‘We Are Drinking Diseases’: Perception of Water Insecurity and Emotional Distress in Urban Slums in Accra, Ghana

Abstract

1. Introduction

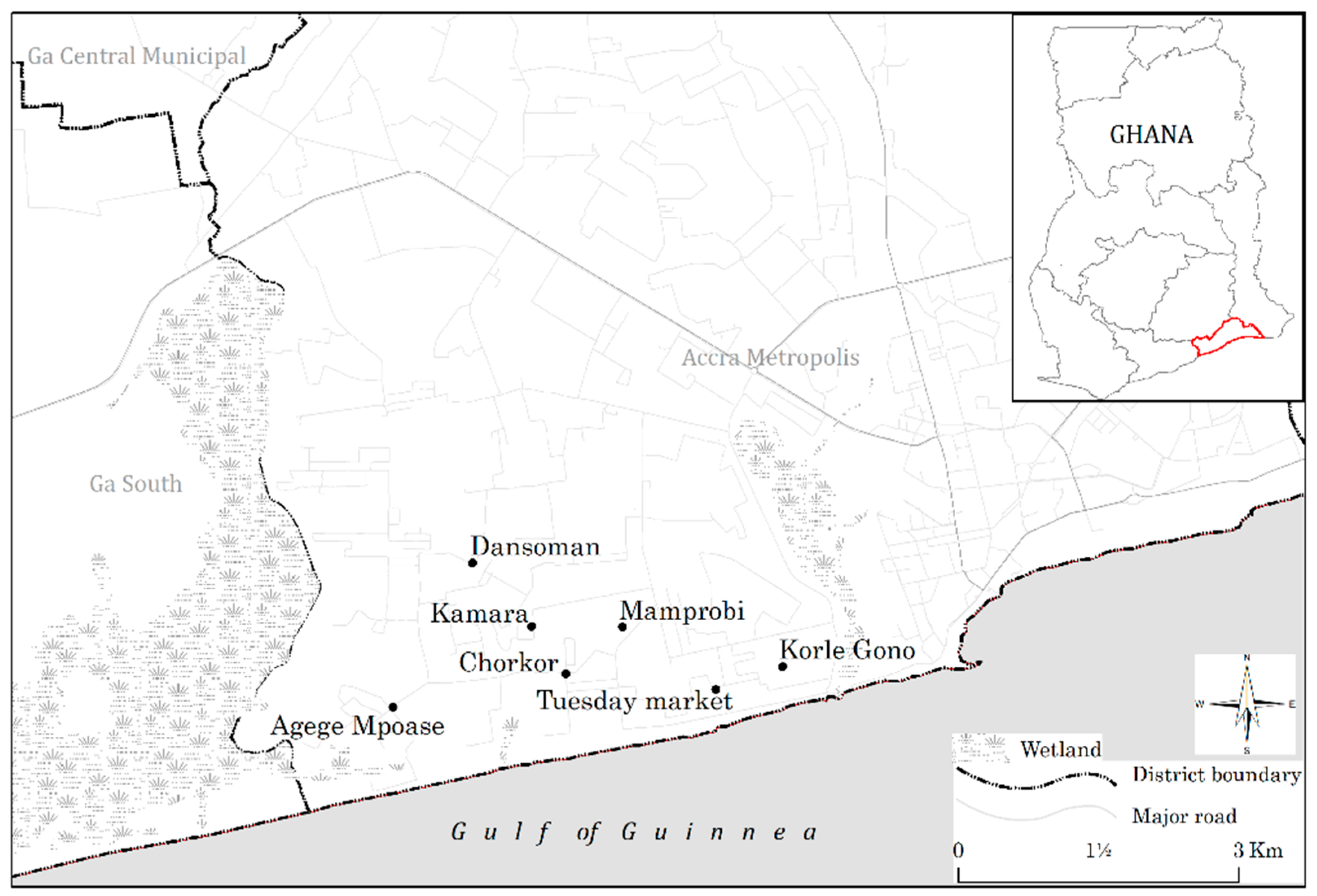

2. Study Context

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Survey

3.2. Measures

4. Analysis

4.1. Household Survey

4.2. Photo-Voice

5. Results

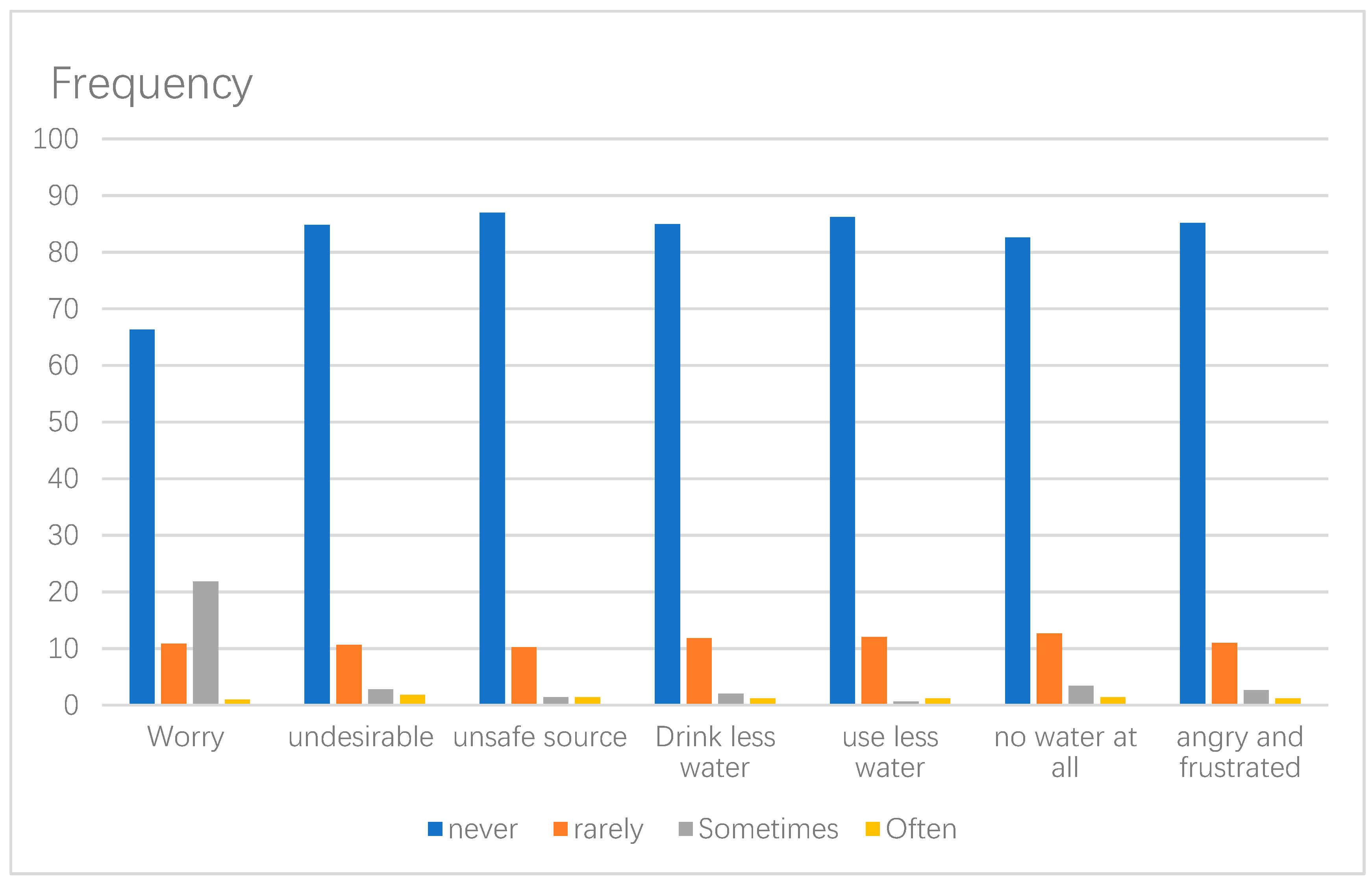

5.1. Quantitative Results

5.2. Bivariate Association between Emotional Distress and Selected Independent Variables

5.3. Multi-Variate Results

5.4. Qualitative Results

5.5. Exposure to Contaminants

The color of water is like black, dark brown, green…you see like a combination of colors …you can’t really tell…and if you let it sit for some time and you look at the bottom, it doesn’t take long and then it becomes slimy. Father Jesus…you can see that people are suffering…like if you put a cup at the end of the pipe and just drink it, you can see that you’ve taken illness …and people in this house do that thing a lot …they just fetch it and use it for tea…can you just imagine…they are just really killing themselves”“…if we want to wash or bath, then we have to let it sit and then when it is clear, before you can use it to bath …otherwise you can’t bath with it because your body aches”

