Perceived Determinants of Children’s Inadequate Sleep Health. A Concept Mapping Study among Professionals

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

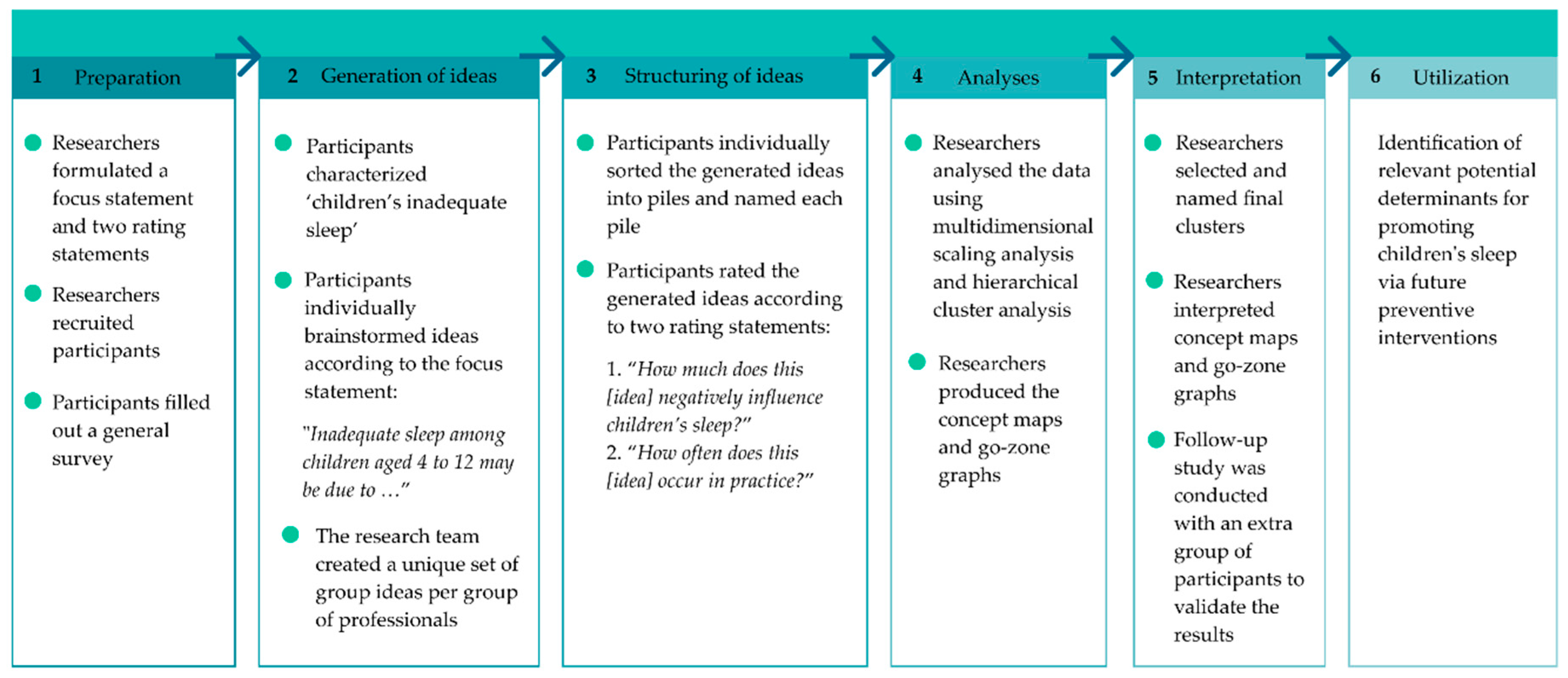

2.1. Step (1) Preparation

2.2. Step (2) Generating Ideas

2.3. Step (3) Structuring Ideas

2.4. Step (4) Analyses

2.5. Step (5) Interpretation

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Concept Maps

3.3. Perceived Determinants of Children’s Inadequate Sleep

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Buysse, D.J. Sleep health: Can we define it? Does it matter? Sleep 2014, 37, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, L.; Bin, Y.S.; Lallukka, T.; Kronholm, E.; Dumuid, D.; Paquet, C.; Olds, T. Past, present, and future: Trends in sleep duration and implications for public health. Sleep Health 2017, 3, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, G.K.; Kenney, M.K. Rising prevalence and neighborhood, social, and behavioral determinants of sleep problems in US children and adolescents, 2003–2012. Sleep Disord. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Litsenburg, R.R.; Waumans, R.C.; van den Berg, G.; Gemke, R.J. Sleep habits and sleep disturbances in Dutch children: A population-based study. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2010, 169, 1009–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaput, J.P.; Gray, C.E.; Poitras, V.J.; Carson, V.; Gruber, R.; Olds, T.; Weiss, S.K.; Connor Gorber, S.; Kho, M.E.; Sampson, M.; et al. Systematic review of the relationships between sleep duration and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 41, S266–S282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maski, K.P.; Kothare, S.V. Sleep deprivation and neurobehavioral functioning in children. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2013, 89, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeh, A.; Tikotzky, L.; Kahn, M. Sleep in infancy and childhood: Implications for emotional and behavioral difficulties in adolescence and beyond. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2014, 27, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astill, R.G.; Van der Heijden, K.B.; Van Ijzendoorn, M.H.; Van Someren, E.J. Sleep, cognition, and behavioral problems in school-age children: A century of research meta-analyzed. Psychol. Bull. 2012, 138, 1109–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewald, J.F.; Meijer, A.M.; Oort, F.J.; Kerkhof, G.A.; Bogels, S.M. The influence of sleep quality, sleep duration and sleepiness on school performance in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Sleep Med. Rev. 2010, 14, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, Y.; Doi, S.A.; Mamun, A.A. Longitudinal impact of sleep on overweight and obesity in children and adolescents: A systematic review and bias-adjusted meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2015, 16, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.A.; Kruisbrink, M.; Wallace, J.; Ji, C.; Cappuccio, F.P. Sleep duration and incidence of obesity in infants, children, and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep 2018, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, L.S.; Danielsen, K.V.; Sorensen, T.I. Short sleep duration as a possible cause of obesity: Critical analysis of the epidemiological evidence. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartholomew Eldredge, L.; Markham, C.M.; Ruiter, R.A.; Fernández, M.E.; Kok, G.; Parcel, G.S. Planning Health Promotion Programs: An Intervention Mapping Approach, 4th ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Belmon, L.S.; van Stralen, M.M.; Busch, V.; Harmsen, I.A.; Chinapaw, M.J. What are the determinants of children’s sleep behavior? A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Sleep Med. Rev. 2019, 43, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, S.L.; Howlett, M.D.; Coulombe, J.A.; Corkum, P.V. ABCs of SLEEPING: A review of the evidence behind pediatric sleep practice recommendations. Sleep Med. Rev. 2016, 29, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belmon, L.S.; Busch, V.; van Stralen, M.M.; Stijnman, D.P.; Hidding, L.M.; Harmsen, I.A.; Chinapaw, M.J. Child and Parent Perceived Determinants of Children’s Inadequate Sleep Health. A Concept Mapping Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, M.T.; Trochim, W.M.K. Concept Mapping for Planning and Evaluation, 1st ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007; Volume 50. [Google Scholar]

- Trochim, W.M.K.; McLinden, D. Introduction to a special issue on concept mapping. Eval. Program Plan. 2017, 60, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidding, L.M.; Altenburg, T.M.; van Ekris, E.; Chinapaw, M.J.M. Why Do Children Engage in Sedentary Behavior? Child- and Parent-Perceived Determinants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidding, L.M.; Chinapaw, M.J.M.; Altenburg, T.M. An activity-friendly environment from the adolescent perspective: A concept mapping study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariadne. Available online: http://www.minds21.org/ (accessed on 20 November 2019).

- IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2016.

- Microsoft Corporation. Microsoft Excel. 2016. Available online: https://office.microsoft.com/excel (accessed on 29 September 2020).

