A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review: Infidelity, Romantic Jealousy and Intimate Partner Violence against Women

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Defining Terminology

1.2. Relational Level Drivers of Intimate Partner Violence

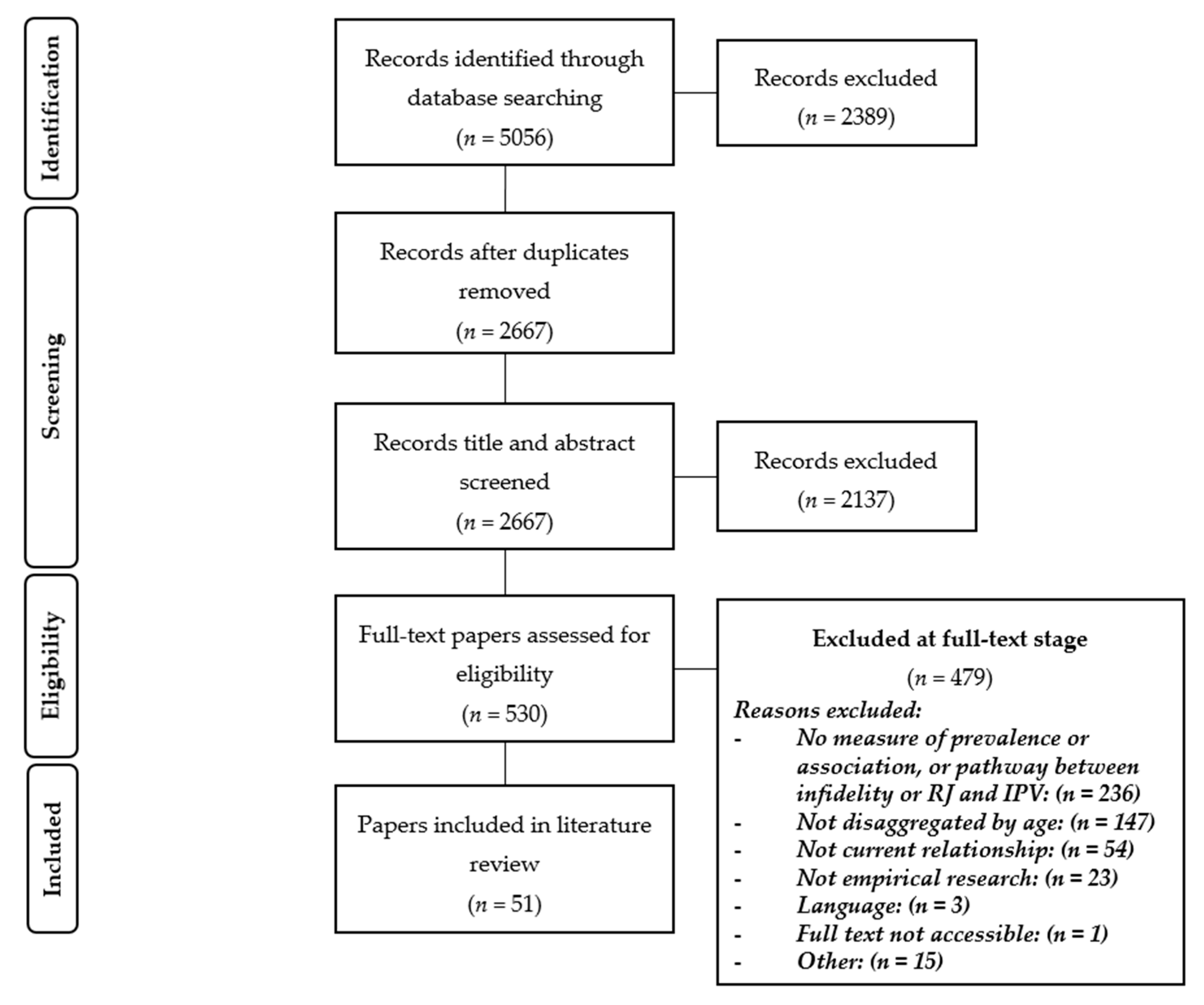

2. Methods

2.1. Design and Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Screening

2.4. Data Extraction and Analyses

2.5. Quality Appraisal

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Summary of Included Quantitative Studies

3.3. Measurement of Infidelity and RJ

3.4. Measurement of IPV

3.5. Frequency of Infidelity or RJ as a Reason for IPV

3.6. IPV Outcomes and Associations with Infidelity or RJ

3.7. Underlying Mechanisms of Association between Infidelity, RJ and IPV

3.8. Summary of Qualitative Results

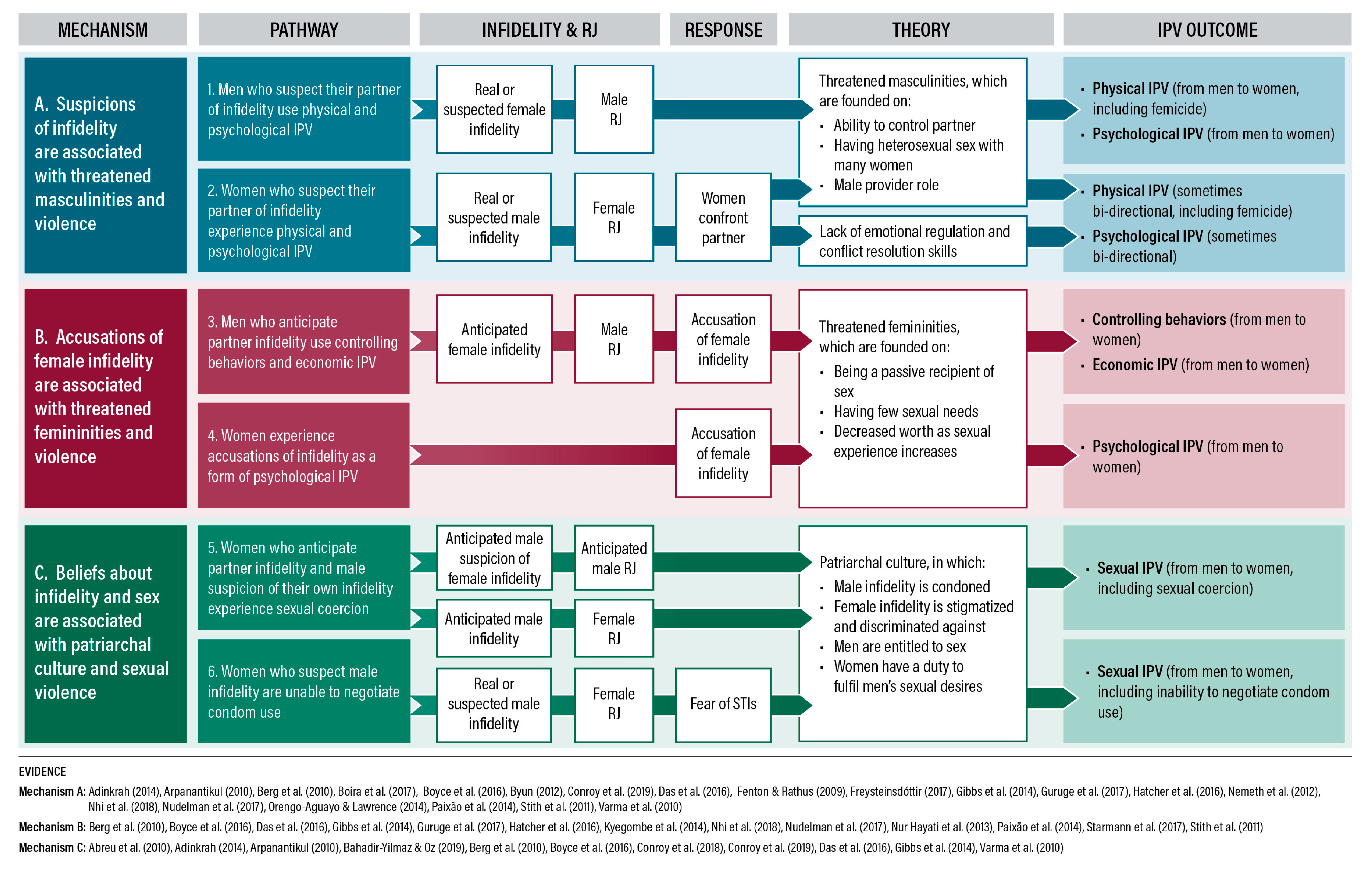

3.9. Identified Mechanisms and Pathways from Infidelity and RJ to IPV

3.9.1. Mechanism A: Suspicions of Infidelity Are Associated with Threatened Masculinities and Violence

“Most [participants] said that their husband became suspicious when they (the wife) questioned them concerning their [sexual] behaviors while drinking. This suspicion frequently resulted in the husband physically or verbally abusing them. The women said that their husbands often assumed such questions reflected the wife’s own infidelity, which further angered the husbands”[103] (p. 818)

“That’s what really made me snap when you said, ‘go fuck [male friend], go fuck [male friend], go back to your boyfriend…” That really hurt my whole manhood, my dignity, my pride, my everything”[95] (p. 945)

3.9.2. Mechanism B: Accusations of Female Infidelity Are Associated with Threatened Femininities and Violence

“This man used to keep his wife inside the house, when he goes to work, he locks the door and sweeps the garden neatly, so that [he will know] if someone comes to the house [because] they will leave foot prints [in the sand]”[92] (p. 7).

