Implementation of the ‘Optimising the Health Extension Program’ Intervention in Ethiopia: A Process Evaluation Using Mixed Methods

Abstract

1. Background

2. Methods

2.1. Study Settings

2.2. Methods to Outline the Intervention Content

- -

- Consultative meetings: We held consultative meetings with project staff and asked them to describe in detail what was delivered, with what aim, how much, to whom, by whom, and what mode of delivery. Notes from the meetings were collated into a narrative description of the intervention, which was verified by the implementers.

- -

- Document review: We reviewed available program documents, including six implementation guidelines with training materials and procedure manuals. In addition, we reviewed four quarterly reports and over ten newsletters, to gather information about each intervention activity and its implementation plan. The documents we reviewed were in different formats, including hard copies and electronic documents. Some documents were in local languages, which were translated by the first author.

- -

- Field visits: We made field visits to three intervention PHCU sites out of a total of 149 and spent two days in each site, with the goal of understanding the intervention and the implementation process. We observed implementation and reviewed procedure manuals and intervention materials available at the site. We conducted informal interviews with five to ten people in each site, including project staff and program participants such as HEW, schoolteachers, and district-level health staff, which were documented through informal field notes.

2.3. Quantitative Analysis of the Data

2.4. Qualitative Methods

3. Results

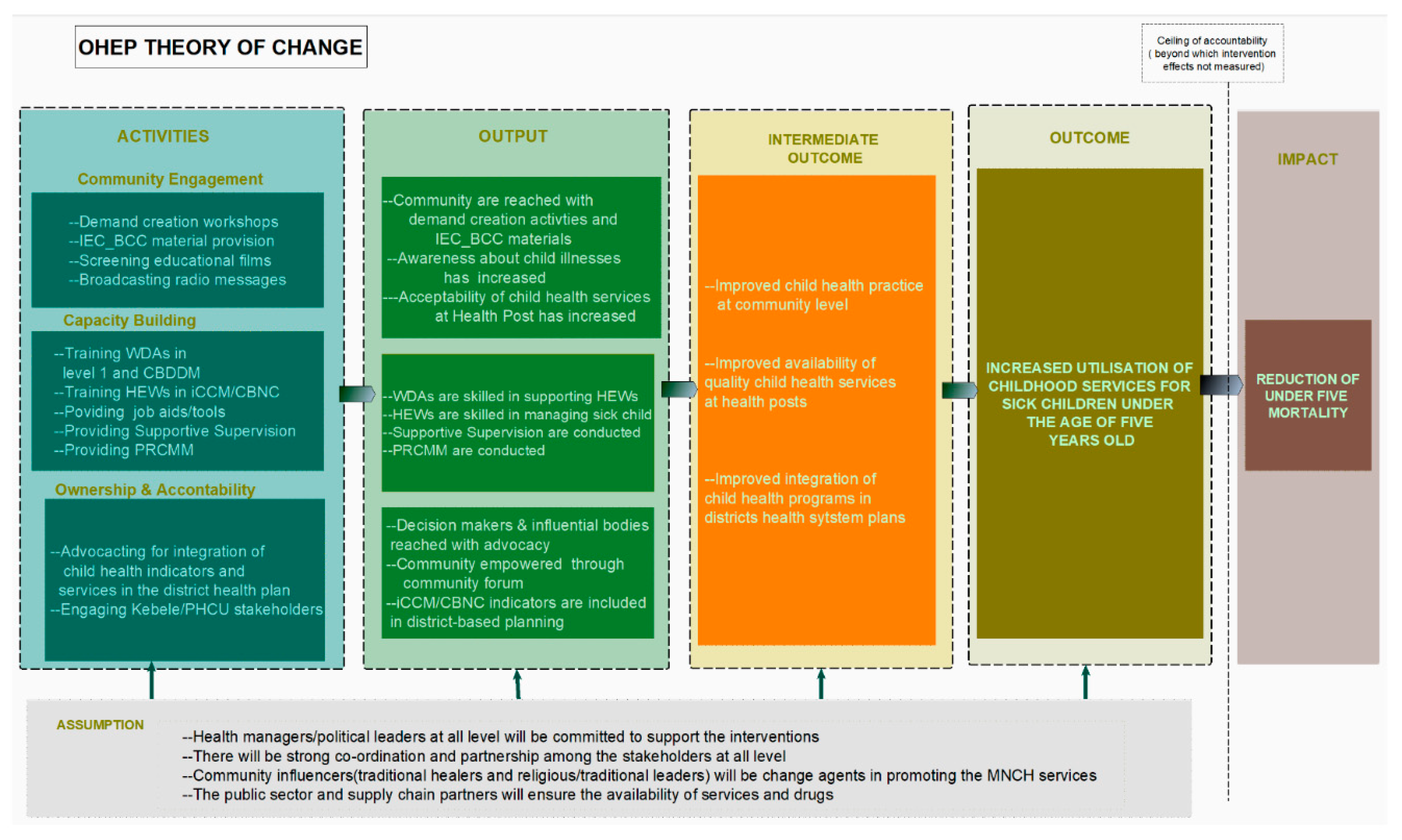

3.1. The Intervention

3.2. Fidelity of Implementation

3.3. Perception of the Intervention and Its Impact

“One of the key factors for the success was developing the theory of change…all partners both from the government and non-government sectors working on maternal and child health were involved. So, having a proper theory of change helped us to understand what the project was going to implement”(NGO Staff 1 at the head office)

“The selected implementing partners were well experienced, so they did not have any difficulty to implement the project. X and Y [names of implementing NGOs] have been working on child health for many years”(NGO Staff 2 at the head office)

“What OHEP used was the existing structure. It has no parallel…The program was not about bringing change by creating a new structure. It was building capacity by employing new activities that were not dependant on modern technologies”(NGO Staff 3 at the head office)

