Parents’ Experiences of the First Year at Home with an Infant Born Extremely Preterm with and without Post-Discharge Intervention: Ambivalence, Loneliness, and Relationship Impact

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Parental Mental Health Following Premature Birth

1.2. The Inner Parental Experience of Preterm Birth

1.3. Preterm Birth Affecting Interaction and Attachment

1.4. Theoretical Approach and Previous Evidence of Home-Visiting Programs

1.5. Theoretical Approach of Health and Development

1.6. Aim

- (I).

- How do parents of children born EPT describe the first year at home post-discharge?

- (II).

- How is participating in an interaction- and strength-based home-visiting program perceived by parents of children born EPT?

2. Materials and Methods

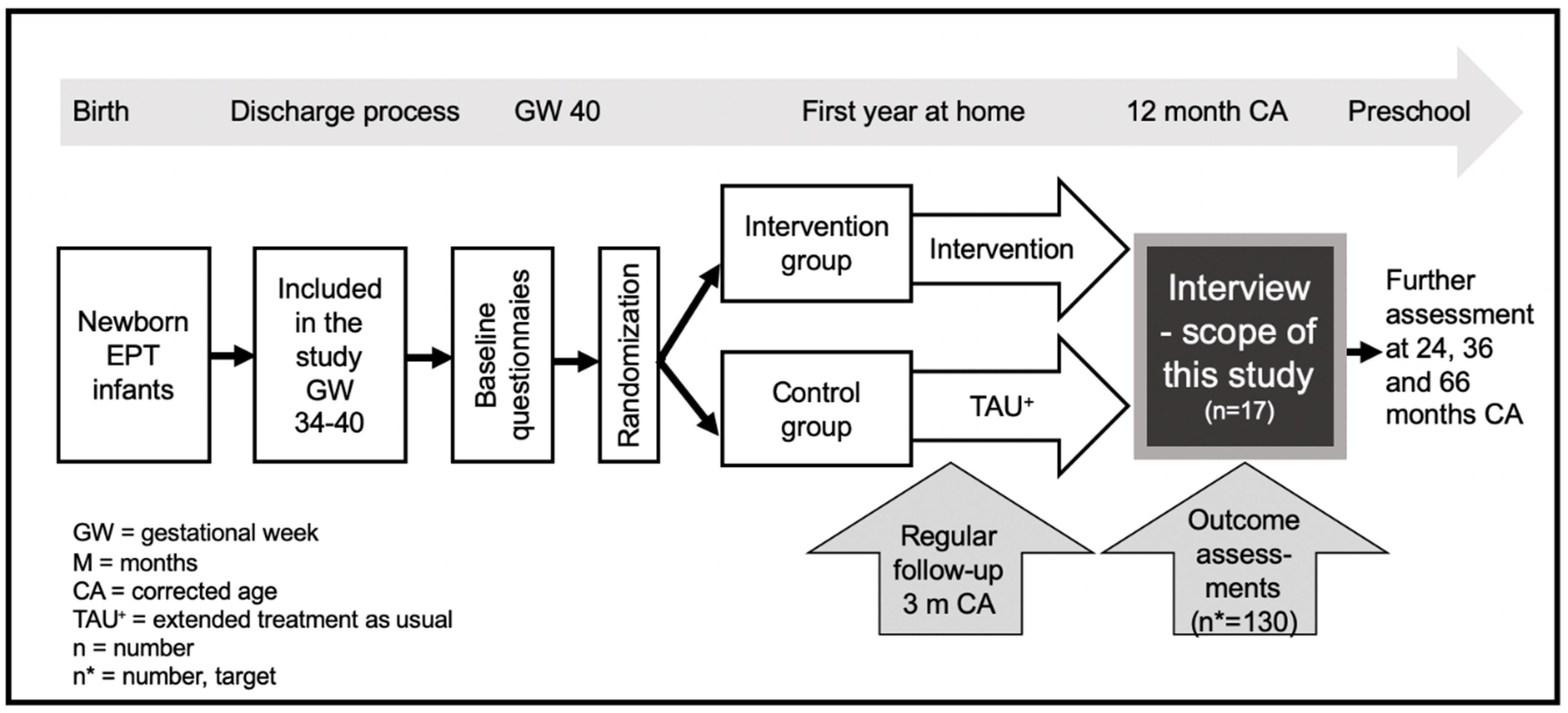

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Treatment as Usual (TAU)

