‘As Long as It Comes off as a Cigarette Ad, Not a Civil Rights Message’: Gender, Inequality and the Commercial Determinants of Health

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Corporate Practices and Their Implications for Gender Inequalities

2.1. Gender in Marketing—What Women Want?

Frankly, we weren’t sure, with our theme “You’ve come a long way, Baby”—that we could run this advertising in Ebony, but why not? As long as it still comes off as a cigarette ad, not a civil rights message.(Hal Weinstein, 1969 [42].)

The rise of women consumers offers a great opportunity for us to grow in the future. That is a target segment we need to keep in mind and ensure that our brands get more bilingual and speak to both sets of audiences, not just be male-centric.(Bhavesh Somaya, Diageo India [56].)

2.2. Gender in CSR—Empowering Women?

2.3. Summary: Corporate Practices and Gender Inequalities

3. Corporate Strategies, Structural Power and Gender Inequalities

3.1. Industry Consolidation and Expansion Into Emerging Markets

3.2. Companies View Women’s Increasing Economic Independence as an Opportunity to Expand Their Markets

3.3. Companies Actively Resist Market Regulation

3.4. Companies Use Tactics in Low- and Middle-Income Settings That Are Restricted in High-Income Countries

3.5. The Impact of Industry Strategies on Women’s Health and Gender Inequalities

3.6. Summary: Corporate Strategies and Gender Inequalities

4. Conclusions

Limitations of the Current Evidence Base, and Priorities for Future Research

Images

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prehn, E.C.; Galbraith, J.K. The Age of Uncertainty. J. Econ. Educ. 1977, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kickbusch, I.; Allen, L.; Franz, C. The commercial determinants of health. Lancet Glob. Health 2016, 4, e895–e896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maani, N.; Collin, J.; Friel, S.; Gilmore, A.B.; McCambridge, J.; Robertson, L.; Petticrew, M.P. Bringing the commercial determinants of health out of the shadows: A review of how the commercial determinants are represented in conceptual frameworks. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 30, 660–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.; Freudenberg, N. Addressing the commercial determinants of health begins with clearer definition and measurement. Glob. Health Promot. 2020, 27, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freudenberg, N. The manufacture of lifestyle: The role of corporations in unhealthy living. J. Public Health Policy 2012, 33, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moodie, R.; Stuckler, D.; Monteiro, C.; Sheron, N.; Neal, B.; Thamarangsi, T.; Lincoln, P.; Casswell, S. Profits and pandemics: Prevention of harmful effects of tobacco, alcohol, and ultra-processed food and drink industries. Lancet 2013, 381, 670–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, M.; Stuckler, D. Revisiting the Corporate and Commercial Determinants of Health. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, 1167–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants of Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Collin, J.; Hill, S. Industrial epidemics and inequalities: The commercial sector as a structural driver of inequalities in non-communicable diseases. In Health Inequalities: Critical Perspectives; Smith, K., Hill, S., Bambra, C., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; Volume 2–16, pp. 177–191. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. WHO Director-General addresses Health Promotion Conference, 10 June 2013. In Opening Address at 8th Global Conference on Health Promotion in Helsinki8th Global Conference on Health Promotion in Helsinki; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; Available online: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/2013/health_promotion_20130610/en/ (accessed on 12 June 2020).

- Östlin, P.; George, A.; Sen, G. Gender, health, and equity: The intersections. In Challenging Inequities in Health: From Ethics to Action; Evan, T., Whitehead, M., Diderichsen, F., Bhuiya, A., Wirth, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001; pp. 174–189. [Google Scholar]