5.6. Disease Burden on Children

“It can give us infection…it can trouble your stomach…also, if you cook with it, it cannot do anything good for you…sometimes, the children…when they fetch and drink the water immediately they complain of stomach ache and we cannot even use the water to wash their feeding bottles …we use pure water to wash the feeding bottles”“…and even in bathing babies…sometimes when we fetch the water and it’s not clean, my mother buys one bag of pure water and then we divide before we use to bath the baby…the nurses told us that if you want to do anything for the baby…you have to get clean and clear water before you do it for the baby”

5.7. Psychosocial Impacts

“The sachet water too I have a problem with it because sometimes when you finish drinking it and you look inside the sachet rubber, you find that it is slippery…yes… If you pass your fingers through it, it feels like okro …eh hee seriously… after drinking, you realized you have drunk diseases”“It bothers me because they are several times when I want water to drink water, I have to drink it with the dirt or wait for it to sit (settle), you realize that there are even metal pieces when you fetch it into a white bucket and wait for some days, you’ll see rusting …rust at the bottom of the container …it shows that the water is not good and I worry all the time”

“There are many houses in which there is no pipe and so they go to fetch from other people who sell the pipe water…those who sell the water, if today they sell at 1GHC …after one month or two they will say their bill has increased and you have to pay higher amounts”“Previously, the water used to be fine, the color was white…but these days they don’t treat the water well (referring to Water vendors and Ghana water company)…because when we fetch the water…you can see that the water is black… brown and others. We have to let the water sit for some time…or you have to go and buy a form (water purifier) before you can drink it”

5.8. Infrastructural Challenges

“we have to make sure that the people working at where the water is, are trained and the metals …they have to look at the metals(water distribution pipes) …the metals may be very old …they need to change them…I think we get our water from Weija …, Weija is my hometown …if you go there and look at some of the metals…they have to do something”

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO/UNICEF. Progress on Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene: 2017 Update and SDG Baselines; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2017/launchversion-report-jmp-water-sanitation-hygiene.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2018).

- Onda, K.; LoBuglio, J.; Bartram, J. Global access to safe water: Accounting for water quality and the resulting impact on MDG progress. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 880–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, A.C.; Kakuhikire, B.; Mushavi, R.; Vořechovská, D.; Perkins, J.M.; McDonough, A.Q.; Bangsberg, D.R. Population-based study of intra-household gender differences in water insecurity: Reliability and validity of a survey instrument for use in rural Uganda. J. Water Health 2015, 14, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Oza, S.; Hogan, D.; Chu, Y.; Perin, J.; Zhu, J.; Black, R.E. Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000–15: An updated systematic analysis with implications for the Sustainable Development Goals. The Lancet 2016, 388, 3027–3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartram, J.; Cairncross, S. Hygiene, sanitation, and water: Forgotten foundations of health. PLoS Med. 2010, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushavi, R.C.; Burns, B.F.; Kakuhikire, B.; Owembabazi, M.; Vořechovská, D.; McDonough, A.Q.; Cooper-Vinceg, C.E.; Bagumaf, C.; Rasmusseneh, J.D.; Bangsberg, D.R.; et al. “When you have no water, it means you have no peace”: A mixed-methods, whole-population study of water insecurity and depression in rural Uganda. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 245, 112561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, S.L.; Boateng, G.O.; Jamaluddine, Z.; Miller, J.D.; Frongillo, E.A.; Neilands, T.B.; Stoler, J. The Household Water InSecurity Experiences (HWISE) Scale: Development and validation of a household water insecurity measure for low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4, e001750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisung, E.; Elliott, S.J.; Abudho, B.; Schuster-Wallace, C.J.; Karanja, D.M. Dreaming of toilets: Using photovoice to explore knowledge, attitudes and practices around water–health linkages in rural Kenya. Health Place 2015, 31, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper-Vince, C.E.; Arachy, H.; Kakuhikire, B.; Vořechovská, D.; Mushavi, R.C.; Baguma, C.; Tsai, A.C. Water insecurity and gendered risk for depression in rural Uganda: A hotspot analysis. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisung, E.; Elliott, S.J. Improvement in access to safe water, household water insecurity, and time savings: A cross-sectional retrospective study in Kenya. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 200, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelnga, H.T.; Ribbe, L.; Frechen, F.B.; Saghir, J. Urban Water Security: Definition and Assessment Framework. Resources 2019, 8, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, C.; Bakker, K. Water security: Debating an emerging paradigm. Glob. Environ. Change 2012, 22, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gober, P.A.; Strickert, G.E.; Clark, D.A.; Chun, K.P.; Payton, D.; Bruce, K. Divergent perspectives on water security: Bridging the policy debate. Prof. Geogr. 2015, 67, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepson, W.E.; Wutich, A.; Colllins, S.M.; Boateng, G.O.; Young, S.L. Progress in household water insecurity metrics: A cross-disciplinary approach. Wires Water 2017, 4, e1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. The World’s Cities in 2016—Data Booklet (ST/ESA/SER.A/392). 2016. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/urbanization/the_worlds_cities_in_2016_data_booklet.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2019).

