Abstract

The world is facing a number of challenges related to food consumption. These are, on the one hand, health effects and, on the other hand, the environmental impact of food production. Radical changes are needed to achieve a sustainable and healthy food production and consumption. Public and institutional meals play a vital role in promoting health and sustainability, since they are responsible for a significant part of food consumption, as well as their “normative influence” on peoples’ food habits. The aim of this paper is to provide an explorative review of the scientific literature, focusing on European research including both concepts of health and sustainability in studies of public meals. Of >3000 papers, 20 were found to satisfy these criteria and were thus included in the review. The results showed that schools and hospitals are the most dominant arenas where both health and sustainability have been addressed. Three different approaches in combining health and sustainability have been found, these are: “Health as embracing sustainability”, “Sustainability as embracing health” and “Health and sustainability as separate concepts”. However, a clear motivation for addressing both health and sustainability is most often missing.

1. Introduction

The world is facing a number of challenges related to food consumption. On the one hand, health effects related to lifestyle factors such as dietary habits, may lead to non-communicable diseases (NCD) causing the deaths of 41 million people each year, equivalent to 71% of all deaths globally, and also malnutrition with 462 million people being underweight [1,2]. Of the six WHO regions, Europe is the most severely affected by Non-Communicable Disease (NCDs), the four major NCDs—cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, and respiratory diseases—together account for 77% of the burden of disease and almost 86% of premature mortality. Excess bodyweight and intake of energy, saturated fats, trans fats, sugar, and salt, as well as low consumption of vegetables, fruits, and whole grains are considered the leading risk factors [3]. According to malnutrition the demographic situation in Europe with a growing proportion of the population researching ever-increasing ages means increasing prevalence of disease and thereby increasing risk of disease-related malnutrition [4,5]. On the other hand, the environmental impact of food production and distribution is currently responsible for about 25–30% of total greenhouse gas emissions (GHGE) [6] and radical changes are called for to achieve a target of a maximum 2 °C t increase [7,8]. For the EU food and drink are responsible for 20–30% of various environmental impacts derived from private consumption when analysing the life cycle for all goods consumed within EU [9].

Taken together, there is an urgent need to integrate health and environmental aspects both at an individual and a societal level, in order to achieve sustainability in food consumption in accordance with the United Nation’s (UN) sustainability goals (SDGs) [10]. The public/institutional meal plays an important role in striving for this goal [11], not only because it is responsible for a significant part of many people’s food consumption, but also through its normative influence on peoples’ food habits [12]. In Sweden alone, about 3 million public meals are served per day at an estimated cost of 20–25 billon SEK per year. These meals are regulated by a number of laws, such as the Educational Act, Social Services Act and the Public Procurement Act according quality and financing.

In this paper, public meals are defined as meals taking place in institutional settings [11,13,14]. While the sustainability perspective has only recently been introduced as a research subject in the public meal arena, the health perspective is well established [8,15].

The primary aim of this study is, therefore, to provide an explorative review of the scientific literature, focusing on European research including concepts of health and sustainability in studies of public meals.

The specific research questions are:

- -

- In which public meal arenas has the combination of health and sustainability been addressed?

- -

- Which aspects of health and sustainability are primarily put forward?

- -

- How are health and sustainability associated and what are the motives for combining these factors?

2. Background

2.1. Public Meals

Public meals appear in different arenas and in different forms, covering various needs [16]. The areas of focus in Sweden, as well in western society in general, have often been rational efficiency, and health and nutrition [17]. There are no common regulations for how public meals should be designed or financed. However, using the school lunch as an example, many countries have policies to provide nutritionally balanced meals reflecting the general food culture of the country [18,19,20].

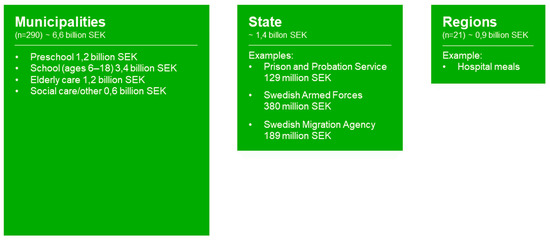

Sweden is one of the leading countries in Europe in terms of the number of public meals served daily and per capita [21]. There is a long history of serving meals free of charge in schools and preschools that started in 1945, and from 1974 free school meals have been served in all Swedish municipalities. The school meal was identified in Sweden early on as an arena for health actions as well as a way to achieve equality in health [22], reaching not only the children but also their parents. These meals have been shown to improve the diet of children [23,24]. In Figure 1, sectors serving public meals in Sweden are shown as an example, illustrating the large variety of public meal settings.

