Prevalence and Factors Associated with Burnout Syndrome among Primary Health Care Nursing Professionals: A Cross-Sectional Study †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Antunes, R.A. Centralidade do trabalho hoje. In A Sociologia No Horizonte do Século XXI; Ferreira, L.C., Ed.; Boitempo: São Paulo, Brazil, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ceolin, G.F. Crise do capital, precarização do trabalho e impactos no Serviço Social. Serv. Soc. Soc. 2014, 118, 239–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, R. Adeus ao trabalho? In Ensaio Sobre as Metamorfoses e A Centralidade no Mundo do Trabalho, 16th ed.; Cortez: São Paulo, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dejours, C. A Loucura do Trabalho: Estudo de Psicopatologia do Trabalho, 6th ed.; Cortez: São Paulo, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Merces, M.C.; Silva, D.S.; Lopes, R.A.; Lua, I.; Silva, J.K.; Oliveira, D.S.; Servo, M.L.S. Síndrome de Burnout em enfermeiras da atenção básica à saúde: Uma revisão integrativa. Rev. Epidemiol. Control. Infect. 2015, 5, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.L.; Dewe, P.J.; O’Driscoll, M.P. Estresse Organizacional. In Uma Revisão e Crítica da Teoria; Pesquisa e Aplicações: Sage, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M. Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry 2016, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willard-Grace, R.; Hessler, D.; Rogers, E.; Dubé, K.; Bodenheimer, T.; Grumbach, K. Team structure and culture are associated with lower burnout in primary care. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2014, 27, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merces, M.C.; Souza, D.S.S.; Lua, I.; Oliveira, D.S.; Souza, M.C. Burnout syndrome and abdominal adiposity among Primary Health Care nursing professionals. Psicol. Reflex Crit. 2016, 29, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chico-Barba, G.; Jiménez-Limas, K.; Sánchez-Jiménez, B.; Sámano, R.; Rodríguez-Ventura, A.L.; Castillo-Pérez, R.; Tolentino, M. Burnout and Metabolic Syndrome in Female Nurses, An Observational Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision (ICD-11). The Global Standard for Diagnostic Health Information; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job burnout. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cañadas-De la Fuente, G.A.; Vargas, C.; San Luis, C.; García, I.; Cañadas, G.R.; De la Fuente, E.I. Risk factors and prevalence of burnout syndrome in the nursing profession. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015, 52, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento Sobrinho, C.L.; Barros, D.S.; Tironi, M.O.S.; Marques Filho, E.S. Médicos de UTI, prevalência da Síndrome de Burnout, características sociodemográficas e condições de trabalho. Rev. Bras. Educ. Med. 2010, 34, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; Vargas, C.; De la Fuente, E.I.; Fernández-Castillo, R.; Canadas-De la Fuente, G.A. Age as a risk factor for burnout syndrome in nursing professionals: A meta-analytic study. Res. Nurs. Health 2017, 40, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, E.M.; De Martino, M.M.F. Preditores da síndrome de burnout em enfermeiros de unidade de terapia intensiva. Rev. Gaúcha Enferm. 2017, 38, e65354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

