Improving Knowledge that Alcohol Can Cause Cancer is Associated with Consumer Support for Alcohol Policies: Findings from a Real-World Alcohol Labelling Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

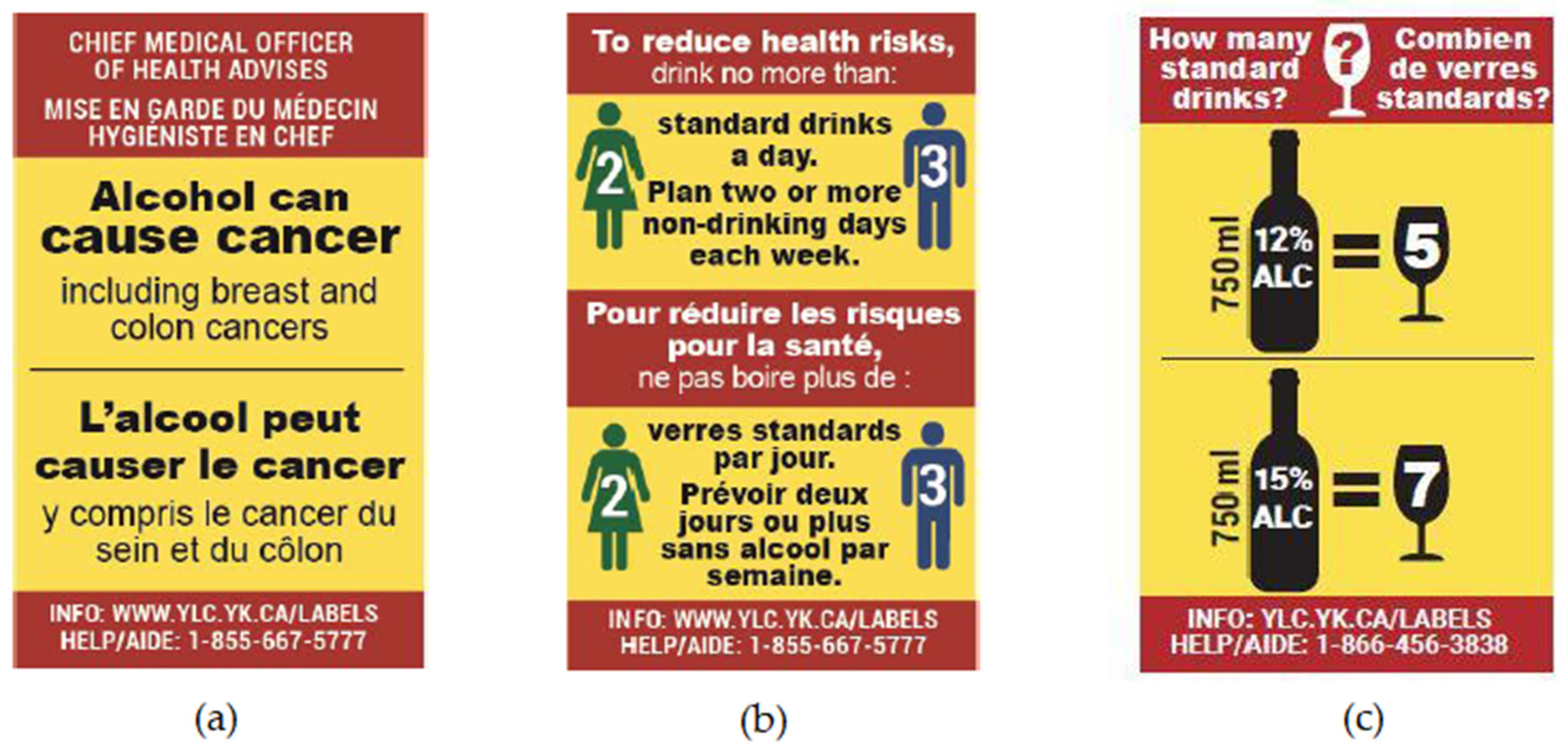

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Knowledge of Alcohol as a Carcinogen

