Inculcation of Green Behavior in Employees: A Multilevel Moderated Mediation Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

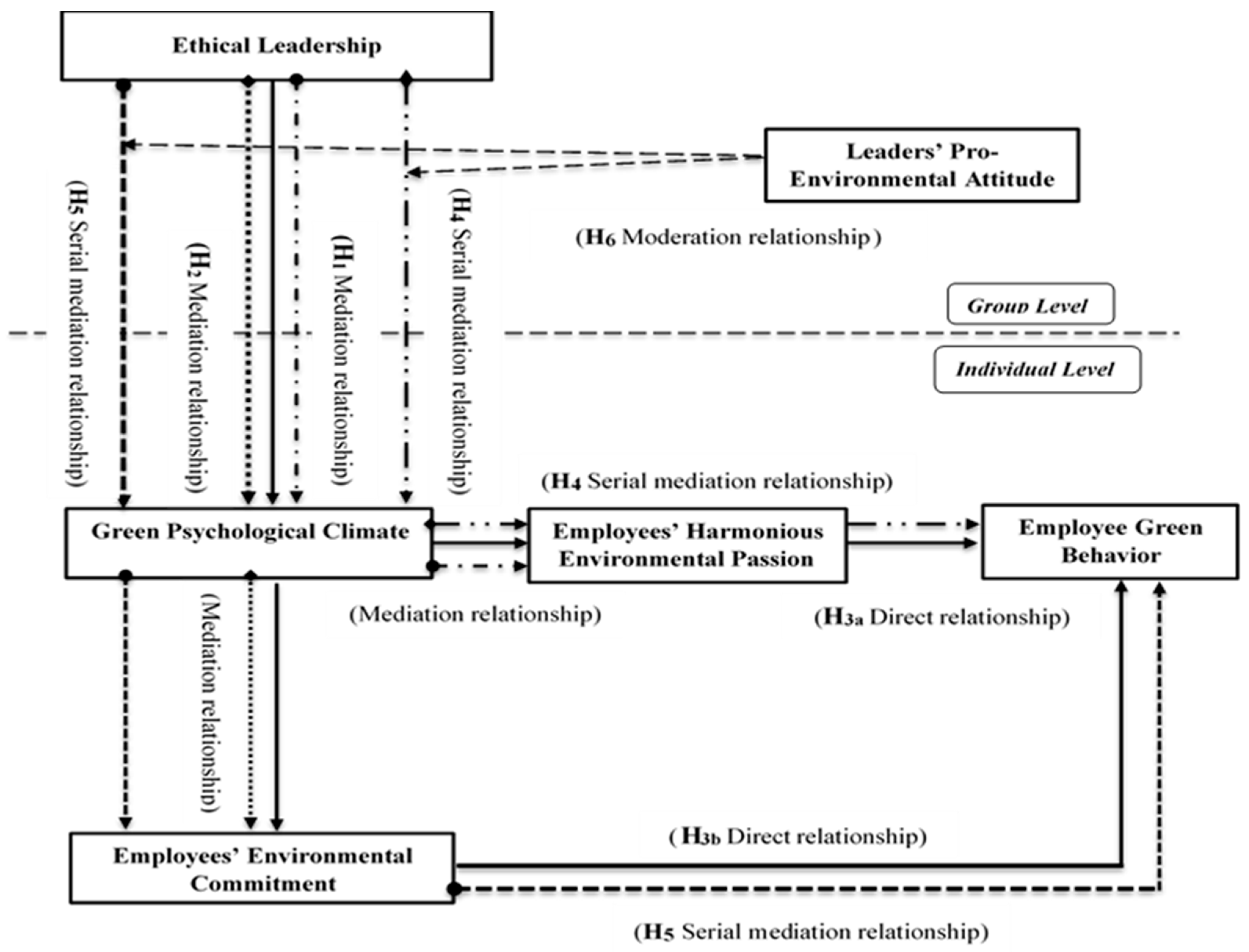

2. Hypotheses Development

2.1. Social Learning Theory

2.2. Mediation of a Green Psychological Climate on the Relationship of Ethical Leadership and Employees’ Harmonious Environmental Passion

