1. Introduction

A growing proportion of the population is benefitting from the social, occupational, and academic opportunities offered by higher education. In recent years, there has been a three percent increase in higher education enrolments across both undergraduate and post-graduate university students, with larger numbers of ethnic minority students and students registering with a disability [

1]. For many, higher education is a major transition met with increasing social, academic, and financial demands [

2,

3]. Rates of mental health difficulties amongst university students are noteworthy. A global survey of 13,984 students found 35% reported at least one DSM-IV mental disorder [

4]. Rates of self-reported depression and anxiety in the United Kingdom are greater than the age-matched United Kingdom general population [

5]. A growing body of research suggests that mental health difficulties worsen throughout the degree programme [

6,

7,

8]. Whilst an increase in symptoms may not be caused by higher education itself, it is frequently suggested that the daily stressors associated with university life are a significant contributing factor [

7]. Post-graduate students are burdened with additional daily stressors, including difficulties in the supervisory relationship and isolation [

9].

The negative impact of having a mental health problem during university is broad, impacting the quality of life. Specifically, the presence of depressive symptoms in university students has been associated with role limitations due to physical health problems; while anxiety symptoms have been related to bodily pain; and both depressive and anxiety symptoms have been associated with reductions in general health, energy/fatigue, social functioning, as well as psychological distress, and lower psychological wellbeing [

10]. It has also been observed that mental health problems during university affect academic performance [

11] and the likelihood of dropping out [

12]. Recently, UK Universities called for universities to transform institutions into “mentally healthy universities” that place the mental health and wellbeing of staff and students as foundational for all aspects of the university system [

13]. The strategic framework developed by UK Universities outlines university-wide systematic changes which can be made across different domains (e.g., learning, support, etc.). For example, under the ‘learn’ domain, universities must make sure assessments “stretch and test” learning without imposing unnecessary stress. The ‘support’ domain focusses on implementing, in consultation with staff and students, safe and effective mental health interventions that are regularly audited for safety, quality and effectiveness [

13]. Whilst cognitive, behavioural and mindfulness-based interventions have been found to effectively reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression in university students [

14], the implementation of such interventions should be conducted in collaboration with university students to ensure that there is a demand for such programmes and that interventions are acceptable and accessible for all [

13].

Over the last decades, there has been a growing interest both nationally and internationally in mindfulness-based programmes (MBPs) in higher education institutions [

15]. Mindfulness is a natural, trainable capacity, which encourages people to approach experiences with attitudes of curiosity and care, and in ways that support overall wellbeing, and general functioning [

16,

17]. By training ‘mindful awareness’, MBPs aim to promote a conscious shift away from automatic, habitual responses that may increase distress towards greater self-regulation [

17]. As well as cultivating mindfulness skills, the psycho-educational content within MBPs can be tailored to the target population whilst promoting an understanding of psychological processes at the core of distress and wellbeing [

18]. A meta-analytic review of MBPs implemented in universities found overall improvements in depression, anxiety and wellbeing for students post-intervention, with lasting effects (>3 months) on distress [

19]. MBPs should be further tested for their appropriateness with a student population, ensuring people across the spectrum of wellbeing can make use of them and at a level of intensity that balances accessibility with potency [

20].

One example of an MBP is the “Mindfulness: Finding Peace in a Frantic World” course (M-FP) [

21], which was adapted from Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) [

22] to be an accessible universal MBP. The course is developed for a non-clinical population and participants learn skills they can use in their daily lives to break the cycle of anxiety, stress, and exhaustion, as well as promote mental health and wellbeing [

21]. M-FP themes include psycho-education, waking up from autopilot, how to respond to negative thoughts and difficult feelings, and self-care. Delivered in a university context, M-FP aims to support students to develop sustained awareness of the different aspects of daily living. Students are then encouraged to apply mindfulness skills to manage emotions, as well as academic and social pressures that may occur in day-to-day university life.

A self-guided version of the M-FP course in a university sample had positive effects on depression, anxiety, stress, satisfaction with life, mindfulness and self-compassion, with good acceptability [

23]. A pragmatic randomised control trial using the instructor-led version of the M-FP course for university students alongside ‘mental health support as usual’ evidenced significant improvements in mental health difficulties in comparison to a control group [

24].

