Resilience and Anti-Stress during COVID-19 Isolation in Spain: An Analysis through Audiovisual Spots

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Stress during Isolation by COVID-19

1.2. Resilience during COVID-19 Isolation

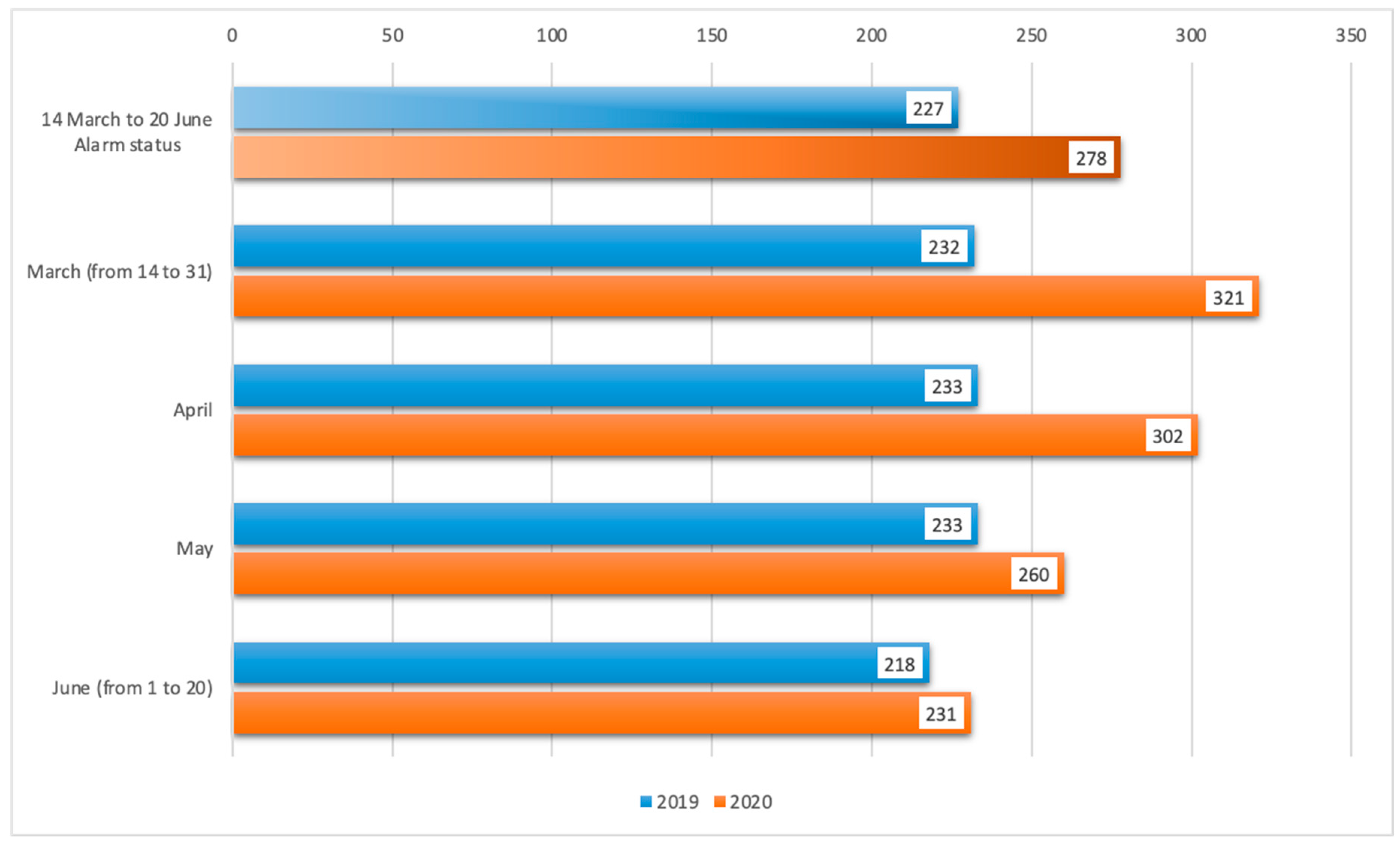

1.3. Media Consumption and Advertising during Confinement by COVID-19 in Spain

- -

- RQ1. Have the brands changed their function for supporting the dynamics of the consumer society to a social function of support in containing COVID-19 and managing the state of mental and psychological health of their audiences during confinement?

- -

- RQ2. Have companies and their brands incorporated, through the audiovisual narrative of their advertising, positive messages in favour of individual and collective resilience in Spain?

- -

- RQ3. Have companies and their brands incorporated messages that could serve as coping strategies against the psychosocial stress produced by the pandemic?

