Adaptation Process of Korean Fathers within Multicultural Families in Korea

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Recruitment

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Study Validity and Researcher Preparation

2.6. Ethical Consideration

3. Results

3.1. Causal Conditions

Wouldn’t I also want to marry a Korean woman? I gave up because I had no money and I was getting older. So, I couldn’t marry a Korean woman, so I thought I had to pay the brokerage and marry a foreign woman from a developing country.(Participant 3)

When I was introduced by a marriage company, the biggest reason I was forced to get married was my age; I was over 50. When I turn 60, my child will be 10, but when the child becomes an adult, it seems that there will be a lot of pressure on the child, so I tried not to have a baby. But when I had a baby, I was forced to accept it.(Participant 8)

3.2. Central Phenomenon

I liked having a child, but my heart was torn. I am sorry that the bigger my child gets, the more responsibility I have to feed the child. I wanted to spend time with my child, but it was too busy and difficult because I had to make money. So, I couldn’t do that.(Participant 6)

Even though I wanted to quit because the work was so hard, I remembered when my child was just born, and I felt strong. As soon as the baby was born, the baby went straight into the newborn room, and the first time I saw the baby it was very small. The nurse told me to hug the baby, but my heart was so overwhelmed and I was tearing up, so I couldn’t hold him properly.(Participant 1)

3.3. Contextual Conditions

Too often, my wife doesn’t know anything about parenting. She simply skipped the regular schedule of immunizations for babies. Even if the hospital sent home an immunization mail, my wife couldn’t read the text. If my wife were a Korean woman, she could call around and ask. But my wife is a foreigner, so she doesn’t know.(Participant 5)

When my wife was pregnant, I was uncomfortable because I couldn’t understand what was wrong. We live on an island, so there are no hospitals. I asked my wife with gestures and talked. At first, I thought I couldn’t even do this anymore.(Participant 2)

When the baby was born and less than one year old, it was sick from a cold. But my wife applied tiger medicine to the baby’s head over the pores. I fought with her a lot at that time. She said that in her country they do that. My wife also applied the medicine to the baby’s belly. These days, tiger medicine is not used in Korea. But still, in my wife’s country, they apply it on the head of a 5- or 6-month-old baby and also on the belly.(Participant 4)

I said that my home situation is difficult economically, so I have to save. But my wife said she didn’t save money in her country, so she didn’t understand. When I think about it, it seems that in my wife’s country, which is a developing country, she was too poor to be able to save.(Participant 4)

The bigger the baby gets, the more I am worried about taking care of them. If I buy clothes for my baby, I still have to have clothes in the future, and though I want to dress well with pretty and nice clothes, I won’t have the money. As the baby grows, it will continue to cost a lot of money. But I haven’t saved any money. When I think about it, my heart is upset. Sometimes it’s comfortable not to think about it, so I just live like that.(Participant 2)

Anyway, I can’t afford it since I earn the money alone. Because I make money driving a taxi, there is no money to be saved, and I have to spend all that I make.(Participant 6)

I brought my wife’s mother from abroad to Korea, hoping that she would take good care of the baby. But my wife’s mother was sick and my money was spent for hospital bills.(Participant 11)

Since I am marrying a foreigner rather than a Korean, the biggest issue I think is that my child looks like a foreign child. As children grow older, their skin color and appearance is slightly different from normal [ethnically, homogenously Korean] children. So, as they grow older, I am worried that they will be alienated from their peers.(Participant 5)

I know my friends hate talking about my marriage to a foreign wife. So, they don’t directly express that my child is different, but they say this indirectly. “Your baby seems like a foreigner.” I’m upset by those words. So, I don’t meet more friends.(Participant 6)

One of the reasons I hesitated to marry internationally is because of how others look at it. I feel like people point at me, saying, “He bought a wife with money,” and look at me badly. When I went to a restaurant with my wife and she spoke to her mother in a foreign language, it seemed like everyone was looking at me. Multiculturalism itself is a stranger here.(Participant 10)

Since we live on the island, there is no hospital that we can use quickly even if our [my] wife and child are sick. There are no health clinics on the island where we live. People around me tell me to go to a pediatric hospital because they are careful about babies, but there is no hospital. It’s difficult because I have to go to the hospital with my wife and child. I have to go to work. My wife doesn’t speak [Korean] well, so I can’t tell her to go alone.(Participant 4)