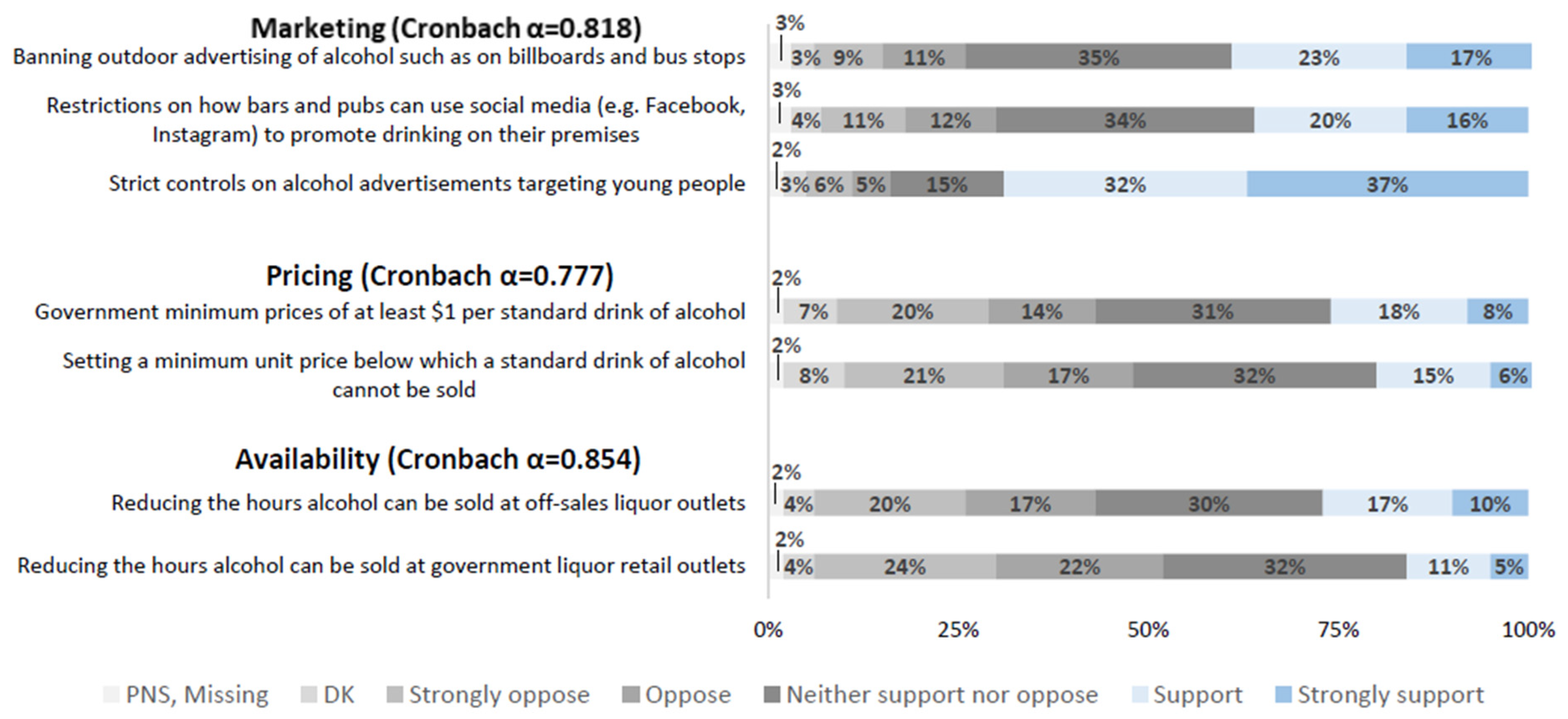

2.3.2. Support for Alcohol Policies

2.3.3. Socio-Demographics

2.3.4. Other Covariates

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Associations Between Knowledge of Alcohol as a Carcinogen and Support for Alcohol Policies

3.2. Associations between Increases in Knowledge of Alcohol as A Carcinogen and Alcohol Policies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/global_alcohol_report/gsr_2018/en/ (accessed on 11 October 2019).

- International Agency of Research on Cancer. Alcohol Consumption and Ethyl Carbamate. IARC Monogr. Eval. Carcinog. Risks Humans 2010, 96, 1–1379. Available online: https://monographs.iarc.fr/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/mono96.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2019).

- International Agency of Research on Cancer. Personal Habits and Indoor Combustions. IARC Monogr. Eval. Carcinog. Risks Humans. 2010, 100E, pp. 1–538. Available online: https://monographs.iarc.fr/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/mono100E.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2019).

