Perception, Attitudes, and Experiences Regarding Mental Health Problems and Web Based Mental Health Information Amongst Young People with and without Migration Background in Germany. A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

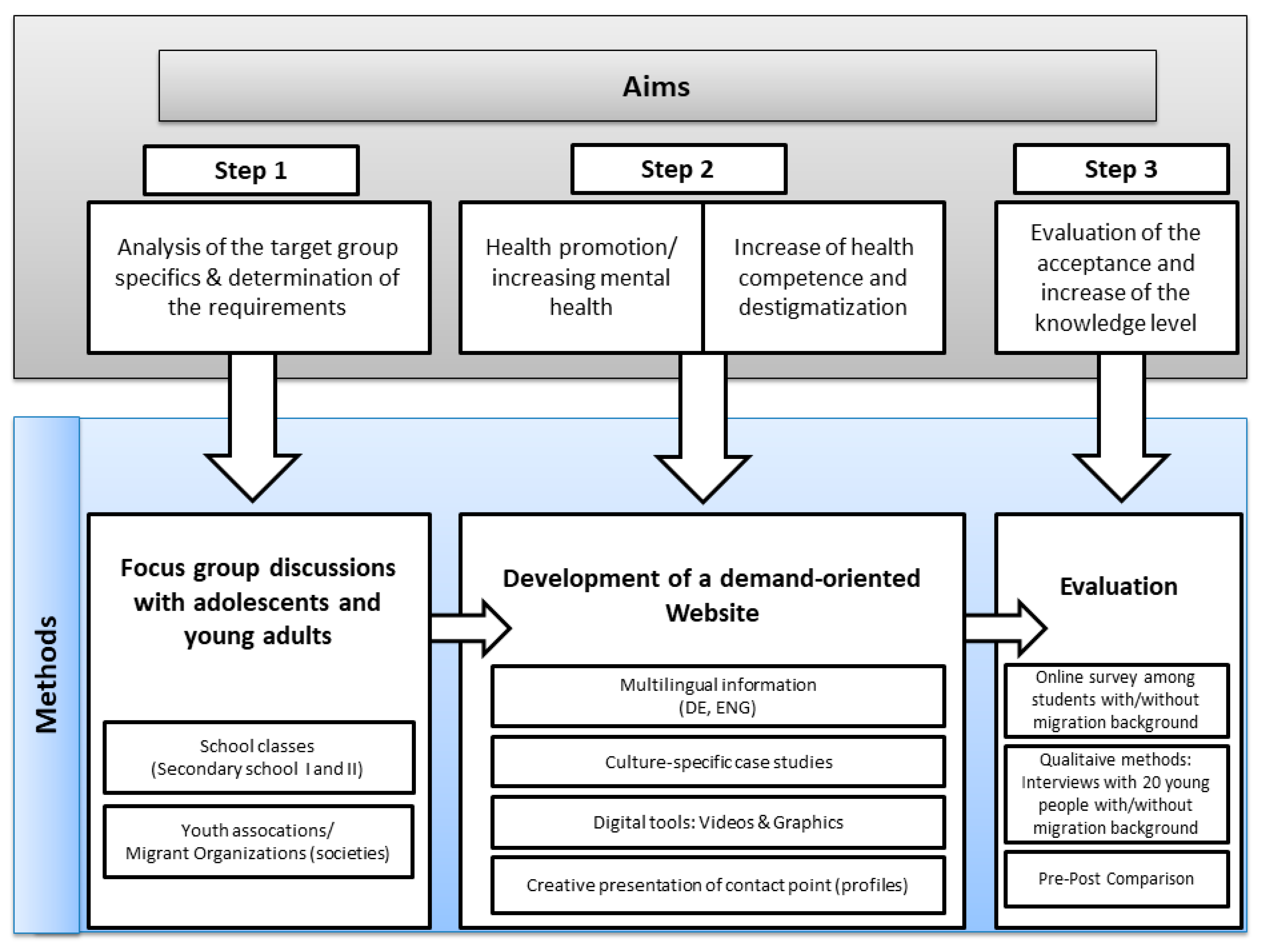

- The health literacy for the mental health of adolescents and young adults with and without a migration background is to be promoted through the information on the website.

- The target group should be sensitized to the relevance of psychological problems and illnesses regarding themselves and their environment (peers), thus preventing chronification.

- Through the presentation of diverse case studies, an understanding of the individual approach to mental health and illness is achieved, which in turn leads to a reduction in stigmatizing behavior and an increase in the compatibility of the topic of mental health with the everyday life of young people.

- The website should provide an impression of trustworthiness and professionalism so that visitors are encouraged to deepen their knowledge about mental illnesses and are able to cope with previously challenging or overwhelming situations.

- In the long term, this should help to improve the health and quality of life of the target groups.

- This study refers mainly to Step 1 and summarizes ideas from its results that will be incorporated into Step 2 (see Figure 1).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Focus Group Discussions (FGD) and Guideline Development

- Everyday life of young people (challenges; the reality of life):The participants were generally asked how they were doing in everyday life, whether there are things at school, at work, or in the family that stress them. They were also asked how they deal with possible problems and challenges.

