Parental Beliefs and Actual Use of Corporal Punishment, School Violence and Bullying, and Depression in Early Adolescence

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.1.1. Outcomes of Parental Actual Use of Corporal Punishment

1.1.2. Outcomes of Parental Beliefs about Corporal Punishment

1.2. Indirect Pathway through Parental Actual Use of Corporal Punishment

1.3. Aims of the Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measurement

2.2.1. Parental Beliefs about Corporal Punishment

2.2.2. Actual Use of Physical Punishment

2.2.3. Student Victimization by Students

2.2.4. Student Perpetration against Students

2.2.5. Maltreatment by School Teachers

2.2.6. Depression

2.3. Plan of Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

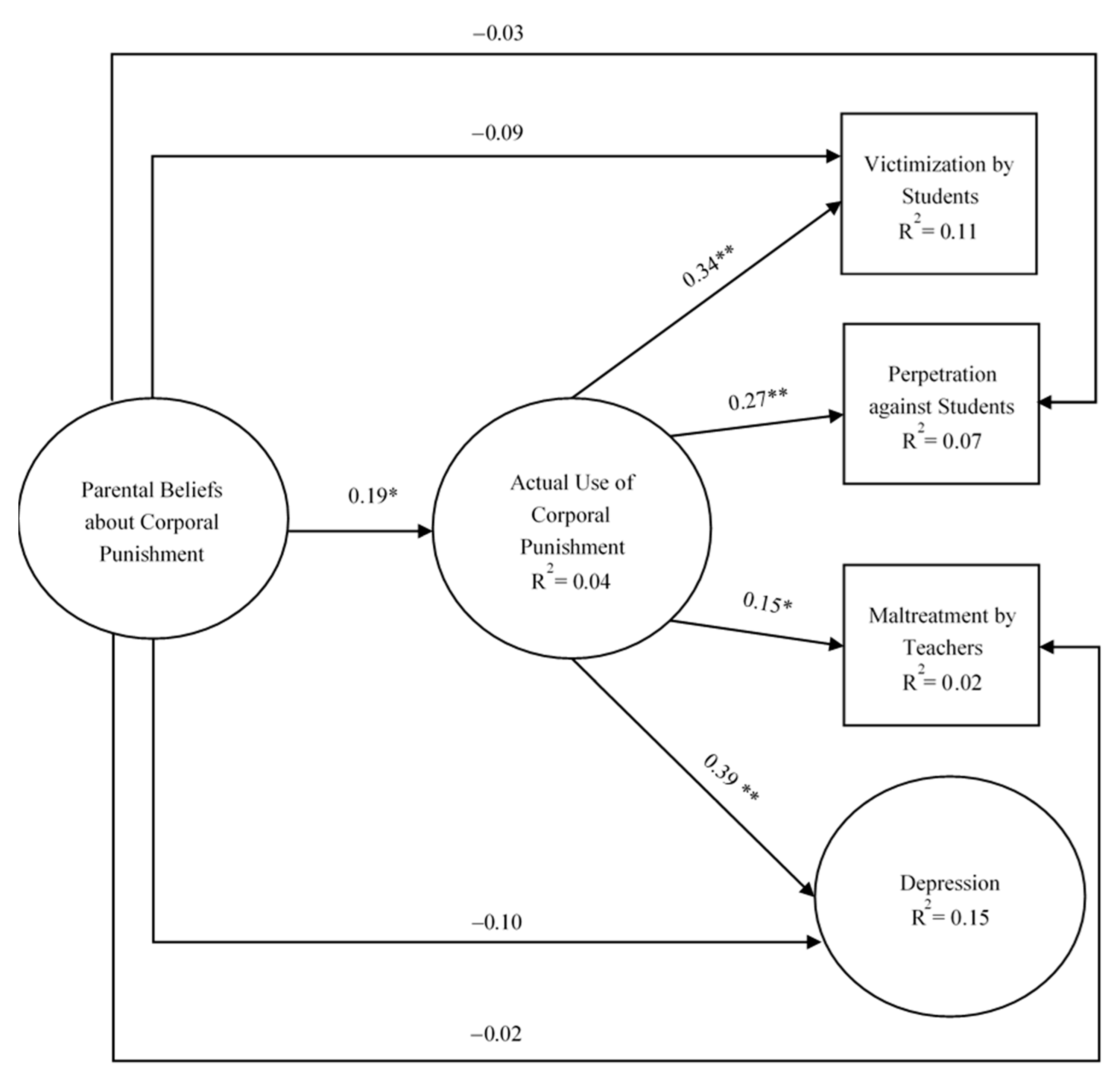

3.2. Overall Model

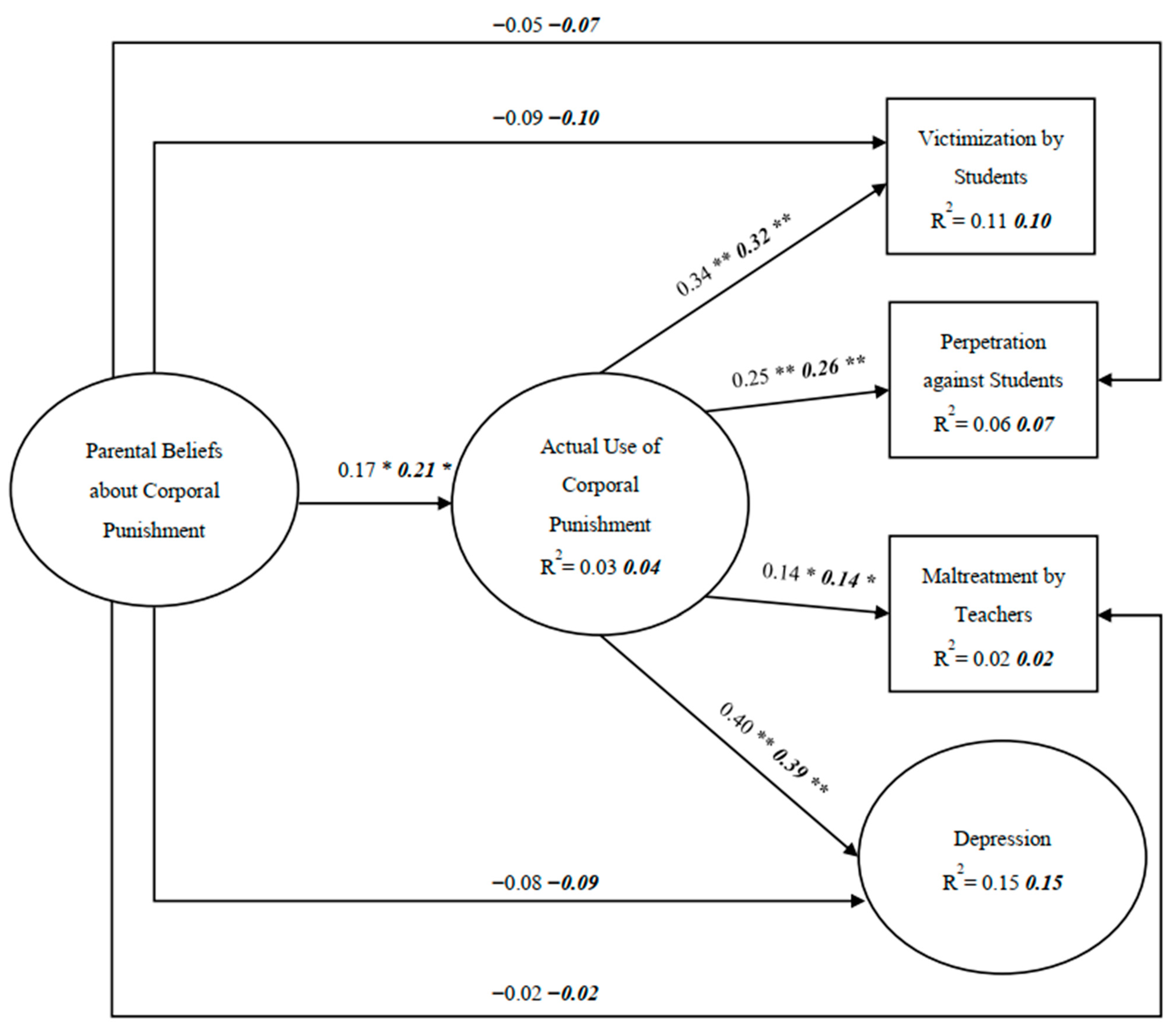

3.3. Gender Comparison

4. Discussion

4.1. Overall Model

4.2. Gender Differences

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Houbre, B.; Tarquinio, C.; Thuillier, I.; Hergott, E. Bullying among students and its consequences on health. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2006, 21, 183–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hymel, S.; Swearer, S.M. Four Decades of Research on School Bullying An Introduction. Am. Psychol. 2015, 70, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polanczyk, G.V.; Salum, G.A.; Sugaya, L.S.; Caye, A.; Rohde, L.A. Annual research review: A meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2015, 56, 345–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuwaja, H.M.A.; Karmaliani, R.; McFarlane, J.; Somani, R.; Gulzar, S.; Ali, T.S.; Premani, Z.S.; Chirwa, E.D.; Jewkes, R. The intersection of school corporal punishment and associated factors: Baseline results from a randomized controlled trial in Pakistan. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Adolescent Mental Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- UNESCO. School Violence and Bullying: Global Status Report; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.L.; Chen, W.J.; Lin, K.C.; Shen, L.J.; Gau, S.S. Prevalence of DSM-5 mental disorders in a nationally representative sample of children in Taiwan: Methodology and main findings. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2019, 29, e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.K.; Astor, R.A. The Perpetration of School Violence in Taiwan An Analysis of Gender, Grade Level and School Type. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2009, 30, 568–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.K.; Astor, R.A. School Violence in Taiwan: Examining How Western Risk Factors Predict School Violence in an Asian Culture. J. Interpers. Violence 2010, 25, 1388–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.K.; Chen, L.M. A Cross-National Examination of School Violence and Nonattendance Due to School Violence in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Mainland China: A Rasch Model Approach. J. Sch. Violence 2020, 19, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.K.; Wu, C.Y.; Chang, C.W.; Wei, H.S. Indirect effect of parental depression on school victimization through adolescent depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 263, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.K.; Wu, C.Y.; Wei, H.S. Personal, family, school, and community factors associated with student victimization by teachers in Taiwanese junior high schools: A multi-informant and multilevel analysis. Child Abus. Negl. 2020, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.K.; Wei, H.S. School