1. Introduction

Successful sustainable development meets the needs of the present without compromising those of future generations [

1,

2,

3]. Traditional conceptions of sustainability are typically rooted in the triple bottom line, which includes three major dimensions: social, economic, and environmental [

4,

5,

6,

7]. According to Khan [

8], various factors related to these three dimensions are used to describe those who tend to exploit sustainable development. The social dimension of sustainability includes factors such as safety, health, and social concerns [

4,

5]. On the economic front, Svensson and Wagner [

7] highlighted factors such as profits and business dynamics. Brocke et al. [

9] and Gevrenova [

10] stressed the substantial role of green businesses in pursuit of environmentally friendly and sustainable development. The environmental dimension of sustainability covers ecological degradation, carbon labelling, product dematerialisation, and efficiency improvement programmes [

7,

11]. It has been argued that entrepreneurs, or more specifically, green entrepreneurs, who aim to achieve both business and environmental goals, have a transformative influence on their sectors and play a major role in sustainable development [

12,

13].

As a driving force for institutional development, entrepreneurship plays a critical role in shaping domestic industries, systems, and networks. Due to systemic forces and institutional variations, however, the degree of influence exerted upon the overarching industry is conditional and heterogeneous across national borders [

14,

15]. Although analyses of the relationships between institutional factors, entrepreneurship, and development are proliferating, most of the literature remains framed by traditional views such as endogenous growth and Schumpeterian theory [

15]. Considering green entrepreneurial activities within the (sustainable) development process requires expanding our perspective, as green entrepreneurs are a part of complex sociotechnical networks and are impacted by other actors, social institutions, policies, and regulations. Zahraie et al. [

16] found that green entrepreneurs struggle to break through dominant trends, but regulative support at appropriate moments may help this transition by promoting a vision for collective action. Similar findings were reported by Demirel et al. [

17], who suggested that governments play a large role in giving green entrepreneurship legitimacy by awarding contracts, enforcing environmental legislation, or facilitating financing. Yi [

18] observed that university-level support of green entrepreneurship fosters an enabling environment for green businesses. Such prior research confirms a positive relationship between green entrepreneurship and green enterprise that is systemically linked to the oversight of governmental support in developing nations. Although scholars in this field have provided evidence supporting the link between environmental entrepreneurship and sustainability in developed economies [

16,

19], a lack of evidence and academic emphasis on developing countries such as Saudi Arabia raises questions as to the efficacy and transferability of such developmental propositions.