2. Materials and Methods

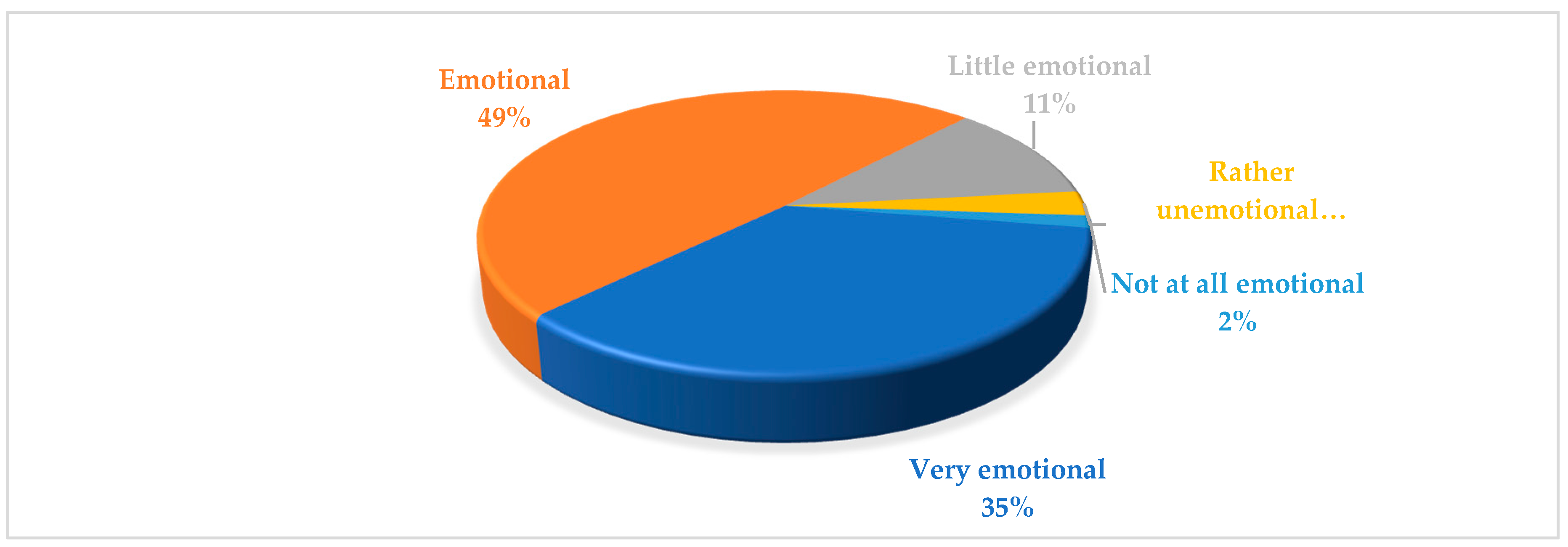

2.1. Measures and Instruments

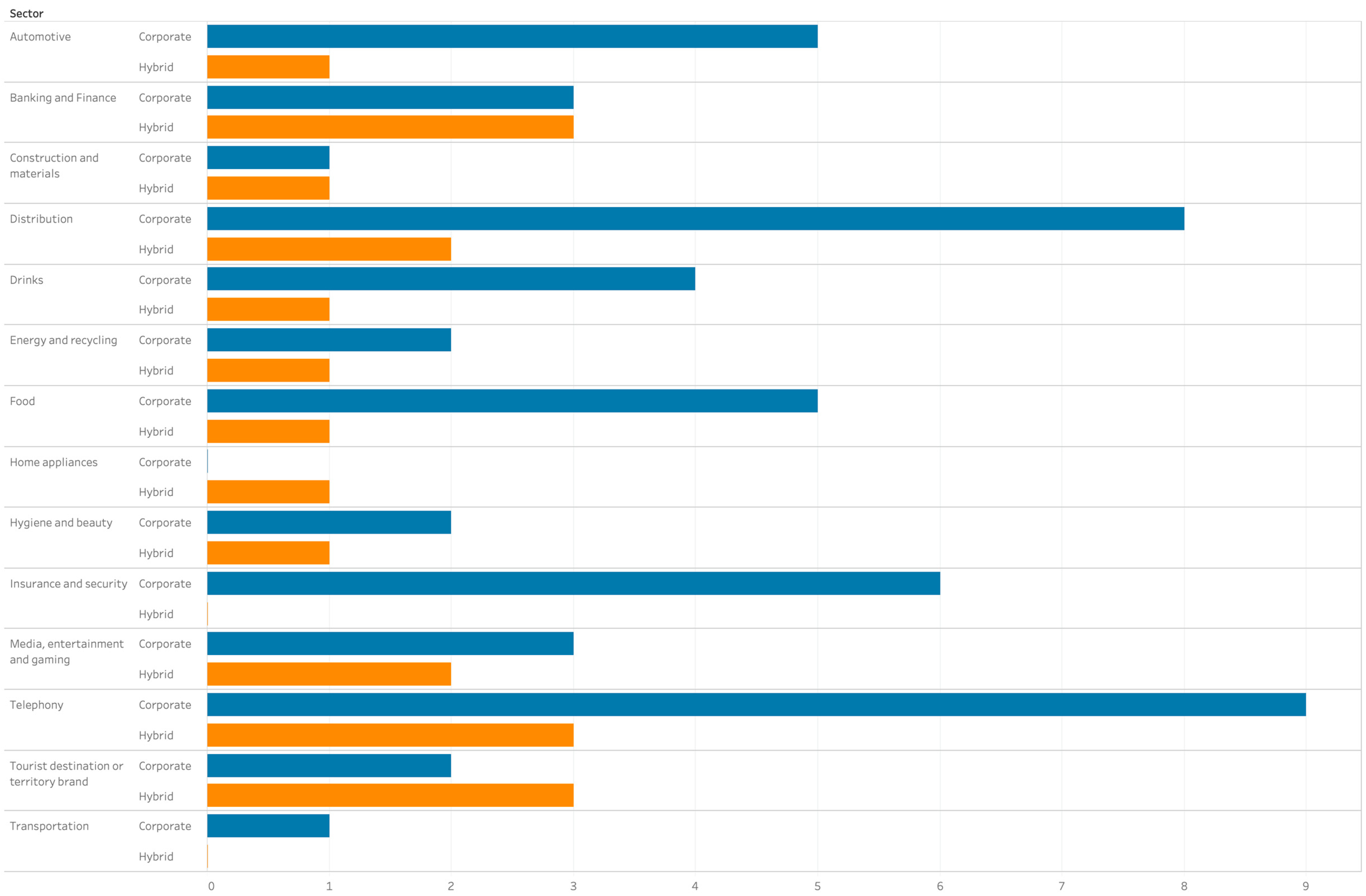

2.2. Sample

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Validity and Reliability

- The content analysis was carried out with all the advertising spots broadcasted by companies in the targeted period;

- There was a representative sample of commercials from different sectors. Therefore, the study does not impose any sample frame bias, regarding a certain advertising style or kind of resource;

- The application of statistical analysis added value and increased the robustness of the results.

