Mental Health Inequities among Transgender People in Aotearoa New Zealand: Findings from the Counting Ourselves Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure

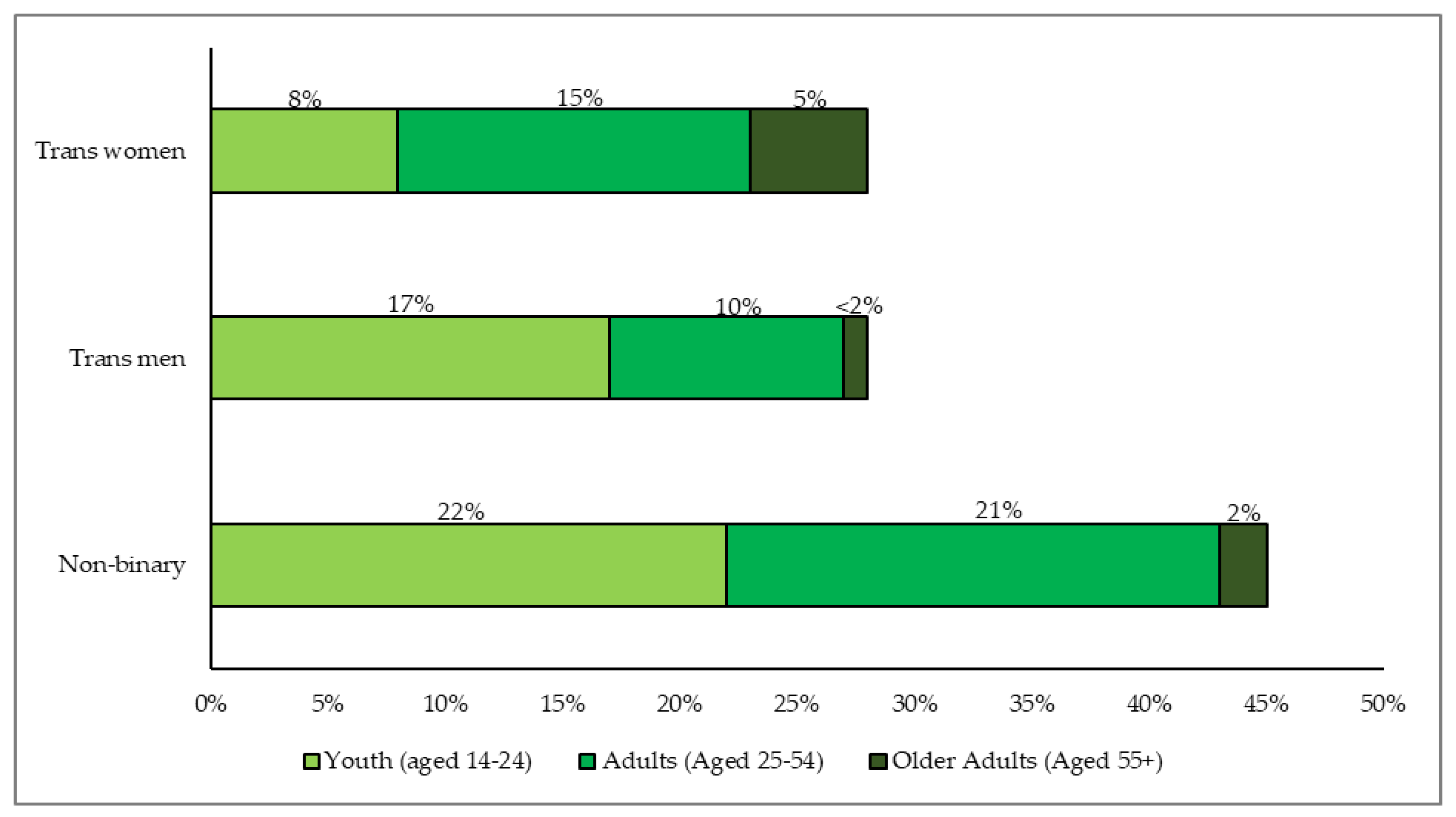

2.2. Participants

2.3. Population Comparisons

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Gender

2.4.2. Number of Years Living Full-Time in Affirmed Gender

2.4.3. Mental Health Diagnoses

2.4.4. Psychological Distress

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

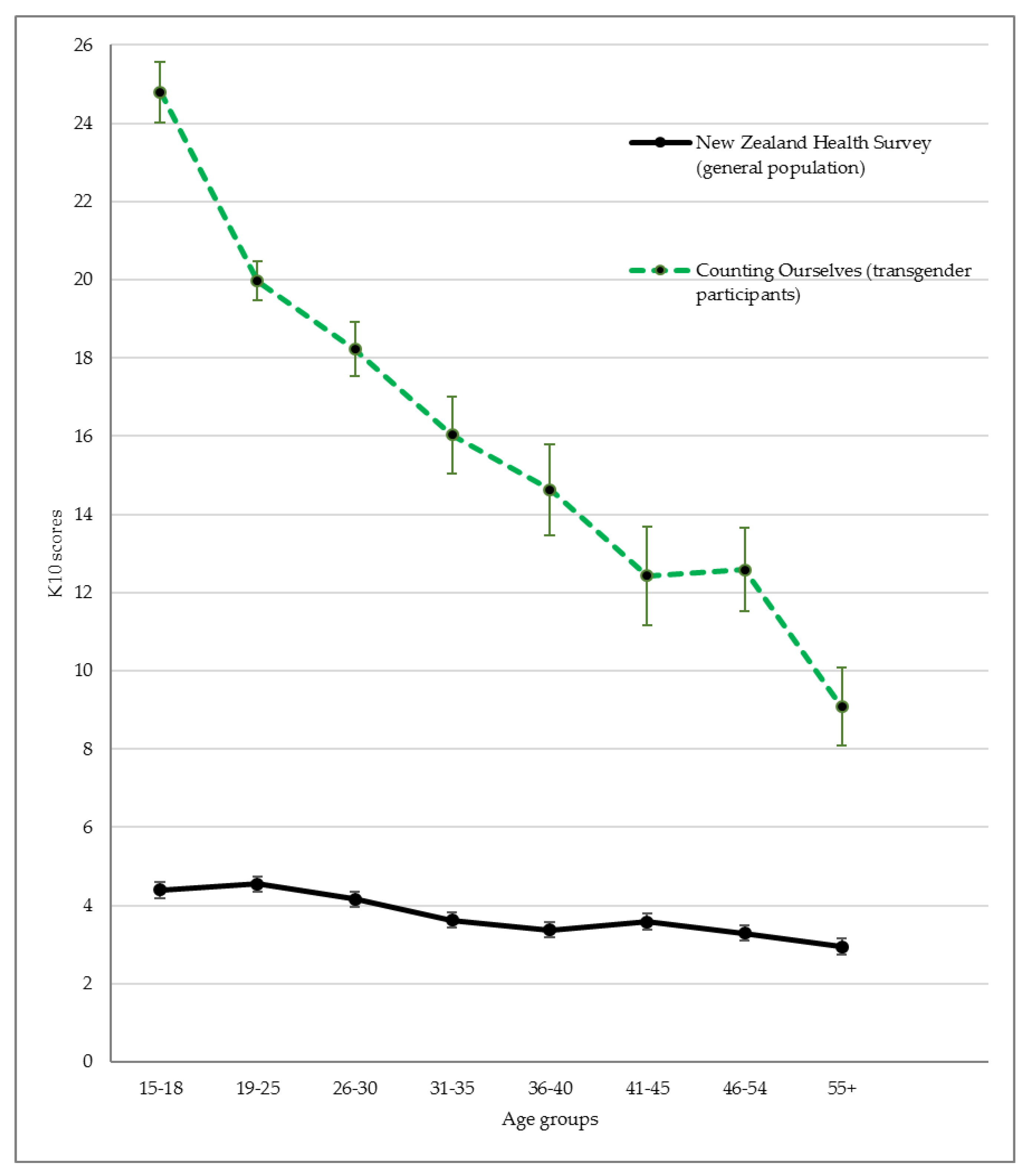

3.1. Mental Health Inequities

3.2. Age Group Differences

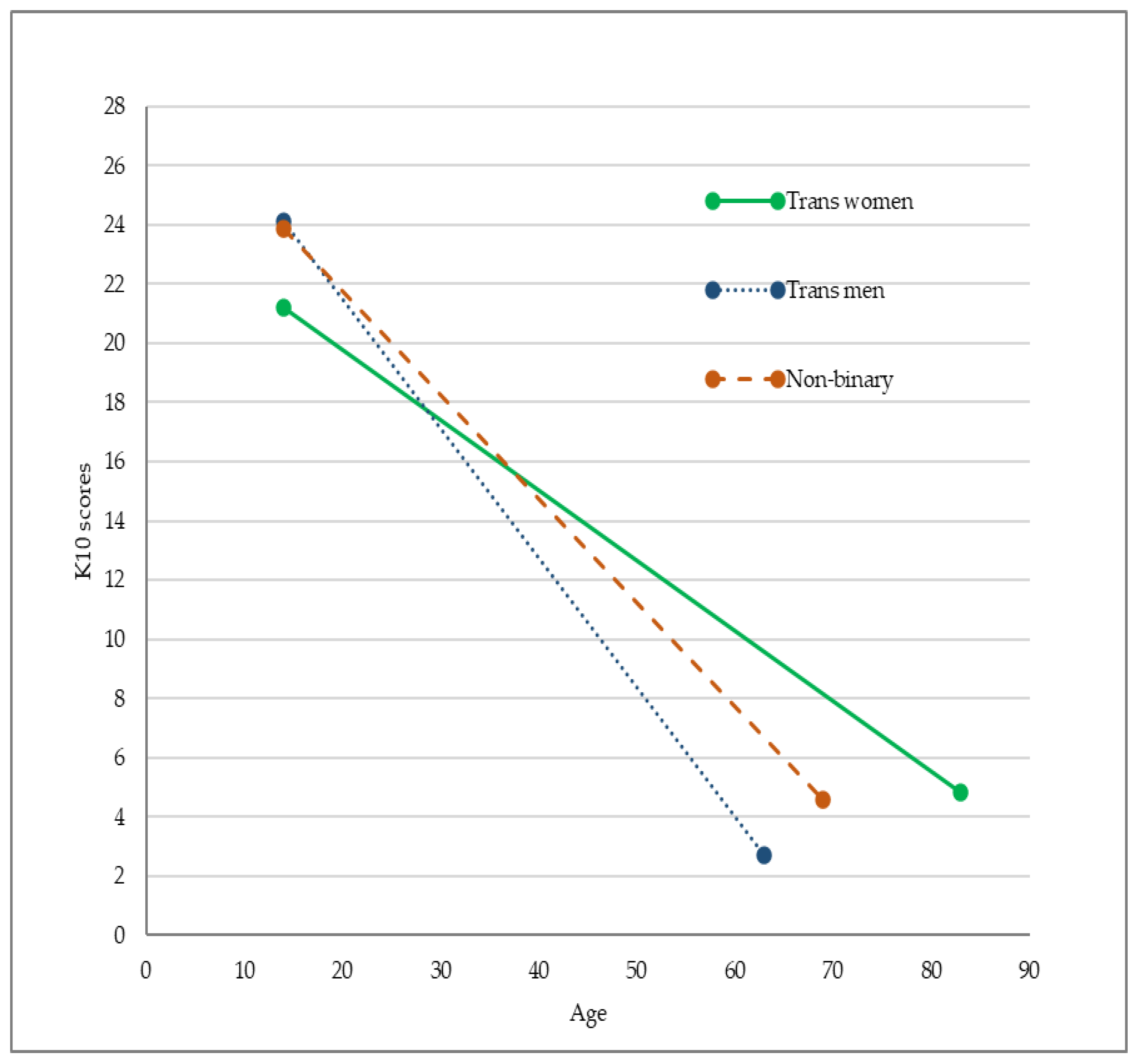

3.3. Gender and Age Differences

4. Discussion

4.1. Population-Based Comparisons

4.2. Age Comparisons

4.3. Gender Group Comparisons

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

7. Study Implications

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rimes, K.A.; Goodship, N.; Ussher, G.; Baker, D.; West, E. Non-binary and binary transgender youth: Comparison of mental health, self-harm, suicidality, substance use and victimization experiences. Int. J. Transgend. 2019, 20, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerekere, E. Part of the Whānau: The Emergence of Takatāpui Identity He Whāriki Takatāpui. Ph.D. Thesis, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, J.M. Translating transgender: Using western discourses to understand Samoan fa’afāfine. Sociol. Compass 2017, 11, e12485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crissman, H.P.; Stroumsa, D.; Kobernik, E.K.; Berger, M.B. Gender and frequent mental distress: Comparing transgender and non-transgender individuals’ self-rated mental health. J. Womens Health 2019, 28, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.A.; Bouman, W.P.; Haycraft, E.; Arcelus, J. Mental health and quality of life in non-binary transgender adults: A case control study. Int. J. Transgend. 