1. Introduction

In 2016, car accidents were the eighth leading cause of death, causing 1.35 million fatalities worldwide, with a rate of 18.2% per 100,000 inhabitants [

1]. It has been widely reported that the driver having consumed alcohol increases both the risk of car accidents and the risk that they will cause severe injury or death [

2,

3,

4]. Globally, 21.8% of all deaths from vehicular accidents are related to alcohol, resulting in approximately 306,002 deaths [

5].

Many countries have implemented drunk driving laws to reduce alcohol-related car crash deaths, and Chile is no exception. In the last decade, there have been two significant legal changes: the Zero Tolerance Law (ZTL) in 2012 and Emilia’s Law (EML) in 2014. While the ZTL decreased the grams of alcohol in the blood legally permissible for driving and increased the driver’s license suspension, EML added at least one year of actual imprisonment for drunk driving responsible for severe injury or fatal car crashes. EML did not change the limits on the amount of alcohol present in the driver [

6].

While most of the empirical evidence has focused on lowering blood alcohol limits for driving on car accidents and deaths [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13], less is known about the effects of increasing penalties, such as actual imprisonment for drunk driving, on the abovementioned outcomes [

14,

15,

16,

17]. As noted by Weinrath and Gartrell [

18], “we actually know little about the deterrence effect of imprisonment.” More important, most of the empirical evidence on the effects of imprisonment on traffic fatalities finds nonsignificant effects.

In this paper, we assess the short- and medium-run effects of Chile’s ZTL and EML on vehicle accidents, injuries, and deaths with a special focus on the deterrence effect of including prison sentences for drunk driving. As argued by Hansen [

19], increasing the marginal punishment when the driver’s blood alcohol content (BAC) level is higher may cause the driver to internalize the external costs of driving while intoxicated. This is especially true for drivers with very high alcohol levels for whom the external costs are higher, since such cases are more likely to lead to severe injuries or deaths. However, Bouffard, Niebuhr, and Exum [

20] show that there is not always a deterrence effect of higher sentences for this type of crime. Other authors have expressed contrasting views about the effectiveness of prison sentences in the past. While some short-term effects were found by Nichols and Ross [

15] and Kenkel [

16], none were found by Ross and Klette [

17] or Ross, McCleary & Lafree [

14].

We have access to a rich dataset on car accidents and their causes to study the direct effects of each law on alcohol-related crashes. Our data include detailed information on injuries and deaths associated with each accident. We also have access to blood alcohol tests to assess the effects of these laws on drinking and driving.

The empirical approach follows Otero and Rau [

13]. We implement negative binomial regressions to assess the effects of these laws on alcohol-related accidents, injuries, and deaths. Generalized linear models and censored quantile regressions are estimated to evaluate the BAC changes associated with the two legal changes.

