Development and Validation of a Sexual-Outlook Questionnaire (SOQ) for Adult Populations in the Republic of Korea

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Participants

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Patient and Public Involvement

2.5. Questionnaire Development

2.6. Data Collection

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics

3.2. Possible Items and Content Validity

3.3. Construct Validity

3.3.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

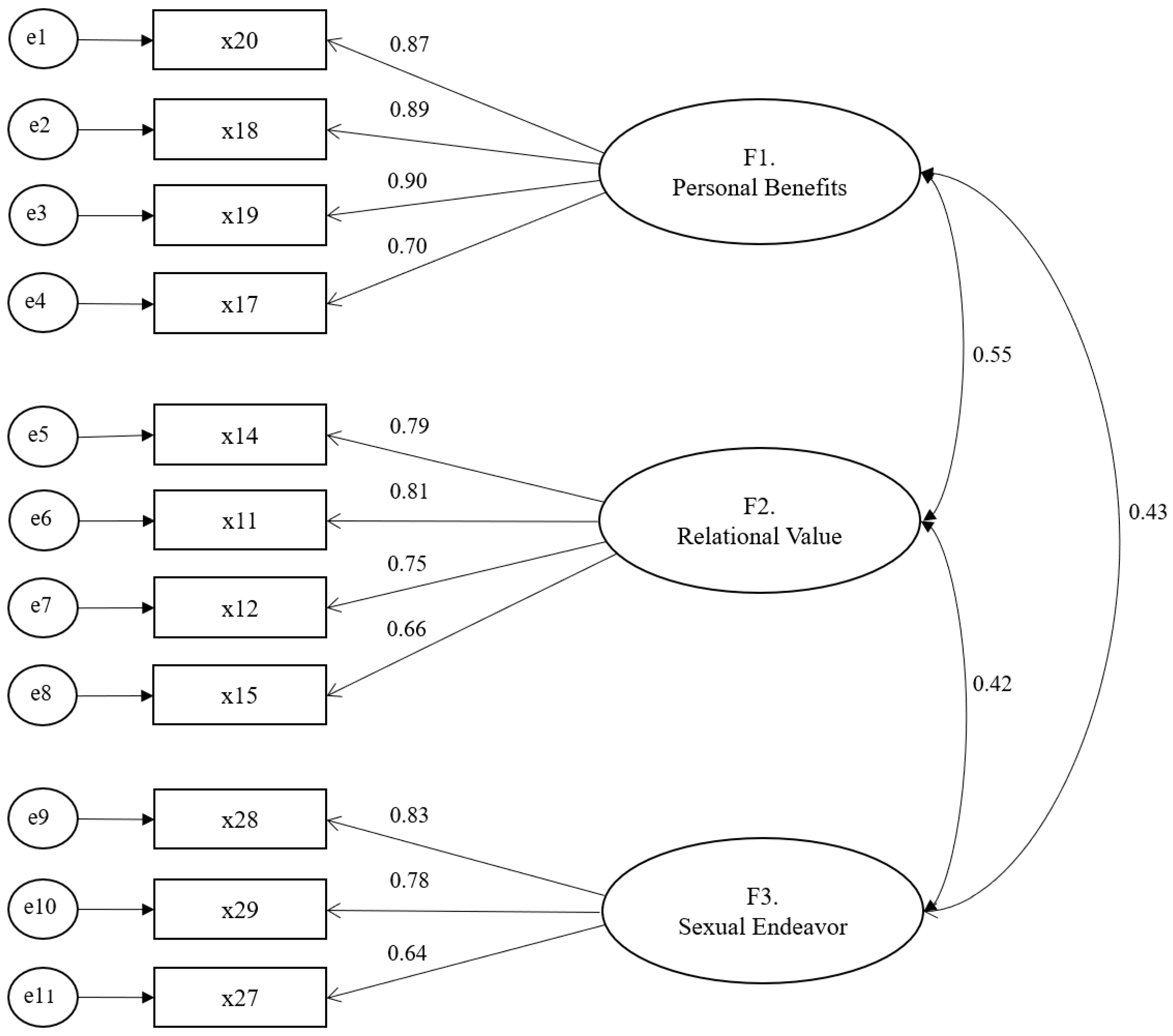

3.3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.3.3. Reliability

3.4. Convergent and Predictive Validity

3.5. The Finalized Model from the Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.6. Score Differences between Disabled and Non-Disabled