2.3. Mediation of a Green Psychological Climate on Ethical Leadership and Employees’ Environmental Commitment Relationship

2.4. Employees’ Harmonious Environmental Passion, Environmental Commitment and Green Behavior

2.5. Serial Mediation of a Green Psychological Climate and Employees’ Harmonious Environmental Passion on the Indirect Effect of Ethical Leadership on Employee Green Behavior

2.6. Serial Mediation of a Green Psychological Climate and Employees’ Environmental Commitment on the Indirect Effect of Ethical Leadership on Employee Green Behavior

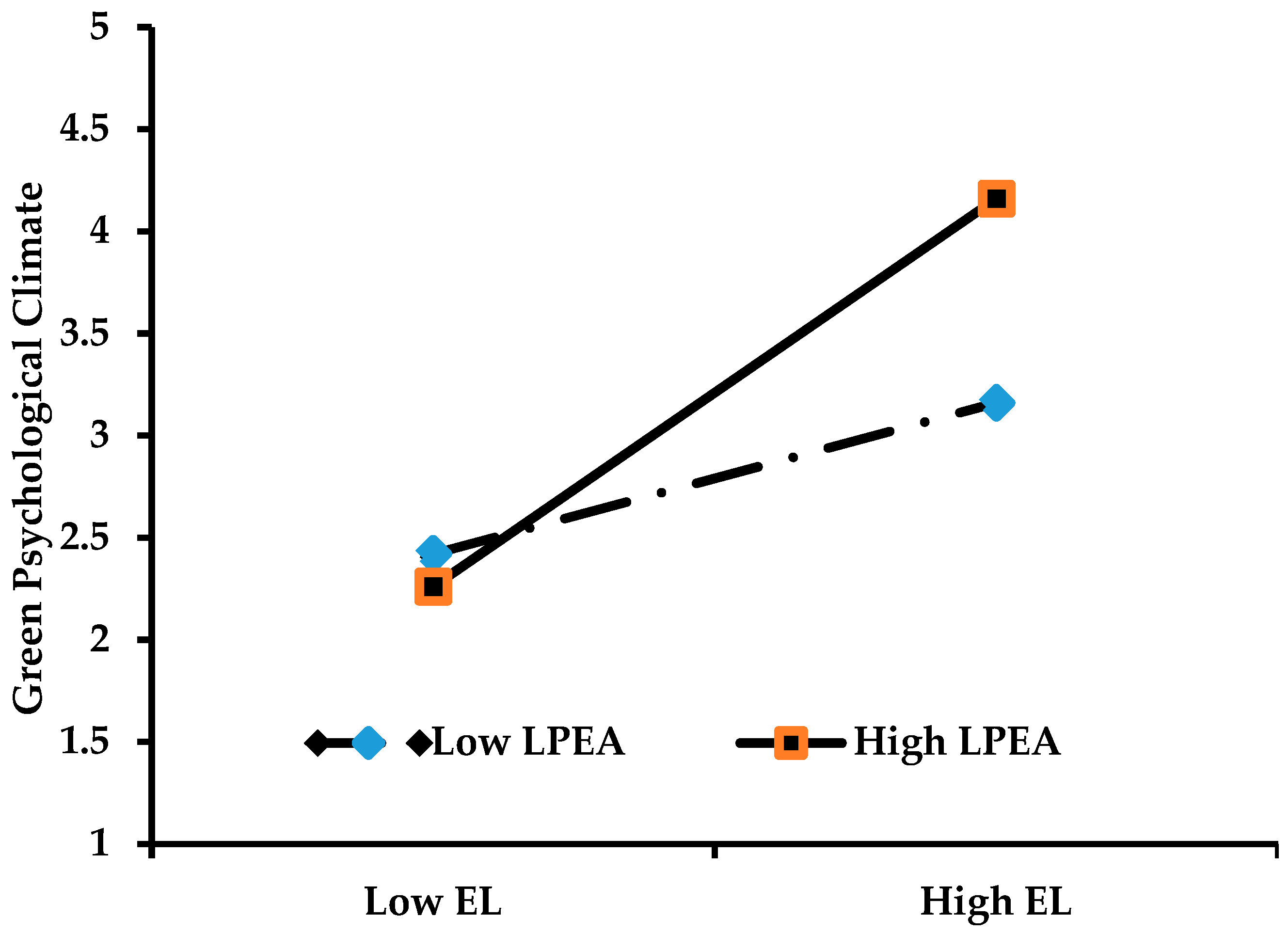

2.7. Moderation of Leaders’ Pro-Environmental Attitudes

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Sampling Strategy

3.2. Measures

3.3. Analysis Strategy

4. Data Analysis and Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Research Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gerland, P.; Raftery, A.E.; Ševčíková, H.; Li, N.; Gu, D.; Spoorenberg, T.; Alkema, L.; Fosdick, B.K.; Chunn, J.; Lalic, N.; et al. World population stabilization unlikely this century. Science 2014, 346, 234–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radić, V.; Hock, R. Regionally differentiated contribution of mountain glaciers and ice caps to future sea-level rise. Nat. Geosci. 2011, 4, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal-Millán, A.; Peris-Ortiz, M.; Leal-Rodríguez, A.L. The route towards sustainable innovation and entrepreneurship: An overview. In Sustainability in Innovation and Entrepreneurship; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Climate Change, the Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014.

- Hart, S.L.; Dowell, G. A natural-resource-based view of the firm: Fifteen years after. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1464–1479. [Google Scholar]