Figure 1.

The figure illustrates different sectors serving meals to users. The sizes of the boxes correspond to the number of meals served in each arena, based on a Swedish context [33,34,35].

Studies have also indicated the role of meals in relation to the health of patients in hospitals [25] and older adults in care homes [26]. These meals constitute one of the most basic parts of medical treatment with the aim of meeting specific nutritional requirements in relation to various medical conditions [27]. In this aspect, patient safety is of the utmost importance with regard to the quality of meals served in the healthcare context. In addition, there are sensory demands; the meals should be appetizing and also constitute an arena for social interaction. Studies have been conducted focusing on food and meals in relation to health among inmates in prison, where the problems of obesity and an unhealthy diet have been raised [28,29]. A study by Wangmo et al. [30] acknowledged the importance of nutritional interventions in prison aimed at improving health. Only a few studies have focused on food and meals in the military service as a public meal arena [31,32].

2.2. Aspects of Health and Sustainability

Both “health” and “sustainability” are complex concepts and their meanings are not always consistent. Already in 1946, the World Health Organization (WHO) created a definition of health that aimed not only at focusing on the physical aspects but also the social and mental aspects of health. Even though this definition has been recurrently criticized for being too utopian, it is still referred to and has been awarded for its holistic approach to health.

“Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” [36].

The role of a healthy diet for the growth of children and the maintenance of health and prevention of disease is indisputable [15,37]. In relation to the social and mental aspects of health, studies have indicated that shared meals, and especially family meals, have positive effects [38,39]. Some studies have also investigated the role of the school meal on mental health, including levels of stress among the students [31], as well as the role of meals for well-being in care homes for elderly persons [40].

In 1983, the United Nations created the World Commission on Environment and Development (Brundtland Commission), which defined sustainable development as:

“Meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [10].

In 1992, the first United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) was held in which Agenda 21 was developed and adopted. When preparing for a follow up meeting, Rio+20 2012, Colombia proposed the idea of the SDGs, which was adopted by the United Nations Department of Public Information, 64th NGO Conference in Bonn, Germany. The resulting 17 SDGs and associated targets were adopted by all United Nations Member States in 2015. Many of the goals included health and the environment aspects.

The EAT-report [8] from 2019 states:

“Without action, the world risks failing to meet the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Paris Agreement, and today’s children will inherit a planet that has been severely degraded and where much of the population will increasingly suffer from malnutrition and preventable disease”.

3. Materials and Methods

An explorative review was conducted where scientific databases were searched for articles discussing the public meal in relation to both health and sustainability. The search string used is reported below and the used databases are given in Table 1. The criteria for selection of papers are given in Table 2.

Table 1.

Databases for search of papers.

Table 2.

Criteria for inclusion of papers.

Search string for identification of relevant literature:

(“Public meal” OR “public meals” OR “Institutional meal” OR “Institutional meals” OR “School meal” OR “School meals” OR “pre-school meal” OR “pre-school meals” OR “School lunch” OR “School lunches” OR “Workplace meal” OR “Workplace meals” OR “Institutional food” OR “Institutional catering” OR “Public restaurant” OR “Public restaurants” OR “Public sector meal” OR “Public sector meals” OR “Public food service” OR “Public food services” OR “School meal system” OR “School meal systems” OR “Public kitchen” OR “Public kitchens” OR “Food service” OR “Food services” OR “institutional fare” OR “Catering service” OR “catering services” OR catering OR Canteen OR Canteens) AND (Sustainability OR Sustainable) AND (Wellbeing OR Health).

20 papers fulfilled the criteria and were thus included in this review (Table 3). These papers were further analysed for the following information:

Table 3.

The 20 articles on health and sustainability in public meals fulfilling the five criteria for inclusion in this study.