- Acker, J. Gender, Capitalism and Globalization. Crit. Sociol. 2004, 30, 17–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keleher, H.; Franklin, L. Changing gendered norms about women and girls at the level of household and community: A review of the evidence. Glob. Public Health 2008, 3, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, R. Gender, health and theory: Conceptualizing the issue, in local and world perspective. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 74, 1675–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, S.; Buse, K. Gender and global health: Evidence, policy, and inconvenient truths. Lancet 2013, 381, 1783–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtenay, W.H. Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: A theory of gender and health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2000, 50, 1385–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicker, D.; Nguyen, G.; Abate, D.; Abate, K.H.; Abay, S.M.; Abbafati, C.; Abbasi, N.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdela, J.; et al. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality and life expectancy, 1950–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1684–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, S.I.; Abajobir, A.A.; Abate, K.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdulkader, R.S.; Abdulle, A.M.; Abebo, T.A.; Abera, S.F.; et al. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 333 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2017, 390, 1260–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettany, S.; Dobscha, S.; O’Malley, L.; Prothero, A. Moving beyond binary opposition: Exploring the tapestry of gender in consumer research and marketing. Mark. Theory 2010, 10, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulucanlar, S.; Fooks, G.J.; Gilmore, A.B. The Policy Dystopia Model: An Interpretive Analysis of Tobacco Industry Political Activity. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1002125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, V.R. Selling the Sex That Sells: Mapping the Evolution of Gender Advertising Research Across Three Decades. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 1997, 20, 71–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, T. Sex in advertising research: A review of content, effects, and functions of sexual information in consumer advertising. Annu. Rev. Sex Res. 2002, 13, 241–273. [Google Scholar]

- Conley, T.D.; Ramsey, L.R. Killing Us Softly? Investigating Portrayals of Women and Men in Contemporary Magazine Advertisements. Psychol. Women Q. 2011, 35, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilbourne, J. Killing Us Softly 4: Advertising’s Image of Women (Film); Media Education Foundation: Northampton, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Amos, A. From social taboo to “torch of freedom”: The marketing of cigarettes to women. Tob. Control 2000, 9, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Törrönen, J.; Rolando, S. Women’s changing responsibilities and pleasures as consumers: An analysis of alcohol-related advertisements in Finnish, Italian, and Swedish women’s magazines from the 1960s to the 2000s. J. Consum. Cult. 2016, 17, 794–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beccaria, F.; Rolando, S.; Törrönen, J.; Scavarda, A. From housekeeper to status-oriented consumer and hyper-sexual imagery: Images of alcohol targeted to Italian women from the 1960s to the 2000s. Fem. Media Stud. 2017, 18, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C.; Oliffe, J.L.; Bottorff, J.L. From the Physician to the Marlboro Man. Men Masc. 2012, 15, 526–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, G.; Kappel, R. Gender, Alcohol, and the Media: The Portrayal of Men and Women in Alcohol Commercials. Sociol. Q. 2018, 59, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, N.J.; Nichter, M. The marketing of tobacco to women: Global perspectives. In Women and the Tobacco Epidemic: Challenges for the 21st Century; Samet, J.M., Yoon, S.-Y., Eds.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001; pp. 105–136. [Google Scholar]

- Wenner, L.A. Brewing Consumption: Sports Dirt, Mythic Masculinity, and the Ethos of Beer Commercials. In Sport, Beer, and Gender: Promotional Culture and the Contemporary Social Life; Wenner, L.A., Jackson, S.J., Eds.; Peter Lang Publishing Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Starr, M.E. The Marlboro Man: Cigarette Smoking and Masculinity in America. J. Popul. Cult. 1984, 17, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupka, L.R.; Vener, A.M. Gender Differences in Drug (Prescription, Non-Prescription, Alcohol and Tobacco) Advertising: Trends and Implications. J. Drug Issues 1992, 22, 339–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, A.M. Recruiting women smokers: The engineering of consent. J. Am. Med Women’s Assoc. 1996, 51, 63–66. [Google Scholar]

- Toll, B.A. The Virginia Slims identity crisis: An inside look at tobacco industry marketing to women. Tob. Control 2005, 14, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, C.M.; Wayne, G.F.; Connolly, G.N. Designing cigarettes for women: New findings from the tobacco industry documents. Addiction 2005, 100, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euromonitor International. Competitive Strategies in Alcoholic Drinks, November 2018; Euromonitor International: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Euromonitor International. Wine in Eastern Europe, January 2020; Euromonitor International: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Euromonitor International. Looking Back on the White Claw Summer: Inside the American Hard Seltzer Explosion, November 2019; Euromonitor International: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ligget & Myers Tobacco Company. ‘Chesterfield’ cigarette advertisement. In Accessed from Stanford University ‘Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising’ Collection; Durham, N.C., Ed.; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 1927; Available online: http://tobacco.stanford.edu/tobacco_main/images.php?token2=fm_st024.php&token1=fm_img0516.php&theme_file=fm_mt012.php&theme_name=Targeting%20Women&subtheme_name=Mass%20Marketing%20Begins (accessed on 5 July 2020).

