Patient-Reported Experiences in Accessing Primary Healthcare among Immigrant Population in Canada: A Rapid Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

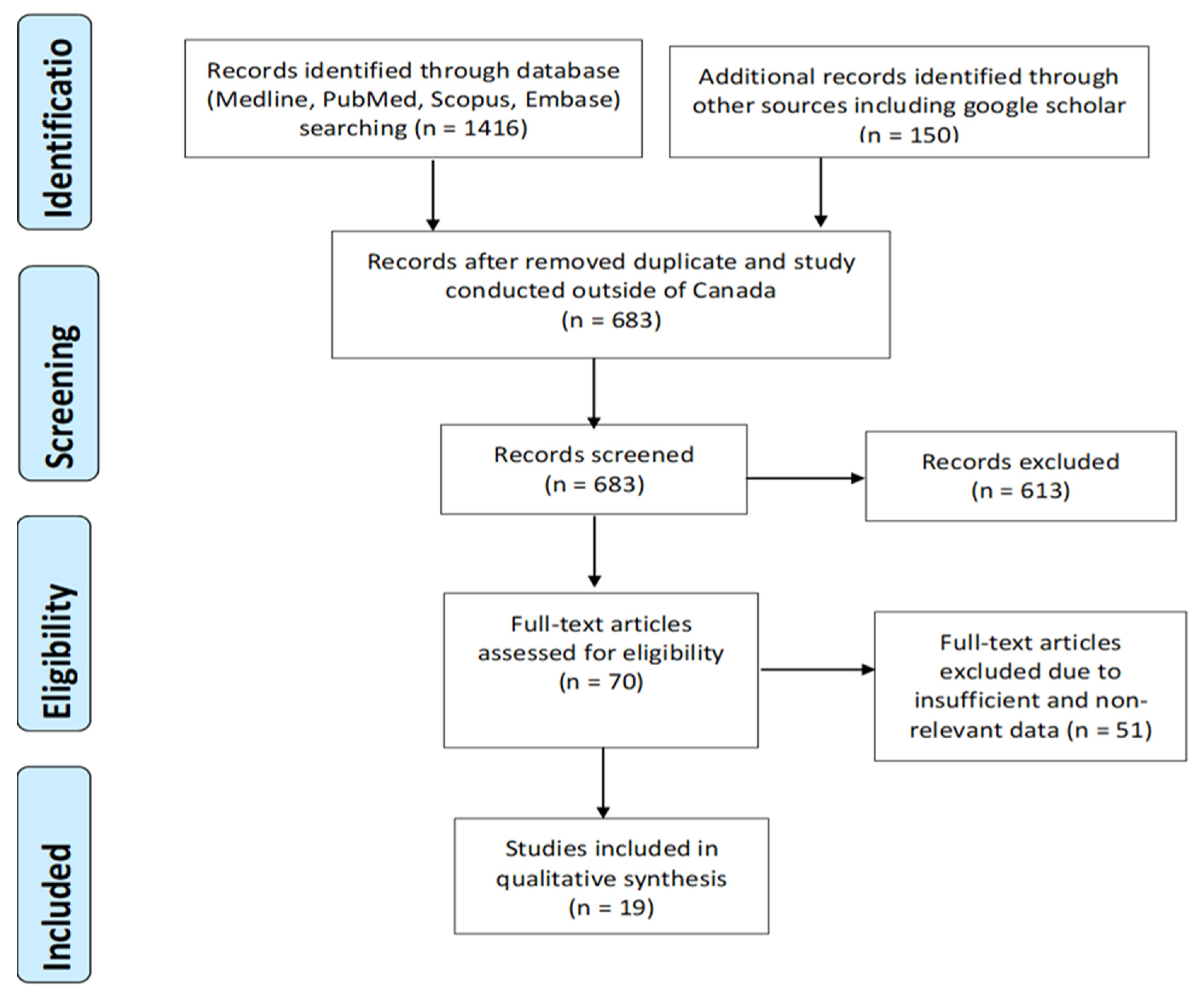

2.1. Search Strategy and Study Selection

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction and Evaluation

2.4. Assessment of Quality and Risk of Bias

3. Results

3.1. Overview of the Selected Study

3.2. Summary of the Studies

3.2.1. Cultural and Linguistic Differences

3.2.2. Socioeconomic Challenges

3.2.3. Health System Structure Factors

3.2.4. Patient–Provider Relationship

4. Discussion

4.1. Overcoming Cultural and Linguistic Differences

4.2. Facing Socioeconomic and Structural Challenges

4.3. Improving Patient–Provider Relationship

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No. | Search terms/limits | Result |

| 1 | Primary Care.mp. or exp Primary Health Care/ | 229,630 |

| 2 | exp Primary Health Care/ or exp Patient Satisfaction/ or exp "Quality of Health Care"/ or Patient Experience.mp. or exp Patient-Centered Care/ | 7,026,134 |

| 3 | 1 and 2 | 197,116 |

| 4 | Immigrant.mp. or exp "Emigrants and Immigrants"/ | 21,250 |

| 5 | 3 and 4 | 727 |

| 6 | limit 5 to english language | 659 |

| 7 | limit 6 to yr="2010 -Current" | 523 |

| 8 | limit 7 to journal article | 508 |

| No. | Search terms/limits | Result |

| 1 | primary health care/ or exp health care delivery/ | 3,300,025 |

| 2 | Experiences.mp. | 237,561 |

| 3 | 1 and 2 | 45,464 |

| 4 | exp immigrant/ | 16,428 |

| 5 | 3 and 4 | 171 |

| 6 | limit 5 to english language | 169 |

| 7 | limit 6 to yr=”2010 -Current” | 121 |

| Author(s) and Year | Selection | Comparability | Exposure/Outcome | Total Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lum, I.D et al., 2016 | *** | ** | *** | 8 |