2019, 20, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veale, J.F.; Watson, R.J.; Peter, T.; Saewyc, E.M. Mental health disparities among Canadian transgender youth. J. Adolesc. Health 2017, 60, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, S.E.; Herman, J.L.; Rankin, S.; Keisling, M.; Mottet, L.; Anafi, M. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey; National Center for Transgender Equality: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, B.D.L.; Socías, M.E.; Kerr, T.; Zalazar, V.; Sued, O.; Arístegui, I. Prevalence and correlates of lifetime suicide attempts among transgender persons in Argentina. J. Homosexual. 2016, 63, 955–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aparicio-García, M.E.; Díaz-Ramiro, E.M.; Rubio-Valdehita, S.; López-Núñez, M.I.; García-Nieto, I. Health and well-being of cisgender, transgender and non-binary young people. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, T.C.; Lucassen, M.F.G.; Bullen, P.; Denny, S.J.; Fleming, T.M.; Robinson, E.M.; Rossen, F.V. The health and well-being of transgender high school students: Results from the New Zealand Adolescent Health Survey (Youth’12). J. Adolesc. Health 2014, 55, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, Z.; Doherty, M.; Tilley, P.J.M.; McCaul, K.A.; Rooney, R.; Jancey, J. The First Australian Trans Mental Health Study: Summary of Results; School of Public Health, Curtin University: Perth, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R.; Zhu, X.; Wright, L.; Drescher, J.; Gao, Y.; Wu, L.; Ying, X.; Qi, J.; Chen, C.; Xi, Y.; et al. Suicidal ideation and attempted suicide amongst Chinese transgender persons: National population study. