‘Sex Is Not Just about Ovaries.’ Youth Participatory Research on Sexuality Education in The Netherlands

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Recruitment of the Peer Researchers

2.3. Capacity Building and Coaching of Peer Researchers

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Ethics

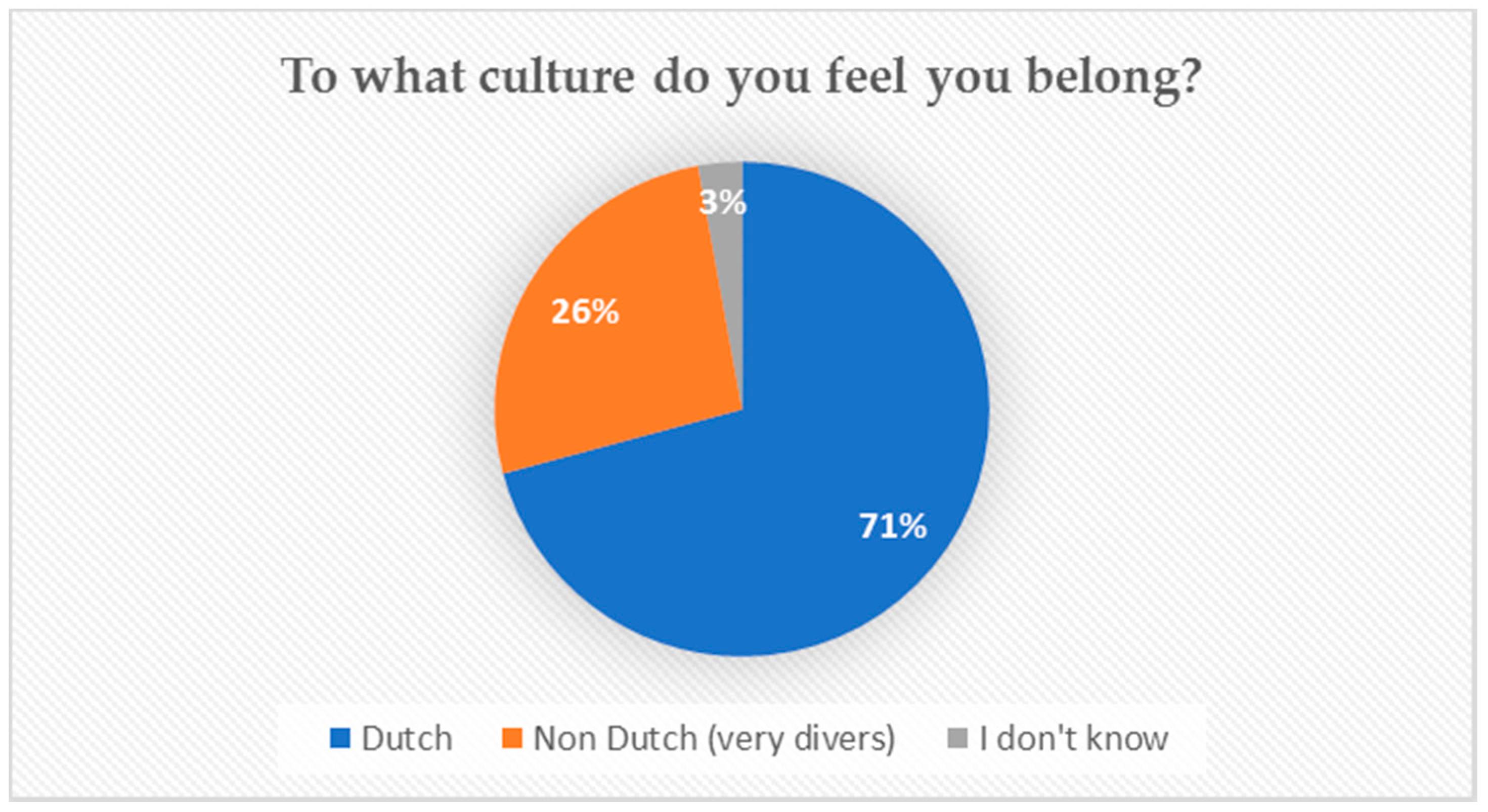

3. Results

3.1. Young People Express a Strong Need for More Sexuality Education during Their Whole School Career

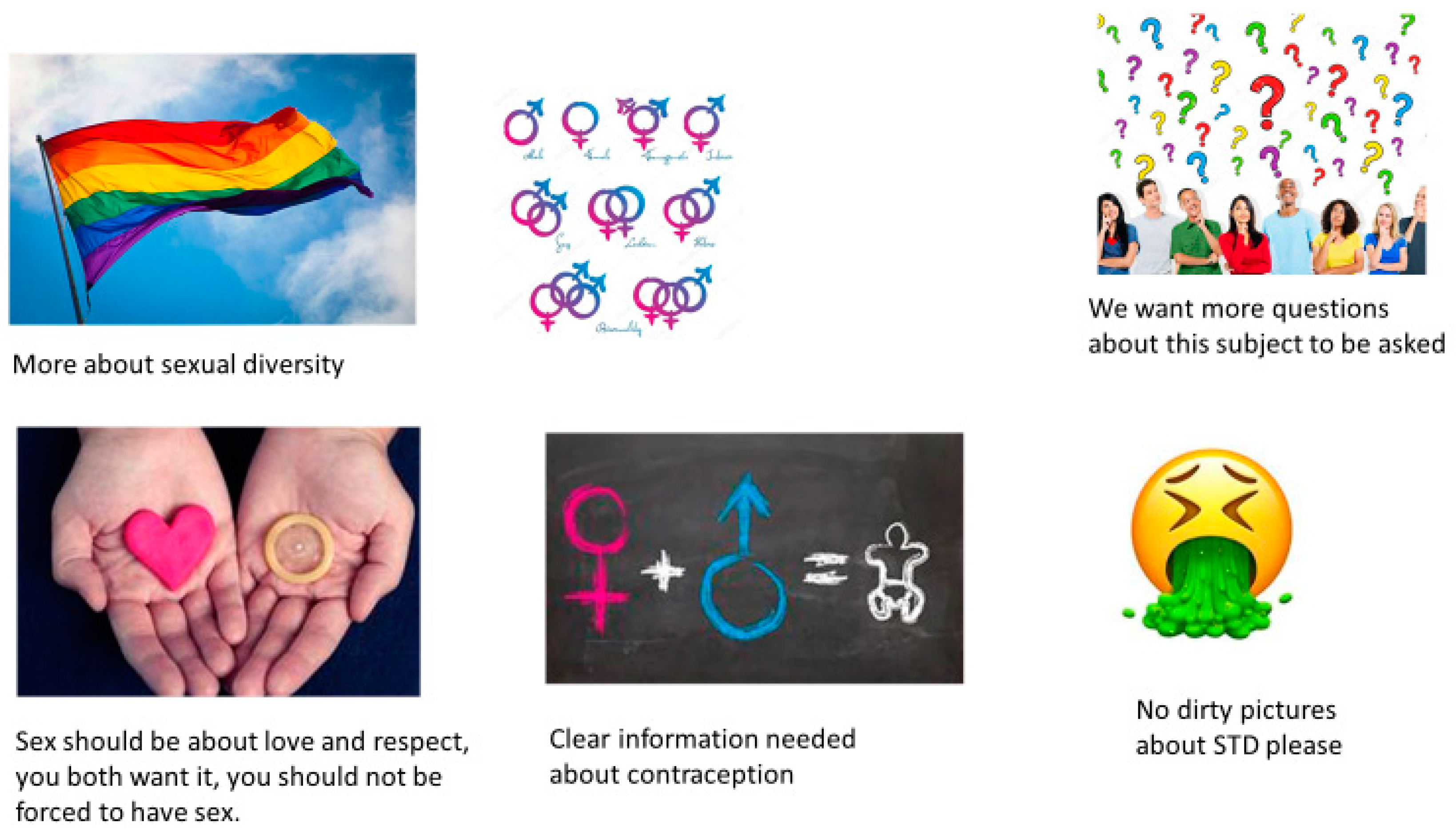

3.2. Sexuality Education Should Cover More Issues

3.3. Sexuality Education Requires a Safe Atmosphere and a Self-Confident and Sensitive Teacher

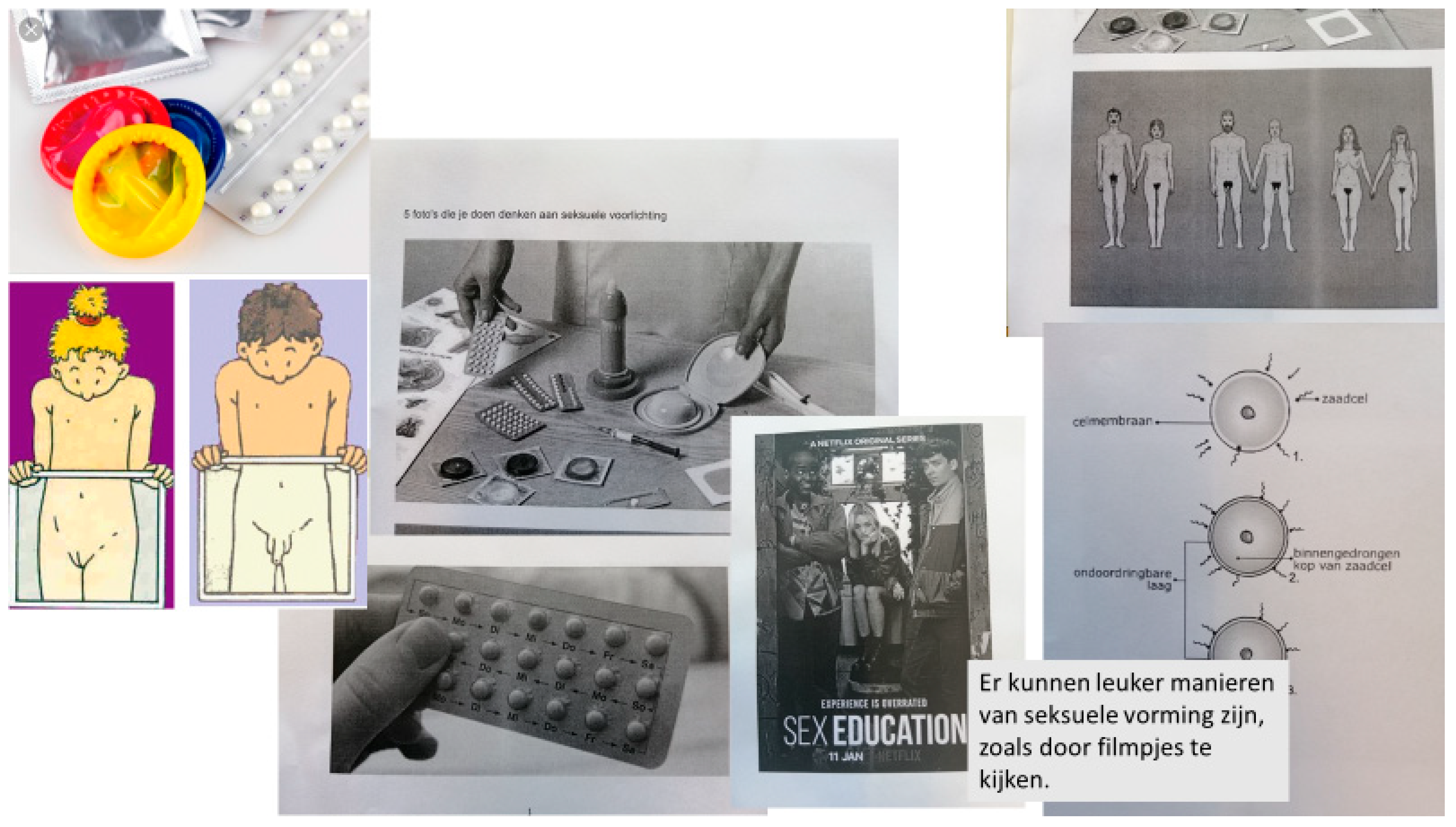

3.4. Young People Want Diverse Teaching Methods

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lewis, J.; Knijn, T. The politics of sex education policy in England and Wales and the Netherlands since the 1980s. J. Soc. Policy 2002, 31, 669–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalet, A. Raging hormones, regulated love: Adolescent sexuality and the constitution of the modern individual in the United States and The Netherlands. Body Soc. 