3. Results

4. Discussion

- -

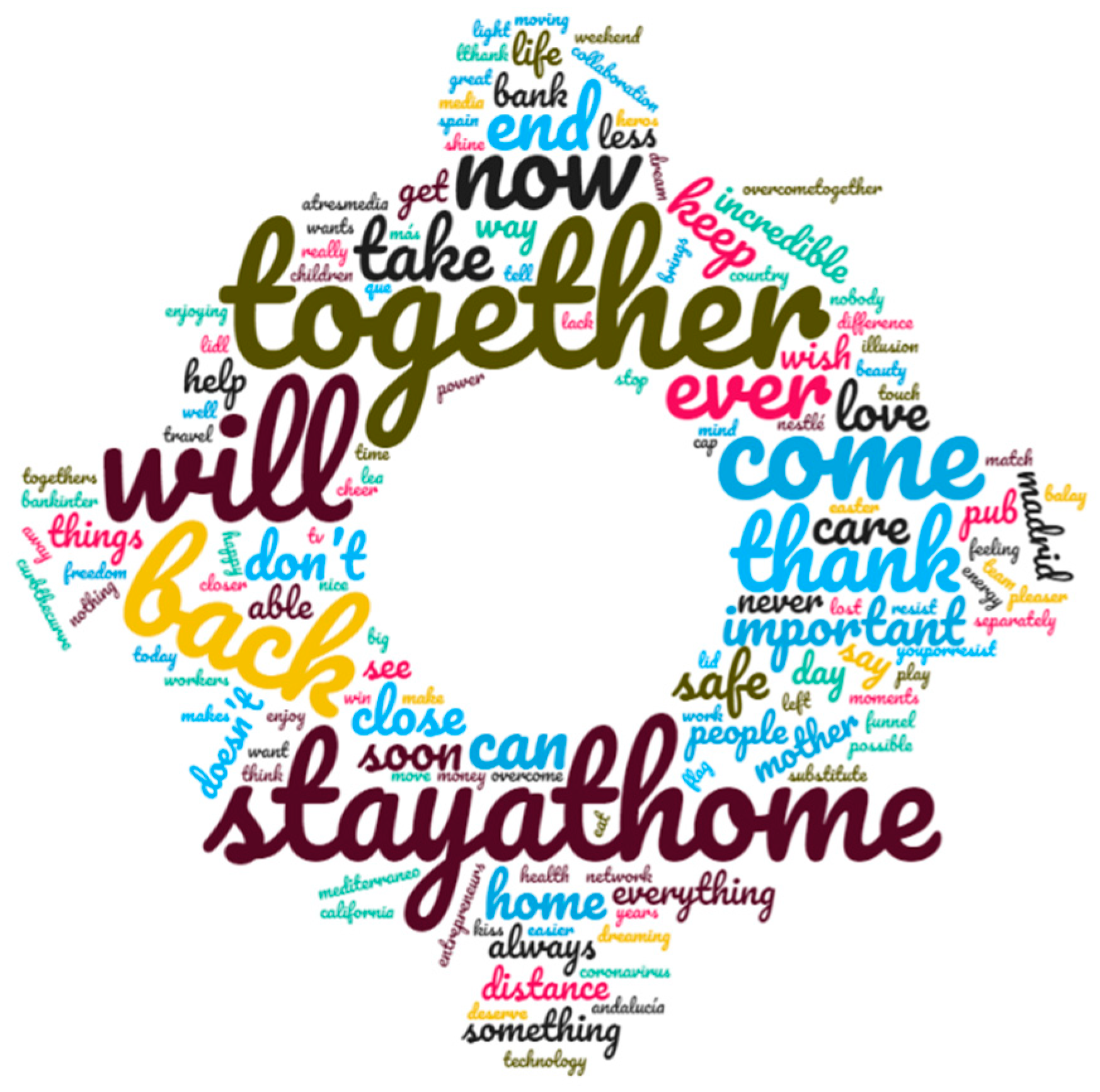

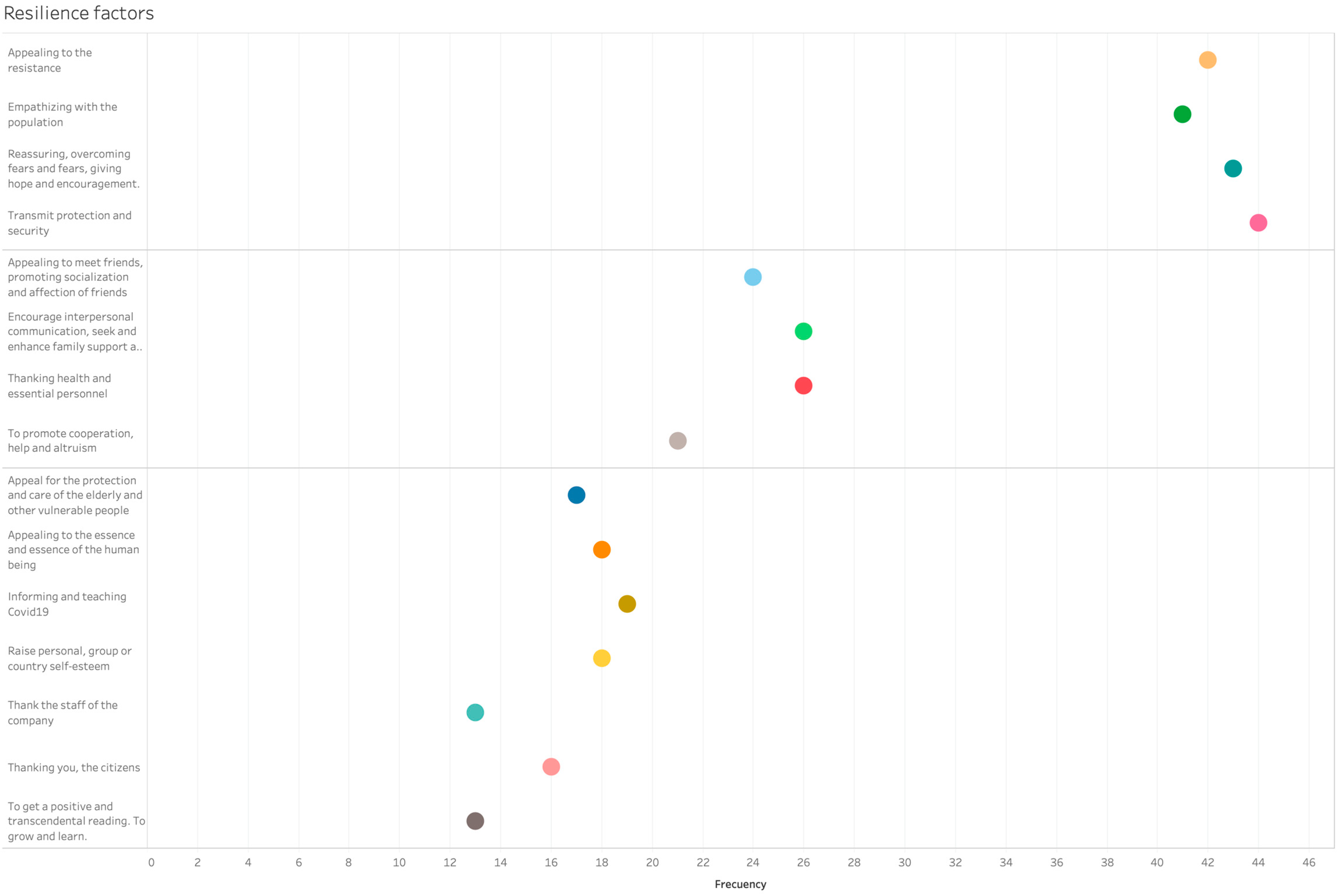

- Dissuasive messages, such as “stay at home”, focused on the key measures for contention of the disease. This message was built in the line of promoting protection of the self and the collective under the environment of pandemic stress, as seen in studies such as that of Roberts and Veil [17].

