Towards a HR Framework for Developing a Health-Promoting Performance Culture at Work: A Norwegian Health Care Management Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theory

2.1. Organisational Culture and Health-Promoting Performance Culture

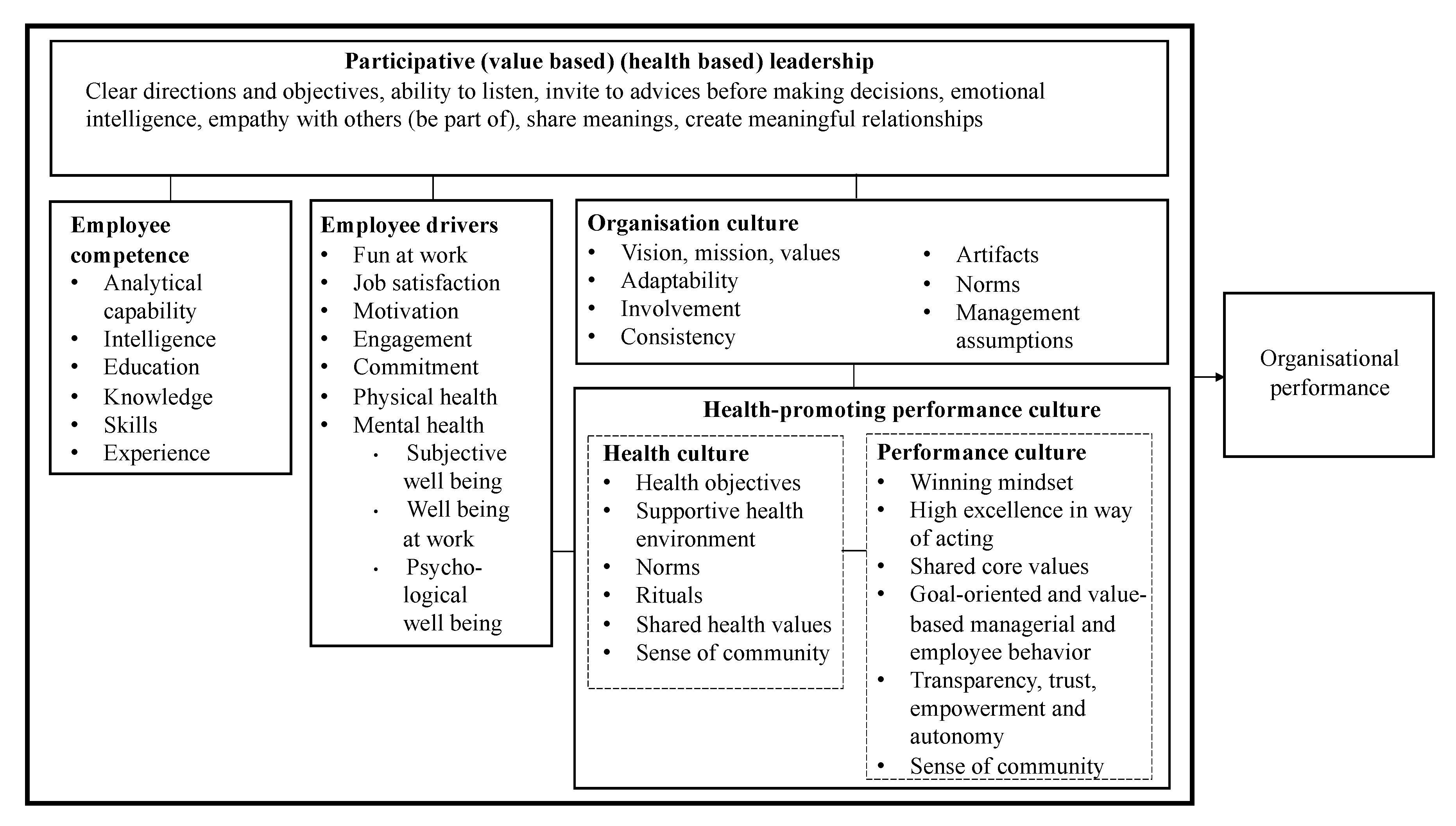

A health culture is an inspiring ecosystem with shared health objectives, norms, and health values, which are supported by participative leadership, a supportive environment such as physical facilities and common employee touch points stimulating employee physical activity and sense of community to foster employee physical and mental health.