“As you know women admire a lot and so at work is where she might find someone to admire her and then change her mind into cheating”[94] (p. 5)

“He directly came to the school principal and raised negative speculations [accused her of infidelity] that ruined my reputation. He said, “if something bad happened in the future at this school, don’t blame me as I’ve already warned you about her.” So the next day the principal called me and cancelled my promotion for the master program”[98] (p. 6)

“If I’m not interested in her, I don’t care what she does. If she goes out with some person, she can do what she wants with her life. But if I had feelings for her, it will affect [hurt] me”[84] (p. 627)

“Lots of swearing at me, abusing me, saying that the child was not his… After we had the child it became worse… So all the agony began, the bad relationship, him complaining about everything, saying that I should’ve taken care of myself (the pregnancy) [had an abortion]”[100] (p. 1044)

“On a few occasions I would be so hungry that I ate my meal before. That made him so angry that he berated me and said, ‘You probably have another husband whom you fed first and that’s why you have had your food before me.’”[88] (p. 113)

3.9.3. Mechanism C: Beliefs about Infidelity and Sex Are Associated with Patriarchal Culture and Sexual Violence

“My sister-in-law and my mother also told me that men go to other women when his wife did not satisfy him [sexually]. So when he wants to do [have sex] I make myself ready”[82] (p. 132)

“I felt dishonored when others knew my husband had engaged in an affair with another woman. Some friends looked down on me and said I could not control my husband. It looked like I could not complete the roles of a wife… some gossiped and told me… I might have something wrong with me so he couldn’t stand me... It is my karma in my past life that made me live with my husband in this life”[80] (p. 352)

4. Discussion and Implications for Research and Programs

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Programing Implications

4.3. Gaps in the Literature

4.4. Measurement Implications

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Database | Search Script for Intimate Partner Violence | Search Script for Infidelity and Romantic Jealousy |

|---|---|---|

| ASSIA (Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts) | MAINSUBJECT.EXACT.EXPLODE(“Domestic violence”) OR MAINSUBJECT.EXACT.EXPLODE(“Battered women”) OR ((DE=”domestic violence”) or (DE=“battered women”) or (abuse* within 3 wom*n) or (abuse* within 3 spous*) or (abuse* within 3 partner*) or ((wife within 3 abuse*) or (wives within3 abuse*)) or ((wife within 3 batter*) or (wives within 3 batter*)) or (partner* within 3 violen*) or (spous* within 3 violen*)) | MAINSUBJECT.EXACT.EXPLODE(“Jealousy”) OR MAINSUBJECT.EXACT.EXPLODE(“Marital infidelity”) OR ((jealous*) or (infidelit*) or (“sexual affair*”) or (unfaithful*) or (adultery) or (adulterer) or (extramarital) or (“controlling behaviour*”) or (“controlling behavior*”)) |

| CENTRAL (Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials) | #1 (battered wom*n): ti #2 (battered wom*n): ab #3 MeSH descriptor: [Battered Women] explode all trees #4 MeSH descriptor: [Domestic Violence] this term only #5 MeSH descriptor: [Gender-Based Violence] this term only #6 MeSH descriptor: [Intimate Partner Violence] explode all trees #7 MeSH descriptor: [Spouse Abuse] explode all trees #8 abuse near/3 (woman or women): ti #9 abuse near/3 (woman or women): ab #10 abuse* near/3 partner*: ti #11 abuse* near/3 partner*: ab #12 abuse* near/3 spouse*: ti #13 abuse* near/3 spouse*: ab #14 wife near/3 batter* or wives near/3 batter*: ti #15 wife near/3 batter* or wives near/3 batter*: ab #16 wife* near/3 abuse* or wives near/3 abuse*: ti #17 wife* near/3 abuse* or wives near/3 abuse*: ab #18 violen* near/3 partner* or violen* near/3 spous*: ti #19 violen* near/3 partner* or violen* near/3 spous*: ab #20 violen* near/3 date or violen* near/3 dating:ti #21 violen* near/3 date or violen* near/3 dating:ab #22 #1or#2or#3or#4or#5or#6or#7or#8or#9or#10or#11or#12or#13or#14or#15or#16or#17or#18 or#19or#20or#21 | #23 MeSH descriptor: [Jealousy] explode all trees #24 MeSH descriptor: [Extramarital Relations] explode all trees #25 jealous*: ti #26 jealous*: ab #27 infidelity:ti #28 infidelity:ab #29 sexual affair:ti #30 sexual affair:ab #31 unfaithful*: ti #32 unfaithful*: ab #33 adultery:ti #34 adultery:ab #35 adulterer:ti #36 adulterer:ab #37 extramarital:ti #38 extramarital:ab #39 “controlling behavior”: ti #40 “controlling behavior”:ab #41 “controlling behaviour”:ti #42 “controlling behaviour”: ab #43 #23or#24or#25or#26or#27or#28or#29or#30or#31or#32or#33 or#34or#35or#36or#37or#38or#39or#40or#41or#42 #44 #22and#43 |

| CINAHL (Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature) | S10 S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 OR S5 OR S6 OR S7 OR S8 OR S9 S9 TI (domestic violence) or AB (domestic violence) S8 TI (partner* or spouse* or gender) N3 (violen*)) or AB (partner* or spouse* or gender) N3 (violen*)) S7 TI (batter* N3 (wom?n or wife or wives)) or AB(batter* N3 (wom?n or wife or wives)) S6 TI (abuse* N3 (wom?n or spouse* or partner* or wife or wives))or AB (abuse* N3 (wom?n or spouse* or partner* or wife or wives)) S5 (MH “Gender-Based Violence) S4 (MH “Dating Violence”) S3 (MH “Battered Women”) S2 (MH “Domestic Violence”) S1 (MH “Intimate Partner Violence”) | S23 S10 AND S22 S22 S11 OR S12 OR S13 OR S14 OR S15 OR S16 OR S17 OR S18 OR S19 OR S20 OR S21 S21 TI (extramarital) or AB (extramarital) S20 TI (“controlling behavior”) or AB (“controlling behavior”) S19 TI (“controlling behaviour”) or AB (“controlling behaviour”) S18 TI (adulterer) or AB (adulterer) S17 TI (adultery) or AB (adultery) S16 TI (unfaithful*) or AB (unfaithful*) S15 TI (“sexual affair”) or AB (“sexual affair”) S14 TI (infidelity) or AB (infidelity) S13 TI (jealous*) or AB (jealous*) S12 (MH “Jealousy”) S11 (MH “Extramarital Relations”) |

| Embase (Excerpta Medica Database) | Battered Woman/ OR domestic violence/ or intimate partner violence/ or family violence/ or battering/ OR (abuse adj3 (woman or women)) OR (abuse$ adj3 partner$) OR (abuse$ adj3 spouse$) OR ((wife or wives) adj3 batter$) OR ((wife or wives) adj3 abuse$) OR (violen$ adj3 partner$) OR (violen$ adj3 spous$) OR (violen$ adj3 (date or dating)) | Jealousy/ or extramarital sexual intercourse/ or ((jealous*) or (infidelit*) or (“sexual affair*”) or (unfaithful*) or (adultery) or (adulterer) or (extramarital) or (“controlling behaviour*”) or (“controlling behavior*”)) |

| Social Policy and Practice | ||

| IBSS (International Bibliography of the Social Sciences) | (MAINSUBJECT.EXACT(“Domestic violence”) OR ((TI((“family violence”) or (“domestic violence”) or (“dat* violence”))) OR (AB((“family violence”) or (“domestic violence”) or (“dat* violence”))) OR ((TI((violen* near/3 (wom*n or partner* or spous* or wife or wives)))) OR (AB((violen* near/3 (wom*n or partner* or spous* or wife or wives)))) OR (AB((batter* near/3 (wom*n or partner* or spous* or wife or wives)))) OR (TI((batter* near/3 (wom*n or partner* or spous* or wife or wives)))) OR ((TI((abuse* near/3 (wom*n or partner* or spous* or wife or wives)))) OR (AB((abuse* near/3 (wom*n or partner* or spous* or wife or wives))))) OR (TI((abuse* near/3 (wom*n or partner* or spous* or wife or wives)))) OR (AB((abuse* near/3 (wom*n or partner* or spous* or wife or wives)))))) | (MAINSUBJECT.EXACT.EXPLODE(“Adultery”) OR ((jealous*) or (infidelit*) or (“sexual affair*”) or (unfaithful*) or (adultery) or (adulterer) or (extramarital) or (“controlling behaviour*”) or (“controlling behavior*”)) |

