Emotional Intelligence and the Different Manifestations of Bullying in Children

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. EI and Its Measurement in the Child Population

1.2. EI and Victimisation in Bullying

1.3. Objectives and Hypothesis

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Instruments

3. Results

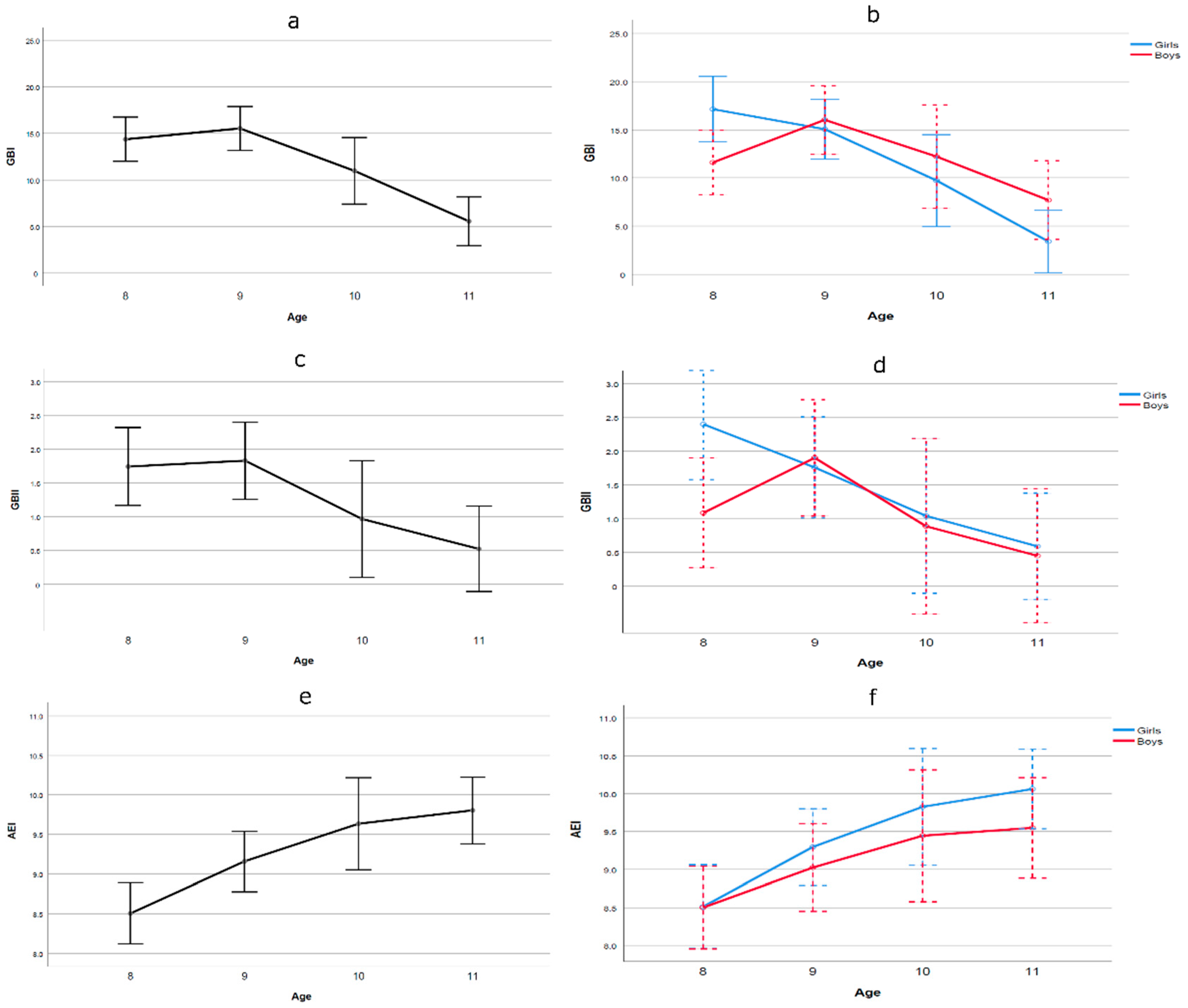

3.1. Age and Gender

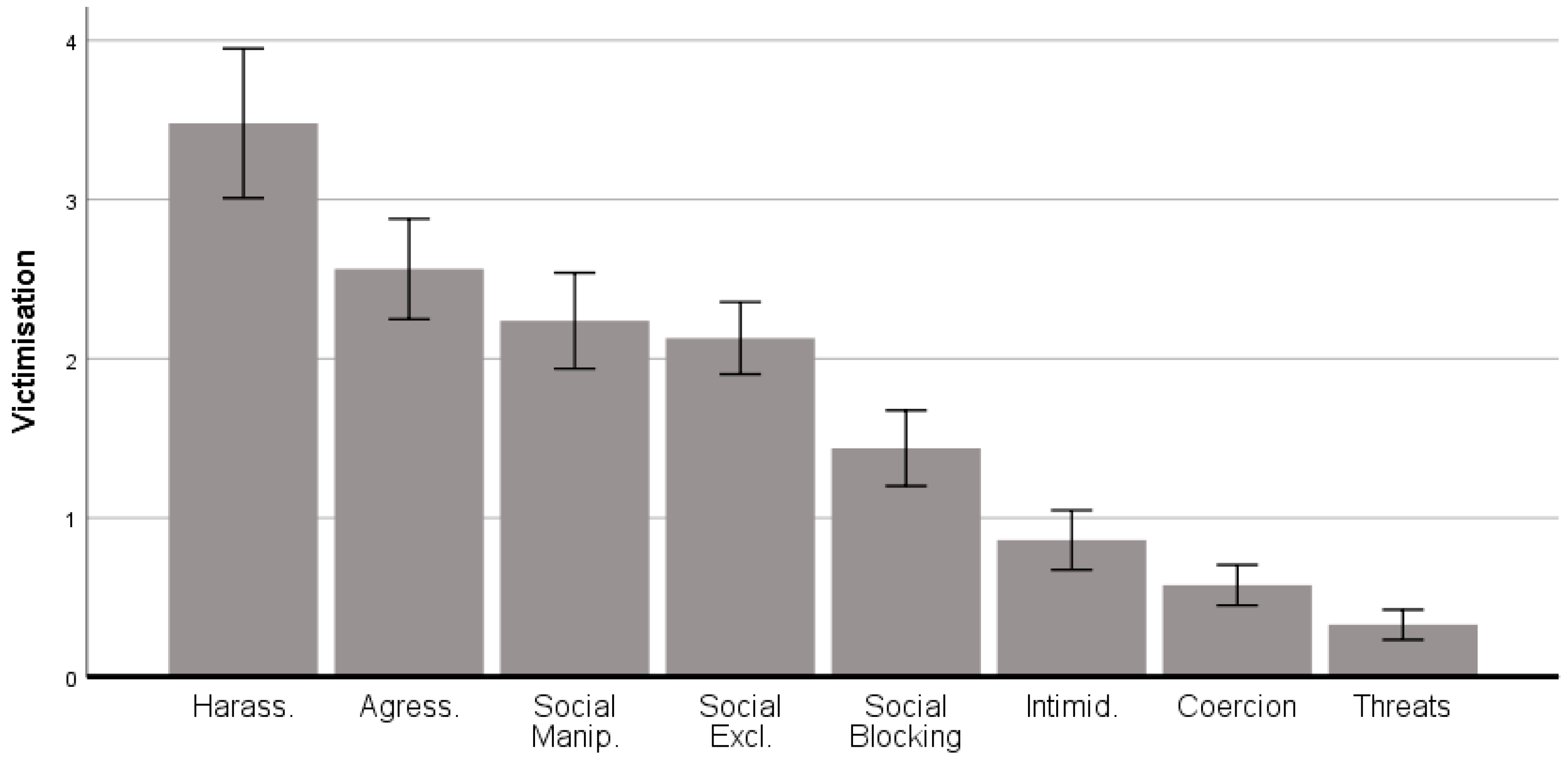

3.2. Type of Victimisation and AEI

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sastre, S.; Artola, T.; Alvarado, J.M. Emotional intelligence in elementary school children. EMOCINE, a novel assessment test based on the interpretation of cinema scenes. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piñuel, I.; Oñate, A. AVE: Acoso y Violencia Escolar; TEA: Madrid, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Antonio-Aguirre, I.; Esnaola, I.; Rodríquez-Fernández, A. La medida de la inteligencia emocional en el ámbito psicoeducativo [The measurement of emotional intelligence in the psycho-educational field]. Rev. Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2017, 88, 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Keefer, K.V. Self-report assessments of emotional competencies: A critical look at methods and meanings. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 2015, 33, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Extremera-Pacheco, N.; Fernández-Berrocal, P. Una guía práctica de los instrumentos actuales de evaluación de la inteligencia emocional [A practical guide to current emotional intelligence assessment instruments]. In Manual de Inteligencia Emocional; Mestre, J.M., Fernández Berrocal, P., Eds.; Pirámide: Madrid, Spain, 2007; pp. 99–122. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-On, R. The Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i); Multi-Healt System Technical Manual: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, R.K.; Sawaf, A.C. Executive EQ: Emotional Intelligence in Leadership and Organisation; Penguin Puttam Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Goleman, D. Emotional Intelligence; Bantam: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Goleman, D. Working with Emotional Intelligence; Bantam: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Petrides, K.V.; Mavroveli, S. Theory and applications of trait emotional intelligence. Psychology 2018, 23, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Extremera-Pacheco, N.; Fernández-Berrocal, P. La inteligencia emocional en el contexto educativo: Hallazgos científicos de sus efectos en el aula [Emotional intelligence in the educational context: Scientific findings of its effects in the classroom]. Rev. Educ. 2003, 332, 97–116. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, J.D.; Salovey, P. What is Emotional Intelligence? In Emotional Development and Emotional Intelligence: Implications for Educators; Salovey, P., Sluyter, D., Eds.