- Morris, P. ‘Virginia Slims’ cigarette advertisement. In Stanford University ‘Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising’ Collection; Stanford University: New York, NY, USA, 1989; Available online: http://tobacco.stanford.edu/tobacco_main/images.php?token2=fm_st034.php&token1=fm_img0792.php&theme_file=fm_mt012.php&theme_name=Targeting%20Women&subtheme_name=Women%27s%20Liberation (accessed on 5 July 2020).

- Weinstein, H.; American Association of Advertising Agencies. Papers from the 1969 A.A.A.A. Region Conventions. In How an Agency Builds a Brand—The Virginia Slims Story; Bates No. 1002430048; Accessed from UCSF Legacy Library; University of California San Francisco: San Francisco, CA, USA; Available online: https://www.industrydocuments.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/#id=jmnb0122 (accessed on 12 June 2020).

- Lee, S.; Ling, P.M.; Glantz, S.A. The vector of the tobacco epidemic: Tobacco industry practices in low and middle-income countries. Cancer Causes Control 2012, 23 (Suppl. 1), 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laugesen, M.; Meads, C. Tobacco advertising restrictions, price, income and tobacco consumption in OECD countries, 1960–1986. Br. J. Addict. 1991, 86, 1343–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollay, R.W. Promises, promises: Self-regulation of US cigarette broadcast advertising in the 1960s. Tob. Control 1994, 3, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewhirst, T. Tobacco sponsorship of Formula One and CART auto racing: Tobacco brand exposure and enhanced symbolic imagery through co-sponsors’ third party advertising. Tob. Control 2002, 11, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collin, J.; Muggli, M.; Carlyle, J.; Lee, K.; Hurt, R.D. A race to the death: British American Tobacco and the Chinese Grand Prix. Lancet 2004, 364, 1107–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, A.M.; Pollay, R.W. Deadly targeting of women in promoting cigarettes. J. Am. Med Women’s Assoc. 1996, 51, 67–69. [Google Scholar]

- AB InBev. Annual Report 2019; AB InBev: Leuven, Belgium, 2020; Available online: https://www.ab-inbev.com/investors/annual-reports.html (accessed on 5 July 2020).

- Diageo. Royal Challenge Whisky: Pushing the Boundaries for Women in India; Diageo: London, UK, 2019; Available online: https://www.diageo.com/en/news-and-media/features/royal-challenge-whisky-pushing-the-boundaries-for-women-in-india/ (accessed on 7 July 2020).

- Euromonitor International. Diageo PLC in Spirits (World), September 2019; Euromonitor International: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Corti, B.; Ibrahim, J. Women and alcohol—Trends in Australia. Med. J. Aust. 1990, 152, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, K.M.; Li, G.; Hasin, D.S. Birth Cohort Effects and Gender Differences in Alcohol Epidemiology: A Review and Synthesis. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2011, 35, 2101–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser, M.B.; Jernigan, D.H. Multinational Alcohol Market Development and Public Health: Diageo in India. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 2220–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euromonitor International. Wine in Asia Pacific, November 2019; Euromonitor International: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, S. ‘Sipping Success’: Interview with Bhavesh Somaya, Marketing and Innovation Director, Diageo India; IMPACT Noida; IMPACT: Uttar Pradesh, India, 2014; Available online: https://www.impactonnet.com/amp/cmo-interview/sipping-success-2904.html (accessed on 6 July 2020).