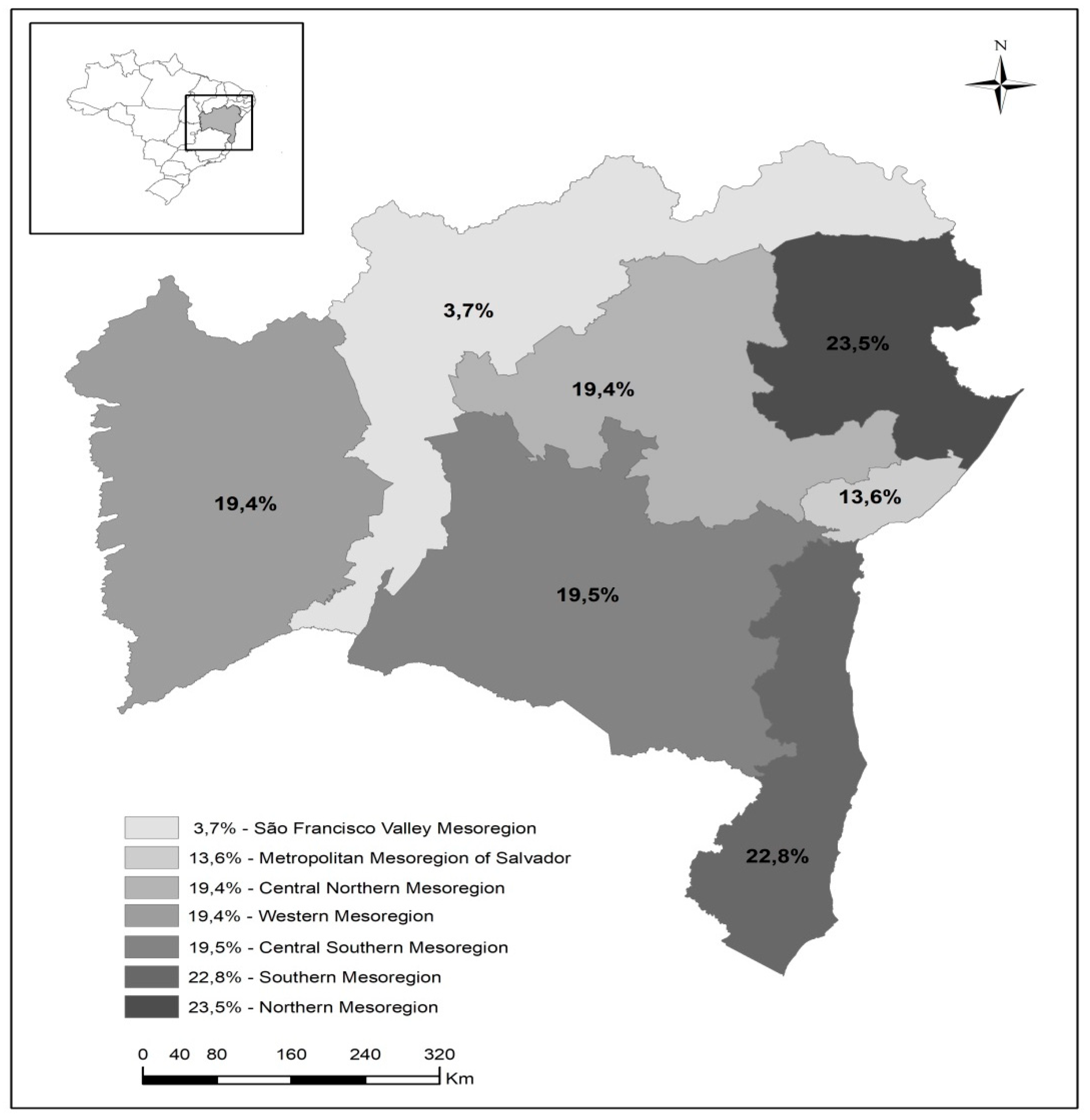

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Divisão Regional do Brasil em Mesorregiões e Microrregiões Geográficas; IBGE: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1990.

