Woman, Mother, Wet Nurse: Engine of Child Health Promotion in the Spanish Monarchy (1850–1910)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Review Process

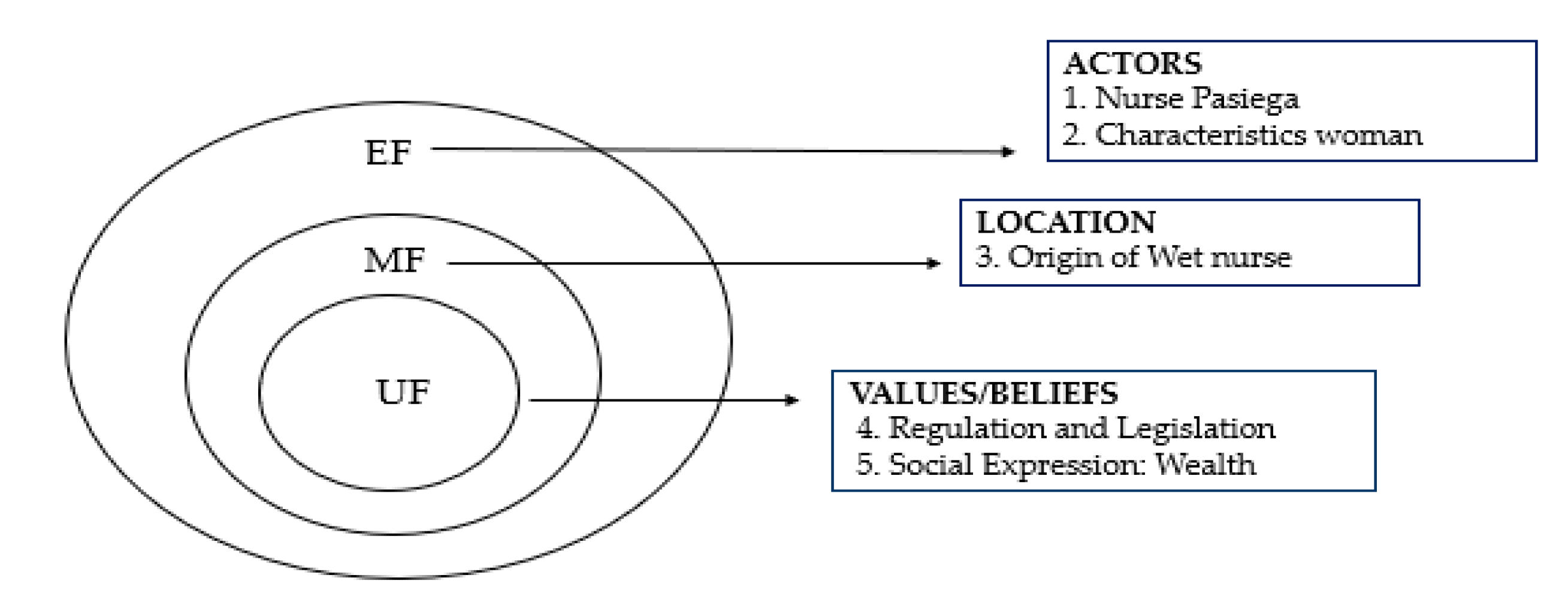

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

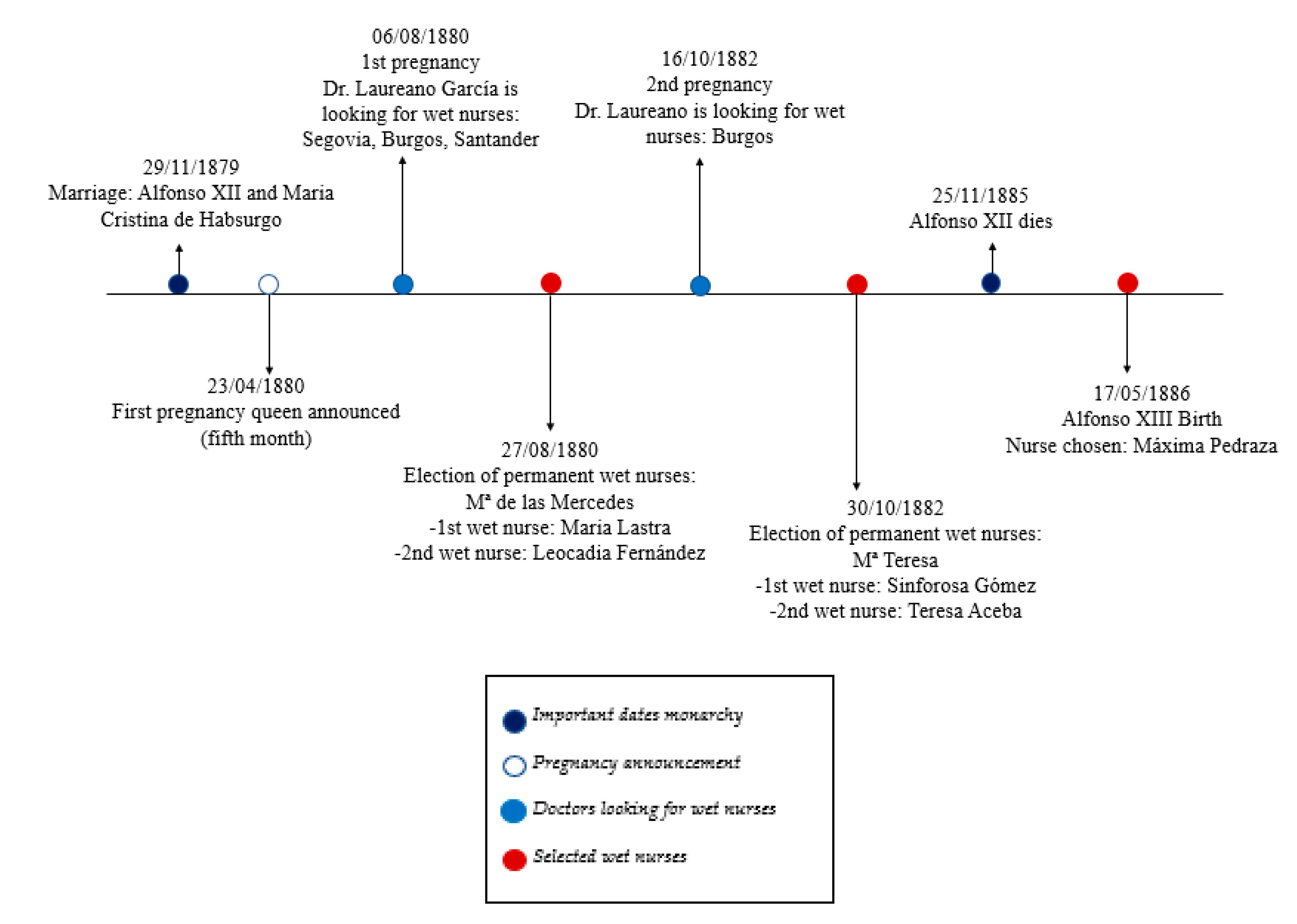

3.1. The Rise of the Northern Wet Nurses

3.2. Physical and Moral Characteristics of Northern Wet Nurses

3.3. Origin of the Monarchical Wet Nurse

3.4. Legislation and Regulation of the Job of the Wet Nurse

3.5. Wet Nurse’s Costume: A Social Expression of Wealth

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Dialectical structural model of care | DSMC |

| Functional unit | UF |

| Functional framework | MF |

| Functional element | EF |

References

- Espinosa, M.C. La Lactancia Cómo Profesión: Una Mirada al Oficio de Nodriza; Archivo Histórico Diocesano de Jaén: Jaén, Spain, 2012; p. 30. Available online: https://www.revistacodice.es/publi_virtuales/iv_congreso_mujeres/comunicaciones/MANUELCABRERA.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Martínez Sabater, A.; Siles González, J.; Solano Ruiz, C.; Saus Ortega, C. Visión social de las nodrizas en el periódico ‘La Vanguardia’ (1881–1908). Dilemata. Rev. Int. Éticas Appl. 2017, 25, 69–84. [Google Scholar]

- Galiana, A.A. Real Academia Española. 2019. Available online: https://dle.rae.es/nodriza (accessed on 21 May 2020).