A type of organisational culture that is characterised by participative leadership, a winning mindset, value-based managerial and employee behaviour, norms, rituals, a sense of community, and a supportive health environment that contributes to achieving ambitious health and social goals, so that employees can perform to the highest levels, without mental or physical strain.

2.2. Facilitation of Physical Activities in the Workplace

3. Materials and Method

3.1. Design, Data Collection and Analysis

3.2. The Cases

3.2.1. Findus

3.2.2. Schibsted

3.2.3. Gjensidige

3.2.4. Wilhelmsen

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Implications

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Statistics Norway. 2020. Available online: https://www.ssb.no/helsesat (accessed on 4 May 2020).

- NIPH. Folkehelserapporten. 2018. Available online: https://www.fhi.no/publ/2018/fhr-2018/ (accessed on 4 May 2020).

- Proper, K.I.; Van den Heuvel, S.G.; De Vroome, E.M.; Hildebrandt, V.H.; Van der Beek, A.J. Dose–response relation between physical activity and sick leave. Br. J. Sports Med. 2006, 40, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pronk, N.P.; Kottke, T.E. Physical activity promotion as a strategic corporate priority to improve worker health and business performance. Prev. Med. 2009, 49, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, L.M.; Quinn, T.A.; Glanz, K.; Ramirez, G.; Kahwati, L.C.; Johnson, D.B.; Katz, D.L. The effectiveness of worksite nutrition and physical activity interventions for controlling employee overweight and obesity: A systematic review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 37, 340–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuoppala, J.; Lamminpää, A.; Husman, P. Work health promotion, job well-being, 863 and sickness absences—A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2008, 50, 1216–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losina, E.; Yang, H.Y.; Deshpande, B.R.; Katz, J.N.; Collins, J.E. Physical activity and unplanned illness-related work absenteeism: Data from an employee wellness program. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MEMU. Hva Koster Sykefraværet for Bedriftene? 2018. Available online: https://memu.no/artikler/hva-koster-sykefravaeret-for-bedriftene/ (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Lillegrein, N.O. Korttidssykefravær Kostet Næringslivet 36 Milliarder i 2017. 2018. Available online: https://www.dinbedrift.no/2713-2/ (accessed on 4 May 2020).

- Statistics Norway. 2020. Available online: https://www.ssb.no/regsys (accessed on 4 May 2020).

- Bono, J.E.; Glomb, T.M.; Shen, W.; Kim, E.; Koch, A.J. Building positive resources: Effects of positive events and positive reflection on work stress and health. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 1601–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamarck, T.W.; Schwartz, J.E.; Shiffman, S.; Muldoon, M.F.; Sutton-Tyrrell, K.; Janicki, D.L. Psychosocial stress and cardiovascular risk: What is the role of daily experience? J. Personal. 2005, 73, 1749–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, E.R.; LePine, J.A.; Rich, B.L. Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetrick, L.E.; Quick, J.C.E. Prevention at work: Public health in occupational settings. In Handbook of Occupational Health Psychology; Quick, J.C., Tetrick, L.E., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Golaszewski, T.; Hoebbel, C.; Crossley, J.; Foley, G.; Dorn, J. The reliability and validity of an organizational health culture audit. Am. J. Health Stud. 2008, 23, 116–123. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, M.T.; Cerasoli, C.P.; Higgins, J.A.; Decesare, A.L. Relationships between psychological, physical, and behavioural health and work performance: A review and meta-analysis. Work Stress 2011, 25, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caverley, N.; Cunningham, J.B.; MacGregor, J.N. Sickness presenteeism, sickness absenteeism, and health following restructuring in a public service organization. J. Manag. Stud. 2007, 44, 304–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, W.A. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 692–724. [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; Smith, T.B.; Baker, M.; Harris, T.; Stephenson, D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 10, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baicker, K.; Cutler, D.; Song, Z. Workplace wellness programs can generate savings. J. Health Aff. 2010, 29, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, L.L.; Mirabito, A.M.; Baun, W.B. What’s the hard return on employee wellness programs? Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 20–21. [Google Scholar]