violence, social support and psychological health among Taiwanese junior high school students. Child Abus. Negl. 2013, 37, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.K.; Wei, H.S. Student victimization by teachers in Taiwan: Prevalence and associations. Child Abus. Negl. 2011, 35, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.K.; Wei, H.S. The Impact of School Violence on Self-Esteem and Depression Among Taiwanese Junior High School Students. Soc. Indic. Res. 2011, 100, 479–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, C.A.; Finkelhor, D.; Clifford, C.; Ormrod, R.K.; Turner, H.A. Psychological distress as a risk factor for re-victimization in children. Child Abus. Negl. 2010, 34, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.P.; Xia, W.; Sun, C.H.; Zhang, H.Y.; Wu, L.J. Psychological distress and its correlates in Chinese adolescents. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2009, 43, 674–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.T.; Chan, K.L. Parental absence, child victimization, and psychological well-being in rural China. Child Abus. Negl. 2016, 59, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, C.J. Spanking, corporal punishment and negative long-term outcomes: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 33, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershoff, E.T. Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 128, 539–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Ortiz, O.; Romera, E.M.; Ortega-Ruiz, R. Parenting styles and bullying. The mediating role of parental psychological aggression and physical punishment. Child Abus. Negl. 2016, 51, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, R.L.; Wu, C.I.; Lin, K.H.; Gordon, L.; Conger, R.D. A cross-cultural examination of the link between corporal punishment and adolescent antisocial behavior. Criminology 2000, 38, 47–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aucoin, K.J.; Frick, P.J.; Bodin, S.D. Corporal punishment and child adjustment. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2006, 27, 527–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Bao, Z.; Nie, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, J. The association between corporal punishment and problem behaviors among Chinese adolescents: The indirect role of self-control and school engagement. Child Indic. Res. 2019, 12, 1465–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fass, M.N.; Khoury-Kassabri, M.; Koot, H.M. Associations between Arab Mothers’ Self-Efficacy and Parenting Attitudes and their children’s Externalizing and Internalizing Behaviors: Gender Differences and the Mediating Role of Corporal Punishment. Child Indic. Res. 2018, 11, 1369–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkinos, C.M.; Panayiotou, G. Parental discipline practices and locus of control: Relationship to bullying and victimization experiences of elementary school students. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2007, 10, 281–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.A.; Shanahan, L.; Deng, M.; Haskett, M.E.; Cox, M.J. Independent and Interactive Contributions of Parenting Behaviors and Beliefs in the Prediction of Early Childhood Behavior Problems. Parenting 2010, 10, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, M.H.; Putnick, D.L.; Suwalsky, J.T.D. Parenting cognitions --> parenting practices --> child adjustment? The standard model. Dev. Psychopathol. 2018, 30, 399–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benbenishty, R.; Astor, R.A.; Astor, R. School Violence in Context: Culture, Neighborhood, Family, School, and Gender; Oxford University Press on Demand: Kettering, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.