Students also report both direct and indirect improvements in study skills and behaviour, including greater analytical thinking and memory capacity, increased enjoyment of studying, and reduced procrastination [

25] following the M-FP course. Students reporting higher levels of mindfulness engage more with autonomous academic goals that are intrinsically motivated than students with lower levels of mindfulness [

26], which is a consistent predictor of academic achievement across different educational contexts [

27]. These findings are particularly relevant considering the disproportionate number of students with poor mental health who drop out of university or perform less well academically compared to those without mental health problems [

11,

12]. By providing students with internal resources to support wellbeing, mindfulness programmes could alleviate some of the disadvantages related to studying with poor mental health whilst potentially promoting positive academic behaviours. Trait mindfulness and behaving in accordance with intrinsic values are also related to greater wellbeing [

28]. This is in line with Self-determination theory, which suggests that the relationship between mindfulness, intrinsic motivation and wellbeing is driven by greater awareness of self, leading to the choice of behaviours that are consistent with individual interests, values, and desires. It follows that awareness, cultivated through MBPs, may improve academic outcomes. Exploring the effects of the MF-P on students’ motivations towards academic goals is an aim of the current study.

Whilst the effects of MBPs on mental health and wellbeing are widely researched [

29,

30], the mechanisms through which these improvements are facilitated remain unclear. There is growing evidence to suggest that both mindfulness and self-compassion may be important mechanisms of change [

31,

32]. For example, in a study of an instructor-led M-FP tailored for secondary school teachers, there was reduced stress and increased rates of wellbeing, mindfulness and self-compassion [

33]. Additionally, mindfulness and self-compassion have been shown to mediate improvements in wellbeing [

34], stress, burnout and mental health [

35].

The relationship between mindfulness and self-compassion is complex. Initially, it was conceptualised as a bidirectional relationship with each enhancing the other [

36], but emerging research suggests that mindfulness and self-compassion improve mental health and wellbeing independently [

37]. The delivery of the MBP may also impact these mechanisms for change, with the instructor-led delivery of the M-FP program indirectly improving wellbeing, mental health and burnout in secondary teachers by significantly enhancing mindfulness and self-compassion compared with the self-taught M-FP program [

20]. Such mechanisms are also yet to be tested in a university student population.

Resilience is another key mechanism of change in MBPs [

38]. Resilience refers to positive adaptation in the face of stress or trauma [

39], a skill which is of particular importance to university students, who are faced with a number of novel challenging experiences (e.g., increased academic and financial demands). Drawing upon clinical models depicting mechanisms of change, the cultivation of mindfulness skills is thought to enhance self-regulation skills, promoting the psychological resilience that supports mental health and wellbeing [

40]. This is supported by cross-sectional and experimental research, revealing a partially mediating serial relationship between mindfulness, resilience and subjective wellbeing in community, and university samples [

38,

41]. In a recent cross-sectional study of general population participants, significant direct effects of mindfulness, self-compassion and resilience on anxiety and depression symptoms were observed, and also indirect effects of mindfulness and self-compassion through resilience on depression symptoms were found [

42].

