School-based Physical Activity Interventions in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

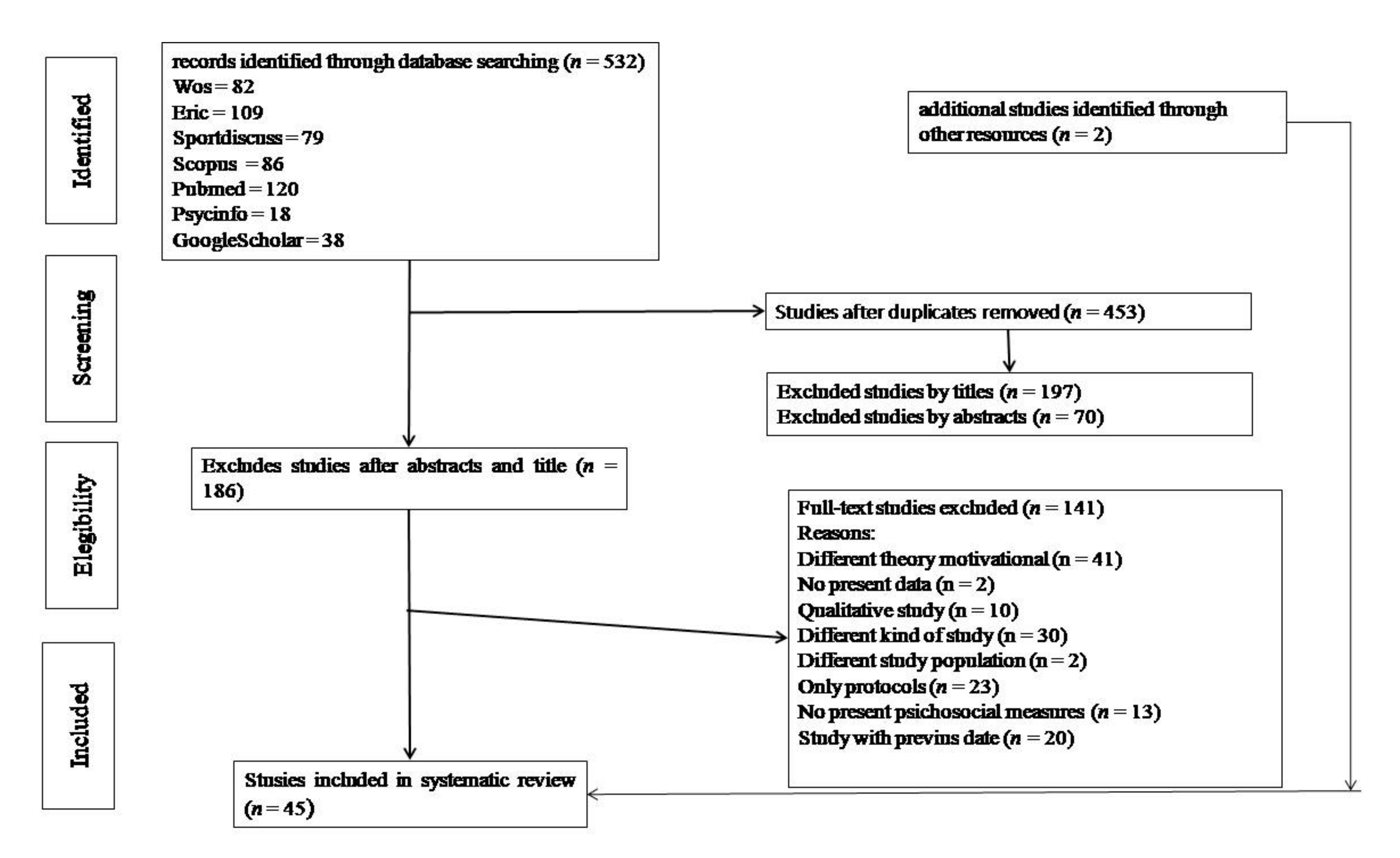

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Limits

2.2. Selection Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction and Reliability

2.4. Evaluation of the Quality and Level of Evidence

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Studies

3.2. Educational Level Uses

3.3. Design of the Programs

3.4. Nature of the Variables

3.5. Outcomes

- What incidence do interventions based on Self-Determination Theory or Achievement Goal Theory have in the curricular or extracurricular school context?

- Do PA levels increase? Do the participants’ psychosocial behaviors modify their self-perception, body image, levels of motivation, quality of life, fun, boredom, and the psychosocial climate?

- What is the recommended duration for the development of an intervention program?

3.6. Focus of Studies and Context

3.7. Outcome on Motivation

3.8. Outcome on Physical and Physiological Behaviors

3.9. Outcome on Psychosocial Effect

3.10. Outcome on Duration of the Program

3.11. Main Effect on the Intervention

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hills, A.P.; King, N.A.; Armstrong, T.P. The contribution of physical activity and sedentary behaviours to the growth and development of children and adolescents: Implications for overweight and obesity. Sports Med. 2007, 37, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspersen, C.J.; Powell, K.E.; Christenson, G.M. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: Definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 1985, 100, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Donnelly, J.E.; Hillman, C.H.; Castelli, D.; Etnier, J.L.; Lee, S.; Tomporowski, P.; Lambourne, K.; Szabo-Reed, A.N. Physical activity, fitness, cognitive function, and academic achievement in children: A systematic review. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2016, 48, 1197–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sevil Serrano, J.; Abós Catalán, Á.; Generelo Lanaspa, E.; Aibar Solana, A.; García-González, L. Importancia del apoyo a las necesidades psicológicas básicas en la predisposición hacia diferentes contenidos en Educación Física. / Importance of support of the basic psychological needs in predisposition to different contents in Physical Education. RETOS Neuvas Tend. Educ. Fis. Deporte Recreacion 2016, 29, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Strong, A.L.; Cederna, P.S.; Rubin, J.P.; Coleman, S.R.; Levi, B. The Current state of fat grafting: A review of harvesting, processing, and injection techniques. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2015, 136, 897–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raboteg-Saric, Z.; Sakic, M. Relations of parenting styles and friendship quality to self-esteem, life satisfaction and happiness in adolescents. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2014, 9, 749–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaha, M.; Hawi, N.S. Relationships among smartphone addiction, stress, academic performance, and satisfaction with life. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 57, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagenauer, G.; Gläser-Zikuda, M.; Moschner, B. University students’ emotions, life-satisfaction and study commitment: A self-determination theoretical perspective. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2018, 42, 808–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diseth, Å.; Samdal, O. Autonomy support and achievement goals as predictors of perceived school performance and life satisfaction in the transition between lower and upper secondary school. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2014, 17, 269–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grao-Cruces, A.; Nuviala, A.; Fernandez-Martinez, A.; Perez-Turpin, J.A. Association of physical self-concept with physical activity, life satisfaction and Mediterranean diet in adolescents. Kinesiology 2014, 46, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Cervelló, E.; Peruyero, F.; Montero, C.; González-Cutre, D.; Beltrán-Carrillo, V.J.; Moreno-Murcia, J.A. Ejercicio, bienestar psicológico, calidad de sueño y motivación situacional en estudiantes de educación física. Cuadernos de Psicología del Deporte 2014, 14, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aelterman, N.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Van den Berghe, L.; De Meyer, J.; Haerens, L. Fostering a need-supportive teaching style: Intervention effects on physical education teachers’ beliefs and teaching behaviors. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2015, 36, 595–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, J.G.; Portolés, A. Recomendaciones de actividad física y su relación con el rendimiento académico en adolescentes de la Región de Murcia. RETOS Neuvas Tend. Educ. Fis. Deporte Recreacion 2016, 29, 100–104. [Google Scholar]