I want to receive education about parenting together for my child on the weekend, but the educational institution is closed on the weekends. I don’t want to do that every day, but once a month, I wish I could use the weekend for education. However, since all education is provided during the day on weekdays, and I have to go to work, this is not possible. This is a problem.(Participant 11)

My wife is alone and is taking care of the baby, so I hope someone can come and help me if something goes wrong. Of course, it would be hard to be with my wife who doesn’t speak the language, but I wish I had someone who could help me when my baby is sick or needs help from time to time, not every day. But who can get to the island?(Participant 1)

3.4. Intervention Conditions

In the first few months after the baby was born, I couldn’t hold my baby because it felt like a threat to him. It’s not that I hate babies. I was afraid because I didn’t know how to hold the baby and had never done it before.(Participant 8)

After the baby was born, I kept talking to the baby in Korean and my wife did it in Vietnamese. I was worried that it would cause confusion in my baby’s language development.(Participant 2)

My child’s language development was a little late. Still, the child said “Dad” and “Mom.” About 30 months after birth, our child was about to start talking, but my wife went to Cambodia with him. Since then, the child has been confused and he is still unable to speak. I was so worried that I went to the speech therapy center. The speech therapist consulted with my child for 30 minutes and told me to pay 100,000 won. Due to the burden of the cost, I gave up receiving such speech therapy. When I tried to ask for speech therapy from the government or province, the government didn’t give it to us.(Participant 3)

My wife often fought with my mother. My wife is from a foreign country, so she doesn’t know Korean, but I think she had a different idea about raising a baby than my mother. I had a hard time every time these two quarreled. I understood my mother’s heart as well as my young wife’s heart.(Participant 5)

When the baby said “Dad” to me for the first time, I was thrilled. After that, the baby used the word “Dad” more than the word “Mom.” When I come home after work, the child runs to me. At that time, I am happy beyond words.(Participant 8)

My mother thought a lot of her. My mother thanked her for marrying her old, moneyless son. My mother often said to me, “Because your wife has come to a distant country and suffers, you should love her a lot.”(Participant 10)

The relationship between me and my family has improved. All the families gathered on a holiday. At that time, I had my child, so there were many topics for stories. Relatives bought toys for my child, and they loved him. Because I also have a child, meeting with my family is much easier and better than when I had no child.(Participant 2)

The creation of a family has made a difference in me. In the past, I didn’t meet people very well. But now, I have met a family similar to ours to eat and talk with. I found a multicultural family similar to ours, and we understand and get more help from such families.(Participant 3)

3.5. Action/Interaction Strategies

I regretted choosing a marriage like this at first. But this is my choice. I felt sorry for my wife, because she was also struggling to meet me with no money.(Participant 5)

I am working hard to play the role of head of household. When I go to the sea to make money, I have to take a long boat. When I come home after working a long time, I work in the field again. I am living hard. There are two more members of my family who are looking to me, but I am happy to be a father and work for my child.(Participant 1)

This baby is my first child, so I try to spend a lot of time with it. But actually, I’m having a hard time. I can’t just leave the child care to my wife, so I try my best to be with her.(Participant 5)

After my child was born, I felt more responsible. I don’t have a lot of money, so I have to spend money within limits. I didn’t waste my money before I got married. However, I think my financial responsibilities have increased with the appearance of the baby and the family.(Participant 8)

I studied Cambodian language a lot on my cell phone. I can’t write in Cambodian language, but if I use a lot of words in Cambodian, I thought I could talk on the phone. So, we talk on the phone in Cambodian. I’m still studying Cambodian language.(Participant 5)

When she had to go to the hospital, I always took her with me. It’s hard to use transportation facilities in the countryside, so I always tried to go with her. It could be dangerous for a pregnant woman as she might fall while riding a bus alone. I thought it was dangerous for the child in that situation. I thought going to the hospital with my wife is the first priority because she can’t speak Korean well.(Participant 1)

3.6. Consequences

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Status of Foreigners Staying. Available online: https://www.index.go.kr/potal/main/EachDtlPageDetail.do?idx_cd=2756 (accessed on 4 May 2021).