- Duran-Encalada, J.A.; Paucar-Caceres, A.; Bandala, E.R.; Wright, G.H. The impact of global climate change on water quantity and quality: A system dynamics approach to the US–Mexican transborder region. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2017, 256, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanjra, M.A.; Qureshi, M.E. Global water crisis and future food security in an era of climate change. Food Policy 2010, 35, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, D.; Stoler, J. An Evolving Choice in a Diverse Water Market: A Quality Comparison of Sachet Water with Community and Household Water Sources in Ghana. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2018, 99, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjaya, D.; Tilley, E.; Marks, S.J. Informally Vended Sachet Water: Handling Practices and Microbial Water Quality. Water 2019, 11, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoler, J. The sachet water phenomenon in Accra: Socioeconomic, environmental, and public health implications for water security. In Spatial Inequalities; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherland, 2013; pp. 181–190. [Google Scholar]

- Stoler, J.; Weeks, J.R.; Fink, G. Sachet drinking water in Ghana’s Accra-Tema metropolitan area: Past, present, and future. J. Water Sanitat. Hyg. Dev. 2012, 2, 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghana Statistical Service. 2010 Population and Housing Census Report. Ghana Statistical Service. Available online: https://statsghana.gov.gh/gssmain/storage/img/marqueeupdater/Census2010_Summary_report_of_final_results.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2019).

- Hunter, P.R.; MacDonald, A.M.; Carter, R.C. Water supply and health. PLoS Med. 2010, 7, e1000361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoler, J.; Tutu, R.A.; Winslow, K. Piped water flows but sachet consumption grows: The paradoxical drinking water landscape of an urban slum in Ashaiman, Ghana. Habitat Int. 2015, 47, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workman, C.L.; Ureksoy, H. Water insecurity in a syndemic context: Understanding the psycho-emotional stress of water insecurity in Lesotho, Africa. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 179, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisung, E.; Elliott, S.J. “It makes us really look inferior to outsiders”: Coping with psychosocial experiences associated with the lack of access to safe water and sanitation. Can. J. Public Health 2017, 108, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilhjalmsdottir, A.; Gardarsdottir, R.B.; Bernburg, J.G.; Sigfusdottir, I.D. Neighborhood income inequality, social capital and emotional distress among adolescents: A population-based study. J. Adolesc. 2016, 51, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wutich, A.; Ragsdale, K. Water insecurity and emotional distress: Coping with supply, access, and seasonal variability of water in a Bolivian squatter settlement. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 2116–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, J.; Frongillo, E.A.; Rogers, B.L.; Webb, P.; Wilde, P.E.; Houser, R. Commonalities in the experience of household food insecurity across cultures: What are measures missing? J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 1438S–1448S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadley, C.; Wutich, A. Experience-based Measures of Food and Water Security: Biocultural Approaches to Grounded Measures of Insecurity. Hum. Organ. 2009, 68, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wutich, A.; Brewis, A. Food, water, and scarcity: Toward a broader anthropology of resource insecurity. Curr. Anthropol. 2014, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldin, J.A. Water policy in South Africa: Trust and knowledge as obstacles to reform. Rev. Radic. Polit. Econ. 2010, 42, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, E.G.; Greene, L.E.; Maes, K.C.; Ambelu, A.; Tesfaye, Y.A.; Rheingans, R.; Hadley, C. Water insecurity in 3 dimensions: An anthropological perspective on water and women’s psychosocial distress in Ethiopia. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghana Demographic and Health Surveys. Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/fr307/fr307.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2019).