- -

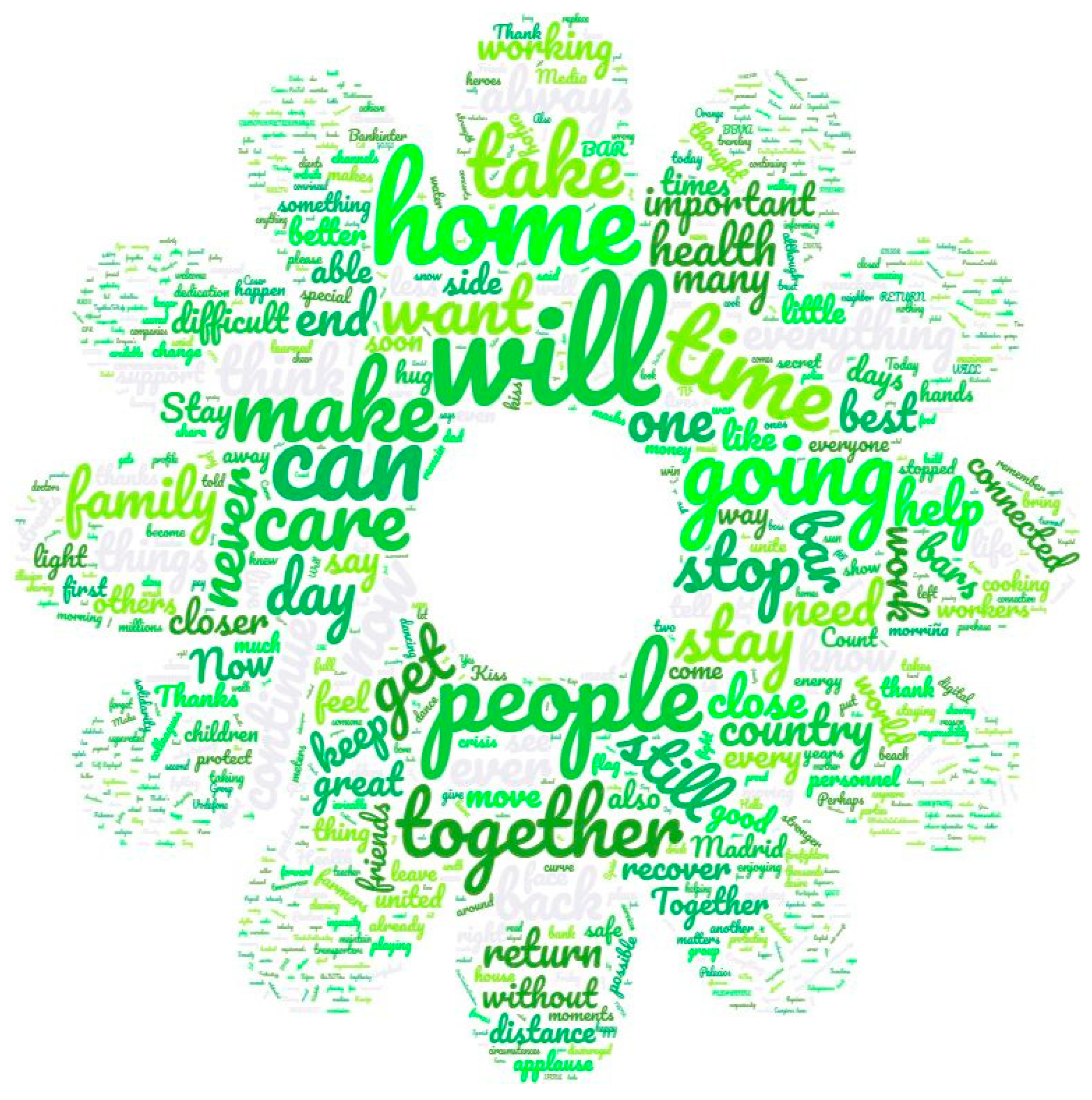

- Messages to overcome fears and to foster hopes, such as “everything will be fine”, increasing the feeling of security and protection. This issue has been pointed out by Reynolds and Seeger [21], regarding crisis communication management; by Grotberg [34,37], specifically focused on resilience; and by Brooks et al. [6], as linked with stress.

