What Makes Hotel Chefs in Korea Interact with SNS Community at Work? Modeling the Interplay between Social Capital and Job Satisfaction by the Level of Customer Orientation

Abstract

1. Introduction

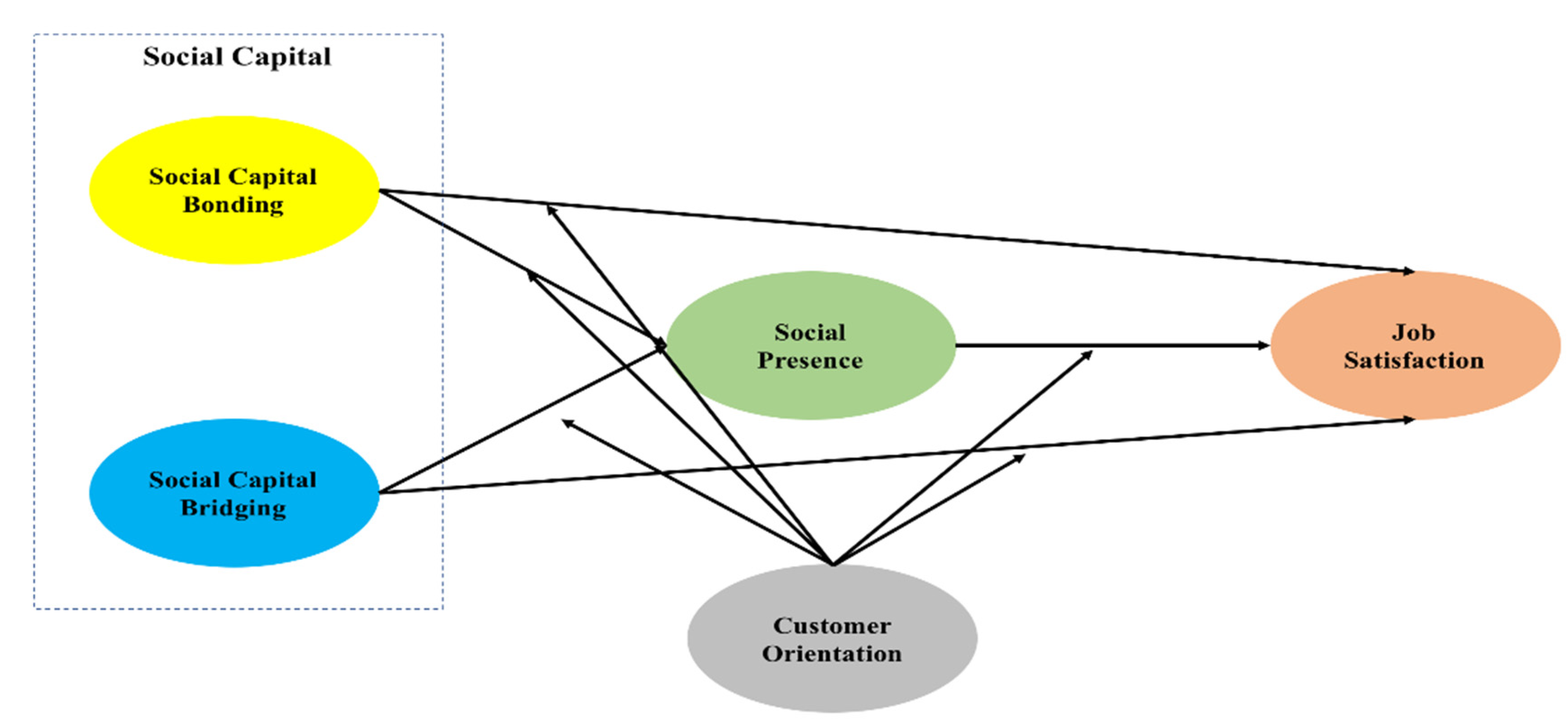

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Factors Affecting Chef Job Satisfaction

2.2. Chef SNS Community Participation

2.3. Social Capital and Social Presence

2.4. Social Presence and Job Satisfaction

2.5. Social Capital and Job Satisfaction

2.6. Moderating Effect of Customer Orientation

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Study Design and Participants