- Gaisie, S.K.; Gyau-Boakye, P.G. Population growth, water/sanitation and health. In Population, Health and Development in Ghana: Attaining the Millennium Development Goals; Mba, C.J., Kwankye, S.O., Eds.; Sub-Saharan Publishers: Accra, Ghana, 2007; pp. 91–134. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Program. Human Development Report 2006, Beyond Scarcity: Power, Poverty and Global Water Crisis; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Coates, J.; Swindale, A.; Bilinsky, P. Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for Measurement of Food Access: Indicator Guide; Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project; Academy for Educational Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Coates, J. Build it back better: Deconstructing food security for improved measurement and action. Glob. Food Sec. 2013, 2, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swindale, A.; Bilinsky, P. Development of a universally applicable household food insecurity measurement tool: Process, current status, and outstanding issues. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 1449S–1452S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, D.; Vaitla, B.; Coates, J. How do indicators of household food insecurity measure up? An empirical comparison from Ethiopia. Food Policy 2014, 47, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinstrup-Andersen, P. Food security: Definition and measurement. Food Secur. 2009, 1, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO and USAID. Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for Measurement of Food Access. Available online: http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/eufao-fsi4dm/doc-training/hfias.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2019).

- WHO: Guidelines For Drinking-Water Quality. Available online: https://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/dwq/gdwqvol32ed.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2019).

- Doria, M.F. Bottled water versus tap water: Understanding consumers’ preferences. J. Water Health 2006, 4, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, J.A.; Yang, H.; Rivett, U.; Gundry, S.W. Public perception of drinking water safety in South Africa 2002–2009: A repeated cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutstein, S.; Johnson, K. The DHS Wealth Index; ORC Macro, MEASURE DHS+: Calverton, MD, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Grieb, S.D.; Smith, K.C.; Calhoun, K.; Tandon, D. Qualitative research and community-based participatory research: Considerations for effective dissemination in the peer-reviewed literature. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2015, 9, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Burris, M.A. Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ. Behav. 1997, 24, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Burris, M. Empowerment through Photo Novella: Portraits of Participation. Health Educ. Q. 1994, 21, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, G. Engendering the slum: Photography in East London in the 1930s. Gend. Place Cult. 1997, 4, 277–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabe-Hesketh, S.; Skrondal, A. Multilevel and Longitudinal Modeling Using Stata; STATA Press: College Station, TX, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schielzeth, H.; Nakagawa, S. Nested by design: Model fitting and interpretation in a mixed model era. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2013, 4, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S.; Ullman, J.B. Using Multivariate Statistics; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2007; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Ennis-McMillan, M.C. Suffering from water: Social origins of bodily distress in a Mexican community. Med. Anthropol. Q. 2001, 15, 368–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wutich, A. The moral economy of water reexamined: Reciprocity, water insecurity, and urban survival in Cochabamba, Bolivia. J. Anthropol. Stud. 2011, 67, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wutich, A.; Beresford, M.; Carvajal, C. Can informal water vendors deliver on the promise of a human right to water? Results from Cochabamba, Bolivia. World Dev. 2016, 79, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimani-Murage, E.W.; Schofield, L.; Wekesah, F.; Mohamed, S.; Mberu, B.; Ettarh, R.; Ezeh, A. Vulnerability to food insecurity in urban slums: Experiences from Nairobi, Kenya. J. Urban Health 2014, 91, 1098–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutu, R.A.; Stoler, J. Urban but off the grid: The struggle for water in two urban slums in greater Accra, Ghana. African Geogr. Rev. 2016, 35, 212–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, E.A. Thirsty slums in African cities: Household water insecurity in urban informal settlements of Lilongwe, Malawi. Int. J. Water. Resour. Dev. 2018, 34, 869–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisung, E.; Elliott, S.J. Psychosocial impacts of the lack of access to water and sanitation in low-and middle-income countries: A scoping review. J. Water Health 2016, 15, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.M.; Kleiber, D.; Rodina, L.; Yaylaci, S.; Goldin, J.; Owen, G. Water Materialities and citizen engagement: Testing the implications of water access and quality for community engagement in Ghana and South Africa. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2018, 31, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolstad, A.; Gjesvik, N. Collectivism, individualism, and pragmatism in China: Implications for perceptions of mental health. Transcult. Psychiatry 2014, 51, 264–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo, G.A.; Ellison, C.G.; Xu, X. Is it really religion? Comparing the main and stress-buffering effects of religious and secular civic engagement on psychological distress. Soc. Mental Health 2014, 4, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carissoli, C.; Villani, D.; Riva, G. Does a meditation protocol supported by a mobile application help people reduce stress? Suggestions from a controlled pragmatic trial. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2015, 18, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulled, N. The effects of water insecurity and emotional distress on civic action for improved water infrastructure in rural South Africa. Med. Anthropol. Q. 2017, 31, 133–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Independent Variables | Greater Accra |