| Medline (Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online) | Battered Women/ OR Domestic Violence/ OR Spouse abuse/ OR intimate partner violence OR (abus$ adj3 partner$) OR (abus$ adj3 wom#n$) OR (abus$ adj3 spous$) OR ((wife or wives) adj3 batter$) OR ((wife or wives) adj3 abuse$) OR (violen$ adj3 partner$) OR (violen$ adj3 spous$) OR (violen$ adj3 (date or dating)) | Jealousy/ or Extramarital relations/ or ((jealous*) or (infidelit*) or (“sexual affair*”) or (unfaithful*) or (adultery) or (adulterer) or (extramarital) or (“controlling behaviour*”) or (“controlling behavior”*)) |

| PsycINFO (Psychological Information) | 1 Battered Females/ 2 Domestic Violence/ 3 Intimate Partner Violence/ 4 (Partner Abuse.ab.) or (partner abuse.ti.) 5 (abuse$ adj3 wom#n).ab. or (abuse$ adj3 wom#n).ti. 6 (abuse$ adj3 spous$).ab. or (abuse$ adj3 spous$).ti. 7 (abuse$ adj3 partner$).ab. or (abuse$ adj3 partner$).ti. 8 (abuse$ adj3 (wife or wives)).ab. or (abuse$ adj3 (wife or wives)).ti. 9 (batter$ adj3 wom#n).ab. or (batter$ adj3 wom#n).ti. 10 (batter$ adj3 (wife or wives)).ab. or (batter$ adj3 (wife or wives)).ti. 11 (partner$ adj3 violen$).ab. or (partner$ adj3 violen$).ti. 12 (spous$ adj3 violen$).ab. or (spous$ adj3 violen$).ti. 13 (domestic violence).ab. or (domestic violence).ti. 14 (gender adj3 violen$).ab. or (gender adj3 violen$).ti. 15 or/1-14 | 16 jealousy/ 17 infidelity/ 18 extramarital intercourse/ 19 (unfaithfulness).ab. or (unfaithfulness).ti.20 (adultery).ab. or (adultery).ti. 21 (adulterer).ab or (adulterer).ti. 22 (sexual affair).ab. or (sexual affair).ti. 23 (controlling behaviour).ab. or (controlling behaviour).ti. 24 (controlling behavior).ab. or (controlling behavior).ti. 25 or/ 16-24 26 and/ 15, 24 |

| Social Services Abstracts | MAINSUBJECT.EXACT.EXPLODE(“Spouse Abuse”) OR MAINSUBJECT.EXACT.EXPLODE(“Battered Women”) OR MAINSUBJECT.EXACT.EXPLODE(“Partner Abuse”) OR MAINSUBJECT.EXACT.EXPLODE(“Family Violence”) OR (SU.EXACT((“Family violence”)) OR SU.EXACT((“Partner Abuse”) OR (“Battered Women”)) OR (abuse NEAR/3 wom*n) OR (abuse NEAR/3 spouse*) OR (abuse NEAR/3 partner*) OR (wife NEAR/3 abuse*) OR (wives NEAR/3 abuse*) OR (wife NEAR/3 batter*) OR (wives NEAR/3 batter*) OR (women NEAR/3 batter*) OR (partner* NEAR/3 violen*) OR (spouse* NEAR/3 violen*) OR (gender NEAR/3 violen*) OR (“domestic violence”)) | MAINSUBJECT.EXACT.EXPLODE(“Jealousy”) OR MAINSUBJECT.EXACT.EXPLODE(“Infidelity”) OR ((jealous*) or (infidelit*) or (“sexual affair*”) or (unfaithful*) or (adultery) or (adulterer) or (extramarital) or (“controlling behaviour*”) or (“controlling behavior*”)) |

| Sociological Abstracts | ||

| Web of Science | 1 TI = ((family violence) or (domestic violence) or (dat* violence)) 2 AB = ((family violence) or (domestic violence) or (dat* violence)) 3 TI = ((violen* near/3 (wom*n or partner* or spous* or wife or wives))) 4 AB = ((violen* near/3 (wom*n or partner* or spous* or wife or wives))) 5 AB = ((batter* near/3 (wom*n or partner* or spous* or wife or wives))) 6 TI = ((batter* near/3 (wom*n or partner* or spous* or wife or wives))) 7 TI = ((abuse* near/3 (wom*n or partner* or spous* or wife or wives))) 8 AB = ((abuse* near/3 (wom*n or partner* or spous* or wife or wives))) 9 TI = ((abuse* near/3 (wom*n or partner* or spous* or wife or wives))) 10 AB = ((abuse* near/3 (wom*n or partner* or spous* or wife or wives))) 11 1 OR 2 OR 3 OR 4 OR 5 OR 6 OR 7 OR 8 OR 9 OR 10 | 12 TI = ((jealous*) or (infidelit*) or (“sexual affair*”) or (unfaithful*) or (adultery) or (adulterer) or (extramarital) or (“controlling behaviour*”) or (“controlling behavior*”)) 13 AB = ((jealous*) or (infidelit*) or (“sexual affair*”) or (unfaithful*) or (adultery) or (adulterer) or (extramarital) or (“controlling behaviour*”) or (“controlling behavior*”)) 14 12 OR 13 |

Appendix B

| Author (Year) | External Validity | Internal Validity | Quality Assessment | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Response Rate | Non-Response Bias | Missing Data | Study Subjects | Appropriateness | IPV Measure | Infidelity or RJ Measure | TOTAL (Out of 8) | Quality 1 | |

| Alan et al. (2016a) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | ★☆☆☆ |

| Alan et al. (2016b) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ★☆☆☆ |

| Ansara and Hindin (2009) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | ★★★★ |

| Chuemchit et al. (2018) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ★★★☆ |

| Conroy (2014) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | ★★★☆ |

| Edelstein (2018) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 | ★★★☆ |

| Goetz and Shackelford (2009) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | ★★☆☆ |

| Graham-Kevan and Archer (2011) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | ★☆☆☆ |

| Guay et al. (2016) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | ★★☆☆ |

| Kalokhe et al. (2018) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | ★★☆☆ |

| Kerr and Capaldi (2011) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ★★★☆ |

| LaMotte et al. (2018) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | ★★★☆ |

| Madsen et al. (2012) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | ★★☆☆ |

| McKay et al. (2018) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | ★★☆☆ |

| Messing et al. (2014) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | ★★☆☆ |

| Paat et al. (2017) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 | ★★★☆ |

| Salwen and O’Leary (2013) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | ★★★★ |

| Shrestha et al. (2016) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | ★★☆☆ |

| Snead et al. (2019) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | ★★☆☆ |

| Stieglitz et al. (2011) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | ★★☆☆ |

| Stieglitz et al. (2012) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | ★☆☆☆ |

| Toprak and Ersoy (2017) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | ★★☆☆ |

| Townsend et al. (2011) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | ★☆☆☆ |

| Ulibarri et al. (2010) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | ★☆☆☆ |

| Wang et al. (2009) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | ★★☆☆ |