- Aim;

- Public meal arena;

- Aspects of health;

- Aspects of sustainability;

- Motive for combining health and sustainability.

Table 4.

Main content of the included articles.

4. Results and Discussion

The primary aim has been to provide an explorative review of the scientific literature focusing on European research, where both health and sustainability in relation to public meals have been addressed. In total, 20 articles were analysed, and these are presented in Table 3.

By connecting Table 3 to Table 4 using the reference number, each reference may be easily identified. As shown in Table 4, the main public meal arena for discussing health and sustainability was the school, including preschool. School was the main arena in a total of 12 articles, a result also in line with previous studies, where the school has been the primary public meal arena investigated [61].

Our findings show that social and mental aspects of health were found to be addressed in only a few articles, e.g., in terms of social equality and overall well-being and growth. In for example paper No 2 school meal programs increase knowledge and awareness of norms around sustainable consumption to meet challenges in both health and sustainability. In papers No 11 and 19 school meals are said to be a tool to improve health in children across ethnic and socioeconomic groups. (Table 2). Commonly, health was understood in terms of physical health only, focusing on a healthy diet and pointing to the urge to eat according to national dietary guidelines. It was illustrated, for example in papers No 3, 4 and 11, as intake of fruit and vegetables, other nutritious food, and an adequate energy intake, often in the context of overweight and obesity among children.

Furthermore, sustainability was primarily dealt with in relation to environmental aspects, for example in paper No 5, 13, 14, 17 and 18; however, social and economic aspects were also mentioned in some of the selected articles, see No 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 10, 11, 15, 19 and 20. As in earlier studies [62,63], in selected papers for example No 11 and 13, sustainability was most often discussed in terms of food waste, but procurement and local production were also discussed in relation to both environmental and economic aspects in papers No 5, 10 and 15. The domination of the environmental aspect of sustainability has previously been criticized [64]. However, in this review, social and economic aspects were in papers No 6 and 10, to some extent, included primarily in terms of politics, welfare, and social justice, and to highlight the importance of including relevant actors (Table 4).

The study showed the different approaches to health and sustainability as well as ways of combining these aspects. Three main approaches could be identified, which were evident in some studies as exemplified below, and less apparent in others. The approaches identified are:

- -

- Health as embracing sustainability, where health is the point of departure and where sustainability is included as part of health. This is emphasized in relation to health promotion initiatives and how these could also be more sustainable, claiming that health should embrace both aspects. This is the content of papers No 14 and 19 where health and nutritional aspects of school meals also would include sustainability in the form of agricultural improvements or effectiveness. In papers No 16 and 17 health promotion in canteens may promote sustainability through environmental thinking and behaviours. Paper No 3 claims that increased consumption of fruit and vegetables as a part of a healthy diet will have a positive impact on sustainability.

- -

- Sustainability as embracing health,where sustainability is in focus and where health should be seen as part of sustainability. This was for example illustrated when focusing on sustainable food procurement which is then also motivated by better nutrition in terms of knowing where the food comes from and how it is produced in papers No 5, 10 and 15 This is also exemplified in studies were environmental challenges are in focus, which thereby requires new sources of nutrition and healthy food. In these cases, health is considered as part of the concept of sustainability. Examples of this are paper No 1 and 6, where food consumption in schools is in focus and paper No 7, where restaurant meals were studied. In paper No 13 infant food and food waste were focused upon.

- -

- Health and sustainability as separate concepts, where the link between them was unspecified or undefined. This could be exemplified by the stated role of the school meal to tackle societal challenges related to health and sustainability, although separately which is seen in paper No 8, 9, 10, 12 and 20 In papers No 2, 4, 18 meals in schools and preschool were used as a pedagogical tool, the learning role of the meal was highlighted in these studies, which included learning about both health and sustainability. For example, when investigating portion size both health, in terms of obesity and overweight, and sustainability, related to food waste, were identified as important factors.