3.7. Difference between Persons with and without Sexual Problems

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, S.; Kim, W.; Yoon, G.; Chae, K. Human Sexuality; Koonja Publishing: Seoul, Korea, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cuskelly, M.; Gilmore, L. Attitudes to Sexuality Questionnaire (Individuals with an Intellectual Disability): Scale development and community norms. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2007, 32, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudson, W.W.; Murphy, G.J.; Nurius, P.S. A short-form scale to measure liberal vs. conservative orientations toward human sexual expression. J. Sex Res. 1983, 19, 258–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrick, C.; Hendrick, S.S.; Reich, D.A. The brief sexual attitudes scale. J. Sex Res. 2006, 43, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.; Shin, S.; Cha, H. Development and Validation of a Sexual Attitude Scale for Elderly Korean People. J. Korean Gerontol. Nurs. 2014, 16, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasier, A.; Gülmezoglu, A.M.; Schmid, G.P.; Moreno, C.G.; Van Look, P.F. Sexual and reproductive health: A matter of life and death. Lancet 2006, 368, 1595–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inelmen, E.M.; Sergi, G.; Girardi, A.; Coin, A.; Toffanello, E.D.; Cardin, F.; Manzato, E. The importance of sexual health in the elderly: Breaking down barriers and taboos. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2012, 24, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Degauquier, C.; Absil, A.-S.; Psalti, I.; Meuris, S.; Jurysta, F. Impact of aging on sexuality. Rev. Med. Brux. 2012, 33, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Derogatis, L.R. Psychological Assessment of Psychosexual Functioning. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 1980, 3, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. The Differences of Sexual Attitudes and Sexual Behaviors Based on the Married Women’s Type of Orgasm and Orgasmic Disorder. Korean J. Woman Psychol. 2012, 17, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C.B. A scale for the assessment of attitudes and knowledge regarding sexuality in the aged. Arch. Sex. Behav. 1982, 11, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S.; Ullman, J.B. Using Multivariate Statistics; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.P. Concept and Understanding of Structural Equation Model; Hannarae: Seoul, Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ware, J.E.; Snow, K.K.; Kosinski, M.; Gandek, B.; The Health Institute, New England Medical Center. SF-36 Health Manual and Interpretation Guide; The Health Institute, New England Medical Center: Boston, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ayalon, L.; Gewirtz-Meydan, A.; Levkovich, I. Older Adults’ Coping Strategies with Changes in Sexual Functioning: Results from Qualitative Research. J. Sex. Med. 2019, 16, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdolmanafi, A.; Nobre, P.; Winter, S.; Tilley, P.M.; Jahromi, R.G. Culture and Sexuality: Cognitive–Emotional Determinants of Sexual Dissatisfaction Among Iranian and New Zealand Women. J. Sex. Med. 2018, 15, 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, K.E.; Magnan, M.A. Nursing Attitudes and Beliefs toward Human Sexuality: Collaborative research promoting evidence-based practice. Clin. Nurse Spec. 2005, 19, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.W.; Jung, Y.Y.; Park, S. Evaluation and Application of the Korean Version of the Sexuality Attitudes and Beliefs Survey for Nurses. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2012, 42, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemcić, N.; Novak, S.; Marić, L.; Novosel, I.; Kronja, O.; Hren, D.; Marušić, A.; Marušić, M. Development and validation of questionnaire measuring attitudes towards sexual health among university students. Croat. Med. J. 2005, 46, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sung, K.M.; Lee, S.Y. Development of sexual values scale for college students. J. Korean Soc. Sch. Health 2018, 31, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Lee, B.S.; Han, S.J. Sexual activity and factors influencing the sexual adjustment in men with spinal cord injury. J. Korean Clin. Nurs. Res. 2014, 20, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedde, H.; Van De Wiel, H.; Schultz, W.W.; Vanwesenbeeck, I.; Bender, J. Sexual Health Problems and Associated Help-Seeking Behavior of People With Physical Disabilities and Chronic Diseases. J. Sex Marital. Ther. 2012, 38, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | n (%) | M ± SD 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 48.26 ± 11.09 | |