- Procurement and understanding of health-relevant information:It was discussed where and how the participants obtain information on health topics. In addition, specific information formats such as texts, videos, etc., were addressed in order to determine preferences, among other things.

- Importance of mental health (experiences and handling):Previous experiences with mental illnesses in the personal environment and general interest in psyche were discussed. In particular, the need for information and the evaluation of the information found with regard to comprehensibility and usefulness were addressed.

- Demands on digital services in general and in the context of mental health:Participants were asked for websites and apps that are used in everyday life. They were also asked what they like about these diverse digital possibilities and possibly also media people, e.g., on YouTube, and what they do not like and to what extent there is room for improvement. Of particular interest was the question of the seriousness, trustworthiness, and quality of online offerings. Additionally they were asked about their use of chat rooms or forums as well as quizzes or playful offers on websites.

2.2. Participant Recruitment

2.3. Implementation of the FGD

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Experiences with Mental Illness

“I can imagine that every second person in this school has problems or knows people who have problems with something like that. I think it would be really helpful if there was a psychology subject in school. Then you already learn about it in young age. You would be able to help those affected in some way.”(female, 18 years old, with migration background (wMB)

“Well, I just wanted to say again that I am in favor of everyone seeing a psychologist. And I also think that you should not necessarily call it a psychologist, because the word is always a bit negatively afflicted with wrong ideas. Instead, everyone should be entitled to a kind of life coach. This person should of course have a professional training, because you can get a lot out of personalities if you work on them for a bit. It doesn’t necessarily always have to be that someone only has one blatant problem but that you also find something else to work on.”(female, 29 years old, without migration background)

3.1.1. Supply Deficits and Consequences

“If you have to go to a psychologist or something like this, you often have to go to a general practitioner first to get a medical certificate. Additionally you have to wait for months until you get an appointment. And people often need acute care. Sometimes it is really urgent, and I think in this case using the internet as an interim measure until an appointment is actually made—there is nothing wrong with that. But as I just said, it is often the case that during this time so many influences can have a negative impact, that it is sometimes too late…three months ago it was too late for a friend of mine and she threw herself in front of a train. She waited. She had an appointment…and it was so acute and yes, that’s when she decided to commit suicide. And I simply believe an interim solution definitely has to be provided.”(female, 28 years old, without migration background)

“I have a friend who came to see me last week. And one night he got some bad news: His friend had killed himself. He is from Afghanistan, and his asylum application has been rejected. And I think he had been in Germany for four or five years. My friend told me, ‘Yes, he suffers from depression.’ For already, I think, a year or something like that. […]. For example, ‘I feel very bad and I need someone who always listens.’ But my friend told me, ‘You know what, when you listen to him, you feel bad yourself.’ And because of that, no one wants to help him. Because there’s a bad feeling coming back. But after he had killed himself, all friends were like, ‘We wish we could listen to him just once more one time,’ and things like this. But now it’s all over and… I think that these people, who suffer from depressions, always need someone who listens and comforts. But I think refugees have no one like that, and that’s why it´s so hard.”(male, 23 years old, with migration background and refugee experience)

3.1.2. Attitudes and Modes of Behavior

“In some cultures… there is simply no such thing. So as soon as you start talking about not being well, even though there is no particular reason or you have dark thoughts or even think about death, they you say, ‘That’s bullshit. You are fantasizing it. You are simply imagining it to yourself. That is not true and so on. You have everything.’ You are accused of such things…. If you are already introverted and sad anyway, if you have depressions or something like that, then you tend not to say anything anymore. Also to friends or to doctors or somebody else. Because it’s your own parents. So if they already speak against you, what else should a doctor do.”(female, 18 years old, with migration background)

“That’s exactly how it was with me. I didn’t tell my mother either and tried to do it myself, because I knew that she would say that I am just crazy. Of course I am crazy. that literally was the problem.”(female, 29 years old, without migration background)

“I personally think this topic is still too quiet. Far too quiet. And I think society needs to be sensitized much more to this topic. I also think that these people deserve to be heard and that they should not be treated with contempt. That they are taken seriously. And that people shouldn’t dismiss it and say, ‘Oh come on, he has his little ailments there’ or ‘But I also have my problems’.”(female, 28 years old, without migration background)

“Yes, you can also offer a target in some way. Even if you don’t expect to be attacked by your family or friends, but still.… You give something of yourself away.”(female, 21 years old, without migration background)

3.1.3. Problems with Knowledge Platforms and Mistrust on Social Media

- WhatsApp (communication medium; “You can’t do without it”; otherwise you are excluded; what makes it special is that it is free and fast)

- Instagram (serves as a distraction; but also: dangerous ideals are presented there—both in terms of body ideals and lifestyles such as vacation photos; “perfect”, exciting life)

- YouTube (both as “problem solver” and for fun)

- Facebook (named as a contrast to Instagram: Networking through groups, events and sales; criticism: flood of information that doesn’t interest you at all)