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 245, 1126–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, N.F.; Kenealy, T.W.; Connolly, M.J.; Mahony, F.; Barber, P.A.; Boyd, M.A.; Carswell, P.; Clinton, J.; Devlin, G.; Doughty, R.; et al. Health equity in the New Zealand health care system: A national survey. Int. J. Equity Health 2011, 10, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen, K.I.; Simoni, J.M.; Kim, H.-J.; Lehavot, K.; Walters, K.L.; Yang, J.; Hoy-Ellis, C.P.; Muraco, A. The health equity promotion model: Reconceptualization of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) health disparities. Am. J. Orthopsychiat. 2014, 84, 653–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riggs, D.W.; Ansara, G.Y.; Treharne, G.J. An evidence-based model for understanding the mental health experiences of transgender Australians. Aust. Psychol. 2015, 50, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.K.H.; Treharne, G.J.; Ellis, S.J.; Schmidt, J.M.; Veale, J.F. Gender minority stress: A critical review. J. Homosexual. 2019. Advanced online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testa, R.J.; Habarth, J.; Peta, J.; Balsam, K.; Bockting, W. Development of the gender minority stress and resilience measure. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2015, 2, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, I.H. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 674–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackman, K.B.; Dolezal, C.; Bockting, W.O. Generational differences in internalized transnegativity and psychological distress among feminine spectrum transgender people. LGBT Health 2018, 5, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattari, S.K.; Hasche, L. Differences across age groups in transgender and gender non-conforming people’s experiences of health care discrimination, harassment, and victimization. J. Aging Health 2016, 28, 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy-Ellis, C.P.; Fredriksen-Goldsen, K.I. Depression among transgender older adults: General and minority stress. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2017, 59, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisner, S.L.; Hughto, J.M.W. Comparing the health of non-binary and binary transgender adults in a statewide non-probability sample. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0221583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veale, J.F.; Byrne, J.L.; Tan, K.K.H.; Guy, S.; Yee, A.; Nopera, T.; Bentham, R. Counting Ourselves: The Health and Wellbeing of Trans and Non-Binary People in Aotearoa New Zealand; Transgender Health Research Lab, University of Waikato: Hamilton, New Zealand, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health. Methodology Report 2016/17: New Zealand Health Survey; Ministry of Health: Wellington, New Zealand, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R.C.; Barker, P.R.; Colpe, L.J.; Epstein, J.F.; Gfroerer, J.C.; Hiripi, E.; Howes, M.J.; Normand, S.-L.T.; Manderscheid, R.W.; Walters, E.E.; et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2003, 60, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley Browne, M.A.; Wells, J.E.; Scott, K.M.; McGee, M.A. The Kessler Psychological Distress Scale in Te Rau Hinengaro: The New Zealand Mental Health Survey. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2010, 44, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enders, C.K. Using the expectation maximization algorithm to estimate coefficient alpha for scales with item-level missing data. Psychol. Methods 2003, 8, 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bockting, W.; Miner, M.; Romine, R.; Hamilton, A.; Coleman, E. Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bariola, E.; Lyons, A.; Leonard, W.; Pitts, M.; Badcock, P.; Couch, M. Demographic and psychosocial factors associated with psychological distress and resilience among transgender individuals. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 2108–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, J.E.; Oakley Browne, M.A.; Scott, K.M.; McGee, M.A.; Baxter, J.; Kokaua, J. Prevalence, interference with life and severity of 12 month DSM-IV disorders in Te Rau Hinengaro: The New Zealand Mental Health Survey. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2006, 40, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, A.; Doyle, L.; Downes, C.; Murphy, R.; Sharek, D.; DeVries, J.; Begley, T.; McCann, E.; Sheerin, F.; Smyth, S. The LGBTIreland Report: National Study of the Mental Health and Wellbeing of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex People in Ireland; GLEN and BeLonG To: Dublin, Ireland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nuttbrock, L.; Bockting, W.; Rosenblum, A.; Mason, M.; Macri, M.; Becker, J. Gender identity conflict/affirmation and major depression across the life course of transgender women. Int. J. Transgender 2012, 13, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppink, J. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) vs. moderated regression (MODREG): Why the interaction matters. Health Prof. Educ. 2018, 4, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delahunt, J.W.; Denison, H.J.; Kennedy, J.; Hilton, J.; Young, H.; Chaudhri, O.B.; Elston, M.S. Specialist services for management of individuals identifying as transgender in New Zealand. N. Z. Med. J. 2016, 129, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Clunie, M. Rainbow Communities, Mental Health and Addiction: A Submission to the Government Inquiry Into Mental Health and Addiction—Oranga Tāngata, Oranga Whānau. Available online: www.mentalhealth.org.nz/assets/Our-Work/policy-advocacy/Rainbow-communities-and-mental-health-submission-to-the-Inquiry-into-Mental-Health-and-Addiction-08062018.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2020).