Appendix C

| Type of Measure | Measure Description | Author (Year) |

|---|---|---|

| Validated questionnaire or scale | Questionnaire developed from the WHO multi country study on women’s health and domestic violence. Controlling behaviours scale included: “got angry if female partner spoke with another man”, and “suspicious that female partner is unfaithful” [52]. | Chuemchit et al. (2018) |

| Authors developed the Perception of Aggression Scale: “What led you to…” Answer option includes: “because I was jealous” [57]. | Guay et al. (2016) | |

| Conflict Tactics Scale - 2 Negotiation Subscale: “Extent of jealousy if spouse talks to men within family”, “Extent of jealousy if spouse talks to men outside family”. Also asked: “Engagement in sexual relations outside of spouse?” (“Yes” or “No”) [58]. | Kalokhe et al. (2018) | |

| Modified Relationship Problem Scale [60]. | LaMotte et al. (2018) | |

| Relationship Jealousy Scale (e.g., “How intense are your feelings of jealousy in your current relationship?”) 1-7 scale, “not at all” to “very” [61]. | Madsen et al. (2012) | |

| Revised Conflict Tactic Scale (e.g., “How often does partner become jealous or possessive”, “you know you can count on your partner to remain faithful to you”). Likert scale [62]. | McKay et al. (2018) | |

| Psychological Maltreatment of Women Scale. Jealousy measure is a 12 items scale derived from a factor analysis. Jealousy score was based on an average of the scores of the husband and wife [65]. | Salwen and O’Leary (2013) | |

| Multidimensional Jealousy Scale. This includes 3 subscales for cognitive, emotional and behavioural Jealousy. Emotional jealousy assessed how “upset” partners would feel in response to various jealousy-evoking situations. Behavioural jealousy measured how often partners engaged in various protective behaviours (i.e., verbal attack of possible relationship competitors) and detective behaviours (i.e., going through their partner’s belongings) [67]. | Snead et al. (2019) | |

| Continuous or Likert scale questions developed by authors | Self-reported marital infidelity: “how many people they had sex with in the past 4 months/12 months” (including spouses). Perceived likelihood of partner having an affair: “My partner is probably having sex with someone else”. One to four scale, “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” [53]. | Conroy (2014) |

| Partners past infidelities: “As far as you know, has your current partner had sexual intercourse with someone other than you since you have been involved in a relationship together?”, “As far as you know, has your current partner fallen in love with someone other than you since you have been involved in a relationship together?” Likelihood of committing an infidelity: “How likely do you think it is that your current partner will in the future have sexual intercourse with someone other than you, while in a relationship with you?” “How likely do you think it is that your current partner will in the future fall in love with someone other than you, while in a relationship with you?”. Ten point scale: definitely not/not at all likely–definitely yes/extremely likely. Male infidelity measurement not specified [55]. | Goetz and Shackelford (2009) | |

| Frequency of disagreements stemming from partner’s jealousy, respondent’s commitment, partner’s commitment. Five point scale: “never argue about this” to “always argue about this” [56]. | Graham-Kevan and Archer (2011) | |

| Number of physically abusive events/Frequency of disagreements stemming from partner’s jealousy, respondent’s commitment, partner’s commitment. Five point scale: “never argue about this” to “always argue about this” [68]. | Stieglitz et al. (2011) | |

| Multiple choice or binary [yes/no] questions | Controlling behaviour by the husband was assessed with two items: (a) “your husband or partner won’t let you wear certain things”, and (b) “your husband or partner tells you who you can spend time with” [51]. | Ansara and Hindin (2009) |

| Sexual jealousy: “Is your partner violently and constantly jealous of you? (For instance, does your partner say, ‘If I can’t have you, no one can?’)” [63]. | Messing et al. (2014) | |

| “During the time you were together as a couple, do you think (the father of your child) ever cheated on you with another person after (child’s) birth” [64]? | Paat et al. (2017) | |

| Husband extramarital relationship (“Yes”, “No” or “Don’t Know”) [66]. | Shrestha et al. (2016) | |

| “Do you think your partner has other sexual partners?” (“Yes” or “No”). “Think about the last 3 months, have you been in a sexual relationship with a woman whilst still having a sexual relationship with another?” (“Yes” or “No”) [71]. | Townsend et al. (2011) | |

| “Since you have been together, has your spouse or steady partner had sex with another partner?” (“Yes” or “No”) [72]. | Ulibarri et al. (2010), | |

| “How often do you feel jealous or quite insecure about your partner?” (“never/rarely” or “sometimes/often”). Same question asked to partner [73]. | Wang et al. (2009) | |

| Open-ended questions | “What are the reasons for domestic violence given by your husband” [49]? | Alan et al. (2016a) |

| “What is the reason for violence in your opinion” [50]? | Alan et al. (2016b) | |

| “What are the worst arguments with your spouse in the past year, and throughout your marriage in other years” [69]? | Stieglitz et al. (2012) | |

| Observational | Content analysis of court documents to determine motives of intimate partner homicide [54]. | Edelstein (2018) |

| Motives of femicides coded from legal files [70]. | Toprak and Ersoy (2017) | |

| Mix | Jealousy measure based on two self-report items on the couples interview, partner-reports on the couples interview and the partner issues checklist and one rating from the family and peer process code coder impressions [59]. | Kerr and Capaldi (2011) |

Appendix D

| Author (Year) | Are the Results Valid? | What are the Results? | Will the Results Help Locally? | Quality Assessment | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Was There a Clear Statement of the Aims of the Research? | Is a Qualitative Methodology Appropriate? | Was the Research Design Appropriate to Address the Aims of the Research? | Was the Recruitment Strategy Appropriate to the Aims of the Research? | Was the Data Collected in a Way That Addressed the Research Issue? | Has the Relationship Between Researcher and Participant been Adequately Considered? | Have Ethical Issues been Taken Into Consideration? | Was the Data Analysis Sufficiently Rigorous? | Is There a Clear Statement of Findings? | How Valuable is the Research? | Total (Out of 20) | Quality 1 | |

| Abreu et al. (2010) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 16 | ★★★☆ |

| Adinkrah (2014) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 14 | ★★☆☆ |

| Arpanantikul (2010) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 19 | ★★★★ |

| Bahadir-Yilmaz and Oz (2019) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 11 | ★☆☆☆ |

| Berg et al. (2010) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 17 | ★★★☆ |

| Boira et al. (2017) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 11 | ★☆☆☆ |

| Boyce et al. (2016) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 17 | ★★★☆ |

| Byun (2012) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 11 | ★☆☆☆ |

| Conroy et al. (2018) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 15 | ★★★☆ |

| Conroy et al. (2019) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 17 | ★★★☆ |

| Das et al. (2016) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 13 | ★★☆☆ |

| Fenton and Rathus (2009) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 14 | ★★☆☆ |

| Freysteinsdóttir (2017) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 15 | ★★★☆ |

| Gibbs et al. (2014) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 15 | ★★★☆ |

| Guruge et al. (2017) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 15 | ★★★☆ |

| Hatcher et al. (2016) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 20 | ★★★★ |

| Kyegombe et al. (2014) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 19 | ★★★★ |

| Nemeth et al. (2012) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 17 | ★★★☆ |

| Nhi et al. (2018) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 18 | ★★★★ |

| Nudelman et al. (2017) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 17 | ★★★☆ |

| Nur Hayati et al. (2013) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 15 | ★★★☆ |

| Orengo-Aguayo and Lawrence (2014) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 18 | ★★★★ |

| Paixão et al. (2014) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 12 | ★★☆☆ |

| Starmann et al. (2017) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 15 | ★★★☆ |

| Stith et al. (2011) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 17 | ★★★☆ |

| Varma et al. (2010) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 16 | ★★★☆ |

References

- Devries, K.M.; Mak, J.Y.; García-Moreno, C.; Petzold, M.; Child, J.C.; Falder, G.; Lim, S.; Bacchus, L.J.; Engell, R.E.; Rosenfeld, L. The global prevalence of intimate partner violence against women. Science 2013, 340, 1527–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global and Regional Estimates of Violence Against Women: Prevalence and Health Effects of Intimate Partner Violence and Non-Partner Sexual Violence; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stöckl, H.; Devries, K.; Rotstein, A.; Abrahams, N.; Campbell, J.; Watts, C.; Moreno, C.G. The global prevalence of intimate partner homicide: A systematic review. Lancet 2013, 382, 859–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Understanding and Addressing Violence Against Women; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, A.; Dunkle, K.; Jewkes, R. Emotional and economic intimate partner violence as key drivers of depression and suicidal ideation: A cross-sectional study among young women in informal settlements in South Africa. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cambridge University Press. Cambridge Dictionary. Infidelity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- White, G.L. Jealousy and partner’s perceived motives for attraction to a rival. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1981, 44, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L.; Legerstee, M. Handbook of Jealousy: Theory, Research, and Multidisciplinary Approaches; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salovey, P. Envy and jealousy: Self and society. In The Psychology of Jealousy and Envy; Salovey, P., Ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 271–286. [Google Scholar]