- Shadish, W.R.; Cook, T.D.; Campbell, D.T. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental for Generalized Designs Causal Inference. In Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Consulting Psychologists Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sallis, J.F.; Owen, N.; Fisher, E. Ecological models of health behavior. In Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lazowski, R.A.; Hulleman, C.S. Motivation interventions in education. Rev. Educ. Res. 2016, 86, 602–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järvenoja, H. Socially Shared Regulation of Motivation and Emotions in Collaborative Learning; University of Oulu: Oulu, Finland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, C. Achievement goals and the classroom motivational climate. In Student Perceptions in the Classroom; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 1992; pp. 327–348. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, J.G. The competitive ethos and democratic education. Choice Rev. Online 1989, 27, 1049. [Google Scholar]

- Amado, D.; Del Villar, F.; Leo, F.M.; Sánchez-Oliva, D.; Sánchez-Miguel, P.A.; García-Calvo, T. Effect of a multi-dimensional intervention programme on the motivation of physical education students. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e85275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, S.H.; Reeve, J.; Song, Y.-G. A teacher-focused intervention to decrease pe students’ amotivation by increasing need satisfaction and decreasing need frustration. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2016, 38, 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Calvo, T.; Sánchez-Oliva, D.; Leo, F.M.; Amado, D.; Pulido, J.J. Effects of an intervention programme with teachers on the development of positive behaviours in Spanish physical education classes. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2015, 21, 572–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Overview of self-determination theory: An organismic dialectical perspective. In Handbook on Self-Determination Research; University Rochester Press: Rochester, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.; Deci, E. Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development and Wellness; Sevent Avenue: Suite, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Prentice, M.; Halusic, M.; Sheldon, K.M. Integrating theories of psychological needs-as-requirements and psychological needs-as-motives: A two process model. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass. 2014, 8, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, J.G. Achievement motivation: Conceptions of ability, subjective experience, task choice, and performance. Psychol. Rev. 1984, 91, 328–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treasure, D.C.; Roberts, G.C. Applications of achievement goal theory to physical education: Implications for enhancing motivation. Quest 1995, 47, 475–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolters, C.A. Advancing Achievement Goal Theory. J. Educ. Psychol. 2004, 96, 236–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaakkola, T.; Ntoumanis, N.; Liukkonen, J. Motivational climate, goal orientation, perceived sport ability, and enjoyment within Finnish junior ice hockey players. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2016, 26, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, H.E.; Atkin, A.J.; Panter, J.; Wong, G.; Chinapaw, M.J.M.; van Sluijs, E.M.F. Family-based interventions to increase physical activity in children: A systematic review, meta-analysis and realist synthesis. Obes. Rev. 2016, 17, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, I.; LeBlanc, A.G. Systematic review of the health benefits of physical activity and fitness in school-aged children and youth. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010, 7, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Sluijs, E.M.F.; McMinn, A.M.; Griffin, S.J. Effectiveness of interventions to promote physical activity in children and adolescents: Systematic review of controlled trials. Br. J. Sports Med. 2008, 42, 653–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo, P.; Grao-Cruces, A.; Pérez-Ordás, R. Teaching personal and social responsibility model-based programmes in physical education: A systematic review. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ariza, A.; Grao-Cruces, A.; de Loureiro, N.E.M.; Martínez-López, E.J. Influence of physical fitness on cognitive and academic performance in adolescents: A systematic review from 2005–2015. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2017, 10, 108–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, P.J.; Carraça, E.V.; Markland, D.; Silva, M.N.; Ryan, R.M. Exercise, physical activity, and self-determination theory: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Piñero, J.; Artero, E.G.; España-Romero, V.; Ortega, F.B.; Sjöström, M.; Suni, J.; Ruiz, J.R. Criterion-related validity of field-based fitness tests in youth: A systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2010, 44, 934–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebire, S.J.; Edwards, M.J.; Fox, K.R.; Davies, B.; Banfield, K.; Wood, L.; Jago, R. Delivery and receipt of a self-determination-theory-based extracurricular physical activity intervention: Exploring theoretical fidelity in action 3:30. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2016, 38, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riiser, K.; Løndal, K.; Ommundsen, Y.; Småstuen, M.C.; Misvær, N.; Helseth, S. The outcomes of a 12-week internet intervention aimed at improving fitness and health-related quality of life in overweight adolescents: The young & active controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e114732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abós, Á.; Sevil, J.; Julián, J.A.; Abarca-Sos, A.; García-González, L. Improving students’ predisposition towards physical education by optimizing their motivational processes in an acrosport unit. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2016, 23, 444–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amado, D.; Sánchez-Miguel, P.A.; Molero, P. Creativity associated with the application of a motivational intervention programme for the teaching of dance at school and its effect on the both genders. PLoS ONE 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babic, M.J.; Smith, J.J.; Morgan, P.J.; Lonsdale, C.; Plotnikoff, R.C.; Eather, N.; Skinner, G.; Baker, A.L.; Pollock, E.; Lubans, D.R. Intervention to reduce recreational screen-time in adolescents: Outcomes and mediators from the ‘Switch-Off 4 Healthy Minds’ (S4HM) cluster randomized controlled trial. Prev. Med. 2016, 91, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechter, B.E.; Dimmock, J.A.; Jackson, B. A cluster-randomized controlled trial to improve student experiences in physical education: Results of a student-centered learning intervention with high school teachers. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2019, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortoli, L.; Bertollo, M.; Vitali, F.; Filho, E.; Robazza, C. The effects of motivational climate interventions on psychobiosocial states in high school physical education. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport. 2015, 86, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronikowski, M.; Bronikowska, M.; Maciaszek, J.; Glapa, A. Maybe it is not a goal that matters: A report from a physical activity intervention in youth. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 2016, 58, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, S.H.; Reeve, J.; Ntoumanis, N. A needs-supportive intervention to help PE teachers enhance students’ prosocial behavior and diminish antisocial behavior. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2018, 35, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, R.; García-López, L.M.; Serra-Olivares, J. Sport education model and self-determination theory. Kinesiology 2016, 48, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Rio, J.; Sanz, N.; Fernandez-Cando, J.; Santos, L. Impact of a sustained Cooperative Learning intervention on student motivation. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2016, 22, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, E.; Coterón López, J. The effects of a physical education intervention to support the satisfaction of basic psychological needs on the motivation and intentions to be physically active. J. Hum. Kinet. 2017, 59, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Gao, Z.; Hannon, J.C.; Allen, B.; Burns, R.D. Effect of spark on physical activity, cardiorespiratory endurance, and motivation in middle-school students. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2016, 47, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girelli, L.; Manganelli, S.; Alivernini, F.; Lucidi, F. Una intervención basada en la teoría de la autodeterminación para promover la alimentación saludable y la actividad física en los niños en edad escolar. Cuad. Psicol. Deporte 2016, 16, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- González-Cutre, D.; Ferriz, R.; Beltrán-Carrillo, V.J.; Andrés-Fabra, J.A.; Montero-Carretero, C.; Cervelló, E.; Moreno-Murcia, J.A. Promotion of autonomy for participation in physical activity: A study based on the trans-contextual model of motivation. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 34, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Cutre, D.; Sierra, A.C.; Beltrán-Carrillo, V.J.; Peláez-Pérez, M.; Cervelló, E. A school-based motivational intervention to promote physical activity from a self-determination theory perspective. J. Educ. Res. 2016, 111, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gråstén, A.; Yli-Piipari, S.; Watt, A.; Jaakkola, T.; Liukkonen, J. Effectiveness of school-initiated physical activity program on secondary school students’ physical activity participation. J. Sch. Health 2015, 85, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gråstén, A.; Yli-Piipari, S. The patterns of moderate to vigorous physical activity and physical education enjoyment through a 2-year school-based program. J. Sch. Health 2019, 89, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajar, M.S.; Rizal, H.; Kueh, Y.C.; Muhamad, A.S.; Kuan, G. The effects of brain breaks on motives of participation in physical activity among primary school children in Malaysia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- How, Y.M.; Whipp, P.; Dimmock, J.; Jackson, B. The effects of choice on autonomous motivation, perceived autonomy support, and physical activity levels in high school physical education. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2013, 32, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanlayanee, N.; Tuicomepee, A.; Kiamjarasrangsi, W.; Sithisarankul, P. Can the weight reduction program improve obese thai adolescents’ body mass index and autonomous motivation? J. Nepal Paediatr. Soc. 2017, 37, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkonen, J.; Yli-Piipari, S.; Kokkonen, M.; Quay, J. Effectiveness of a creative physical education intervention on elementary school students’ leisure-time physical activity motivation and overall physical activity in Finland. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, J.A.; Girard, S.; Lemoyne, J. Tracing adolescent girls’ motivation longitudinally: From fit club participation to leisure-time physical activity. Percept. Mot. Skills 2019, 126, 986–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonsdale, C.; Rosenkranz, R.R.; Sanders, T.; Peralta, L.R.; Bennie, A.; Jackson, B.; Taylor, I.M.; Lubans, D.R. A cluster randomized controlled trial of strategies to increase adolescents’ physical activity and motivation in physical education: Results of the Motivating Active Learning in Physical Education (MALP) trial. Prev. Med. 2013, 57, 696–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lonsdale, C.; Lester, A.; Owen, K.B.; White, R.L.; Peralta, L.; Kirwan, M.; Diallo, T.M.; Maeder, A.J.; Bennie, A.; MacMillan, F.; et al. An internet-supported school physical activity intervention in low socioeconomic status communities: Results from the Activity and Motivation in Physical Education (AMPED) cluster randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Sports Med. 2017, 53, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubans, D.R.; Smith, J.J.; Plotnikoff, R.C.; Dally, K.A.; Okely, A.D.; Salmon, J.; Morgan, P.J. Assessing the sustained impact of a school-based obesity prevention program for adolescent boys: The ATLAS cluster randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016, 13, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicaise, V.; Kahan, D. Psychological changes among muslim students participating in a faith-based school physical activity program. Res. Q. Exerc. Sports 2013, 84, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, S.E.; Bycura, D.K.; Warren, M. A Physical education intervention effects on correlates of physical activity and motivation. Health Promot. Pract. 2017, 19, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlman, D. Manipulation of the self-determined learning environment on student motivation and affect within secondary physical education. Phys. Educ. 2013, 70, 413–428. [Google Scholar]