|---|---|

| Frequency (%) | |

| Emotional distress | |

| None | 353 (72.63) |

| One or more | 133 (27.37) |

| Water security | |

| Secure | 290 (58.12) |

| Insecure | 209 (41.88) |

| Perception of water quality | |

| Wholesome | 261 (52.30) |

| Unwholesome | 238 (47.70) |

| Main source of drinking water | |

| Sachet/bottle | 425 (85.14) |

| Others | 74 (14.83) |

| Distance to collect water (mean) | 16.14 (0–100) |

| Average amount spent daily on water (Ghana Cedis) | 2.80 (0.2–50) |

| Perception of water quality | |

| Unwholesome | 261 (52.30) |

| Wholesome | 238 (47.70) |

| Adequate water for household needs | |

| Inadequate | 146 (29.26) |

| Adequate | 353 (70.74) |

| Sanitation facility | |

| Unimproved | 341 (68.34) |

| Improved | 158 (31.66) |

| Willingness to pay for community water interventions | |

| Unlikely | 352 (70.54) |

| Likely | 147 (29.46) |

| Household food security | |

| Secure | 185 (37.07) |

| Insecure | 314 (62.93) |

| Household wealth level | |

| Poor | 107 (21.44) |

| Middle | 129 (25.85) |

| Rich | 100 (20.04) |

| Richer | 70 (14.03) |

| Richest | 93 (18.64) |

| Education level | |

| None | 71 (14.23) |

| Primary | 106 (21.24) |

| Secondary | 215 (43.09) |

| Tertiary | 107 (21.44) |

| Sexual | |

| Male | 255 (51.10) |

| Female | 244 (48.90) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 188 (37.68) |

| Separated | 61 (12.22) |

| Married | 250 (50.10) |

| Household size (mean) | 2[1–18] |

| Number of girls under 18 in the household (mean) | 1[0–10] |

| Number of boys in the household (mean) | 1[0–12] |

| Number of adult women in the household (mean) | 2[1–17] |

| Number of adult men in the household (mean) | 2[1–17] |

| Neighborhoods of residence | |

| Agege-Manponse | 60 (12.02) |

| Chorkor | 157 (31.46) |

| Dansoman | 58 (11.62) |

| Korle Gonno | 166 (88.38) |

| Other | 58 (11.62) |

| Observations | 499 |

| Independent Variables | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Water insecurity (ref: secure) | |