“After the open house session people have known what is provided in at health posts, and that the HEWs and the services are there for the community, which has increased their interest in using health post services”(Government Staff 1 at Regional Health Bureau)

“When we trained and supported them [HEWs], we saw that they had skill gaps. Thus, after training they knew more about their work and they showed a better performance and I think the change was very good”(Government Staff 2 at Regional Health Bureau)

3.4. Experience and Perception of Implementation Challenges

3.4.1. Complexity

Multiple Components

“This is because it [open houses] needs the involvement of the community participation. It is at the community forum [workshops] that the date of the open house session is decided. The health post incurs costs to get renovation and needed the participation of the community, these things have taken some time”(NGO Staff 4 at district office)

“The duration of implementation was very short, and this kind of strategy needs time…. Convincing the community about their problem and convincing them that they can solve their problem is time taking. So, it needs time to introduce new idea and to let it mature but our strategy did not think of that”(NGO Staff 5 at the head office)

“The first months were about hiring staff, equipping, and providing orientation about the project. The process of signing agreement takes time. And then at the end of the project, evaluation of the project is performed with the government. So, the duration of the implementation phase was short. When the second project [after interruption] started again, the process started all over again. There was lots of time wasted”(NGO Staff 6 at regional office)

Administrative Challenges

“It shouldn’t have been interrupted because it was a hot time or peak time for the implementation. We were already delayed in starting the implementation”(NGO Staff 7 at head office)

“I wouldn’t be exaggerating to say, we used to go out to the field the whole 11 months. We didn’t have breaks even on weekends. We were expected to complete a 2-year project within 1 year and 3 months”(NGO Staff 8 at district office)

“If all partners could have purchased it from a single place, if the donor made the purchase process from a single place, it would have been fast. All have their own purchasing system and that was the reason for the delay”(NGO Staff 9 at the head office)

3.4.2. Support and Engagement of Health Managers

“When other partners come, they discuss with the bureau and once they have started implementing, we only meet at the last review meeting. But with OHEP, we plan together, we train together and support the performance together”(Government Staff 1 at Regional Health Bureau)