2.4. The Intervention

2.5. Two Semi-Structured Interview Guides

2.6. Procedure

2.7. Ethical Considerations

2.8. Thematic Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The First Year at Home, Regardless of Group (Answering Research Question I)

3.1.1. Main Theme 1: Child-Related Concerns

Subtheme: Continued Medical Concerns

Subtheme: Child Regulation and Body Functions

Subtheme: Incomplete Recovery When Coming Home

He had a cold at discharge, he received it in the neonatal unit, it’s written in the medical record that they suctioned his nose [of mucus], you know, some day before we went home. Everybody knew that he had a cold. But the cold got worse, that is the first thing I say to her [the neonatal visiting nurse] when she comes, “how are you?” and I answer “he has a bit of a cold”. And then I take him in my arms, and it is like holding your [pause] dead child. He is… completely lifeless. And totally grey, I still almost cannot talk about it. [Interviewer: even if it is one year ago?] Yes. So… eh… we try to get him back to life and then I leave him to her [the neonatal visiting nurse] and she makes him inhale…he is breathing a bit, and she says “no, you have to call 911”.(N, mother from TAU+)

We were home for maybe one and a half days, and we noticed that [infant name] lost her muscular tone, which was a little longer, so we called and they transferred us to [name of hospital], where we came from [name of another hospital], so we called and they said we should go there, and we had to stay another week. They were a bit upset with [name of hospital] that they had sent us home so early, that it was completely, well, one doctor was very angry, thought it was too early. It is enormously stressful to come home and see that she did not cope with it. And, then, she received oxygen for one more week and they discussed oxygen at discharge.(L, mother from TAU+)

3.1.2. Main Theme 2: Parental Inner State

Subtheme: Loneliness

So, just to meet other people, during wintertime when we came home, there were many infections around, so just telling people “you may not lift, not caress, you may not… keep away, you may look—but not touch. I think it is very hard for many people to understand, just that tiny part, you may look but do not touch. Because everybody says “oh, a baby”, [approaching body language] it is something imprinted in this…(H, mother from IG)

Well my husband, he helps a lot, but when it comes to hospitals, he cannot handle…he thinks, he cannot handle the hospital environment for example. So, it has been tough for me, because I lived there for two and a half months. Many parents took turns, and that was ’what I missed the most. You have to take turns, because it’s just not possible.(G, mother from IG)

I found it [the SPIBI-intervention] very rewarding and it has given me security, so I found it very good. We did not have any home care, for us it was quite abrupt because he was fully breastfed and had no oxygen supply when we came home around term age, so for us we went from meticulous monitoring, to practically not speaking. So, we were lucky to be a part of the study and have [interventionist name] coming to our home.(I, mother from IG)

Subtheme: Ambivalence

It’s the first time he leaves the hospital, tastes air, sits in a chair or a baby car seat. Those were some tough hours. Yes. When he came home, we called the nurse and asked why his saturation was so low. Turns out, he had been sitting like this [shows crouched position] in the baby car seat and had not been getting enough air, so he was tired. So, when we arrived home, it took more time than we expected, maybe an hour./…/He was so tired, he could not even poop. And for us it was like “not today—not when we just arrived home”.(D, mother from TAU+)

But, when that day came [the one-year corrected age birthday], then one felt a bit guilty. Because when we speak with this group, they wrote, they said that they lost one of the twins, so it has been tough for her, he died in the womb. And the other, I think she had some anxiety before, so, they have felt really bad.(G, mother from IG)

Subtheme: Preterm Parental Identity

So, it’s a bit scary, like it feels like we have now distanced ourselves from that [the extreme preterm birth] then maybe you should not stick in this [Facebook group] flow of the process. So, the thought has struck me if I should sort of leave that group, because we are trying to let it go now. Because you always hear… there are a lot of problems in these kinds of groups as well, how people air their concerns./…/Or it’s something that makes me hang in there [in the Facebook group], a little. Still. For some reason.(F, mother from TAU+)