| 30–39 | 78 (23.4) | |

| 40–49 | 105 (31.4) | |

| 50–49 | 95 (28.4) | |

| >60 | 56 (16.8) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 174 (52.1) | |

| Female | 160 (47.9) | |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 267 (79.9) | |

| Divorce | 33 (9.9) | |

| Other | 34 (10.2) | |

| Religion | ||

| Yes | 206 (61.7) | |

| No | 128 (38.3) | |

| Education level | ||

| ≤Middle school | 36 (10.8) | |

| High school | 74 (22.1) | |

| College or Bachelor | 166 (49.7) | |

| Master or Doctor | 58 (17.4) | |

| Work status | ||

| Employed | 232 (69.5) | |

| Unemployed | 102 (30.5) | |

| Residence | ||

| Seoul | 210 (62.9) | |

| Gyeonggi-do | 124 (37.1) | |

| Chronic disease | ||

| Yes | 92 (27.5) | |

| No | 242 (72.5) | |

| Disability | ||

| Yes | 121 (36.2) | |

| No | 213 (63.8) | |

| Sexual problems | ||

| Yes | 115 (34.4) | |

| No | 219 (65.6) | |

| Importance of sexual life (0 to 10, higher scores mean greater importance) | 6.09 ± 2.32 |

| Items | Factor Loading | Communality | CVI | ITC (r) | Eigenvalues | VE (%) | CV (%) | Cronbach’s α | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | |||||||||

| Factor 1 (Benefit) | 3.135 | 28.503 | 28.503 | 0.902 | |||||||

| x20 | Sexual life makes me feel alive. | 0.871 | 0.238 | 0.105 | 0.826 | 0.893 | 0.899 | ||||

| x18 | Sexual life gives me peace of mind. | 0.870 | 0.238 | 0.137 | 0.832 | 0.857 | 0.911 | ||||

| x19 | Sexual life increases my self-esteem. | 0.813 | 0.355 | 0.179 | 0.819 | 0.893 | 0.891 | ||||

| x17 | Sexual life increases the motivation to live. | 0.812 | 0.010 | 0.206 | 0.702 | 0.821 | 0.827 | ||||

| Factor 2 (Value) | 2.809 | 25.538 | 54.042 | 0.839 | |||||||

| x14 | Sexual life improves the relationship with the spouse (partner). | 0.131 | 0.846 | 0.103 | 0.743 | 1 | 0.632 | ||||

| x11 | Sexual life is an expression of love. | 0.262 | 0.785 | 0.143 | 0.705 | 0.964 | 0.701 | ||||

| x12 | Sexual life is a means of communication. | 0.267 | 0.767 | 0.059 | 0.663 | 1 | 0.652 | ||||

| x15 | I can discuss a sexual matter with my spouse (partner) | 0.055 | 0.757 | 0.192 | 0.613 | 0.964 | 0.586 | ||||

| Factor 3 (Assertiveness) | 2.138 | 19.435 | 73.477 | 0.787 | |||||||

| x28 | If I have a sex problem, I will consult with an expert. | 0.078 | 0.204 | 0.864 | 0.794 | 1 | 0.677 | ||||

| x29 | If I am given an opportunity, I will receive sex education. | 0.115 | 0.183 | 0.833 | 0.740 | 0.929 | 0.667 | ||||

| x27 | If needed in my sexual life, I will use a sex aid. | 0.347 | 0.026 | 0.723 | 0.644 | 1 | 0.593 | ||||

| Total | 0.867 | ||||||||||

| KMO (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin) = 0.865, Total variance explained = 73.477, x2 = 1996.341 (p < 0.001) | |||||||||||

| Item | B | SE | β | CR | Construct Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 (Personal Benefits) | 0.92 | 0.73 | ||||