- Amo del Amo, M.C. La Familia y el Trabajo Femenino en España Durante la Segunda Mitad del Siglo XIX; Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Servicio de Publicaciones: Madrid, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yalom, M.; Puigrós, A. Historia del Pecho; Tusquets Editores: Barcelona, Spain, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Sabater, A. Las Nodrizas y su Papel en el Desarrollo de la Sociedad Española: Una Visión Transdisciplinar. Las Nodrizas en la Prensa Española del Siglo XIX y Principios del Siglo XX. 2014. Available online: https://rua.ua.es/dspace/bitstream/10045/39874/1/tesis_martinez_sabater.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2020).

- Antonio, M.S. Las nodrizas y su importancia en los cuidados. Cult. Cuid. Rev. Enferm. Hum. 2014, 40, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Sabater, A.; Juárez-Colom, J.; Solano-Ruiz, M.; Siles González, J. Las nodrizas en el periódico ABC (1903–1920). Cult. Cuid. Rev. Enferm. Hum. 2017, 48, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, B.E. La elección de las nodrizas en las clases altas, del siglo XVII al siglo XIX. Matronas Prof. 2013, 3, 68–73. [Google Scholar]

- Siles-González, J. La Industria de las Nodrizas en Alicante, 1868–1936; Asociación de Historia Social: Córdoba, Spain, 1996; pp. 367–372. [Google Scholar]

- Reglamento General de la Beneficencia Pública, 1st ed.; Imprenta Manuel Muñoz: Valencia, Spain, 1821; Volume 1, Available online: https://bvpb.mcu.es/es/consulta/registro.do?id=398366 (accessed on 26 April 2020).

- Teixidor, C.G.I. Los límites de la acción social en la España del siglo XIX asistencia y salud pública en los orígenes del Estado Liberal. Hispania 2000, 60, 597–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reglamento del 9 Marzo. Generales que Deben Tener las Nodrizas Externas; Secc. Beneficencia. S1; Archivo de la Diputación Provincial de Alicante: Alicante, Spain, 1862; Volume 434. [Google Scholar]

- Ocaña, E.R. Aspectos Sociales de la Pediatría Española Anteriores a la Guerra Civil: (1936–1939); Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, CSIC: Madrid, Spain, 1985; pp. 443–459. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Alcubilla, M. Diccionario de la Administración Española. In Compilación de la Novísima Legislación Española en Todos los Ramos de la Administración Pública; 1886; Volume 12, Available online: https://citarea.cita-aragon.es/citarea/handle/10532/1349 (accessed on 12 June 2020).

- Dios-Aguado, M.D.; Gómez-Cantarino, S.; Rodríguez-López, C.R.; Queirós, P.J.P.; Romera-Álvarez, L.; Espina-Jerez, B. Breastfeeding and feminism: Social and cultural journey in Spain. Escola Anna Nery 2020, 25, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deslandes, M. Compendio de Higiene Pública y Privada ó Tratado Elemental de los Elementos Relativo a la Conservación de la Salud y la Perfección Física y Moral de los Hombres. In Imprenta de la Oliva; Oficina Oliva: Gerona, Spain, 1829; Available online: https://books.google.es/books/ucm?vid=UCM5308594844&printsec=frontcover&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 9 February 2020).

- Fabre, A.F.H. Tratado Completo de las Enfermedades de las Mujeres; La Viuda de Jordan e Hijos: Madrid, Spain, 1845; Volume 44, pp. 155–156. Available online: https://books.google.es/books?id=u1m7URs8e4wC&printsec=frontcover&hl=es&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 17 February 2020).