- Hale, L.; Guan, S. Screen time and sleep among school-aged children and adolescents: A systematic literature review. Sleep Med. Rev. 2015, 21, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernikova, M.; Smahel, D.; Wright, M.F. Children’s experiences and awareness about impact of digital media on health. Health Commun. 2018, 33, 664–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hale, L.; Kirschen, G.W.; LeBourgeois, M.K.; Gradisar, M.; Garrison, M.M.; Montgomery-Downs, H.; Kirschen, H.; McHale, S.M.; Chang, A.-M.; Buxton, O.M. Youth screen media habits and sleep: Sleep-friendly screen behavior recommendations for clinicians, educators, and parents. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. 2018, 27, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauricella, A.R.; Wartella, E.; Rideout, V.J. Young children’s screen time: The complex role of parent and child factors. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2015, 36, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.B.; Bednarz, J.M.; Aromataris, E.C. Interventions to control children’s screen use and their effect on sleep: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Sleep Res. 2020, e13130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, S.A.; Fulton, J.E.; Lee, S.M.; Foley, J.T.; Heitzler, C.; Huhman, M. Influence of limit-setting and participation in physical activity on youth screen time. Pediatrics 2010, 126, e89–e96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafson, S.L.; Rhodes, R.E. Parental Correlates of Physical Activity in Children and Early Adolescents. Sports Med. 2006, 36, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galland, B.C.; Mitchell, E.A. Helping children sleep. Arch. Dis. Child. 2010, 95, 850–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolezal, B.A.; Neufeld, E.V.; Boland, D.M.; Martin, J.L.; Cooper, C.B. Interrelationship between sleep and exercise: A systematic review. Adv. Prev. Med. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikotzky, L. Parenting and sleep in early childhood. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2017, 15, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, L.K.; Parcel, G.S.; Kok, G.; Gottlieb, N.H.; Schaalma, H.C.; Markham, C.C.; Tyrrell, S.C.; Shegog, R.C.; Fernández, M.C.; Mullen, P.D.C. Planning Health Promotion Programs: An Intervention Mapping Approach; Jossey-Bass: San Fransico, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kok, G.; Gottlieb, N.H.; Commers, M.; Smerecnik, C. The ecological approach in health promotion programs: A decade later. Am. J. Health Promot. AJHP 2008, 22, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovmand, P.S. Introduction to Community-Based System Dynamics. In Community Based System Dynamics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.; Hummelbrunner, R. Systems Concepts in Action: A Practitioner’s Toolkit; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, R.D.; Wade, J.P. A Definition of Systems Thinking: A Systems Approach. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 44, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, V.; Altenburg, T.M.; Harmsen, I.A.; Chinapaw, M.J. Interventions that stimulate healthy sleep in school-aged children: A systematic literature review. Eur. J. Public Health 2017, 27, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Original Study Sample | Validation Study Sample | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doctors (N = 9) | Nurses (N = 11) | Sleep Experts (N = 7) | Mixed Group of Professionals (N = 16) | |

| Age (years, M, SD) | 40.3 (8.3) | 48.1 (13.0) | 45.1 (11.6) | 43.7 (9.9) |

| Female (%) | 88.9 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 93.8 |

| Working experience (years, M, SD) | 10.6 (6.3) | 13.3 (10.8) | 15.7 (12.1) | 5.3 (3.6) |

| Share of sleep in their work (%) | ||||

| Large | 33.3 | 18.2 | 100.0 | 50.0 |

| Moderate | 55.6 | 54.5 | 0.0 | 37.5 |

| Small | 11.1 | 27.3 | 0.0 | 12.5 |

| Category | Perceived Determinants | Examples of Underlying Original Ideas | Mean Rating per Professionals’ Group | Mean Rating 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doctors | Nurses | Sleep Experts | ||||||||

| In | Oc | In | Oc | In | Oc | In | Oc | |||

| Psychosocial determinants | 3.7 | 2.7 | ||||||||

| Being bullied | “Being bullied and worrying about this in the evening/at night” | N.A. | N.A. | 4.3 | 2.8 | 4.3 | 2.7 | 4.3 | 2.8 | |

| A change in daily life | “Changes in the home situation: divorce, death of a loved one”, “Changes in daily life: moving, new school, holidays” | 3.6 | 3.2 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 4.3 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 3.1 | |

| Worrying | “Worrying about the day that has been”, “Worrying in the evening/at night about problems at school” | 3.7 | 2.9 | 4.0 | 2.8 | 4.0 | 3.4 | 3.9 | 3.0 | |