- Ministry of Gender Equality and Family Announces the 4th Basic Plan for Healthy Families (2021–2025). Available online: https://www.korea.kr/news/visualNewsView.do?newsId=148886737 (accessed on 4 May 2021).

- 2018 Annual Report on Multicultural Families’ Statistics. Available online: http://www.mogef.go.kr/mp/pcd/mp_pcd_s001d.do?mid=plc503 (accessed on 4 May 2021).

- Bond, S. The essential role of the father: Fostering a father-inclusive practice approach with immigrant and refugee families. J. Fam. Soc. Work 2019, 22, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, L.; Low, J.; Siler, C.; Hackett, R.K. Understanding the contribution of a father’s warmth on his child’s social skills. Fathering 2013, 11, 90–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.J.; Lee, K.H. The fathering experiences of Korean father in multicultural family. J. Korea Open Assoc. Early Child. Educ. 2012, 17, 69–98. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.K.; Jo, H.S. Child-rearing practices of fathers in multicultural families. J. Korea Open Assoc. Early Child. Educ. 2015, 20, 345–381. [Google Scholar]

- Singley, D.B.; Edwards, L.M. Men’s perinatal mental health in the transition to fatherhood. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2015, 46, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfield, C.F.; Isacco, A.; Bartlo, W. Men’s health and fatherhood in the urban midwestern United states. Int. J. Men’s. Health 2010, 9, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzo, K.B. New father experiences with their own fathers and attitudes toward fathering. Fathering 2011, 9, 268–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.E.; Ahn, J.A. Effect of intervention programs for improving maternal adaptation in Korea: Systematic review. Korean J. Women Health 2013, 19, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.E.; Roh, E.H.; Park, S.M. Systematic review of quantitative research related to maternal adaptation among women immigrants by marriage in Korea. Korean J. Women Health 2015, 21, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.E.; Ahn, J.A.; Kim, T.; Roh, E.H. A qualitative review of immigrant women’s experiences of maternal adaptation in South Korea. Midwifery 2016, 39, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Huang, H. A review of parents’ education programs for multicultural families in Korea. J. Educ. Cult. 2015, 21, 287–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, K.; Chung, M. Grounded theory study on a parenting practices and type of the father with child. Korean J. Early Child. Educ. 2018, 38, 367–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.H. Analysis of trends in Korea research on father. Korean J. Play Ther. 2011, 14, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.H.; Choi, H.S. An analysis on the research trend of father’s child-rearing involvement. Korean J. Youth Stud. 2014, 21, 307–330. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.S.; Park, H.S. Moderating effects of stress-coping levels and social support on the relation between parenting stress of fathers in multicultural families and rejective parenting. J. Eco-Early Child. Educ. 2016, 15, 71–92. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.S.; Park, H.S. Effect of parenting stress of fathers in multicultural families on child’s peer competence and teacher-child relationship through rejective parenting. J. Early Child. Educ. 2017, 37, 759–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, T.H.; Kim, E.H. The moderating effects of stress-coping strategies and anger rumination: Parental stress and Hwa-Byung among fathers of multicultural families. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 40, 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A.L. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 1–130. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.; Guba, E. The Roots of fourth generation evaluation: Theoretical and methodological origins. In Evaluation Roots; Alkin, M.C., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 226–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, G.L.; Nordquist, V.M.; Billen, R.M.; Savoca, E.F. Father involvement and early intervention: Effects of empowerment and father role identity. Fam. Relat. 2015, 64, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikorska, M. From “absent father” to “involved father”: Changes in the model of fatherhood in Poland and role of mothers-“gatekeepers”. In Balancing Work and Family in a Changing Society, 1st ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parke, R.D. Fathers, families, and the future: A plethora of plausible predictions. Merrill-Palmer Q. 2004, 50, 456–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Je, M.; Son, H.M.; Kim, Y.H. Development and effect of a cultural competency promotion program for nurses in obstetrics-gynecology and pediatrics. Child Health Nurs. Res. 2015, 21, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Yeo, Y.H. Determining Factors of Parentification among the Multicultural Families’ Children. AJMAHS 2019, 9, 913–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Kim, M.J. Marriage migration and gender role attitudes of husbands in a receiving country: Comparing gender role attitudes of Korean husbands in transnational marriage with those of national marriage. KJCS 2020, 28, 273–327. [Google Scholar]