- Yli-Piipari, S.; Layne, T.; Hinson, J.; Irwin, C. Motivational pathways to leisure-time physical activity in urban physical education: A cluster-randomized trial. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2018, 37, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaresma, A.M.; Palmeira, A.L.; Martins, S.S.; Minderico, C.S.; Sardinha, L.B. Effect of a school-based intervention on physical activity and quality of life through serial mediation of social support and exercise motivation: The PESSOA program. Health Educ. Res. 2014, 29, 906–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R.E.; Beauchamp, M.R.; Blanchard, C.M.; Bredin, S.S.D.; Warburton, D.E.R.; Maddison, R. Use of in-home stationary cycling equipment among parents in a family-based randomized trial intervention. J. Sci. Med. Sports 2018, 21, 1050–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, L.B.; Wen, F.; Ling, J. Mediators of physical activity behavior change in the «girls on the move» intervention. Nurs. Res. 2019, 68, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rokka, S.; Kouli, O.; Bebetsos, E.; Goulimaris, D.; Mavridis, G. Effect of dance aerobic programs on intrinsic motivation and perceived task climate in secondary school students. Int. J. Instr. 2019, 12, 641–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Oliva, D.; Pulido-González, J.J.; Leo, F.M.; González-Ponce, I.; García-Calvo, T. Effects of an intervention with teachers in the physical education context: A Self-Determination Theory approach. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevil, J.; Abós, Á.; Julián, J.A.; Murillo, B.; García-González, L. Gender and situational motivation in physical education: The key to the development of intervention strategies. RICYDE Rev. Int. Cienc. Deporte 2015, 11, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevil, J.; Abós, Á.; Aibar, A.; Julián, J.A.; García-González, L. Gender and corporal expression activity in physical education: Effect of an intervention on students’ motivational processes. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2016, 22, 372–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevil Serrano, J.; Abós Catalán, Á.; Sanz Remacha, M.; García-González, L. El “lado claro” y el “lado oscuro” de la motivación en educación física: Efectos de una intervención en una unidad didáctica de atletismo. Rev. Iberoam. Diagn. Eval. Aval. Psicol. 2018, 46, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, S.; Brennan, D.; Hanna, D.; Younger, Z.; Hassan, J.; Breslin, G. The effect of a school-based intervention on physical activity and well-being: A non-randomised controlled trial with children of low socio-economic status. Sports Med. Open 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.J.; Morgan, P.J.; Lonsdale, C.; Dally, K.; Plotnikoff, R.C.; Lubans, D.R. Mediators of change in screen-time in a school-based intervention for adolescent boys: Findings from the ATLAS cluster randomized controlled trial. J. Behav. Med. 2016, 40, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nation-Grainger, S. ‘It’s just PE’ till ‘It felt like a computer game’: Using technology to improve motivation in physical education. Res. Pap. Educ. 2017, 32, 463–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilga, H.; Hein, V.; Koka, A. Effects of a web-based intervention for PE teachers on students’ perceptions of teacher behaviors, psychological needs, and intrinsic motivation. Percept. Mot. Skills 2019, 126, 559–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Human Agency in Social Cognitive Theory. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 1175–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kriemler, S.; Meyer, U.; Martin, E.; Van Sluijs, E.M.F.; Andersen, L.B.; Martin, B.W. Effect of school-based interventions on physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents: A review of reviews and systematic update. Br. J. Sports Med. 2011, 45, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, G.M. The New Science of Wise Psychological Interventions. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 23, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PICOS | Eligibility Criteria |

|---|---|

| Population | Children and adolescents between six and eighteen years old |

| Intervention | Intervention studies based on motivation for the promotion of physical activity and psychosocial benefits |

| Comparison | Compare an intervention group based on motivational principles that promotes physical activity through different strategies with a control group |

| Outcome | Any physical or psychosocial outcome is measured or reported.Psychosocial outcomes: individual’s social and psychological aspects including, but not limited to cognitions, emotions, and mental health |

| Authors (Year) [Reference] | a | b | c | d | e | Total Score | Quality Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abós et al. (2016) [41] | 1 | 2 | 2 | No | Yes | 5 | HQ |