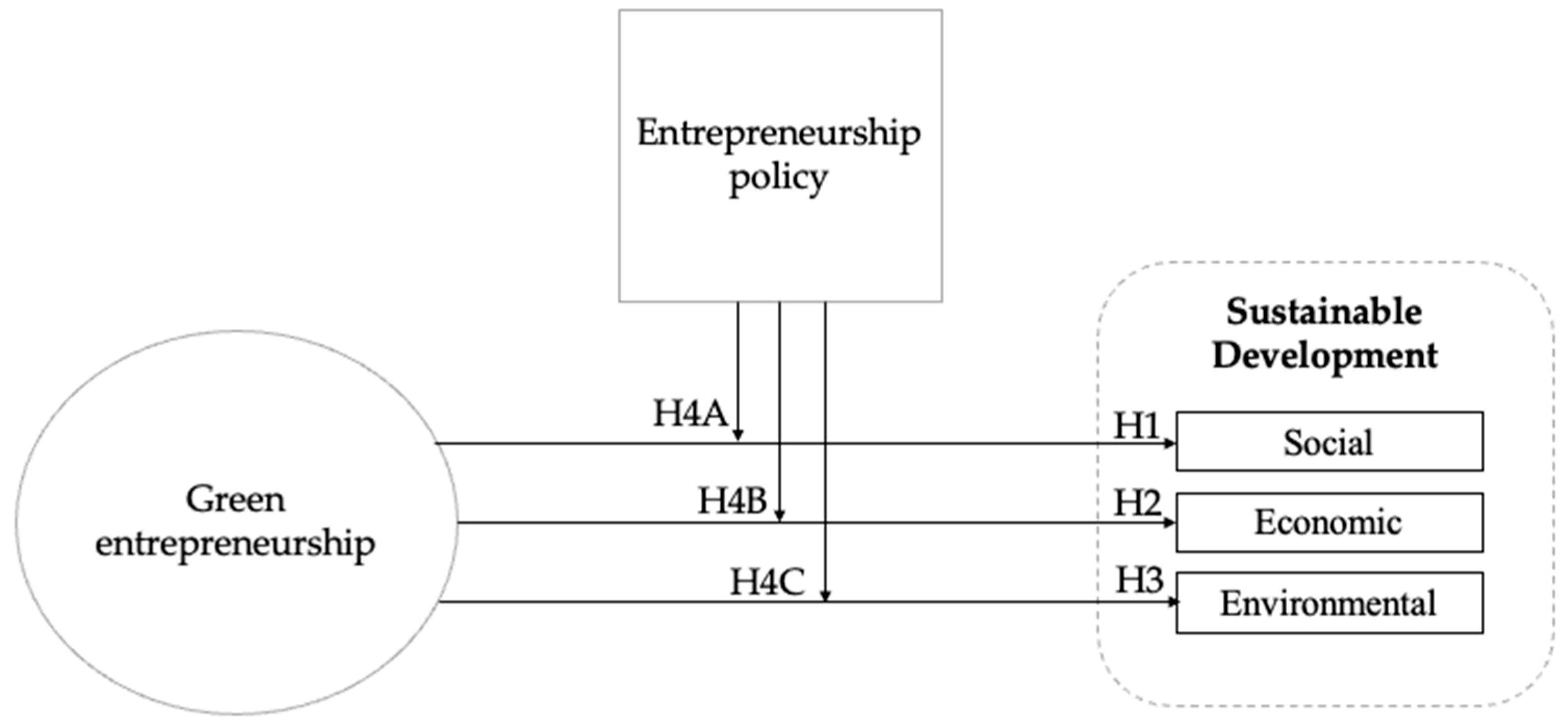

Therefore, the primary aim of this study is to explore the influence of green entrepreneurial activity on sustainable development. Also, the role of entrepreneurship policy is analysed in the context of Saudi Arabia. In accomplishing this aim, institutional economics [

20] is used as the theoretical foundation of this research to help us understand the relationship between green entrepreneurship and sustainable development. The utilisation of institutional economics enables us to observe the phenomenon from a different angle, which considers the existence of external factors (e.g., policies) affecting the association of green entrepreneurship with sustainable development. This relationship is tested through panel data models from 13 Saudi Arabian cities during the period from 2012–2017.

Predicting a strong, statistically significant relationship between domestic policies in Saudi Arabia, green entrepreneurship, and the triple bottom line, this study has critically explored time-series evidence from a selective array of multiregional proxies. Using information from the General Authority for Statistics (GAS) in Saudi Arabia, these findings confirm a precipitating relationship between green entrepreneurship and downstream transformation of social, economic, and environmental agendas. Furthermore, this study confirms the role of domestic entrepreneurship policies in supporting and directing entrepreneurial activities toward greener, more sustainable industry outcomes.

Different implications have been derived from this study. First, the influence of green entrepreneurship on sustainable development was analysed by comparing the affective influences of green and nongreen entrepreneurial initiatives on industry outcomes. Second, empirical evidence regarding the social, economic, and environmental advantages of green entrepreneurship were identified, providing a developmental blueprint for improving intra-industry outcomes in future Saudi Arabian ventures. Third, these findings shed light on the differences in approaches towards green entrepreneurship and sustainable development in different regions of Saudi Arabia, highlighting the contagion effect of cross-national knowledge sharing for sustainability in a rapidly developing economy. Finally, the study extends previously available frameworks such as endogenous growth theories and the Schumpeterian theory of entrepreneurship by treating sustainable development as a composite index of economic, social, and environmental dimensions [

21]. It also addresses a gap in the existing literature regarding the systemic influence of national regulatory policies on green entrepreneurship and domestic sustainability in Saudi Arabia.

The following section introduces the theoretical framework.

Section 3 discusses the conceptual foundations of the literature review and the development of the hypotheses. In

Section 4, the methodology and data are explained, and the findings are presented in

Section 5. Finally,

Section 6 comprises the study’s conclusions, implications, limitations, and suggestions for further research.

2. Institutional Economics, Green Entrepreneurship, and Sustainable Development: A Framework for the Saudi Arabian Context

To comprehend the possible mechanisms behind the relationship between green entrepreneurship and sustainable development, this study adopted a paradigm of institutional economics [

20,

22], a widely utilised theoretical lens for entrepreneurship research on the role of interactions and choices in economic evolution [

15,

23,

24,

25,

26]. Elaborating on this viewpoint, scholars have explored institutions as antecedents of entrepreneurial activity, as well as their relationships with economic growth [

3,

15,

27,

28,

29]. Drawing on North [

20], institutions are perceived as the source of rules guiding interactions amongst different actors (including firms). Accordingly, the existence of certain institutions creates divergence across regions and countries, as cultures and regulations define different patterns governing production and consumption decisions. For example, North [

20] finds differences between Western and Eastern economies, as well as Anglo-Saxon, Scandinavian, German, etc., countries. Although most of the prior research has focused on developed economies [

15], there is still a need to understand how institutions work in other places, which might impose barriers to entrepreneurship in different ways [

8,

30]. Hence, the present study focuses on formal institutions in Saudi Arabia because these more readily inform the decisions of the country’s policymakers.