| Insecure | 1.90 (1.22–2.95) *** |

| Main source of drinking water (ref: sachet or bottle) | |

| Others | 2.10 (1.24–3.55 *** |

| Distance to collect water | 1.01 (1.000–1.012) * |

| Amount spent | 0.92 (0.82–1.03) |

| Quantity of water (ref: inadequate) | |

| Adequate | 1.62 (1.01–2.61) ** |

| Perception of water quality (ref: wholesome) | |

| Unwholesome | 1.71 (1.06–2.74) ** |

| Access to sanitation (ref: unimproved) | |

| Improved | 0.26 (0.15–0.47) *** |

| Willingness to pay for community water interventions (ref: unlikely) | |

| Likely | 0.27 (0.16–0.47) *** |

| Household food security status (ref: secure) | |

| Insecure | 1.53 (0.98–2.39) * |

| Household wealth level (ref: poor) | |

| Middle | 1.69 (0.94–3.03) * |

| Rich | 1.32 (0.68–2.55) |

| Richer | 1.28 (0.63–2.60) |

| Richest | 0.71 (0.35–1.43) |

| Educational level (ref: none) | |

| Primary | 0.55 (0.28–1.08) * |

| Secondary | 0.27 (0.15–0.51) *** |

| Tertiary | 0.28 (0.14–0.59) *** |

| Sex (ref: male) | |

| Female | 0.92 (0.61–1.39) |

| Marital status (ref: single) | |

| Separated | 0.72 (0.36–1.43) |

| Married | 0.72 (0.45–1.16) |

| Household type (ref: Nuclear) | |

| Extended family | 0.93 (0.57–1.51) |

| Number of Household members | 1.07 (0.96–1.19) |

| Number of girls under 18 in the household | 1.15 (0.99–1.34) * |

| Number of boys under 18 in the household | 1.22 (1.05–1.42) *** |

| Observations | 499 |

| Independent Variables | Model 1 OR(SE) | Model 2 OR(SE) |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional Distress | Emotional Distress | |

| Water insecurity (ref: secure) | ||

| Insecure | 1.78 (1.04–3.04) ** | 2.24 (1.25–4.01) *** |

| Main source of drinking water (ref: sachet or bottle) | ||

| Other | 1.60 (0.91–2.82) | 1.29 (0.69–2.41) |

| Distance to collect water | 1.01 (1.00–1.01) * | 1.01 (0.99–1.01) * |

| Amount spent | 0.94 (0.84–1.06) | 0.96 (0.87–1.07) |

| Quantity of water (ref: inadequate) | ||

| Adequate | 0.89 (0.51–1.58) | 1.13 (0.61–2.12) |

| Perception of water quality (ref: wholesome) | ||

| Unwholesome | 2.49 (1.48–4.19) *** | 2.23 (1.27–3.93) *** |

| Access to sanitation (ref: unimproved) | ||

| Improved | 0.28 (0.16–0.50) *** | 0.29 (0.15–0.54) *** |

| Willingness to pay for community water interventions (ref: unlikely) | ||

| Likely | 0.28 (0.16–0.51) *** | 0.28 (0.15–0.53) *** |

| Household food security status (ref: secure) | ||

| Insecure | 1.43 (0.85–2.43) | |

| Household wealth level (ref: poor) | ||

| Middle | 3.55 (1.77–7.12) *** | |

| Rich | 2.24 (1.04–4.85) ** | |

| Richer | 2.64 (1.15–6.08) ** | |

| Richest | 2.05 (0.87–4.81) * | |

| Educational level (ref: none) | ||

| Primary | 0.64 (0.31–1.35) | |

| Secondary | 0.33 (0.16–0.67) *** | |

| Tertiary | 0.51 (0.22–1.17) | |

| Sex (ref: male) | ||

| Female | 1.02 (0.630–1.661) | |

| Marital status (ref: single) | ||

| Separated | 0.44 (0.19–0.97) ** | |

| Married | 0.50 (0.28–0.87) ** | |

| Household type (ref: Nuclear) | ||

| Extended family | 0.92 (0.50–1.67) | |

| Household number | 0.94 (0.76–1.17) | |

| Number of boys under 18 | 1.24 (0.95–1.61) | |

| Number of boys under 18 | 0.98 (0.76–1.28) | |

| Random effects | ||

| Neighborhood | 1.00 (0.73–1.36) | 1.00 (0.72–1.38) |

| Constant | 0.32 (0.16–0.66) *** | 0.31 (0.08–1.15) * |

| Observations | 499 | |

| Impacts | # of photographs (n = 30) |

|---|---|

| Exposure to contaminants | 10 |

| Disease burden on children | 6 |

| Psychosocial health | 10 |

| Infrastructural challenges | 4 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kangmennaang, J.; Bisung, E.; Elliott, S.J. ‘We Are Drinking Diseases’: Perception of Water Insecurity and Emotional Distress in Urban Slums in Accra, Ghana. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 890. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030890

Kangmennaang J, Bisung E, Elliott SJ. ‘We Are Drinking Diseases’: Perception of Water Insecurity and Emotional Distress in Urban Slums in Accra, Ghana. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(3):890. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030890

Chicago/Turabian StyleKangmennaang, Joseph, Elijah Bisung, and Susan J. Elliott. 2020. "‘We Are Drinking Diseases’: Perception of Water Insecurity and Emotional Distress in Urban Slums in Accra, Ghana" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 3: 890. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030890

APA StyleKangmennaang, J., Bisung, E., & Elliott, S. J. (2020). ‘We Are Drinking Diseases’: Perception of Water Insecurity and Emotional Distress in Urban Slums in Accra, Ghana. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), 890. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030890