- Draper, J. ‘It was a real good show’: The ultrasound scan, fathers and the power of visual knowledge. Sociol. Health Illn. 2002, 24, 771–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquette, D. Theorizing the father-child relationship: Mechanisms and developmental outcomes. Hum. Dev. 2004, 47, 193–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, Z.; Behpajooh, A.; Ghobari-Bonab, B. The effectiveness of nonviolent communication program training on mother-child interaction in mothers of children with intellectual disability. J. Rehabil. 2019, 20, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. A review of the study on father involvement in child rearing. Asian Soc. Sci. 2019, 15, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Categories | (N = 11) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Age (in years) | 40–49 | 9 (81.8) | 48.09 ± 5.13 |

| 50–59 | 2 (18.2) | ||

| Age gap between participant and wife (in years) | 10–14 | 4 (36.4) | 17.55 ± 4.93 |

| 15–19 | 4 (36.4) | ||

| 20–25 | 3 (27.3) | ||

| Occupation | Day laborer | 3 (27.3) | |

| Public officer | 1 (9.1) | ||

| Driver | 5 (45.4) | ||

| Agriculture and fisheries | 2 (18.2) | ||

| Type of family | Nuclear family | 11 (100) | |

| Large family | 0 (0) | ||

| Residential district | Rural area | 4 (36.4) | |

| Urban area | 7 (63.6) | ||

| Wife’s nationality | Vietnamese | 5 (45.4) | |

| Cambodian | 4 (36.4) | ||

| Filipino | 2 (18.2) | ||

| Type of childbirth | Spontaneous delivery | 3 (27.3) | |

| Cesarean surgery | 8 (72.7) | ||

| Type of hospital for childbirth | Women’s hospital | 11 (100) | |

| Tertiary hospital | 0 (0) | ||

| Place of postnatal care | Home | 8 (73.7) | |

| Hospital + Home | 3 (27.3) | ||

| Prenatal education | Participated | 2 (18.2) | |

| Not participated | 9 (81.8) | ||

| Postpartum education | Participated | 4 (36.4) | |

| Not participated | 7 (63.6) | ||

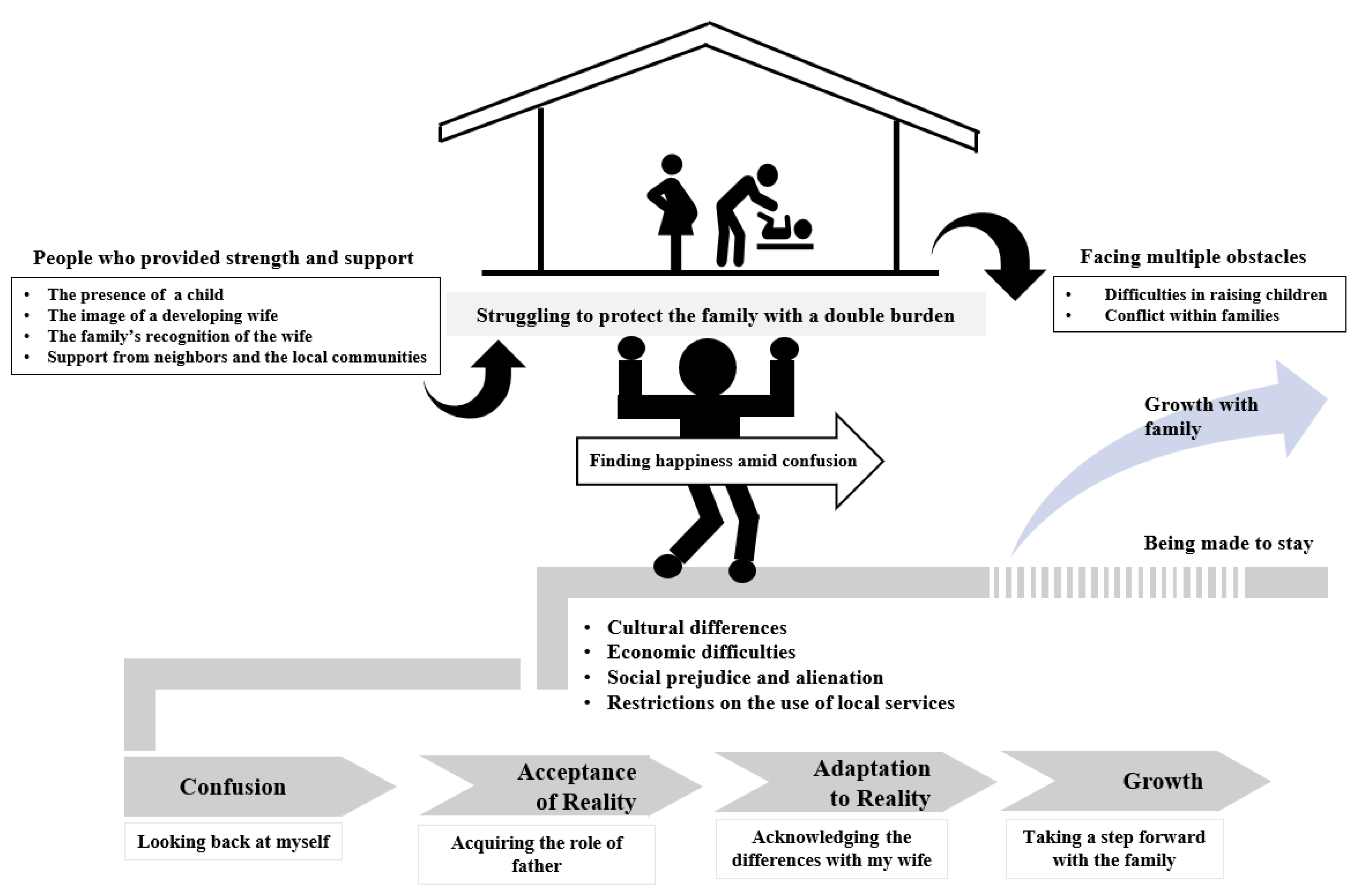

| Subcategories | Categories | Paradigm Element |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous suggestions from family and neighbors | Multicultural family reluctantly formed | Causal Conditions |

| Unwilling marriage | ||

| Being a father by compelling circumstances. | ||

| The confusion of being a father | Finding happiness amid confusion | Central phenomenon |

| The thrill of being a father | ||

| Different languages | Cultural differences | Contextual conditions |