| Woodgate, R. L. et al., 2017 | *** | ** | *** | 8 |

| Gulati, S. et al., 2011 | **** | ** | *** | 9 |

| Amin, M. et al., 2012 | *** | * | *** | 7 |

| Calvasina, P. et al., 2016 | *** | ** | *** | 8 |

| Cloos, P. et al., 2020 | *** | ** | *** | 8 |

| Harrington, D. et al., 2013 | *** | ** | *** | 8 |

| Hulme, J et al., 2016 | *** | ** | *** | 8 |

| Mumtaz, Z et al., 2014 | *** | * | *** | 7 |

| Corscadden, L et al., 2018 | *** | * | *** | 7 |

| Marshall E. G et al., 2010 | *** | ** | *** | 8 |

| Ou, C.H.K et al., 2017 | *** | * | *** | 7 |

| George, P et al., 2014 | *** | * | *** | 7 |

| Higginbottom, G. M. et al., 2016 | **** | ** | *** | 9 |

| Lee, T.Y. et al., 2014 | *** | ** | *** | 8 |

| Dastjerdi, M. et al., 2012 | *** | ** | *** | 8 |

| Ngwakongnwi E. et al., 2012 | **** | ** | *** | 9 |

| Wang, L. et al., 2015 | *** | * | *** | 7 |

| Pollock, Grace et al., 2012 | *** | * | *** | 7 |

References

- What Is Patient Experience? Available online: https://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/about-cahps/patient-experience/index.html (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Ahmed, F.; Burt, J.; Roland, M. Measuring patient experience: Concepts and methods. Patient 2014, 7, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Quality Board, NHS. NHS Patient Experience Framework. 2018. Available online: https://improvement.nhs.uk/documents/2885/Patient_experience_improvement_framework_full_publication.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- Canadian Institute of Health Information. Experiences with Primary Health Care in Canada. 2009. Available online: https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/cse_phc_aib_en.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- Ahmed, S.; Shommu, N.S.; Rumana, N.; Barron, G.R.; Wicklum, S.; Turin, T.C. Barriers to Access of Primary Healthcare by Immigrant Populations in Canada: A Literature Review. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2016, 18, 1522–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of Canada. Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity: Key Results from the 2016 Census. 2017. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/rt-td/imm-eng.cfm (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- Government of Canada. 2018 Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration. 2019. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/corporate/publications-manuals/annual-report-parliament-immigration-2018/report.html (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- Vang, Z.; Sigouin, J.; Flenon, A.; Gagnon, A. The healthy immigrant effect in Canada: A systematic review. Population Change and Lifecourse Strategic Knowledge Cluster Discussion Paper Series/Un Réseau Stratégique de Connaissances Changements de Population et Parcours de Vie Document de Travail. 2015, Volume 3, p. 4. Available online: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/pclc/vol3/iss1/4 (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- Gushulak, B.D.; Pottie, K.; Hatcher Roberts, J.; Torres, S.; DesMeules, M. Migration and health in Canada: Health in the global village. CMAJ 2011, 183, E952–E958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Maio, F.G.; Kemp, E. The deterioration of health status among immigrants to Canada. Glob. Public Health 2010, 5, 462–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asanin, J.; Wilson, K. “I spent nine years looking for a doctor”: Exploring access to health care among immigrants in Mississauga, Ontario, Canada. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 66, 1271–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setia, M.S.; Quesnel-Vallee, A.; Abrahamowicz, M.; Tousignant, P.; Lynch, J. Access to health-care in Canadian immigrants: A longitudinal study of the National Population Health Survey. Health Soc. Care Community 2011, 19, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salami, B.; Salma, J.; Hegadoren, K. Access and utilization of mental health services for immigrants and refugees: Perspectives of immigrant service providers. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 28, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margulis, A.V.; Pladevall, M.; Riera-Guardia, N.; Varas-Lorenzo, C.; Hazell, L.