-K.; Wu, C.; Wang, L.-C. Longitudinal Associations Between School Engagement and Bullying Victimization in School and Cyberspace in Hong Kong: Latent Variables and an Autoregressive Cross-Lagged Panel Study. Sch. Ment. Health 2021, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ouytsel, J.; Lu, Y.; Ponnet, K.; Walrave, M.; Temple, J.R. Longitudinal associations between sexting, cyberbullying, and bullying among adolescents: Cross-lagged panel analysis. J. Adolesc. 2019, 73, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottfredson, M.R.; Hirschi, T. A general theory of adolescent problem behavior: Problems and prespects. In Adolescent Problem Behaviors: Issues and Research; Ketterlinus, R.D., Lamb, M.E., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1994; pp. 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi, T. Causes of Delinquency; Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fearon, R.P.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; van Ijzendoorn, M.H.; Lapsley, A.M.; Roisman, G.I. The significance of insecure attachment and disorganization in the development of children’s externalizing behavior: A meta-analytic study. Child Dev. 2010, 81, 435–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeve, M.; Stams, G.J.; van der Put, C.E.; Dubas, J.S.; van der Laan, P.H.; Gerris, J.R. A meta-analysis of attachment to parents and delinquency. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2012, 40, 771–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wang, M.; Wang, T.; Wang, Z. Harsh Parental Discipline, Parent-Child Attachment, and Peer Attachment in Late Childhood and Early Adolescence. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2021, 30, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dussich, J.P.; Maekoya, C. Physical child harm and bullying-related behaviors: A comparative study in Japan, South Africa, and the United States. Int. J. Offender Comp. Criminol. 2007, 51, 495–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.Z.; Simons, L.G.; Simons, R.L. The effect of corporal punishment and verbal abuse on delinquency: Mediating mechanisms. J. Youth Adolesc. 2012, 41, 1095–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujikawa, S.; Ando, S.; Nishida, A.; Usami, S.; Koike, S.; Yamasaki, S.; Morimoto, Y.; Toriyama, R.; Kanata, S.; Sugimoto, N.; et al. Disciplinary slapping is associated with bullying involvement regardless of warm parenting in early adolescence. J. Adolesc. 2018, 68, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, S.Z.; Gibson, C.L. Corporal punishment’s influence on children’s aggressive and delinquent behavior. Crim. Justice Behav. 2011, 38, 818–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, H.L.; Allen, J.P.; McElhaney, K.B.; Antonishak, J.; Moore, C.M.; Kelly, H.O.; Davis, S.M. Use of harsh physical discipline and developmental outcomes in adolescence. Dev. Psychopathol. 2007, 19, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afifi, T.O.; Ford, D.; Gershoff, E.T.; Merrick, M.; Grogan-Kaylor, A.; Ports, K.A.; MacMillan, H.L.; Holden, G.W.; Taylor, C.A.; Lee, S.J. Spanking and adult mental health impairment: The case for the designation of spanking as an adverse childhood experience. Child Abus. Negl. 2017, 71, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulvaney, M.K.; Mebert, C.J. Stress Appraisal and Attitudes Towards Corporal Punishment as Intervening Processes Between Corporal Punishment and Subsequent Mental Health. J. Fam. Violence 