“Most of the challenges when you work with government is their other competitive priorities, otherwise they were positive when they were working with us”(Government Staff 6 at district office)

“For instance, after we have planned certain activities to implement with health bureau, the plan will be postponed due to different reason such as trachoma campaign or immunisation campaign and so on”(Government Staff 9 at district office)

“The head of the district offices, directors of the health centres did not do follow up as if it [the program] was their own”(District Government Staff 6)

“When they [health office staff] inquire about the project, they used to say, ‘What did you do with X’s [name of implementing NGO] project?’. They didn’t call the project as their own”(NGO Staff 3 at district office)

3.4.3. Health Extension Workers as Catalytic Actors

“I can say health extension workers have phased out; they don’t have motivation”(Government Staff 3 at Regional Health Bureau)

“But some extension workers do not work as asked. They train 30 women [WDAs] first and they were supposed to continue with the next 30 women, but they do not perform that, they stop with the first training. I’m still asking them to train”(Government Staff 2 at Regional Health Bureau)

3.4.4. Shortage of Supervisory Staff and Transport on the Ground

“There is a focal person that supports this program in each district but there should have been additional professionals on the ground”(NGO Staff 4 at district office)

“When the health centre has a vehicle, they don’t have fuel. Or they need to have a motor bike, but they do not have one and even if they do, they don’t have fuel”(Government Staff 7 at district office)

“We deliver posters to the districts…the district may receive the materials but never distribute them”(NGO Staff 5 at district office)

3.4.5. External Environment

“The major challenge that we faced was instability. After we have done well then, the instability happens, so we leave”(NGO Staff 1 at head office)

“Some districts are accessible, and others are very remote. It may take three or four hours walking to reach some health posts”(Government Staff 1 at head office)

“When there is an outbreak the government forces us to focus on the outbreak or their focus will be diverted, and they will focus on the outbreak”(NGO Staff 8 at the head office)

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Availability of Data and Materials