| Amado et al. (2014) [21] | 1 | 1 | 2 | No | Yes | 4 | MQ |

| Amado et al. (2017) [42] | 2 | 2 | 2 | No | Yes | 6 | HQ |

| Babic et al. (2016) [43] | 2 | 2 | 2 | Yes | Yes | 6 | HQ |

| Bechter et al. (2019) [44] | 2 | 2 | 2 | Yes | Yes | 6 | HQ |

| Bortolí et al. (2015) [45] | 2 | 2 | 2 | No | Yes | 6 | HQ |

| Bronikowskiet al. (2016) [46] | 2 | 2 | 2 | Yes | No | 6 | HQ |

| Cheon et al. (2016) [22] | 2 | 2 | 2 | Yes | Yes | 6 | HQ |

| Cheon et al. (2018) [47] | 2 | 2 | 2 | Yes | Yes | 6 | HQ |

| Cuevas et al. (2016) [48] | 2 | 2 | 1 | Yes | Yes | 5 | HQ |

| Fernández-Rio et al. (2016) [49] | 2 | 2 | 1 | Yes | Yes | 5 | HQ |

| Franco et al. (2017) [50] | 1 | 2 | 1 | No | Yes | 4 | MQ |

| Fu et al. (2016) [51] | 2 | 2 | 2 | No | N/a | 6 | HQ |

| García-Calvo et al. (2015) [23] | 2 | 2 | 2 | No | No | 6 | HQ |

| Girelli et al. (2016) [52] | 2 | 2 | 2 | Yes | No | 6 | HQ |

| González-Cutre et al. (2014) [53] | 1 | 2 | 1 | No | N/a | 4 | MQ |

| González-Cutre et al. (2016) [54] | 2 | 2 | 2 | No | Yes | 6 | HQ |

| Grasten et al. (2015) [55] | 2 | 2 | 1 | No | No | 5 | HQ |

| Grasten et al. (2019) [56] | 2 | 2 | 2 | No | No | 6 | HQ |

| Hajar et al. (2019) [57] | 2 | 1 | 1 | Yes | N/a | 4 | MQ |

| How et al. (2013) [58] | 2 | 2 | 2 | Yes | No | 6 | HQ |

| Kanlayane et al. (2017) [59] | 2 | 2 | 1 | Yes | Yes | 5 | HQ |

| Kokkonen et al. (2018) [60] | 2 | 1 | 2 | No | Yes | 5 | HQ |

| Laroche et al. (2019) [61] | 2 | 2 | 2 | No | No | 6 | HQ |

| Lonsdale et al. (2013) [62] | 2 | 2 | 2 | Yes | Yes | 6 | HQ |

| Lonsdale et al. (2017) [63] | 2 | 2 | 2 | Yes | Yes | 6 | HQ |

| Lubans et al. (2016) [64] | 2 | 2 | 2 | Yes | Yes | 6 | HQ |

| Nicaise et al. (2014) [65] | 1 | 2 | 2 | N/a | N/a | 5 | HQ |

| Palmer et al. (2018) [66] | 2 | 2 | 1 | No | No | 5 | HQ |

| Perlman et al. (2013) [67] | 2 | 2 | 2 | Yes | Yes | 6 | HQ |

| Piipari et al. (2018) [68] | 2 | 2 | 2 | Yes | Yes | 6 | HQ |

| Quaresma et al. (2014) [69] | 2 | 2 | 2 | Yes | N/a | 6 | HQ |

| Riiser et al. (2014) [40] | 2 | 2 | 1 | No | N/a | 5 | HQ |

| Rhodes et al. (2018) [70] | 2 | 2 | 2 | Yes | Yes | 6 | HQ |

| Robbins et al. (2019) [71] | 2 | 2 | 2 | Yes | N/a | 6 | HQ |

| Rokka et al. (2019) [72] | 2 | 1 | 1 | No | No | 4 | MQ |

| Sánchez-Oliva et al. (2017) [73] | 2 | 2 | 2 | Yes | No | 6 | HQ |

| Sebire et al. (2016) [39] | 2 | 2 | 2 | Yes | Yes | 6 | HQ |

| Sevilet al. (2015) [74] | 2 | 2 | 1 | No | No | 5 | HQ |

| Sevil et al. (2016) [75] | 2 | 2 | 2 | Yes | No | 6 | HQ |

| Sevil et al. (2018) [76] | 2 | 2 | 2 | Yes | No | 6 | HQ |

| Shannon et al. (2018) [77] | 2 | 2 | 2 | No | No | 6 | HQ |

| Smith et al. (2017) [78] | 2 | 2 | 2 | Yes | N/a | 6 | HQ |

| Stephen Nation Grainger (2017) [79] | 1 | 2 | 1 | Yes | N/a | 4 | MQ |

| Tilga et al. (2019) [80] | 2 | 2 | 2 | Yes | Yes | 6 | HQ |

| Author (Year) [Reference] | Objective | Participants | Variables | Intervention Time | Data Sources | Results | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abós et al. (2016) [41] | To evaluate the effectiveness of applications of strategies based on TARGET, and the predisposition towards PA | 35 students 15–17 yearsold | Climate scale of perceived motivation. Questionnaire to assess the BPN support Predisposition towards PA | The intervention was based on 12 acrosport lessons through the support of BPN. A first measure was taken at the beginning of the unit and two weeks after the end of the lessons. 2 teachers were instructed throughout 60h so that the intervention program was correctly fulfilled | Quasi-experimental design with non-equivalent groups. | Tests of normality, descriptive analysis and MANOVA were carried out | The importance in the learning of the task orientation in the motivation The importance of support for BPN can increase the predisposition towards PA |

| Amado et al. (2014) [21] | Verify the effect produced on the motivation of PE students of a multi-dimensional programme in dance teaching sessions | 47 students from 14 to 16 years old | Self determination level BPN | 12 teachin session, with two weekly of 50 min session throught week | Quasi-experimental design with non-equivalent groups | Descriptive analysis ANOVA and MANOVA were carried out | The programme’s usefulness in increasing the students’ motivation towards this content, which is so complicated for teachers of this area to develop |

| Amado et al. (2017) [42] | Find out gender differences in motivational processes, affective consequences, and behavior after a dance education program | 12 teachers 921 students from 11 to 17 years old | Perception of support from the BPN. Perception of satisfaction of the BPN. Levels of motivation Utility. Enjoyment and effort Positive behavior | Intervention program covered a total of 35H, 12 sessions of a didactic unit | Experimental design CG and EG, in moments of pretest, posttest, | Descriptive, MANOVA, and Analysis of the variance of three factors, with two intersubject factors (sig differences in gender) | A creative methodology in the development of content increases motivation |

| Babic et al. (2016) [43] | Evaluate the impact of the “Switch-off 4 Healthy Minds” (S4HM) intervention onrecreational screen-time in adolescents. | 322 adolescents from 12 to 14 years old | Sedentary activity PA Motivation to limit screen time BMI Psichological well-being Distress Physical self-concept | Interventionprogramover 6 month | Cluster randomized control trial with CG and EG | Descriptivesanálisis Mediationanalysis | The present trial was ineffective in its primary aim of reducing recreational screen-time. Significant intervention effects were observed for participants” autonomous motivation to limit screen-time, which mediated changes in screen-time |

| Bechter et al. (2019) [44] | Implement a teacher training program—based on well-established pedagogical strategies to improve key student outcomes (e.g., PE motivation, self-efficacy) | 554 hightschools students from 12 to 16 years old, and 19 PE teachers | Teachers learning strategies Motivation BPN satisfaction Effort PE learning efficacy | Intervention program was based on two time of measures (i.e., initial measure and follow up) and the intervention was developed in five week with teacher learning strategies | Experimental design CG and EG, in moments of base line and follow up | Descriptive statistics MANOVA, Linear mixed models | Findings demonstrate that teacher training programs targeting the use of student-centered teaching strategies may be beneficial for promoting desirable motivational outcomes, and provide insight into the mechanisms responsible for these positive in-class effects |