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Perez-Gutthann, S. Quality assessment of observational studies in a drug-safety systematic review, comparison of two tools: The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale and the RTI item bank. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 6, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lum, I.D.; Swartz, R.H.; Kwan, M.Y.W. Accessibility and use of primary healthcare for immigrants living in the Niagara Region. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 156, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvasina, P.; Lawrence, H.P.; Hoffman-Goetz, L.; Norman, C.D. Brazilian immigrants’ oral health literacy and participation in oral health care in Canada. BMC Oral. Health 2016, 16, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrington, D.W.; Wilson, K.; Rosenberg, M.; Bell, S. Access granted! Barriers endure: Determinants of difficulties accessing specialist care when required in Ontario, Canada. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013, 13, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulme, J.; Moravac, C.; Ahmad, F.; Cleverly, S.; Lofters, A.; Ginsburg, O.; Dunn, S. “I want to save my life”: Conceptions of cervical and breast cancer screening among urban immigrant women of South Asian and Chinese origin. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Kwak, M.J. Immigration, barriers to healthcare and transnational ties: A case study of South Korean immigrants in Toronto, Canada. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, G.; Newbold, K.B.; Lafrenière, G.; Edge, S. Discrimination in the Doctor’s Office: Immigrants and Refugee Experiences. Crit. Soc. Work 2012, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.; Perez, A. Is the wait-for-patient-to-come approach suitable for African newcomers to Alberta, Canada? Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2012, 40, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, Z.; O’Brien, B.; Higginbottom, G. Navigating maternity health care: A survey of the Canadian prairie newcomer experience. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higginbottom, G.M.; Safipour, J.; Yohani, S.; O’Brien, B.; Mumtaz, Z.; Paton, P.; Chiu, Y.; Barolia, R. An ethnographic investigation of the maternity healthcare experience of immigrants in rural and urban Alberta, Canada. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016, 16, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastjerdi, M.; Olson, K.; Ogilvie, L. A study of Iranian immigrants’ experiences of accessing Canadian health care services: A grounded theory. Int. J. Equity Health 2012, 11, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngwakongnwi, E.; Hemmelgarn, B.R.; Musto, R.; Quan, H.; King-Shier, K.M. Experiences of French speaking immigrants and non-immigrants accessing health care services in a large Canadian city. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 3755–3768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, S.; Watt, L.; Shaw, N.; Sung, L.; Poureslami, I.M.; Klaassen, R.; Dix, D.; Klassen, A.F. Communication and language challenges experienced by Chinese and South Asian immigrant parents of children with cancer in Canada: Implications for health services delivery. Pediatric Blood Cancer 2012, 58, 572–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corscadden, L.; Levesque, J.F.; Lewis, V.; Strumpf, E.; Breton, M.; Russell, G. Factors associated with multiple barriers to access to primary care: An international analysis. Int. J. Equity Health 2018, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, T.Y.; Landy, C.K.; Wahoush, O.; Khanlou, N.; Liu, Y.C.; Li, C.C. A descriptive phenomenology study of newcomers’ experience of maternity care services: Chinese women’s perspectives. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, E.G.; Wong, S.T.; Haggerty, J.L.; Levesque, J.F. Perceptions of unmet healthcare needs: What do Punjabi and Chinese-speaking immigrants think? A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2010, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, C.H.K.; Wong, S.T.; Levesque, J.