Designing ICTs for Users with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Usability Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Demographic Changes and Mild Cognitive Impairment

1.2. Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) and Cognitive Decline

2. Materials and Methods

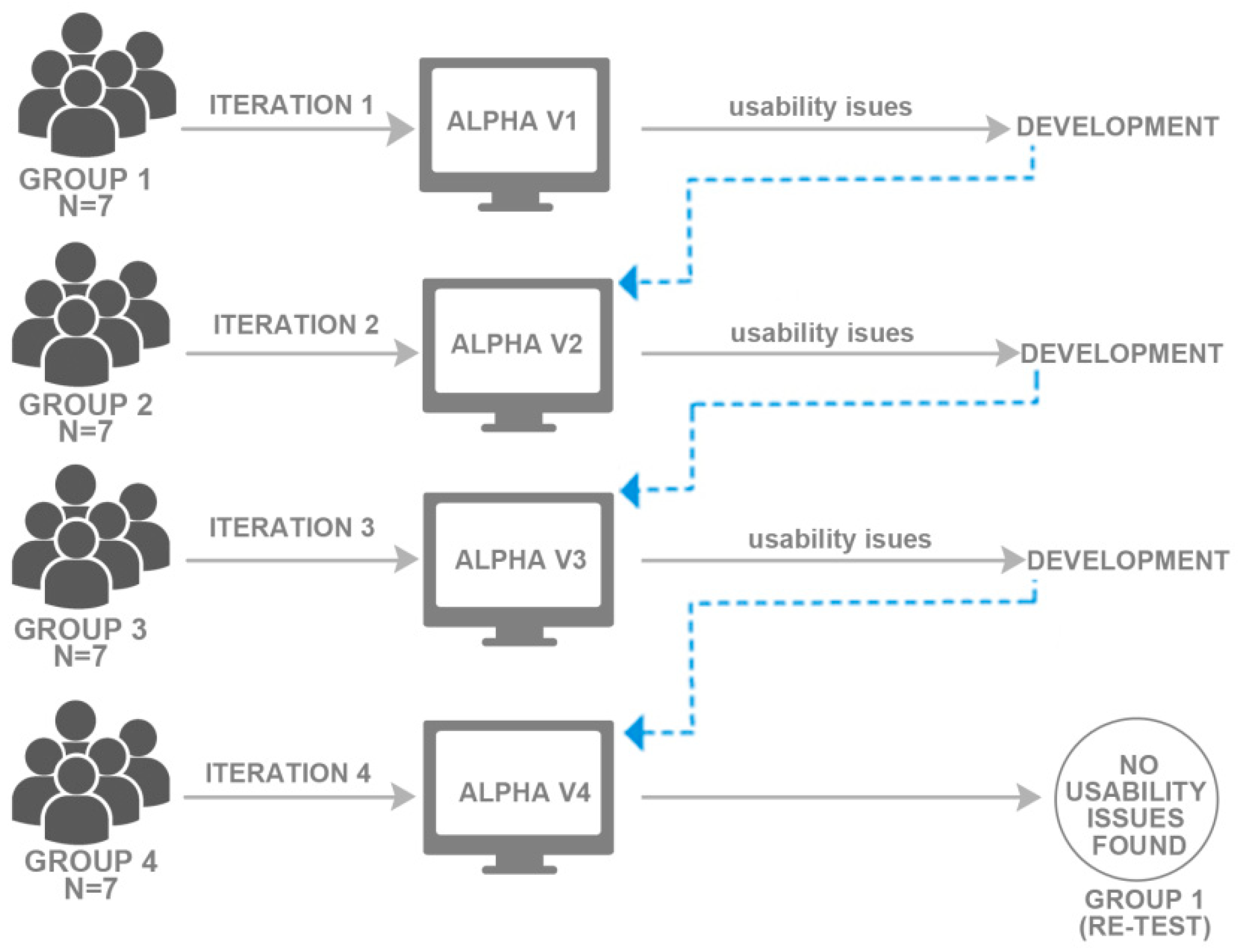