Saudi Arabia is a strategic and important nation in the Middle East and the world [

31,

32,

33,

34]. Saudi Arabia is the largest economy in the Middle East and the richest Arab country in the region [

34,

35,

36]. Petroleum products represent a large majority of exports (77% of total exports in 2019), followed by petrochemical products (around 14% of total exports) [

33,

34,

37]. Machinery and electrical equipment account for the largest share of imports, followed by automobiles, chemical products, and metal products [

33,

34,

38,

39]. The policy of large-scale public works undertaken by the authorities, as well as foreign direct investment, means that Saudi Arabia needs to provide governmental supportive policies for green entrepreneurial activities and sustainability. This supports and promotes the aim of reducing the vast overreliance of the economy of Saudi Arabia on oil [

40].

Government policies help to establish conditions for boosting environmentally friendly entrepreneurship [

41]. The need for development through entrepreneurship has to be balanced with the need to preserve the opportunity for future generations to reach and enjoy a high quality of life and to sustain the environment; this is what the Saudi Arabian government is trying to achieve. The vision for Saudi Arabia in 2030 [

42] includes a suite of government-level policies that support economic and social improvements. A particular focus of the Saudi Arabian government and the executive has been to reduce the country’s dependence on oil as one of the major industries and to diversify into other sectors such as clean energy, health, and tourism. Green entrepreneurship and a focus on a holistic approach to economic development that balances people, profit, and planet is thus a cornerstone of Saudi Arabia’s long-term national strategy [

43]. Additionally, environmentally sustainable practices develop the social and economic performance of firms in the long term [

44].

The policies adopted by Saudi Arabia are consistent with the growing need to address environmental threats and to protect the environment. The work by Yi [

18], Alwakid et al. [

43], and Ndubisi and Nair [

45] suggests that there is a need for companies to adopt a green approach. In developing countries, environmental actions are of prime importance [

46]. However, it is not clear whether the actions of the Saudi Arabian government are leading to their intended effects. It is possible that the government either uses resources inefficiently or faces obstacles in implementing environmental policies. For this study, it was critical for additional research related to Saudi Arabia to illuminate whether institutional effects support green entrepreneurship, or whether other factors influence the progression from traditional to sustainable enterprise.

5. Results

The key descriptive statistics for the variables are shown in

Table 1. Economic factors varied from −2.247–3.484 (M = 0.000, SD = 1.653). Social factors ranged from −2.526–4.044 (M = 0.000, SD = 1.578). Environmental factors ranged from −2.566–2.992 (M = 0.000, SD =1.627).

Pearson’s correlation revealed that some of the variables had significant positive relationships and others insignificant relationships. For example, environmental factors showed a strong correlation with green entrepreneurship (r = 0.916), whereas there was a moderate correlation between social factors and nongreen entrepreneurship (r = 0.643).

Table 2 shows that both green entrepreneurship and nongreen entrepreneurship were highly correlated with the components of sustainable development. The correlation between independent variables was moderate to low, suggesting that there were no multicollinearity problems in the sample. Entrepreneurship policy did not appear to be correlated to the components of sustainable development.

Table 3 illustrates a synthesis of the key results for all of the panel data models with fixed effects evaluating social, economic, and environmental dependent variables (see

Appendix C,

Appendix D and

Appendix E). Only the controlled variables were included in models 1, 4, and 7. The other three models (2, 5, and 8) were then set, each with one predictor representing each hypothesis. Finally, additional models (3, 6, and 9), which included all predictors (i.e., independent variables, controls, and the interaction terms) were explored. Throughout this empirical strategy, tests were performed to assess whether different linear combinations created different results or whether a robust specification was found; the full tables are presented in

Appendix C,

Appendix D and

Appendix E.

Regarding the hypothesis testing, there was a positive association between green entrepreneurship, nongreen entrepreneurship, and sustainable development in different regions of Saudi Arabia, so H1 was not rejected. These findings confirmed that green entrepreneurship had a significant positive effect on the dependent variable in the full model (2.179,

p < 0.01), whereas nongreen entrepreneurship had a nonsignificant effect. H2 argued that green entrepreneurship had a higher influence on the economic dimension of sustainable development than nongreen entrepreneurship. The evidence indicated that green entrepreneurship was positively related to the economic dimension. As with Pozdniakova [

70], this study demonstrated that green entrepreneurship had a significant positive influence on the dependent variable in the full model (1.220,

p < 0.05), whereas nongreen entrepreneurship had no significant impact on economic factors; this was consistent with H2.