Most often, a clear motivation for addressing or associating both concepts was lacking. When motivations were given, the need to include challenges related to both health and sustainability was put forward as them both relating to food behavior. This is clear in paper No 12 in which the role food scape is discussed in terms of impact and understanding of food behavior, but also in paper No 11 where school lunch was studied. Thereby, these studies also achieved a more holistic perspective. Another motive for combining health and sustainability was to gain a deeper understanding of the complexity of food behavior, which is seen in papers No 14, 19 and 20. According to the SDGs, WHO Non-communicable diseases country profiles 2018 [2], the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) [10] and the Lancet EAT report [8], there is an urgent need to increase scientific knowledge about how to embrace both health and sustainability aspects in the context of public meals.

Public meals play an important role in influencing people’s food behavior as well as maintaining or improving health [25,26]. Although public meals follow us through most stages of life, from cradle to grave, they have been more or less scientifically overlooked [65]. During recent decades, the focus on sustainability has increased in public debate and policymaking, also putting public meals on the agenda as an important means of achieving both health benefits and sustainability in society [66,67]. Earlier research has generally taken the health aspects of catering in public meals as the point of departure, while sustainability has not been a focus. Since the SDGs were formulated in 2015, a more integrated approach has been put forward. The fact that food and meals are related to most SDGs supports the need for further research and practical efforts directed toward sustainability in the area of public meals.

Based on the large number of meals served in public settings every day, these meals have the potential to target both health and sustainability challenges in relation to food and meals. It can be pointed out that the result of this study indicates an association rather than an integration between health and other concepts in all included articles, but especially in paper No 3, 5, 9, and 20. Additionally, health in terms of nutritional needs did not necessarily imply a positive environmental impact as discussed in paper No 10.

5. Concluding Discussion

It may be concluded that schools and hospitals are the most dominant arenas where both health and sustainability have been addressed in order to reach a more holistic perspective on food consumption of public meals. Three different approaches in combining health and sustainability have been found, which are:

“Health as embracing sustainability”, “Sustainability as embracing health” and “Health and sustainability as separate concepts”.

However, a clear motivation for addressing both health and sustainability is most often lacking.

This review includes 20 articles, a rather low number explained partly by the European focus, which can be seen as a limitation. However, even if articles from outside Europe had been found, the non-European context may have been confusing in terms of public meals since, at present, a common definition of public meals is lacking. Another explanation is that the research area of sustainability is quite new, with the 17 UN SDGs only being adopted in 2015. Furthermore, the focus on school/pre-school meals could be regarded as a limitation, but from the literature search, it was obvious that this is the most well-documented arena in terms of public meals.

The strength of the present study is its aim to explore studies covering the aspects of health and sustainability in the context of public meals at the same time. To our knowledge, this is the first paper with this focus. In conclusion, indicating an urgent need for research within all public meal arenas, between which conditions and challenges may vary, according to issues of health and sustainability. An increased number of publications also opens opportunities for systematic review analyses allowing the findings of separate papers to be compared and contrasted while providing a foundation for decision-making.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.H., C.L., M.N., V.O., E.R., H.S. and K.W; methodology, V.O. and E.R.; validation, E.R. and K.W.; formal analysis, K.H., C.L., M.N., V.O., E.R., H.S. and K.W.; investigation, K.H., C.L., M.N., V.O., E.R., H.S. and K.W.; writing—original draft preparation, K.H., C.L., M.N., V.O., E.R., H.S. and K.W.; writing—review and editing, A.M., M.N., E.R. and K.W.; visualization, V.O., E.R. and K.W.; project administration, K.W.; funding acquisition, K.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by The research environment MEAL (Food and Meals in Everyday Life), Kristianstad University, Sweden.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- WHO. Non-communicable diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 11 June 2019).

- WHO. Malnutrition. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malnutrition (accessed on 11 June 2019).

- WHO. European Food and Nutrition Action Plan. 2015–2020; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Elia, M.; Stratton, R.J.; Russell, C.; Green, C.; Pang, F. The Cost of Disease-Related Malnutrition in the UK and Economic Considerations for the Use of Oral Nutritional Supplements (ONS) in Adults; University of Southshampton: Southshampton, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Meijers, J.M.; Schols, J.M.; van Bokhorst-de van der Schueren, M.A.; Dassen, T.; Janssen, M.A.; Halfens, R.J. Malnutrition prevalence in The Netherlands: Results of the annual dutch national prevalence measurement of care problems. Br. J. Nutr. 2009, 101, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IPCC. Contribution to the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Available online: http://www.climatechange2013.org/report/ (accessed on 29 December 2019).