| Bortolí et al. (2015) [45] | Examine the effect of motivational climate manipulation on students’ perception of climate, taking into account the effect of individual goal orientation. | 108 female students from 14 to 15 years old | Perceived motivational climate Goal orientations Psychobiosocial state | We conducted three 2-h seminars with teachers before the data collection and intervention, as well as three meetings during the treatment that lasted approximately 40 min each. Each teacher was responsible for a “group involved in the task” and a “group committed to the ego” | The design was 2 × 2 2 groups during two times and the intervention was for 6 weeks, twice a week | Analysis of descriptive statistics, and ANCOVA of repeated measures | Findings highlight the link between several aspects of the multidimensional experience related to emotion in PE, in which the emotional and motivational contents are consistent with the content of performance |

| Bronikowski et al. (2016) [46] | To assess the effectiveness of two different goal orientations for the increase and maintenance of PA in adolescents | 65 adolescentsof 17 yearsold | PA Support for teachers and classmate Self-efficacy | An intervention was developed in 2 different intervention groups, each with different strategies. 8 weeksduration | An experimental design was used, Pre-test start and posttest at the end | Descriptive statistics and wilcoxon test and Mann Whitney U were used, ANOVA and Post hoc test were used | The teacher’s support is more effective, than the objectives and strategies for the achievement of improving the MVPA |

| Cheon et al. (2016) [22] | Test an intervention by the teacher through a more autonomous teaching style in detraction from a more controlling style that promotes BPN | 1017 students 19 teachers | Support for teacher autonomy Support for the teacher’s style of control BPN satisfaction and frustration Commitment in the class and amotivation | 19 teachers, an instruction of 2 h and 30 to introduce the teaching of autonomy support. After 2 h focused on the development of specific skills in autonomous learning, part 3 of the instruction was through 2 h of discussion, they shared their experiences in the development of autonomy, the intervention was 8 months | CG (10) and EG (9) in 4 different times | Normality tests, descriptive statistics, correlations, T test, analysis of repeated measures | The satisfaction of BPN was increased through a teacher-centered intervention |

| Cheon et al. (2018) [47] | Implement an intervention program based on support for the autonomy of PE teachers to promote prosocial behaviors in students | 33 teachers y 1824 students | Scoring ratios of teacher motivation styles Perception of prosocial and antisocial behavior according to the teacher Students’ perception of the teacher’s support for autonomy and style BPN satisfaction of students Prosocial and antisocial behavior of students Perception of deception | 3 measures collected in the participating teachers: the first and second 2 weeks before starting the course, and the third during week 6 of the intervention. The intervention of the students took 19 weeks | 15 teachers and their students’EG, and 18 teachers and their students CG | Descriptive; T Test; Multilevel analysis of repeated measures and finally calculation of the effect size; Structural equation model | This intervention has benefits for students with commitment, learning, motivation and psychosocial behaviors |

| Cuevas et al. (2016) [48] | Find out the impact of a sports education program on PE students regarding the levels of motivation | 86 participants from 15 to 17 yearsold | Regulation of motivation. BPN thwarting Enjoy and boredom Intention to be physically active | 19 lessons of a volleyball didactic unit (2× week) | Experimental Design CG and EG. CG traditional class and EG sports education program | Descriptive and ANOVA | No significant changes were found, although the changes in intrinsic motivation based on sports motivation should be highlighted |

| Fernández-Rio et al. (2016) [49] | Assess the impact of a cooperative learning program on student motivation | 249 students, and 4 teachers in 4 different schools from 12 to 16 years old | Motivation Cooperation Perception of the students (open-ended question) | 16-week intervention program (2 h per week) based on instruction to teachers through seminars | A design based on pretest-posttest, quasi-experimental, based on comparisons | Descriptive analyzes, Wilcoxon test, and T tests | The study showed that an intervention based on cooperative learning can increase the most self-determined types of motivation |

| Franco et al. (2017) [50] | Evaluate the effects of an intervention based on the support of BPN and the satisfaction of these needs | 53 stundets from 12 to 15 yearsold | BPN Intrinsic motivation Intention to be physically active Enjoyment | A pre-post quasi-experimental design with two groups through 24 sessions (3 months), 10 h in strategies (experimental teacher training) was used | Intervention of 3 months, 2 measures (pre-post) 2 groups (CG and EG) | Kolmogorov test to assess the normality of the data. And the Mann Whitney U to evaluate differences | The usefulness of an intervention that incorporates strategies aimed at supporting BPN in satisfaction with autonomy and competence, and intrinsic motivation |

| Fu et al. (2016) [51] | To assess the effect of the SPARK program on levels of PA, cardiorespiratory endurance and motivation. In addition, evaluate the differences with respect to gender | 175 students from 6th and 7th grade (82 boys, 92 girls) | PA in the classes Cardiorespiratory resistance Perceived competence Enjoyment | 9-week program; 2 measurements 1 pretest and one posttest. The pedometers were used at the beginning (1st week) and also during the last week | CG and EG experimental design, in pretest and posttest moments | Descriptive statistics. T Tests and Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) | The program demonstrated the effects on PA and motivation |

| García-Calvo et al. (2015) [23] | Measure the effects of a multidisciplinary intervention with teachers in the development of positive behaviors in PE classes | 20 teachers and 777 students between 12 and 16 years | Positive behavior Positive behavior support | The entire study was developed from September 2011 to April 2012, but the intervention period was carried out from January to March | A quasi-experimental design with a CG and three groups (training program group, didactic unit group integral training group) | Descriptive statistics of each variable, pretest-poles, and the performance of a MANOVA and ANCOVA | The effectiveness of the intervention was demonstrated through the promotion of positive behaviors during PE classes |

| Girelli et al. (2016) [52] | Test the effectiveness of an intervention based on the Self-Determination Theory developed in Italy to promote healthy lifestyles in terms of PA and eating habits | 866 participants, from 6 to 11 years old, 23 classes and 10 schools | Attitude toward PA Motivation towards PA Moderate daily exercise Daily sedentary activities Attitude towards the intake of healthy food. Motivation towards PA, daily consumption of healthy food. Daily snack consumption with high calories | 9-month intervention with a minimum of 2 h per week, the CG only received one food seminar. Teachers and instructors were previously trained | Quasi-experimental design, with 2 Pre and Post measurements in a CG and a EG | Descriptive and exploratory statistics, ANOVA, correlation and intervention analysis were performed | The effects of the intervention program were demonstrated on a temporary basis, improving lifestyle and PA through healthy eating |

| González-Cutre et al. (2014) [53] | Analyse the effects of a school-based intervention to promote PA, utilising the postulates of the trans-contextual model of motivation | 47 elementary schools students from 11 to 12 years old | Autonomy support Motivation in PE Motivation to leasure time Theory of planned behavior PA | Five week intervention. The intervention programme was conducted through videos with two session of 50 min per week | Quasi-experimental design, with 2 Pre and Post measurements in a CG and a EG | Non-parametric test for independent samples (Mann–WhitneyU) Differences with non-parametric test for related samples (Wilcoxon) | The study shows that this type of intervention couldallow the students to identify the benefits of PA and to integrate it intotheirlifestyle, thus increasing PA during their leisure time |