The third hypothesis, H3, suggested that green entrepreneurship had a higher influence on the environmental dimension of sustainable development than nongreen entrepreneurship. Green entrepreneurship was positively associated with the environmental dimension, so H3 was fully supported. This was consistent with the empirical findings of Svensson and Wagner [

7]. In addition, the results indicate that green entrepreneurship had a significant positive influence on the dependent variable in the full model (1.117,

p < 0.01), whereas nongreen entrepreneurship had a non-significant negative influence. Thus, only green entrepreneurship appeared to boost the environmental component of sustainable development.

Concerning interactions, H4A suggested that entrepreneurship policy has a positive moderating influence on the relationship between green entrepreneurship and the social dimension of sustainable development. The interaction term for green entrepreneurship was not statistically significant; therefore, green entrepreneurship was found to have a similar influence on social factors regardless of entrepreneurship policy, so H4A was rejected. As Prasetyo and Kistani [

25] suggested, the link between social entrepreneurship and social capital under conditions of low government activism and rising domestic competitiveness might explain the lack of influence of entrepreneurship policy on the relationship between green entrepreneurial activity and the social dimension of sustainable development.

H4B posited that entrepreneurship policy has a positive moderating influence on the relationship between green entrepreneurship and the economic dimension of sustainable development. Despite green entrepreneurship having a significant positive influence on the dependent variable in the full model, the interaction term for green entrepreneurship was negative and significant at the 0.10 level, suggesting that the influence of green entrepreneurship on economic factors decreased with the quality of entrepreneurship policy. This contradicted H4B. This might be explained by the type of incentives offered in the entrepreneurship policy, which might encourage other types of firms with less environmental consciousness [

75].

We suggested in H4C that entrepreneurship policy has a positive moderating influence on the relationship between green entrepreneurship and the environmental dimension of sustainable development. Even though green entrepreneurship positively explained the dependent variable in the full model, the interaction term for green entrepreneurship was not significant at the 0.10 level. This might indicate that the positive impact of green entrepreneurship on environmental factors did not depend on the quality of entrepreneurship policy, thus contradicting H4C. Thus, only green entrepreneurship appeared to boost the environmental component of sustainable development, which is consistent with the extant literature [

7,

63].

In summary, a comparison of H1, H2, and H3 showed strong significant relationships between proactive green entrepreneurship and social, economic, and environmental outcomes, but the data suggested that nongreen entrepreneurship had a non-significant effect. It was therefore concluded that, overall, there was a statistically significant relationship between green entrepreneurship and sustainable development outcomes.

To affirm these results, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated as a measure of internal reliability of the Likert-scored elements of the research instrument (innovation and environment policies). Cronbach’s alpha, denoted by α and calculated by the Equation (2)

is a measure of internal reliability and consistency. It contained the following elements in the present instance: a count of the items (2), a count of the sum of the items (343), and a sum of the variance of the items (16.35). Unfortunately, there appeared to be limited internal reliability. Possible explanations for this include gaps in the data and uncertainty over their interpretations in different regions. Further studies would therefore be necessary to determine causality, as has been previously discussed.

6. Conclusions

Prior research regarding the association between green entrepreneurship, nongreen entrepreneurship, and sustainable development in Saudi Arabia is limited. This study has illuminated a positive, regionally heterogeneous relationship between green and nongreen entrepreneurship and sustainable development. In particular, green entrepreneurship had a stronger influence than nongreen entrepreneurship on all the dimensions of sustainable development. Our results are consistent with previous studies that have shown tight links and interrelations between green entrepreneurship and sustainable development [

2,

47,

48]. The findings also correspond with more recent work that has recognised the bidirectional nature of green entrepreneurship and sustainable development in urban contexts [

50,

52].

By contrast, the results on the moderating influence of entrepreneurship policy were mixed. None of the three corresponding hypotheses were confirmed, indicating that a domestic policy does not have a positive moderating influence on the relationship between green entrepreneurship and sustainable development. Interestingly, a negative moderating influence was found for the economic component of sustainable development. This could suggest that existing entrepreneurship policies in Saudi Arabia may impair the positive influence of green businesses on the country’s economic sustainability. When viewed through the lens of institutional economics, the results can be considered consistent with the work of Urbano et al. [

15], in that business was hindered by high levels of corruption and weak property rights. As North [

22] reminds, it is possible for institutional support to be focused on economic growth. This could have a negative moderating influence and might explain the outcome of H4A–H4C. Yet, our results might support a debate offered by Yi [

18], who emphasised the role of external institutional support in translating green entrepreneurship intentions into actions.