- Bagnardi, V.; Rota, M.; Botteri, E.; Tramacere, I.; Islami, F.; Fedirko, V.; Scotti, L.; Jenab, M.; Turati, F.; Pasquali, E.; et al. Alcohol consumption and site-specific cancer risk: A comprehensive dose-response meta-analysis. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 112, 580–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Burden of Disease 2016 Alcohol Collaborators. Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2018, 392, 1015–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.J.; Myung, S.K.; Lee, J.H. Light Alcohol Drinking and Risk of Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Cancer. Res. Treat. 2018, 50, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthey, J.; Shield, K.D.; Rylett, M.; Hasan, O.S.M.; Probst, C.; Rehm, J. Global alcohol exposure between 1990 and 2017 and forecasts until 2030: A modelling study. Lancet 2019, 393, 2493–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Canada. Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs (CTADS) Survey: 2017 Detailed Tables. 2019. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canadian-tobacco-alcohol-drugs-survey/2017-summary/2017-detailed-tables.html#t17 (accessed on 25 October 2019).

- Shield, K.D.; Rylett, M.; Gmel, G.; Gmel, G.; Kehoe-Chan, T.A.; Rehm, J. Global alcohol exposure estimates by country, territory and region for 2005—A contribution to the Comparative Risk Assessment for the 2010 Global Burden of Disease Study. Addiction 2013, 108, 912–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. Table 183-0023: Sales and Per Capita Sales of Alcoholic Beverages by Liquor Authorities and Other Retail Outlets, by Value, Volume, and Absolute Volume. 2017. Available online: www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/a26?lang=eng&id=1830023 (accessed on 25 October 2019).

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Alcohol Harm in Canada: Examining Hospitalizations Entirely Caused by Alcohol and Strategies to Reduce Alcohol Harm. Available online: https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/report-alcohol-hospitalizations-en-web.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2019).

- Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction. Canadian Substance Use Costs and Harms Scientific Working Group. 2018. Available online: https://www.ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2019-04/CSUCH-Canadian-Substance-Use-Costs-Harms-Report-2018-en.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2019).

- Canadian Cancer Society. Drinking Habits and Perceived Impact of Alcohol Consumption [Survey Conducted by Leger]; Cancer Care Ontario: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Buykx, P.; Li, J.; Gavens, L.; Lovatt, M.; Gomes de Matos, E.; Holmes, J.; Meier, P. An Investigation of Public Knowledge of the Link between Alcohol and Cancer; University of Sheffield and Cancer Research: Sheffield, UK, 2015; Available online: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/sites/default/files/an_investigation_of_public_knowledge_of_the_link_between_alcohol_and_cancer_buykx_et_al.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2019).