| Differences in values | ||

| Differences in nurturing | ||

| Restrictions on economic activities due to aging | Economic difficulties | |

| The burden of increasing dependents | ||

| Spousal differences in financial views | ||

| Uncomfortable gazes from others at children’s exotic appearance | Social prejudice and alienation | |

| Negative perceptions of multicultural families | ||

| Medical services in islands with low accessibility | Restrictions on the use of local services | |

| Services of community institutions that are not easy to use | ||

| Difficulties in raising children | Facing multiple obstacles | Intervention conditions |

| Conflict within families | ||

| The presence of a child | People who provided strength and support | |

| The image of a developing wife | ||

| The family’s recognition of the wife | ||

| Support from the neighbors and the local communities | ||

| Looking back on myself | Accepting the differences and moving forward | Action/ Interaction strategies |

| Acquiring the role of father | ||

| Acknowledging the differences with the wife | ||

| Taking a step forward with the family | ||

| Personal maturity | Growth with family | Consequences |

| Win-win growth with children | ||

| Win-win growth with spouse | ||

| Crash against the wall of reality | Being made to stay | |

| Live inevitably |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, S.-Y.; Kim, S.; Cho Chung, H.-I. Adaptation Process of Korean Fathers within Multicultural Families in Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5935. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115935

Park S-Y, Kim S, Cho Chung H-I. Adaptation Process of Korean Fathers within Multicultural Families in Korea. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(11):5935. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115935

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, So-Yeon, Suhyun Kim, and Hyang-In Cho Chung. 2021. "Adaptation Process of Korean Fathers within Multicultural Families in Korea" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 11: 5935. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115935

APA StylePark, S.-Y., Kim, S., & Cho Chung, H.-I. (2021). Adaptation Process of Korean Fathers within Multicultural Families in Korea. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(11), 5935. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115935