I cannot relate her to her early birth any longer. But when I see the photos in my phone, that I took [in the hospital] at that time, then I feel “has that happened to me?” One forgets so fast and that is good, in one way, I think, because it has been OK, she is here and growing. Why should I go back and dwell upon what has been when there is no point?(K, mother from TAU+)

3.1.3. Main Theme 3: Changed Family Dynamics

Subtheme: The Parental Dyad

Yes, but then he went back to work in March, yeah, so he stayed home a bit longer. Uhm, but then I felt… I felt quite bad mentally during spring, I felt extremely stressed, like I was approaching fatigue depression, everything stressed me out, just visiting the well-baby clinic [BVC] was stressful. I don’t know if it was, that so many things that caught up from the past time, or the shock of becoming parent of two children, which was much tougher than I ever imagined. Or if it was interconnected.(F, mother of TAU+)

And then when we change TPN [total parenteral nutrition], from the beginning we said that I changed one time, then my husband changed the next. But his, you know, men are not so careful as women are, or not so [pause] skilled as women. So, I just told him “you have to do it like this” and he got very angry, because he thought I was saying I was more capable than he was. It’s not like I don’t believe in him, even if that is what he thinks. But, the first period, it was about how we fed him, how we gave him medicine, replaced the tube. It was a bit tense at times, during that period.(J, mother from TAU+)

It is incredibly stressful to come home and like try to handle that you are coming home with a newborn, but also somebody that fragile, and then I was eh… more or less all alone in this situation from discharge/…/At the hospital, that was at [name of hospital], we were, there were so many staff members that came to us and were fascinated by how nicely we handled it together and that was my experience too. But then, as I said before, when we came home… then… well it was a personality change, absolutely.(L, mother from TAU+)

Well, we, it felt like we are persons who “We will be fine, we’ll be fine, we do not need anybody”. But this time I felt more like “no, we will not be fine—we need help” and there is nothing wrong in asking for help.(M, mother from IG)

Subtheme: Thoughts Relating to Siblings

Subtheme: Intergenerational Support

So, in that way we have had the support that somebody, if I regained lost sleep, the first week my mother lived with us and then I could sleep while he was awake with my mother. So, because she is not updated in his [medical state], but just to cook, clean, and everything. And then the second week, his [the father’s] mother came and lived with us and did the same thing.(D mother from TAU+)

3.2. Specific Themes Connected to the Intervention, Answering Research Question II

It was in three parts, so in the beginning I felt that [name of interventionist] was like a psychologist almost, just so you feel that…You have had psychological support/…/And then it is a bit like a physiotherapist, she has coached me a lot, like “he will soon start with this, so do this”/…/and then the food, when one has been forever worried, that we could discuss that a bit.(I, mother from IG)

3.2.1. Intervention Group (IG)-Theme 1: Security

More home-visits maybe. Sitting talking, like we do now. How it works at home, if it is something we need… But when we came home, it was all over, it was just me going there all the time because of the [child’s] constipation. Nobody came. I asked somebody there when I was worried that it will be a tough situation at home. They said ”no, you don’t need home care because he does not have a tube or anything”/…/but still, he was not very…very strong/…/but you know, the worry is stuck here [points to her heart].(A mother from TAU+)

3.2.2. IG-Theme 2: Knowledgeable Interventionist

I think it gave me quite a lot, regarding that, eh, I learned to think in another way, it opened my eyes, I had an “Aha-moment”, for example things that you take for granted, you think he does not understand, but all of a sudden, “oops, he understands”.(M, mother from IG)

It has not always been us posing questions, more that she mentions or says this is common amongst preterm born, or extremely preterm born … and maybe you have not thought of that at the time, but then when you compare to other children, or what shall I say, at some point, then you are not like “but why does my child don’t do that”, because she has prevented that worry.(H, mother from IG)

It was very fun to be able to participate, really, when [name of interventionist] came and gave tips and suggested what to do, things I did not think of with my previous children, “aha, that is why they do that, it is for this reason.(G, mother from IG)

It was good, because as [name of child] is our first child, we did not know much about parenting, so when [name of interventionist] came and said “she’s going to do this thing in a few days, a few weeks” it was helpful for us.(E, father from IG)