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, J.D.; Caruso, D.R.; Salovey, P. Emotional intelligence meets traditional standards for an intelligence. Intelligence 1999, 27, 267–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J.D. MSCEIT: Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test; Multi-Health Systems: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, J.D. The Mayer–Salovey–Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test–Youth Version (MSCEIT-YV), Research Version; Multi Health Systems: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, J.D.; Salovey, P.; Caruso, D.R. Emotional intelligence: New ability or eclectic traits? Am. Psychol. 2008, 63, 503–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J.D.; Salovey, P.; Caruso, D.R. The validity of the MSCEIT: Additional analyses and evidence. Emot. Rev. 2012, 4, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J.D.; Caruso, D.R.; Salovey, P. The ability model of emotional intelligence: Principles and updates. Emot. Rev. 2016, 8, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salovey, P.; Mayer, J.D. Emotional intelligence. Imagin. Cogn. Pers. 1990, 9, 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.T. Mayer–Salovey–Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT/MEIS) and overall, verbal, and nonverbal intelligence: Meta-analytic evidence and critical contingencies. Pers. Indiv. Differs 2014, 66, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabello, R.; Navarro-Bravo, B.; Latorre, J.M.; Fernández-Berrocal, P. Ability of university-level education to prevent age-related decline in emotional intelligence. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2014, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, O.P.; Gross, J.J. Healthy and unhealthy emotion regulation: Personality processes, individual differences, and life span development. J. Pers. 2004, 72, 1301–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, L.H.; Henry, J.D.; Hosie, J.A.; Milne, A.B. Age, anger regulation and well-being. Aging Ment. Health 2006, 10, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, L.H.; MacLean, R.D.; Allen, R. Age and the understanding of emotions: Neuropsychological and sociocognitive perspectives. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2002, 57, P526–P530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León Rodríguez, D.A.; Sierra-Mejía, H. Desarrollo de la comprensión de las Consecuencias de las emociones [Development of understanding of emotional consequences]. Rev. Lat. Psicol. 2008, 40, 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Cazalla-Luna, N.; Molero, D. Inteligencia emocional percibida, ansiedad y afectos en estudiantes universitarios [Perceived emotional intelligence, anxiety and affect on university students]. Rev. Esp. Orientac. Psicopedag. 2014, 25, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Gomes, R.M.; Sousa-Pereira, A. Influence of age and gender in acquiring social skills in Portuguese preschool education. Psychology 2014, 5, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido Acosta, F.; Herrera Clavero, F. Relations between performance and emotional inteligence in secondary education. Tend. Pedagóg. 