- Fooks, G.; Gilmore, A.; Collin, J.; Holden, C.; Lee, K. The Limits of Corporate Social Responsibility: Techniques of Neutralization, Stakeholder Management and Political CSR. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 112, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fooks, G.J.; Gilmore, A.B. Corporate Philanthropy, Political Influence, and Health Policy. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e80864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babor, T.F.; Robaina, K. Public Health, Academic Medicine, and the Alcohol Industry’s Corporate Social Responsibility Activities. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, S.; Lam, T.H. The illusion of righteousness: Corporate social responsibility practices of the alcohol industry. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, P.A.; Malone, R.E. Creating the ‘desired mindset’: Philip Morris’s efforts to improve its corporate image among women. Women Health 2009, 49, 441–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Robinson, R.G.; Barry, M.; Bloch, M.; Glantz, S.; Jordan, J.; Murray, K.B.; Popper, E.; Sutton, C.; Tarr-Whelan, K.; Themba, M.; et al. Report of the Tobacco Policy Research Group on Marketing and Promotions Targeted at African Americans, Latinos, and Women. Tob. Control 1992, 1 (Suppl. 1), S24–S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, M. Women, Blacks Courted: Big Tobacco Buying New Friendships. Los Angeles Times 1988. Available online: https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1988-05-22-mn-4888-story.html (accessed on 23 August 2020).

- Jones, S.C.; Wyatt, A.; Daube, M. Smokescreens and beer goggles: How alcohol industry CSM protects the industry. Soc. Mark. Q. 2016, 22, 264–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BAT. A Better Tomorrow. In Sustainability Strategy Report 2019; British American Tobacco: London, UK, 2020; Available online: https://www.bat.com/sustainabilityreport (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- IWD. Educating a Global Workforce on What International Women’s Day Stands for International Women’s Day, 2018. Available online: https://www.internationalwomensday.com/Activity/12724/BestPractice-PrivateSector-IWD#Bat-bookmark (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- Foster, L. Why Gender-Targeted Products and Marketing Failed in 2018. 20 November 2018. Just-Drinks. 2018. Available online: https://www.just-drinks.com/analysis/why-gender-targeted-products-and-marketing-failed-in-2018-consumer-trends_id127220.aspx (accessed on 6 July 2020).

- BrewDog. Pink IPA. Ellon: BrewDog. Available online: https://www.brewdog.com/blog/pink-ipa/ (accessed on 7 July 2020).