-F.; Saewyc, E. Healthcare needs and access in a sample of Chinese young adults in Vancouver, British Columbia: A qualitative analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2017, 4, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodgate, R.L.; Busolo, D.S.; Crockett, M.; Dean, R.A.; Amaladas, M.R.; Plourde, P.J. A qualitative study on African immigrant and refugee families’ experiences of accessing primary health care services in Manitoba, Canada: It’s not easy! Int. J. Equity Health 2017, 16, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloos, P.; Ndao, E.M.; Aho, J.; Benoît, M.; Fillol, A.; Munoz-Bertrand, M.; Ouimet, M.J.; Hanley, J.; Ridde, V. The negative self-perceived health of migrants with precarious status in Montreal, Canada: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, P.; Terrion, J.; Ahmed, R. Reproductive health behaviour of Muslim immigrant women in Canada. Int. J. Migr. 2014, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesanti, S.R.; Abelson, J.; Lavis, J.N.; Dunn, J.R. Enabling the participation of marginalized populations: Case studies from a health service organization in Ontario, Canada. Health Promot. Int. 2017, 32, 636–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Kim, B.; Choi, E.; Song, Y.; Han, H.R. Knowledge, perceptions, and decision making about human papillomavirus vaccination among Korean American women: A focus group study. Womens Health Issues 2015, 25, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, M.; Johnston, C.; Bever, A. Exploring Health Service Underutilization: A Process Evaluation of the Newcomer Women’s Health Clinic. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2018, 20, 920–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- College of Physicians and Surgeons of Saskatchewan. Patient-Physician Relationships. 2020. Available online: https://www.cps.sk.ca/imis/Documents/Legislation/Policies/GUIDELINE%20-%20Patient%20Physician%20Relationships.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Kirmayer, L.J.; Narasiah, L.; Munoz, M.; Rashid, M.; Ryder, A.G.; Guzder, J.; Hassan, G.; Rousseau, C.; Pottie, K.; CCIRH. Common mental health problems in immigrants and refugees: General approach in primary care. CMAJ 2011, 183, E959–E967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of Canada. Canada’s Health Care System. 2019. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-care-system/reports-publications/health-care-system/canada.html (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- Chiarenza, A.; Dauvrin, M.; Chiesa, V.; Baatout, S.; Verrept, H. Supporting access to healthcare for refugees and migrants in European countries under particular migratory pressure. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathryn Pitkin, D.; Escarce, J.J.; Lurie, N. Immigrants And Health Care: Sources Of Vulnerability. Health Aff. 2007, 26, 1258–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliland, J.A.; Shah, T.I.; Clark, A.; Sibbald, S.; Seabrook, J.A. A geospatial approach to understanding inequalities in accessibility to primary care among vulnerable populations. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowen, S. The Impact of Language Barriers on Patient Safety and Quality of Care. 2015. Available online: http://www.santefrancais.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/SSF-Bowen-S.-Language-Barriers-Study-1.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- Kreps, G.L.; Sparks, L. Meeting the health literacy needs of immigrant populations. Patient Educ. Couns. 2008, 71, 328–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macpherson, D.W.; Gushulak, B.D.; Macdonald, L. Health and foreign policy: Influences of migration and population mobility. Bull. World Health Organ. 2007, 85, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author and Year | Study Population | Sample Size (N) | Length of Stay in Canada (N) | Location | Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lum, I.D et al. (2016) | Ethnicity/origin: Belarus, China, Colombia, Iraq | 13: Male = 4, Female = 9 | Average 9 years | Ontario | Method: qualitative study Design: cross-sectional, semistructured interview Analysis: thematic analysis |