- López Arroyo, L. Reconocimiento de Nodrizas. In Imprenta de M.P. Montoya; M.P Montoya: Madrid, Spain, 1889; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, J. Importancia de los modelos para el cuidado. In Modelos de Enfermería; Kreshaw, B., Salvage, J., Eds.; Doyma: Barcelona, Spain, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Siles González, J. La eterna guerra de la identidad enfermera: Un enfoque dialéctico y deconstruccionista. Index Enferm. 2005, 14, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siles González, J. La construcción social de la Historia de la Enfermería. Index Enferm. 2004, 13, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siles González, J.; Solano Ruiz, C. El Modelo Estructural Dialéctico de los Cuidados. Una guía facilitadora de la organización, análisis y explicación de los datos en investigación cualitativa. CIAIQ2016 2016, 2, 211–220. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquhoun, H.L.; Levac, D.; O’Brien, K.K.; Straus, S.; Tricco, A.C.; Perrier, L.; Kastner, M.; Moher, D. Scoping reviews: Time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 1291–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barona, J.L.; Mestre, J.B. La Salud y el Estado: El Movimiento Sanitario Internacional y la Administración Española, 1815–1945; Universitat de València: Valencia, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Anguita Osuna, J.E.; Soto, S. Aportaciones Históricas y Jurídicas Sobre el Reinado de Fernando VII; Dykinson: Madrid, Spain, 2019; pp. 1–238. [Google Scholar]

- Gustavo, C. El Traje en Cantabria; El diario montañés: Santander, Spain, 1999; Volume 1, pp. 121–132. [Google Scholar]

- Gacho Santamaria, M.A. Médicos y nodrizas en la Corte española (1625–1830). R. Sitios Rev. Patrim. Nac. 1995, 31, 124. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, J.M.F. Amas de cría. Campesinas en la urbe. Rev. Folk. 1999, 221, 147–159. [Google Scholar]

- Cortés Echanove, L. Nacimiento y Crianza de Personas Reales en la Corte de España, 1566–1886; CSIC: Madrid, Spain, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Buldain, B. Historia Contemporánea de España, 1808–1923; Akal: Madrid, Spain, 2011; Volume 1, pp. 129–272. [Google Scholar]

- Espasa, H.d.J. Enciclopedia Universal Ilustrada Europeo-Americana; Espasa-Calpe: Barcelona, Spain, 1920; Volume 42, p. 1435. [Google Scholar]

- Libreta de Nodrizas. 1889. Available online: https://www.boe.es/datos/pdfs/BOE//1889/033/A00302-00303.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2020).

- Aguilar Cordero, M.; Álvarez Gómez, J.L. Lactancia Materna; Elsevier: Madrid, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Iberti, J. Método Artificial de Criar á los Niños Recien Nacidos, y de Darles una Buena Educacion Fisica; Seguida de un Tratado Sobre las Enfermedades de la Infancia; en la Imprenta Real: Madrid, Spain, 1795; pp. 206–216. Available online: https://books.google.es/books/ucm?vid=UCM532353237X&printsec=frontcover&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Siles, J.; Gabaldón, E.; Tolero, D.; Gallardo, Y.; García Hernández, E.; Galao, R. El eslabón biológico en la historia de los cuidados de salud, el caso de las nodrizas: Una visión antropológica de la enfermería. Index Enferm. 1998, 7, 16–23. Available online: http://www.index-f.com/index-enfermeria/20-21revista/r20-21_articulo_16-23.php (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Junceda Avello, E. Ginecología y vida íntima de las reinas de España. Madr. Ed. Temas Hoy 1992, 2, 132–154. [Google Scholar]

- Toquero Sandoval, C. Reglas para escoger amas, y leche. Cadiz, España. 1617. Available online: http://dioscorides.ucm.es/proyecto_digitalizacion/index.php?doc=b17857338&y=2011&p=2 (accessed on 18 May 2020).