Trial registration

References

- Medhanyie, A.; Spigt, M.; Kifle, Y.; Schaay, N.; Sanders, D.; Blanco, R.; GeertJan, D.; Berhane, Y. The role of health extension workers in improving utilization of maternal health services in rural areas in Ethiopia: A cross sectional study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health. Available online: https://www.africanchildforum.org/clr/policy%20per%20country/ethiopia/ethiopia_nutrition_2003_en.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- Ruducha, J.; Mann, C.; Singh, N.S.; Gemebo, T.D.; Tessema, N.S.; Baschieri, A.; Friberg, I.; Zerfu, T.A.; Yassin, M.; Franca, G.A.; et al. How Ethiopia achieved Millennium Development Goal 4 through multisectoral interventions: A Countdown to 2015 case study. Lancet Glob. Health 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boerma, T.; Requejo, J.; Victora, C.G.; Amouzou, A.; George, A.; Agyepong, I.; Barroso, C.; Barros, A.J.D.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Black, R.E.; et al. Countdown to 2030: Tracking progress towards universal coverage for reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health. Lancet 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noordam, A.C.; Carvajal-Velez, L.; Sharkey, A.B.; Young, M.; Cals, J.W.L. Care seeking behaviour for children with suspected pneumonia in countries in sub-Saharan Africa with high pneumonia mortality. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinmegn Mihrete, T.; Asres Alemie, G.; Shimeka Teferra, A. Determinants of childhood diarrhea among underfive children in Benishangul Gumuz Regional State, North West Ethiopia. BMC Pediatr. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defar, A.; Okwaraji, Y.B.; Tigabu, Z.; Persson, L.Å.; Alemu, K. Geographic differences in maternal and child health care utilization in four Ethiopian regions: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Equity Health 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okwaraji, Y.B.; Cousens, S.; Berhane, Y.; Mulholland, K.; Edmond, K. Effect of geographical access to health facilities on child mortality in rural Ethiopia: A community based cross sectional study. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e33564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getachew, T.; Mekonnen, S.; Yitayal, M.; Persson, L.Å.; Berhanu, D. Health extension workers’ diagnostic accuracy for common childhood illnesses in four regions of Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Acta Paediatr. Int. J. Paediatr. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuneh, A.D.; Medhanyie, A.A.; Bezabih, A.M.; Persson, L.Å.; Schellenberg, J.; Okwaraji, Y.B. Wealth-based equity in maternal, neonatal, and child health services utilization: A cross-sectional study from Ethiopia. Int. J. Equity Health 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmusharaf, K.; Byrne, E.; O’Donovan, D. Strategies to increase demand for maternal health services in resource-limited settings: Challenges to be addressed. BMC Public Health 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, A.; Hodge, A.; Jimenez-Soto, E.; Morgan, A. What works? Strategies to increase reproductive, maternal and child health in difficult to access mountainous locations: A systematic literature review. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Prado, A. Changing behavioral patterns related to maternity and childbirth in rural and poor populations: A critical review. World Bank Res. Obs. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.; Campbell, R.; Hildon, Z.; Hobbs, L.; Michie, S. Theories of behaviour and behaviour change across the social and behavioural sciences: A scoping review. Health Psychol. Rev. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Literature Review on Barriers to Utilization of Health Extension Services: Draft Report. Available online: https://www.childhealthtaskforce.org/sites/default/files/2019-05/Literature%20Review%20on%20Barriers%20to%20Utilization%20of%20Health%20Extension%20Services%20Draft%20Report%28UNICEF%2CPATH%2C2016%29.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- Berhanu, D.; Okwaraji, Y.B.; Belayneh, A.B.; Lemango, E.T.; Agonafer, N.; Birhanu, B.G.; Abera, K.; Betemariam, W.; Medhanyie, A.A.; Abera, M.; et al. Protocol for the evaluation of a complex intervention aiming at increased utilisation of primary child health services in Ethiopia: A before and after study in intervention and comparison areas. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berhanu, D.; Okwaraji, Y.B.; Defar, A.; Belayneh, A.B.; Lemango, E.T.; Medhanyie, A.A.; Wordofa, M.A.; W/Gebreil, F.; Wuneh, A.D.; Ashebir, F.; et al. Does a complex intervention targeting communities, health facilities and district health managers increase the utilisation of community-based child health services? A before and after study in intervention and comparison areas of Ethiopia. BMJ Open 2020, 10, 35. [Google Scholar]