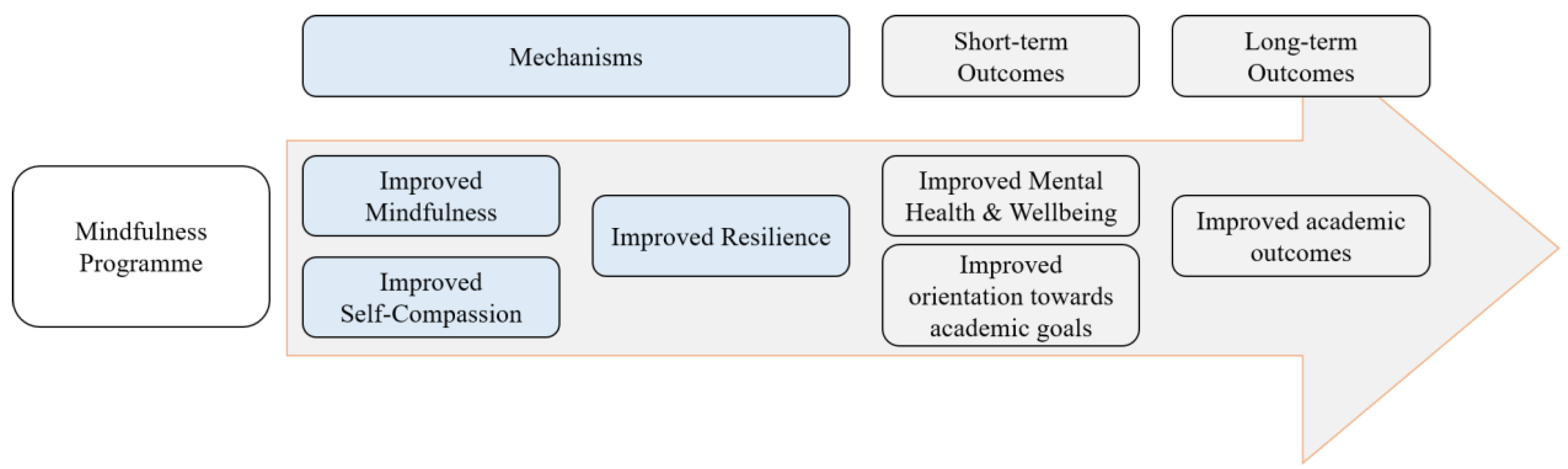

An improved understanding of the mechanisms of change for MBPs would enable further refinement of these programmes, thereby optimising individual outcomes. Mindfulness, self-compassion, and resilience are likely to be important mechanisms in MBPs for improving wellbeing and mental health outcomes in students. Based on the literature presented,

Figure 1 shows a proposed model whereby there is a sequential relationship between mindfulness, self-compassion, resilience, mental health, and academic outcomes. Testing this model is beyond the analytic and methodological capacity of this paper but forms the theoretical basis of the analyses conducted.

Study Aims

The present study explores engagement with acceptability and effectiveness of the instructor-led M-FP course [

21] in improving mental health and wellbeing in university students. Second, the impact of the M-FP course on the students’ orientation and motivation towards their academic goals is also explored. Finally, three mechanisms of change were independently explored in relation to mental health and wellbeing: (1) mindfulness, (2) self-compassion, and (3) resilience.