2000, 6, 75–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graaf, H.; de Nikkelen, S.; van den Borne, M.; Twisk, D.; Meijer, S. Seks Onder je 25e. Seksuele Gezondheid van Jongeren in Nederland Anno 2017; [Sex under 25. Sexual Health of Youth in the Netherlands in 2017]; Eburon: Delft, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Inspectie Onderwijs [Dutch Inspectorate of Education]. Omgaan met Seksualiteit en Seksuele Diversiteit. Een Beschrijving van het Onderwijsaanbod van Scholen [Dealing with Sexuality and Sexual Diversity. A Description of the School Curricula of Dutch Schools]; Ministry of Education, Culture and Science: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2016.

- Bonjour, M.; Van der Vlugt, I. Comprehensive Sexuality Education. Knowledge File; Rutgers: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Expert Group on Sexuality Education. Sexuality education: What is it? Sex Educ. 2016, 16, 427–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutte, L.; Meertens, R.M.; Mevissen, F.E.F.; Schaalma, H.; Meijer, S.; Kok, G. Long Live Love. The Implementation of a School-Based Sex-Education Program in the Netherlands. Health Educ. Res. 2014, 29, 583–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohlrichs, Y.; van der Vlugt, I.; van de Walle, R. Seksuele Vorming in Onderwijsmethoden voor het Voortgezet Onderwijs Kritisch onder de Loep! [Sexuality Education in Course Material for Secondary Schools—A Critical Look]; Rutgers: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Aggleton, P.; Campbell, C. Working with young people—Towards an agenda for sexual health. Sex. Relatsh. Ther. 2000, 15, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, L. ‘They Think You Shouldn’t be Having Sex Anyway’: Young People’s Suggestions for Improving Sexuality Education Content. Sexualities 2008, 11, 573–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, L. ‘It’s not “who” they are it’s “what they are like”’: Re-conceptualising sexuality education’s ‘best educator’ debate. Sex Educ. 2009, 9, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Higgins, S.; Gabhainn, S.N. Youth participation in setting the agenda: Learning outcomes for sex education in Ireland. Sex Educ. 2010, 10, 387–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.A.; Fonseca, L.; Araújo, H.C. Sex education and the views of young people on gender and sexuality in Portuguese schools. Educ. Soc. Cult. 2012, 35, 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Gowen, L.K.; Winges-Yanez, N. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, and Questioning Youths’ Perspectives of Inclusive School-Based Sexuality Education. J. Sex Res. 2014, 51, 788–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, C.; Shiman, L.J.; Dowling, E.A.; Tantay, L.; Masdea, J.; Pierre, J.; Lomax, D.; Bedell, J. LGBTQ+ students of colour and their experiences and needs in sexual health education: ‘You belong here just as everybody else’. Sex Educ. 2020, 20, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Lisdonk, J.; Nencel, L.; Keuzenkamp, S. Labeling Same-Sex Sexuality in a Tolerant Society that Values Normality: The Dutch Case. J. Homosex. 2017, 65, 1892–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meerhoff, S. Hardnekkig Hetero: ‘Seksuele diversiteit’ in de praktijk van het middelbaar schoolonderwijs. [The Heteronorm Prevails: Teaching Sexual Diversity in the Netherlands]. Relig. Samenlev. 2016, 11, 156–174. [Google Scholar]

