Influence of Social Support and Subjective Well-Being on the Perceived Overall Health of the Elderly

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. Perceived Social Support

2.2.2. Satisfaction with Life

2.2.3. Self-Esteem

2.2.4. Perceived Overall Health

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

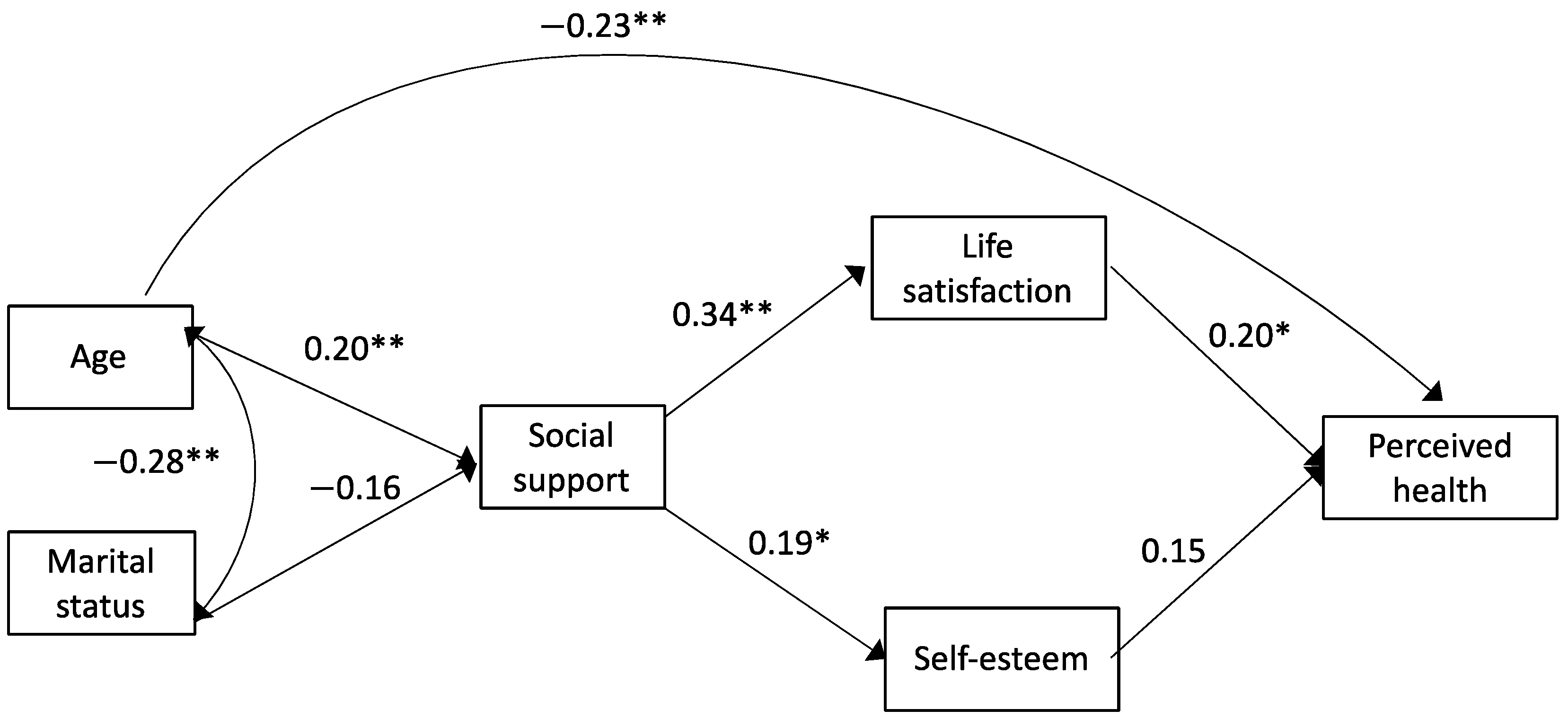

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abellán García, A.; Aceituno Nieto, P.; Pérez Díaz, J.; Ramiro Fariñas, D.; Ayala García, A.; Pujol Rodríguez, R. Un Perfil de las Personas Mayores en España, 2019. Indicadores Estadísticos Básicos; Instituto de Economía, Geografía y Demografía: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Rojo, G.; Chulián, A.; López Martínez, J.; Noriega, C.; Velasco, C.; Carretero, I. Buen y mal trato hacia las personas mayores: Teorías explicativas y factores asociados. Rev. Clín. Contemp. 2017, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadistica (INE). Avance de la Estadística del Padrón Continuo a 1 de enero de 2020; Instituto Nacional de Estadistica (INE): Madrid, Spain, 2019.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadistica (INE). Proyecciones de Población 2018; Instituto Nacional de Estadistica (INE): Madrid, Spain, 2018; pp. 1–20.