- Zabía Lasala, M.P. Diccionario de Juan Alonso y de los Ruyzes de Fontecha; Arco Libros: Madrid, Spain, 1999; pp. 9–23. [Google Scholar]

- Amezcua, M. La estética de las Amas de Cría. Exposición fotográfica en la Fundación Joaquín Díaz. Index Enferm. 2000, 30, 8–61. Available online: http://www.index-f.com/index-enfermeria/30revista/30_articulo_58-61.php (accessed on 13 June 2020).

- Sarasúa, C. Criados, nodrizas y amos: El servicio doméstico en la formación del mercado de trabajo madrileño, 1758–1868. Madr. Siglo XXI Esp. Ed. 1994, 1, 127–132. [Google Scholar]

- Fildes, V. Breasts, Bottles and Babies—A History of Infant Feeding; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, T.G. Estudio del papel del ama de cría pasiega en la crianza española del s. XIX y principios del s. XX. Nuberos Cient. 2012, 1, 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, I. Orígenes del Liberalismo. Universidad, Política, Economía; Universidad de Salamanca: Salamanca, Spain, 2003; Volume 124. [Google Scholar]

- Soler, E. Familias, Jerarquización y Movilidad social. In Parentesco de Leche y Movilidad Social. La Nodriza Pasiega; Universidad de Murcia: Murcia, Spain, 2010; pp. 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Casassas, J. La construcción del Presente: El Mundo Desde 1848 Hasta Nuestros Días; Grupo Planeta: Barcelona, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Orzaes, M.D.C.C. Nodrizas y lactancia mercenaria en España durante el primer tercio del siglo XX. Arenal Rev. Hist. Mujeres 2007, 14, 335–359. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar-Agulló, M. Asistencia Materno-Infantil y Cuestiones de Género en el Programa “Al Servicio de España y del Niño Español” (1938–1963); Universidad de Alicante: Alicante, Espana, 2009; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10045/14044 (accessed on 11 May 2020).

- Scott, J. La mujer trabajadora en el siglo XIX. Hist. Mujeres 1993, 4, 425–461. [Google Scholar]

- Martín, A.M.R. El destino de los niños de la inclusa de Pontevedra, 1872–1903. Cuad. Estud. Gallegos 2008, 55, 353–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vilar, P.; Folch, M.D. Iniciación al Vocabulario del Análisis histórico; Crítica: Barcelona, Spain, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Monerris, E.G.; Seco, M.M.; Benedicto, J.I.M. Culturas Políticas Monárquicas en la España liberal: Discursos, Representaciones y Prácticas (1808–1902); Universitat de València: Valencia, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Ferrer, G. Historia de las Mujeres en España: Siglos XIX y XX; Madrid, Cuadernos de Historia, 114; Arco: Madrid, Spain, 2011; pp. 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Canalejo, C.G. Liderazgo y Poder Político de las Enfermeras (1840–1948). Un Análisis de Género, 2018; Col. legi Oficial d’Infermeria de les Illes Balears: Illes Balears, Spain, 2018; pp. 69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras, E.M. Nodrizas rurales en el siglo XIX. Historia 16 1993, 209, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- García, R.R. Nodrizas y amas de cría. Más allá de la lactancia mercenaria. Dilemata 2017, 25, 37–54. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson Bonie, S.; Zinsser, J.Z. Historia de las Mujeres: Una Historia Propia; Critica: Barcelona, Spain, 1991; pp. 617–634. [Google Scholar]

- Arnaud-Duc, N. Wet Nursing. A History from Antiquity to the Present. JSTOR 1989, 1, 275–284. [Google Scholar]

- Fusi, J.P.; Palafox, J. España, (1808–1996): El Desafío de la Modernidad; Espasa Calpe: Madrid, Spain, 1997; Available online: https://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/CHCO/article/view/CHCO9898110299A (accessed on 12 June 2020).