- Pega, F.; Veale, J.F. The case for the World Health Organization’s commission on social determinants of health to address gender identity. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.K.H.; Schmidt, J.M.; Ellis, S.J.; Veale, J.F. Mental health of trans and gender diverse people in Aotearoa/New Zealand: A review of the social determinants of inequities. N. Z. J. Psychol. 2019, 48, 64–72. [Google Scholar]

- The Yogyakarta Principles. The Yogyakarta Principles: Principles on the Application of International Human Rights Law in Relation to Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity. Available online: http://yogyakartaprinciples.org/principles-en/official-versions-pdf/ (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- PATHA. AusPATH and PATHA Welcome RACP Advice to Australian Minister Greg Hunt. Available online: https://patha.nz/News/8822288 (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- Kismodi, E.; Cabral, M.; Byrne, J.L. Transgender health care and human rights. In Principles of Transgender Medicine and Surgery, 2nd ed.; Ettner, R., Monstrey, S., Coleman, E., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Age Groups | Counting Ourselves | NZHS 2016/7 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | %/M (SD) | %/M (SD) | t-Test/Chi-Square Statistics | Effect Size | |

| Depression (Yes; No) | 854 | 65.7% | 16.7% | 49.45 ** | RR = 2.88 (2.47, 6.12) |

| 15−18 | 112 | 53.6% | 6.8% | 52.11 ** | RR = 7.71 (3.69, 16.12) |

| 19−25 | 288 | 71.5% | 14.7% | 64.85 ** | RR = 4.80 (2.96, 7.78) |

| 26−30 | 149 | 72.5% | 18.2% | 59.75 ** | RR = 4.06 (2.63, 6.27) |

| 31−35 | 75 | 69.3% | 15.4% | 59.85 ** | RR = 4.60 (2.83, 7.37) |

| 36−40 | 51 | 70.6% | 17.5% | 57.59 ** | RR = 3.94 (2.55, 6.10) |

| 41−45 | 43 | 62.8% | 19.3% | 40.02 ** | RR = 3.32 (2.15, 5.11) |

| 46−54 | 64 | 56.3% | 18.9% | 29.21 ** | RR = 2.95 (1.90, 4.58) |

| 55+ | 72 | 50.0% | 17.5% | 23.24 ** | RR = 2.78 (1.75, 4.41) |

| Anxiety (Yes; No) | 853 | 55.2% | 10.3% | 44.49 ** | RR = 5.50 (2.98, 10.16) |

| 15−18 | 117 | 53.8% | 5.4% | 57.72 ** | RR = 10.80 (4.51, 25.86) |

| 19−25 | 291 | 66.0% | 11.7% | 61.29 ** | RR = 5.50 (3.18, 9.52) |

| 26−30 | 149 | 58.4% | 12.6% | 44.22 ** | RR = 4.46 (2.62, 7.61) |

| 31−35 | 74 | 59.5% | 9.1% | 56.63 ** | RR = 6.67 (3.50, 12.69) |

| 36−40 | 47 | 55.3% | 10.7% | 43.78 ** | RR = 5.00 (2.79, 8.98) |

| 41−45 | 43 | 32.6% | 11.8% | 12.65 ** | RR = 2.75 (1.51, 5.01) |

| 46−54 | 60 | 40.0% | 11.3% | 22.13 ** | RR = 3.64 (1.98, 6.67) |

| 55+ | 72 | 29.2% | 9.4% | 13.00 ** | RR = 3.22 (1.61, 6.45) |

| K10 (0−40) | 886 | 17.86 (9.56) | 3.54 (5.12) | 83.11 ** | d = 1.87 (1.80, 1.93) |