- Arias, C.J.; Iacub, R. ¿Por qué investigar aspectos positivos en la vejez? Contribuciones para un cambio de paradigma. Publ. UEPG Ciências Hum. Linguist. Let. Artes 2013, 21, 271. [Google Scholar]

- Petretto, D.R.; Pili, R.; Gaviano, L.; Matos López, C.; Zuddas, C. Envejecimiento activo y de éxito o saludable: Una breve historia de modelos conceptuales. Rev. Esp. Geriatr. Gerontol. 2016, 51, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramowska-Kmon, A.; Timoszuk, S. Family network, wellbeing and loneliness among odler adults in Poland. Studia Demogr. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motkal Abu-Rayya, H. Depression And Social Involvement Among Elders. Internet J. Health 2006, 5, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Farré, A. Autopercepción del proceso de envejecimiento en la mujer entre 50 y 60 años. Anu. Psicol. UB J. Psychol. 1991, 50, 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Charles, S.T.; Carstensen, L.L. Emotion Regulation and Aging. In Handbook of Emotion Regulation; Gross, J.J., Ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 307–327. [Google Scholar]

- Granzin, K.L.; Haggerd, L.M. An Integrative Explanation for Quality of Life: Development and Test of a Structural Model. In Advances in Quality of Life Theory and Research; Diener, E., Rahtz, D.R., Eds.; Kluwer Academic: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2000; pp. 31–63. [Google Scholar]

- Cuervo-Arango, M.A. La calidad de vida. Juicios de satisfacción y felicidad como indicadores actitudinales de bienestar. Rev. Psicol. Soc. 1993, 8, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Sierra, S.M.; Rivera-Porras, D.; Garcia-Echeverri, M.; González, R. Envejecimiento e intervenciones terapéuticas desde la perspectiva psicológica a adultos mayores: Una revisión descriptiva. Arch. Venez. Farmacol. Ter. 2020, 39, 903–911. [Google Scholar]

- Herdman, M.; Badia, X.; Berra, S. EuroQol-5D: A simple alternative for measuring health-related quality of life in primary care. Aten. Primaria 2001, 28, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mella, R.; González, L.; D’Appolonio, J.; Maldonado, I.; Fuenzalida, A.; Díaz, A. Factores Asociados al Bienestar Subjetivo en el Adulto Mayor. Psykhe 2004, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamarrón, M.D. El bienestar subjetivo en la vejez. Inf. Portal Mayores 2006, 52, 119–127. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E. Subjective Well-Being. Psychol. Bull. 1984, 95, 542–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E.; Suh, E.M.; Lucas, R.E.; Smith, H.L. Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, W.I.T.; Galaz, M.M.F. Factores predictores del bienestar subjetivo en adultos mayores. Rev. Psicol. 2018, 36, 9–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Veni, R.K.; Merlene, A. Gender differences in self-esteem and quality of life among the elderly. Indian J. Health Wellbeing 2017, 8, 885–887. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaev, B. Does higher education increase hedonic and eudaimonic happiness? J. Happiness Stud. 2018, 19, 483–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Martín, J.L.; Barra, E. Autoestima, apoyo social y satisfacción vital en adolescentes. Ter. Psicol. 2013, 31, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almagiá, E.B. Apoyo social, estrés y salud. Psicol. Salud 2004, 14, 237–243. [Google Scholar]

- Bozo, Ö.; Toksabay, N.E.; Kürüm, O. Activities of daily living, depression, and social support among elderly Turkish people. J. Psychol. 2009, 143, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, J.; Epperly, L.; Barnes, K. Gender, emotional support, and well-being among the rural elderly. Sex Roles 2001, 45, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, C.; Rodriguez, E. Loneliness and isolation, barriers and conditionings in the field of older people in Spain. Ehquidad Rev. Int. Políticas Bienestar Trab. Soc. 2019, 127–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doblas, J.L.; Conde, M.D. Viudedad, soledad y salud en la vejez. Rev. Esp. Geriatr. Gerontol. 2018, 53, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vivaldi, F.; Barra, E. Bienestar Psicológico, Apoyo Social Percibido y Percepción de Salud en Adultos Mayores. Ter. Psicol. 2012, 30, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa-Fernández, M.; Pérez-Padilla, J.; Nunes, C.; Menéndez, S. Bienestar psicológico en las personas mayores no dependientes y su relación con la autoestima y la autoeficacia. Cien. Saude Colet. 2019, 24, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Morales, A.; Miranda, J.M.; Pergola-Marconato, A.M.; Mansano-Schlosser, T.C.; Mendes, F.R.P.; Torres, G.D. Influencia de las actividades en la calidad de vida de los ancianos: Revisión sistemática. Cien. Saude Colet. 2019, 24, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazloomymahmoodabad, S.; Masoudy, G.; Fallahzadeh, H.; Jalili, Z. Education based on precede-proceed on quality of life in elderly. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2014, 6, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadhead, W.; Gehlbach, S.; Care, F.D.G.-M. The Duke–UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire: Measurement of social support in family medicine patients. Med. Care 1988, 26, 707–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuéllar-Flores, I.; Dresch, V. Validación del cuestionario de Apoyo Social Funcional Duke-UNK-11 en personas cuidadoras. Rev. Iberoam. Diagn. Eval. Psicol. 2012, 2, 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Moyano, N.C.; Martínez, M.; Muñoz, M.P. Propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de Satisfacción con la Vida de Diener. Rev. Argent. Clín. Psicol. 2013, 22, 161–168. [Google Scholar]