- Gómez-Cantarino, S.; Romera-Álvarez, L.; Dios-Aguado, M.; Siles González, J.; Espina Jerez, B. La nodriza pasiega: Transición de la actividad biológica a la laboral (1830–1930). Cult. Cuid. Rev. Enferm. Hum. 2020, 24, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartel, K.L.; Sneeringer, L.; Cohen, S.M. From royal wet nurses to Facebook: The evolution of breastmilk sharing. Breastfeed. Rev. Prof. Publ. Nurs. Mothers Assoc. Aust. 2016, 24, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Currier, R.W.; Widness, J.A. A Brief History of Milk Hygiene and Its Impact on Infant Mortality from 1875 to 1925 and Implications for Today: A Review. J. Food Prot. 2018, 81, 1713–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, L. A short history of infant feeding and growth. Early Hum. Dev. 2012, 88 (Suppl. 1), S57–S59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Legislation | Period | Observations |

|---|---|---|

| Royal Jurisdiction of Castilla | 1252–1255 | Abandonment of children was punished. A person who let a child die for not feeding him was sentenced to death. |

| “Partidas” “Novísima Recopilación” | 1805 | They reported on how to raise children. Prevents the way to proceed in cases of orphanhood. |

| General Benefit Regulations | 27 December 1821 Art. 58–61 | Opening of a maternity home for breastfeeding. Two work periods for the wet nurses are established: two years of lactation and subsequent raising. |

| Law of 23 January 1822 | Title III. Arts.41 y 50–70 | Regulation of the living conditions of orphaned children in Charity establishments. |

| Law of 20 June 1848 | 1848 | Protection of foundlings, orphans and the homeless |

| Regulations of 9 March 1862 | 1862 | General conditions that must have the external wet nurses in Alicante. |

| Law of 12 August 1904 | 1904 | It extended its protection to all children under the age of ten, and the Higher Council for Children with Provincial and Local Boards was created as a regulatory body. |

| Regulation 24 January 1908 | 1908 | |

| Regulation 24 January 1908 | 1908 |

| Database | Search Strategy | Limits | Points Extracted | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pubmed Cochrane CINHAL Scopus Google Scholar Books | breastfeeding AND human milk human lactation AND breastfeeding breastfeeding OR human milk breastfeeding AND human lactation infant mortality AND child survival Intercultural care AND society historical research AND society breastfeeding OR health promotion wet nursing and breastfeeding nurse AND wet nursing infant care OR child survival | Title Article English/Spanish | Origin Start of the selection process Privileges of the royal wet nurses | [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36] |

| Wet nurse selection process Wet nurse’s salary | [37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46] | |||

| Origin of the monarchical wet nurse | [47,48] | |||

| Legislation | [49,50,51,52,53] | |||

| Wet nurse’s costume (wealth) | [54] |

| Author(s) | Type of Document/Study Year | Purpose | Characteristics | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Siles-Gonzalez et al. [24] | Book 2016 | Educational Anthropology of Care | Ethnography and ethnology Context: interpretative paradigm | Culture Customs Society |

| Barona, J.L. et al. [28] | Book 2008 | Spanish society’s health | Start of the selection process | Nutrition Infant feeding Breastfeeding |

| Gustavo, C. [30] | Book 1999 | The costume in Cantabria (Santander) | Pasiega wet nurse’s clothes | White color: wealth Different dress: urban/rural area Gifts Jewelry: good work Added: white clothing accessories |

| Gacho Santamaría, M.A. [31] | Journal (1995) | Doctors and wet nurses of the Spanish Court (1625–1830) | Names of physician-surgeons and wet nursing | Start of the selection process |

| Gil, J.M.F. [32] | Journal (1995) | Wet nurses Peasant women in the city | The upper social classes hired wet nurses to breastfeed the infant | Privileges of the royal wet nurses |

| Cortés Echanove. [33] | Book (1958) | Birth and upbringing of real people in the court of Spain | Contact of the monarchy with the town councils and districts, which oversaw notifying the future wet nurses | Women with more than one child; Important figure of Spanish royalty |

| Buldain, B. [34] | Book (1958) | Contemporary History of Spain, 1808–1923 | Good family health (woman, man, children) | Social perspective era: predominant functional unit |