- Bay-Cheng, L.Y. The Trouble of Teen Sex: The construction of adolescent sexuality through school-based sexuality education. Sex Educ. 2003, 3, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.H. Reading Sociology into Scholarship on School-Based Sex Education: Interaction and Culture. Sociol. Compass 2012, 6, 526–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, L. “Now Why Do You Want to Know About That?”: Heteronormativity, Sexism, and Racism in the Sexual (Mis)Education of Latina Youth. Gend. Soc. 2009, 23, 520–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, S.; Roberts, T.; Plocha, A. Girls of Color, Sexuality, and Sex Education; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Weekes, D. Get Your Freak on: How Black Girls Sexualise Identity. Sex Educ. 2002, 2, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitten, A.; Sethna, C. What’s missing? Antiracist sex education! Sex Educ. 2014, 14, 414–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, M.L. Pleasure/Desire, Sexularism and Sexuality Education. Sex Educ. 2012, 12, 469–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodsaz, R. Probing the Politics of Comprehensive Sexuality Education: ‘Universality’ Versus ‘Cultural Sensitivity’: A Dutch-Bangladeshi Collaboration on Adolescent Sexuality Education. Sex Educ. 2018, 18, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjakdar, F. Can difference make a difference? A critical theory discussion of religion in sexuality education. Discourse Stud. Cult. Polit. Educ. 2018, 39, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coll, L.; O’Sullivan, M.; Enright, E. ‘The Trouble with Normal’: (re)Imagining sexuality education with young people. Sex Educ. 2018, 18, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebbekx, W. What else can sex education do? Logics and effects in classroom practices. Sexualities 2018, 22, 1325–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringrose, J. Postfeminist Education? Girls and the Sexual Politics of Schooling; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, L. ‘Say everything’: Exploring young people’s suggestions for improving sexuality education. Sex Educ. 2005, 5, 389–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pound, P.; Langford, R.; Campbell, R. What do young people think about their school-based sex and relationship education? A qualitative synthesis of young people’s views and experiences. BMJ Open 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.; Harrison, L.; Ollis, D.; Flentje, J.; Arnold, P.; Bartholomaeus, C. ‘It Is not All about Sex’: Young People’s Views about Sexuality and Relationships Education; Report of Stage 1 of the Engaging Young People in Sexuality Education Research Project; University of South Australia: Adelaide, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, J.; Shen, X.; Hesketh, T. Sexual Knowledge, Attitudes and Behaviours among Undergraduate Students in China—Implications for Sex Education. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Switched On: Sexuality Education in the Digital Space; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Devotta, K.; Woodhall-Melnik, J.; Pedersen, C.; Wendaferew, A.; Aratangy, T.; Guilcher, S.J.T.; Hamilton-Wright, S.; Ferentzy, P.; Hwang, S.W.; Matheson, F.I. Enriching qualitative research by engaging peer interviewers: A case study. Qual. Res. 2016, 16, 661–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lushey, C.J.; Munro, E.R. Participatory peer research methodology: An effective method for obtaining young people’s perspectives on transitions from care to adulthood? Qual. Soc. Work 2015, 14, 522–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, G. Reflections on co-investigation through peer research with young people and older people in sub-Saharan Africa. Qual. Res. 2016, 16, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, E.; le May, A.; Kébé, F.; Flink, I.; van Reeuwijk, M. Experiences of being, and working with, young people with disabilities as peer researchers in Senegal: The impact on data quality, analysis, and well-being. Qual. Soc. Work 2018, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, R.A.; Casey, M.A. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Researchers, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jongeling, S.; Bakker, M.; van Zorge, R. Photovoice. Facilitator’s Guide; Rutgers: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Catalani, C.; Minkler, M. Photovoice: A review of the literature in health and public health. Health Educ. Behav. 2010, 37, 424–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutgers and IPPF. EXPLORE Toolkit for Involving Young People as Researchers in Sexual and Reproductive Health Programmes. 2013. Available online: http://www.rutgers.international/our-products/tools/explore (accessed on 9 April 2018).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FGB (Faculty of Behavioural Sciences). Code of Ethics for Research in the Social and Behavioural Sciences Involving Human Participants; As accepted by the Deans of Social Sciences in the Netherlands, January 2016; FGB, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; Available online: https://fgb.vu.nl/en/Images/ethiek-reglement-adhlandelijk-nov-2016_tcm264-810069.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2018).