3.2. Measures

3.3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

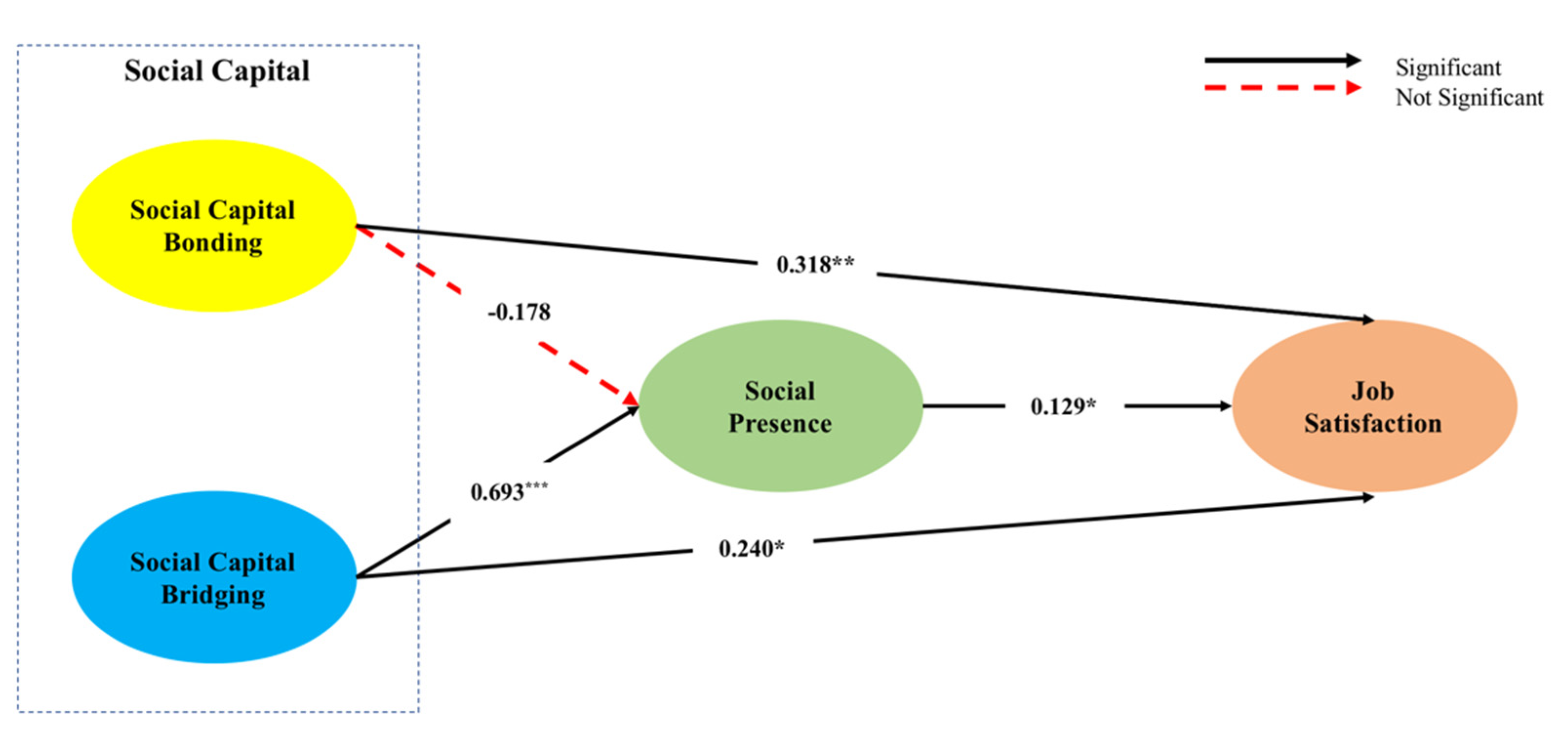

4.2. Structural Model and Discussion

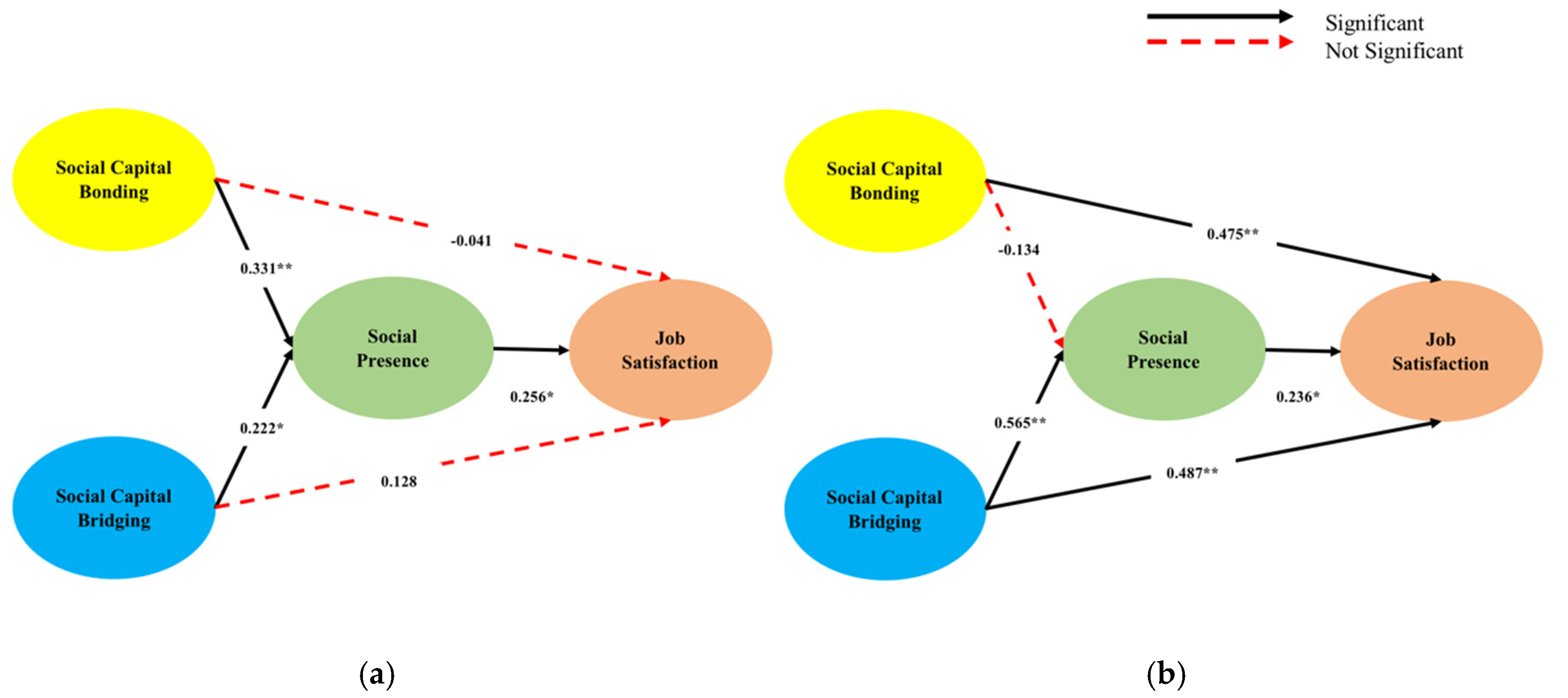

4.3. Moderation Effect

4.4. Mediation Effect

5. Conclusions

6. Implications

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Managerial Implications

6.3. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ko, W.H. The relationships among professional competence, job satisfaction and career development confidence for chefs in Taiwan. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 1004–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Thoresen, C.J.; Bono, J.E.; Patton, G.K. The job satisfaction-job performance relationship: A qualitative and quantitative review. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 127, 376–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayton, B.A. Examining the interconnection of job satisfaction and organizational commitment: An application of the bivariate probit model. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2006, 17, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkutlu, H. The impact of transformational leadership on organizational and leadership effectiveness. J. Manag. Dev. 2008, 27, 708–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Sin, R.C.S. Drivers of job satisfaction as related to work performance in Macao casino hotels. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 21, 561–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, G.; Purcell, K. As cooks go, she went: Is labour churn inevitable? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2001, 20, 163–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, N.K.; Yin, D.; Dellmann-Jenkins, M. Intrinsic and extrinsic factors impacting casino hotel chefs’ job satisfaction. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 21, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongchaiprasit, P.; Ariyabuddhiphongs, V. Creativity and turnover intention among hotel chefs: The mediating effects of job satisfaction and job stress. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 55, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.; Cheung, C.; Song, H. Hotel career management in China: Developing a measure scale. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, B.R.; Bradley, L. The impact of organizational support for career development on career satisfaction. Career Dev. Int. 2007, 12, 40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Duggan, M. Mobile Messaging and Social Media 2015; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Phua, J.; Jin, S.V.; Kim, J.J. Uses and gratifications of social networking sites for bridging and bonding social capital: A comparison of Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 72, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, G.; Chung, H. Applying the technology acceptance model to social networking sites (SNS): Impact of subjective norm and social capital on the acceptance of SNS. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2013, 29, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubke, F. Creative hot spots: A network analysis of German Michelin-starred chefs. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2014, 23, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali-Hassan, H.; Nevo, D.; Wade, M. Linking dimensions of social media use to job performance: The role of social capital. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2015, 24, 65–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.I.; Lee, E. The effect of social capital on job satisfaction and quality of care among hospital nurses in South Korea. J. Nurs. Manag. 2016, 24, 934–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, C.; Ommen, O.; Driller, E.; Ernstmann, N.; Wirtz, M.A.; Köhler, T.; Pfaff, H. Burnout in nurses—The relationship between social capital in hospitals and emotional exhaustion. J. Clin. Nurs. 2010, 19, 1654–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuang, N.-K.; Lei, S.A. Job stress among casino hotel chefs in a top-tiertourism city. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2011, 20, 551–574. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, J.C.; Yi, O. Hotel employee job crafting, burnout, and satisfaction: The moderating role of perceived organizational support. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 72, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norbu, J.; Wetprasit, P. The Study of Job Motivational Factors and Its Influence on Job Satisfaction for Hotel Employees of Thimphu, Bhutan. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2020, 1, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, L.M. How customer orientation leads to customer satisfaction. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2019, 37, 210–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenzi, P.; De Luca, L.M.; Troilo, G. Organizational drivers of salespeople’s customer orientation and selling orientation. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2011, 31, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.; George, R.T. Understanding the influence of polychronicity on job satisfaction and turnover intention: A study of non-supervisory hotel employees. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mount, D.J.; Bartlett, A.L. Development of a job satisfaction factor model for the lodging industry. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2002, 1, 17–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, B.; Jacob, M. Knowledge sharing intentions among IT professionals in India. Commun. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2011, 114, 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Noe, R.A. Knowledge sharing: A review and directions for future research. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2010, 20, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwis, R.S.; Hartmann, E. The use of tacit knowledge within innovative companies: Knowledge management in innovative enterprises. J. Knowl. Manag. 2008, 12, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.-K.; Lu, L.-C.; Liu, T.-F. Exploring factors that influence knowledge sharing behavior via weblogs. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferneley, E.; Helms, R. Editorial. J. Inf. Technol. 2010, 25, 107–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leftheriotis, I.; Giannakos, M.N. Using social media for work: Losing your time or improving your work? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeussler, C. Information-sharing in academia and the industry: A comparative study. Res. Policy 2011, 40, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D. On and off the ’net: Scales for social capital in an online era. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2006, 11, 593–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, N.B.; Vitak, J.; Gray, R.; Lampe, C. Cultivating social resources on social network sites: Facebook relationship maintenance behaviors and their role in social capital processes. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2014, 19, 855–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.V.; Liu, P.L. Ties that work: Investigating the relationships among coworker connections, work-related Facebook utility, online social capital, and employee outcomes. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 72, 512–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oztok, M.; Zingaro, D.; Makos, A.; Brett, C.; Hewitt, J. Capitalizing on social presence: The relationship between social capital and social presence. Internet High. Educ. 2015, 26, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.H. Defining sociability and social presence in Social TV. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 939–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.T.; Chiang, Y.H. Bridging social capital matters to Social TV viewing: Investigating the impact of social constructs on program loyalty. Telemat. Inform. 2019, 43, 101236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, J.; Williams, E.; Christie, B. The Social Psychology of Telecommunications; John Wiley & Sons: London, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Reio, T.G., Jr.; Crim, S.J. Social presence and student satisfaction as predictors of online enrollment intent. Am. J. Distance Educ. 2013, 27, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyle, M.; Dean, J. Eye-contact, distance and affiliation. Sociometry 1965, 28, 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiner, M.; Mehrabian, A. Language within Language: Immediacy, a Channel in Verbal Communication; Appleton: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, J.; Swan, K. Examing social presence in online courses in relation to students’ perceived learning and satisfaction. JALN 2003, 7, 68–88. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, R. Using Communicaitons Media in Open and Flexible Learning; Kogan Page: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, K.; Biocca, F. Understanding the influence of agency and anthropomorphism on copresence, social presence and physical presence with virtual humans. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 2001, 12, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinout, E.D.V.; Hooff, B.V.D.; Ridder, J.A.D. Explaining knowledge sharing: The role of team communication styles, job satisfaction, and performance beliefs. Commun. Res. 2006, 33, 115–135. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison, N.B.; Steinfield, C.; Lampe, C. The benefits of Facebook “friends:” Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2007, 12, 1143–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonner, K.L.; Roloff, M.E. Testing the connectivity paradox: Linking teleworkers’ communication media use to social presence, stress from interruptions, and organizational identification. Commun. Monogr. 2012, 79, 205–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas-Machuca, M.; Berbegal-Mirabent, J.; Alegre, I. Work-life balance and its relationship with organizational pride and job satisfaction. J. Manag. Psychol. 2016, 31, 586–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Siu, O.; Cheung, F. A study of work–family enrichment among Chinese employees: The mediating role between work support and job satisfaction. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 63, 130–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.G.; Shore, L.M.; Griffeth, R.W. The role of perceived organizational support and supportive human resource practices in the turnover process. J. Manag. 2003, 29, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fila, M.J.; Paik, L.S.; Griffeth, R.W.; Allen, D. Disaggregating job satisfaction: Effects of perceived demands, control, and support. J. Bus. Psychol. 2014, 29, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlo, O.; Bell, S.J.; Mengüç, B.; Whitwell, G.J. Social capital, customer service orientation and creativity in retail stores. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 1214–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Requena, F. Social capital, satisfaction and quality of life in the workplace. Soc. Indic. Res. 2003, 61, 331–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terho, H.; Eggert, A.; Haas, A.; Ulaga, W. How sales strategy translates into performance: The role of salesperson customer orientation and value-based selling. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2015, 45, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Griffith, D.A.; Liu, S.S.; Shi, Y.Z. The effects of customer relationships and social capital on firm performance: A Chinese business illustration. J. Int. Mark. 2004, 12, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eren, S.S.; Eren, M.Ş.; Ayas, N.; Hacioglu, G. The effect of service orientation on financial performance: The mediating role of job satisfaction and customer satisfaction. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 99, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.T.; Lee, G.; Paek, S.; Lee, S. Social capital, knowledge sharing and organizational performance. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 25, 683–704. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, P.S.; Kwon, S. Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Min, J.; Lee, H. Building relationships within corporate SNS accounts through social presence formation. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 945–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D. Managing user trust in B2C e-services. e-Service 2003, 2, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waschgler, K.; Ruiz-Hernández, J.A.; Llor-Esteban, B.; García-Izquierdo, M. Patients’ aggressive behaviours towards nurses: Development and psychometric properties of the hospital aggressive behaviour scale-users. J. Adv. Nurs. 2013, 69, 1418–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson Education Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, A.F.; Scharkow, M. The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis: Does method really matter? Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 1918–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Measurement | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Capital Bridging (SCBR) [57,58] | SCBR1: I use this SNS for cooking information because interacting with people whom I do not know in real life makes me interested in what people unlike me are thinking | 0.778 | 0.913 | 0.899 | 0.691 |