3.2.3. IG-Theme 3: Important, but Not Necessary

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blencowe, H.; Cousens, S.; Chou, D.; Oestergaard, M.; Say, L.; Moller, A.B.; Kinney, M.; Lawn, J. Born too soon: The global epidemiology of 15 million preterm births. Reprod. Health 2013, 10 (Suppl. S1), S2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- March of Dimes; PMNCH; Save the Children; WHO. Born Too Soon: The Global Action Report on Preterm Birth; Howson, C.P., Kinney, M.V., Lawn, J.E., Eds.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cnattingius, S.; Ericson, A.; Gunnarskog, J.; Källén, B. A quality study of a medical birth registry. Scand. J. Soc. Med. 1990, 18, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, D.; Stein, M.T. Intensive Parenting: Surviving the Emotional Journey through the NICU; Fulcrum Publishing: Wheat Ridge, CO, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kleberg, A.; Helltröm-Westas, L.; Widström, A.M. Mothers’ perceptions of Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program (NIDCAP) as compared to conventional care. Early Hum. Dev. 2007, 83, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleberg, A.; Westrup, B.; Stjernqvist, K.; Lagercrantz, H. Indications of improved cognitive development at one year of age among infants born very prematurely who received care based on the Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program (NIDCAP). Early Hum. Dev. 2002, 68, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westrup, B. Family-centered developmentally supportive care: The Swedish example. Arch. Pediatr. 2015, 22, 1086–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solhaug, M.; Bjork, I.T.; Sandtro, H.P. Staff Perception one year after Implementation of the Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment program (NIDCAP). J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2010, 25, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirlashari, J.; Brown, H.; Fomani, K.F.; de Salaberry, J.; Khanmohamad, Z.; Khoshkhou, F. The challenges of implementing family, centered care in NICU from Perspectives of Physicians and nurses. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2020, 50, e91–e98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raiskila, S.; Lehtonen, L.; Tandberg, B.S.; Normann, E.; Ewald, U.; Caballero, S.; Varendi, H.; Toome, L.; Nordhos, M.; Hallberg, B.; et al. Parent and nurse perceptions on the quality of family-centered care in 11 European NICUs. Aust. Crit. Care 2016, 29, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Als, H. Toward a synactive theory of development: Promise for the assessment and support of infant individuality. Infant Ment. Health J. 1982, 3, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Als, H. Newborn individualized developmental care and assessment program (NIDCAP): New frontier for neonatal and perinatal medicine. J. Neonatal-Perinat. Med. 2009, 2, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wielenga, J.M.; Smit, B.J.; Unk, L.K.A. How satisfied are parents supported by nurses with the NIDCAP model of care for their preterm infant? J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2006, 21, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kleberg, A.; Westrup, B.; Stjernqvist, K. Developmental outcome, child behavior and mother-child interaction at 3 years of age following Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Intervention Program (NIDCAP) intervention. Early Hum. Dev. 2000, 60, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westrup, B.; Stjernquist, K.; Kleberg, A.; Hellström-Westas, L.; Lagercrantz, H. Neonatal individualized care in practice: A Swedish experience. Semin. Neonatol. 2002, 7, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, S.E.; Sokol, J.; Ohlsson, A. The newborn individualized developmental care and assessment program is not supported by meta-analyzes of the data. J. Pediatr. 2002, 140, 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlsson, A.; Jacobs, S.E. NIDCAP: A systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. Pediatrics 2013, 131, e881–e893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holditch-Davis, D.; Bartlett, T.R.; Blickman, A.L.; Miles, M.S. Posttraumatic stress symptoms in mothers of premature infants. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2003, 32, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holditch-Davis, D.; Santos, H.; Levy, J.; White-Traut, R.; O’Shea, T.M.; Geraldo, V.; David, R. Patterns of psychological distress in mothers of preterm infants. Infant Behav. Dev. 2015, 41, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.P.; Cui, Y.; Qiu, Y.F.; Han, S.P.; Yu, Z.B.; Guo, X.R. Anxiety and depression in parents of sick neonates: A hospital-based study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2013, 22, 1163–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, L.T.; Salvator, A.; Guo, S.; Collin, M.; Lilien, L.; Baley, J. Maternal psychological distress and parenting stress after the birth of a very low-birth-weight infant. JAMA 1999, 281, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huhtala, M.; Korja, R.; Lehtonen, L.; Haataja, L.; Lapinleimu, H.; Munck, P.; Rautava, P.; The PIPARI Study Group. Parental psychological well-being and cognitive development of very low birth weight infants at 2 years. Acta Paediatr. 2011, 100, 1555–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huhtala, M.; Korja, R.; Lehtonen, L.; Haataja, L.; Lapinleimu, H.; Rautava, P. Associations between parental psychological well-being and socio-emotional development in 5-year-old preterm children. Early Hum. Dev. 2014, 90, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleine, I.; Falconer, S.; Roth, S.; Counsell, S.J.; Redshaw, M.; Kennea, N.; Edwards, A.D.; Nosarti, C. Early postnatal maternal trait anxiety is associated with the behavioral outcomes of children born preterm <33 weeks. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 131, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vigod, S.N.; Villegas, L.; Dennis, C.L.; Ross, L.E. Prevalence and risk factors for postpartum depression among women with preterm and low-birth-weight infants: A systematic review. BJOG 2010, 117, 540–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pace, C.C.; Anderson, P.J.; Lee, K.J.; Spittle, A.J.; Treyvaud, K. Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms in mothers and fathers of very preterm infants overt the first 2 years. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2020, 41, 612–618. [Google Scholar]