- WCED. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Bonan, G.B. Forests and climate change: Forcings, feedbacks, and the climate benefit of forests. Science 2008, 320, 1444–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladwin, T.N.; Kennelly, J.J.; Krause, T.S. Shifting paradigms for sustainable development: Implications for management theory and research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 874–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnenluecke, M.K.; Griffiths, A.; Mumby, P.J. Executives’ engagement with climate science and perceived need for business adaptation to climate change. Clim. Chang. 2015, 131, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairfield, K.D.; Harmon, J.; Behson, S.J. Influences on the organizational implementation of sustainability: An integrative model. Organ. Manag. J. 2011, 8, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.E. Portrait of a Slow Revolution Toward Environmental Sustainability. In Managing Human Resources for Environmental Sustainability; Jackson, S.E., Ones, D.S., Dilchert, S., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Rondinelli, D.; Vastag, G. Panacea, common sense, or just a label? The value of ISO 14001 environmental management systems. Eur. Manag. J. 2000, 18, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouldson, A.; Sullivan, R. Corporate environmentalism: Tracing the links between policies and performance using corporate reports and public registers. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2007, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.; McIntosh, M. Changing organizational culture for sustainability. In The Handbook of Organizational Culture and Climate; Ashkanasy, N.M., Wilderom, C.E.P., Peterson, M.F., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zibarras, L.D.; Coan, P. HRM practices used to promote pro-environmental behavior. Int. J. Hum. Resour. 2015, 26, 2121–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schramm, J. Advancing Sustainability: HR’s Role. Soc. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 7, 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Safari, A.; Salehzadeh, R.; Panahi, R.; Abolghasemian, S. multiple pathways linking environmental knowledge and awareness to employees’ green behavior. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2018, 18, 81–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Badir, Y. Workplace spirituality, perceived organizational support and innovative work behavior. J. Workplace Learn. 2017, 29, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, B.B.; Afsar, B.; Hafeez, S.; Khan, I.; Tahir, M.; Afridi, M.A. Promoting employee’s pro-environmental behavior through green human resource management practices. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2019, 26, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, S.; Afsar, B.; Al-Ghazali, B.M.; Maqsoom, A. How employee’s perceived corporate social responsibility affects employee’s pro-environmental behaviour? The influence of organizational identification, corporate entrepreneurship, and environmental consciousness. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2020, 27, 616–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.A.; Zacher, H.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Pro-environmental organizational culture and climate. In The Psychology of Green Organizations; Robertson, J.L., Barling, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 322–348. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, J.L.; Barling, J. Greening organizations through leaders’ influence on employees’ pro-environmental behaviors. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 176–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, C.; Ma, J.; Bartnik, R.; Haney, M.H.; Kang, M. Ethical leadership: An integrative review and future research agenda. Ethics Behav. 2018, 28, 104–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, L.M.; Sarkis, J. The role of employees’ leadership perceptions, values, and motivation in employees’ proenvironmental behaviors. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 205, 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kalshoven, K.; Den Hartog, D.N.; De Hoogh, A.H. Ethical leadership at work questionnaire (ELW). Lead. Q. 2011, 22, 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoch, J.E.; Bommer, W.H.; Dulebohn, J.H.; Wu, D. Do ethical, authentic, and servant leadership explain variance above and beyond transformational leadership? A meta-analysis. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 501–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenleaf, R.K.; Frick, D.M.; Spears, L.C. On Becoming a Servant-Leader; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Haque, A.; Fernando, M.; Caputi, P. The relationship between responsible leadership and organisational commitment and the mediating effect of employee turnover intentions: An empirical study with Australian employees. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 156, 759–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, D.M.; Kuenzi, M.; Greenbaum, R.; Bardes, M.; Salvador, R.B. How low does ethical leadership flow? Test of a trickle-down model. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2008, 108, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K.; Harrison, D.A. Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2005, 97, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K. Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. Leadersh. Q. 2006, 17, 595–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action; Prentice–Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, D.M.; Aquino, K.; Greenbaum, R.L.; Kuenzi, M. Who displays ethical leadership, and why does it matter? An examination of antecedents and consequences of ethical leadership. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Hartnell, C.A.; Misati, E. Does ethical leadership enhance group learning behavior? Examining the mediating influence of group ethical conduct, justice climate, and peer justice. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 72, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.A.; Zacher, H.; Ashkanasy, N.M. On the importance of pro-environmental organizational climate for EGB. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2012, 5, 497–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, L.R.; Choi, C.C.; Ko, C.-H.E.; McNeil, P.K.; Minton, M.K.; Wright, M.A.; Kim, K.-I. Organizational and psychological climate: A review of theory and research. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2008, 17, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirtas, O.; Akdogan, A.A. The effect of ethical leadership behavior on ethical climate, turnover intention, and affective commitment. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 130, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, G.; Albanesi, C.; Pietrantoni, L. The interplay among environmental attitudes, pro-environmental behavior, social identity, and pro-environmental institutional climate. A longitudinal study. Environ. Educ. Res. 2017, 23, 176–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Starik, M. Taoist leadership and employee green behaviour: A cultural and philosophical micro foundation of sustainability. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 1302–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, H.H. Mental models and transformative learning: The key to leadership development? Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2008, 19, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Lin, L.; Liu, J.T. Leveraging the employee voice: A multi-level social learning perspective of ethical leadership. Int. J. Hum. Resour. 2019, 30, 1869–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grojean, M.W.; Resick, C.J.; Dickson, M.W.; Smith, D.B. Leaders, values, and organizational climate: Examining leadership strategies for establishing an organizational climate regarding ethics. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 55, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryati, A.S.; Sudiro, A.; Hadiwidjaja, D.; Noermijati, N. The influence of EL to deviant workplace behavior mediated by ethical climate and organizational commitment. Int. J. Law Manag. 2018, 60, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O.; Paillé, P.; Raineri, N. The nature of employees’ pro-environmental behaviors. In The Psychology of Green Organizations; Robertson, J.L., Barling, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 12–32. [Google Scholar]