- Puente, S.; Cohen, D. Jealousy and the meaning (or nonmeaning) of violence. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 29, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heise, L. Violence against women: An integrated, ecological framework. Violence Against Women 1998, 4, 262–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Napoli, I.; Procentese, F.; Carnevale, S.; Esposito, C.; Arcidiacono, C. Ending intimate partner violence (IPV) and locating men at stake: An ecological approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health 2019, 16, 1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heise, L. Determinants of Partner Violence in Low and Middle-Income Countries: Exploring Varitation in Individual and Population-Level Risk. Ph.D. Thesis, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, A.; Dunkle, K.; Ramsoomar, L.; Willan, S.; Jama Shai, N.; Chatterji, S.; Naved, R.; Jewkes, R. New learnings on drivers of men’s physical and/or sexual violence against their female partners, and women’s experiences of this, and the implications for prevention interventions. Glob. Health Act. 2020, 13, 1739845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-León, N.C.; Peña, J.J.; Salazar, H.; García, A.; Sierra, J.C. A systematic review of romantic jealousy in relationships. Ter. Psicol. 2017, 32, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellsberg, M.; Peña, R.; Herrera, A.; Liljestrand, J.; Winkvist, A. Candies in hell: Women’s experiences of violence in Nicaragua. Soc. Sci. Med. 2000, 51, 1595–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gage, A.J. Women’s experience of intimate partner violence in Haiti. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 61, 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kar, H.L.; O’Leary, K.D. Patterns of psychological aggression, dominance, and jealousy within marriage. J. Fam. Violence 2013, 28, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Marco, A.; Soares, P.; Davó-Blanes, M.C.; Vives-Cases, C. Identifying types of dating violence and protective factors among adolescents in Spain: A qualitative analysis of Lights4Violence materials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health 2020, 17, 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fermani, A.; Bongelli, R.; Canestrari, C.; Muzi, M.; Riccioni, I.; Burro, R. “Old Wine in a New Bottle”. Depression and romantic telationships in Italian emerging adulthood: The moderating effect of gender. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health 2020, 17, 4121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fermani, A.; Bongelli, R.; Carrieri, A.; del Moral Arroyo, G.; Muzi, M.; Portelli, C. “What is more important than love?” Parental attachment and romantic relationship in Italian emerging adulthood. Cogent Psychol. 2019, 6, 1693728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnocky, S.; Sunderani, S.; Gomes, W.; Vaillancourt, T. Anticipated partner infidelity and men’s intimate partner violence: The mediating role of anxiety. Evolut. Behav. Sci. 2015, 9, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramsky, T.; Devries, K.M.; Michau, L.; Nakuti, J.; Musuya, T.; Kiss, L.; Kyegombe, N.; Watts, C. Ecological pathways to prevention: How does the SASA! Community mobilisation model work to prevent physical intimate partner violence against women? BMC Publ. Health 2016, 16, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buller, A.M.; Hidrobo, M.; Peterman, A.; Heise, L. The way to a man’s heart is through his stomach? A mixed methods study on causal mechanisms through which cash and in-kind food transfers decreased intimate partner violence. BMC Publ. Health 2016, 16, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, H.L.; Williams, L.R. “It’s not just you two”: A grounded theory of peer-influenced jealousy as a pathway to dating violence among acculturating Mexican American adolescents. Psychol. Violence 2014, 4, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattery, A. Intimate Partner Violence; Rowman & Littlefield: Lenham, MD, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Van derEnde, K.E.; Yount, K.M.; Dynes, M.M.; Sibley, L.M. Community-level correlates of intimate partner violence against women globally: A systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 1143–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Doherty, L.; Hegarty, K.; Ramsay, J.; Davidson, L.L.; Feder, G.; Taft, A. Screening women for intimate partner violence in healthcare settings. Cochrane Database Systematic Rev. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivas, C.; Ramsay, J.; Sadowski, L.; Davidson, L.L.; Dunne, D.; Eldridge, S.; Hegarty, K.; Taft, A.; Feder, G. Advocacy interventions to reduce or eliminate violence and promote the physical and psychosocial well-being of women who experience intimate partner abuse. Cochrane Database Systematic Rev. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagarin, B.J.; Martin, A.L.; Coutinho, S.A.; Edlund, J.E.; Patel, L.; Skowronski, J.J.; Zengel, B. Sex differences in jealousy: A meta-analytic examination. Evolut. Hum. Behav. 2012, 33, 595–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vossler, A. Internet infidelity 10 years on: A critical review of the literature. Fam. J. 2016, 24, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, P.C.; Kaufman, A.; Manning, W.D.; Longmore, M.A. Teen dating violence: The influence of friendships and school context. Sociol. Focus 2015, 48, 150–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coker, A.L.; Bush, H.M.; Brancato, C.J.; Clear, E.R.; Recktenwald, E.A. Bystander program effectiveness to reduce violence acceptance: RCT in high schools. J. Fam. Violence 2019, 34, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, P.C.; Copp, J.E.; Longmore, M.A.; Manning, W.D. Contested domains, verbal “amplifiers,” and intimate partner violence in young adulthood. Soc. Forc. 2015, 94, 923–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsangidou, M.; Otterbacher, J. Can posting be a catalyst for dating violence? Social media behaviors and physical interactions. Violence Gend. 2018, 5, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, V.R.; Khaw, L.B.L.; Bermea, A.; Hardesty, J.L. Future directions in intimate partner violence research: An intersectionality framework for analyzing women’s processes of leaving abusive relationships. J. Interpers. Violence 2020, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.C.; Webster, D.; Koziol-McLain, J.; Block, C.; Campbell, D.; Curry, M.A.; Gary, F.; Glass, N.; McFarlane, J.; Sachs, C.; et al. Risk factors for femicide in abusive relationships: Results from a multisite case control study. Am. J. Publ. Health 2003, 93, 1089–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleury, R.E.; Sullivan, C.M.; Bybee, D.I. When ending the relationship does not end the violence: Women’s experiences of violence by former partners. Violence Against Women 2000, 6, 1363–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, K.A. Women’s experience of violence during stalking by former romantic partners: Factors predictive of stalking violence. Violence Against Women 2005, 11, 89–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutton, D.G.; Van Ginkel, C.; Landolt, M.A. Jealousy, intimate abusiveness, and intrusiveness. J. Fam. Violence 1996, 11, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Nevado-Holgado, A.J.; Molero, Y.; D’Onofrio, B.M.; Larsson, H.; Howard, L.M.; Fazel, S. Mental disorders and intimate partner violence perpetrated by men towards women: A Swedish population-based longitudinal study. PLoS Med. 2019, 16, e1002995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingham, M.; Gordon, H. Aspects of morbid jealousy. Adv. Psychiatr. Treat. 2004, 10, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bair-Merritt, M.H.; Shea Crowne, S.; Thompson, D.A.; Sibinga, E.; Trent, M.; Campbell, J. Why do women use intimate partner violence? A systematic review of women’s motivations. Trauma Violence Abuse 2010, 11, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, E.C.; Herbenick, D.; Martinez, O.; Fu, T.C.; Dodge, B. Open relationships, nonconsensual nonmonogamy, and monogamy among, U.S. Adults: Findings from the 2012 national survey of sexual health and behavior. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2018, 47, 1439–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. The PRISMA group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, S.H.; Black, N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 1998, 52, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann. Int. Med. 2007, 147, 573–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). CASP Qualitative Checklist. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2019).