| Woodgate, R. L. et al. (2017) | Ethnicity/origin: 15 African countries | 108: Male = 70, Female = 38 | ≤6 years | Manitoba | Method: qualitative study Design: cross-sectional, open-ended interview Analysis: thematic analysis |

| Gulati, S. et al. (2012) | Ethnicity/origin: Chinese and South Asian | 50: Male = 13, Female = 37 | <4 years (7) 4–10 years (18) >10 years (25) | Canada | Method: Grounded theory Design: cross-sectional, semistructured interview Analysis: thematic analysis theory building |

| Amin, M. et al. (2012) | Ethnicity/origin: Ethiopian, Eritrean, and Somali | 48 Mothers of 3-years children | <5 years | Edmonton, Alberta | Method: qualitative study Design: cross-sectional, focus group discussion Analysis: thematic analysis health behavior theory |

| Calvasina, P. et al. (2016) | Ethnicity/origin: Brazilian | 101: Male = 27, Female = 74 | <5 years (80) >5 years (21) | Toronto, Ontario | Method: quantitative study Design: cross-sectional, self-administered survey Analysis: logistic regression |

| Cloos, P. et al. (2020) | Ethnicity/origin: Asia, Caribbean, Europe, Latin America, Middle East, Africa, and United States | 806: Male = 283, Female = 495 | <5 years (593) ≥5 years (178) | Montreal | Method: quantitative study Design: cross-sectional, questionnaire Analysis: multivariable logistic regression |

| Harrington, D. et al. (2013) | Ethnicity/origin: Immigrants and Born in Canada | 7060: Male = 3460, Female = 3600 | <10 years (1765) >10 years (5295) | Urban/Rural, Ontario | Method: quantitative study Design: cross-sectional, CCHS: telephone survey Analysis: multivariable logistic regression |

| Hulme, J et al. (2016) | Ethnicity/origin: Chinese and South-Asian (Bangali) | 23 Women | <5 years (7) >5 years (10) N/A (6) | Ontario | Method: qualitative study Design: cross-sectional, semistructured interview and focus group discussion Analysis: thematic analysis |

| Mumtaz, Z et al. (2014) | Ethnicity/origin: Asia, Africa, Europe, America | 140 women | Since 1996 | Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba | Method: quantitative study Design: cross-sectional, structure CATI Analysis: Pearson’s chi square test |

| Corscadden, L et al. (2018) | Ethnicity/origin: Immigrants | 18 people | NA | Canada | Method: quantitative study Design: cross-sectional, survey Analysis: logistic regression |

| Marshall E. G et al. (2010) | Ethnicity/origin: Chinese and Punjabi | 78: Male = 46, Female = 32 | <10 years (52) ≥10 years (26) | British Columbia | Method: qualitative study Design: cross-sectional, focus group discussion Analysis: thematic analysis |