- Trombini, E.; Surcinelli, P.; Piccioni, A.; Alessandroni, R.; Faldella, G. Environmental factors associated with stress in mothers of preterm newborns. Acta Paediatr. 2008, 97, 894–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sloan, K.; Rowe, J.; Jones, L. Stress and coping in fathers following the birth of a preterm infant. J. Neonatal Nurs. 2008, 14, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schappin, R.; Wijnroks, L.; Uniken Venema, M.M.A.T.; Jongmans, M.J. Rethinking stress in parents of preterm infants: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, M.; Poehlmann, J.; Bolt, D. Predictors of parenting stress trajectories in premature infant–mother dyads. J. Fam. Psychol. 2013, 27, 873–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmöker, A.; Flacking, R.; Udo, C.; Eriksson, M.; Hellström-Westas, L.; Ericson, J. Longitudinal cohort study reveals different patterns of stress in parents of preterm infants during the first year after birth. Acta Paediatr. 2020, 109, 1778–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serlachius, A.; Hames, J.; Juth, V.; Garton, D.; Rowley, S.; Petrie, K.J. Parental experiences of family-centered care from admission to discharge in the neonatal intensive care unit. J. Pediatr. Child Health 2018, 54, 1227–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, S.; Ray, R.A.; Larkins, S.; Woodward, L. Perspectives of time: A qualitative study of the experiences of parents of critically ill newborns in the neonatal nursery in North Queensland interviewed several years after the admission. Br. Med. J. Open 2019, 9, e026344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Zhang, J.; Yuan, L. Chinese Parents’ Lived Experiences of having Preterm Infants in NICU: A Qualitative Study. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2020, 50, e48–e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abuidhail, J.; Al-Motlaq, M.; Mrayan, L.; Salameh, T. The lived experience of Jordanian Parents in a neonatal intensive care unit: A phenomenological study. J. Nurs. Res. 2017, 25, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widding, U.; Farooqi, A. I thought he was ugly: Mothers of extremely premature children narrate their experiences as troubled subjects. Fem. Psychol. 2016, 26, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, V.C.; Steelfisher, G.K.; Salhi, C.; Shen, L. Coping with the neonatal intensive care unit experience: Parents’ strategies and views of staff support. J. Perinat. Neonatal Nurs. 2012, 26, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, K.; Ternestedt, B.M.; Schollin, J. From alienation to familiarity: Experiences of mothers and fathers of preterm infants. J. Adv. Nurs. 2003, 43, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boykova, M. Life after discharge: What parents of preterm infants say about their transition to home. Newborn Infant Nurs. Rev. 2016, 16, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, J.E.; Tschudy, M.M.; Hussey-Gardner, B.; Jennings, J.M.; Boss, R.D. “I don’t know what I was expecting”: Home visits by neonatology fellows for infants discharged from the NICU. Birth 2017, 44, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damhuis, G.; König, K.; Westrup, B.; Kuhn, P.; Daly, M.; Bertoncelli, N.; Casper, C.; Lilliesköld, S. European Standards of Care for Newborn Health: Case Management and Transition to Home. Available online: https://newborn-health-standards.org/case-management-transition-home/ (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Porat-Zyman, G.; Taubman–Ben-Ari, O.; Kuint, J.; Morag, I. Personal Growth 4 Years after Premature Childbirth: The Role of Change in Maternal Mental Health. J. Happiness Stud. 2019, 20, 1739–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss, 1; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth, M.D.; Wittig, B.A. Attachment and the expletory behavior of one-year-olds in a strange situation. In Determinants of Infant Behavior; Foss, B.M., Ed.; Methuen: London, UK, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. A Secure Base: Parent-Child Attachment and Healthy Human Development; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth, M.D.S.; Blehar, M.C.; Waters, E.; Wall, S. Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation; Lawence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, MI, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Maestro, M.; Sierra-Garcia, P.; Diaz-Gonzalez, C.; Torres-Valdivieso, M.J.; Lora-Pablos, D.; Agres-Segura, S.; Pallas-Alonso, R. Quality of attachment in infants less than 1500g or 32 weeks. Related factors. Early Hum. Dev. 2017, 104, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korja, R.; Latva, R.; Lehtonen, L. The effects of preterm birth on mother-infant interaction and attachment during the infant’s first two years. Acta Obs. Gynecol. Scand. 2012, 91, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navne, L.E.; Svendsen, M.N.; Gammeltoft, T.M. The Attachment Imperative: Parental Experiences of Relation-making in a Danish Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Med. Anthropol. Q. 2018, 32, 120–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina, I.M.F.; Granero-Molina, J.; Fernández-Sola, C.; Hernández-Padilla, J.M.; Ávila, M.C.; Rodríguez, M.D.M.L. Bonding in neonatal intensive care units: Experiences of extremely preterm infants’ mothers. Women Birth 2018, 31, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shonkoff, J.P.; Garner, A.S.; Siegel, B.S.; Dobbins, M.I.; Earls, M.F.; Macguinn, L.; Pascoe, J.; Wood, D.L. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics 2012, 129, e232–e246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckman, J.J. Skill formation and the economics of investing in disadvantaged children. Science 2006, 312, 1900–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finello, K.M.; Terteryan, A.; Riewerts, R.J. Home Visiting Programs: What the Primary Care Clinician Should Know. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 2016, 46, 101–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchon, B.; Gibbs, D.; Harniess, P.; Jary, S.; Crossley, S.; Moffat, J.V.; Basu, A.P. Early intervention programs for infants at high risk of atypical neurodevelopmental outcome. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2019, 61, 1362–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treyvaud, K.; Anderson, V.A.; Howard, K.; Bear, M.; Hunt, R.W.; Doyle, L.W.; Inder, T.E.; Woodward, L.; Anderson, P.J. Parenting Behavior is associated with the early neurobehavioral development of very preterm children. Pediatrics 2009, 123, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flierman, M.; Koldewijn, K.; Meijssen, D.; van Wassenaer-Leemhuis, A.; Aarnoudse-Moens, C.; van Schie, P.; Jeukens-Visser, M. Feasibility of a Preventive Parenting Intervention for Very Preterm Children at 18 Months Corrected Age: A Randomized Pilot Trial. J. Paediatr. 2016, 176, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koldewijn, K.; van Wassenaer, A.; Wolf, M.-J.; Meijssen, D.; Houtzager, B.; Beelen, A.; Kok, J.; Nollet, F. A neurobehavioral intervention and assessment program in very low birth weight infants: Outcome at 24 months. J. Paediatr. 2010, 156, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koldewijn, K.; Wolf, M.J.; van Wassenaer, A.; Meijssen, D.; van Sonderen, L.; van Baar, A.; Beelen, A.; Nollet, F.; Kok, J. The infant behavioural assessment and intervention program for very low birth weight infants at 6 months corrected age. J. Paediatr. 2009, 154, 33–38.