“Well, I think such forums would make sense, because there is such a thing, where you can call, no matter what the topic is. There is still a bit of inhibition threshold, if you really call this anonymous number or not. And you don’t know who is on the phone right now. Does the person really understand you? Then sometimes it is perhaps easier to explain in writing how you feel than on the phone.“(female, 28 years old, without migrant background)

3.2. Cultural Differences (Attitudes and Gender Differences)

“Again, about this thing in our home country, so I think in most countries, which is so Muslim, when a woman as an unmarried woman—if you are depressed or crying somehow—everyone says: ‘Yes, sure! She longs for a man.’ And then when she is married, everyone says, ‘Yes, she doesn’t like her husband. Apparently, she has a lover.’ In other words, it’s always viewed from a different perspective, a different position on the matter, and not what’s really there, what her problem is.”(male, 23 years old, with migration background and refugee experience)

“So they say, ‘Oh God, the poor man has worked so hard and suffered so much! He took care of the whole family and made sure they got something to eat. Of course you go crazy.’ Yes, with men it’s always a matter of course, ‘Oh, the poor guy!’, and with women, ‘Are you in love? Well, are you longing for a man? Would you like a man right away?’ Or, if you already have a man, ‘Well, are you in love with his brother?’ Right, it’s always like that. They don’t realize what their problems really are.”(male, 23 years old, with migration background and refugee experience)

“So there is a girl, she is about 25 years old. She has already studied the whole Koran. She was finished and took several courses, so… language courses. And has her diploma and everything.… At that age it’s marriageable age there.… She still hasn’t married. And she was acting a little bit strange. And all her parents and her family, her neighbors see her as mentally ill because she behaves a little bit different. And they say okay, I say ‘eye’ or it’s magic, witchcraft. Or because she didn’t marry… that she has a jinn in her body.”(female, 20 years old, with migrant background)

3.3. Media Use in the Context of Mental Health Problems

3.3.1. Search Strategies

“Sometimes there is the short thought, ‘I need help’, but then it’s gone again. The hurdle is too big, to get information would be too much effort.”(female, 23 years old, without migration background)

“When searching on google, the problem is that google shows those things first an average user concerns most or what has been viewed most. This means, when starting something new you need the help of our main media providers for advertisement to be found.”(male, 22 years old, without migration background)

“Well, I first looked for the diagnosis and then for what was available on the Internet. And then there were sites like Netdoktor or Onmeda. There they focus on medication, on symptoms and then at the bottom they provide a reference: So that you can contact a specialist or something like that. There also exist self-help groups and stuff like that. But, yes it wasn’t really personal. So I did not feel addressed.”(male, 20 years old, with migration background)

3.3.2. Needs

- First of all, that it has to be a serious offer with contents of concerned persons and professionals, which are personally presented. Because only personal stories from other affected people can help and inspire, but are not enough. A professional person has to provide content as well.

- The identification with the offer must be simple, the question, “Am I right here?” should be answered directly.

- The offering should motivate people to move out of the digital world and initiate personal meetings. There should be a very clear indication that this is no substitute for therapy. This should pave the way to therapy.

- A critical enlightenment is seen as advantageous, especially that a demarcation from and esotericism takes place, whereby mindfulness is especially emphasized as clearly helpful.

- The use of questionnaires or checklists was affirmed: Is help needed? If so, which form? Possible diagnosis?

- Videos are interesting for the target group, it was stressed that they should be short. Texts are preferred because they can be skimmed over independently and quickly classified.

- A quiz, on the other hand, is viewed rather critically (“What’s the point?”; the topic is too serious for a game)

- Statistics can show (if they are chosen well): I am not alone in this.

- Important facts should be pointed out: What can I do? How long does it take? Where can I find help? What are the consequences? What can positive prospects look like?

- When linking to regional offers sufficient information is very important!

- It is important to remember that telephoning can be difficult or that the surroundings of an institution or how to get there can be crucial for the decision for or against this institution.

“My sister already had therapeutic treatments.… And I ask myself, What is actually discussed in these hours? Is there a dialogue or a monologue taking place?”(female, 28 years old, without migration background)

3.3.3. Quality Factors of Websites

3.3.4. Impact/Benefit of a Website

“Okay I don’t have this backbone at home. For whatever reasons, you should at least have the possibility to get help elsewhere if you want to. If it is not given at home. Because I think you have to get help somewhere and I see it as a must. So as I said, this is not only a privilege, it should really be part of it like breathing, eating, sleeping. Just like first aid. If I feel bad, I call an ambulance. That is with us if I feel bad, I call the ambulance. And I think this help… should not only be physical help, but also mental help.”(female, 28 years old, without migration background)

“That you even open up a third section where the children really say “Mom, watch out. Ehm maybe you don’t quite understand it all. Here is this page. You can simply write it down, give it to them and the parents will be able to visit this page. The page alone will be very meaningful and afterwards, when the parents have read it, they might be like, ‘aha my daughter or my son is not the only one. And there seems to be something wrong.’ This way you have the possibility to communicate with your parents. It’s sad when you don’t have it face to face.… But maybe this is the first step.”(female, 28 years old, without migration background)