| Stressful family situation | “Experiencing stress due to arguing at home” | 4.3 | 2.5 | 4.3 | 2.9 | 4.0 | 2.7 | 4.2 | 2.7 | |

| Traumatic event | “A traumatic experience from the past” | 4.1 | 2.2 | 4.3 | 2.7 | 3.9 | 2.6 | 4.1 | 2.5 | |

| Upcoming stressful event | “Feeling stressed about something that will happen the next day” | N.A. | N.A. | 3.6 | 2.8 | N.A. | N.A. | 3.6 | 2.8 | |

| Unprocessed thoughts or feelings | “Having to process the day” | 3.3 | 2.8 | 3.5 | 3.0 | N.A. | N.A. | 3.4 | 2.9 | |

| Bedtime resistance 4 | “Refusing to go to bed” | N.A. | N.A. | 3.3 | 2.6 | 3.9 | 2.9 | 3.6 | 2.7 | |

| Nightmares | “Scary or bad dreams that wake a child” | 3.6 | 2.8 | 3.6 | 2.6 | 3.6 | 2.7 | 3.6 | 2.7 | |

| Performance pressure | “Feeling pressure to perform well” | N.A. | N.A. | 3.5 | 2.8 | N.A. | N.A. | 3.5 | 2.8 | |

| Feeling unsafe | “Not feeling safe at home or at school” | 3.8 | 2.1 | 4.2 | 2.3 | 4.0 | 2.3 | 4.0 | 2.2 | |

| Fear | “Scared of parent(s) leaving”, “Fear of the dark” | 3.5 | 2.2 | 3.8 | 2.9 | 3.7 | 2.3 | 3.6 | 2.5 | |

| Loneliness | “Missing a parent or waiting for a parent to come home” | N.A. | N.A. | 3.5 | 2.5 | N.A. | N.A. | 3.5 | 2.5 | |

| Parental stress | “Parental stress and agitation that is transferred to the child” | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | 3.3 | 2.6 | 3.3 | 2.6 | |

| Child’s temperament | “The child’s temperament” | N.A. | N.A. | 2.6 | 3.1 | N.A. | N.A. | 2.6 | 3.1 | |

| Negative self-image 5 | “Negative self-image” | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Parents’ resilience 5 | “Parents’ support system”, “Parents’ mental health” | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Lack of attention from parent(s) 5 | “Need for undivided attention from parents” | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Daytime and evening activities 6 | 3.3 | 3.0 | ||||||||

| Screens in the bedroom | “Free use of screens (TV, phone, tablet, computer) in the bedroom” | N.A. | N.A. | 4.5 | 3.4 | N.A. | N.A. | 4.5 | 3.4 | |

| Screen use before bedtime | “Screen use (TV, phone, tablet, computer) right before sleeping”, “Watching a movie until late before going to sleep” | 4.1 | 4.0 | 3.9 | 3.4 | 4.1 | 3.9 | 4.0 | 3.7 | |

| Playing stimulating games before bedtime | “Gaming/Playing on the game console until right before going to sleep” or “Too busy with playing around just before going to bed” | 3.9 | 3.8 | 3.4 | 2.6 | 4.4 | 3.7 | 3.9 | 3.4 | |

| Excessive daytime screen use | “Excessive use of computer or other screens (tablet, phone) during the day”, “Excessive gaming/playing on the game console during the day” | N.A. | N.A. | 3.4 | 3.8 | 2.9 | 3.6 | 3.1 | 3.7 | |

| Inadequate time to relax | “Not relaxing enough before going to bed, causing the brain to be too active”, “Doing homework until late in the evening” | N.A. | N.A. | 3.3 | 3.5 | 3.9 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 3.5 | |

| Inadequate amount of daytime PA | “A lack of exercise during the day” | 2.9 | 3.2 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 3.2 | |

| Sleep-disrupting food or drinks | “Drinking stimulating (sugary and/or caffeinated) drinks in the evening” | 3.8 | 2.4 | N.A. | N.A. | 3.4 | 3.0 | 3.6 | 2.7 | |

| Too much evening light | “Too much light in the evening” | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | 3.4 | 2.9 | 3.4 | 2.9 | |