- Hedenus, F.; Wirsenius, S.; Johansson, D.J.A. The importance of reduced meat and dairy consumption for meeting stringent climate change targets. Clim. Chang. 2014, 124, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Jonell, M. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EIPRO. European Commission Joint Research Centre. 2006. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/environment/ipp/pdf/eipro_report.pdf (accessed on 29 December 2019).

- UN. Our Common Future, Chapter 2: Towards Sustainable Development. Available online: http://www.un-documents.net/ocf-02.htm (accessed on 17 November 2017).

- Edwards, J.S.A. The foodservice industry: Eating out is more than just a meal. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 27, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Global Goals. The 17 Goals. Available online: https://www.globalgoals.org/ (accessed on 31 October 2019).

- Williams, P.G. Meals in science and practice. In Interdisciplinary Research and Business Applications; Meiselman, H.L., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing Ltd.: Cambridge, UK, 2009; pp. 50–65. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, J.S.A.; Hartwell, H.J. Institutional meals. In Meals in Science and Practice. Interdisciplinary Research and Business Applications; Meiselman, H.L., Ed.; CRC Press, Woodhead publishing: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 102–127. [Google Scholar]

- Nordic Council of Ministers. Nordic Nutrition Recommendations 2012. Integrating nutrition and physical activity. Available online: https://norden.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:704251/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2019).

- Warde, A.; Martens, L. Eating Out: Social Differentiation, Consumption and Pleasure; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mattsson Sydner, Y.; Fjellström, C. Illuminating the (non-) meaning of food: Organization, power and responsibilities in public elderly care–a Swedish perspective. J. Foodserv. 2007, 18, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUFIC. Nutrition Standards for Healthy School Lunches in Europe. Available online: https://www.eufic.org/en/healthy-living/article/school-lunch-standards-in-europe (accessed on 13 March 2019).

- Storcksdieck, G.B.S.; Kardakis, T.; Wollgast, J.; Nelson, M.; Caldeira, S. Mapping of National School Food Policies across the EU28 plus Norway and Switzerland; JRC Science and Policy Reports: Luxembourg, 2014; ISBN 978-92-79-38402-8. ISSN 1018-5593. [Google Scholar]

- Caldeira, S.; Storcksdieck, G.B.S.; Bakogianni, J.; Gauci, C.; Calleja, A.; Furtadoet, A. Public Procurement of Food for Health—Technical Report; The School Setting: Luxembourg, 2017; ISBN 978-92-79-67465-5. ISSN 1018-5593. [Google Scholar]

- Grausne, J.; Quetel, A.K. Fakta om Offentliga Måltider 2018 Kartläggning av Måltider i Kommunalt Drivna Förskolor, Skolor Och Omsorgsverksamheter; Livsmedelsverket: Uppsala, Sweden, 2018; p. 25. ISSN 1104-7089. [Google Scholar]

- Gullberg, E. Food for future citizens: School meal culture in Sweden. Food, Culture and Society. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2006, 9, 337–343. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, C.E.L.; Harper, C.E. A history and review of school meal standards in the UK. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2009, 22, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, I.S.; Ness, A.R.; Hebditch, K.; Jones, L.R.; Emmett, P.M. Quality of food eaten in English primary schools: School dinners vs packed lunches. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 61, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.M.; Balkn, U.N.; Fürst, P.; Hasunen, K.; Jones, L.; Keller, U.; Melchior, J.C.; Mikkelsen, B.E.; Schauder, P.; Sivonen, L.; et al. Food and nutritional care in hospitals: How to prevent undernutrition–report and guidelines from the Council of Europe. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 20, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raulio, S.; Roos, E.; Prättälä, R. School and workplace meals promote healthy food habits. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13, 987–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BAPEN. Hospital Food as Treatment. Available online: https://www.bapen.org.uk/resources-and-education/education-and-guidance/clinical-guidance/hospital-food-as-treatment?showall=1 (accessed on 13 December 2019).