- Commissaris, D.A.; Huysmans, M.A.; Mathiassen, S.E.; Srinivasan, D.; Koppes, L.L.; Hendriksen, I.J. Interventions to reduce sedentary behavior and increase physical activity during productive work: A systematic review. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2016, 42, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetzel, R.Z.; Henke, R.M.; Tabrizi, M.; Pelletier, K.R.; Loeppke, R.; Ballard, D.W.; Kelly, R.K. Do workplace health promotion (wellness) programs work? J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2014, 56, 927–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoert, J.; Herd, A.M.; Hambrick, M. The role of leadership support for health promotion in employee wellness program participation, perceived job stress, and health behaviours. Am. J. Health Promot. 2018, 32, 1054–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passey, D.G.; Brown, M.C.; Hammerback, K.; Harris, J.R.; Hannon, P.A. Managers’ support for employee wellness programs: An integrative review. Am. J. Health Promot. 2018, 32, 1789–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barley, S.R. Semiotics and the study of occupational and organizational cultures. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 1983, 28, 393–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, P. Metaphors of the field: Varieties of organisational discourse. Adm. Sci. Q. 1979, 24, 660–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.M. Understanding organisational culture and the implications for corporate marketing. Eur. J. Mark. 2001, 35, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, E.J. Organizational Culture and Leadership; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Yauch, C.A.; Steudel, H.J. Complementary use of qualitative and quantitative cultural assessment methods. Organ. Res. Methods 2003, 6, 465–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denison, D.R. Corporate Culture, and Organizational Effectiveness; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Denison, D.R. Organizational culture: Can it be a key lever for driving organizational change? In The Handbook of Organizational Culture; Cooper, S., Cartwright, C., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Denison, D.R. Bringing corporate culture to the bottom line. Organ. Dyn. 2001, 13, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denison, D.R.; Mishra, A.K. Toward a theory of organizational culture and effectiveness. Organ. Sci. 1995, 6, 204–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikpour, A. The impact of organizational culture on organizational performance: The mediating role of employee’s organizational commitment. Int. J. Organ. Leadersh. 2017, 6, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, F.; Iqbal, Z.; Gulzar, M. Impact of organizational culture on employees job performance: An empirical study of software houses in Pakistan. J. Bus. Stud. Q. 2013, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, B.R.; Minsky, B.D. The Role of Climate and Socialisation in Developing Interfunctional Coordination. Learn. Organ. 2002, 9, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ind, N.; Bjerke, R. Branding Governance: A Participatory Approach to the Brand Building Process; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mellor, V. Delivering brand values through people. Strateg. Commun. Manag. 1999, 3, 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ind, N.; Bjerke, R. The concept of participatory market orientation: An organisation-wide approach to enhancing brand equity. J. Brand Manag. 2007, 15, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ind, N. Living the Brand: How to Transform Every Member of Your Organization into a Brand Champion; Kogan Page Publishers: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kaliprasad, M. The human factor II: Creating a high performance culture in an organization. Cost Eng. 2006, 48, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, B.; Lane, H. Exploring the distinctions between a high performance culture and a cult. Strategy Leadersh. 2007, 35, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Waal, D. Successful performance management? Apply the strategic performance management development cycle! Meas. Bus. Excell. 2007, 11, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.W.; Lin, Y.Y. A multilevel model of organizational health culture and the effectiveness of health promotion. Am. J. Health Promot. 2014, 29, e53–e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zohar, D.M.; Hofmann, D.A. Organizational culture and climate. In The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Psychology; Kozlowski, S.W.J., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, R.F.; Allen, J. A sense of community, a shared vision and a positive culture: Core enabling factors in successful culture based health promotion. Am. J. Health Promot. 1986, 1, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJoy, D.M. Behavior change versus culture change: Divergent approaches to managing workplace safety. Saf. Sci. 2005, 43, 105–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurt, J.; Elke, G. Health promoting leadership: The mediating role of an organizational health culture. In Ergonomics and Health Aspects of Work with Computers; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2009; pp. 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Golaszewski, T.; Allen, J.; Edington, D. The art of health promotion. Am. J. Health Promot. 2008, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoebbel, C.; Golaszewski, T.; Swanson, M.; Dorn, J. Associations between the worksite environment and perceived health culture. Am. J. Health Promot. 2012, 26, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeroy, K.R.; Bibeau, D.; Steckler, A.; Glanz, K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ. Q. 1988, 15, 351–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, J. Rethinking Strategic HR; CCH Incorporated: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Luna-Arocas, R.; Camps, J. A model of high performance work practices and turnover intentions. Pers. Rev. 2008, 37, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loehr, J. Become fully engaged. Leadersh. Excell. 2005, 22, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, S.L.; Bakker, A.B.; Gruman, J.A.; Macey, W.H.; Saks, A.M. Employee engagement, human resource management practices and competitive advantage. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2015, 2, 7–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ployhart, R.E.; Moliterno, T.P. Emergence of the human capital resource: A multilevel model. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2011, 36, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, F.L.; Hunter, J.E. The validity and utility of selection methods in personnel psychology: Practical and theoretical implications of 85 years of research findings. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 124, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B.; Wright, P.M. On becoming a strategic partner: The role of human resources in gaining competitive advantage. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1998, 37, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaggs, B.C.; Youndt, M. Strategic positioning, human capital, and performance in service organizations: A customer interaction approach. Strateg. Manag. J. 2004, 25, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, K.E.; Marsick, V.J. Make learning count! Diagnosing the learning culture in organizations. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2003, 5, 132–151. [Google Scholar]