| Ou, C.H.K et al. (2017) | Ethnicity/origin: Chinese | 8 Adult | 5–19 years (average 14 years) | Vancouver | Method: qualitative study Design: cross-sectional, structured interview: in-person and telephone Analysis: deductive content/themes analysis |

| George, P et al. (2014) | Ethnicity/origin: Muslim- Arab and South Asian countries | 22 women | 1–25 years | Ottawa | Method: qualitative study Design: cross-sectional, focus group discussion Analysis: thematic analysis |

| Higginbottom, G. M. et al. (2016) | Ethnicity/origin: Sudan, Philippines, China, Columbia, Tajikistan, India, Mauritania, Pakistan Eritrea | 34 women | NA | Rural/Urban, Alberta | Method: qualitative study Design: ethnographic research, semistructured interview Analysis: Roper and Shapira’s framework analysis |

| Lee, T.Y. et al. (2014) | Ethnicity/origin: Chinese (China, Hong Kong, Taiwan) | 15 women | <10 years | Canada | Method: qualitative-descriptive phenomenology Design: cross-sectional, semistructured interview Analysis: thematic analysis |

| Dastjerdi, M. et al. (2012) | Ethnicity/origin: Iranian community) | 17: Male = 6, Female = 11 | 2–15 years | Western Canada | Method: qualitative study Design: constructive grounded theory interview Analysis: thematic analysis theory building |

| Ngwakongnwi E. et al. (2012) | Ethnicity/origin: Francophone Immigrant | 26: Male = 11, Female = 5 | <10 years (16) >10 years (6) | Calgary, Alberta | Method: qualitative descriptive study Design: cross-sectional, semistructured telephone interview Analysis: thematic analysis theory building |

| Wang, L. et al. (2015) | Ethnicity/origin: Korean community | 351: Male = 173, Female = 178 | <5 years (17) 5–9 years (6) 10–19 years (14) >20 years (16) | Toronto | Method: Mixed methods Design: cross-sectional, CCHS survey and focus group discussion Analysis: Z-test, thematic analysis |

| Pollock, Grace et al. (2012) | Ethnicity/origin: Middle Eastern, African, Latin American, South Asian, eastern European, Caribbean | 26: Male = 7, Female = 19 | NA | Ontario | Method: qualitative study Design: cross-sectional, semistructured interview Analysis: thematic analysis |

| Author and Year | Study Focus | Patient Experiences/Barriers Mentioned |

|---|---|---|

| Lum, I.D et al. (2016) | Examining the experiences of immigrants living in a small urban center—primary healthcare system | Factors impacting access to primary care: 1. Lack of social contacts 2. Lack of universal healthcare coverage during their initial arrival 3. Language as a barrier 4. Treatment preferences 5. Geographic distance to primary care |

| Woodgate, R. L. et al. (2017) | Examining the experiences of access to PHC by African immigrant and refugee families | Major barriers to primary care services: 1. Expectation not quite met: accessibility, promptness of services, availability, affordability, and acceptable of services 2. Facing a new life in unfamiliar environment 3. Linguistic and cultural differences, lack of social support/network |

| Gulati, S. et al. (2012) | Exploring the role of communication and language in the healthcare experiences of immigrant parents of children with cancer living | Barriers to care: 1. Language/communication challenges influenced parents’ role in caring child 2. Health literacy—difficulty to understand medical terminology, inadequate interpretation services, occasionally missed resources, reported limited availability of linguistically and culturally appropriate information 3. Lack of social integration in the healthcare process and competence |

| Amin, M. et al. (2012) | Identifying psychosocial barriers to providing and obtaining preventive dental care for preschool children among African recent immigrants | Barriers were associated with: 1. Home-based prevention: health beliefs, knowledge, oral health approach, skills 2. Perceived role of caregivers and dentists 3. Role of parental knowledge in access to professional care and preventive services, attitudes toward dentists and services, English skills, and external constraints concerned dental insurance, social support, time, and transportation. |