- Seigel, D.G.; Podgor, M.J.; Remaley, N.A. Acceptable values of kappa for comparison of two groups. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1992, 135, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. Maslach Burnout Inventory, 2nd ed.; Consulting Psychologist Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Tamayo, M.R. Relation between Burnout Syndrome and Organizational Values inthe Nursing Staff of Two Public Hospitals. Master’s Thesis, University of Brasília, Brasília, Brazil, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, D.S.; Magnago, R.F.; Sakae, T.M.; Magajewski, F.R. Prevalência da Síndrome de Burnout em trabalhadores de enfermagem de um hospital de grande porte da Região Sul do Brasil. Cad. De Saúde Pública 2009, 25, 1559–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez, A.J.; Graham, J.; Richards, M.A.; Cull, A.; Gregory, W.M. Mental health of hospital consultants: The effects of stress and satisfaction at work. Lancet 1996, 347, 724–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmer, D.W.; Lemeshow, S. Applied Logistic Regression; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho, L.M.S.; Scazufca, M.; Menezes, P.R. Methods for estimating prevalence ratios in crosssectional studies. Rev. Saúde Pública 2008, 42, 992–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, P.; Donalisio, M.; Barros, M.; Cesar, C.; Carandina, L.; Goldbaum, M. Association measures in cross-sectional studies with complex samplings: Odds ratio and prevalence ratio. Rev. Bras. Epidemiol. 2008, 11, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lua, I.; Araújo, T.M.; Santos, K.O.B.; Almeida, M.M.G. Factors associated with common mental disorders among female nursing professionals in primary health care. Psicol. Reflexão E Crítica 2018, 31, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lua, I.; Almeida, M.M.G.; Araújo, T.M.; Soares, J.F.S.; Santos, K.O.B. Autoavaliação negativa da saúde em trabalhadoras de enfermagem da atenção básica. Trab. Educ. Saúde. 2018, 16, 1301–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyrulnik, B. Les Vilains Petits Canards; Odile Jacob: Paris, France, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Amaral, J.F.; Ribeiro, J.P.; Paixão, D.X. Qualidade de vida no trabalho dos profissionais de enfermagem em ambiente hospitalar: Uma revisão integrativa. Rev. Espaço. Saúde. 2015, 16, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secco, I.A.O.; Robazzi, M.L.C.C.; Souza, F.E.A.; Shimizu, D.S. Cargas psíquicas de trabalho e desgaste dos trabalhadores de enfermagem de hospital de ensino do Paraná, Brasil. Rev. Elet. Saúde Ment. Álcool. Drog. 2010, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Merces, M.C.; Cordeiro, T.M.S.C.; Santana, A.I.C.; Lua, I.; Silva, D.S.; Alves, M.S.; D’Oliveira Júnior, A. Síndrome de burnout em trabalhadores de Enfermagem da Atenção Básica à Saúde. Rev. Baiana De Enferm. 2016, 30, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kalliath, T.; Morris, R. Job satisfaction among nurses, A predictor of burnout levels. J. Nurs. Adm. 2002, 32, 648–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenz, V.R.; Guirardello, E.B. The environment of professional practice and Burnout in nurses in primary healthcare. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2014, 22, 926–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khamisa, N.; Oldenburg, B.; Peltzer, K.; Ilic, D. Work Related Stress, Burnout, Job Satisfaction and General Health of Nurses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 652–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alameddine, M.; Mourad, Y.; Dimassi, H. A national study on nurses’ exposure to occupational violence in Lebanon: Prevalence, consequences and associated factors. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0137105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidotti, V.; Ribeiro, R.P.; Galdino, M.J.Q.; Martins, J.T. Burnout Syndrome and shift work among the nursing staff. Rev. Latino. Am. Enfermagem. 2018, 26, e3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starfield, B. Atenção Primária: Equilíbrio Entre Necessidades de Saúde, Serviços e Tecnologias; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2002.

- McHugh, M.D.; Stimpfel, A.W. Nurse reported quality of care: A measure of hospital quality. Res. Nurs. Health 2012, 35, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Yao, W.; Wang, W.; Li, H.; Lan, Y. Investigation of risk factors of psychological acceptance and Burnout syndrome among nurses in China. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2013, 19, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merces, M.C.; Gomes, A.M.T.; Guimarães, E.L.P.; Santana, A.I.C.; Silva, D.S.; Machado, Y.Y.; Couto, P.L.S.; França, L.C.M.; Figueiredo, V.P.; D’Oliveira Júnior, A. Burnout and metabolic conditions are professionals of nursing, A pilot study. Enferm. Bras. 2018, 17, 90–98. [Google Scholar]

- Zanelli, J.C. Estresse Nas Organizações de Trabalho. Compreesão e Intervenção Baseadas em Evidências; Artmed: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, H.H.; Yeh, C.Y.; Su, C.T.; Chen, C.J.; Peng, S.M.; Chen, R.Y. The effects of exercise program on burnout and metabolic syndrome components in banking and insurance workers. Ind. Health 2013, 51, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, K.S.; Lacaille, R.A.; Shearer, D.S. The acute affective response of Type A behavior pattern individuals to competitive and noncompetitive exercise. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 2003, 35, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, S.S.; Santos, P.G.; Passos, J.P. A síndrome de burnout no enfermeiro: Um estudo comparativo entre atenção básica e setores fechados hospitalares. J. Res. Fundam. Care 2010, 2, 381–384. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, E.S.; Santos, S.R.; Farias, J.Á.; Costa, M.B.S. Síndrome de burnout em enfermeiros na atenção básica: Repercussão na qualidade de vida. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 2014, 6, 1384–1395. [Google Scholar]