- -

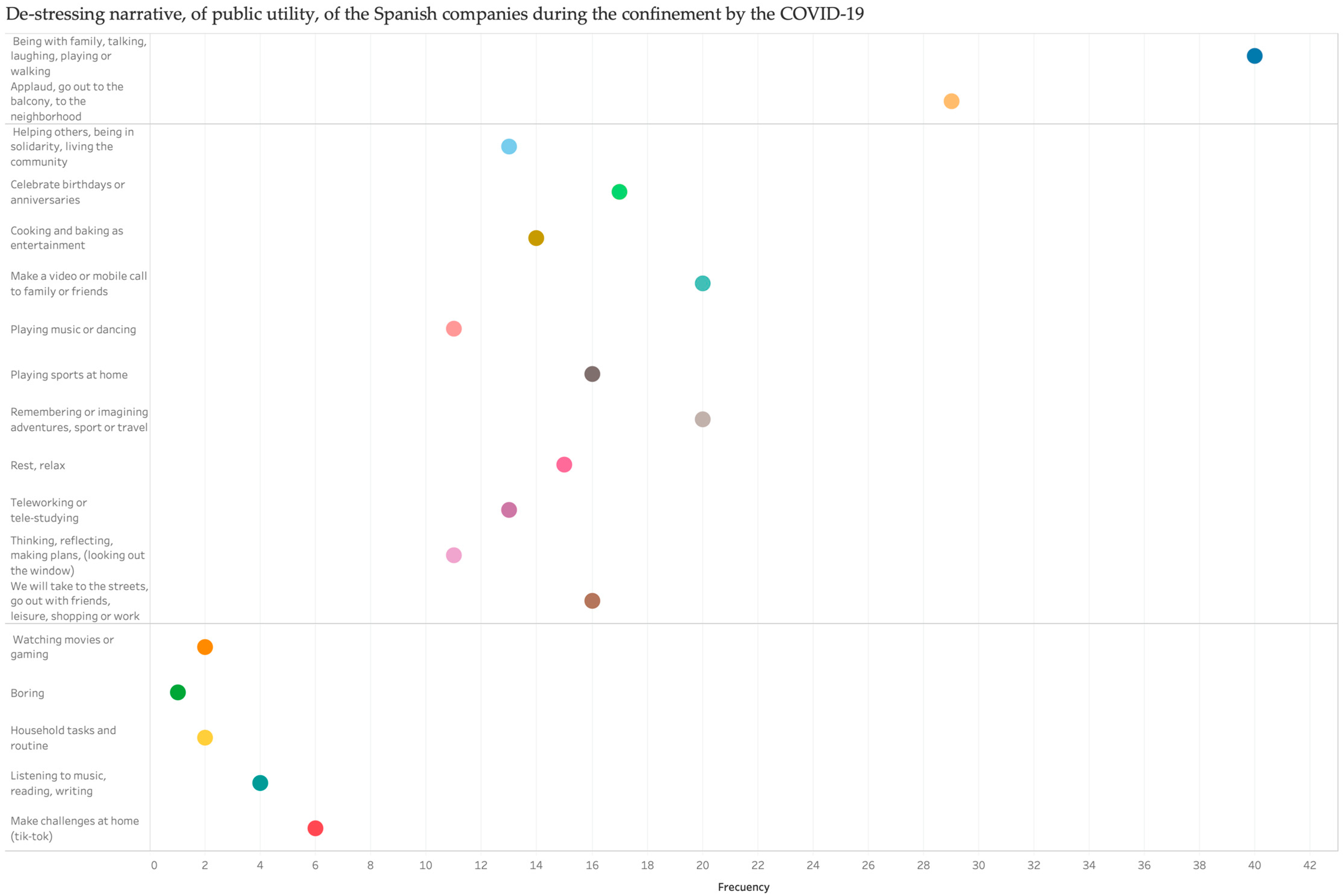

- Ideas to combat frustration and boredom, promoting physical activity such as gymnastics, fitness, or dance. This insight has commonalities with the conclusions reached by Frigon [32]. These proposals are especially useful to manage the levels of stress associated with isolation.

- -

- Proposals for creative, playful, humorous, or challenging activities (e.g., uploading to Tik-Tok) to do at home. Strategies for finding new options, activities, and even routines in traumatic and stressing situations have been stressed as a source of resilience by Connor and Davidson [35], as well as by Goldman and Galea [27].

- -

- -

- -

- Messages whose core is social union, help, and altruism, according to Adger [39].

4.1. Limitations and Future Research Directions

4.2. Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arshad Ali, S.; Baloch, M.; Ahmed, N.; Arshad Ali, A.; Iqbal, A. The outbreak of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)—An emerging global health threat. J. Infect. Public Health 2020, 13, 644–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Du, G.; Duan, Z.; Du, M.; Miao, X.; Tang, Y. Knowledge System Analysis on Emergency Management of Public Health Emergencies. Sustain. Basel 2020, 12, 4410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maital, S.; Barzani, E. The Global Economic Impact of COVID-19: A Summary of Research. Samuel Neaman Institute for National Policy Research. 2020. Available online: https://www.neaman.org.il/EN/Files/Global%20Economic%20Impact%20of%20COVID19.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- De las Heras-Pedrosa, C.; Sánchez-Núñez, P.; Peláez, J.I. Sentiment Analysis and Emotion Understanding during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain and Its Impact on Digital Ecosystems. Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub. Health 2020, 17, 5542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Miao, M.; Lim, J.; Li, M.; Nie, S.; Zhang, X. Is Lockdown Bad for Social Anxiety in COVID-19 Regions? A National Study in The SOR Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub. Health 2020, 17, 4561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, R. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Sánchez, P.P.; Vaccaro Witt, G.F.; Cabrera, F.E.; Jambrino-Maldonado, C. The Contagion of Sentiments during the COVID-19 Pandemic Crisis: The Case of Isolation in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub. Health 2020, 17, 5918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 40dB El País. Estudio de la Crisis del Coronavirus II. Available online: https://40db.es/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Estudio-sobre-la-crisis-del-coronavirus-II-El-Pa%C3%ADs.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2020).

- Lyu, J.C. How young chinese depend on the media during public health crises? A comparative perspective. Public Relat. Rev. 2012, 38, 799–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, M.; Wang, X. Using Social Media to Mine and Analyze Public Opinion Related to COVID-19 in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub. Health 2020, 17, 2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maal, M.; Wilson-North, M. Social media in crisis communication—The “do’s” and “don’ts”. Int. J. Disaster Resil. Built Environ. 2019, 10, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De las Heras-Pedrosa, C.; Rando-Cueto, D.; Jambrino-Maldonado, C.; Paniagua-Rojano, F.J. Exploring the Social Media on the Communication Professionals in Public Health. Spanish Official Medical Colleges Case Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub. Health 2020, 17, 4859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garret, L. COVID-19: The medium is the message. Lancet 2020, 395, 942–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Beltrán, F. La pandemia acelera y transforma los procesos de cambio comunicativos. adComun. Rev. Cient. Estrateg. Tend. Innov. Comun. 2020, 20, 381–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Report of the Review Committee on the Functioning of the International Health Regulations (2005) in Relation to Pandemic (H1N1) 2009; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011; pp. 1–180. [Google Scholar]