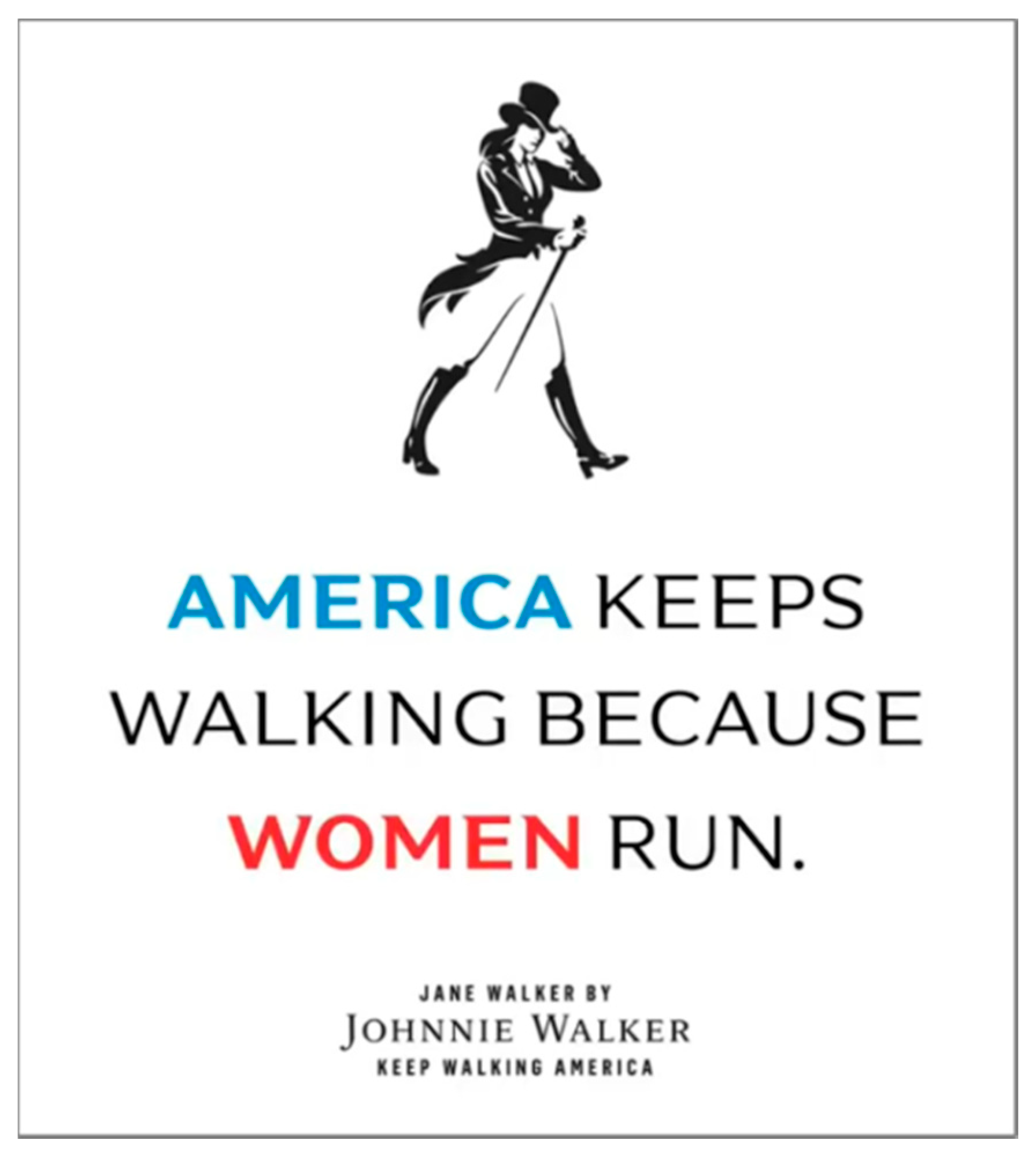

- Paskin, B. Jane Walker Whisky Launches in US. 26 February 2018. Available online: https://scotchwhisky.com/magazine/latest-news/18005/jane-walker-whisky-launches-in-us/ (accessed on 13 July 2020).

- Gunelius, S. The Problem with Johnnie Walker’s Jane Walker Scotch Was Perception; 7 March 2018; Entrepreneur: Irving, CA, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/309990 (accessed on 13 July 2020).

- Johnnie Walker US. Jane Walker by Johnny Walker ‘Keep Walking America’ Promotional Video, Posted 7 November 2018 on Johnnie Walker US Instagram. Available online: https://www.instagram.com/p/Bp40ZM9D0-t/ (accessed on 13 July 2020).

- PMI. Delivering a Smoke-Free Future—Progress Towards a World Without Cigarettes. In Integrated Report 2019; Philip Morris International: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.pmi.com/integrated-report-2019 (accessed on 23 August 2020).

- Diageo. Annual Report 2019; Diageo: London, UK, 2020; Available online: https://www.diageo.com/en/investors/reporting-centre/ (accessed on 7 July 2020).

- CARE International. CARE and Diageo: A Global Value Chain Approach to Promoting Women’s Empowerment; CARE International: London, UK, 2020; Available online: https://www.careinternational.org.uk/get-involved/corporate-partnerships/who-we-work-with/Diageo (accessed on 7 July 2020).

- CARE International. A Win for Women Worldwide: Historic Global Treaty to End Violence and Harassment at Work Agreed Today; 21 June 2019; CARE International: London, UK, 2019; Available online: https://www.careinternational.org.uk/win-women-worldwide-historic-global-treaty-end-violence-and-harassment-work-agreed-today (accessed on 7 July 2020).

- AB InBev. #NoExcuse Campaign Tackles Violence Against Women. 26 July 2018. Available online: https://www.ab-inbev.com/news-media/smart-drinking/noexcuse-campaign-tackles-violence-against-women.html (accessed on 7 July 2020).

- de Villiers, J. How Carling Black Label Reached More Than 45 Million People Worldwide to Fight Violence Against Women. Business Insider South Africa, 7 September 2018. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.co.za/carling-black-label-noexcuse-anti-gender-based-violence-campaign-reach-45-million-people-loerie-award-2018-8 (accessed on 7 July 2020).