- Atienza Gonzalez, F.L.; Moreno Sigüenza, Y.; Balaguer Solá, I. Análisis de la Dimensionalidad de la Escala de Autoestima de Rosenberg en una Muestra de Adolescentes Valencianos. Rev. Psicol. 2000, 22, 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- De León Ricardi, C.A.; García Méndez, M. Escala de Rosenberg en población de adultos mayores. Cienc. Psicol. 2016, 10, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badia, X.; Roset, M.; Montserrat, S.; Herdman, M.; Segura, A. La versión española del EuroQol: Descripción y aplicaciones. Med. Clin. 1999, 112, 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Balestroni, G.; Bertolotti, G. EuroQol-5D (EQ-5D): An instrument for measuring quality of life. Monaldi Arch. Chest Dis. 2012, 78, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M.; Wu, E.J.C. EQS 6.1 for Windows; Multivariate Software: Encino, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacker, R.E. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sluzki, C.E. La Red Social: Frontera de la Práctica Sistémica; Editorial Gedisa, S.A.: Barcelona, España, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera Navarro, J.; Benito-León, J.; Pazzi Olazarán, K.A. La Depresión en la Vejez: Un Importante Problema de Salud en México. Am. Lat. Hoy 2015, 71, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Herrera Hernández, J.M.; Espósito Barranco, C.; Melián Medina, C.; Herrera Hernández, R.; Rodriguez Matos, M.I.; Mesa Espósito, M.N. La autoestima como predictor de la calidad de vida de los mayores. Portularia Rev. Trab. Soc. 2004, 4, 171–178. [Google Scholar]

- Abellán García, A.; Aceituno Nieto, P.; Pérez Díaz, J.; Ramiro Fariñas, D.; Ayala García, A.; Pujol Rodríguez, R. Factores asociados al bienestar subjetivo en el adulto mayor. Psykhe 2004, 1, 79–89. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Alba, R.; Manrique-Abril, F.G. Rol de la enfermería en el apoyo social del adulto mayor. Enferm. Glob. 2010, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Mayoralas, G.; Schettini, R.; Sánchez-Román, M.; Rojo-Perez, F.; Agulló, M.S.; Forjaz, M.J. The role of gender in ageing well a systematic review from a scientific approach. Prism. Soc. 2018, 2, 149–176. [Google Scholar]

- Arias, C.J. La Red de Apoyo Social en la Vejez. Aportes para su Evaluación. Rev. Psicol. IMED 2009, 1, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

| n | Range | M | SD | Cronbach’s Alpha | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social support | 137 | 1–5 | 3.93 | 0.74 | 0.82 |

| Confidential | 137 | 1–5 | 3.78 | 0.82 | 0.78 |

| Affective | 137 | 1–5 | 4.20 | 0.79 | 0.70 |

| Life satisfaction | 137 | 1–7 | 4.99 | 1.27 | 0.81 |

| Self-esteem | 137 | 1–5 | 3.14 | 0.50 | 0.71 |

| Perceived general health | 137 | 1–100 | 67.04 | 18.94 | - |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | |||||||

| 0.35 ** | - | ||||||

| 0.23 ** | −0.17 | - | |||||

| 0.19 * | −0.16 | 0.95 ** | - | ||||

| 0.26 ** | −0.16 | 0.83 ** | 0.62 ** | - | |||

| 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.34 ** | 0.34 ** | 0.24 ** | - | ||

| −0.08 | 0.12 | 0.21 * | 0.23 ** | 0.11 | 0.19 * | - | |

| −0.23 ** | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.12 | −0.01 | 0.22 * | 0.19 * | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Farriol-Baroni, V.; González-García, L.; Luque-García, A.; Postigo-Zegarra, S.; Pérez-Ruiz, S. Influence of Social Support and Subjective Well-Being on the Perceived Overall Health of the Elderly. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5438. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105438

Farriol-Baroni V, González-García L, Luque-García A, Postigo-Zegarra S, Pérez-Ruiz S. Influence of Social Support and Subjective Well-Being on the Perceived Overall Health of the Elderly. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(10):5438. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105438

Chicago/Turabian StyleFarriol-Baroni, Valeria, Lorena González-García, Aina Luque-García, Silvia Postigo-Zegarra, and Sergio Pérez-Ruiz. 2021. "Influence of Social Support and Subjective Well-Being on the Perceived Overall Health of the Elderly" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 10: 5438. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105438

APA StyleFarriol-Baroni, V., González-García, L., Luque-García, A., Postigo-Zegarra, S., & Pérez-Ruiz, S. (2021). Influence of Social Support and Subjective Well-Being on the Perceived Overall Health of the Elderly. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(10), 5438. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105438