- Glick, D.C. Risk Communication for Public Health Emergencies. Annu. Rev. Publ. Health 2007, 28, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, H.; Veil, S.R. Health literacy and crisis: Public relations in the 2010 egg recall. Public Relat. Rev. 2016, 42, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellnow, T.L.; Ulmer, R.R.; Seeger, M.W.; Littlefield, R.S. Effective Risk Communication: A Message-Centered Approach; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Conrow, E.H.; Pohlmann, L.D. Effective Risk Management: Some Keys to Success. INSIGHT 2004, 6, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, T.; Holladay, S.J. Comparing apology to equivalent crisis response strategies: Clarifying apology’s role and value in crisis communication. Public Relat. Rev. 2008, 34, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, B.W.; Seeger, M. Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication as an Integrative Model. J. Health Commun. 2005, 10, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodin, P.; Ghersetti, M.; Odén, T. Disentangling rhetorical subarenas of public health crisis communication: A study of the 2014–2015 Ebola outbreak in the news media and social media in Sweden. J. Conting Crisis Manag. 2019, 37, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renn, O. Risk Governance. Coping with Uncertainty in a Complex. World; Earthscan: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wahlberg, A.A.F.; Sjoberg, L. Risk perception and the media. J. Risk Res. 2000, 3, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirkkonen, P.; Luoma-aho, V. Online authority communication during an epidemic: A Finnish example. Public Relat. Rev. 2011, 37, 172–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, M. Lessons for Crisis Communication on Social Media: A Systematic Review of What Research Tells the Practice. Int. J. Strat. Commun 2018, 12, 526–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldmann, E.; Galea, S. Mental health consequences of disasters. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covello, V.T. Risk communication, the West Nile virus epidemic, and bioterrorism: Responding to the communication challenges posed by the intentional or unintentional release of a pathogen in an urban setting. J. Urban. Health Bull. New York Acad. Med. 2001, 78, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vázquez-Sande, P.; García-Abad, L.; Pineda-Martínez, P. Comunicación interna y crisis reputacional. El caso de la Universidad Rey Juan Carlos. Rev. Lat. De Comun. Soc. 2019, 74, 1748–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, F.H.; Friedman, M.J.; Watson, P.J.; Byrne, C.M.; Diaz, E.; Kaniasty, K. 60,000 Disaster Victims Speak: Part I. An Empirical Review of the Empirical Literature, 1981–2001. Psychiatry Interpers. Biol. Process. 2002, 65, 207–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, G.A.; Gupta, S. Resilience after disaster. In Mental Health and Disasters; Cambridge Univ. Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 145–160. [Google Scholar]

- Frigon, S. Dance, Confinement and Resilient Bodies; Santé et Société; University of Ottawa Press: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, F.H.; Tracy, M.; Galea, S. Looking for resilience: Understanding the longitudinal trajectories of responses to stress. Soc. Sci Med. 2009, 68, 2190–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grotberg, E. Mental Health Functioning in the Human Rights Field: Findings from an International Internet-Based Survey. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0145188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R.T. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety. Depress. Anxiety 2003, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyrulnik, B. Un Merveilleux Malheur; Odile Jacob: Paris, France, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Grotberg, E. The International Resilience Research Project. In Proceedings of the Psychologists Facing the Challenge of a Global Culture with Human Rights and Mental Health, Graz, Austria, 14–18 July 1999; pp. 239–256. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, F. El concepto de resiliencia familiar: Crisis y desafío. Sist. Fam. 1998, 14, 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Adger, W.N. Social and ecological resilience: Are they related? Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2000, 34, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrings, C. Resilience and sustainable development. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2006, 11, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimm, S.L. The complexity and stability of ecosystems. Nature 1984, 307, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. Resilience for Ecosystems, and Incentives for People. Ecol. Appl. 1996, 6, 733–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunderson, L.; Folke, C. Resilience 2011: Leading Transformational Change. Ecol. Soc. 2011, 16, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prime, H.; Wade, M.; Browne, D.T. Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. AM PSYCHOL 2020, 75, 631–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivares, F. Black Brands (in the Age of Transparency); Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Huoston, J.B.; Spialek, M.L.; Cox, J.; Greenwood, M.M.; First, J. The Centrality of Communication and Media in Fostering Community Resilience. Am. Behav. Sci. 2015, 59, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xifra, J. Comunicación corporativa, relaciones públicas y gestión del riesgo reputacional en tiempos del Covid-19. El Prof. De La Inf. 2020, 29, e290220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledingham, J.A.; Bruning, S.D. Relationship management in public relations: Dimensions of an organization-public relationship. Public Relat. Rev. 1998, 24, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelman Special Report: Trust and the Coronavirus. Available online: https://www.edelman.com/sites/g/files/aatuss191/files/2020-03/2020%20Edelman%20Trust%20Barometer%20Coronavirus%20Special%20Report_0.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Barlovento Comunicación El Consumo de Televisión Durante el Estado de Alarma. Available online: https://www.barloventocomunicacion.es/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/INFORME-BARLOVENTO-BALANCE-DEL-CONSUMO-DE-TV-DURANTE-EL-ESTADO-DE-ALARMA.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- El español El Consumo de Televisión se Dispara un 67% el Primer fin de Semana en Casa Por el Coronavirus. Available online: https://www.elespanol.com/invertia/medios/20200316/consumo-television-dispara-primer-semana-casa-coronavirus/475203011_0.html (accessed on 29 July 2020).

- Europa Press Marzo se Convierte en el Mes de Mayor Consumo de TV en España Desde que Hay Registros, según un estudio 2020. Available online: https://www.europapress.es/sociedad/noticia-marzo-convierte-mes-mayor-consumo-tv-espana-hay-registros-estudio-20200331144158.html (accessed on 29 July 2020).

- Europa Press Abril Marca un Récord Histórico Mensual de Consumo Televisivo: 5 horas y 2 Minutos Diarios por Persona 2020. Available online: https://www.europapress.es/sociedad/noticia-abril-marca-record-historico-mensual-consumo-televisivo-horas-minutos-diarios-persona-20200501122200.html (accessed on 29 July 2020).

- Europa Press El Consumo Televisivo de los españoles en Mayo fue de 4 Horas y 20 Minutos Diarios por Persona, 37 Minutos Más. Available online: https://www.europapress.es/sociedad/noticia-consumo-televisivo-espanoles-mayo-fue-horas-20-minutos-diarios-persona-37-minutos-mas-20200601114541.html (accessed on 29 July 2020).

- UTECA Barómetro Sobre la Percepción Social de la Televisión en Abierto. Available online: https://uteca.tv/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/INFORME-BAR%C3%93METRO-SOBRE-LA-PERCEPCI%C3%93N-SOCIAL-DE-LA-TV-EN-ABIERTO.pdf (accessed on 29 July 2020).

- Kantar COVID-19 Barometer. Available online: https://www.kantar.com/campaigns/covid-19-barometer (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Somos Marketing La Importancia de la Publicidad en Tiempos de Coronavirus. Available online: https://somosmarketing.lasprovincias.es/tendencias/la-importancia-de-la-publicidad-en-tiempos-de-coronavirus/ (accessed on 29 July 2020).