- Hur, W.-M.; Kim, H.; Woo, J. How CSR Leads to Corporate Brand Equity: Mediating Mechanisms of Corporate Brand Credibility and Reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 125, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramsky, T.; Watts, C.H.; Garcia-Moreno, C.; Devries, K.; Kiss, L.; Ellsberg, M.; Jansen, H.A.; Heise, L. What factors are associated with recent intimate partner violence? findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carling Black Label South Africa. Image from Orlando Pirates Football Club v Kaizer Chiefs Football Match, FNB Stadium, Johannesburg, 3 March 2018. Posted on Carling Black Label South Africa Facebook Page 7 May 2020. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/CarlingBlackLabelSA/photos/a.193849537299611/2127798380571374 (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- Beneria, L. Globalization, gender and the Davos Man. Fem. Econ. 1999, 5, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polanyi, K. The Great Transformation; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, G.; Östlin, P. Gender inequity in health: Why it exists and how we can change it. Glob. Public Health 2008, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Women. Facts and Figures: Economic Empowerment. Last Updated July 2018. New York, N.Y. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/economic-empowerment/facts-and-figures (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- UNRISD. Research and Policy Brief 9: Why Care Matters for Social Development; United Nations Research Institute for Social Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; Available online: http://www.unrisd.org/80256B3C005BCCF9/(httpAuxPages)/25697FE238192066C12576D4004CFE50/%24file/RPB9e.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2020).

- The Economist. Generation XX: January 2069. Economist 2018, 428, S8–S9. [Google Scholar]

- Farnsworth, K.; Holden, C. The Business-Social Policy Nexus: Corporate Power and Corporate Inputs into Social Policy. J. Soc. Policy 2006, 35, 473–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Liemt, G. The World Tobacco Industry: Trends and Prospects. Working Paper, Sectoral Activities Programme; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Euromonitor International. Alcoholic Drinks—Global Industry Overview, August 2019; Euromonitor International: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan, D.H. The global alcohol industry: An overview. Addiction 2009, 104, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thun, M.; Peto, R.; Boreham, J.; Lopez, A.D. Stages of the cigarette epidemic on entering its second century. Tob. Control 2012, 21, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doku, D. The tobacco industry tactics—A challenge for tobacco control in low and middle income countries. Afr. Health Sci. 2010, 10, 201. [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane, J.; Chen, H.; Conigrave, K.M.; Hao, W. Alcohol use in china. Alcohol Alcohol. 2003, 38, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vendrame, A. When evidence is not enough: A case study on alcohol marketing legislation in Brazil. Addiction 2016, 112 (Suppl. 1), 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, J.; Johnson, E.; Officer, H.; Hill, S. Government support for alcohol industry: Promoting exports, jeopardising global health? BMJ 2014, 348, g3648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saloojee, Y.; Dagli, E. Tobacco industry tactics for resisting public policy on health. Bull. World Health Organ. 2000, 78, 902–910. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer, E.R.; Brenner, J.E.; Houston, T.P. International trade agreements: A threat to tobacco control policy. Tob. Control 2005, 14 (Suppl. 2), ii19–ii25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Curbing the Epidemic: Governments and the Economics of Tobacco Control; Development in Practice series; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Yach, D. Globalisation of tobacco industry influence and new global responses. Tob. Control 2000, 9, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jernigan, D.H.; Babor, T.F. The concentration of the global alcohol industry and its penetration in the African region. Addiction 2015, 110, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Euromonitor International. World Market for Cigarettes, October 2019; Euromonitor International: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, R. Consolidation in the tobacco industry. Tob. Control 1998, 7, 426–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Collin, J.; Hill, S.E.; Smith, K.E. Merging alcohol giants threaten global health. BMJ 2015, 351, h6087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Tobacco Industry Interference with Tobacco Control; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Euromonitor International. Eight Trends in African Innovation, September 2019; Euromonitor International: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Euromonitor International. Cigarettes in Asia Pacific, November 2019; Euromonitor International: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Quaye, A. Presentation to AB InBev’s Investor Seminar, 8 August 2018, Johannesburg, South Africa; AB InBev: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; Available online: https://www.ab-inbev.com/investors/Presentations/presentations-collection/2018/investor-seminar-presentations-7-9-august--2018.html (accessed on 7 July 2020).