3.3.5. Advantages and Risks of a Diagnosis

“In my opinion, diagnoses do have a value. They can indeed be helpful. At first you don’t know what your problem is, and therefore don’t know how to go against it. You simply don’t know where to start. The diagnosis gives you a name to work with. Now you can start to get rid of it. That’s why it is a good starting point. If you don’t understand what’s wrong, you first need to identify the basic problem, which is a problem in itself.”(male, 25 years old, with migration background)

“I also think so. In my opinion, it is very, very dangerous to only use the internet, especially when you immediately trust everything you read. When it comes to mental problems it can be very complex and experts are needed to watch over it. You can’t try to identify and understand every term by yourself, just to estimate your own position. I don’t like that. Most of all, if you do it this way, you automatically apply a negative identity to yourself and get into it way too much. You could develop even more symptoms, just because they fit the diagnosis you just found. Your behavior will change depending on the illness you think you have.”(female, 24 years old, with migration background)

3.3.6. Disturbing or Triggering Contents and Responses

“I think that really was the worst thing I could do at that time…. Well, my friends and others teased me in school always saying that I’m depressive. That was when I first entered the word depression into Tumblr. Immediately images of arms that where cut open appeared. Below it where words like, ‘It did so good. I feel better I’m not sad anymore, the pressure’s off.’ And as a 14-year-old, when you look at something like that, you think, ‘Ah okay, maybe it’ll help me. I’ve been struggling with this for so long. This is the way out.’ Now when you’re a little bit older of course you think differently, but when you’re that deep in it at that age, everything pulls you along. Today I would do it completely different… accordingly I would not even enter something like that. Especially not on pages like Instagram, Tumblr, Facebook, or such. Even on Google. If you type in depression and go to pictures, you will immediately get such pictures of self-harm. Immediately. You won’t get a table with things you can do to distract yourself or with skills that help you if there is the pressure to hurt yourself. There are only these pictures of self-harm. Pictures of people crying. Things like that.”(female, 18 years old, with migration background)

4. Discussion

4.1. Mental Illness and Culture

- Faith in the effect of the evil eye

- Belief in the effect of magic or sorcery

- Faith in the effect of other beings, the jinn

4.2. Mental Illness and Gender

4.3. New Website to be Developed

4.3.1. Properties of the website to be developed/Elements of the website

- To improve the mediation of psychological content, which can be quite complex, multimodal processing is necessary. This made it clear that texts and videos are in demand within the target group. Explicitly redundant content, which is, however, presented multimodally—i.e., via different media formats—is desired. For this reason, video clips are to be created with experts who convey complicated content in a comprehensible manner, thus supporting the texts on the website. For each presented disorder, especially depression, anxiety disorders, personality disorders, psychoses and addictions and possibly other disorders (e.g., eating disorders and obsessive-compulsive disorders), several short videos will be produced on the aspects of symptoms, causes, handling, and therapy.

- Another result of the FGD is the demand for graphics. These are to be produced to present complex contents in a simplified way. Just like the videos, they serve to support the text-based content and are created and integrated according to the layout of the site.

- Presentation of all contact points for mentally ill persons and their relatives: The goal is to present the offers on the website in a kind of “profile”, if necessary with photos of the contact points and/or the respective contact persons. In the FGD it became clear that existing information on the Internet was not manageable and could not be checked for seriousness; besides, the needs or hardships of people with acute psychological problems were not addressed.

- During the FGD, the target group expressed the wish for an English version of the website. Here, participants with refugee experience identified English as a common and largely understandable language among young people. Therefore, the content should be provided in English. The information on the website will be kept identical for all. In line with the long-term project goals, it is planned to translate the content into Arabic and, if necessary, Turkish. The aim is to make the necessary information regarding mental health and illness equally accessible to people with and without language barriers.

- What is the problem/burden/illness? (Description of the symptoms)

- How do you recognize this? (Diagnosis)

- How do you treat this? (Showing the treatment options/ways and contact persons)

- What does “mental health” mean and how can I strengthen my resilience? (Integration into the living reality of the target group, education, and practical tips).

4.3.2. Aspects of the evaluation of the new website

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis). Bevölkerung und Erwerbstätigkeit Bevölkerung mit Migrationshintergrund—Ergebnisse des Mikrozensus 2019—Fachserie 1 Reihe 2.2; Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis): Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020. (In German)

- Thom, J.; Nübel, J.; Kraus, N.; Handerer, J.; Jacobi, F. Versorgungsepidemiologie psychischer Störungen. Bundesgesundheitsblatt-Gesundheitsforschung-Gesundheitsschutz 2019, 62, 128–139. (In German) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grobe, T.G.; Steinmann, S.; Szecsenyi, J. BARMER Arztreport 2018 Schriftenreihe zur Gesundheitsanalyse; BARMER: Berlin, Germany, 2018. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- KiGGSStudy Group; Hölling, H.; Schlack, R.; Petermann, F.; Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Mauz, E. Psychische Auffälligkeiten und psychosoziale Beeinträchtigungen bei Kindern und Jugendlichen im Alter von 3 bis 17 Jahren in Deutschland—Prävalenz und zeitliche Trends zu 2 Erhebungszeitpunkten (2003–2006 und 2009–2012): Ergebnisse der KiGGS-Studie—Erste Folgebefragung (KiGGS Welle 1). Bundesgesundheitsblatt-Gesundheitsforschung-Gesundheitsschutz 2014, 57, 807–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert Koch-Institut. Psychische Auffälligkeiten bei Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland—Querschnittergebnisse aus KiGGS Welle 2 und Trends 2018; Robert Koch-Institut: Berlin, Germany, 2018; (In German). [CrossRef]