- Cantor, D.E.; Morrow, P.C.; Montabon, F. Engagement in environmental behaviors among supply chain management employees: An organizational support theoretical perspective. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2012, 48, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, O.; Amichai-Hamburger, Y.; Shterental, T. The dynamic of corporate self-regulation: ISO 14001, environmental commitment, and organizational citizenship behavior. Law Soc. Rev. 2009, 43, 593–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raineri, N.; Paillé, P. Linking corporate policy and supervisory support with environmental citizenship behaviors: The role of employee environmental beliefs and commitment. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 137, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M. Leadership, Psychology, and Organizational Behavior; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Ones, D.S.; Dilchert, S. Environmental sustainability at work: A call to action. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2012, 5, 444–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ones, D.S.; Dilchert, S. Employee green behaviors. In Managing Human Resources for Environmental Sustainability; Jackson, S.E., Ones, D.S., Dilchert, S., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 85–116. [Google Scholar]

- Priyankara, H.P.R.; Luo, F.; Saeed, A.; Nubuor, S.A.; Jayasuriya, M.P.F. How does leader’s support for environment promote organizational citizenship behaviour for environment? A multi-theory perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Mejía-Morelos, J.H. Antecedents of pro-environmental behaviours at work: The moderating influence of psychological contract breach. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.L.; Carleton, E. Uncovering how and when environmental leadership affects employees’ voluntary pro-environmental behavior. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2018, 25, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littleford, C.; Ryley, T.J.; Firth, S.K. Context, control and the spillover of energy use behaviours between office and home settings. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawcroft, L.J.; Milfont, T.L. The use (and abuse) of the new environmental paradigm scale over the last 30 years: A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Möser, G. Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordano, M.; Frieze, I.H. Pollution reduction preferences of US environmental managers: Applying Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 627–641. [Google Scholar]

- Cordano, M.; Marshall, R.S.; Silverman, M. How do small and medium enterprises go “green”? A study of environmental management programs in the US wine industry. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 92, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissing-Olson, M.J.; Iyer, A.; Fielding, K.S.; Zacher, H. Relationships between daily affect and pro-environmental behavior at work: The moderating role of pro-environmental attitude. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 156–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, L.M.; Sarkis, J.; Zhu, Q. How transformational leadership and employee motivation combine to predict employee proenvironmental behaviors in China. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 35, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuriev, A.; Boiral, O.; Francoeur, V.; Paillé, P. Overcoming the barriers to pro-environmental behaviors in the workplace: A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Boiral, O. Pro-environmental behavior at work: Construct validity and determinants. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 36, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Arain, G.A.; Bukhari, S.; Khan, A.K.; Hameed, I. The impact of abusive supervision on employees’ feedback avoidance and subsequent help-seeking behaviour: A moderated mediation model. J. Manag. Organ. 2018, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arain, G.A.; Sheikh, A.; Hameed, I.; Asadullah, M.A. Do as I do: The effect of teachers’ EL on business students’ academic citizenship behaviors. Ethics Behav. 2017, 27, 665–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofori, G. Ethical leadership: Examining the relationships with full range leadership model, employee outcomes, and organizational culture. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 90, 533–547. [Google Scholar]