- Herbert, K.; Plugge, E.; Foster, C.; Doll, H. Prevalence of risk factors for non-communicable diseases in prison populations worldwide: A systematic review. Lancet 2012, 379, 1975–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazel, S.; Hope, T.; O’Donnell, I.; Jacoby, R. Unmet treatment needs of older prisoners: A primary care survey. Age Ageing 2004, 33, 396–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wangmo, T.; Handtke, V.; Bretschneider, W.; Elger, B.S. Improving the health of older prisoners: Nutrition and exercise in correctional institutions. J. Correct. Health Care 2018, 24, 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skotheim, S.; Handeland, K.; Kellevold, M.; Öyen, J.; Fröyland, L.; Lie, Ö.; Graff, I.E.; Baste, V.; Smith, T.J.; Dotson, L.; et al. Eating Patterns and Leisure-Time Exercise among Active Duty Military Personnel: Comparison to the Healthy People Objectives. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 113, 907–919. [Google Scholar]

- Crombie, A.P.; Funderburk, L.K.; Smith, T.J.; McGraw, S.M.; Walkers, L.A.; Champagne, C.M.; Allen, R.A.; Margolis, L.M.; McClung, H.L.; Young, A.J. Effects of modified foodservice practices in military dining facilities on Ad Libitum nutritional intake of US army soldiers. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 113, 920–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryegård, O. Offentlig marknad för livsmedel i Sverige samt import av livsmedel till aktörer i offentlig sektor. Available online: https://www.livsmedelsverket.se/globalassets/matvanor-halsa-miljo/maltider-vard-skola-omsorg/fakta-om-offentliga-maltider/rapport-lrf-offentlig-marknad-2013.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2019).

- DKAB Service AB. Hantera livs. Available online: http://www.dkab.se/ (accessed on 29 November 2019).

- EkoMatCentrum. Available online: http://ekomatcentrum.se/ (accessed on 29 November 2019).

- WHO. Constitution. Available online: https://www.who.int/about/mission/en/ (accessed on 13 May 2019).

- WHO. Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases; WHO Document Production Services: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; ISBN 978 92 4 156485 4. [Google Scholar]