- Weissman, M.M. Depressed Adolescents Grown Up. JAMA 1999, 281, 1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkevi, A.; Rotsika, V.; Arapaki, A.; Richardson, C. Adolescents’ self-reported suicide attempts, self-harm thoughts and their correlates across 17 European countries: Self-reported suicide attempts by European adolescents. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2012, 53, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewinsohn, P.M. Major depressive disorder in older adolescentsPrevalence, risk factors, and clinical implications. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 1998, 18, 765–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angermeyer, M.C.; Matschinger, H.; Schomerus, G. Attitudes towards psychiatric treatment and people with mental illness: Changes over two decades. Br. J. Psychiatry 2013, 203, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, M.; Marti, L.; Jorm, A.F. The Swiss Youth Mental Health Literacy and Stigma Survey: Study methodology, survey questions/vignettes, and lessons learned. Eur. J. Psychiatry 2019, 33, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, E.R.; McGee, R.E.; Druss, B.G. Mortality in Mental Disorders and Global Disease Burden Implications. JAMA Psychiatry 2015, 72, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik und Nervenheilkunde e.V. (DGPPN). Psychische Erkrankungen in Deutschland: Schwerpunkt Versorgung; Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik und Nervenheilkunde e.V. (DGPPN): Berlin, Germany, 2018. (In Gernan) [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Risks To Mental Health: An Overview Of Vulnerabilities And Risk Factors; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Inchley, J.; Currie, D.; Budisavljevic, S.; Torsheim, T.; Jåstad, A.; Cosma, A.; Kelly, C.; Arnarsson, A.M. Spotlight on Adolescent Health and Well-Being. Findings from the 2017/2018 Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) Survey in Europe and Canada; International Report; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2020; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann, E.; Robert-Koch-Institut. Lebensphasenspezifische Gesundheit von Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland: Bericht für den Sachverständigenrat zur Begutachtung der Entwicklung im Gesundheitswesen; Robert Koch-Institut: Berlin, Germany, 2008. (In German)

- Hurrelmann, K. Psycho- und Soziomatische Gesundheitsstörungen bei Kindern und Jugendlichen. Bundesgesundheitsblatt-Gesundheitsforschung-Gesundheitsschutz 2002, 45, 866–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quenzel, G.; Schaeffer, D. Health Literacy—Gesundheitskompetenz Vulnerabler Bevölkerungsgruppen; Universität Bielefeld: Bielefeld, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen, K.; (HLS-EU) Consortium Health Literacy Project European; Broucke, S.V.D.; Fullam, J.; Doyle, G.; Pelikan, J.M.; Slonska, Z.; Brand, H. Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BZgA–Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung. Gesund aufwachsen in vielen Welten—Förderung der psychosozialen Entwicklung von Kindern und Jugendlichen mit Migrationshintergrund Ergebnisse der Fachtagung der BZgA am 5. Februar 2015 in Essen; Bundeszentrale für Gesundheitliche Aufklärung: Köln, Germany, 2015. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- BZgA–Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung. Förderung der gesunden psychischen Entwicklung von Kindern und Jugendlichen mit Migrationshintergrund; Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung: Köln, Germany, 2013. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Schenk, L.; Ellert, U.; Neuhauser, H. Kinder und Jugendliche mit Migrationshintergrund in Deutschland: Methodische Aspekte im Kinder- und Jugendgesundheitssurvey (KiGGS). Bundesgesundheitsblatt-Gesundheitsforschung-Gesundheitsschutz 2007, 50, 590–599. (In German) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brettschneider, A.-K.; Hölling, H.; Schlack, R.; Ellert, U. Psychische Gesundheit von Jugendlichen in Deutschland: Ein Vergleich nach Migrationshintergrund und Herkunftsland. Bundesgesundheitsblatt-Gesundheitsforschung-Gesundheitsschutz 2015, 58, 474–489. (In German) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okan, O.; Pinheiro, P.; Zamora, P.; Bauer, U. Health Literacy bei Kindern und Jugendlichen: Ein Überblick über den aktuellen Forschungsstand. Bundesgesundheitsblatt-Gesundheitsforschung-Gesundheitsschutz 2015, 58, 930–941. (In German) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleary, S.A.; Joseph, P.; Pappagianopoulos, J.E. Adolescent health literacy and health behaviors: A systematic review. J. Adolesc. 2018, 62, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Röthlin, F.; Pelikan, J.; Ganahl, K. Die Gesundheitskompetenz der 15-jährigen Jugendlichen in Österreich. Abschlussbericht der österreichischen Gesundheitskompetenz Jugendstudie im Auftrag des Hauptverbands der österreichischen Sozialversicherungsträger; HVSV: Wien, Austria, 2013. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Berkman, N.D.; Sheridan, S.L.; Donahue, K.E.; Halpern, D.J.; Crotty, K. Low Health Literacy and Health Outcomes: An Updated Systematic Review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutcher, S.; Wei, Y.; Coniglio, C. Mental Health Literacy. Can. J. Psychiatry 2016, 61, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaeffer, D.; Pelikan, J.M. Health Literacy: Forschungsstand und Perspektiven, 1. Auflage; Hogrefe: Bern, Swizerland, 2017. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Stiftung für Zukunftsfragen; Reinhardt, U. Freizeit Monitor 2020; Stiftung für Zukunftsfragen: Hamburg, Germany, 2020. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Kupferschmitt, T.; Müller, T. ARD-/ZDF-Massenkommunikation 2020: Mediennutzung im Intermedia-Vergleich Aktuelle Ergebnisse der repräsentativen Langzeitstudie. Media-Perspektiven 2020, 2020, 390–409. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Initiative D21 e. V. D21 DIGITAL INDEX 19/20 Jährliches Lagebild zur Digitalen Gesellschaft. 2020. Available online: https://initiatived21.de/publikationen/d21-digital-index-2019-2020/ (accessed on 24 October 2020). (In German).