- Berelson, B. Content Analysis in Communications Research; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, J.D.; McAllister, C.; Grinnell, L.D.; Walters, K.G.; Appunn, F. Applying Constant Comparative Method with Multiple Investigators and Inter-Coder Reliability. Qual. Rep. 2016, 21, 26–42. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Graebner, M.E. Theory Building from Cases: Opportunities and Challenges. Acad Manag. J. 2007, 50, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y. How Social Media Is Changing Crisis Communication Strategies: Evidence from the Updated Literature. J. Conting. Crisis Manag. 2016, 26, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| The Expected Role of Brands through Their Advertising | Percentage of the Spanish Population That Agrees with This Information |

|---|---|

| Advertising should show how companies can be useful in the new daily life | 83% |

| Advertising should inform your efforts to confront the situation | 81% |

| Advertising should use a reassuring tone | 79% |

| Do not take advantage of the coronavirus to promote the brand | 75% |

| Providing a positive perspective | 70% |

| Communicating brand values | 62% |

| N° | Variable | Categories and Values |

|---|---|---|

| 2 MED | Communication media | Generalist free-to-air televisions (TV1, La 2, Antena 3, La Sexta, Telecinco, Cuatro) |

| 3 SEC | Duration of the advertisement | Seconds |

| 5 BRA | Brand | Product brand name |

| 6 SET | Sector of activity | 1. Food |

| 2. Drinks | ||

| 3. Distribution | ||

| 4. Energy and recycling | ||

| 5. Automotive | ||

| 6. Telephony | ||

| 7. Hygiene and beauty | ||

| 8. Banking and finance | ||

| 9. Insurance and security | ||

| 10. Tourist destination or territory brand | ||

| 11. Media, entertainment, and gaming | ||

| 12. Home appliances | ||

| 13. Construction and materials | ||

| 14. Transportation | ||

| 7 TIP | Type of message | 1. Corporate and institutional or image |

| 2. Product, service, or sales | ||

| 3. Hybrid | ||

| 8 SLO | Advertisement slogan | The slogan or claim is registered |

| 9 TXT | Full text of the advertisement | The full text is recorded |

| 10 TON | Tone | Very positive |

| Positive | ||

| Realistic | ||

| Negative | ||

| Very negative | ||

| 11 EMO | Emotional burden | Very emotional |

| Emotional | ||

| Little emotional | ||

| Rather emotional | ||

| Not at all emotional | ||

| 12 OFF | Voice over | Text overprinting |

| Woman | ||

| Man | ||

| Girl or boy | ||

| Elderly person | ||

| 13 EST | Stress factors. Factors and coping strategies | 1. Rest, relax |

| 2. Get bored | ||

| 3. Thinking, reflecting, planning, looking out the window | ||

| 4. Watching movies or gaming | ||

| 5. Listening to music, reading, writing | ||

| 6. Playing music or dancing | ||

| 7. Cooking and baking as entertainment | ||

| 8. Being with family, talking, laughing, playing, or walking | ||

| 9. We will take to the streets, go out with friends, leisure, shopping, or work | ||

| 10. Household tasks and routine | ||

| 11. Teleworking or tele-studying | ||

| 12. Clap your hands, go out to the balcony, to the neighbourhood | ||

| 13. Helping others, being in solidarity, living the community | ||

| 14. Make a video or mobile call to family or friends | ||

| 15. Playing sports at home | ||

| 16. Remembering or imagining adventures, sport, or travel | ||

| 17. Doing challenges at home (e.g., using tik-tok) | ||

| 18. Celebrate birthdays or anniversaries | ||

| 14 RES | Resilience: Sources of Resilience | 1. Appealing to the resistance |

| 2. Reassuring, overcoming fears and fears, giving hope and encouragement. | ||

| 3. Transmit protection and safety | ||

| 4. Thank the health and essential personnel | ||

| 5. Thanking the company’s staff | ||

| 6. Thanking you, the citizens | ||

| 7. Informing and doing pedagogy regarding COVID-19 | ||

| 8. Raise personal, group, or country self-esteem | ||

| 9. Get a positive and transcendental reading. To grow and learn. | ||

| 10. To promote co-operation, help, and altruism | ||

| 11. Encourage interpersonal communication, seek and enhance family support and affection | ||

| 12. Appealing to meet friends, promoting socialization and affection of friends | ||

| 13. Empathizing with the population | ||

| 14. Appeal to the essence and essence of the human being | ||

| 15. Appeal for the protection and care of the elderly and other vulnerable people |