| Espasa, H.d.J. [35] | Book (1958) | Universal Illustrated European-American Encyclopedia | Amount of hair Skin infections Digestive disorders Appropriate age of wet nurses | Anatomical and physical features a wet nurse |

| A.C.d. [36] | Notebook (1889) | Wet nurse’s notebook | Notebook, where the contracts and dismissals of the different families in which they worked were sealed | Possession of the notebook was mandatory for performing wet nurse’s work |

| Aguilar Cordero, M. [37] | Book (2005) | Breastfeeding | Ruggedness, loose clothes | Assessment test: vigorous, no breathing problems |

| Iberti, J. [38] | Manual (1789) | Artificial method of raising newborn children and giving them a good physical education | Associated features witchcraft | First moments attention child; Breeding mothers Exercise of the wet nurse |

| Siles, J. et al. [39] | Journal (1998) | The biological link in the history of health care, the case of wet nurses: An anthropological view of nursing | Arrival: medical contingency for oral transmission: priest, neighbors; Official mother’s document Official Certification | Number of the wet-nurse’s children with whom she lived, when her last child was born, her work, and her husband’s one, vaccination card, proof of good health, milk analysis, and good morals |

| Junceda Avello, E. [40] | Book (1995) | Gynecology and intimate life of the queens of Spain | Checking the quality of the milk Quota for finding a wet nurse | Rich in sugars, fats- Milk quality assessment equipment |

| Toquero Sandoval, C. [41] | Manual (1617) | Rules for choosing wet nurses and milk | Wet nurses with at least two children The children must breastfeed for at least two months | Exclusion for defects |

| Zabía Lasala, M.P. [42] | Dictionary (1999) | Dictionary of Juan Alonso and the Ruyzes de Fontecha | Milk quality testing equipment Reasons to hire a wet nurse | Scales of the time; Delegating breastfeeding to wet nurses; It was believed that breastfeeding shortened the life of the biological mother and worsened her health |

| Amezcua, M. [43] | Journal (2000) | The esthetics of the wet nurses | Wet nurse selection process Wet nurse’s salary | Difficulties of the first-time wet nurse: poorer quality milk |

| Sarasúa, C. [44] | Journal (1994) | Domestic service in the formation of the Madrid job market, 1758–1868 | Economic retribution and lifetime pay | Christian morality, values and correct customs |

| Fildes, V. [45] | Book (1986) | Breasts, bottles, and babies—a history of infant feeding | Wet nurse selection process Wet nurse’s salary | Improvement of the economic situation of the family |

| Pérez, T.G. [46] | Journal (2012) | Study of the role of the pasiega wet nurse in Spanish in the 19th and early 20th centuries | Symbology of clothing Sociocultural changes | Black and white dress, wet nurse; Improves the health of real infants Increased survival of wet nurse’s children |

| Castells, I. [47] | Book (2003) | Origins of liberalism; University, politics, economy | Origin of the monarchical wet nurse | Political reforms; Health Promotion |

| Soler, E. [48] | Book (2010) | Milk brothers and social mobility; The pasiega wet nurse; Families | Refusal to breastfeed by biological mother Relationship: rural/urban woman | Lack of knowledge about breastfeeding Gifts to wet nurse for milk quality: Objectivity of good breastfeeding: teething |

| Orzes, M.d.C.C. [50] | Journal (2007) | Nurses and mercenary breastfeeding in Spain during the first third of the 20th century | Health problems of the biological mother | Medical disorders (mastitis) |

| Salazar-Agulló, M. [51] | Book (2009) | Mother and childcare and gender issues in the program “At the Service of Spain and the Spanish Child” (1938–1963) | Individual wet nurse’s notebook reviewed by inspector | Change of address |

| Scott, J. [52] | Journal (1993) | The working woman in the 19th century; Women’s History 1993 | Wet nurses’ agency: good health good milk quality, | Essential requirements for hiring |

| Martín, A.M.R. [53] | Journal (2008) | The destiny of the children of the orphanage of Pontevedra, 1872–1903 | Nurse hiring management: multidisciplinary group | Mayor, pastor, Doctor |