- UNICO Studies Series 10 The Health Extension Program in Ethiopia. Available online: http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/356621468032070256/pdf/749630NWP0ETHI00Box374316B00PUBLIC0.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- Okwaraji, Y.B.; Berhanu, D.; Persson, L.Å. Community-based child care: Household and health- facility perspectives. LSHTM Res. Online 2017. eprint/4655119. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, T.C.; Glasziou, P.P.; Boutron, I.; Milne, R.; Perera, R.; Moher, D.; Altman, D.G.; Barbour, V.; Macdonald, H.; Johnston, M.; et al. Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnan, L.; Steckler, A. Process evaluation for public health interventions and research. Eval. Program Plann. 2004, 27, 118–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, C.; Patterson, M.; Wood, S.; Booth, A.; Rick, J.; Balain, S. A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implement. Sci. 2007, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.L.; Wawire, V.; Ombunda, H.; Li, T.; Sklar, K.; Tzehaie, H.; Wong, A.; Pelto, G.H.; Omotayo, M.O.; Chapleau, G.M.; et al. Integrating calcium supplementation into facility-based antenatal care services in western Kenya: A qualitative process evaluation to identify implementation barriers and facilitators. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2018, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rwabukwisi, F.C.; Bawah, A.A.; Gimbel, S.; Phillips, J.F.; Mutale, W.; Drobac, P.; Hingora, A.; Mboya, D.; Exavery, A.; Tani, K.; et al. Health system strengthening: A qualitative evaluation of implementation experience and lessons learned across five African countries. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, A.M.; Zemichael, N.F.; Shigute, T.; Altaye, D.E.; Dagnew, S.; Solomon, F.; Hailu, M.; Tadele, G.; Yihun, B.; Getachew, N.; et al. Effects of a community-based data for decision-making intervention on maternal and newborn health care practices in Ethiopia: A dose-response study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawson, R.; Tilley, N. Realistic Evaluation; SAGE: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Durlak, J.A.; DuPre, E.P. Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 41, 327–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, G.F.; Audrey, S.; Barker, M.; Bond, L.; Bonell, C.; Hardeman, W.; Moore, L.; O’Cathain, A.; Tinati, T.; Wight, D.; et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical research council guidance. BMJ 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.T. Practical Program Evaluation: Assessing and Improving Planning, Implementation, and Effectiveness; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Verheijden, M.W.; Kok, F.J. Public health impact of community-based nutrition and lifestyle interventions. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaton, C.L.; Holm, N.; Bottorff, J.L.; Jones-Bricker, M.; Errey, S.; Caperchione, C.M.; Lamont, S.; Johnson, S.T.; Healy, T. Factors that impact the success of interorganizational health promotion collaborations: A scoping review. Am. J. Health Promot. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawe, P. Lessons from complex interventions to improve health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2015, 36, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallas, S.W.; Minhas, D.; Pérez-Escamilla, R.; Taylor, L.; Curry, L.; Bradley, E.H. Community health workers in low- and middle-income countries: What do we know about scaling up and sustainability? Am. J. Public Health 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fetene, N.; Linnander, E.; Fekadu, B.; Alemu, H.; Omer, H.; Canavan, M.; Smith, J.; Berman, P.; Bradley, E. The Ethiopian health extension program and variation in health systems performance: What matters? PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Befekadu, A.; Yitayal, M. Knowledge and practice of health extension workers on drug provision for childhood illness in west Gojjam, Amhara, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Ali, D.; Kennedy, A.; Tesfaye, R.; Tadesse, A.W.; Abrha, T.H.; Rawat, R.; Menon, P. Assessing implementation fidelity of a community-based infant and young child feeding intervention in Ethiopia identifies delivery challenges that limit reach to communities: A mixed-method process evaluation study. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Community Engagement | Activities | Activity Type: One Time Only? | Description | Indicator | No. of Districts That Planned Implementation | Phase 1 Implementation 2016–2017 | Overall Implementation 2016–2018 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | IQR | Median | IQR | ||||||

| Demand creation workshop | Agricultural Extension Workers (AEWs) workshop | Yes | AEWs (1330) to participate in orientation workshop | % of AEWs who participated in the workshop, per district | 22 1 | 88 | 58–100 | 95 | 71–100 |

| Schoolteachers’ workshop | Yes | Schoolteachers (929) to participate in orientation workshop | % of teachers who participated in the workshop, per district | 26 | 100 | 100–100 | 100 | 100–100 | |

| Religious/traditional leaders’ workshop | Yes | Religious/traditional leaders (115) to participate in workshop | % of religious/traditional leaders who participated in the workshop, per district | 18 2 | 100 | 75–100 | 100 | 75–100 | |

| Health-post open-house session | Yes | Open-house session to be completed in 675 health posts | % of health posts which conducted open-house session, per district | 26 | 6 | 0–49 | 96 | 77–100 | |

| IEC/BCC material provision | Family Health Guide | Yes | Family Health Guide (486,041) to be sent to districts for distribution toWDAs 3, HEWs, and families with under five children | % of Family Health Guide sent to districts for distribution to WDAs, HEWs and families with under five children, per district | 26 | 46 | 1–73 | 81 | 72–100 |

| Brochure/factsheets | Yes | Brochure/factsheets (168,750) on childhood danger signs to be sent to districts for distribution to health posts, WDAs, Schools, and AEWs | % of brochure/factsheets sent to districts, for distribution to the community 4, per district | 22 5 | 43 | 17–61 | 89 | 81–100 | |