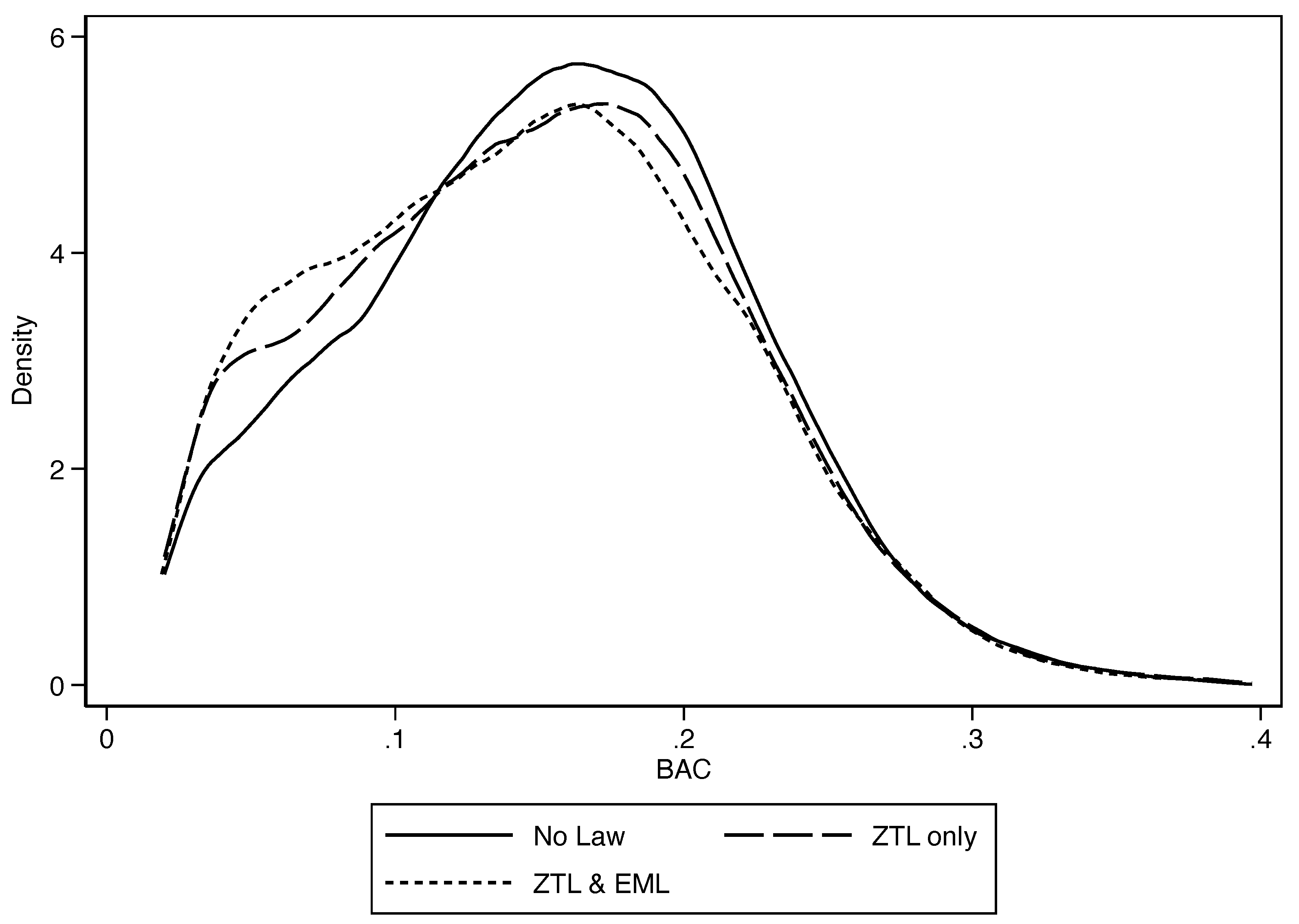

We found statistically significant reductions in alcohol-related accidents and injuries associated with the ZTL, but they were short-lived. On the other hand, EML is associated with a permanent reduction in alcohol-related accidents and injuries. Neither of the laws affects traffic fatalities. For the ZTL, there are associated reductions in male drivers’ alcohol intake only; for EML, reductions are present for males and females. However, the effects do not reach higher quantiles of the BAC distribution.

2. Institutional Background

In Chile, car crashes are the second leading cause of death of young people between 15 and 25 years old and the first among children under 15 years old [

21]. The number of road deaths was nearly 1950 in 2018, with a rate of 10.5 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants and an estimated cost of traffic crashes of approximately US

$ 6 billion for the state [

22]. Moreover, for the 2009–2017 period, approximately 30,000 drivers were apprehended every year for driving under the influence of alcohol (DUI) or while intoxicated, causing nearly 5140 traffic accidents, 5070 injured, and 165 deaths [

23].

To decrease the social losses caused by DUI and drunk driving, Chile’s senate approved two legal changes regarding drunk driving in the last decade. On 15 March 2012, Law 20, 580 (the ZTL) was enacted, lowering the legal driving BAC level and increasing the license revocation period for DUI and drunk driving. The permitted BAC was reduced from 0.05 to 0.03 g/dL, and DUI was set between 0.03 and 0.079 BAC (instead of the former 0.05–0.099 BAC range). The starting threshold for drunk driving was reduced from 0.1 to 0.08 BAC. For reference purposes, other countries that lowered the legal BAC in recent decades are Russia, Sweden, and Norway, which decreased it from 0.05 to 0.02 g/dL, and Poland and Japan, which did so from 0.05 to 0.03 g/dL [

8,

24].

There are two characteristics of the penalty structure in Chile that deserve to be noted. One is the distinction between DUI (between 0.03 and 0.079 BAC) and drunk driving (above 0.08 BAC), and the second is that the license suspension period depends on the type of injuries caused by the car crash. See Otero and Rau [

13] for a complete description of the ZTL and its effects.