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newnham, C.A.; Milgrom, J.; Skouteris, H. Effectiveness of a modified mother–infant transaction program on outcomes for preterm infants from 3 to 24 months of age. Infant Behav. Dev. 2009, 32, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks-Gunn, J.; Klebanov, P.K. Enhancing the development of low-birthweight, premature infants: Changes in cognition and behaviour over the first three years. Child Dev. 1993, 64, 736–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Als, H.; Butler, S.; Kosta, S.; Mc Anulty, G. The assessment of preterm infants’ behavior (APIB): Furthering the understanding and measurement of neurodevelopmental competence in preterm and full-term infants. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2005, 11, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brazelton, T.B. Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale; William Heinemann Medical Books Ltd.: London, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Koldewijn, K.; Wolf, M.J.; Pierrat, V.; van Wassenaer-Leemhuis, A.; Wolke, D. European Standards of Care for Newborn Health: Post-Discharge Responsive Parenting Programmes. Available online: https://newborn-health-standards.org/responsive-parenting-programme/ (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- WHO World Health Organization. Constitution of the World Health Organization (Basic Documents 45th Ed. Suppl). World Health Organization 2006. Available online: https://www.who.int/governance/eb/who_constitution_en.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Haverkamp, B.; Bovenkerk, B.; Verweij, M.F. A practice-oriented review of health concepts. J. Med. Philos. Forum Bioeth. Philos. Med. 2018, 43, 381–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, M. Health, how should we define it? BMJ 2011, 343, 235–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serenius, F.; Källén, K.; Blennow, M.; Ewald, U.; Fellman, V.; Holmström, G.; Lindberg, E.; Lundqvist, P.; Maršál, K.; Norman, M.; et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome in extremely preterm infants at 2.5 years after active perinatal care in Sweden. JAMA 2013, 309, 1810–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treyvaud, K.; Lee, K.J.; Doyle, L.W.; Anderson, P.J. Very preterm birth influences parental mental health and family outcomes seven years after birth. J. Pediatr. 2014, 164, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leamy, M.; Bird, V.; Boutillier, C.L.; Williams, J.; Slade, M. Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: Systematic review and narrative synthesis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2011, 199, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S.; Cicchetti, D. Developmental cascades. Dev. Psychopathol. 2010, 22, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraldi, E.; Allodi, M.W.; Löwing, K.; Smedler, A.C.; Westrup, B.; Ådén, U. Stockholm preterm interaction-based intervention (SPIBI)-study protocol for an RCT of a 12-month parallel-group post-discharge program for extremely preterm infants and their parents. BMC Pediatr. 2020, 20, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundberg, B.; Lindgren, C.; Palme-Kilander, C.; Örtenstrand, A.; Bonamy, A.K.; Sarman, I. Hospital-assisted home-care after early discharge from a Swedish neonatal intensive care unit was safe and readmissions were rare. Acta Pediatr. 2016, 105, 895–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunst, C.; Espe-Sherwindt, M. Family-centred practices in early childhood intervention. In Handbook of Early Childhood Special Education; Reichow, B., Boyd, B.A., Barton, E.E., Odom, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, D.L.; Attkisson, C.C.; Hargreaves, W.A.; Nguyen, T.D. Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: Development of a general scale. Eval. Program Plan. 1979, 2, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Hayfield, N.; Terry, G. Thematic analysis. In Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences; Liamputtong, P., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Facebook Extremprematur föräldragrupp [Closed Facebook Group for Members]. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/groups/extremprematurer/ (accessed on 3 September 2020).