| Calvasina, P. et al. (2016) | Investigating the association between oral (dental) health literacy (OHL) and participation in oral healthcare among Brazilian immigrants | 83.1% had adequate OHL; low OHL and access of care was associated with: 1. Not visiting a dentist or having a dentist as the primary source of information 2. Not participating in shared dental treatment decision making: language barrier 3. Low average annual income of household |

| Cloos, P. et al. (2020) | Examining the social determinants of self-perceived health of migrants with precarious status (MPS) | Almost half 44.8% perceived their health as negative. Barriers were reported as: 1. Having no diploma/primary/secondary education 2. Unmet needs due to low family income 3. No financial backup or assistance resources 4. Perception of racism 5. Feeling of psychological distress 6. Unmet healthcare needs; having one or more health issue in past 12 months |

| Harrington, D. et al. (2013) | Barriers in accessing to specialty care for all populations including subgroup of immigrant populations | 1. Newcomers (69.2%) and longer-term immigrants (72.1%) were more likely to report difficulties with wait times compared to Canadian-born (64.3%). 2. 14.2% newcomers experienced difficulties: transportation, cost, or language 3. Newcomers reported due to personal or family responsibilities they experience difficulties (23.3%) compared to Canadian-born (9.8%) and longer-term immigrant respondents (10.5%) |

| Hulme, J et al. (2016) | Exploring perception of Chinese and South-Asian immigrants regarding breast and cervical cancer screening | Major themes reported were: 1. Risk perception and concepts of preventative health and screening—"painful or traumatic encounters" 2. Health system engagement and the embedded experience with screening:Female provider vital 3. Fear of cancer and procedural pain 4. Self-efficacy, obligation, willingness to be screened 5. Newcomer barriers and competing priorities: new healthcare system, language, transportation, childcare, work, limited social network, and cultural |

| Mumtaz, Z et al. (2014) | Exploring newcomer women’s experiences in Canada regarding pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum care | 1. Financial—newcomers were more likely to be university graduates but had lower incomes than Canadian-born women. 2. Information—no differences found-newcomer’s ability to access acceptable prenatal care, but fewer received information: emotional/physical changes during pregnancy |

| Corscadden, L et al. (2018) | Assessing the factors associated with multiple barriers in accessing and care-seeking process in different healthcare systems | Barriers to accessing primary care clinic: 1. After-hours access very difficult 2. Over five days to get appointment; no timely response to call 3. Cost for medicines, clinic visit 4. Care not coordinated 5. GP did not spend enough time/unclear explanation. |

| Marshall E. G et al. (2010) | Conceptualizing unmet healthcare needs and primary healthcare experiences among Chinese- and Punjabi-speaking immigrants | Experiences and barriers to accessing care: 1. Costly dental and speech therapy (trade-off between service and paying out-of-pocket) 2. Lack of choice in the gender of a provider 3. Lack of primary care provider accepting new patient, speaking patient’s language 4. Lack of health system literacy: limited knowledge; not enough information provided by service providers; less responsive healthcare system 5. Language is a noticeably big barrier to understanding medical terminology, information about health |

| Ou, C.H.K et al. (2017) | Examining the health beliefs, health behaviors, primary care access, and perceived unmet healthcare needs of Chinese young adults | Barriers experienced: 1. Inaccessibility to primary care provider and preventive services. 2. Influence of cultural factors such as strong family ties, filial piety, and practice of Traditional Chinese Medicine on healthcare behaviors and access 3. Long wait for specialist 4. Low literacy about healthcare system (dental) |

| George, P et al. (2014) | Understanding health behaviors of the minority population and identifying barriers to accessing reproductive health | Health seeking behavior barriers identified: 1. Gender of physician for reproductive health 2. Preference of family physician from same ethnic and cultural background 3. Language barrier while communicating with care providers |

| Higginbottom, G. M. et al. (2016) | Understanding immigrant women’s experiences in maternity healthcare and devising potential intervention that might improve the experiences and outcomes | Barriers reported in accessing care: 1. Communication difficulties 2. Lack of Information 3. Lack of social support 4. Cultural belief 5. Inadequate healthcare services 6. Cost of medicine/services |