4. Discussion

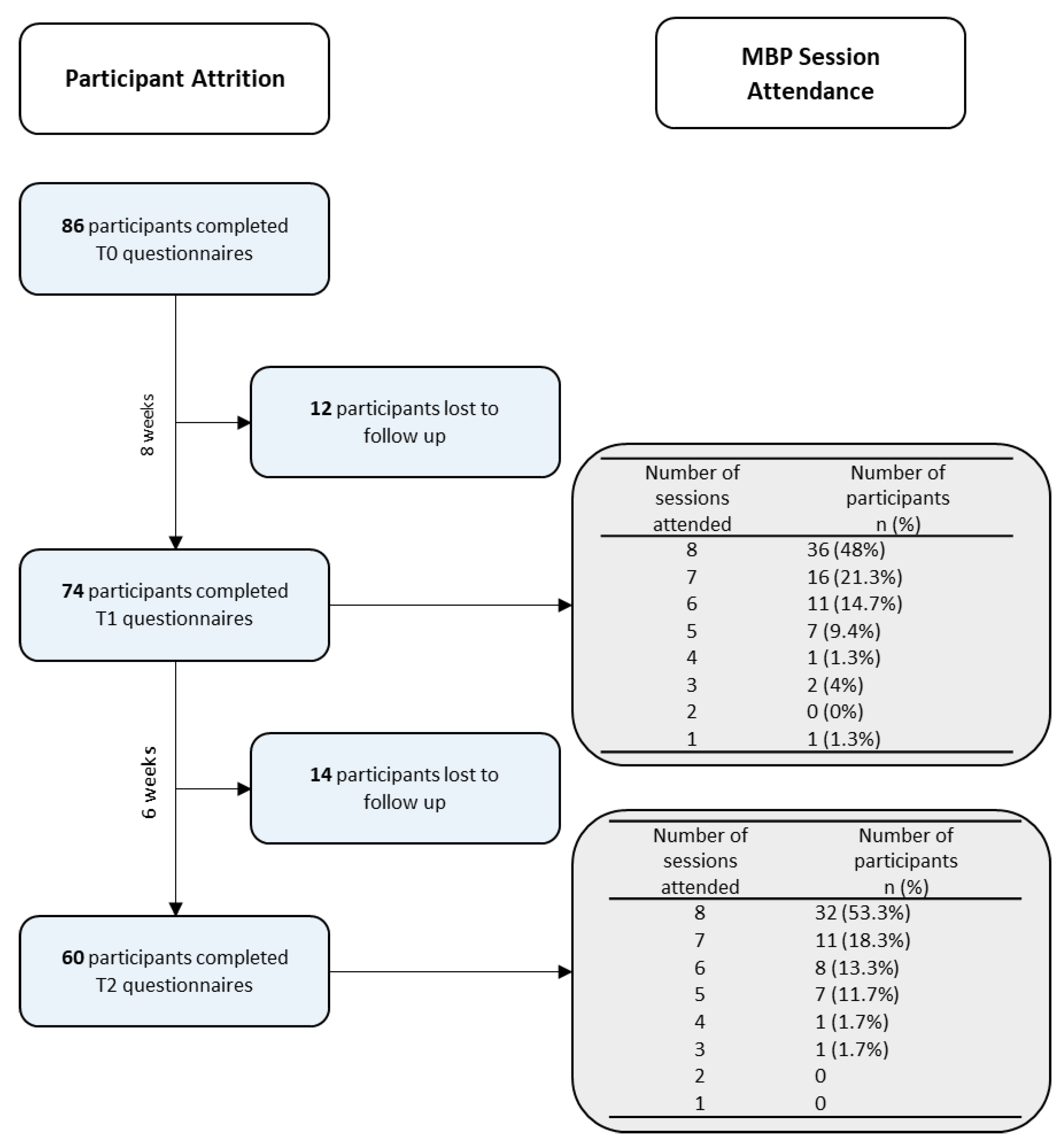

This study explored the acceptability and effectiveness of the ‘Mindfulness: Finding Peace in a Frantic World’ course [

21] in a university student population. Exploratory investigations were also conducted into changes in attitudes and motivation towards a self-selected academic goal. Preliminary explorations were conducted into the mediating role of mindfulness, self-compassion, and resilience for wellbeing and mental health (self-reported distress) independently. Results suggest that university students engaged with the M-FP course and reported high rates of acceptability. In addition, there were significant improvements in wellbeing and decreased mental health difficulties following the intervention and at 6-week follow-up, despite just under half of the sample attending all eight sessions. Improvements in wellbeing were significantly mediated by mindfulness, self-compassion, and resilience, whilst reductions in mental health problems were mediated by improvements in mindfulness and resilience, but not self-compassion. Further exploration revealed significant improvement in perceived “commitment” to, “likelihood” of achieving, and feeling more equipped with the “skills and resources” required to accomplish a self-selected academic goal at post-intervention and at 6-week follow-up. No improvements were revealed for intrinsic or extrinsic motivation towards academic goals.

The M-FP course had a moderate effect in improving wellbeing and decreasing mental health problems at post-intervention, with moderate-low effects at 6-week follow-up, which reflects similar findings from recent meta-analyses and systematic reviews exploring university student samples [

19,

69]. Consistent with previous research, improvements in wellbeing were associated with more time engaging in home practices [

70]. Engagement, by M-FP course attendance, was higher than alternative MBPs offered to university students [

23], and slightly lower in comparison to a secondary teacher sample [

20]. Engagement by home practice was lower than the recommended practice duration within the 8-week M-FP course (20 min per day) [

21], but it was within the previously reported total range of home practice for MBPs in university student samples [

23,

24]. Thus, universities might be implicated in improving student well-being by enhancing mindfulness home practice (e.g., making available tools that facilitate practice such as online platforms with tutorials, audios, videos, etc.). Participants perceived the course to be beneficial and useful, and many had intentions to continue using mindfulness in the future.

Ethnicity was a significant predictor of completion of the programme, and those who categorised themselves as being of white ethnicity attended significantly more sessions than other ethnic groups, although we recognise this is a small sample (

Table 1). This raises an important perspective on the inclusivity and accessibility of mindfulness interventions for individuals from minority ethnic backgrounds. Similar studies in the area [

23,

24] have not reported the relationship between ethnicity and attendance but have similar percentages of ethnic diversity in their participant groups. In a systematic review of Mindfulness and Meditation-Based Interventions (MMBI), only 24 out of 12,265 studies were identified as ‘diversity-focused’ [

71]. Research efforts, therefore, need to be made to ensure such courses are accessible, acceptable and effective to people across a range of ethnic backgrounds at the stage of both design and delivery.