- Hambrock, U. Die Suche nach Gesundheitsinformationen: Perspektiven und Marktüberblick. Bertelsmann Stiftung 2018, 9. (In German) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge (BAMF). Aktuelle Zahlen. Ausgabe:Juli 2020; Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge (BAMF): Nürnberg, Germany, 2020. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, E.A.; Butler, K.; Roche, T.; Cumming, J.; Taknint, J.T. Refugee youth: A review of mental health counselling issues and practices. Can. Psychol. Can. 2016, 57, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorm, A.F.; E Korten, A.; A Jacomb, P.; Christensen, H.; Rodgers, B.; Pollitt, P. “Mental health literacy”: A survey of the public’s ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Med. J. Aust. 1997, 166, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorm, A.F. Why We Need the Concept of “Mental Health Literacy”. Health Commun. 2015, 30, 1166–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorm, A.F. Mental health literacy. Br. J. Psychiatry 2000, 177, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, D.L. Focus Groups. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1996, 22, 129–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, M.; Mack, B.; Renn, O. Fokusgruppen in der empirischen Sozialwissenschaft: Von der Konzeption bis zur Auswertung; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Pohontsch, N.J.; Müller, V.; Brandner, S.; Karlheim, C.; Jünger, S.; Klindtworth, K.; Stamer, M.; Höfling-Engels, N.; Kleineke, V.; Brandt, B.; et al. Gruppendiskussionen in der Versorgungsforschung—Teil 1: Einführung und Überlegungen zur Methodenwahl und Planung. Gesundheitswesen 2018, 80, 864–870. (In German) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xyländer, M.; Kleineke, V.; Jünger, S.; Klindtworth, K.; Karlheim, C.; Steffen, H.; Müller, V.; Höfling-Engels, N.; Patzelt, C.; Stamer, M.; et al. Gruppendiskussionen in der Versorgungsforschung—Teil 2: Überlegungen zum Begriff der Gruppe, zur Moderation und Auswertung von Gruppendiskussionen sowie zur Methode der Online-Gruppendiskussion. Gesundheitswesen 2020, 82, 998–1007. (In German) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, K.; Branigan, P. Using focus groups to evaluate health promotion interventions. Health Educ. 2000, 100, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colucci, E. On the Use of Focus Groups in Cross-Cultural Research. In Doing Cross-Cultural Research; Liamputtong, P., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; Volume 34, pp. 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Namey, E.; McKenna, K. How Many Focus Groups Are Enough? Building an Evidence Base for Nonprobability Sample Sizes. Field Methods 2017, 29, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research, 4th ed.; Aldine: New Brunswick, NB, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Leask, J.; Hawe, P.; Chapman, S. Focus group composition: A comparison between natural and constructed groups. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2001, 25, 152–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rädiker, S.; Kuckartz, U. Analyse Qualitativer Daten mit MAXQDA; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- VERBI GmbH. Qualitative Datenanalyse mit MAXQDA; Software für Windows & macOS; VERBI GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckartz, U. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Methoden, Praxis, Computerunterstützung, 4th ed.; Beltz Juventa: Weinheim, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.; Demler, O.; Jin, R.; Merikangas, K.R.; Walters, E.E. Lifetime Prevalence and Age-of-Onset Distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, M.; Bock, T.; Naber, D.; Löwe, B.; Schulte-Markwort, M.; Schäfer, I.; Gumz, A.; Degkwitz, P.; Schulte, B.; König, H.; et al. Die psychische Gesundheit von Kindern, Jugendlichen und jungen Erwachsenen—Teil 1: Häufigkeit, Störungspersistenz, Belastungsfaktoren, Service-Inanspruchnahme und Behandlungsverzögerung mit Konsequenzen. Fortschr. Neurol Psychiatr. 2013, 81, 614–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waqas, A.; Malik, S.; Fida, A.; Abbas, N.; Mian, N.; Miryala, S.; Amray, A.N.; Shah, Z. and Naveed, S. Interventions to Reduce Stigma Related to Mental Illnesses in Educational Institutes: A Systematic Review. Psychiatr. Q. 2020, 91, 887–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulliver, A.; Griffiths, K.M.; Christensen, H. Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2010, 10, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitchener, B.A.; Jorm, A.F. Mental Health First aid Training: Review of Evaluation Studies. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2006, 40, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altweck, L.; Marshall, T.C.; Ferenczi, N.; Lefringhausen, K. Mental health literacy: A cross-cultural approach to knowledge and beliefs about depression, schizophrenia and generalized anxiety disorder. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, M.E.; Ravid, A.; Gibb, B.; George-Denn, D.; Bronstein, L.R.; McLeod, S. Adolescent Mental Health Literacy: Young People’s Knowledge of Depression and Social Anxiety Disorder. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 58, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, K.S.; Jorm, A.F.; Kitchener, B.A.; Reavley, N.J. Mental health first aid training for Australian medical and nursing students: An evaluation study. BMC Psychol. 2015, 3, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eack, S.M.; Newhill, C.E.; Watson, A.C. Effects of Severe Mental Illness Education on MSW Student Attitudes about Schizophrenia. J. Soc. Work Educ. 2012, 48, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, L.T. Mental health literacy and mental health status in adolescents: A population-based survey. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2014, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, I.; Lund, C.; Stein, D.J. Optimizing mental health services in low-income and middle-income countries. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2011, 24, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petschel, A.; Will, A.-K. Migrationshintergrund—Ein Begriff, viele Definitionen. Ein Überblick auf Basis des Mikrozensus 2018; Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis): Wiesbaden, Germany, 2018. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- El-Mafaalani, A. Diskriminierung von Menschen mit Migrationshintergrund. In Handbuch Diskriminierung; Scherr, A., El-Mafaalani, A., Gökcen, Y.E., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien: Wiesbaden, Germamy, 2016; pp. 1–14, (In German). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.G.; Gorukanti, A.L.; Jurkunas, L.M.; Handley, M.A. The Health Literacy of U.S. Immigrant Adolescents: A Neglected Research Priority in a Changing World. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horn, A.; Vogt, D.; Messer, M.; Schaeffer, D. Health Literacy von Menschen mit Migrationshintergrund in der Patientenberatung stärken. Bundesgesundheitsblatt-Gesundheitsforschung-Gesundheitsschutz 2015, 58, 577–583. (In German) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beutel, M.E.; Jünger, C.; Klein, E.M.; Wild, P.S.; Lackner, K.J.; Blettner, M.; Banerjee, M.; Michal, M.; Wiltink, J.; Brähler, E. Depression, anxiety and suicidal ideation among 1st and 2nd generation migrants—Results from the Gutenberg health study. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reich, H.; Bockel, L.; Mewes, R. Motivation for Psychotherapy and Illness Beliefs in Turkish Immigrant Inpatients in Germany: Results of a Cultural Comparison Study. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2015, 2, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laabdallaoui, M.; Rüschoff, S.I. Umgang mit muslimischen Patienten, 2nd ed.; Psychiatrie Verlag: Koln, Germany, 2017. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Elsdörfer, U. Medizin, Psychologie und Beratung im Islam: Historische, Tiefenpsychologische und Systemische Annäherungen; Helmer: Königstein/Taunus, Germany, 2007. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Hausotter, W.; Schouler-Ocak, M. Begutachtung bei Menschen mit Migrationshintergrund; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Urban & Fischer: Munchen, Germany, 2013. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Gün, A.K. Interkulturelle therapeutische Kompetenz: Möglichkeiten und Grenzen Psychotherapeutischen Handelns, 1st ed.; Verlag W. Kohlhammer: Stuttgart, Germany, 2018. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Rohde, P.; Lewinsohn, P.M.; Klein, D.N.; Seeley, J.R.; Gau, J.M. Key Characteristics of Major Depressive Disorder Occurring in Childhood, Adolescence, Emerging Adulthood, and Adulthood. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 1, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ubaidi, B.A. Gender Relationship with Depressive Disorder. J. Community Prev. Med. 2018, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.A.; Gardner, C.O.; Prescott, C.A.; Kendler, K.S. Gender Differences in the Symptoms of Major Depression in Opposite-Sex Dizygotic Twin Pairs. AJP 2002, 159, 1427–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.J.; Koch, E. Gender Differences in Stressors Related to Migration and Acculturation in Patients with Psychiatric Disorders and Turkish Migration Background. J. Immigr. Minority Health 2017, 19, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morawa, E.; Erim, Y. Acculturation and Depressive Symptoms among Turkish Immigrants in Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 9503–9521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesinos, A.H.; Rapp, M.; Temur-Erman, S.; Heinz, A.; Hegerl, U.; Schouler-Ocak, M. The influence of stigma on depression, overall psychological distress, and somatization among female Turkish migrants. Eur. Psychiatry 2012, 27, S22–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadaczynski, K.; Okan, O.; Messer, M.; Rathmann, K. Digitale Gesundheitskompetenz von Studierenden in Deutschland. Ergebnisse einer bundesweiten Online-Befragung; HS Fulda und Universität Bielefeld: Bielefeld, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, E.A.; Begoray, D.L. Mental health literacy for refugee youth: A cultural approach. In International Handbook of Health Literacy: Research, Practice and Policy across the Life-Span; Okan, O., Bauer, U., Levin-Zamir, D., Pinheiro, P., Sørensen, K., Eds.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lühnen, J.; Albrecht, M.; Hanßen, K.; Hildebrandt, J.; Steckelberg, A. Leitlinie evidenzbasierte Gesundheitsinformation: Einblick in die Methodik der Entwicklung und Implementierung. Z. Evidenz Fortbild. Qual. Gesundh. 2015, 109, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reifegerste, D.; Baumann, E. Medien und Gesundheit; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, U. The social embeddedness of health literacy. In International Handbook of Health Literacy: Research, Practice and Policy across the Life-Span; Okan, O., Bauer, U., Levin-Zamir, D., Pinheiro, P., Sørensen, K., Eds.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Reifegerste, D.; Ort, A. Gesundheitskommunikation, 1st ed.; Nomos: Baden-Baden, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jorm, A.F. Mental health literacy interventions in adults. In International Handbook of Health Literacy: Research, Practice and Policy across the Life-Span; Okan, O., Bauer, U., Levin-Zamir, D., Pinheiro, P., Sørensen, K., Eds.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Levin-Zamir, D.; Bertschi, I. Media health literacy, eHealth literacy and health behavior across the lifespan: Current progress and future challenges. In International Handbook of Health Literacy: Research, Practice and Policy across the Life-Span; Okan, O., Bauer, U., Levin-Zamir, D., Pinheiro, P., Sørensen, K., Eds.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Döring, N. Gesundheitskommunikation auf YouTube: Aktueller Forschungsstand. In Digitale Gesundheitskommunikation: Zwischen Meinungsbildung und Manipulation, 1st Auflage; Scherenberg, V., Pundt, J., Lohmann, H., Opaschowski, H., Eds.; Apollon University Press: Bremen, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Furnham, A.; Hamid, A. Mental health literacy in non-western countries: A review of the recent literature. Mental Health Rev. J. 2014, 19, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammarberg, K.; Kirkman, M.; de Lacey, S. Qualitative research methods: When to use them and how to judge them. Hum. Reprod. 2016, 31, 498–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gender | Male (n) | Female (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ≤14 | / | 1 |