- Cheeta, S.; Halil, A.; Kenny, M.; Sheehan, E.; Zamyadi, R.; Williams, A.L.; Webb, L. Does perception of drug-related harm change with age? A cross-sectional online survey of young and older people. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e021109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehm, J.; Lachenmeier, D.W.; Room, R. Why does society accept a higher risk for alcohol than for other voluntary or involuntary risks? BMC Med. 2014, 12, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Lancet. Changing the conversation to make drug use safer. Lancet 2018, 391, 1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, S.; Gmel, G.; Mohler-Kuo, M. Light and heavy drinking in jurisdictions with different alcohol policy environments. Int. J. Drug Policy 2019, 65, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vineis, P.; Wild, C.P. Global cancer patterns: Causes and prevention. Lancet 2014, 383, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, T.K.; Cook, W.K.; Karriker-Jaffe, K.J.; Patterson, D.; Kerr, W.C.; Xuan, Z.; Naimi, T.S. The Relationship Between the U.S. State Alcohol Policy Environment and Individuals’ Experience of Secondhand Effects: Alcohol Harms Due to Others’ Drinking. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2019, 43, 1234–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, P.; Chisholm, D.; Fuhr, D.C. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of policies and programmes to reduce the harm caused by alcohol. Lancet 2009, 373, 2234–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babor, T.; Caetano, R.; Casswell, S.; Edwards, G.; Giesbrecht, N.; Hill, L.; Homel, R.; Osterberg, E.; Rehm, J.; Room, R.; et al. Alcohol: No Ordinary Commodity—Research and Public Policy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, R.; Henn, C.; Lavoie, D.; O’Connor, R.; Perkins, C.; Sweeney, K.; Greaves, F.; Ferguson, B.; Beynon, C.; Belloni, A.; et al. A rapid evidence review of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of alcohol control policies: An English perspective. Lancet 2017, 389, 1558–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisholm, D.; Moro, D.; Bertram, M.; Pretorius, C.; Gmel, G.; Shield, K.; Rehm, J. Are the “Best Buys” for Alcohol Control Still Valid? An Update on the Comparative Cost-Effectiveness of Alcohol Control Strategies at the Global Level. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2018, 79, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, J.; Meng, Y.; Meier, P.S.; Brennan, A.; Angus, C.; Campbell-Burton, A.; Guo, Y.; Hill-McManus, D.; Purshouse, R.C. Effects of minimum unit pricing for alcohol on different income and socioeconomic groups: A modelling study. Lancet 2014, 383, 1655–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, J.; Giesbrecht, N.; Rehm, J.; Bekmuradov, D. Are Alcohol Prices and Taxes an Evidence-Based Approach to Reducing Alcohol-Related Harm and Promoting Public Health and Safety—A Literature Review Conference Report: Beyond the Buzzword: Problematising Drugs. Contemp. Drug Probs. 2012, 39, 7–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Room, R.; Schmidt, L.; Rehm, J.; Makela, P. International regulation of alcohol. Br. Med. J. 2008, 337, a2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenaar, A.C.; Salois, M.J.; Komro, K.A. Effects of beverage alcohol price and tax levels on drinking: A meta-analysis of 1003 estimates from 112 studies. Addiction 2009, 104, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockwell, T.; Auld, M.C.; Zhao, J.; Martin, G. Does minimum pricing reduce alcohol consumption? The experience of a Canadian province. Addiction 2012, 107, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockwell, T.; Zhao, J.; Martin, G.; Macdonald, S.; Vallance, K.; Treno, A.; Ponicki, W.; Tu, A.; Buxton, J. Minimum alcohol prices and outlet densities in British Columbia, Canada: Estimated impacts on alcohol-attributable hospital admissions. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 2014–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moskalewicz, J.; Wieczorek, Ł.; Karlsson, T.; Österberg, E. Social support for alcohol policy: Literature review. Drugs Educ. Prev. Policy 2013, 20, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechey, R.; Burge, P.; Mentzakis, E.; Suhrcke, M.; Marteau, T.M. Public acceptability of population-level interventions to reduce alcohol consumption: A discrete choice experiment. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 113, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hope, A. The ebb and flow of attitudes and policies on alcohol in Ireland 2002–2010. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2014, 33, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettigrew, S.; Hafekost, C.; Jongenelis, M.; Pierce, H.; Chikritzhs, T.; Stafford, J. Behind Closed Doors: The Priorities of the Alcohol Industry as Communicated in a Trade Magazine. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, N.; Buykx, P.; Shevills, C.; Sullivan, C.; Clark, L.; Newbury-Birch, D. Population Level Effects of a Mass Media Alcohol and Breast Cancer Campaign: A Cross-Sectional Pre-Intervention and Post-Intervention Evaluation. Alcohol Alcohol. 2018, 53, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, S.; Holmes, J.; Gavens, L.; de Matos, E.G.; Li, J.; Ward, B.; Hooper, L.; Dixon, S.; Buykx, P. Awareness of alcohol as a risk factor for cancer is associated with public support for alcohol policies. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buykx, P.; Gilligan, C.; Ward, B.; Kippen, R.; Chapman, K. Public support for alcohol policies associated with knowledge of cancer risk. Int. J. Drug Policy 2015, 26, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, A.S.P.; Meyer, M.K.H.; Dalum, P.; Krarup, A.F. Can a mass media campaign raise awareness of alcohol as a risk factor for cancer and public support for alcohol related policies? Prev. Med. 2019, 126, 105722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, M.A.; Loken, B.; Hornik, R.C. Use of mass media campaigns to change health behaviour. Lancet 2010, 376, 1261–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy to Reduce the Harmful Use of Alcohol; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; Available online: https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/msbalcstragegy.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2019).

- World Health Organization. Alcohol Labelling: A Discussion Document on Policy Options; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2017; Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/343806/WH07_Alcohol_Labelling_full_v3.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2019).

- Brewer, N.T.; Parada, H.; Hall, M.G.; Boynton, M.H.; Noar, S.M.; Ribisl, K.M. Understanding Why Pictorial Cigarette Pack Warnings Increase Quit Attempts. Ann. Behav. Med. 2019, 53, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, T. Warning labels: Evidence on harm reduction from long-term American surveys. In Alcohol: Minimizing the Harm; Plant, M., Single, E., Stockwell, T., Eds.; Free Association Books: London, UK, 1997; pp. 105–125. [Google Scholar]