| SCBR2: I am willing to spend time on this SNS supporting the cooking information of people whom I do not know in real life | 0.873 | ||||

| SCBR3: I use this SNS for cooking information because interacting with people whom I do not know in real life makes me want to try new things | 0.866 | ||||

| SCBR4: I use this SNS for cooking information because interacting with people whom I do not know in real life makes me feel like part of a larger community | 0.885 | ||||

| Social Capital Bonding (SCBO) [46,57] | SCBO1: I use this SNS for cooking information because there is someone, whom I do not know in real life, who I can turn to for advice about making very important decisions | 0.818 | 0.910 | 0.903 | 0.652 |

| SCBO2: use this SNS for cooking information because the people whom I do not know in real life but with whom I interact with on this SNS would share their last dollar with me | 0.841 | ||||

| SCBO3: I use this SNS for cooking information because the people whom I do not know in real life but with whom I interact with on this SNS would put their reputations on the line for me | 0.774 | ||||

| SCBO4: I use this SNS for cooking information because the people whom I do not know in real life but with whom I interact with on this SNS would help me fight an injustice | 0.819 | ||||

| SCBO5: I use this SNS for cooking information because there are several people on this SNS whom I do not know in real life but who I trust to help solve my problems | 0.840 | ||||

| Social Presence (SP) [59,60] | SP1: There is a sense of human contact in SNS | 0.869 | 0.867 | 0.854 | 0.661 |