| 15–19 | 2 | 8 | |

| 20–24 | 17 | 19 | |

| 25–29 | 5 | 15 | |

| ≥30 | 1 | / | |

| Migrant background | migrant background | 13 | 27 |

| no migrant background | 12 | 16 | |

| Total | 25 | 43 | |

| Main Categories | Subcategories |

|---|---|

| (Mental health) challenges in everyday life | Experience and dealing with psychological problems |

| Level of knowledge and attitudes towards mental health/illness | |

| Health care situation | |

| Reasons/Triggers for psychological problems | |

| Psychological symptoms/disorders | |

| Gender aspects | |

| Health Literacy Components | Access Health Informations |

| Understand Health Informations | |

| Appraise Health Informations | |

| Apply Health Informations | |

| Digital media in everyday life | User interface/application purpose of end devices |

| Types of media | |

| Duration of media use | |

| Reasons for media use | |

| Quality features | |

| Positive aspects of media | |

| Negative aspects of media | |

| Transmission of health information (formats) | Communication types |

| (Online-) Formats | |

| Used (foreign) language | |

| Requirements for the planned website (of the project) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seven, Ü.S.; Stoll, M.; Dubbert, D.; Kohls, C.; Werner, P.; Kalbe, E. Perception, Attitudes, and Experiences Regarding Mental Health Problems and Web Based Mental Health Information Amongst Young People with and without Migration Background in Germany. A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010081

Seven ÜS, Stoll M, Dubbert D, Kohls C, Werner P, Kalbe E. Perception, Attitudes, and Experiences Regarding Mental Health Problems and Web Based Mental Health Information Amongst Young People with and without Migration Background in Germany. A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(1):81. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010081

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeven, Ümran Sema, Mendy Stoll, Dennis Dubbert, Christian Kohls, Petra Werner, and Elke Kalbe. 2021. "Perception, Attitudes, and Experiences Regarding Mental Health Problems and Web Based Mental Health Information Amongst Young People with and without Migration Background in Germany. A Qualitative Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 1: 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010081

APA StyleSeven, Ü. S., Stoll, M., Dubbert, D., Kohls, C., Werner, P., & Kalbe, E. (2021). Perception, Attitudes, and Experiences Regarding Mental Health Problems and Web Based Mental Health Information Amongst Young People with and without Migration Background in Germany. A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(1), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010081