| Date of Birth | Name of the Children | Physician | Wet Nurse | Husband | Place of Origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 July 1850 | Male: dies at birth due to childbirth problems | Pedro Castelló Marqués José Figuer y Cubero Doctor Pedro Gilly | Francisca Guadalupe María Pelayo Agustina de Larrañaga y Olave | Miguel González de Villegas Pedro Herrero Juan Bautista de Zabaleta | Valle de Toranzo (Santander) |

| 20 December 1851 | Mª Isabel Francisca de Asís | Jaime Drumen Dionisio Solís Francisco Alonso Rubio Francisco Alarcos | María Sabatés de Plavevall (retén) Nobody was chosen Cecilia Pastor (wet nurse chosen) Vicenta Valenciaga (2nd wet nurse) | Unknown — Facundo Montes Teodoro Celada | Vich (Barcelona) Santander, Navarra y Zaragoza Turégano (Segovia) Vasongadas |

| 5 January 1854 | Infanta Cristina (she died on 7 January 1854) | Alonso Rubio | Celestina de Diego (urgent choice for breastfeeding problem) | Dionisio Gómez | Valle del Pas |

| 11 November 1857 | Alfonso XII | Francisco Alonso Rubio Francisco Antoño Alarcós | María Gómez Josefa Ruíz Oria (2nd wet nurse) | Juan Mantecón Antonio Ruiz Navedas | Valle del Pas Valle del Pas |

| 26 December 1859 | Mª Concepción Francisca of Asís (she died before 2 years old) | Francisco Alonso Rubio Francisco Antoño Alarcós | Manuela Oria Ruiz Petra Arroyo (2nd wet nurse) | Agustín Gómez Ambrosio Vivar | Santander Burgos |

| 4 June 1861 | Mª Pilar Berengüela | Don Bruno Agüera | Juliana Revilla Araus (wet nurse chosen) Úrsula Leonor (2nd wet nurse) Manuela Cobo (wet nurse chosen) | Víctor Revilla González Unknown Unknown | Villamayor de los Montes (Burgos) Cabañas de Juarros (Burgos) San Roque de Rio Miera (Santander) |

| 23 June 1862 | Infanta Doña María de la Paz | Don Bruno Agüera | Cecilia García (2nd wet nurse) Andrea Aragón (wet nurse chosen) | Unknown Unknown | Cabañas de Juarros (Burgos) Carazo (Burgos) |

| 12 February 1864 | Doña Eulalia de Borbón | Don Manuel Izquierda | Lorenza García (2nd wet nurse) | Tomás Alonso | Carcero de Bureda (Burgos) |

| 14 February 1866 | Francisco de Asís Leopoldo (died within hours of birth) | - | - | - | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Siles-González, J.; Romera-Álvarez, L.; Dios-Aguado, M.; Ugarte-Gurrutxaga, M.I.; Gómez-Cantarino, S. Woman, Mother, Wet Nurse: Engine of Child Health Promotion in the Spanish Monarchy (1850–1910). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9005. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17239005

Siles-González J, Romera-Álvarez L, Dios-Aguado M, Ugarte-Gurrutxaga MI, Gómez-Cantarino S. Woman, Mother, Wet Nurse: Engine of Child Health Promotion in the Spanish Monarchy (1850–1910). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(23):9005. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17239005

Chicago/Turabian StyleSiles-González, José, Laura Romera-Álvarez, Mercedes Dios-Aguado, Mª. Idioia Ugarte-Gurrutxaga, and Sagrario Gómez-Cantarino. 2020. "Woman, Mother, Wet Nurse: Engine of Child Health Promotion in the Spanish Monarchy (1850–1910)" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 23: 9005. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17239005

APA StyleSiles-González, J., Romera-Álvarez, L., Dios-Aguado, M., Ugarte-Gurrutxaga, M. I., & Gómez-Cantarino, S. (2020). Woman, Mother, Wet Nurse: Engine of Child Health Promotion in the Spanish Monarchy (1850–1910). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(23), 9005. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17239005