- Elgar, F.J.; Craig, W.; Trites, S.J. Family dinners, communication and mental health in Canadian adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2013, 52, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utter, J.; Denny, S.; Roshini, P.J.; Moselen, E.; Dyson, B.; Clark, T. Family meals and adolescent emotional well-being: Findings from a national study. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2017, 49, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, S.; Wasielewska, A.; Raiswell, C.; Drummond, B. Exploring the meal-time experience in residential care settings for older people: An observational study. Health Soc. Care Community 2013, 21, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.; Dailami, N.; Weitkamp, E.; Salmon, D.; Kimberlee, R.; Morley, A.; Orme, J. Food sustainability education as a route to healthier eating: Evaluation of a multi-component school programme in English primary schools. Health Educ. Res. 2012, 27, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oostindjer, M.; Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Wang, Q.; Skuland, S.E.; Egelandsdal, B.; Amdam, G.V.; Schjøll, A.; Pachucki, M.C.; Rozin, P.; Stein, J.; et al. Are school meals a viable and sustainable tool to improve the healthiness and sustainability of children´s diet and food consumption? A cross-national comparative perspective. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 3942–3958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.; Pitt, H.; Oxford, L.; Bray, I.; Kimberlee, R.; Orme, J. Association between Food for Life, a whole setting healthy and sustainable food programme, and primary school children’s consumption of fruit and vegetables: A cross-sectional study in England. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balzaretti, C.M.; Ventura, V.; Ratti, S.; Ferrazzi, G.; Spallina, A.; Carruba, M.O.; Castrica, M. Improving the overall sustainability of the school meal chain: The role of portion sizes. Eat. Weight Disord.-Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2018, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxe, H.; Loftager Okkels, S.; Jensen, J. How to obtain forty percent less environmental impact by healthy, protein-optimized snacks for older adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickramasinghe, K.; Rayner, M.; Goldacre, M.; Townsend, N.; Scarborough, P. Environmental and nutrition impact of achieving new School Food Plan recommendations in the primary school meals sector in England. BMJ open 2017, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelmann, T.; Speck, M.; Rohn, H.; Bienge, K.; Langen, N.; Howell, E.; Göbel, C.; Friedrich, S.; Teitscheid, P.; Bowry, J.; et al. Sustainability assessment of out-of-home meals: Potentials and challenges of applying the indicator sets NAHGAST meal-basic and NAHGAST meal-pro. Sustainability 2018, 10, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, S.; Orme, J.; Pitt, H.; Jones, M. Food for Life: Evaluation of the impact of the Hospital Food Programme in England using a case study approach. JRSM Open 2017, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Mikkelsen, B.E. The association between organic school food policy and school food environment: Results from an observational study in Danish schools. Perspect. Public Health 2014, 134, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnino, R.; McWilliam, S. Food waste, catering practices and public procurement: A case study of hospital food systems in Wales. Food Policy 2011, 36, 823–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorsen, A.V.; Lassen, A.D.; Andersen, E.W.; Christensen, L.M.; Biltoft-Jensen, A.; Andersen, R.; Damsgaard, C.T.; Michaelsen, K.F.; Tetens, I. Plate waste and intake of school lunch based on the new Nordic diet and on packed lunches: A randomised controlled trial in 8-to 11-year-old Danish children. J. Nutr. Sci. 2015, 4, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelsen, B.E. Images of foodscapes: Introduction to foodscape studies and their application in the study of healthy eating out-of-home environments. Perspect. Public Health 2011, 131, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan-Fogarty, Y.; Becker, G.; Moles, R.; O’Regan, B. Backcasting to identify food waste prevention and mitigation opportunities for infant feeding in maternity services. Waste Manag. 2017, 61, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, M.; Breda, J. School food research: Building the evidence base for policy. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 958–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filippini, R.; De Noni, I.; Corsi, S.; Spigarolo, R.; Bocchi, S. Sustainable school food procurement: What factors do affect the introduction and the increase of organic food? Food Policy 2018, 76, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, S.; Cawood, J.; Dooris, M. Applying the whole-system settings approach to food within universities. Perspect. Public Health 2011, 131, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorsen, A.V.; Lassen, A.D.; Tetens, I.; Hels, O.; Mikkelsen, B.E. Long-term sustainability of a worksite canteen intervention of serving more fruit and vegetables. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13, 1647–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittman, D.W.; Parker, J.S.; Getz, B.R.; Jackson, C.M.; Le, T.A.; Riggs, S.B.; Shay, J.M. Cost-free and sustainable incentive increases healthy eating decisions during elementary school lunch. Int. J. Obes. 2012, 36, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Moore, L.; de Silva-Sanigorski, A.; Moore, S.N. A socio-ecological perspective on behavioural interventions to influence food choice in schools: Alternative, complementary or synergistic? Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 1000–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, S.; Jones, M.; Means, R.; Orme, J.; Pitt, H.; Salmon, D. Inter-sectoral Transfer of the Food for Life Settings Framework in England. Health Promot. Int. 2017, 33, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, F.; Brunori, G.; Di Iacovo, F.; Innocenti, S. Co-Producing Sustainability: Involving Parents and Civil Society in the Governance of School Meal Services. A Case Study from Pisa, Italy. Sustainability 2014, 6, 1643–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falasconi, L.; Vittuari, M.; Politano, A.; Segrè, A. Food Waste in School Catering: An Italian Case Study. Sustainability 2015, 7, 4745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias-Ferreira, C.; Santos, T.; Oliveira, V. Hospital food waste and environmental and economic indicators—A Portuguese case study. Waste Manag. 2015, 46, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallance, S.; Perkins, H.C.; Dixon, J.E. What is social sustainability? A clarification of concepts. Geoforum 2011, 42, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.S.; Hartwell, H.J.; Reeve, W.G.; Schafheitle, J. The diet of prisoners in England. Br. Food J. 2007, 109, 216–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamine, C. Sustainability and resilience in agrifood systems: Reconnecting agriculture, food and the environment. Sociol. Rural. 2015, 55, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirwan, J.; Maye, D.; Brunori, G. Acknowledging complexity in food supply chains when assessing their performance and sustainability. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 52, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).