- Alan, H.; Yilmaz, S.D.; Filiz, E.; Arioz, A. Domestic violence awareness and prevention among married women in Central Anatolia. J. Fam. Violence 2016, 31, 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alan, H.; Koc, G.; Taskin, L.; Eroglu, K.; Terzioglu, F. Exposure of pregnant women to violence by partners and affecting factors in Turkey. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2016, 13, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansara, D.L.; Hindin, M.J. Perpetration of intimate partner aggression by men and women in the Philippines: Prevalence and associated factors. J. Interpers. Violence 2009, 24, 1579–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuemchit, M.; Chernkwanma, S.; Rugkua, R.; Daengthern, L.; Abdullakasim, P.; Wieringa, S.E. Prevalence of intimate partner violence in Thailand. J. Fam. Violence 2018, 33, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, A.A. Marital infidelity and intimate partner violence in rural Malawi: A dyadic investigation. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2014, 43, 1303–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelstein, A. Intimate partner jealousy and femicide among former Ethiopians in Israel. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2018, 62, 383–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, A.T.; Shackelford, T.K. Sexual coercion in intimate relationships: A comparative analysis of the effects of women’s infidelity and men’s dominance and control. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2009, 38, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham-Kevan, N.; Archer, J. Violence during pregnancy: Investigating infanticidal motives. J. Fam. Violence 2011, 26, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guay, S.; Sader, J.; Boisvert, J.M.; Beaudry, M. Typology of perceived causes of intimate partner violence perpetration in young adults. Violence Gend. 2016, 3, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalokhe, A.S.; Iyer, S.R.; Gadhe, K.; Katendra, T.; Paranjape, A.; Del Rio, C.; Stephenson, R.; Sahay, S. Correlates of domestic violence perpetration reporting among recently-married men residing in slums in Pune, India. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0197303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, D.C.R.; Capaldi, D.M. Young men’s intimate partner violence and relationship functioning: Long-term outcomes associated with suicide attempt and aggression in adolescence. Psychol. Med. 2011, 41, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaMotte, A.D.; Meis, L.A.; Winters, J.J.; Barry, R.A.; Murphy, C.M. Relationship problems among men in treatment for engaging in intimate partner violence. J. Fam. Violence 2018, 33, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, C.A.; Stith, S.M.; Thomsen, C.J.; McCollum, E.E. Violent couples seeking therapy: Bilateral and unilateral violence. Partn. Abuse 2012, 3, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, T.; Landwehr, J.; Lindquist, C.; Feinberg, R.; Comfort, M.; Cohen, J.; Bir, A. Intimate partner violence in couples navigating incarceration and reentry. J. Offender Rehabilit. 2018, 57, 273–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messing, J.T.; Thaller, J.; Bagwell, M. Factors related to sexual abuse and forced sex in a sample of women experiencing police-involved intimate partner violence. Health Soc. Work 2014, 39, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paat, Y.F.; Hope, T.L.; Mangadu, T.; Nunez-Mchiri, G.G.; Chavez-Baray, S.M. Family- and community-related determinants of intimate partner violence among Mexican and Puerto Rican origin mothers in fragile families. Womens Stud. Int. Forum 2017, 62, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salwen, J.K.; O’Leary, K.D. Adjustment problems and maladaptive relational style: A mediational model of sexual coercion in intimate relationships. J. Int. Violence 2013, 28, 1969–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, M.; Shrestha, S.; Shrestha, B. Domestic violence among antenatal attendees in a Kathmandu hospital and its associated factors: A cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016, 16, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Snead, A.L.; Babcock, J.C. Differential predictors of intimate partner sexual coercion versus physical assault perpetration. J. Sex. Aggress. 2019, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stieglitz, J.; Gurven, M.; Kaplan, H.; Winking, J. Infidelity, jealousy, and wife abuse among Tsimane forager-farmers: Testing evolutionary hypotheses of marital conflict. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2012, 33, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Stieglitz, J.; Kaplan, H.; Gurven, M.; Winking, J.; Tayo, B.V. Spousal violence and paternal disinvestment among Tsimane forager-horticulturalists. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2011, 23, 445–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toprak, S.; Ersoy, G. Femicide in Turkey between 2000 and 2010. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Townsend, L.; Jewkes, R.; Mathews, C.; Johnston, L.G.; Flisher, A.J.; Zembe, Y.; Chopra, M. HIV risk behaviours and their relationship to intimate partner violence (IPV) among men who have multiple female sexual partners in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2011, 15, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulibarri, M.D.; Strathdee, S.A.; Lozada, R.; Magis-Rodriguez, C.; Amaro, H.; O’Campo, P.; Patterson, T.L. Intimate partner violence among female sex workers in two Mexico-U.S. border cities: Partner characteristics and HIV risk behaviors as correlates of abuse. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2010, 2, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Parish, W.L.; Laumann, E.O.; Luo, Y. Partner violence and sexual jealousy in China: A population-based survey. Violence Against Women 2009, 15, 774–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. Countries and Economies. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/country (accessed on 26 May 2020).

- Sleath, E.; Walker, K.; Tramontano, C. Factor structure and validation of the controlling behaviors scale–revised and revised conflict tactics scale. J. Fam. Issues 2017, 39, 1880–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, S.M.; Wong, P.T.P. Multidimensional jealousy. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 1989, 6, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, G.L. A model of romantic jealousy. Motiv. Emot. 1981, 5, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, S.; Sala, A.C.; Candelaria, E.M.; Norman, L.R. Understanding the barriers that reduce the effectiveness of HIV/AIDS prevention strategies for Puerto Rican women living in low-income households in Ponce, PR: A qualitative study. J. Immigr. Minority Health 2010, 12, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Adinkrah, M. Intimate partner femicide-suicides in Ghana: Victims, offenders, and incident characteristics. Violence Against Women 2014, 20, 1078–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpanantikul, M. Disclosing middle-aged Thai women’s voices about unfaithful husbands. Pacific Rim Int. J. Nurs. Res. 2010, 14, 346–359. [Google Scholar]

- Bahadir-Yilmaz, E.; Oz, F. Experiences and perceptions of abused Turkish women regarding violence against women. Commun. Ment. Health J. 2019, 55, 686–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, M.J.; Kremelberg, D.; Dwivedi, P.; Verma, S.; Schensul, J.J.; Gupta, K.; Chandran, D.; Singh, S.K. The effects of husband’s alcohol consumption on married women in three low-income areas of greater Mumbai. AIDS Behav. 2010, 14, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boira, S.; Tomas-Aragones, L.; Rivera, N. Intimate partner violence and femicide in Ecuador. Qual. Soc. Rev. 2017, 13, 30–47. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce, S.; Zeledon, P.; Tellez, E.; Barrington, C. Gender-specific jealousy and infidelity norms as sources of sexual health risk and violence among young coupled Nicaraguans. Am. J. Publ. Health 2016, 106, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, S. What happens before intimate partner violence? Distal and proximal antecedents. J. Fam. Violence 2012, 27, 783–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, A.A.; McKenna, S.A.; Comfort, M.L.; Darbes, L.A.; Tan, J.Y.; Mkandawire, J. Marital infidelity, food insecurity, and couple instability: A web of challenges for dyadic coordination around antiretroviral therapy. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 214, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, A.A.; McKenna, S.A.; Ruark, A. Couple interdependence impacts alcohol use and adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Malawi. AIDS Behav. 2019, 23, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, T.K.; Bhattacharyya, R.; Alam, M.F.; Pervin, A. Domestic violence in Sylhet, Bangladesh: Analysing the experiences of abused women. Soc. Change 2016, 46, 106–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenton, B.; Rathus, J.H. Men’s self-reported descriptions and precipitants of domestic violence perpetration as reported in intake evaluations. J. Fam. Violence 2010, 25, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freysteinsdóttir, F.J. The different dynamics of femicide in a small Nordic welfare society. Prz. Socjol. Jakosciowej 2017, 13, 14–28. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, A.; Sikweyiya, Y.; Jewkes, R. “Men value their dignity”: Securing respect and identity construction in urban informal settlements in South Africa. Glob. Health Act. 2014, 7, 23676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guruge, S.; Ford-Gilboe, M.; Varcoe, C.; Jayasuriya-Illesinghe, V.; Ganesan, M.; Sivayogan, S.; Kanthasamy, P.; Shanmugalingam, P.; Vithanarachchi, H. Intimate partner violence in the post-war context: Women’s experiences and community leaders perceptions in the eastern province of Sri Lanka. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatcher, A.; Stöckl, H.; Christofides, N.; Woollett, N.; Pallitto, C.; Garcia-Moreno, C.; Turan, J. Mechanisms linking intimate partner violence and prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV: A qualitative study in South Africa. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 168, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyegombe, N.; Starmann, E.; Devries, K.M.; Michau, L.; Nakuti, J.; Musuya, T.; Watts, C.; Heise, L. “SASA! is the medicine that treats violence”. Qualitative findings on how a community mobilisation intervention to prevent violence against women created change in Kampala, Uganda. Glob. Health Act. 2014, 7, 25082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, J.M.; Bonomi, A.E.; Lee, M.A.; Ludwin, J.M. Sexual infidelity as trigger for intimate partner violence. J. Women Health 2012, 21, 942–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhi, T.T.; Hanh, N.T.T.; Gammeltoft, T.M. Emotional violence and maternal mental health: A qualitative study among women in northern Vietnam. BMC Womens Health 2018, 18, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nudelman, A.; Boira, S.; Tina, T.; Balica, E.; Tabagua, S. “Hearing their voices”: Exploring femicide among migrants and culture minorities. Qual. Soc. Rev. 2017, 13, 48–68. [Google Scholar]