- Falgueras, M.V.; Munoz, C.C.; Pernas, F.O.; Sureda, J.C.; López, M.P.G.; Miralles, J.D. Burnout y trabajo en equipo en los profesionales de Atención Primaria. Aten Primaria 2015, 47, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Ferreira, N.N.; Lucca, S.R. Burnout syndrome in nursing assistants of a public hospital in the state of São Paulo. Rev. Bras. Epidemio. 2015, 18, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merces, M.C.; Lopes, R.A.; Silva, D.S.; Oliveira, D.S.; Lua, I.; Mattos, A.I.; D’Oliveira Júnior, A. Prevalência da Síndrome de Burnout em profissionais de enfermagem da atenção básica à saúde. Rev. Fund. Care Online 2017, 9, 208–214. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, A.; Farah, B.F.; Bustamante–Teixeira, M.T. Análise da prevalência da Síndrome de Burnout em profissionais da atenção primária em saúde. Trab. Educ. Sáude 2018, 16, 279–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cámara, R.S.; Cuesta, M.I.S. Prevalence of burnout in primary care nurses. Enfermería Clínica 2005, 15, 123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Golembiewski, R.T.; Munzenrider, R.; Carter, D. Phases of progressive burnout and their work site covariants, Critical issues in OD research and praxis. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 1983, 19, 461–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiter, M.P. Burnout as a development process, considerations of models. In Professional Burnout: Recents Developments in Theory and Research; Schaufeli, W.B., Maslach, C., Marek, T., Eds.; Taylor e Francis: Washington, DC, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Artalejo, F.; Graciani, A.; Guallar-Castillon, P.; León-Munoz, L.M.; Zuluaga, M.C.; López-Garcia, E.; Gutierrez-Fisac, J.L.; Taboada, J.M.; Aguilera, M.T.; Regidor, E.; et al. Rationale and methods of the study on nutrition and cardiovascular risk in Spain (ENRICA). Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2011, 64, 876–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimensions | n (%) | Average Points | Standard Deviation | Cronbach’s Alpha | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Moderate | High | ||||

| EE | 346 (30.8) | 461 (41.1) | 316 (28.1) | 22.4 | 6.68 | 0.82 |

| DP | 220 (19.6) | 403 (35.9) | 501 (44.5) | 9.6 | 3.99 | 0.79 |

| RPR | 40 (3.6) | 407 (36.2) | 677 (60.2) | 30.4 | 6.27 | 0.81 |

| Burnout Syndrome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | n (%) | P (%) b | PR c (CI 95%) d | p-Value e |

| Sociodemographic (Distal Block) | ||||

| Sex (n = 1125) | ||||

| Male | 136 (12.1) | 43 (31.6) | 1.00 | |

| Female | 989 (87.9) | 162 (16.4) | 0.52 (0.39–0.69) | <0.01 * |

| Age (n = 1125) | ||||

| Up to 35 years old | 587 (52.2) | 101 (17.3) | 1.00 | |

| 36 years old or older | 538 (47.8) | 104 (19.4) | 1.12 (0.87–1.43) | 0.36 |

| Ethnicity (n = 1098) a | ||||

| Non-black people | 246 (22.4) | 61 (24.8) | 1.00 | |

| Black people | 852 (77.6) | 136 (16.0) | 0.64 (0.49–0.84) | <0.01 * |

| Marital Ssatus (n = 1125) | ||||

| Not married | 606 (53.9) | 106 (17.6) | 1.00 | |

| Married | 519 (46.1) | 99 (19.1) | 1.08 (0.84–1.39) | 0.50 |

| Place of residence (n = 1125) | ||||

| Urban | 941 (83.6) | 144 (15.4) | 1.00 | |

| Rural | 184 (16.4) | 61 (33.3) | 2.17 (1.68–2.79) | <0.01 * |

| Children (n = 1125) | ||||

| No | 454 (40.4) | 89 (16.7) | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 671 (59.6) | 116 (17.3) | 0.87 (0.68–1.12) | 0.30 |