2010, 25, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller-Perrin, C.L.; Perrin, R.D.; Kocur, J.L. Parental physical and psychological aggression: Psychological symptoms in young adults. Child Abus. Negl. 2009, 33, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, H.A.; Finkelhor, D. Corporal punishment as a stressor among youth. J. Marriage Fam. 1996, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, X.; Wang, M. Sex differences in the reciprocal relationships between mild and severe corporal punishment and children’s internalizing problem behavior in a Chinese sample. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2013, 34, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eamon, M.K. Antecedents and socioemotional consequences of physical punishment on children in two-parent families. Child Abus. Negl. 2001, 25, 787–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez, M.; Durtschi, J.; Neppl, T.K.; Stith, S.M. Corporal punishment and externalizing behaviors in toddlers: The moderating role of positive and harsh parenting. J. Fam. Psychol. 2016, 30, 887–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngee Sim, T.; Ping Ong, L. Parent physical punishment and child aggression in a Singapore Chinese preschool sample. J. Marriage Fam. 2005, 67, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, P.T.; Harold, G.T.; Goeke-Morey, M.C.; Cummings, E.M.; Shelton, K.; Rasi, J.A.; Jenkins, J.M. Child emotional security and interparental conflict. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 2002, 67, 135. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, J.P. Breaking the links in intergenerational violence: An emotional regulation perspective. Fam. Process 2013, 52, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coley, R.L.; Kull, M.A.; Carrano, J. Parental endorsement of spanking and children’s internalizing and externalizing problems in African American and Hispanic families. J. Fam. Psychol. 2014, 28, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLoyd, V.C.; Kaplan, R.; Hardaway, C.R.; Wood, D. Does endorsement of physical discipline matter? Assessing moderating influences on the maternal and child psychological correlates of physical discipline in African American families. J. Fam. Psychol. 2007, 21, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskey, B.J.; Cartwright-Hatton, S. Parental discipline behaviours and beliefs about their child: Associations with child internalizing and mediation relationships. Child Care Health Dev. 2009, 35, 717–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulauf, C.A.; Sokolovsky, A.W.; Grabell, A.S.; Olson, S.L. Early risk pathways to physical versus relational peer aggression: The interplay of externalizing behavior and corporal punishment varies by child sex. Aggress. Behav. 2018, 44, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, X.; Wang, M. Gender Differences in the Moderating Effects of Parental Warmth and Hostility on the Association between Corporal Punishment and Child Externalizing Behaviors in China. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2016, 26, 928–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-K. Cyber victimisation, social support, and psychological distress among junior high school students in Taiwan and Mainland China. Asia Pac. J. Soc. Work 2020, 30, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.K.; Chen, L.M. Cyberbullying among adolescents in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Mainland China: A cross-national study in Chinese societies. Asia Pac. J. Soc. Work 2020, 30, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.S.; Chen, J.K. Filicide-suicide ideation among Taiwanese parents with school-aged children: Prevalence and associated factors. Child Abus. Negl. 2014, 38, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, H.