- Lopez, A.D.; Collishaw, N.E.; Piha, T. A descriptive model of the cigarette epidemic in developed countries. Tob. Control 1994, 3, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitchman, S.C.; Fong, G.T. Gender empowerment and female-to-male smoking prevalence ratios. Bull. World Health Organ. 2011, 89, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthey, J.; Shield, K.D.; Rylett, M.; Hasan, O.S.M.; Probst, C.; Rehm, J. Global alcohol exposure between 1990 and 2017 and forecasts until 2030: A modelling study. Lancet 2019, 393, 2493–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, L. Selling addictions: Similarities in approaches between Big Tobacco and Big Booze. Australas. Med. J. 2010, 3, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnoya, J. Tobacco industry success in preventing regulation of secondhand smoke in Latin America: The “Latin Project”. Tob. Control 2002, 11, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assunta, M.; Fields, N.; Knight, J.; Chapman, S. “Care and feeding”: The Asian environmental tobacco smoke consultants programme. Tob. Control 2004, 13, ii4–ii12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assunta, M. Industry sponsored youth smoking prevention programme in Malaysia: A case study in duplicity. Tob. Control 2004, 13, ii37–ii42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.; Collin, J.; Gilmore, A.B. “The law was actually drafted by us but the Government is to be congratulated on its wise actions”: British American Tobacco and public policy in Kenya. Tob. Control 2007, 16, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, J.W.; Tye, J.B.; Fischer, P.M. The tobacco industry’s code of advertising in the United States: Myth and reality. Tob. Control 1996, 5, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Barbeau, E.M.; DeJong, W.; Brugge, D.M.; Rand, W.M. Does cigarette print advertising adhere to the Tobacco Institute’s voluntary advertising and promotion code? An assessment. J. Public Health Policy 1998, 19, 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hastings, G.; Brooks, O.; Stead, M.; Angus, K.; Anker, T.; Farrell, T. Failure of self regulation of UK alcohol advertising. BMJ 2010, 340, b5650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, G. “They’ll Drink Bucket Loads of the Stuff”: An Analysis of Internal Alcohol Industry Advertising Documents; Alcohol Education and Research Council: London, UK, 2009; Available online: http://oro.open.ac.uk/22913/ (accessed on 13 July 2020).

- Casswell, S. Current status of alcohol marketing policy-an urgent challenge for global governance. Addiction 2012, 107, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCambridge, J.; Kypri, K.; Miller, P.; Hawkins, B.; Hastings, G. Be aware of D rinkaware. Addiction 2013, 109, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piazza-Gardner, A.; Barry, A.E. A Drink Best Not Served: Conflicts of Interests When the Alcohol Industry Seeks to Inform Public Health Practice and Policy. J. Clin. Res. Bioeth. 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babor, T.F.; Robaina, K.; Jernigan, D. The influence of industry actions on the availability of alcoholic beverages in the African region. Addiction 2015, 110, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angus, K.; Angus, K.; Emslie, C.; Shipton, D.; Bauld, L. Gender differences in the impact of population-level alcohol policy interventions: Evidence synthesis of systematic reviews. Addiction 2016, 111, 1735–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portman Group. DrinkAware ‘Why Let Good Times Go Bad?’ Campaign Poster, 2011; Portman Group: London, UK, 2011; Available online: https://www.thedrinksbusiness.com/2011/08/drinkaware-ramps-up-campaign/ (accessed on 12 July 2020).

- Casswell, S.; Maxwell, A. Regulation of alcohol marketing: A global view. J. Public Health Policy 2005, 26, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boseley, S. Threats, Bullying, Lawsuits: Tobacco Industry’s Dirty War for the African Market; The Guardian: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bilton, B. The Secret bribes of big tobacco. BBC News (Online), 30 November 2015. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-34964603 (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- BBC Panorama. The Secret Bribes of Big Tobacco; Screened on BBC One Television, 30 November 2015; BBC Panorama: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- David, A.; Esson, K.; Perucic, A.-M.; Fitzpatrick, C. Tobacco use: Equity and social determinants. In Equity, Social Determinants and Public Health Programmes; Blas, E., Kurup, A.S., Eds.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; pp. 199–217. [Google Scholar]