- Al-hamdani, M.; Smith, S. Alcohol warning label perceptions: Emerging evidence for alcohol policy. Can. J. Public Health 2015, 106, e395–e400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Hamdani, M.; Smith, S.M. Alcohol Warning Label Perceptions: Do Warning Sizes and Plain Packaging Matter? J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2017, 78, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jongenelis, M.; Pratt, I.S.; Slevin, T.; Pettigrew, S. Effectiveness of Warning Labels at Increasing Awareness of Alcohol-Related Cancer Risk Among Heavy Drinkers. J. Glob. Oncol. 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, S.; Jongenelis, M.I.; Glance, D.; Chikritzhs, T.; Pratt, I.S.; Slevin, T.; Liang, W.; Wakefield, M. The effect of cancer warning statements on alcohol consumption intentions. Health Educ. Res. 2016, 31, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Cancer Statistics Advisory Committee. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2018; Canadian Cancer Society: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018; Available online: http://www.cancer.ca/~/media/cancer.ca/CW/cancer%20information/cancer%20101/Canadian%20cancer%20statistics/Canadian-Cancer-Statistics-2018-EN.pdf?la=en (accessed on 4 October 2019).

- Blackwell, A.K.M.; Drax, K.; Attwood, A.S.; Munafo, M.R.; Maynard, O.M. Informing drinkers: Can current UK alcohol labels be improved? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018, 192, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, D. Health warning messages on tobacco products: A review. Tob. Control 2011, 20, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobin, E.; Vallance, K.; Zuo, F.; Stockwell, T.; Rosella, L.; Simniceanu, A.; White, C.; Hammond, D. Testing the Efficacy of Alcohol Labels with Standard Drink Information and National Drinking Guidelines on Consumers’ Ability to Estimate Alcohol Consumption. Alcohol Alcohol. 2018, 53, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Moreno, J.M.; Harris, M.E.; Breda, J.; Moller, L.; Alfonso-Sanchez, J.L.; Gorgojo, L. Enhanced labelling on alcoholic drinks: Reviewing the evidence to guide alcohol policy. Eur. J. Public Health 2013, 23, 1082–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strahan, E.J.; White, K.; Fong, G.T.; Fabrigar, L.R.; Zanna, M.P.; Cameron, R. Enhancing the effectiveness of tobacco package warning labels: A social psychological perspective. Tob. Control 2002, 11, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallance, K.; Romanovska, I.; Stockwell, T.; Hammond, D.; Rosella, L.; Hobin, E. “We Have a Right to Know”: Exploring Consumer Opinions on Content, Design and Acceptability of Enhanced Alcohol Labels. Alcohol Alcohol. 2018, 53, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wettlaufer, A. Can a Label Help me Drink in Moderation? A Review of the Evidence on Standard Drink Labelling. Subst. Use Misuse 2018, 53, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobin, E.; Weerasinghe, A.; Vallance, K.; Hammond, D.; McGavock, J.; Greenfield, T.; Schoueri-Mychasiw, N.; Paradis, C.; Zhao, J.; Stockwell, T. Testing Alcohol Labels as a Tool to Communicate Cancer Risk to Drinkers: A Real-World Quasi-Experimental Study. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. in press.

- Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. Cancer Control Snapshot 5: Alcohol Use and Cancer in Canada. Available online: http://www.cancerview.ca/idc/groups/public/documents/webcontent/rl_crc_snapshot_5.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2019).

- Sanderson, S.C.; Waller, J.; Jarvis, M.J.; Humphries, S.E.; Wardle, J. Awareness of lifestyle risk factors for cancer and heart disease among adults in the UK. Patient Educ. Couns. 2009, 74, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallance, K.; Stockwell, T.; Hammond, D.; Shokar, S.; Schoueri-Mychasiw, N.; Greenfield, T.K.; McGavock, J.; Zhao, J.; Weerasinghe, A.; Hobin, E. Testing the Effectiveness of Enhanced Alcohol Warning Labels and Modifications resulting from alcohol industry interference in Yukon, Canada: Protocol for a Pre-Post Quasi-Experimental Study. J. Med Internet Res. in press.

- Austen, I.; Yukon Government Gives in to Liquor Industry on Warning Label Experiment. New York Times. 6 January 2018. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/06/world/canada/yukon-liquor-alcohol-warnings.html (accessed on 11 October 2019).

- Statistics Canada. Census Profile, 2016 Census: Northwest Territories [Territory] and Canada [Country]. 2016. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=PR&Code1=61&Geo2=PR&Code2=01&SearchText=northwest&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&B1=All&TABID=1&type=0 (accessed on 20 November 2019).

- Statistics Canada. Census Profile, 2016 Census: Yukon [Economic Region], Yukon and Yukon [Territory]. 2016. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=ER&Code1=6010&Geo2=PR&Code2=60&SearchText=Yukon&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&B1=All&GeoLevel=PR&GeoCode=6010&TABID=1&type=0 (accessed on 20 November 2019).