-S.; Chen, J.-K. The relationships between family financial stress, mental health problems, child rearing practice, and school involvement among Taiwanese parents with school-aged children. J. Child Fam Stud. 2014, 23, 1145–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlong, M.J.; Greif, J.L.; Bates, M.P.; Whipple, A.D.; Jimenez, T.C.; Morrison, R. Development of the California school climate and safety survey-short form. Psychol. Sch. 2005, 42, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-W.; Yuan, R.; Chen, J.-K. Social support and depression among Chinese adolescents: The mediating roles of self-esteem and self-efficacy. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 88, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-K.; Hung, F.N. Sexual Orientation Victimization and Depression among Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Youths in Hong Kong: The Mediating Role of Social Support. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 2020, 679–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbuckle, J.L. Amos 25.0 User’s Guide; IBM SPSS: Chicago, IL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M.; Bonett, D.G. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K.A. A new incremental fit index for general structural equation models. Sociol. Methods Res. 1989, 17, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekmekci, H.; Malda, M.; Yagmur, S.; van IJzendoorn, M.H.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; Mesman, J. The Discrepancy Between Sensitivity Beliefs and Sensitive Parenting Behaviors of Ethnic Majority and Ethnic Minority Mothers. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 2016, 48, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, M.H. Form and function: Implications for studies of culture and human development. Cult. Psychol. 1995, 1, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children. Corporal Punishment of Children in Taiwan; Global Partnership to End Violence Against Children: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff, E.T.; Lee, S.J.; Durrant, J.E. Promising intervention strategies to reduce parents’ use of physical punishment. Child Abus. Negl. 2017, 71, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durrant, J.E.; Plateau, D.P.; Ateah, C.; Stewart-Tufescu, A.; Jones, A.; Ly, G.; Barker, L.; Holden, G.W.; Kearley, C.; MacAulay, J. Preventing punitive violence: Preliminary data on the Positive Discipline in Everyday Parenting (PDEP) program. Can. J. Community Ment. Health 2014, 33, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrant, J.E.; Stewart-Tufescu, A.; Ateah, C.; Holden, G.W.; Ahmed, R.; Jones, A.; Ly, G.; Plateau, D.P.; Mori, I. Addressing punitive violence against children in Australia, Japan and the Philippines. J. Pac. Rim Psychol. 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, M.; Burkhart, K.; Cromly, A. Supporting positive parenting in community health centers: The ACT Raising Safe Kids Program. J. Community Psychol. 2013, 41, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.A.; Hamvas, L.; Rice, J.; Newman, D.L.; DeJong, W. Perceived social norms, expectations, and attitudes toward corporal punishment among an urban community sample of parents. J. Urban Health 2011, 88, 254–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Overall | Sex Groups | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | ||