The lack of a moderating influence of entrepreneurship policy on the link between green entrepreneurship and economic and environmental factors might reflect the degree of sustainability awareness amongst both producers and consumers [

52]. Alternatively, a non-significant effect represents a net zero impact of positive and negative externalities of governmental policies. The Saudi Arabian government may not be providing adequate instruments for green entrepreneurs to deal with existing risks and uncertainties, which will impair sustainable development [

41,

74]. Hence, our analysis may serve to derive theoretical and policy implications.

6.1. Theoretical Implications

Green entrepreneurship is a novel field of research, so further exploration is needed with respect to the role of entrepreneurial activity as a means of sustaining the environment and ecosystems, while advancing both economic and non-economic gains for investors and society in general [

89,

93]. Research into the influence of formal institutions on certain outcomes in green entrepreneurship should be founded on theory. The present study has advanced knowledge in the field, in that it has tested existing theoretical propositions robustly and comprehensively and has confirmed the role of green entrepreneurship in sustainable development. We also consider that our empirical findings may better guide scholars studying Saudi Arabia to help entrepreneurs to become more aware of sustainability policies. It may also serve to encourage the advertising of outcomes related to sustainability as a way of increasing the legitimacy of policies and generating the support of entrepreneurs.

In addition, it builds on the work of Potluri and Phani [

21] and Huang et al. [

59] by pointing to the impossibility of parsing sustainability and the development of the financial sector development in the current context. Our results serve to call the attention of those scholars analysing entrepreneurship from an institutional perspective [

15]. Accordingly, we extend the notion of entrepreneurship with environmental purposes as an antecedent of outcomes beyond economic terms. This implies that our evidence of Saudi Arabia can exemplify the conceptual structure, which suggests that institutions determine green entrepreneurial activity needed for social, economic, and environmental development [

100].

6.2. Policy Implications

The findings of the present study are consistent with Khan [

8], who claimed there were not enough associations and institutions in Saudi Arabia lobbying for sustainable business practices. Therefore, policies designed by the relevant Saudi authorities might not be taking into account important entrepreneurship networks. This could reduce the number of opportunities for new businesses and impair the development of green entrepreneurship in the country [

13,

17]. Saudi Arabia only has a small number of business incubators [

8], which may limit the availability of value-added assistance for green entrepreneurs [

85].

Government can affect the engagement of entrepreneurs by helping them in their understandings and applications of sustainable development policies. There are other important implications for the analysis of formal institutions [

20,

22]. For example, if green entrepreneurs have strong bonds with governments, they feel valued by local and national entities, so their opinions and actions are positively considered in sustainable developmental processes. Government support for green entrepreneurship allows for a more sustainable environment, and can be the first step toward a more environmentally conscious society and for the conservation of resources for future generations. The government of Saudi Arabia, in particular, should continue to promote such policies.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Central to the indicators of sustainability, the current study applied an array of prior models and proxy dimensions to assess the particular traits of the Saudi Arabian social, economic, and environmental systems. Furthermore, institutional conditions were measured in relation to incongruous incentivisation schemes and scalar comparisons of cross-geographic indicators of entrepreneurship. These approaches, although yielding a diversified quantitative model, resulted in several critical limitations that have skewed and diluted the efficacy of these findings. For example, H4A–H4C were rejected due to the inconsistent effects of policy measures on green entrepreneurship. This limitation, however, is likely linked to the proxy indicators, a constraint that will be reconciled in future research where government performativity is used to track progress towards Vision 2030 sustainability objectives. Another example of a proxy-based limitation in this study was the assumption of relational causality between input–output variables. The measure of nongreen entrepreneurship, for example, was based upon an assumption of a direct correlation between high pollution rates and nongreen business activities. This indicator implies distinction between green and nongreen businesses on the basis of carbon footprint, but does not control independently for size or industry of enterprise. It is recommended that future researchers test the relationship between green entrepreneurship and sustainable development by using different proxies for social, environmental, and economic aspects to ensure confidence in the policy application of their findings. By weighting the effects of specific policy measures in developing nations such as Saudi Arabia against sustainability indicators over longitudinal models of green entrepreneurship or domestic sustainability, it is predicted that future evidence will confirm the affective influence of targeting strategies on social, economic, and environmental outcomes. Finally, future research could carry out more cross-sectional and longer-term analyses by investigating evidence from other developing countries within the GCC region and by extending the present study’s six-year time frame.