- What We Heard. Yukon Liquor Act Progress Report. Available online: https://yukon.ca/sites/yukon.ca/files/ylc-what-we-heard-liquor-act.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2019).

- Weiss, B.D.; Mays, M.Z.; Martz, W.; Castro, K.M.; DeWalt, D.A.; Pignone, M.P.; Mockbee, J.; Hale, F.A. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: The newest vital sign. Ann. Fam. Med. 2005, 3, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heeb, J.L.; Gmel, G. Measuring alcohol consumption: A comparison of graduated frequency, quantity frequency, and weekly recall diary methods in a general population survey. Addict. Behav. 2005, 30, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butt, P.; Beirness, D.; Cesa, F.; Gliksman, L.; Paradis, C.; Stockwell, T. Alcohol and Health in Canada: A Summary of Evidence and Guidelines for Low-Risk Drinking; Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rehm, J.; Greenfield, T.K.; Walsh, G.; Xie, X.; Robson, L.; Single, E. Assessment methods for alcohol consumption, prevalence of high risk drinking and harm: A sensitivity analysis. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1999, 28, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys, 7th ed.; The American Association for Public Opinion Research: Lenexa, KS, USA, 2011; Available online: https://www.esomar.org/uploads/public/knowledge-and-standards/codes-and-guidelines/ESOMAR_Standard-Definitions-Final-Dispositions-of-Case-Codes-and-Outcome-Rates-for-Surveys.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2019).

- Meier, P.S.; Holmes, J.; Angus, C.; Ally, A.K.; Meng, Y.; Brennan, A. Estimated Effects of Different Alcohol Taxation and Price Policies on Health Inequalities: A Mathematical Modelling Study. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1001963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, C.; Vallance, K.; Wettlaufer, A.; Stockwell, T.; Giesbrecht, N.; April, N.; Asbridge, M.; Callaghan, R.; Cukier, S.; Davis-MacNevin, P.; et al. Reducing Alcohol-Related Harms and Costs in Northwest Territories: A Policy Review; Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, University of Victoria: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chow, C.; Vallance, K.; Wettlaufer, A.; Stockwell, T.; Giesbrecht, N.; April, N.; Asbridge, M.; Callaghan, R.; Cukier, S.; Davis-MacNevin, P.; et al. Reducing Alcohol-Related Harms and Costs in Yukon: A Policy Review; Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, University of Victoria: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Holmila, M.; Mustonen, H.; Österberg, E.; Raitasalo, K. Public opinion and community-based prevention of alcohol-related harms. Addict. Res. Theory 2009, 17, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterberg, E.; Lindeman, M.; Karlsson, T. Changes in alcohol policies and public opinions in Finland 2003-2013. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2014, 33, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenfield, T.K.; Karriker-Jaffe, K.J.; Giesbrecht, N.; Kerr, W.C.; Ye, Y.; Bond, J. Second-hand drinking may increase support for alcohol policies: New results from the 2010 National Alcohol Survey. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2014, 33, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macdonald, S.; Stockwell, T.; Luo, J. The relationship between alcohol problems, perceived risks and attitudes toward alcohol policy in Canada. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2011, 30, 652–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, T.K.; Ye, Y.; Giesbrecht, N. Alcohol Policy Opinions in the United States over a 15-Year Period of Dynamic per Capita Consumption Changes: Implications for Today’s Public Health Practice. Contemp. Drug Probl. 2007, 34, 649–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lovatt, M.; Eadie, D.; Dobbie, F.; Meier, P.; Holmes, J.; Hastings, G.; MacKintosh, A.M. Public attitudes towards alcohol control policies in Scotland and England: Results from a mixed-methods study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 177, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, C.; Room, R.; Livingston, M. Mapping Australian public opinion on alcohol policies in the new millennium. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2009, 28, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, J.; Squires, J.; Parkinson, T. Public Perceptions of Alcohol Pricing; Home Office: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Diepeveen, S.; Ling, T.; Suhrcke, M.; Roland, M.; Marteau, T.M. Public acceptability of government intervention to change health-related behaviours: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheideler, J.K.; Klein, W.M.P. Awareness of the Link between Alcohol Consumption and Cancer across the World: A Review. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2018, 27, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.; Locker, E. Defensive responses to an emotive anti-alcohol message. Psychol. Health 2009, 24, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Knowledge of Alcohol as a Carcinogen | ||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Not Caused by Alcohol (N = 1177) | Caused by Alcohol (N = 553) |