- Nur Hayati, E.; Eriksson, M.; Hakimi, M.; Högberg, U.; Emmelin, M. “Elastic band strategy”: Women’s lived experience of coping with domestic violence in rural Indonesia. Glob. Health Action 2013, 6, 18894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orengo-Aguayo, R.E.M.A.; Lawrence, E.P. Missing the trees for the forest: Understanding aggression among physically victimized women. Partn. Abuse 2014, 5, 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paixão, G.P.; Gomes, N.P.; Diniz, N.M.F.; Couto, T.M.; Vianna, L.A.C.; Santos, S.M.P. Situations which precipitate conflicts in the conjugal relationship: The women’s discourse. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2014, 23, 1041–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Starmann, E.; Collumbien, M.; Kyegombe, N.; Devries, K.; Michau, L.; Musuya, T.; Watts, C.; Heise, L. Exploring couples processes of change in the context of SASA!, a violence against women and HIV prevention intervention in Uganda. Prev. Sci. 2017, 18, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stith, S.M.; Amanor-Boadu, Y.; Miller, M.S.; Menhusen, E.; Morgan, C.; Few-Demo, A. Vulnerabilities, stressors, and adaptations in situationally violent relationships. Fam. Relat. 2011, 60, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, D.S.; Chandra, P.S.; Callahan, C.; Reich, W.; Cottler, L.B. Perceptions of HIV risk among monogamous wives of alcoholic men in South India: A qualitative study. J. Women Health 2010, 19, 815–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byers, E.S. How well does the traditional sexual script explain sexual coercion? J. Psychol. Hum. Sex. 1996, 8, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.S.; Fischer, A.R. Does entitlement mediate the link between masculinity and rape-related variables? J. Couns. Psychol. 2001, 48, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, E.; Heise, L. Sexual coercion, consent and negotiation: Processes of change amongst couples participating in the Indashyikirwa programme in Rwanda. C. Health Sex. 2019, 21, 867–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, R.W.; Messerschmidt, J.W. Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gend. Soc. 2005, 19, 829–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haavio-Mannila, E.; Kontula, O. Single and double sexual standards in Finland, Estonia, and St. Petersburg. J. Sex Res. 2003, 40, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schippers, M. Recovering the feminine other: Masculinity, femininity, and gender hegemony. Theory Soc. 2007, 36, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, E.; Buikema, R. The relational dynamics of hegemonic masculinity among South African men and women in the context of HIV. Cult. Health Sex. 2013, 15, 1040–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Coggins, M.; Bullock, L.F. The wavering line in the sand: The effects of domestic violence and sexual coercion. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2003, 24, 723–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dworkin, S.L.; Treves-Kagan, S.; Lippman, S.A. Gender-transformative interventions to reduce HIV risks and violence with heterosexually-active men: A review of the global evidence. AIDS Behav. 2013, 17, 2845–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casey, E.; Carlson, J.; Two Bulls, S.; Yager, A. Gender transformative approaches to engaging men in gender-based violence prevention: A review and conceptual model. Trauma Violence Abus. 2018, 19, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacPhail, C.; Khoza, N.; Treves-Kagan, S.; Selin, A.; Gómez-Olivé, X.; Peacock, D.; Rebombo, D.; Twine, R.; Maman, S.; Kahn, K.; et al. Process elements contributing to community mobilization for HIV risk reduction and gender equality in rural South Africa. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander-Scott, M.; Bell, E.; Holden, J. DFID Guidance Note: Shifting Social Norms to Tackle Violence Against Women and Girls (VAWG); VAWG Helpdesk: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Crepaz, N.; Tungol-Ashmon, M.V.; Vosburgh, H.W.; Baack, B.N.; Mullins, M.M. Are couple-based interventions more effective than interventions delivered to individuals in promoting HIV protective behaviors? A meta-analysis. AIDS Care 2015, 27, 1361–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babcock, J.C.; Armenti, N.A.; Warford, P. The trials and tribulations of testing couples-based interventions for intimate partner violence. Partn. Abuse 2017, 8, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkle, K.; Stern, E.; Heise, L.; McLean, L.; Chatterji, S. Impact of Indashyikirwa: An innovative programme to reduce partner violence in rural Rwanda. Unpublished work. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Treves-Kagan, S.; Maman, S.; Khoza, N.; MacPhail, C.; Peacock, D.; Twine, R.; Kahn, K.; Lippman, S.A.; Pettifor, A. Fostering gender equality and alternatives to violence: Perspectives on a gender-transformative community mobilisation programme in rural South Africa. Cult. Health Sex. 2019, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, K.E.; Quigley, B.M. Thirty years of research show alcohol to be a cause of intimate partner violence: Future research needs to identify who to treat and how to treat them. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2017, 36, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, I.M.; Graham, K.; Taft, A. Alcohol interventions, alcohol policy and intimate partner violence: A systematic review. BMC Publ. Health 2014, 14, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, B.; Famoye, F. Domestic violence against women, and their economic dependence: A count data analysis. Rev. Pol. Econ. 2004, 16, 457–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougal, L.; Klugman, J.; Dehingia, N.; Trivedi, A.; Raj, A. Financial inclusion and intimate partner violence: What does the evidence suggest? PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heise, L.; Kotsadam, A. Cross-National and multilevel correlates of partner violence: An analysis of data from population-based surveys. Lancet Glob. Health 2015, 3, e332–e340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, G.T. Dying to be Men: Youth, Masculinity and Social Exclusion; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, E.; Gibbs, A.; Willan, S.; Dunkle, K.; Jewkes, R. “When you talk to someone in a bad way or always put her under pressure, it is actually worse than beating her”: Conceptions and experiences of emotional intimate partner violence in Rwanda and South Africa. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buller, A.M.; Peterman, A.; Ranganathan, M.; Bleile, A.; Hidrobo, M.; Heise, L. A mixed-method review of cash transfers and intimate partner violence in low- and middle-income countries. World Bank Res. Obs. 2018, 33, 218–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan, M.; Knight, L.; Abramsky, T.; Muvhango, L.; Polzer Ngwato, T.; Mbobelatsi, M.; Ferrari, G.; Watts, C.; Stöckl, H. Associations between women’s economic and social empowerment and intimate partner violence: Findings from a microfinance plus program in rural north west province, South Africa. J. Interpers. Violence 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scelza, B.A.; Prall, S.P.; Blumenfield, T.; Crittenden, A.N.; Gurven, M.; Kline, M.; Koster, J.; Kushnick, G.; Mattison, S.M.; Pillsworth, E.; et al. Patterns of paternal investment predict cross-cultural variation in jealous response. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardinha, L.; Nájera Catalán, H.E. Attitudes towards domestic violence in 49 low- and middle-income countries: A gendered analysis of prevalence and country-level correlates. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, C.M.; Hoover, S.A. Measuring emotional abuse in dating relationships as a multifactorial construct. Violence Vict. 1999, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buller, A.M.; Pichon, M.; McAlpine, A.; Cislaghi, B.; Heise, L.; Meiksin, R. Systematic review of social norms, attitudes, and factual beliefs linked to the sexual exploitation of children and adolescents. Child Abuse Negl. 2020, 104, 104471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marston, C.; King, E. Factors that shape young people’s sexual behaviour: A systematic review. Lancet 2006, 368, 1581–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Criteria | Included | Excluded | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sampling | Adults (aged 18+) in current heterosexual relationships. | Students, people with diagnosed medical conditions. | Association between infidelity and RJ, and IPV may differ in:

|

| Infidelity or romantic jealousy (RJ) outcome | Quantitative: Prevalence of, or measure of association between, infidelity or RJ and male-to-female IPV. | Infidelity or RJ as part of bigger variable without disaggregates, proxy’s such as “polygamy”. |

|

| Intimate partner violence (IPV) outcome | Qualitative: Evidence of pathway between infidelity or RJ and male-to-female IPV. | Predicted or feared IPV. |

| Author (Year) | Country | Sample Size | Quality 1 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alan et al. (2016a) | Turkey | 1039 | ★☆☆☆ | [49] |

| Alan et al. (2016b) | Turkey | 442 | ★☆☆☆ | [50] |

| Ansara and Hindin (2009) | Philippines | 1861 | ★★★★ | [51] |

| Chuemchit et al. (2018) | Thailand | 2462 | ★★★☆ | [52] |

| Conroy (2014) | Malawi | 422 | ★★★☆ | [53] |

| Edelstein (2018) | Israel | 194 | ★★★☆ | [54] |

| Goetz and Shackelford (2009) | USA | 546 | ★★☆☆ | [55] |

| Graham-Kevan and Archer (2011) | UK | 43 | ★☆☆☆ | [56] |

| Guay et al. (2016) | Canada | 466 | ★★☆☆ | [57] |

| Kalokhe et al. (2018) | India | 100 | ★★☆☆ | [58] |

| Kerr and Capaldi (2011) | USA | 153 | ★★★☆ | [59] |

| LaMotte et al. (2018) | USA | 589 | ★★★☆ | [60] |

| Madsen et al. (2012) | USA | 258 | ★★☆☆ | [61] |

| McKay et al. (2018) | USA | 1332 | ★★☆☆ | [62] |

| Messing et al. (2014) | USA | 432 | ★★☆☆ | [63] |

| Paat et al. (2017) | USA | 5000 | ★★★☆ | [64] |

| Salwen and O’Leary (2013) | USA | 830 | ★★★★ | [65] |

| Shrestha et al. (2016) | Nepal | 404 | ★★☆☆ | [66] |

| Snead et al. (2019) | USA | 318 | ★★☆☆ | [67] |

| Stieglitz et al. (2011) | Bolivia | 49 | ★★☆☆ | [68] |

| Stieglitz et al. (2012) | Bolivia | 266 2 | ★☆☆☆ | [69] |

| Toprak and Ersoy (2017) | Turkey | 162 | ★★☆☆ | [70] |

| Townsend et al. (2011) | South Africa | 428 | ★☆☆☆ | [71] |

| Ulibarri et al. (2010) | Mexico | 300 | ★☆☆☆ | [72] |

| Wang et al. (2009) | China | 2661 | ★★☆☆ | [73] |

| Characteristics and Findings | No. Studies (%) | Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Region1 | ||