| x20 | 1.11 | 0.08 | 0.87 | 14.86 * | ||

| x18 | 1.12 | 0.07 | 0.89 | 15.12 * | ||

| x19 | 1.12 | 0.07 | 0.90 | 15.21 * | ||

| x17 | 1.00 | 0.70 | ||||

| Factor 2 (Relational Value) | 0.92 | 0.74 | ||||

| x14 | 1.33 | 0.11 | 0.79 | 11.81 * | ||

| x11 | 1.35 | 0.11 | 0.81 | 11.95 * | ||

| x12 | 1.31 | 0.12 | 0.75 | 11.35 * | ||

| x15 | 1.00 | 0.66 | ||||

| Factor 3 (Sexual Endeavor) | 0.78 | 0.55 | ||||

| x28 | 1.19 | 0.11 | 0.83 | 10.84 * | ||

| x29 | 1.13 | 0.11 | 0.78 | 10.78 * | ||

| x27 | 1.00 | 0.64 | ||||

| Model Fitness: χ2 = 113.417 *, χ2/df = 2.766, RMR = 0.047, RMSEA = 0.073, GFI = 0.941, CFI = 0.963, TLI = 0.950 | ||||||

| Factor 1 & 2 (0.55), Factor 1 & 3 (0.43), Factor 2 & 3 (0.42) | ||||||

| Factor n | Item No. | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | SOQ_Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1: Personal Benefits | x20 | 0.899 | 0.428 | 0.339 | 0.752 |

| x18 | 0.911 | 0.429 | 0.354 | 0.766 | |

| x19 | 0.891 | 0.525 | 0.406 | 0.811 | |

| x17 | 0.827 | 0.249 | 0.355 | 0.659 | |

| Factor_1 | 1 | 0.456 | 0.412 | 0.843 | |

| Factor 2: Relational Value | x14 | 0.339 | 0.857 | 0.266 | 0.593 |

| x11 | 0.439 | 0.844 | 0.319 | 0.661 | |

| x12 | 0.422 | 0.820 | 0.257 | 0.616 | |

| x15 | 0.285 | 0.763 | 0.295 | 0.541 | |

| Factor_2 | 0.456 | 1 | 0.347 | 0.735 | |

| Factor 3: Sexual Endeavor | x28 | 0.290 | 0.330 | 0.863 | 0.621 |

| x29 | 0.311 | 0.312 | 0.844 | 0.616 | |

| x27 | 0.430 | 0.237 | 0.809 | 0.636 | |

| Factor_3 | 0.412 | 0.347 | 1 | 0.745 | |

| Importance of sexual life | 0.526 * | 0.374 * | 0.310 * | 0.531 * |

| Factor n | Disability | t (p) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| M ± SD 1 | |||

| Factor 1 | 13.65 ± 3.21 | 12.64 ± 3.20 | 2.763 (0.006) |

| Factor 2 | 15.74 ± 2.43 | 16.14 ± 2.19 | −1.530 (0.127) |

| Factor 3 | 10.08 ± 2.64 | 9.12 ± 2.51 | 3.313 (0.001) |

| Total | 39.48 ± 6.80 | 37.91 ± 6.03 | 2.180 (0.030) |

| Factor n | Sexual Problems | t (p) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| M ± SD 1 | |||

| Factor 1 | 13.24 ± 3.37 | 12.89 ± 3.17 | 0.958 (0.339) |

| Factor 2 | 15.66 ± 2.47 | 16.17 ± 2.17 | −1.957 (0.051) |

| Factor 3 | 9.28 ± 2.76 | 9.57 ± 2.51 | −0.962 (0.337) |

| Total | 38.18 ± 6.87 | 38.64 ± 6.07 | −0.621 (0.535) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, S.H.; Lee, H.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Lee, B.S. Development and Validation of a Sexual-Outlook Questionnaire (SOQ) for Adult Populations in the Republic of Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8681. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228681

Kim SH, Lee HY, Lee SY, Lee BS. Development and Validation of a Sexual-Outlook Questionnaire (SOQ) for Adult Populations in the Republic of Korea. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(22):8681. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228681

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Sun Houng, Hyang Yuol Lee, Seung Young Lee, and Bum Suk Lee. 2020. "Development and Validation of a Sexual-Outlook Questionnaire (SOQ) for Adult Populations in the Republic of Korea" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 22: 8681. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228681

APA StyleKim, S. H., Lee, H. Y., Lee, S. Y., & Lee, B. S. (2020). Development and Validation of a Sexual-Outlook Questionnaire (SOQ) for Adult Populations in the Republic of Korea. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 8681. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228681