| N (%) | N (%) | |

| Wave of initial recruitment *** | ||

| 1 | 390 (33.14) | 127 (22.97) |

| 2 | 516 (43.84) | 295 (53.35) |

| 3 | 271 (23.02) | 131 (23.69) |

| Site * | ||

| Intervention | 697 (59.22) | 359 (64.92) |

| Comparison | 480 (40.78) | 194 (35.08) |

| Age [Mean (SD)] | 44.82 (14.32) | 44.65 (14.53) |

| Age Categories | ||

| 19–24 | 92 (7.82) | 45 (8.14) |

| 25–44 | 480 (40.78) | 228 (41.23) |

| 45+ | 605 (51.40) | 280 (50.63) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 799 (67.88) | 386 (69.80) |

| Aboriginal | 225 (19.12) | 104 (18.81) |

| Other | 153 (13.00) | 63 (11.39) |

| Sex ** | ||

| Male | 622 (52.85) | 255 (46.11) |

| Female | 555 (47.15) | 298 (53.89) |

| Education Levels *** | ||

| Low (Completed high school or less) | 241 (20.48) | 88 (15.91) |

| Medium (Trades or college certificate, some university or university certificate below Bachelor) | 420 (35.68) | 171 (30.92) |

| High (Bachelor degree or higher) | 445 (37.81) | 266 (48.10) |

| Unknown (DK, PNS, Missing) | 71 (6.03) | 28 (5.06) |

| Income Levels | ||

| Low (<$30,000) | 138 (11.72) | 76 (13.74) |

| Medium ($30,000 to <$60,000) | 188 (15.97) | 85 (15.37) |

| High (≥$60,000) | 713 (60.58) | 341 (61.66) |

| Unknown (DK, PNS, Missing) | 138 (11.72) | 51 (9.22) |

| Alcohol Use * | ||

| Low risk volume ≤ 10 for females/15 for males per week | 866 (73.58) | 402 (72.69) |

| Risky volume 11–19/16–29 per week | 74 (6.29) | 44 (7.96) |

| High risk volume ≥ 20/30 per week | 114 (9.69) | 70 (12.66) |

| Unknown (DK, PNS, Missing) | 123 (10.45) | 37 (6.69) |

| Health Literacy Levels ** | ||

| Limited literacy (score ≤ 1) | 364 (30.93) | 129 (23.33) |

| Possibility of limited literacy (score 2–3) | 210 (17.84) | 123 (22.24) |

| Adequate literacy (score 4–6) | 527 (44.7) | 266 (48.10) |

| Unknown (DK, PNS, Missing) | 76 (6.46) | 35 (6.33) |

| Variable | Availability (N = 1680) | Pricing (N = 1681) | Marketing (N = 1677) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N (%) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) 1 | N | N (%) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) 1 | N | N (%) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) 1 | |

| Knowledge of alcohol as a carcinogen | |||||||||

| Not caused by alcohol | 1055 | 278 (26.35) | 1.00 (ref) | 1056 | 277 (26.23) | 1.00 (ref) | 1056 | 767 (72.63) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Caused by alcohol | 625 | 232 (37.12) | 1.62 (1.30, 2.01) | 625 | 254 (40.64) | 1.87 (1.51, 2.32) | 621 | 499 (80.35) | 1.44 (1.12, 1.99) |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 847 | 229 (27.04) | 1.00 (ref) | 847 | 254 (29.99) | 1.00 (ref) | 841 | 602 (71.58) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Female | 833 | 281 (33.73) | 1.31 (1.06, 1.63) | 834 | 277 (33.21) | 1.09 (0.88, 1.35) | 836 | 664 (79.43) | 1.51 (1.20, 1.92) |

| Age | |||||||||

| 19–24 | 128 | 24 (18.75) | 1.00 (ref) | 127 | 30 (23.62) | 1.00 (ref) | 127 | 72 (56.69) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 25–44 | 676 | 192 (28.40) | 1.61 (0.99, 2.62) | 675 | 223 (33.04) | 1.43 (0.91, 2.25) | 676 | 497 (73.52) | 1.80 (1.19, 2.71) |

| 45+ | 876 | 294 (33.56) | 2.06 (1.27, 3.33) | 879 | 278 (31.63) | 1.38 (0.88, 2.17) | 874 | 697 (79.75) | 2.41 (1.60, 3.63) |

| Education Level | |||||||||

| Low | 317 | 93 (29.34) | 1.00 (ref) | 319 | 83 (26.02) | 1.00 (ref) | 320 | 205 (64.06) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Medium | 585 | 151 (25.81) | 0.80 (0.58, 1.10) | 584 | 157 (26.88) | 1.03 (0.74, 1.43) | 583 | 424 (72.73) | 1.15 (0.84,1.57) |