| Lee, T.Y. et al. (2014) | Exploring immigrant Chinese women’s experiences in accessing maternity care, the utilization of maternity health services, and the obstacles they perceived | Patient preference/experiences: 1. Preference of having linguistically and culturally competent healthcare providers 2. Dealing with different healthcare system—felt complex 3. Having information in different language felt convenient, but insufficient 4. Satisfied with Canadian Healthcare System, but long wait time long transportation (distance) 5. Felt lacking alternative support |

| Dastjerdi, M. et al. (2012) | Exploring and understanding the experience of Iranian immigrants who accessed Canadian healthcare services | Barrier facing in accessing healthcare: 1. Language barriers (missed appointment, could not trust healthcare providers and services) 2. Financial barriers 3. Cultural difference: felt discrimination and unvalued: help was not sought and waiting to be asked 4. Felt marginalized, humiliation—interpretation services process 5. New healthcare system: felt overwhelmed, exhausted, and burned out 6. Hard to understand health information—available only in English |

| Ngwakongnwi E. et al. (2012) | Examining healthcare access experiences of immigrants and nonimmigrants, French speakers in a mainly English-speaking province of Canada | Barrier reported in accessing care: 1. Difficulty finding family doctor 2. Language barrier: difficulty to explain, emotional distress prior to visit doctor, feelings disconnected, delay in seeking care 3. Complexity of language interpreter service 4. Preference of having culturally and linguistically competent providers 5. Knowledge of healthcare system, transportation barriers, and cost of drugs for recent immigrant |

| Wang, L. et al. (2015) | Capturing health status and experiences in accessing local and transnational healthcare among South Korean immigrants | Preference and barriers expressed: 1. Social cultural and language barriers: preference of Korean-speaking physician, not understanding medical terms, hard to express medical symptoms 2. Lack of social network and support felt left behind. 3. Geographic barriers: long distance to see doctor 4. Economic barrier: lack of extended health insurance for drugs, dental, vision, and other essential care, using traditional Chinese medicine 5. Seeking transnational healthcare: accessing healthcare from Korea physically/online/telephone 6. Waiting time: nearly half participants expressed long wait for diagnosis and treatment 7. Overall, favorable healthcare system, but expected to have comprehensive annual health checkup |

| Pollock, Grace et al. (2012) | Capturing the perceptions of discrimination from a service user perspective in five small and medium-sized Ontario cities | Participant-reported experiences: 1. Refusal to provide healthcare as an immigrant 2. Staff acting as a gatekeeper: refused patient from the reception 3. Communication/language barriers and culturally insensitivity 4. Perceived discrimination: compromised the quality of care, doctor’s inattentiveness about health concerns |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bajgain, B.B.; Bajgain, K.T.; Badal, S.; Aghajafari, F.; Jackson, J.; Santana, M.-J. Patient-Reported Experiences in Accessing Primary Healthcare among Immigrant Population in Canada: A Rapid Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8724. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238724

Bajgain BB, Bajgain KT, Badal S, Aghajafari F, Jackson J, Santana M-J. Patient-Reported Experiences in Accessing Primary Healthcare among Immigrant Population in Canada: A Rapid Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(23):8724. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238724

Chicago/Turabian StyleBajgain, Bishnu Bahadur, Kalpana Thapa Bajgain, Sujan Badal, Fariba Aghajafari, Jeanette Jackson, and Maria-Jose Santana. 2020. "Patient-Reported Experiences in Accessing Primary Healthcare among Immigrant Population in Canada: A Rapid Literature Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 23: 8724. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238724

APA StyleBajgain, B. B., Bajgain, K. T., Badal, S., Aghajafari, F., Jackson, J., & Santana, M.-J. (2020). Patient-Reported Experiences in Accessing Primary Healthcare among Immigrant Population in Canada: A Rapid Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(23), 8724. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238724