| 15−18 | 124 | 24.80 (8.65) | 4.39 (5.31) | 42.78 ** | d = 2.84 (2.67, 3.02) |

| 19−25 | 298 | 19.96 (8.49) | 4.55 (5.96) | 44.61 ** | d = 2.10 (1.99, 2.22) |

| 26−30 | 152 | 18.22 (8.60) | 4.16 (5.93) | 29.22 ** | d = 1.90 (1.75, 2.06) |

| 31−35 | 75 | 16.03 (8.89) | 3.62 (5.05) | 21.26 ** | d = 1.72 (1.49, 1.94) |

| 36−40 | 53 | 14.63 (8.24) | 3.38 (4.93) | 16.60 ** | d = 1.66 (1.39, 1.93) |

| 41−45 | 46 | 12.43 (8.17) | 3.58 (5.24) | 11.46 ** | d = 1.29 (1.00, 1.58) |

| 46−54 | 64 | 12.58 (9.49) | 3.29 (4.88) | 15.22 ** | d = 1.23 (0.98, 1.48) |

| 55+ | 74 | 9.08 (7.57) | 2.95 (4.49) | 11.73 ** | d = 0.98 (0.76, 1.21) |

| Variables | Depression Diagnosis | Anxiety Diagnosis | K10 Psychological Distress | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age-adj Model | Age-adj Model | Age-adj Model | Age-int Model | |||||

| Wald Statistics | OR (95% CI) | Wald Statistics | OR (95% CI) | Wald Statistics | b (95% CI) | Wald Statistics | b (95% CI) | |

| Age | 0.82 | 1.00 (0.98, 1.01) | 15.18 ** | 0.98 (0.97, 0.99) | 189.20 ** | −0.31 (−0.35, −0.27) | 195.66 ** | −0.24 (−0.30, −0.18) |

| Gender | 7.76 * | 21.121 ** | 0.87 | 9.59 ** | ||||

| Trans women | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||||

| Trans men | 7.38 ** | 1.72 (1.16, 2.55) | 17.91** | 2.29 (1.56, 3.36) | 0.13 | −0.28 (−1.85, 1.29) | 8.39 ** | 5.67 (1.83, 9.51) |

| Non-binary | 4.00 * | 1.42 (1.01, 2.01) | 15.03** | 1.97 (1.40, 2.77) | 0.24 | 0.36 (−1.06, 1.77) | 5.80 * | 4.27 (0.79, 7.74) |

| Gender x Age | - | - | - | - | - | - | 11.90 ** | |

| Trans women | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Trans men | - | - | - | - | - | - | 10.27 ** | −0.20 (−0.32, −0.08) |

| Non-binary | - | - | - | - | - | - | 5.06 * | −0.11 (−0.21, −0.02) |

| n | 870 | 871 | 904 | |||||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tan, K.K.H.; Ellis, S.J.; Schmidt, J.M.; Byrne, J.L.; Veale, J.F. Mental Health Inequities among Transgender People in Aotearoa New Zealand: Findings from the Counting Ourselves Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2862. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17082862

Tan KKH, Ellis SJ, Schmidt JM, Byrne JL, Veale JF. Mental Health Inequities among Transgender People in Aotearoa New Zealand: Findings from the Counting Ourselves Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(8):2862. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17082862

Chicago/Turabian StyleTan, Kyle K.H., Sonja J. Ellis, Johanna M. Schmidt, Jack L. Byrne, and Jaimie F. Veale. 2020. "Mental Health Inequities among Transgender People in Aotearoa New Zealand: Findings from the Counting Ourselves Survey" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 8: 2862. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17082862

APA StyleTan, K. K. H., Ellis, S. J., Schmidt, J. M., Byrne, J. L., & Veale, J. F. (2020). Mental Health Inequities among Transgender People in Aotearoa New Zealand: Findings from the Counting Ourselves Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(8), 2862. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17082862