| High | 705 | 244 (34.61) | 0.94 (0.66, 1.34) | 704 | 271 (38.49) | 1.59 (1.15, 2.20) | 704 | 593 (84.23) | 1.84 (1.30, 2.59) |

| Unknown | 73 | 22 (30.14) | 0.96 (0.54, 1.72) | 74 | 20 (27.03) | 0.97 (0.54, 1.75) | 70 | 44 (62.86) | 1.11 (0.63, 1.96) |

| Alcohol Use | |||||||||

| Low Risk volume | 1234 | 381 (30.88) | 1.00 (ref) | 1234 | 409 (33.14) | 1.00 (ref) | 1232 | 969 (78.65) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Risky volume | 126 | 34 (26.98) | 0.82 (0.54, 1.26) | 126 | 27 (21.43) | 0.55 (0.35, 0.86) | 125 | 95 (76.00) | 0.97 (0.62,1.53) |

| High Risk volume | 186 | 53 (28.49) | 0.94 (0.66, 1.34) | 186 | 58 (31.18) | 0.97 (0.69, 1.38) | 184 | 124 (67.39) | 0.74 (0.52,1.06) |

| Unknown | 134 | 42 (31.34) | 1.11 (0.73, 1.69) | 135 | 37 (27.41) | 0.91 (0.60, 1.40) | 136 | 78 (57.35) | 0.55 (0.37, 0.82) |

| Site | |||||||||

| Comparison | 643 | 162 (25.19) | 1.00 (ref) | 642 | 197 (30.69) | 1.00 (ref) | 641 | 451 (70.36) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Intervention | 1037 | 348 (33.56) | 1.36 (1.08,1.72) | 1039 | 334 (32.15) | 1.02 (0.82,1.28) | 1036 | 815 (78.67) | 1.26 (0.99, 1.60) |

| Wave | |||||||||

| 2 | 512 | 140 (27.34) | 1.00 (ref) | 517 | 155 (29.98) | 1.00 (ref) | 510 | 350 (68.63) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 3 | 1168 | 370 (31.68) | 1.07 (0.84, 1.36) | 1164 | 376 (32.30) | 0.96 (0.75, 1.21) | 1167 | 916 (78.49) | 1.25 (0.97, 1.60) |

| Increase in Knowledge | Availability (N = 433 1) | Pricing (N = 431 1) | Marketing (N= 430 1) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N (%) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) 2 | N | N (%) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) 2 | N | N (%) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) 2 | |

| No | 345 | 87 (25.22) | 1.00 (ref) | 344 | 91 (26.45) | 1.00 (ref) | 343 | 260 (75.80) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Yes | 88 | 24 (27.27) | 1.15 (0.66, 1.99) | 87 | 34 (39.08) | 1.86 (1.11, 3.12) | 87 | 71 (81.61) | 1.40 (0.73, 2.71) |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Weerasinghe, A.; Schoueri-Mychasiw, N.; Vallance, K.; Stockwell, T.; Hammond, D.; McGavock, J.; Greenfield, T.K.; Paradis, C.; Hobin, E. Improving Knowledge that Alcohol Can Cause Cancer is Associated with Consumer Support for Alcohol Policies: Findings from a Real-World Alcohol Labelling Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 398. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020398

Weerasinghe A, Schoueri-Mychasiw N, Vallance K, Stockwell T, Hammond D, McGavock J, Greenfield TK, Paradis C, Hobin E. Improving Knowledge that Alcohol Can Cause Cancer is Associated with Consumer Support for Alcohol Policies: Findings from a Real-World Alcohol Labelling Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(2):398. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020398

Chicago/Turabian StyleWeerasinghe, Ashini, Nour Schoueri-Mychasiw, Kate Vallance, Tim Stockwell, David Hammond, Jonathan McGavock, Thomas K. Greenfield, Catherine Paradis, and Erin Hobin. 2020. "Improving Knowledge that Alcohol Can Cause Cancer is Associated with Consumer Support for Alcohol Policies: Findings from a Real-World Alcohol Labelling Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 2: 398. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020398

APA StyleWeerasinghe, A., Schoueri-Mychasiw, N., Vallance, K., Stockwell, T., Hammond, D., McGavock, J., Greenfield, T. K., Paradis, C., & Hobin, E. (2020). Improving Knowledge that Alcohol Can Cause Cancer is Associated with Consumer Support for Alcohol Policies: Findings from a Real-World Alcohol Labelling Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(2), 398. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020398