- Bailey, S.; Boddy, K.; Briscoe, S.; Morris, C. Involving disabled children and young people as partners in research: A systematic review. Child Carehealth Dev. 2014, 41, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cense, M. Navigating a bumpy road. Developing sexuality education that supports young people’s sexual agency. Sex Educ. 2019, 19, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naezer, M. From risky behaviour to sexy adventures: Reconceptualising young people’s online sexual activities. Cult. Health Sex. 2017, 20, 715–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geijsel, F.; Ledoux, G.; Reumerman, R.; ten Dam, G. Citizenship in Young People’s Daily Lives: Differences in Citizenship Competences of Adolescents in the Netherlands. J. Youth Stud. 2012, 15, 711–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, S.; Strange, V.; Oakley, A.; The RIPPLE Study Team. What do young people want from sex education? The results of a needs assessment from a peer-led sex education programme. Cult. Health Sex. 2004, 6, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, K.; Ellis, S.; Abbott, R. “We Don’t Get into All That”: An Analysis of How Teachers Uphold Heteronormative Sex and Relationship Education. J. Homosex. 2015, 62, 1638–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo, C. LGBTQ Youth and Education: Policies and Practices; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Applebaum, B. Social justice, democratic education and the silencing of words that wound. J. Moral Educ. 2003, 32, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education, an Evidence-Informed Approach, Revised Edition; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vanwesenbeeck, I.; Cense, M.; van Reeuwijk, M.; Westeneng, J. Understanding sexual agency. Implications for sexual health programming. Sex. Reprod. Health Matters. under review.

- Vanwesenbeeck, I. Comprehensive sexuality education. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Global Public Health; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naezer, M.; Rommes, E.; Jansen, W. Empowerment through sex education? Rethinking paradoxical policies. Sex Educ. 2017, 17, 712–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Aim | Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Semi-structured Interviews | Contributes to research question 2, 3, and 4 by exploring:

|

|

| Focus Group Discussions | Contributes to research question 1, 2, 3, and 4 by exploring more in-depth:

|

|

| Photovoice Sessions | Contributes to research question 1 by exploring in a visual way: What good sexuality education looks like, in the eyes of pupils | What does good sexuality education look like? |

| School | Girls (n = 13) | Boys (n = 4) | Other (n = 0) | Total (n = 17) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 3 | ||

| 2 | 2 | 2 | ||

| 3 | 2 | 2 | ||

| 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | |

| 5 | 2 | 2 | 4 | |

| 6 | 2 | 2 |

| School | Location | Education Type | Religious Affiliation | Composition School Population | Sex Education Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Boxtel (rural) | HAVO/VWO (middle and higher level) | Roman Catholic | Mainly white | Biology textbooks |

| 2 | Rotterdam (urban) | Gymnasium (Higher level) | Christian | Mainly white | Biology textbooks |

| 3 | Hengelo (rural) | HAVO/VWO (middle and higher level) | Public | Mainly white | Biology textbooks |

| 4 | Almere (urban) | VMBO/HAVO/VWO (all levels) | Christian | Multicultural | Biology textbooks |

| 5 | Althorn (rural) | HAVO/VWO (middle and higher level) | Roman Catholic | Multicultural | Biology textbooks, Gender and Sexuality Alliance |

| 6 | Breda (urban) | VMBO/HAVO/VWO (all levels) | Public | Multicultural | Biology textbooks; method Long Live Love |

| Participants. | Girls (n = 156) | Boys (n = 144) | Other (n = 0) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Educational Level | Educational Level | ||||

| Practice-Based | Theory-Based | Practice-Based | Theory-Based | Total | |

| Peer researchers | 0 | 13 | 0 | 4 | 17 |

| Participants interviews | 26 | 71 | 32 | 67 | 196 |

| Participants FGD | 3 | 23 | 8 | 8 | 42 |

| Photovoice participants | 8 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 45 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cense, M.; Grauw, S.d.; Vermeulen, M. ‘Sex Is Not Just about Ovaries.’ Youth Participatory Research on Sexuality Education in The Netherlands. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8587. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228587

Cense M, Grauw Sd, Vermeulen M. ‘Sex Is Not Just about Ovaries.’ Youth Participatory Research on Sexuality Education in The Netherlands. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(22):8587. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228587

Chicago/Turabian StyleCense, Marianne, Steven de Grauw, and Manouk Vermeulen. 2020. "‘Sex Is Not Just about Ovaries.’ Youth Participatory Research on Sexuality Education in The Netherlands" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 22: 8587. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228587

APA StyleCense, M., Grauw, S. d., & Vermeulen, M. (2020). ‘Sex Is Not Just about Ovaries.’ Youth Participatory Research on Sexuality Education in The Netherlands. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 8587. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228587