| Parental beliefs about corporal punishment a | 6.17 | 6.32 | 6.03 |

| (1.81) | (1.74) | (1.87) | |

| Parental actual use of corporal punishment b | 3.65 | 4.37 | 3.03 |

| (3.99) | (4.22) | (3.68) | |

| Victimization by students b | 1.29 | 1.34 | 1.25 |

| (1.38) | (1.40) | (1.36) | |

| Perpetration against students b | 0.79 | 0.90 | 0.68 |

| (1.08) | (1.17) | (0.98) | |

| Maltreatment by teachers b | 0.21 | 0.24 | 0.18 |

| (0.58) | (0.60) | (0.56) | |

| Depression c | 5.60 | 5.60 | 5.59 |

| (2.70) | (2.78) | (2.64) | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Beliefs about corporal punishment | -- | 0.16 ** | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.02 |

| 2. Actual use of corporal punishment | -- | 0.27 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.14 ** | 0.34 ** | |

| 3. Victimization by students | -- | 0.54 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.29 ** | ||

| 4. Perpetration against students | -- | 0.34 ** | 0.24 ** | |||

| 5. Maltreatment by teachers | -- | 0.12 * | ||||

| 6. Depression | -- |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, J.-K.; Pan, Z.; Wang, L.-C. Parental Beliefs and Actual Use of Corporal Punishment, School Violence and Bullying, and Depression in Early Adolescence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6270. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126270

Chen J-K, Pan Z, Wang L-C. Parental Beliefs and Actual Use of Corporal Punishment, School Violence and Bullying, and Depression in Early Adolescence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(12):6270. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126270

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Ji-Kang, Zixin Pan, and Li-Chih Wang. 2021. "Parental Beliefs and Actual Use of Corporal Punishment, School Violence and Bullying, and Depression in Early Adolescence" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 12: 6270. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126270

APA StyleChen, J.-K., Pan, Z., & Wang, L.-C. (2021). Parental Beliefs and Actual Use of Corporal Punishment, School Violence and Bullying, and Depression in Early Adolescence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6270. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126270