| SP2: There is a sense of personalness in SNS | 0.801 | ||||

| SP3: There is a sense of sociability in SNS | 0.813 | ||||

| Job Satisfaction (JS) [61] | JS1: How satisfied are you with your overall job? | 0.638 | 0.827 | 0.863 | 0.616 |

| JS2: How satisfied are you with your immediate supervisor? | 0.916 | ||||

| JS3: How satisfied are you with your organization’s policies? | 0.749 | ||||

| JS4: How satisfied are you with the support provided by your supervisor? | 0.680 | ||||

| Model fit: X2 = 267.845, GFI = 0.898, RMSEA = 0.08, RMR = 0.047, NFI = 0.913, and CFI = 0.942. |

| Construct | Descriptive Statistics | Discriminant Validity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | SCBO | SCBR | SP | JS | |

| SCBO | 2.84 | 0.98 | 1 | |||

| SCBR | 2.99 | 0.90 | 0.771 *** | 1 | ||

| SP | 3.12 | 0.94 | 0.383 *** | 0.491 *** | 1 | |

| JS | 3.34 | 0.73 | 0.208 *** | 0.123 * | 0.131 * | 1 |

| Hypothesis | Coefficient | Std. Error | T-Value | Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Bonding-Social Presence | −0.178 | 0.154 | −1.152 | No |

| H2: Bridging-Social Presence | 0.693 | 0.137 | 5.054 | Yes |

| H3: Social Presence-Job Satisfaction | 0.129 | 0.057 | 2.276 | Yes |

| H4: Bonding-Job Satisfaction | 0.318 | 0.116 | 2.739 | Yes |

| H5: Bridging-Job Satisfaction | 0.240 | 0.109 | 2.205 | Yes |

| Model Fitness: X2 = 267.845, GFI = 0.898, RMSEA = 0.08, RMR = 0.047, NFI = 0.913, CFI = 0.942. | ||||

| Default Model | X2 | DF | ΔX2 (df = 1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Free Model | 410.260 | 196 | |

| H1: Bonding-Social Presence | 414.621 | 197 | 4.361 |

| H2: Bridging-Social Presence | 412.858 | 197 | 2.598 |

| H3: Social Presence-Job Satisfaction | 410.271 | 197 | 0.011 |

| H4: Bonding-Job Satisfaction | 415.063 | 197 | 4.803 |

| H5: Bridging-Job Satisfaction | 412.781 | 197 | 2.521 |

| Path | High Customer Orientation | Low Customer Orientation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | T | p | Coefficient | T | p | |

| Bonding-Social Presence | −0.134 | −0.731 | 0.465 | 0.331 | 2.882 ** | 0.004 |

| Bridging-Social Presence | 0.565 | 3.028 ** | 0.002 | 0.222 | 1.969 * | 0.049 |

| Social Presence-Job Satisfaction | 0.236 | 1.982 * | 0.05 | 0.256 | 2.199 * | 0.028 |

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | Mediating Variable | Indirect Effect | Sobel Test | Confidence Interval 95% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLCI | ULCI | |||||

| Job Satisfaction | Social capital bonding | Social Presence | −0.041 | 2.211 * | −0.097 | −0.009 |

| Social capital bridging | −0.077 | 2.386 * | −0.155 | −0.020 | ||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seo, S.-W.; Kim, H.-C.; Zhu, Z.-Y.; Lee, J.-T. What Makes Hotel Chefs in Korea Interact with SNS Community at Work? Modeling the Interplay between Social Capital and Job Satisfaction by the Level of Customer Orientation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7129. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197129

Seo S-W, Kim H-C, Zhu Z-Y, Lee J-T. What Makes Hotel Chefs in Korea Interact with SNS Community at Work? Modeling the Interplay between Social Capital and Job Satisfaction by the Level of Customer Orientation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(19):7129. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197129

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeo, Sang-Won, Hyeon-Cheol Kim, Zong-Yi Zhu, and Jung-Tak Lee. 2020. "What Makes Hotel Chefs in Korea Interact with SNS Community at Work? Modeling the Interplay between Social Capital and Job Satisfaction by the Level of Customer Orientation" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 19: 7129. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197129

APA StyleSeo, S.-W., Kim, H.-C., Zhu, Z.-Y., & Lee, J.-T. (2020). What Makes Hotel Chefs in Korea Interact with SNS Community at Work? Modeling the Interplay between Social Capital and Job Satisfaction by the Level of Customer Orientation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(19), 7129. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197129