- Pasricha, P.; Rao, M.K. The effect of ethical leadership on employee social innovation tendency in social enterprises: Mediating role of perceived social capital. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2018, 27, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D.; Mertig, A.G.; Jones, R.E. Measuring endorsement of the New Ecological Paradigm: A revised NEP scale. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, J. The relationship between pro-environmental attitude and employee green behavior: The role of motivational states and green work climate perceptions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 7341–7352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.A.; Zacher, H.; Parker, S.L.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Bridging the gap between green behavioral intentions and EGB: The role of GPC. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 996–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.S.; Ali, M.; Usman, M.; Saleem, S.; Jianguo, D. Interrelationships between ethical leadership, GPC, and organizational environmental citizenship behavior: The moderating role of gender. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Badir, Y.; Kiani, U.S. Linking spiritual leadership and employee pro-environmental behavior: The influence of workplace spirituality, intrinsic motivation, and environmental passion. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Valéau, P. “I don’t owe you, but i am committed”: Does felt obligation matter on the effect of green training on employee environmental commitment? Organ. Environ. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, D. Functional relations among constructs in the same content domain at different levels of analysis: A typology of composition models. J. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 83, 234–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farh, C.I.; Chen, Z. Beyond the individual victim: Multi-level consequences of abusive supervision in teams. J. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 99, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preacher, K.J.; Zhang, Z.; Zyphur, M.J. Alternative methods for assessing mediation in multi-level data: The advantages of multi-level SEM. Struct. Equ. Modeling 2011, 18, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Kim, Y.; Han, K.; Jackson, S.E.; Ployhart, R.E. Multilevel influences on voluntary workplace green behavior: Individual differences, leader behavior, and coworker advocacy. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1335–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, F.; Qadeer, F.; Abbas, Z.; Hussain, I.; Saleem, M.; Hussain, A.; Aman, J. Corporate social responsibility and employees’ negative behaviors under abusive supervision: A multi-level insight. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.; Qadeer, F.; Mahmood, F.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Han, H. Ethical leadership and employee green behavior: A multi-level moderated mediation analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, F.; Qadeer, F.; Sattar, U.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Saleem, M.; Aman, J. Corporate social responsibility and firms’ financial performance: A new insight. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, H.H. Modern Factor Analysis; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakata, C.; Zhu, Z.; Kraimer, M.L.C. The complex contribution of information technology capability to business performance. J. Manag. Issues 2008, 20, 485–506. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th international ed.; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H.; Zou, J.; Chen, H.; Long, R. Promotion or inhibition? Moral norms, anticipated emotion and employee’s pro-environmental behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuenzi, M.; Mayer, D.M.; Greenbaum, R.L. Creating an ethical organizational environment: The relationship between ethical leadership, ethical organizational climate, and unethical behavior. Pers. Psychol. 2020, 73, 43–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, J.; Shen, J.; Deng, X. Effects of green HRM practices on employee workplace green behavior: The role of psychological green climate and employee green values. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2017, 56, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhou, Q. Exploring the impact of responsible leadership on organizational citizenship behavior for the environment. Sustainability 2019, 11, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junsheng, H.; Masud, M.M.; Akhtar, R.; Rana, M. The Mediating Role of Employees’ Green Motivation between Exploratory Factors and Green Behaviour in the Malaysian Food Industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavik, Y.L.; Tang, P.M.; Shao, R.; Lam, L.W. Ethical leadership and employee knowledge sharing: Exploring dual-mediation paths. Leadersh. Q. 2018, 29, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Yang, C.; Bossink, B.A.; Fu, J. Linking leaders’ voluntary workplace green behavior and team green innovation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choong, Y.O.; Ng, L.P.; Tee, C.W.; Kuar, L.S.; Teoh, S.Y.; Chen, I.C. Green work climate and pro-environmental behaviour among academics: The mediating role of harmonious environmental passion. Int. J. Manag. 2020, 26, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Umrani, W.A. Corporate social responsibility and pro-environmental behavior at workplace: The role of moral reflectiveness, coworker advocacy, and environmental commitment. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2020, 27, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. New environmental theories: Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilms, W.W.; Hardcastle, A.J.; Zell, D.M. Cultural transformation at NUMMI. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 1994, 36, 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Das, A.K.; Biswas, S.R.; Jilani, A.K.; Muhammad, M.; Uddin, M.J.S. Corporate environmental strategy and voluntary environmental behavior—Mediating effect of psychological green climate. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Vandenberghe, C. Ethical leadership and team ethical voice and citizenship behavior in the military: The roles of team moral efficacy and ethical climate. Group Organ. Manag. 2020, 45, 514–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Items | Alpha | CR | AVE | MSV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethical Leadership | 10 | 0.96 | 0.81 | 0.57 | 0.32 |

| Green Psychological Climate | 5 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.50 | 0.29 |