| Bed also used for other activities | “Using the bed for more than just sleeping: playing in bed, watching TV in bed” | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | 2.7 | 3.4 | 2.7 | 3.4 | |

| Inadequate time outside at daytime | “Too little light and fresh air during the day due to being inside too much” | 2.9 | 3.1 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 3.1 | 3.3 | 2.9 | 3.1 | |

| Inadequate morning light | “Too little light in the morning” | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | 3.1 | 2.7 | 3.1 | 2.7 | |

| Evening PA | “Being physically active/doing sports late in the evening” | 3.2 | 2.0 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 3.9 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 2.4 | |

| Too many daytime activities | “Too many daytime activities” | N.A. | N.A. | 3.0 | 2.4 | N.A. | N.A. | 3.0 | 2.4 | |

| Eating/drinking close to bedtime | “Eating/drinking too late” | 2.8 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 3.0 | 2.4 | 2.7 | 2.4 | |

| Medical determinants | 3.6 | 2.5 | ||||||||

| Disturbed biological clock | “A disturbed biological clock” | N.A. | N.A. | 4.0 | 2.5 | 4.4 | 3.9 | 4.2 | 3.2 | |

| Illness | “Illness/pain” | 3.1 | 3.0 | 3.7 | 2.1 | 4.3 | 2.9 | 3.7 | 2.7 | |

| Mental problems | “Mental condition” | 3.3 | 2.2 | 3.6 | 2.4 | 4.0 | 3.4 | 3.7 | 2.7 | |

| Medication use with effects on sleep | “Using melatonin (sleeping pills) wrongly” | 3.6 | 2.1 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 3.9 | 3.1 | 3.8 | 2.4 | |

| Sleep disorder | “Wetting the bed”, “Sleep walking” | 3.9 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 2.0 | 4.5 | 3.4 | 3.7 | 2.6 | |

| Physical complaint | “Cold feet”, “Growing pain in the legs | 4.3 | 2.6 | N.A. | N.A. | 3.6 | 1.9 | 4.0 | 2.2 | |

| Medical complaint | “Overweight/obesity”, “Allergy/itch | 3.0 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 3.9 | 2.2 | 3.2 | 2.5 | |

| Heredity for sleep problems | “Heredity for sleep problems/hereditary” | 2.8 | 1.8 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | 2.8 | 1.8 | |

| High sensitivity 5 | “High sensitivity” | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Pedagogical determinants | 3.2 | 2.8 | ||||||||

| No consistent sleep schedule | “Having irregular sleep times”, “Going to bed too late/Being put to bed too late” | 3.7 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.7 | 4.0 | 3.6 | 3.7 | 3.5 | |

| Inadequate structure of the day | “Having no rhythm and little structure in the daily routine” | 3.9 | 3.11 | 3.5 | 3.4 | N.A. | N.A. | 3.7 | 3.3 | |

| Parents’ inability to set boundaries | “Parents who find it difficult to set limits” | 3.4 | 3.3 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | 3.4 | 3.3 | |

| No bedtime routine | “Having no set sleep/bedtime routine” | 3.4 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.1 | 3.6 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.2 | |

| Lack of clear rules | “Parents who do not set clear rules or are too strict” | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.3 | |

| Daytime nap | “Sleeping (too much) at daytime” | 3.4 | 2.4 | 3.9 | 2.4 | 4.0 | 2.3 | 3.8 | 2.4 | |

| Inadequate bedtime 7 | “Going to bed too early or being put to bed too early” | 2.9 | 1.9 | N.A. | N.A. | 3.9 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 2.6 | |

| Parents’ negative focus on sleep | “Parents who create negative attention around sleep by putting too much emphasis on having to sleep” | N.A. | N.A. | 3.4 | 2.5 | 3.4 | 2.6 | 3.4 | 2.5 | |

| Parents each applying different bedtime rules | “(Separated) parents applying different rules regarding bedtimes” | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | 3.3 | 2.4 | 3.3 | 2.4 | |

| Co-sleeping | “Sleeping in bed with parents or other family member” | 3.0 | 2.8 | 2.1 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 3.4 | 2.7 | 3.0 | |