| Posters for health facilities and the community | Yes | Posters (32,135) on childhood danger signs to be sent to districts for distribution WDAs, HEWS, AEWs, Schools | % of posters sent to districts for distribution to the community 6, per district | 26 | 40 | 0–100 | 91 | 45–100 | |

| Banners for health posts | Yes | Banners (675) to be sent to districts for distribution to health posts | % of banners sent to districts for distribution to health posts (assuming 1 for each health post), per district | 26 | 92 | 50–100 | 100 | 93–100 | |

| Pico projector for health posts | Yes | Pico projectors (675) to be sent to districts for distribution to health posts | % of health posts which received Pico projector (assuming 1 for each health posts), per district | 26 | 0 | 0–83 | 100 | 100–100 | |

| TV/DVD for health centres | Yes | TV/DVD (140) to be sent to districts for distribution to health centres | % health centres which received TV/DVD (assuming 1 for each health centre), per district | 26 | 0 | 0–20 | 42 | 25–100 | |

| Educational films production | Yes | Educational films (13) on new-born and pregnancy danger signs to be produced | % of locally appropriate educational films produced, per district | 26 | 33 | 0–67 | 66 | 33–67 | |

| Speaking book | Yes | Speaking book (486,041) with a sound and picture messages on maternal and child health to be sent to districts for distribution to families with under five children | % of speaking books sent to districts for distribution to households, per district | 26 | 0 | 0–0 | 0 | 0–0 | |

| Radio messages produced | Yes | Radio spots (25) on pregnancy, new-born, and child health to be produced for airing | % of radio spots in local language produced, per district | 26 | 50 | 50–100 | 100 | 100–100 | |

| Radio dramas produced | Yes | Radio dramas (2) on pregnancy, new-born, and child health to be produced for airing | % of radio dramas in local language produced, per district | 18 7 | 50 | 50–100 | 100 | 100–100 | |

| Capacity Building | Activities | Activity Type: One Time Only? | Description | Indicator | No. of Districts That Planned Implementation | Phase 1 Implementation 2016–2017 | Overall Implementation 2016–2018 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | IQR | Median | IQR | ||||||

| Training | iCCM/CBNC training for HEW | Yes | HEWs (1598) to be provided iCCM/CBNC 8 training | % of HEWs who participated in iCCM/CBNC training, per district | 26 | 22 | 3–34 | 38 | 12–54 |

| Level-one competency training of trainers for HEW | Yes | HEWs (1598) to be provided level-one competency training of trainers training | % of HEWs who participated in level-one competency training of trainers training, per district | 26 | 0 | 0–100 | 19 | 0–100 | |

| Level-one competency for WDA | Yes | WDAs (22,593) to be provided level-one competency training | % of WDAs who participated in level-one competency training, per district | 26 | 0 | 0–0 | 0 | 0–21 | |

| CBDDM 9 training of trainers training for HEWs | Yes | HEWs (1598) to be provided CBDDM Training of trainers training | % of HEWs who participated in CBDDM training of trainers training, per district | 22 10 | 15 | 0–40 | 100 | 60–100 | |

| CBDDM training for WDAs | Yes | WDAs (22,593) to be provided CBDDM training | % of WDAs who participated in CBDDM training, per district | 22 11 | 0 | 0–0 | 73 | 0–100 | |

| Joint supportive supervision | Joint supportive supervision for 50% health centres in the district | No | Joint supportive supervision to be provided to health centres | % of health centres which received joint supervision visits, per district (assuming 4 visits per year) | 26 | 79 | 20–100 | 100 | 34–100 |

| Joint supportive supervision for 25% health posts in the district | No | Joint supportive supervision to be provided for health posts | % of health posts which received joint supervision visits, per district (assuming 4 visits per year) | 26 | 16 | 12–21 | 40 | 29–48 | |

| Performance review and clinical mentoring meeting (PRCMM) | No | PRCMM to be conducted for health posts at district level | % of PRCMM conducted, per district | 26 | 2 | 1–12 | 75 | 35–100 | |