- Downward, P.; Rasciute, S. Does sport make you happy? An analysis of the well-being derived from sports participation. Int. Rev. Appl. Econ. 2011, 25, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, S.; Bray, J.; Brown, L. Enabling healthy food choices in the workplace: The canteen operators’ perspective. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2017, 10, 318–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, K.M.; Vella-Brodrick, D.A. The ‘what’, ‘why’ and ‘how’ of employee well-being: A new model. Soc. Indic. Res. 2009, 90, 441–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Ashford, S.J. The dynamics of proactivity at work. Res. Organ. Behav. 2008, 28, 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzberg, F. One more time: How do you motivate employees? Harv. Bus. Rev. 2003, 81, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ryff, C.D.; Keyes, C.L.M. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, C.P.; Baltes, B.B.; Young, S.A.; Huff, J.W.; Altmann, R.A.; Lacost, H.A.; Roberts, J.E. Relationships between psychological climate perceptions and work outcomes: A meta-analytic review. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2003, 24, 389–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tews, M.J.; Michel, J.W.; Stafford, K. Does Fun Pay? The Impact of Workplace Fun on Employee Turnover and Performance. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2013, 54, 370–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tews, M.J.; Michel, J.W.; Allen, D.G. Fun and friends: The impact of workplace fun and constituent attachment on turnover in a hospitality context. Hum. Relat. 2014, 67, 923–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peluchette, J.; Karl, K.A. Attitudes toward incorporating fun into the health care workplace. Health Care Manag. 2005, 24, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedarkar, M.; Pandita, D. A study on the drivers of employee engagement impacting employee performance. Procedia-Social and Behav. Sci. 2014, 133, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mello, C.; Wildermuth, A.; Pauken, S. A perfect march: Decoding employees engagement Part 1: Engaging Culture and Leaders. Ind. Commer. Train. 2008, 40, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Towards a model of work engagement. Career Dev. Int. 2008, 13, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J. Transformational leadership and organizational culture. Public Adm. Q. 1993, 17, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, N.C.; Sallis, J.F.; Conway, T.L.; Saelens, B.E.; Frank, L.D. Worksite physical activity policies and environments in relation to employee physical activity. Am. J. Health Promot. 2011, 25, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brynjolfsson, E.; Hitt, L.M.; Yang, S. Intangible assets: Computers and organizational capital. Brook. Pap. Econ. Act. 2002, 2002, 137–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerke, R.; Elvekrok, I. Sponsorship-based health care programs and their impact on employees’ motivation for physical activity. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2020, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, L.; Leidner, D.; Gonzalez, E. The role of Fitbits in corporate wellness programs: Does step count matter? In Proceedings of the 50th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Atreja, A.; Mehta, N.B.; Jain, A.K.; Harris, C.M.; Ishwaran, H.; Avital, M.; Fishleder, A.J. Satisfaction with web-based training in an integrated healthcare delivery network: Do age, education, computer skills and attitudes matter? BMC Med Educ. 2008, 8, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benbya, H.; Passiante, G.; Belbaly, N.A. Corporate portal: A tool for knowledge management synchronization. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2004, 24, 201–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, T.C.; Shank, M.D. Athletes as product endorsers: The effect of gender and product relatedness. Sport Mark. Q. 2004, 13, 82–93. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L.; Gutmann, M.L.; Hanson, W.E. Handbook on Mixed Methods in the Behavioral and Social Sciences: Advanced Mixed Methods Research Designs; Tashakkori, A., Teddlie, C., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 209–240. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, P.; Jack, S. Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. Qual. Rep. 2008, 13, 544–559. [Google Scholar]