- Zakirova Engstrand, R.; Roll-Pettersson, L.; Westling Allodi, M.; Hirvikoski, T. Needs of grandparents of preschool-aged children with ASD in Sweden. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2019, 50, 1941–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Family and Individual, from “The Book about Sweden” by County Administrative Boards [Länsstyrelsen]. Available online: https://www.informationsverige.se/en (accessed on 14 September 2020).

- Seligman, M.E.P.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Positive Psychology: An introduction. In Flow and the Foundations of Positive Psychology: The Collected Works of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi; Csikszentmihalyi, M., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 279–298. [Google Scholar]

- Benzies, K.; Mychasiuk, R. Fostering family resiliency: A review of the key protective factors. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2008, 14, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, D.; Parker, K.C.; Zeanah, C.H. Mother’s representations of their infants assessed prenatally: Stability and association with infant attachment classifications. J. Child Psychiatry 1997, 38, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treyvaud, K.; Spittle, A.; Anderson, P.J.; O’Brien, K. Best practice guidelines: A multilayered approach is needed in the NICU to support parents after preterm birth of their infant. Early Hum. Dev. 2019, 139, 104838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serenius, F.; Ewald, U.; Farooqi, A.; Fellman, V.; Hafström, M.; Hellgren, K.; Maršál, K.; Ohlin, A.; Olhager, E.; Stjernqvist, K.; et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes among extremely preterm infants 6.5 years after active perinatal care in Sweden. JAMA Pediatr. 2016, 170, 954–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andel Personer Med Utländsk Bakgrund 2019 jämfört Med 2018 from SCB, Statistics of Sweden. Available online: https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/statistik-efter-amne/befolkning/befolkningens-sammansattning/befolkningsstatistik/pong/tabell-och-diagram/topplistor-kommuner/andel-personer-med-utlandsk-bakgrund/ (accessed on 19 March 2020).

- Statistics on Persons with Foreign Background, Guidelines and Recommendations from SCB, Statistics Sweden. (MIS 2002:3). Available online: https://www.scb.se/contentassets/60768c27d88c434a8036d1fdb595bf65/mis-2002-3.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Liu, C.; Urquia, M.; Cnattingius, S.; Hjern, A. Migration and preterm birth in war refugees: A Swedish cohort study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 29, 141–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, A.J.; Zimbeck, M.; Zeitlin, J.; ROAM Collaboration; Alexander, S.; Blondel, B.; Buitendijk, S.; Desmeules, M.; Di Lallo, D.; Gagnon, A.; et al. Migration to western industrialized countries and perinatal health: A systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 69, 934–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Interview Guide | Additional (IG) Interview Guide |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Main Theme | Subthemes | Dealing with Issues of |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Child-related concerns | Continued medical concerns | Diagnoses and technical supplies. |

| Child regulation | Questions of eating, sleeping, and digestion. | |

| Incomplete recovery when coming home | The timing of discharge, medical assessment of the child’s state versus the parental perception of the child’s state. | |

| 2. Parental inner state | Loneliness | From a practical and existential perspective. |

| Ambivalence | Towards different aspects of the process (i.e., the feeling of relief mixed with worry, or happiness for one’s own child’s development mixed with guilt towards other less fortunate parents). | |

| Premature parental identity | Opposing drives of keeping or letting go of the premature parent label and social media support from peers. | |

| 3. Changed family dynamics | The parental dyad | Differences in reactions ranging from complementing parental skills to more severe disagreements within the parental dyad was reported in 10 of the 14 families. |

| Thoughts relating to siblings | (Both in an enriching sense in terms of parenting experience and in a worrisome sense in terms of prioritizing parental attention). In the case of the first child, the absence of siblings was sometimes discussed. | |

| Intergenerational support | When asked about non-hospital related support during the first year at home, grandmothers and grandfathers of the child were mentioned as a main source of help. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baraldi, E.; Allodi, M.W.; Smedler, A.-C.; Westrup, B.; Löwing, K.; Ådén, U. Parents’ Experiences of the First Year at Home with an Infant Born Extremely Preterm with and without Post-Discharge Intervention: Ambivalence, Loneliness, and Relationship Impact. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9326. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249326

Baraldi E, Allodi MW, Smedler A-C, Westrup B, Löwing K, Ådén U. Parents’ Experiences of the First Year at Home with an Infant Born Extremely Preterm with and without Post-Discharge Intervention: Ambivalence, Loneliness, and Relationship Impact. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(24):9326. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249326

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaraldi, Erika, Mara Westling Allodi, Ann-Charlotte Smedler, Björn Westrup, Kristina Löwing, and Ulrika Ådén. 2020. "Parents’ Experiences of the First Year at Home with an Infant Born Extremely Preterm with and without Post-Discharge Intervention: Ambivalence, Loneliness, and Relationship Impact" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 24: 9326. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249326

APA StyleBaraldi, E., Allodi, M. W., Smedler, A.-C., Westrup, B., Löwing, K., & Ådén, U. (2020). Parents’ Experiences of the First Year at Home with an Infant Born Extremely Preterm with and without Post-Discharge Intervention: Ambivalence, Loneliness, and Relationship Impact. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24), 9326. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249326