- Savell, E.; Gilmore, A.; Sims, M.; Mony, P.K.; Koon, T.; Yusoff, K.; A Lear, S.; Serón, P.; Ismail, N.; Calik, K.B.T.; et al. The environmental profile of a community’s health: A cross-sectional study on tobacco marketing in 16 countries. Bull. World Health Organ. 2015, 93, 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bruijn, A. Monitoring Alcohol Marketing Practices in Africa: Findings from The Gambia, Ghana, Nigeria and Uganda; WHO Regional Office for Africa: Brazzaville, Congo, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, T.; Gordon, R. Critical social marketing: Investigating alcohol marketing in the developing world. J. Soc. Mark. 2012, 2, 138–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, S.; Buse, K. Gender-responsive tobacco control: Evidence and options for policies and programmes. In Secretariat of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.; Carpenter, C.M.; Challa, C.; Lee, S.; Connolly, G.N.; Koh, H.K. The strategic targeting of females by transnational tobacco companies in South Korea following trade liberalisation. Glob. Health 2009, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collin, J.; Arora, M.; Hill, S. Industrial vectors of non-communicable diseases: A case study of the alcohol industry in India. In Global Health Governance and Commercialisation of Public Health in India; Kapilashrami, A., Baru, R.V., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 97–107. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Empower Women—Combating Tobacco Industry Marketing in the WHO European Region; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2010; Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/en/publications/abstracts/empower-women-combating-tobacco-industry-marketing-in-the-who-european-region (accessed on 23 August 2020).

- Kelly, M.P.; Morgan, A.; Bonnefoy, J.; Butt, J.; Bergman, V. The social determinants of health: Developing an evidence base for political action. In Final Report to the World Health Organization Commission on the Social Determinants of Health; Universidad del Desarrollo: Concepción, Chile; National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Beneria, L. Economics as if all people mattered. In Gender, Development and Globalization; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gostin, L.O.; Gostin, K.G. A broader liberty: JS Mill, paternalism, and the public’s health. Public Health 2009, 123, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, G.; Östlin, P.; George, A. Unequal, Unfair, Ineffective and Inefficient. Gender Inequality in Health: Why it Exists and How We Can Change It. Final Report to the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Women and Gender Equity Knowledge Network. 2007. Available online: https://www.who.int/social_determinants/themes/womenandgender/en/ (accessed on 23 August 2020).

- Parkin, K.J. Food is Love: Food Advertising and Gender Roles in Modern America; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadephia, PA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tangcharoensathien, V.; Chandrasiri, O.; Kunpeuk, W.; Markchang, K.; Pangkariya, N. Addressing NCDs: Challenges from industry market promotion and interferences. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2019, 8, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delobelle, P. Big Tobacco, Alcohol, and Food and NCDs in LMICs: An inconvenient truth and call to action: Comment on ‘Addressing NCDs: Challenges from industry market promotion and interferences’. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2019, 8, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, P.J. Gambling, Freedom and Democracy; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rochford, C.; Tenneti, N.; Moodie, R. Reframing the impact of business on health: The interface of corporate, commercial, political and social determinants of health. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4, e001510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliffe, J.L.; Greaves, L. Designing and Conducting Gender, Sex, and Health Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Promundo. 2020. Available online: https://promundoglobal.org/ (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- Euromonitor International. The Impact of Coronavirus on Tobacco, April 2020; Euromonitor International: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, P.J. Moral Jeopardy: Risks of Accepting Money from the Alcohol, Tobacco and Gambling Industries; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- US Surgeon General. Women and Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General; Office on Smoking and Health, CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2001.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hill, S.E.; Friel, S. ‘As Long as It Comes off as a Cigarette Ad, Not a Civil Rights Message’: Gender, Inequality and the Commercial Determinants of Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7902. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17217902

Hill SE, Friel S. ‘As Long as It Comes off as a Cigarette Ad, Not a Civil Rights Message’: Gender, Inequality and the Commercial Determinants of Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(21):7902. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17217902

Chicago/Turabian StyleHill, Sarah E., and Sharon Friel. 2020. "‘As Long as It Comes off as a Cigarette Ad, Not a Civil Rights Message’: Gender, Inequality and the Commercial Determinants of Health" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 21: 7902. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17217902

APA StyleHill, S. E., & Friel, S. (2020). ‘As Long as It Comes off as a Cigarette Ad, Not a Civil Rights Message’: Gender, Inequality and the Commercial Determinants of Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(21), 7902. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17217902