| Employee Green Behavior | 13 | 0.83 | 0.72 | 0.59 | 0.43 |

| Employees’ Harmonious Environmental Passion | 10 | 0.90 | 0.70 | 0.60 | 0.51 |

| Employees’ Environmental Commitment | 8 | 0.83 | 0.91 | 0.63 | 0.41 |

| Leaders’ Pro-environmental Attitude | 15 | 0.70 | 0.83 | 0.54 | 0.37 |

| Variable | Mean | Range | SD | Ske | Kur | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. EL | 4.20 | 1–5 | 0.57 | −2.05 | 1.98 | 1 | ||||

| 2. GPC | 4.22 | 1–5 | 0.75 | −1.60 | 2.08 | 0.22 ** | 1 | |||

| 3. EGB | 3.09 | 0–4 | 0.52 | −1.31 | 1.38 | 0.35 ** | 0.39 ** | 1 | ||

| 4. EHEP | 4.01 | 1–5 | 0.56 | 2.00 | 2.02 | 0.16 ** | 0.55 ** | 0.63 ** | 1 | |

| 5. EEC | 4.37 | 1–6 | 0.51 | −0.97 | 0.53 | 0.40 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.57 ** | 0.37 ** | 1 |

| 6. LPEA | 4.33 | 1–5 | 0.24 | 0.37 | 0.70 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| Estimates | 95% CI | Remarks | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group → Individual | |||

| EL → GPC | 0.173 * | (0.040, 0.307) | |

| EL → EHEP | 0.155 * | (0.060, 0.250) | |

| EL → EEC | 0.062 | (−0.035, 0.160) | |

| EL → EGB | 0.151 * | (0.087, 0.215) | |

| Individual → Individual | |||

| GPC → EHEP | 0.504 ** | (0.453, 0.555) | |

| GPC → EEC | 0.308 ** | (0.234, 0.382) | |

| EHEP → EGB | 1.070 ** | (0.457, 1.683) | Supported (H3a) |

| EEC → EGB | 0.866 ** | (0.495, 1.237) | Supported (H3b) |

| Estimates | 95% CI | Remarks | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group → Individual → Individual | |||

| EL → GPC → EHEP | 0.087 * | (0.021, 0.154) | Supported (H1) |

| EL → GPC → EEC | 0.053 * | (0.011, 0.096) | Supported (H2) |

| Group → Individual → Individual → Individual | |||

| EL → GPC → EHEP → EGB | 0.093 * | (0.016, 0.170) | Supported (H4) |

| EL → GPC → EEC → EGB | 0.045 * | (0.009, 0.081) | Supported (H5) |

| Estimates | 95% CI | Remarks | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group * Group → Individual | |||

| EL * LPEA → GPC | 0.291 ** | (0.061, 0.522) | |

| Group * Group → Individual → Individual → Individual | |||

| EL * LPEA → GPC → EHEP → EGB | 0.157 ** | (0.072, 0.242) | Supported (H6a) |

| EL * LPEA → GPC → EEC → EGB | 0.077 * | (0.004, 0.150) | Supported (H6b) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saleem, M.; Qadeer, F.; Mahmood, F.; Han, H.; Giorgi, G.; Ariza-Montes, A. Inculcation of Green Behavior in Employees: A Multilevel Moderated Mediation Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 331. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010331

Saleem M, Qadeer F, Mahmood F, Han H, Giorgi G, Ariza-Montes A. Inculcation of Green Behavior in Employees: A Multilevel Moderated Mediation Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(1):331. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010331

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaleem, Maria, Faisal Qadeer, Faisal Mahmood, Heesup Han, Gabriele Giorgi, and Antonio Ariza-Montes. 2021. "Inculcation of Green Behavior in Employees: A Multilevel Moderated Mediation Approach" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 1: 331. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010331

APA StyleSaleem, M., Qadeer, F., Mahmood, F., Han, H., Giorgi, G., & Ariza-Montes, A. (2021). Inculcation of Green Behavior in Employees: A Multilevel Moderated Mediation Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(1), 331. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010331