| González-Cutre et al. (2016) [54] | Assess the effect of a multidimensional intervention program to promote PA based on the Self-Determination Theory | 88 students between 14 and 17 years old | Autonomy support BPN Types of motivation Physical self-concept Levels of PA | 6-month intervention, data collection in 4 moments, before, after the first didactic unit, end of program (6 months) and follow-up (12), the questionnaires were filled in two different sessions | CG and EG × 4 different times | Normality tests, descriptive statistics, Man Withney U Multiple comparisons with the Wilcoxon test Size effect with Cliff delta | The effectiveness of a multidimensional intervention for the promotion of PA at school was demonstrated, however 6 months after the intervention the effects were lost |

| Grasten et al. (2015) [55] | To evaluate the effectiveness of an initiation program in the school of PA during a year | 847 students from 12 to 14 years old | Motivational climate Goal orientations Auto report of moderate vigorous PA | Teachers were prepared through 4 workshops. To then intervene on the students. Theinterventionprocesswasduringoneyear in total. | Experimental design CG and EG, in pretest and posttest moments | Descriptive statistics. T-Tests and Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), structural equation modeling | The findings of this study suggest that exposing students to additional PA throughout the school days and providing access to equipment and facilities during recess and breaks may be the most tangible way to increase their PA |

| Grasten et al. (2019) [56] | To examine the effectiveness of a programm focused on increasing mvpa and PE enjoyment | 661 students from 11 to 13 years old and 46 teachers | Motivational climate MVPA (Prochaska) PE enjoyment | Teachers were prepared through 4 workshops. Interventions were made academic breaks giving greater autonomy with respect to facilities and materials | Longitudinal study (two years) with CG and EG in three measures | Descrptive statistics. Correlations, T-Test and path model | the MVPA did not increase and the enjoyment remained over time |

| Hajar et al. (2019) [57] | measure the efects of brain breaks on motives of participation in PA among primary school children | 335 students from 10 to 11 years old | Demographic information enjoyment, mastery, competition ego, appearance, afiliation, physical condition, and psychological condition (PALMS-Y) | brain breaks activities, five minutes, five times per week, spread out for a period offourmonths | Cuasi-Experimental disign CG and EG, in pretest and posttest moments | Descrptivestatistics.Mixed factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA) | Brain breaks is successful in maintaining students’ motives for PA in four of the seven factors (enjoyment, competition, appearance, and psychological condition) |

| How et al. (2013) [58] | Assess an intervention in Pe through the election and see the effect of this on motivation and PA | 257 students (137 intervention and 120 CG) | Motivation towards PE Levels of PA (accelerometers) Learning climate questionnaire | The intervention lasted 15 weeks. One week before the beginning of the study the teachers (4) received 40 min of explanation, all the students were assigned an intervention number. And 2 optionsofchoiceforthestudentswerepresented. | The data presented the following design: CG and EG and two data collection points | Descriptive analyzes, correlations, repeated measures anova, T tests | A system of options in PE classes can encourage support for autonomy and levels of PA in class |

| Kanlayanee et al. (2017) [59] | Assess the effectiveness of a weight reduction program through an improvement in BMI and autonomous motivation | 304 participants | BMI Anthropometric measures Autonomous motivation for the exercise Dietetic self-regulation Autonomous Motivation of PA Autonomous motivation of dietary intakes | 24-week intervention program, measures taken at the beginning, week 12 and week 24 | Experimental Design: CG and EG | Descriptive, T tests, simple and multiple linear regression | The intervention program did not have a sufficient effect on BMI and autonomous motivation |

| Kokkonen et al. (2018) [60] | Assess the effect of an intervention based on creative PE | 382 students from 9 to 11 years old | Motivational climate in PE Motivation towards PA in leisure time PA in general | It was based on two methods of data collection (web, and questionnaire), the methodology was presented in 2 seminars, later some teachers volunteered, CG teachers only focused on the motor goals | A quasi-experimental design with two groups and two data collection points | Normality tests, descriptive statistics, correlations, analysis of covariance, and a structural equation modeling | The intervention had a positive effect on PA in general and suggests that this intervention can increase the motivation of PA in leisure time |

| Laroche et al. (2019) [61] | Evaluate the direct relations between NPB, Autonomous motivation in a context of fitclub in female population | 259 participantsfrom 14–15 yearsold | BPN Autonomous motivation Perceived behavioral control. Subjetive norms Intention PA leisure-time attitude | Two data measurements were collected, the first on the last day of the 8 weeks and the next three weeks after finishing | Longitudinal and quasi-experimental design, 1 EG in two data collection points | Descriptive, Correlations, Pathmodel | It is suggested that PA programs designed for adolescent girls should focus on improving autonomous motivation through opportunities for the development of BPN |

| Lonsdale et al. (2013) [62] | Promote PA | 4 teachers, 16 PE classes, and 288 students | PA Sedentary Support for autonomy Motivation BPN satisfaction | Teachers from different schools were prepared to choose different types of practice during PE classes in one year | 3 of the schools were experimental and 1 control; Experimental design with different moments of data collection: at the beginning, at the end and over time | Descriptive statistics, MANOVA and ANCOVA were used. In addition, a mixed analysis model was developed | The promotion of choice in the intervention provided short-term benefits in PA and in the reduction of sedentary behavior |

| Lonsdale et al. (2017) [63] | Test the effectiveness of an intervention in internet-based learning | 1421 students from 14 schools | Demographic and anthropometric information MVPA through accelerometers Motivational mediators Sedentary behavior | The intervention was based on the learning of the teachers of strategies that improve students’motivation with the use of Internet and electronic resources | Three measures, baseline, post intervention, maintenance of the intervention. | Mixed linear models were used | Increase the level of moderate vigorous PA for adolescents |

| Lubans et al. (2016) [64] | To assess the impact of the ATLAS program on the prevention of obesity in children and adolescents | 361 adolescents aged 12–14 years | Adiposity, PA, sedentary behavior, consumption of sweets, fitness, motivation and skill-competence in resistance training | 20-week intervention that improved school sports programs, through interactive elements, parents, limiting time on the screen | Experimental design CG and EG, in moments of pretest, posttest, and post intervention measured 18 months later | Descriptive and Mixed Model which evaluated the impact of the group | The intervention was successful in producing positive effects but did not affect its objective of preventing obesity. Similarly, itshowedthegreatpotentialofschoolinterventions |

| Nicaise et al. (2014) [65] | Evaluate the effect of a PA program in relation to the Muslim religion | 46 students aged 11–13 years, 43 of them completed all the measures | PA Enjoyment Motivation | The intervention lasted 8 weeks and one of the measures was at 2 weeks and another at 8 weeks | 1 group with pre and post measures | Descriptiveanalysis and MANOVA | This program improved the enjoyment of PA |

| Palmer et al. (2017) [66] | Examine the effect of a program based on a didactic unit on 5 correlations in PA | 300 students of grade 7 (12–13 years old) | PA, motivation towards PA, perceived sports competition, self-efficacy to eliminate barriers, beliefs of sports ability, perceived physical environment | 4-week intervention based on a modified mountain bike unit | Intervention of 4 weeks with 3 groups and three measures pre, post, and follow-up | Descriptive analyzes, ANOVA, chi square | The results did not show main effects in the intervention, although they suggested that PE can influence certain correlations and an autonomous motivation for PA |