2018, 31, 165–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivers, S.E.; Brackett, M.A.; Reyes, M.R.; Mayer, J.D.; Caruso, D.R.; Salovey, P. Measuring emotional intelligence in early adolescence with the MSCEIT-YV: Psychometric properties and relationship with academic performance and psychosocial functioning. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 2012, 30, 344–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Berrocal, P.; Extremera, N.; Palomera, R.; Ruiz-Aranda, D.; Salguero, J.M. Test de Inteligencia Emocional de la Fundación Botín Para Adolescentes (TIEFBA); Fundación Botín: Santander, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zych, I.; Ttofi, M.M.; Farrington, D.P. Empathy and callous–unemotional traits in different bullying roles: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma Violence Abus. 2019, 20, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olweus, D. Bullying at school: Tackling the problem. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. OECD Obs. 2001, 225, 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Orpinas, P.; Home, A.M. Bullying Prevention: Creating a Positive School Climate and Developing Social Competence; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P.K.; Brain, P. Bullying in schools: Lessons from two decades of research. Aggress. Behav. 2000, 26, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaigordobil, M.; Oñederra, J.A. Inteligencia emocional en las víctimas de acoso escolar y en los agresores [Emotional intelligence in victims of school bullying and in aggressors]. Eur. J. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 3, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkinos, C.M.; Kipritsi, E. The relationship between bullying, victimisation, trait emotional intelligence, self-efficacy and empathy among preadolescents. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2012, 15, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomas, J.; Stough, C.; Hansen, K.; Downey, L.A. Brief report: Emotional intelligence, victimisation and bullying in adolescents. J. Adolesc. 2012, 35, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavroveli, S.; Sánchez-Ruiz, M.J. Trait emotional intelligence influences on academic achievement and school behaviour. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2011, 81, 112–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schokman, C.; Downey, L.A.; Lomas, J.; Wellham, D.; Wheaton, A.; Simmons, N.; Stough, C. Emotional intelligence, victimisation, bullying behaviours and attitudes. Learn Individ Differ 2014, 36, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, R.S.; Gross, A.M. Childhood bullying: Current empirical findings and future directions for research. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2004, 9, 379–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishnoi, D. School bullying and victimisation in adolescents. Indian J. Health Wellbeing 2018, 9, 413–416. [Google Scholar]