| Bedtime procrastination | “Children demand a too elaborate bedtime ritual before going to sleep” | 3.1 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 3.7 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 2.6 | |

| Insufficient parental sleep-related knowledge | “Uncertainty among parents about what an appropriate bedtime is” | N.A. | N.A. | 2.1 | 2.8 | N.A. | N.A. | 2.1 | 2.8 | |

| Social norm for bedtime at school | “Comparing oneself to classmates who go to bed later” | N.A. | N.A. | 2.2 | 2.7 | N.A. | N.A. | 2.2 | 2.7 | |

| Inadequate amount of food or drink | “Being hungry or thirsty” | N.A. | N.A. | 2.7 | 2.0 | N.A. | N.A. | 2.7 | 2.0 | |

| No time to put child to bed 5 | “Parents do not put their child to bed on time because they prioritise other matters, e.g., work, being home late, cleaning” | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Parents set the wrong example 5 | “Setting the wrong example regarding screen use” | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Social norm for playing outside 5 | “The norms for playing outside” | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Parents’ ability to respond to the child’s sleep problems 5 | “Knowledge, ability, and skills to react adequately to night terrors, trouble falling asleep, or sleeping through the night” | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Parents’ attitude towards sleep 5 | “Parents’ thoughts on sleep” | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Sleep-environmental determinants | 2.8 | 2.1 | ||||||||

| No bedroom | “Not having a bedroom or sleeping in another place in the house” | 3.1 | 2.7 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | 3.1 | 2.7 | |

| Bedroom sharing | “Sleeping with multiple people in a room” | 2.7 | 3.1 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 3.7 | 2.0 | 3.1 | 2.7 | |

| Noise outside | “Noise in the neighbourhood/outside” | 3.1 | 2.1 | 3.1 | 2.5 | 3.0 | 1.9 | 3.1 | 2.2 | |

| Cramped housing | “Living in a small house with a lot of people” | N.A. | N.A. | 2.6 | 2.5 | N.A. | N.A. | 2.6 | 2.5 | |

| Noise inside | “Noise in the house” | N.A. | N.A. | 2.7 | 2.3 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 2.9 | 2.2 | |

| Uncomfortable bed | “Uncomfortable bed” | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | 3.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | |

| Too much light | “Not dark enough in the bedroom” | 2.6 | 1.8 | 2.7 | 1.6 | 3.0 | 2.4 | 2.8 | 2.0 | |

| Not the right temperature | “Too cold or too warm in the bedroom” | 3.0 | 2.0 | 2.8 | 1.7 | 2.7 | 1.9 | 2.8 | 1.9 | |

| Not ventilated | “Room not ventilated” | 2.7 | 1.9 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | 2.7 | 1.9 | |

| Untidy bedroom | “Too much clutter or stuffed pets in the room” | N.A. | N.A. | 1.9 | 1.4 | 2.9 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 1.9 | |

| Uncomfortable sleep wear | “Uncomfortable sleep wear” | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | 2.6 | 1.1 | 2.6 | 1.1 | |

| Absence of stuffed toy 5 | “Safety through stuffed toy” | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Belmon, L.S.; Brasser, F.B.; Busch, V.; van Stralen, M.M.; Harmsen, I.A.; Chinapaw, M.J.M. Perceived Determinants of Children’s Inadequate Sleep Health. A Concept Mapping Study among Professionals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7315. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197315

Belmon LS, Brasser FB, Busch V, van Stralen MM, Harmsen IA, Chinapaw MJM. Perceived Determinants of Children’s Inadequate Sleep Health. A Concept Mapping Study among Professionals. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(19):7315. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197315

Chicago/Turabian StyleBelmon, Laura S., Fay B. Brasser, Vincent Busch, Maartje M. van Stralen, Irene A. Harmsen, and Mai J. M. Chinapaw. 2020. "Perceived Determinants of Children’s Inadequate Sleep Health. A Concept Mapping Study among Professionals" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 19: 7315. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197315

APA StyleBelmon, L. S., Brasser, F. B., Busch, V., van Stralen, M. M., Harmsen, I. A., & Chinapaw, M. J. M. (2020). Perceived Determinants of Children’s Inadequate Sleep Health. A Concept Mapping Study among Professionals. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(19), 7315. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197315