| Perlman et al. (2013) [67] | Assess the psychosocial, motivational and affective responses of students in two different learning contexts | 41 EG students and 38 CG (9–10 years old) | BPN support Self-determined motivation Affected Enjoyment | Each class participated in a basketball unit during 4 weeks (16 lessons) | All the lessons were recorded on video and analyzed by a systematic observation system designed by Sarrazin et al. (2006) The systematic observation tool codifies the specific interactions between teachers and students in 15 categories | Descriptive statistics Repeated measurement anova | In general, current findings reinforce the relevance of self-determination within PE and the applied benefits associated with teaching PE using a highly autonomous learning context |

| Piipari et al. (2018) [68] | Evaluate the impact of an autonomous teaching program on students. | 408 students, 11–13 years old, 19 PE classes, and 8 teachers | Support for perceived autonomy Support for the motivation perceived in the PE Autonomous motivation perceived in the exercise Intention to be physically active PA | CG and EG with two different treatments. Three phases of data collection Base line; week 4; and one week after the intervention. The teachers were trained (3 h) how to support autonomy. 8 week intervention | Quasi-experimental design with non-equivalent groups and three moments of data collection | Descriptive Correlations Analysis of covariance Structural Equation Modeling | The evidence that has the support for autonomy in motivation in PE is shown |

| Quaresma et al. (2014) [69] | Assess the effects of social support and regulation of exercise behavior in PA and quality of life | 1042 students from 10 to 16 yearsold | PA Quality of life Motivation Parental and peers support. | The intervention program was developed during 24 months, an increase of 90 min per week, the health and weight sessions were carried out, emphasizing the knowledge of PA and feeding. Theinterventionwasmadebytheteachers | A study of two measures with CG and EG | Descriptive analyzes General lineal model and model of multiple mediators | An increase in parent and peer support in motivation through exercise represent mechanisms associated with high levels of PA and quality of life |

| Riiser et al. (2014) [40] | Evaluate the effectiveness of an internet-based primary care intervention | 120 participants 84 CG and 36 EG 13–15 years old | Cardiorespiratory fitness. Quality of life. PA Self-determined motivation Body image Body mass index | 12-week intervention with three measures: 1st before the intervention, 2nd immediately after, 3rd measurement 1 year after | Experimental Design: CG and EG | Means, minimums and maximums were used and compared with non-parametric tests, and t test, and the effect was calculated through D Cohen | The effectiveness of an Internet-based intervention for the improvement of respiratory fitness and quality of life is demonstrated |

| Rhodes et al. (2018) [70] | Compare the effect on an exergame intervention (exergame bike, standard bike) among children on motivational variables | 73 insufficiently active children from 10–14 years old | Affective attitude (enjoyment, boredom) Instrumental attitude (utility, beneficial) Motivation towards the exercise Subjective norms, Perceived behavior | 13 weeks intervention with thre measures, 1 basseline, 2 (six week), and 3, 13 weeks | Two arm paralel design with EG and CG | Descriptives analyzes, correlation, and path model | Unique exposure research designs do not They accurately reflect the motivations for the long-term exercise game. Also the role of parents can favor an attitude |

| Robbins et al. (2019) [71] | Assess whether constructs derived from the practice of PA are mediated by SDT and health promotion models for a population of adolescent girls | 1519 girls from 12 yearsold | Demographic data (age, etnicithy, race) Perceived benefits scale of the PA Scale of perceived barriers to PA Social support Self-efficacy Enjoy and motivation | 17-week intervention with two measure 1st immediately after 17 week, 2nd measurement 9 month after inervention | A study of two measures with CG and EG | Using R statistical software, linear mixed-effects models and path analysis | Enjoyment of PA and social support for PA may be important mediators of MVPA in underserved young adolescent girls |

| Rokka et al. (2019) [72] | Investigate the effect of a dance aerobic intervention program on intrinsic motivation and perceived motivation climate in schools students | 160 healthy students from 12 to 13 years old | Intrinsic motivation Enjoyment Perceived motivational climate | 10 week intervention (two sesión per week) with two measuremens (i.e., initial measure and final measure) | A study of two measures with CG and EG | Descriptive analyzes, Correlation, T-Test and ANOVA of repeated measure | The intervention programs involved in dancing are a good way to promote motivation, enjoyment through PE classes |

| Sánchez-Oliva et al. (2017) [73] | Analyze the effect of the intervention process to evaluate changes in motivational processes | 21 teachers and 836 students from 12–16 years old | BPN support Satisfaction of the BPN Motivation Intention to be physically active | Teacher preparation program during 15 h. 3 sessions per week 10 weeks | Experimental design CG and EG, in moments of pretest, posttest, and post-intervention measure | Descriptive, Multilevel model and ANCOVA. Boys reported higher scores. 1st grade students scored significantly higher | Positive effects of an intervention program with teachers on the perceived need for support and autonomous motivation within PE clases |

| Sebire et al. (2016) [39] | Evaluate the intervention process through a mixed methodology | 539 children | Motivation towards PA, BPN satisfaction, perception of support for autonomy, support for self-efficacy based on teaching | Intervention of 20 weeks, during the intervention 4 measures were taken, and another assemement 4 months after the intervention | Experimental Design: CG and EG | Descriptive, evidence Code-based transcription for interviews | The intervention was successful and showed that it can influence the motivation for PA. The study demonstrated the effectiveness of mixed methods to support motivation |

| Sevil et al. (2015) [74] | Test genders‘ influence on motivational variables and cognitive and affective consequences along different PE didactic units. | 66 students from 15 to 17 years old | BPN Self determination motivation. Enjoy and boredom Predisposition toward the content | Intervention of four month, of 60 min with two sesión per week | Quasi-experimental design with non-equivalent groups | Normality analysis Descriptive analysis Manova | It is important that curricular contents are developed taking into account the gender variable. Therefore, it is important to develop the BPNs to generate more fun and willingness to exercise |

| Sevil et al. (2016) [75] | Evaluate the effectiveness of an intervention program in a series of motivational variables in a body language teaching unit | 224 studentsfrom 12–14 yearsold | Motivational climate Satisfaction of the BPN Self-determined motivation Enjoyment/satisfaction and boredom | A program for the 55-h EG teacher was prepared according to the guidelines indicated by Braithwaite et al. 2011. In the second stage, a group of experts prepared the DU February-April, two sessions a week, 50 min per sesión | Quasi-experimental design with non-equivalent groups | Descriptive, Manova, and the effect size with the partial Eta Squared static | The results indicated the importance of creating a task-oriented climate in PE classes that will promote the most positive experiences |

| Sevil et al. (2018) [76] | Assess the effects of an intervention program in the interpersonal teaching style and a series of motivational variables and consequences present in the “bright side” and the “dark side” of the motivation | 103 students | Support for BPN Motivational climate BPN in the field of the PE BPNES satisfaction EFNP thwarting Self-determined motivation Fun/Satisfaction and boredom Predisposition to content Defiantopposition | Intervention of 8 sessions plus 1 additional session of Didactic Unit (athletics). Teacher training of 30 h (2 teachers). 2 pretest and posttestmeasurements | Experimental Design CG and EG. | Descriptive, Manova, and effect size through Partial Eta Squared (η2p) | The intervention program is effective in both genders, promoting even better results in this content in boys |

| Shannon et al. (2018) [77] | Analyze the effect of a choice program on health through a model of autonomy support, BPN satisfaction, intrinsic motivation with PA and well-being | 155 participants | MVPA (accelerometers) Wellness Screen time Support for autonomy NPB satisfaction Motivation (4 scales) | 2 groups × 2 measures. The data was collected in week 0 and week 11 The intervention period was 10 weeks during the school period using 2 h and 15 total minutes per week | Experimental design CG and EG, in pretest and posttest moments. | Descriptive statistics were used and two mediating models (1 with PA and another with welfare) | The study showed that this intervention design improves the MVPA and the welfare through the improvement of support in the autonomy |