- Boulton, M.J.; Underwood, K. Bully/victim problems among middle school children. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 1992, 62, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camodeca, M.; Goossens, F.A.; Terwogt, M.M.; Schuengel, C. Bullying and victimisation among school-age children: Stability and links to proactive and reactive aggression. Soc. Dev. 2002, 11, 332–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garmy, P.; Vilhjálmsson, R.; Kristjánsdóttir, G. Bullying in school-aged children in Iceland: A cross-sectional study. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2018, 38, e30–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olweus, D. Bully/victim problems in school: Facts and intervention. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 1997, 12, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheithauer, H.; Hayer, T.; Petermann, F.; Jugert, G. Physical, verbal, and relational forms of bullying among German students: Age trends, gender differences, and correlates. Aggress. Behav. 2006, 32, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.K.; Madsen, K.C.; Moody, J.C. What causes the age decline in reports of being bullied at school? Towards a developmental analysis of risks of being bullied. Educ. Res. 1999, 41, 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, I.; Smith, P.K. A survey of the nature and extent of bullying in junior/middle and secondary schools. Educ. Res. 1993, 35, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Blanco, A.; Sastre, S.; Artola, T.; Alvarado, J.M. Inteligencia Emocional y Rendimiento Académico: Un Modelo Evolutivo [Emotional Intelligence and Academic Achievement: A Developmental Model]. Rev. Iberoam. Diagn. Eval. 2020, 56, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynie, D.L.; Nansel, T.; Eitel, P.; Crump, A.D.; Saylor, K.; Yu, K.; Simons-Morton, B. Bullies, victims, and bully/victims: Distinct groups of at-risk youth. J. Early Adolesc. 2001, 21, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Berrocal, P.; Ruiz-Aranda, D.; Salguero, J.M.; Palomera, R.; Extremera, N. The Relationship of Botín Foundation’s Emotional Intelligence Test (TIEFBA) With Personal and Scholar Adjustment of Spanish Adolescent. Rev. Psicodidáct. 2018, 23, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alvarado, J.M.; Jiménez-Blanco, A.; Artola, T.; Sastre, S.; Azañedo, C.M. Emotional Intelligence and the Different Manifestations of Bullying in Children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8842. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238842

Alvarado JM, Jiménez-Blanco A, Artola T, Sastre S, Azañedo CM. Emotional Intelligence and the Different Manifestations of Bullying in Children. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(23):8842. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238842

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlvarado, Jesús M., Amelia Jiménez-Blanco, Teresa Artola, Santiago Sastre, and Carolina M. Azañedo. 2020. "Emotional Intelligence and the Different Manifestations of Bullying in Children" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 23: 8842. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238842

APA StyleAlvarado, J. M., Jiménez-Blanco, A., Artola, T., Sastre, S., & Azañedo, C. M. (2020). Emotional Intelligence and the Different Manifestations of Bullying in Children. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(23), 8842. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238842