| Economic situation (n = 1125) | ||||

| Satisfied | 573 (50.9) | 87 (15.2) | 1.00 | |

| Dissatisfied | 552 (49.1) | 118 (21.5) | 1.40 (1.09–1.81) | <0.01 * |

| Lifestyle (proximal block) | ||||

| Routine of physical activities (n = 1125) | ||||

| Yes | 639 (56.8) | 88 (13.8) | 1.00 | |

| No | 486 (43.2) | 117 (24.1) | 1.74 (1.35–2.23) | <0.01 * |

| Smoking habit (n = 1125) | ||||

| No | 992 (88.2) | 157 (15.9) | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 133 (11.8) | 48 (36.1) | 2.27 (1.73–2.96) | <0.01 * |

| Alcohol consumption (n = 1125) | ||||

| No | 1083 (96.3) | 194 (18.0) | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 42 (3.7) | 11 (26.2) | 1.45 (0.86–2.45) | 0.18 |

| Healthy eating (n = 1125) | ||||

| Yes | 590 (52.4) | 96 (16.3) | 1.00 | |

| No | 535 (47.6) | 109 (20.5) | 1.25 (0.98–1.61) | 0.07 |

| Satisfaction with physical form (n = 1125) | ||||

| Yes | 571 (50.8) | 77 (13.5) | 1.00 | |

| No | 554 (49.2) | 128 (23.2) | 1.71 (1.32–2.21) | <0.01 * |

| Last consultation with health professional (n = 1125) | ||||

| Less than 12 months | 924 (82.1) | 164 (17.8) | 1.00 | |

| More than 12 months | 201 (17.9) | 41 (20.4) | 1.14 (0.84–1.55) | 0.40 |

| Quality of life (n = 1125) | ||||

| Good | 836 (74.3) | 147 (17.6) | 1.00 | |

| Poor | 289 (25.7) | 58 (20.1) | 1.14 (0.86–1.49) | 0.35 |

| Burnout Syndrome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | n (%) | P (%) a | PR b (CI 95%) c | p-Value d |

| Labour (intermediate block) | ||||

| Profession (n = 1125) | ||||

| Nurse | 455 (40.4) | 80 (17.8) | 1.00 | |

| Nursing technician | 670 (59.6) | 125 (18.7) | 1.05 (081–1.35) | 0.70 |

| Satisfaction with current occupation (n = 1125) | ||||

| Yes | 987 (87.7) | 154 (15.7) | 1.00 | |

| No | 138 (12.3) | 51 (37.0) | 2.35 (1.81–3.06) | <0.01 * |

| Occupation time in PHC (n = 1125) | ||||

| Up to 4 years | 555 (49.3) | 83 (15.0) | 1.00 | |

| 5 years or more | 570 (50.7) | 122 (21.4) | 1.42 (1.10–1.83) | <0.01 * |

| Work bond (n = 1125) | ||||

| Stable | 866 (77.0) | 159 (18.4) | 1.00 | |

| Precarious | 259 (23.0) | 46 (18.0) | 0.97 (0.72–1.31) | 0.88 |

| Rest break (n = 1125) | ||||

| Yes | 672 (59.7) | 103 (15.3) | 1.00 | |

| No | 453 (40.3) | 102 (22.7) | 1.48 (1.15–1.89) | <0.01 * |

| Submitted to work-related aggression (n = 1125) | ||||

| No | 751 (66.8) | 103 (13.8) | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 374 (33.2) | 102 (27.3) | 1.98 (1.55–2.52) | <0.01 * |

| Night shift (n = 1125) | ||||

| No | 894 (79.5) | 135 (15.2) | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 231 (20.5) | 70 (30.3) | 2.00 (1.55–2.56) | <0.01 * |