| Smith et al. (2016) [78] | Assess the effect of the program on the prevention of obesity | 361 adolescents, 12–14 years old from 14 high schools and 2 teachers | Demographic data Screen time Motivation to limit screen time Screen time rules in the family home | School program of 20 weeks (3 s × 20 min of information from researchers to students, 20 × 90 min sessions of PA, 6 × 20 tutorials on eating habits, and news bulletins screen time to parents | Experimental design with different moments of data collection: at the beginning, at 4 months and at 18 months | Multilevelmediationanalysis | Increasing autonomous motivation to limit screen time can be a useful strategy to address this widespread behavior |

| Stephen Nation Grainger, (2017) [79] | Improve levels of physical exercise, using a PA monitor | 10 studentsfrom 14–15 yearsold | Motivation PA through smart watch Qualitative method (interview) | It was based on a 6-week intervention, where the EG received feed-back after the PE class. | A study of two measures with CG and EG | Normality tests, T tests and correlations were used | A feed-back through technology can increase motivation in PE classes |

| Tilga et al. (2019) [80] | Interventions based on self-determination theory to help teachers support their students’ autonomy | 321 students from 10–15 years old, and 28 PE teachers | Multidimensional autonomy-supportive behavior Multidimensional controlling behavior. Perceived need satisfaction and need frustration. Intrinsicmotivation | 9 weeks intervention, where the EG has three measure (i.e., baseline, 4 weeks, follow up 9 weeks), and CG two measure (i.e., baseline and follow up) | A study experimental with CG and EG | Descriptive statics, Chi square, T tests, and ANCOVAS | This study provides initial evidence that WB-ASIP might increase the likelihood that teachers change their behavior, which, in turn, may facilitate students’ psychological needs satisfaction and motivation toward PE. |

| Studies | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Concepts | Intervention Variables | After Intervention Outcomes | Outcome in Control Group |

| Motivation | Intrinsic regulation | [48,49,50,53] Increasing to PE; [42,54,61,64,65,70,74,76,77,80] | [48,50] decrease to PE |

| Integrated regulation | [54,61] | ||

| Identified regulation | [21,48,49,53] Increasing to PE; [42,44,54,61,64,65] Decreasing; [39,70,76,77,79] | [48,53] | |

| Autonomous motivation | [43,44,48,52] nonsignificant; [54,61,66,67,68,71,72,73] decrease; [40] no changes in motivation; [78] autonomous motivation for screen time | ||

| Interjected regulation | [42,53,64] decrease; [39] increase Experimental Group; [77] increase | [49,75] increase | |

| External regulation | [64] decrease; [65] decrease; [69] decrease; [77] decrease | ||

| Controlled motivation | [59] increase for dietetic intake | [63] decrease | |

| Amotivation | [22] decrease; [75] increased; [59] increased for PA and dietetic intake; [65,69] increased; [73] increased | [22] increasing; [75] increased; [54] increasing | |

| Basic Need Satisfaction | Competence | [50,51] decrease; [42] in the female gender; [61,73] decrease; [39] decrease tendency; [74,76,77,80] | |

| autonomy | [22,44,50,53] professor; parents and peers [54]; [42] in the female gender; [61,69] support for parents and peers; [73] decrease; [39] no changes; [74,76,77,80] | [53] professor; parents decreased, and peers increased | |

| relatedness | [42,44] female gender; [61,73] decrease; [39] decrease tendency; [74,77,80] | ||

| satisfaction | [22,47] | [22,47] | |

| Basic Need Support | Competence | [42,66] perceived competence; [67,73] decrease; [76] | |

| autonomy | [42,46,58,62] perceived; [67,68,73] decrease; [39,76,77] | ||

| relatedness | [42,67,73] decrease | ||

| Basic Need Frustration | competence | [21,76] decrease; [80] decrease | |

| Autonomy | [76] decrease | ||

| Relatedness | [44,48,76] decrease | ||

| Frustration | [22,47] decrease | [22,47] increase | |

| Achievement Goal Theory | Task-oriented climate | [45,56,58] decrease [60,72] | [57,60] increase |

| Ego-oriented climate | [45,55,56] increase; [72] decrease; [76] decrease | [60] increase | |

| Behaviours | Intention to be physically active | [48,50] decreasing; [53,61,70]; [73] decrease; [76] predisposition towards content; | [48,53] |

| Sedentary | [62,63,64] decrease screen time; | ||

| Lifestyle | [52] healthy intake | ||

| Physical activity | [43,46,51,53,54] PA in the spare time [55,56] decrease; [21,58,60] in the spare time; [61] in the spare time; [62,63] in the spare timeand MVPA; [65,66] during PE classes in the PE control group; [40,68]; [71] decrease [70,77] increase with accelerometers; [79] with smartwatch feed-back calories | [53] increase | |

| Attitude | [23,41,49,50,52] towards PA; [55,68] competition; [64] benefitsperceive; [70] affective andinstrumental attitude; [74] affective; | [23,55] | |

| Effort in PE | [23,42,44] Female; [72] | ||

| Behavioral perceived control | [23] self-control; respect [61] | ||

| Engagement | [22] | ||

| AntropometricVariables | Cardiorrespiratory fitness | [40,51,64] changes showed | |

| BMI/adiposity | [59] increase [64] slightly improved; [40] slightly reduction [39,78] | ||

| PsichosocialVariables | Body image | [40] | |

| Quality life | [69] no changes showed; [40] changes showed; [77] | ||

| Well-being | [43] | ||

| Funny/enjoy | [41,42,48,50,56] decrease, [57] decrease; [65,67,71,72,76] | [41] | |

| boredom | [48] decrease [76] decrease | [48] increased | |

| useldfulness | [42] only in female gender | ||

| self-efficacy | [39,41,44,46,66] | [66] | |

| appearance | [57] | [57] | |

| Psychological condition | [57,74] cognitive activity; [80] support to the cognitive perception | [57] | |

| Perceived barriers | [71] increased | ||

| Subjective norms | [53,61] | [53] | |

| Psychosocial climate | [45,57] affiliation; [76,80] perception of intimidation | ||

| Social support | [71,80] perception of organizational and procedural support | ||

| Prosocial behavior | [47] | [47] | |

| Antisocial behavior | [47] decrease; [76] defiant opposition, decrease | [47] increased |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vaquero-Solís, M.; Gallego, D.I.; Tapia-Serrano, M.Á.; Pulido, J.J.; Sánchez-Miguel, P.A. School-based Physical Activity Interventions in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 999. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030999

Vaquero-Solís M, Gallego DI, Tapia-Serrano MÁ, Pulido JJ, Sánchez-Miguel PA. School-based Physical Activity Interventions in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(3):999. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030999

Chicago/Turabian StyleVaquero-Solís, Mikel, Damián Iglesias Gallego, Miguel Ángel Tapia-Serrano, Juan J. Pulido, and Pedro Antonio Sánchez-Miguel. 2020. "School-based Physical Activity Interventions in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 3: 999. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030999

APA StyleVaquero-Solís, M., Gallego, D. I., Tapia-Serrano, M. Á., Pulido, J. J., & Sánchez-Miguel, P. A. (2020). School-based Physical Activity Interventions in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), 999. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030999