| East Asia and Pacific | 3 (12) | [51,52,73] |

| Europe and Central Asia | 4 (16) | [49,50,56,70] |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 3 (12) | [68,69,72] |

| Middle East and North Africa | 1 (4) | [54] |

| North America | 10 (40) | [55,57,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,67] |

| South Asia | 2 (8) | [58,66] |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 2 (8) | [53,71] |

| Study Design | ||

| Cross-sectional | 22 (88) | [49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,59,60,61,63,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73] |

| Longitudinal-Cohort | 3 (12) | [58,62,64] |

| Infidelity or RJ Measurement Instrument | ||

| Validated questionnaire or scale | 8 (32) | [52,57,58,60,61,62,65,67] |

| Continuous or Likert scale question | 4 (16) | [53,55,56,68] |

| Multiple choice or binary question | 7 (28) | [51,63,64,66,71,72,73] |

| Open-ended question | 3 (12) | [49,50,69] |

| Observational | 2 (8) | [54,70] |

| Mix | 1 (4) | [59] |

| Infidelity or RJ Outcome * | ||

| F suspicion of M infidelity | 4 | [53,62,64,66] |

| M suspicion of F infidelity | 5 | [52,53,55,62,71] |

| Real F infidelity | 2 | [53,55] |

| Real M infidelity | 7 | [53,55,58,66,68,71,72] |

| F romantic jealousy | 6 | [57,60,61,62,65,73] |

| M romantic jealousy | 12 | [51,52,56,57,58,60,61,62,63,65,67,73] |

| Romantic jealousy not specified | 1 | [59] |

| All (open-ended/observational) | 5 | [49,50,54,69,70] |

| IPV Measurement Instrument | ||

| Conflict Tactics Scale or adaption | 9 (36) | [51,56,57,60,61,62,63,65,67] |

| Other scale (e.g., Sexual Coercion in Intimate Relationships Scale) | 4 (16) | [55,58,64,72] |

| Inventory of specific behaviours (e.g., pushed or shoved) | 6 (24) | [49,50,52,66,71,73] |

| General items (e.g., experience of “violence” or “assault”) | 4 (16) | [53,59,68,69] |

| Intimate partner homicide | 2 (8) | [54,70] |

| IPV Outcome | ||

| Physical only | 8 (32) | [54,56,59,64,68,69,70,73] |

| Sexual only | 3 (12) | [55,65,67] |

| Psychological only | 0 | |

| Economic only | 0 | |

| Physical or sexual | 3 (12) | [53,62,71] |

| Physical or psychological | 3 (12) | [57,60,61] |

| Physical, sexual, or psychological | 6 (24) | [51,52,58,63,66,72] |

| Physical, sexual, psychological or economic | 2 (8) | [49,50] |

| IPV Outcome Reporter | ||

| Female self-report | 15 (60) | [49,50,51,52,56,59,61,62,63,64,66,67,68,69,72] |

| Male self-report | 3 (12) | [58,60,71] |

| Couple report | 5 (20) | [53,55,57,65,73] |

| Observation (e.g., review of court data) | 2 (8) | [54,70] |

| Analysis Type * | ||

| Prevalence (univariate) | 12 | [49,50,51,54,56,57,60,61,66,67,70,72] |

| Unadjusted or bivariate | 10 | [52,55,56,57,58,60,61,65,66,72] |

| Adjusted or multivariate | 14 | [51,53,58,59,62,63,64,66,67,68,69,71,72,73] |

| Infidelity or RJ and IPV Association * | ||

| Infidelity or RJ decreased IPV | 0 | |

| Infidelity or RJ increased IPV | 19 | [51,52,53,55,56,58,59,60,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,71,72,73] |

| Not associated | 5 | [53,62,63,64,71] |

| Mechanisms Described by Authors to Explain Findings * | ||

| Evolutionary or biological | 5 | [55,56,67,68,69] |

| Lack of emotional regulation and conflict resolution skills | 7 | [57,59,60,61,62,65,73] |

| Patriarchal culture | 9 | [49,50,55,60,64,66,70,71,72] |

| Threatened masculinities | 4 | [53,54,58,62] |

| None given | 3 | [51,52,63] |

| Author (Year) | Country | Sample Size | Type of IPV | Quality 1 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abreu et al. (2010) | Puerto Rico | 39 | Physical, sexual | ★★★☆ | [78] |

| Adinkrah (2014) | Ghana | 35 | Physical (femicide) | ★★☆☆ | [79] |

| Arpanantikul (2010) | Thailand | 18 | Physical, psychological, economic | ★★★★ | [80] |

| Bahadir-Yilmaz and Oz (2019) | Turkey | 30 | Physical, sexual | ★☆☆☆ | [81] |

| Berg et al. (2010) | India | 44 | Physical, psychological, economic | ★★★☆ | [82] |

| Boira et al. (2017) | Ecuador | 61 | Physical | ★☆☆☆ | [83] |

| Boyce et al. (2016) | Nicaragua | 30 | Physical, sexual, psychological | ★★★☆ | [84] |

| Byun (2012) | USA | ~95 2 | Physical | ★☆☆☆ | [85] |

| Conroy et al. (2018) † | Malawi | 50 | Physical, economic | ★★★☆ | [86] |

| Conroy et al. (2019) † | Malawi | 50 | Physical | ★★★☆ | [87] |

| Das et al. (2016) | Bangladesh | 42 | Physical, sexual, psychological | ★★☆☆ | [88] |

| Fenton and Rathus (2009) | USA | 24 | Physical, psychological | ★★☆☆ | [89] |

| Freysteinsdóttir (2017) | Iceland | 11 | Physical (femicide) | ★★★☆ | [90] |

| Gibbs et al. (2014) | South Africa | ~63 3 | Physical | ★★★☆ | [91] |

| Guruge et al. (2017) | Sri Lanka | 30 4 | Physical, psychological, economic | ★★★☆ | [92] |

| Hatcher et al. (2016) | South Africa | 32 | Physical, psychological | ★★★★ | [93] |

| Kyegombe et al. (2014) | Uganda | 40 | Economic | ★★★★ | [94] |

| Nemeth et al. (2012) | USA | 34 | Physical | ★★★☆ | [95] |

| Nhi et al. (2018) | Vietnam | 20 | Psychological | ★★★★ | [96] |

| Nudelman et al. (2017) | Georgia, Romania, Spain 5 | 10 6 | Physical | ★★★☆ | [97] |

| Nur Hayati et al. (2013) | Indonesia | 7 | Physical, psychological, economic | ★★★☆ | [98] |

| Orengo-Aguayo and Lawrence (2014) | USA | 40 | Physical, psychological | ★★★★ | [99] |

| Paixão et al. (2014) | Brazil | 19 | Physical, psychological | ★★☆☆ | [100] |

| Starmann et al. (2017) | Uganda | 20 | Sexual, psychological | ★★★☆ | [101] |

| Stith et al. (2011) | USA | 22 | Physical, psychological | ★★★☆ | [102] |

| Varma et al. (2010) | India | 14 | Physical, sexual, psychological | ★★★☆ | [103] |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pichon, M.; Treves-Kagan, S.; Stern, E.; Kyegombe, N.; Stöckl, H.; Buller, A.M. A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review: Infidelity, Romantic Jealousy and Intimate Partner Violence against Women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5682. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165682

Pichon M, Treves-Kagan S, Stern E, Kyegombe N, Stöckl H, Buller AM. A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review: Infidelity, Romantic Jealousy and Intimate Partner Violence against Women. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(16):5682. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165682

Chicago/Turabian StylePichon, Marjorie, Sarah Treves-Kagan, Erin Stern, Nambusi Kyegombe, Heidi Stöckl, and Ana Maria Buller. 2020. "A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review: Infidelity, Romantic Jealousy and Intimate Partner Violence against Women" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 16: 5682. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165682

APA StylePichon, M., Treves-Kagan, S., Stern, E., Kyegombe, N., Stöckl, H., & Buller, A. M. (2020). A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review: Infidelity, Romantic Jealousy and Intimate Partner Violence against Women. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(16), 5682. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165682