| Job aids and tools provision | WDA–HEW linkage card | Yes | WDA–HEW linkage cards (86,961) to be sent to Woreda, for distribution for WDAs | % of WDA–HEW linkage cards sent to district for distribution to WDAs per district | 18 12 | 0 | 0–0 | 13 | 0–100 |

| Backpack for HEWs | Yes | Backpacks (675) to be sent to district for distribution to HEWs | % of backpacks sent to district, for distribution to HEWs (assuming 1 per health post), per district | 26 | 27 | 0–100 | 100 | 100–100 | |

| Registration book (0–2) | Yes | Registration books (0–2) (675) to be sent to district for distribution to HEWs | % of registration books (0–2 months) sent to district, for distribution to health posts (assuming 1 per health posts), per district | 18 13 | 0 | 0–0 | 100 | 0–100 | |

| Registration book (2–59) | Yes | Registration books (2–59) (675) to be sent to district for distribution to HEWs | % of registration books (2–59 months) sent to district, for distribution to health posts (assuming 1 per health post), per district | 18 14 | 0 | 0–0 | 100 | 0–100 | |

| Chart booklet | Yes | Chart booklets (675) to be sent to district for distribution to health posts | % of chart booklets sent to district, for distribution to health posts (assuming 1 per health post), per district | 18 15 | 0 | 0–0 | 62 | 0–100 | |

| Ownership and Accountability | Activities | Activity Type: One Time Only? | Description | Indicator | No. of Districts That Planned Implementation | Phase 1 Implementation 2016–2017 | Overall Implementation 2016–2018 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | IQR | Median | IQR | ||||||

| Ownership-and-accountability workshops | District-level advocacy workshop | Yes | District staff (1397) to participate in advocacy workshop | % of district staff who participated in advocacy workshop, per district | 26 | 52 | 44–100 | 52 | 44–100 |

| Kebele/PHCU 16 stakeholders’ workshop | Yes | Kebele/PHCU stakeholders (2, 422) to participate in stakeholder workshop | % of stakeholders who participated in kebele/PHCU stakeholders’ workshop, per district | 26 | 100 | 0–100 | 100 | 82–100 | |

| Community forum | Yes | Stakeholders (12,034) to participate in the workshop | % of stakeholders participated in the workshop, per district | 26 | 22 | 0–81 | 79 | 19–96 | |

| Annual district-based Planning | No | Annual district-based planning sessions (66) to be attended by implementers | % of annual district-based planning session in which implementers participated, per district (assuming 1 participation per year) | 26 | 33 | 33–67 | 67 | 67–100 | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Okwaraji, Y.B.; Hill, Z.; Defar, A.; Berhanu, D.; Wolassa, D.; Persson, L.Å.; Gonfa, G.; Schellenberg, J.A. Implementation of the ‘Optimising the Health Extension Program’ Intervention in Ethiopia: A Process Evaluation Using Mixed Methods. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5803. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165803

Okwaraji YB, Hill Z, Defar A, Berhanu D, Wolassa D, Persson LÅ, Gonfa G, Schellenberg JA. Implementation of the ‘Optimising the Health Extension Program’ Intervention in Ethiopia: A Process Evaluation Using Mixed Methods. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(16):5803. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165803

Chicago/Turabian StyleOkwaraji, Yemisrach B., Zelee Hill, Atkure Defar, Della Berhanu, Desta Wolassa, Lars Åke Persson, Geremew Gonfa, and Joanna A. Schellenberg. 2020. "Implementation of the ‘Optimising the Health Extension Program’ Intervention in Ethiopia: A Process Evaluation Using Mixed Methods" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 16: 5803. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165803

APA StyleOkwaraji, Y. B., Hill, Z., Defar, A., Berhanu, D., Wolassa, D., Persson, L. Å., Gonfa, G., & Schellenberg, J. A. (2020). Implementation of the ‘Optimising the Health Extension Program’ Intervention in Ethiopia: A Process Evaluation Using Mixed Methods. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(16), 5803. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165803