- Golafshani, N. Understanding reliability and validity in qualitative research. Qual. Rep. 2003, 8, 597–606. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow, S.L. Quality and trustworthiness in qualitative research in counseling psychology. J. Couns. Psychol. 2005, 52, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenton, A.K. Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Educ. Inf. 2004, 22, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Farrelly, P. Choosing the right method for a qualitative study. Br. J. Sch. Nurs. 2013, 8, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tveito, T.H.; Halvorsen, A.; Lauvålien, J.V.; Eriksen, H.R. Room for everyone in working life? 10% of the employees—82% of the sickness leave. Nor. Epidemiol. 2002, 12, 63–68. [Google Scholar]

- Spiggle, S. Analysis and interpretation of qualitative data in consumer research. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geertz, C. Local Knowledge: Further Essays in Interpretive Anthropology; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Reconstructing grounded theory. In The SAGE Handbook of Social Research Methods; SAGE Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 461–478. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Weate, P. Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research. In Routledge Handbook of Qualitative Research Methods in Sport and Exercise; Smith, B., Sparkes, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 191–205. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Findus. Våre Medarbeidere er vår Fremste Styrke. 2020. Available online: https://www.findus.no/brekraft/hvordan-gjor-vi-en-forskjell/vare-medarbeidere (accessed on 12 May 2020).

- Gjensidige. Om oss. 2020. Available online: https://www.gjensidige.no/konsern/ (accessed on 12 May 2020).

- Amlani, N.M.; Munir, F. Does physical activity have an impact on sickness absence? A review. Sports Med. 2014, 44, 887–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornwell, T.B.; Howard-Grenville, J.; Hampel, C.E. The company you keep: How an organization’s horizontal partnerships affect employee organizational identification. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2018, 43, 772–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Company/ Features | Findus | Schibsted | Gjensidige | Wilhemsen |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of employees and participants of employee physical activity | 45 people work in the main office where the facilities are located. Around 10–15 employees participate in common activities on a regular basis. | In the main office, where the gym is, there are 1200 employees and about 450 in a nearby location. There is room for 35 participants per training hour and may be 150–200 use the facilities during a week. Around 150 people are logged in during home based online training sessions. | About 150 employees use the facilities daily (out of 820 in the main Oslo-office and 350 in a nearby location). | Of 300 employees in the main office, about 30–40 employees use the facilities and activity offers on a daily basis. |

| Physical facilities | Sharing facilities with other companies. Fitness and spinning rooms. Locker rooms and showers. | A large fitness centre, which includes two activity rooms | Large gymnasium, spinning room, sauna, locker rooms, showers, bicycle parking | Gymnasium and strength room. Wardrobes with facilities. |

| Health promoting programs and organising | The HR-based ‘Our Well Way’. | Various common activities like yoga organised by volunteers. | Various sessions organised by volunteers or professional instructors. | Offers several sport team activities in the gym organised by the sport team (volunteers) or professional instructors. |

| Canteen and diet | Green weekdays with meat-free meals, free fruits and canteen food with a healthy and varied diet. | Promotion of different themes on a weekly or daily basis such as green days. All employees receive free water, coffee and fruits. | Own canteen personnel put strict requirements on the canteen food. Healthy food and green meals. | Company chefs and canteen staff emphasizing serving healthy, green and nutritious food. Vegetarian days. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bjerke, R. Towards a HR Framework for Developing a Health-Promoting Performance Culture at Work: A Norwegian Health Care Management Case Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9164. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249164

Bjerke R. Towards a HR Framework for Developing a Health-Promoting Performance Culture at Work: A Norwegian Health Care Management Case Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(24):9164. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249164

Chicago/Turabian StyleBjerke, Rune. 2020. "Towards a HR Framework for Developing a Health-Promoting Performance Culture at Work: A Norwegian Health Care Management Case Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 24: 9164. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249164

APA StyleBjerke, R. (2020). Towards a HR Framework for Developing a Health-Promoting Performance Culture at Work: A Norwegian Health Care Management Case Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24), 9164. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249164