The present student sample reported moderate (26%) rates of current mental health problems in line with recent student population estimates [

4,

10,

72]. Commonly, mindfulness practitioners advise against participation in MBPs if a potential participant is experiencing severe psychological distress, current depression, mania, or recent bereavement. In the present study, participants who reported experiencing current or past mental health problems reported significantly greater reductions in distress compared to those without current or past mental health problems. This reflects similar evidence from Galante et al. [

23], which found that baseline levels of distress moderated the benefit obtained from an MBP in a university student population. These findings could have important implications for the implementation and benefits of MBPs with vulnerable students and should be explored in further research.

There is preliminary evidence to suggest that MBPs implemented in a student population can impact academic outcomes and behaviour [

23,

25]. Whilst academic outcomes were not measured in the present study, we found an effect of time on students’ orientation towards their most important academic goal, suggesting the M-FP may have facilitated a more positive orientation towards academic goals. Intrinsic motivation is widely considered an important determinant for academic success [

27] and is associated with trait mindfulness [

73]. However, the present study did not find any significant changes in intrinsic and extrinsic motivation towards obtaining an academic goal following participation in the M-FP course. This finding is likely the result of ceiling effects, as much of the study sample reported very high levels of intrinsic motivation and very low levels of extrinsic motivation at baseline. This may arguably be characteristic of the present sample, comprising of students who have met the high entry requirements for studying at Oxford University [

74]. Future research would benefit from a more diverse sample representative of a broad university student population. However, this result could also be derived from the instrument that was used, which only included one single item to measure each academic goal domain. Nevertheless, these preliminary findings contribute to our understanding of the effectiveness of the M-FP course on improving students’ orientation towards their academic goals and may form the basis of future investigations.

In line with systematic reviews and meta-analyses exploring mechanisms of change in MBPs [

31,

32], mindfulness, resilience, and self-compassion were found to be significant mediators for pre-post-intervention changes in wellbeing. Furthermore, whilst improvements in distress were mediated by resilience and mindfulness, self-compassion was not found to significantly mediate improvements in distress in the present sample. This finding is consistent with previous findings from a study with a sample of secondary school teachers that found mindfulness, but not self-compassion, mediated changes between the frequency of mindfulness practice during an MBP and mental health outcomes [

20], suggesting that improvement in mental health symptoms and wellbeing may be driven by different pathways of change. Recent cross-sectional evidence from general population participants also found significant direct effects of mindfulness, self-compassion, and resilience on anxiety and depression symptoms, with indirect effects of mindfulness and self-compassion through resilience on depression symptoms [

42]. Thus, in order to optimise outcomes and delivery of MBPs, the disparity between mechanisms underpinning improvements in wellbeing and mental health symptoms, including distress, should be investigated further.

The findings are interpreted in the light of several limitations. Given the exploratory nature of our study, we did not control for multiple comparisons, possibly leading to false-positive findings. The study is characterised by a small sample size and large rates of attrition. Although statistical techniques were employed to address these characteristics, it may not have sufficient power to fully investigate all the questions proposed with the potential to lead to false-negative findings. Therefore, it is important that these findings are considered preliminary and that future research aims to formally test these observations in larger university student samples. The absence of a control condition means that it is unclear whether improvements in wellbeing, distress, mediators and the students’ orientation towards their academic goals can be attributed to their participation in the M-FP course or the passage of time. Students’ orientation towards their academic goals is a new line of enquiry. Thus, it is currently unknown how academic goal orientation (i.e., commitment to, likelihood of achieving, and having the skills and resources to achieve the academic goal) may fluctuate during the academic year. The present study did not explore the mechanisms through which the observed changes in academic goal orientation were facilitated to avoid over-testing. Future research may wish to explore these longitudinal changes by combining self-report measures of academic goal orientation with objective measures of academic achievement and study behaviour. As mentioned, the academic goal findings may also be derived from the instrument that was used, which only included one single item to measure each academic goal domain, and future research should improve the quality of the measures used in this regard. In addition, whilst the M-FP course was found to be particularly effective for students with mental health problems, these findings can also be explained by the observation of regression to the mean, as students reported high levels of mental health problems at study entry [

75]. Finally, opportunity sampling was employed, whereby students, who were already considering partaking in the M-FP course, were recruited. Hence, participants may present with characteristics (e.g., financial resources to afford course participation), which differ from the general student population at large, limiting the generalisability of the present findings. In this sense, we observed that ethnicity predicted completion of the programme, and that raises questions of inclusivity. For example, marginalized identities (rather racial, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, migrant, etc.) may play a role in the outcomes and would require special consideration, as findings may be differential based on students’ identity.