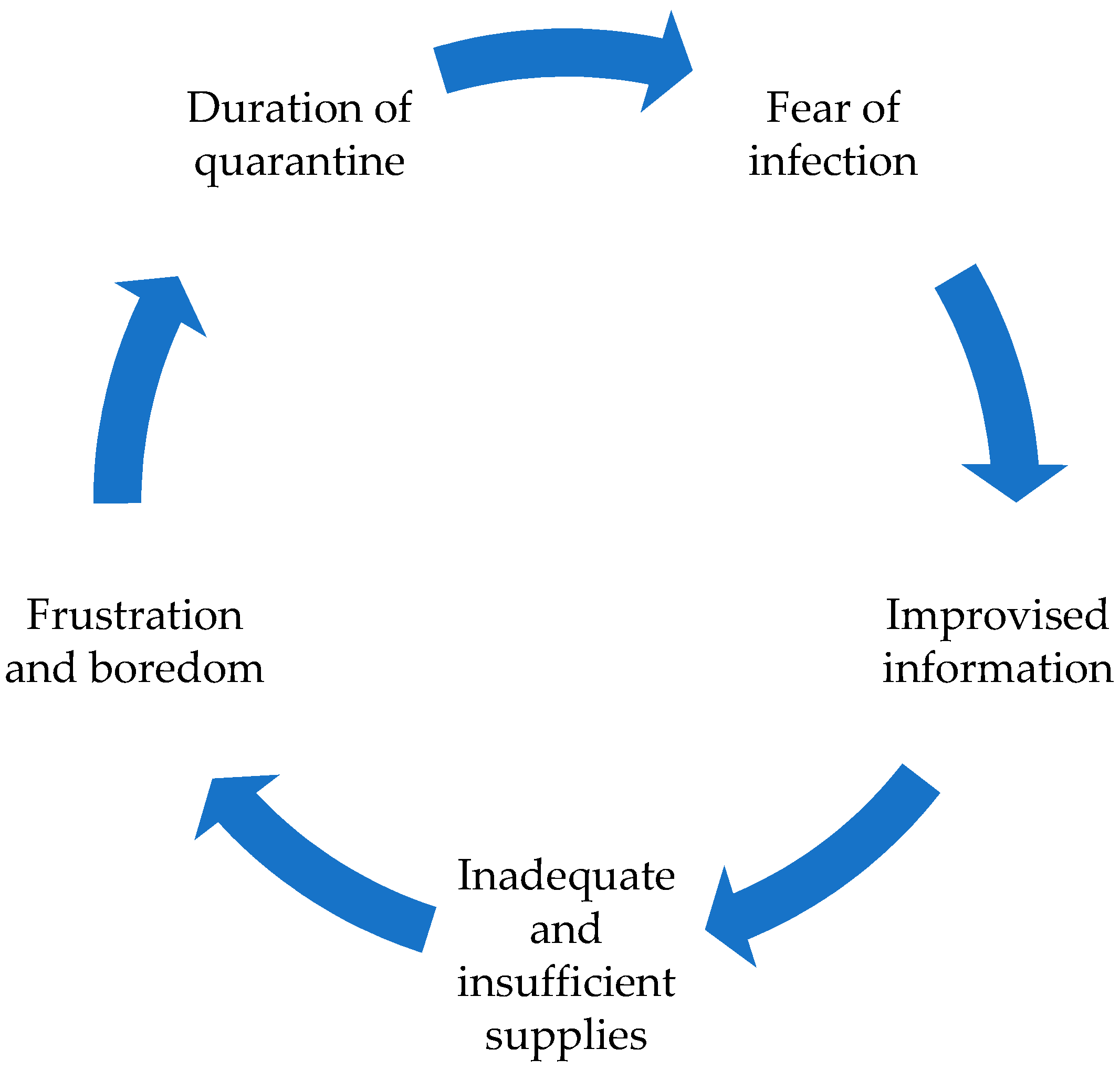

| Stress Factors during Confinement | De-Stressing Narratives of Public Utility from Spanish Companies and Brands during the Confinement Due to COVID-19 |

|---|---|

| Duration of quarantine | “It will all be over soon”. “Our scientists are working to find a solution soon”. “Soon it will be back to normal”. “With occupations and distractions, time goes by sooner”. |

| Fear of infection | “At home you are safe”. “Don’t go out if you don’t have to”. “Be very careful”. “Follow the rules and recommendations”. |

| Inadequate and insufficient supplies | “We work to guarantee the supply of essential goods to Spanish society”. “We work day and night so that you don’t lack anything”. “We are at your service. |

| Improvised information | “We keep you informed”. “Use masks, gels and social distance”. |

| Sources of Resilience | Resilient Narratives of Public Utility from Spanish Companies and Brands during the Confinement Due to COVID-19 | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Appealing to the resistance | “Resist. Stay. Hold on. It is what it touches. Take charge” |

| 2 | Reassuring, overcoming fears and fears, giving hope and encouragement. | “Don’t worry”. “You are not alone”. “Normality will soon return”. “There is less left”. “Everything will be fine. “Everything will be like before”. “There will be time to do everything”. “We will go back to doing the life of before” |

| 3 | Transmit protection and safety | “We are here”. “We work for you”. “Together (we and you) and United”. “You are Safe” |

| 4 | Thank the health and essential personnel | “Come out to the balcony and applaud our health heroes, policemen and essential professions” |

| 5 | Thanking the company’s staff | “Thanks to you, our workers”. “Our workers are also heroes and essential” |

| 6 | Thanking you, the citizens | “Thank you for staying home”. “You are a hero too. “You have our admiration” |

| 7 | Informing and doing pedagogy regarding COVID-19 | “Stay at home”. “Physical distance, hand washing and hydroalcoholic gel”. “Follow the recommendations of the authorities” |

| 8 | Raise personal, group, or country self-esteem | “You are amazing”. “You are extraordinary”. “We are unique”. “We are a great country”. |

| 9 | Get a positive and transcendental reading. To grow and learn. | “We realized that we had to stop”. “We were not on the right track”. “There is no evil that does not come from good”. “Something has to change”. “Reflect. Grow up. Think. Change”. “Value more what you have” |

| 10 | To promote co-operation, help, and altruism | “Helping makes you feel good”. “Help your neighbours, those who are alone and those who need it most”. “Think about the others”. “Think of the other”. |

| 11 | Encourage interpersonal communication, seek and enhance family support and affection | “Talk to your family”. “Lean on others”. “Create bonds with your children, partner and parents”. “Do not distance yourself emotionally from them: make a video call, remember or imagine a re-encounter” |

| 12 | Appealing to meet friends, promoting socialization and affection of friends | “Talk to your friends.” “Lean on them”. “Keep the bonds of affection.” “Don’t distance yourself emotionally from them: video calls with friends” |

| 13 | Empathizing with the population | “We understand you”. “We are with you: we are part of the” “We “. “We know what you are going through”. “We, the companies, take care of it”. “It doesn’t have to be easy for you”. “We row in the same direction”. “We feel identified. “Your problems are our problems” |

| 14 | Appeal to the essence and essence of the human being | “Life. Health. Care. Protection. Affection”. “The small things”. “The small gestures”. “The simple life”. “The simplicity”. “The small pleasures”. “Human being”. “To be united, to create and to maintain the emotional bonds” |

| 15 | Appeal for the protection and care of the elderly and other vulnerable people | “Our elderly, people with disabilities and children need you: they are the most vulnerable” |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Olivares-Delgado, F.; Iglesias-Sánchez, P.P.; Benlloch-Osuna, M.T.; Heras-Pedrosa, C.d.l.; Jambrino-Maldonado, C. Resilience and Anti-Stress during COVID-19 Isolation in Spain: An Analysis through Audiovisual Spots. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8876. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238876

Olivares-Delgado F, Iglesias-Sánchez PP, Benlloch-Osuna MT, Heras-Pedrosa Cdl, Jambrino-Maldonado C. Resilience and Anti-Stress during COVID-19 Isolation in Spain: An Analysis through Audiovisual Spots. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(23):8876. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238876

Chicago/Turabian StyleOlivares-Delgado, Fernando, Patricia P. Iglesias-Sánchez, María Teresa Benlloch-Osuna, Carlos de las Heras-Pedrosa, and Carmen Jambrino-Maldonado. 2020. "Resilience and Anti-Stress during COVID-19 Isolation in Spain: An Analysis through Audiovisual Spots" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 23: 8876. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238876

APA StyleOlivares-Delgado, F., Iglesias-Sánchez, P. P., Benlloch-Osuna, M. T., Heras-Pedrosa, C. d. l., & Jambrino-Maldonado, C. (2020). Resilience and Anti-Stress during COVID-19 Isolation in Spain: An Analysis through Audiovisual Spots. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(23), 8876. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238876