ||

| Having access to a health facility | 0.140 *** | ||

| Having awareness about contraceptives | −0.118 ** | 0.240 *** | |

| Husband being employed | 0.091 ** | ||

| Age of the husband | −0.338 ** | −0.126 * | |

| Being from middle and higher wealth class | −0.114 *** | ||

| Rural residence | −0.085 ** | ||

| Occupation/no job or farmer | |||

| Religion | |||

| If she ever faced any form of violence | −0.116 ** | ||

| If she or husband has no habit of alcohol consumption | 0.153 *** | ||

| Partner not having habit of chewing/drinking | 0.195 ** | 0.262 *** | |

| Has exposure to education | 0.200 *** | ||

| Source of income | 0.153 ** | ||

| Husband being literate | 0.223 ** | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muluneh, M.D.; Francis, L.; Ayele, M.; Abebe, S.; Makonnen, M.; Stulz, V. The Effect of Women’s Empowerment in the Utilisation of Family Planning in Western Ethiopia: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6550. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126550

Muluneh MD, Francis L, Ayele M, Abebe S, Makonnen M, Stulz V. The Effect of Women’s Empowerment in the Utilisation of Family Planning in Western Ethiopia: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(12):6550. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126550

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuluneh, Muluken Dessalegn, Lyn Francis, Mhiret Ayele, Sintayehu Abebe, Misrak Makonnen, and Virginia Stulz. 2021. "The Effect of Women’s Empowerment in the Utilisation of Family Planning in Western Ethiopia: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 12: 6550. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126550

APA StyleMuluneh, M. D., Francis, L., Ayele, M., Abebe, S., Makonnen, M., & Stulz, V. (2021). The Effect of Women’s Empowerment in the Utilisation of Family Planning in Western Ethiopia: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6550. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126550