| Ventilation condition (n = 1125) | ||||

| Satisfactory | 662 (58.8) | 115 (17.5) | 1.00 | |

| Poor | 463 (41.2) | 90 (19.4) | 1.11 (0.87–1.43) | 0.40 |

| Temperature condition (n = 1125) | ||||

| Satisfactory | 602 (53.5) | 106 (17.6) | 1.00 | |

| Poor | 523 (46.5) | 99 (19.0) | 1.08 (0.84–1.38) | <0.01 * |

| Lighting condition (n = 1125) | ||||

| Satisfactory | 1038 (92.3) | 185 (17.9) | 1.00 | |

| Poor | 87 (7.7) | 20 (23.3) | 1.30 (0.87–1.95) | 0.21 |

| Technical resources & equipment (n = 1125) | ||||

| Satisfactory | 543 (48.3) | 87 (16.1) | 1.00 | |

| Poor | 582 (51.7) | 118 (20.3) | 1.27 (0.98–1.63) | 0.06 |

| Personal protective equipment (n = 1125) | ||||

| Satisfactory | 599 (53.2) | 112 (18.8) | 1.00 | |

| Poor | 526 (46.8) | 93 (17.7) | 0.95 (0.74–1.21) | 0.66 |

| Collective protective equipment (n = 1125) | ||||

| Satisfactory | 509 (45.2) | 100 (19.7) | 1.00 | |

| Poor | 616 (54.8) | 105 (17.1) | 0.87 (0.68–1.11) | 0.27 |

| Noise (n = 1125) | ||||

| Negligible | 608 (54.0) | 113 (18.7) | 1.00 | |

| Unbearable | 517 (46.0) | 92 (17.8) | 0.95 (0.74–1.22) | 0.71 |

| Factors Associated with Burnout Syndrome | PRadjusted | CI (95%) |

|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | 0.62 | (0.47–0.83) |

| Place of residence | 2.35 | (1.79–3.09) |

| Economic situation | 1.40 | (1.06–1.86) |

| Satisfaction with current occupation | 1.75 | (1.31–2.33) |

| Submitted to work-related aggression | 1.60 | (1.23–2.08) |

| Rest break | 1.83 | (1.41–2.37) |

| Technical Resources and Equipment | 1.37 | (1.06–1.77) |

| Night shift | 1.49 | (1.14–1.96) |

| Physical activity practice | 1.72 | (1.28–2.31) |

| Smoking habit | 1.82 | (1.35–2.45) |

| Satisfaction with physical form | 1.34 | (1.01–1.79) |

| Area under the ROC curve | 0.80 | |

| Goodness-of-fit test ¥ | 0.81 | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Merces, M.C.d.; Coelho, J.M.F.; Lua, I.; Silva, D.d.S.e.; Gomes, A.M.T.; Erdmann, A.L.; Oliveira, D.C.d.; Lago, S.B.; Santana, A.I.C.; Silva, D.A.R.d.; et al. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Burnout Syndrome among Primary Health Care Nursing Professionals: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 474. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020474

Merces MCd, Coelho JMF, Lua I, Silva DdSe, Gomes AMT, Erdmann AL, Oliveira DCd, Lago SB, Santana AIC, Silva DARd, et al. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Burnout Syndrome among Primary Health Care Nursing Professionals: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(2):474. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020474

Chicago/Turabian StyleMerces, Magno Conceição das, Julita Maria Freitas Coelho, Iracema Lua, Douglas de Souza e Silva, Antonio Marcos Tosoli Gomes, Alacoque Lorenzini Erdmann, Denize Cristina de Oliveira, Sueli Bonfim Lago, Amália Ivine Costa Santana, Dandara Almeida Reis da Silva, and et al. 2020. "Prevalence and Factors Associated with Burnout Syndrome among Primary Health Care Nursing Professionals: A Cross-Sectional Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 2: 474. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020474

APA StyleMerces, M. C. d., Coelho, J. M. F., Lua, I., Silva, D. d. S. e., Gomes, A. M. T., Erdmann, A. L., Oliveira, D. C. d., Lago, S. B., Santana, A. I. C., Silva, D. A. R. d., Servo, M. L. S., Sobrinho, C. L. N., Marques, S. C., Figueiredo, V. P., Peres, E. M., Souza, M. C. d., França, L. C. M., Maciel, D. M. C., Peixoto, Á. R. S., ... Júnior, A. D. (2020). Prevalence and Factors Associated with Burnout Syndrome among Primary Health Care Nursing Professionals: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(2), 474. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020474