On 16 September 2014, Law 20,770 (EML) was enacted. This law resulted from a citizen initiative when on 21 January 2013, a nine-month-old minor, Emilia Silva, died after a driver with 0.19 g/dL of alcohol struck her parents’ car, which produced considerable media and social commotion. The EML modified the traffic law concerning the crime of DUI and driving while intoxicated. It punishes DUI and drunk drivers who cause severe injuries or death with at least one year of actual imprisonment. Additionally, it established as a crime to fleeing from the scene of an accident and refusing to submit to a blood alcohol test or breathalyzer [

6].

Thus, while the ZTL reduces the legal driving BAC level and increased the license revocation period for DUI and drunk driving, EML increased the penalties, including at least one year of actual imprisonment, for DUI and drunk drivers who cause severe injuries or deaths. Since EML only changed the penalty structure, we are able to place particular focus on the deterrence effect of including prison sentences, absent the influence of other changes that could be confound with the effect of increasing penalties.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that in Chile, individuals must be 18 years or older to drive alone. There is a special permit for teens at 17 that allows them to drive when accompanied by an adult driver. Additionally, buying alcohol is legal for those 18 years of age or older.

5. Discussion

Our results reveal a significant short-term reduction in alcohol-related accidents and injuries for both laws. For the ZTL, the effects are short-lived, as found previously by other authors for different BAC laws [

13,

41,

42]. A common explanation for this lack of impact in the long run is the limited enforcement of the law after its enactment. However, for EML, the magnitude of the results does not decrease with time. Hence, in the Chilean context, the inclusion of an actual prison sentence may have a sustained effect on alcohol-related accidents and injuries.

While we find significant results for alcohol-related accidents and injuries after the enactment of both laws, we do not find a significant effect of the ZTL or EML on deaths. As noted by Otero and Rau [

13], such a result may be due to a lack of statistical power given the small number of deaths. However, this lack of effect is consistent with previous findings in the international literature [

43,

44,

45]. As discussed by Grant [

44] and Otero and Rau [

13], one explanation is simply that these types of laws affect drivers involved in non-fatal accidents. Given that drunk drivers cause the vast majority of deaths in alcohol-related accidents, our BAC results provide evidence along these lines.

According to the Carabineros de Chile data, between 2012 and 2017, 79% of deaths in alcohol-related accidents were due to drunk driving (i.e., 0.08 BAC and above) and the rest to DUI (0.03–0.079 BAC). Interestingly, when analyzing the effects of both laws on BAC, our results show a significant impact up to the 90th quantile. Hence, heavy drinkers who drive (above the 90th quantile of the BAC distribution) seem to not change their alcohol consumption, in contrast to drivers who drink less.

Importantly, the ZTL and EML seem to affect the blood alcohol content of drivers differently. First, the ZTL shows stronger effects than EML; the coefficients are larger in magnitude and affect higher quantiles of the BAC distribution. Second, while the ZTL affects male drivers only, EML affects both males and females. The result of BAC laws affecting only males has been previously found in Europe by Albalate [

34] and in the U.S. by Eisenberg [

46]. However, our result of increasing the penalties for DUI and drunk driving on BAC is new. An actual jail sentence affects male and female drivers equally.

Certainly, the deterrence effect of any law may be influenced by its enforcement and severity. The Chilean case offers an interesting opportunity to compare two policies with a similar enforcement level and different harshness in their punishments. While the ZTL considers lengthened license suspension periods, the EML prescribes actual prison sentences.

Our results are consistent with previous findings in the literature. In particular, many authors find that stiffening the penalties for drunk driving, including actual jail time, has no long-term effects on alcohol-related fatalities and other outcomes for various reasons [

14,

15,

16]. Some authors argue that drunk driving laws should focus on increasing the probability of detection for law violators rather than increasing the severity of the penalty [

15]. Other authors state that penalties, including prison sentences, are not severe enough [

16]. Finally, there might be other factors affecting alcohol-related traffic fatalities, such as high taxes on alcohol, marketing restrictions, and inexpensive transportation alternatives [

17].

This paper provides evidence on the effects of introducing actual imprisonment for drunk drivers responsible for severe injuries or fatal crashes. More importantly, the length of the jail sentence under EML of at least one year can be considered harsh relative to other countries’ punishments. Nevertheless, we found no effect on alcohol-related traffic fatalities. One limitation of our study is that we have a post-intervention period of EML of four years only, and the impact of this type of intervention may take longer. More research is needed to assess the effects of drunk driving laws in the long run and fully understand how they work. This might shed light on how they could deter heavy drinkers from driving.