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Materials

2.3.1. Main Software

2.3.2. Variables and Measuring Instruments

User Profile

Measures Based on User Performance

Instruments Measuring the User’s Opinion

Measures Regarding Professional’s Judgment

2.3.3. Hardware

2.3.4. Statistical Software

2.4. Procedure

3. Results

3.1. Main Usability Findings

3.1.1. Solved through Behavior Program Changes

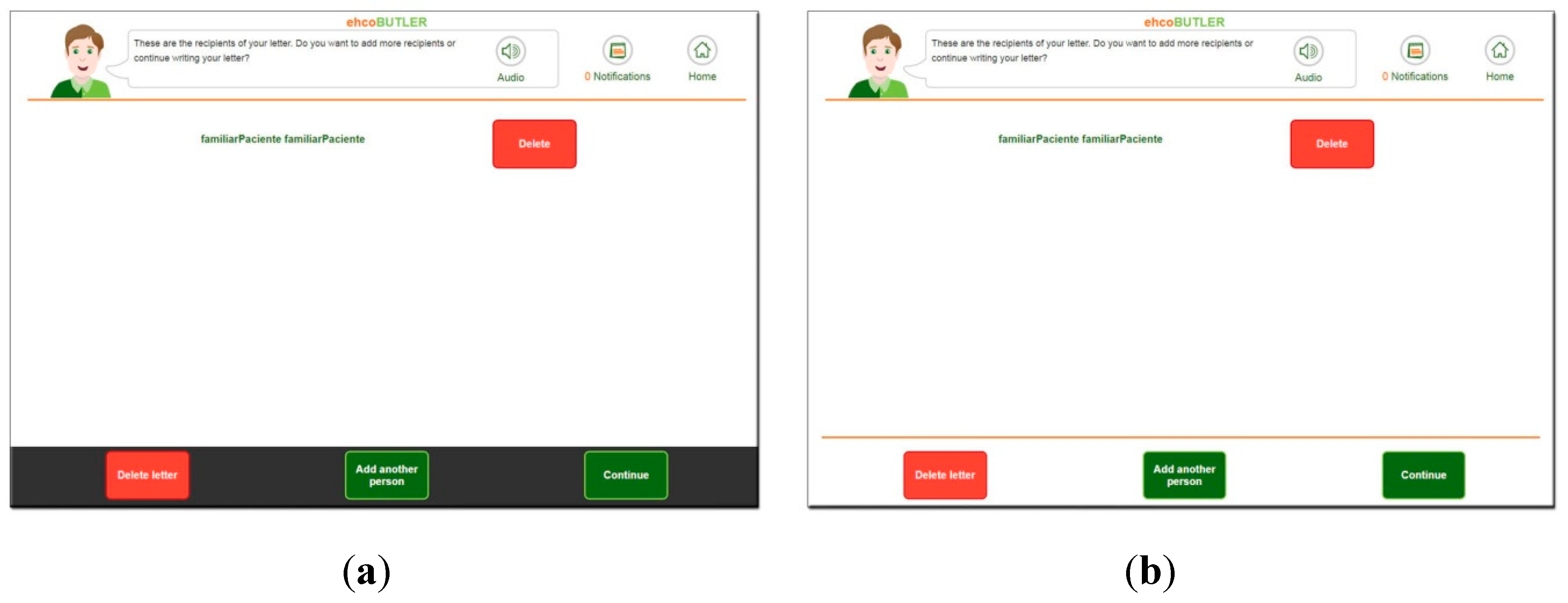

3.1.2. Solved through Graphical Changes

3.2. Quantitative Results

3.2.1. Task Performance

3.2.2. Number of Attempts

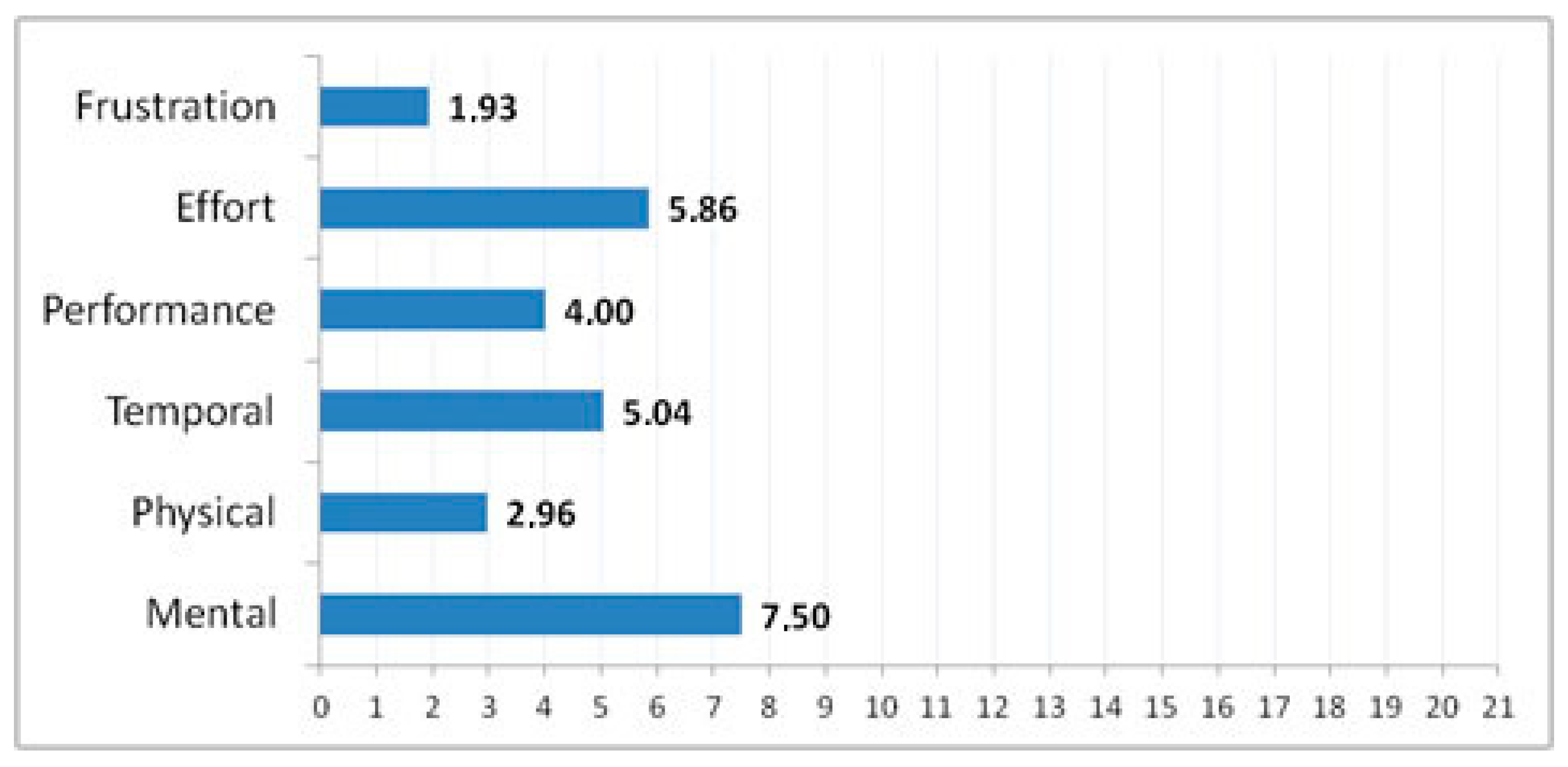

3.2.3. Workload NASA Task Work Load Index)

3.3. Quantitative Results

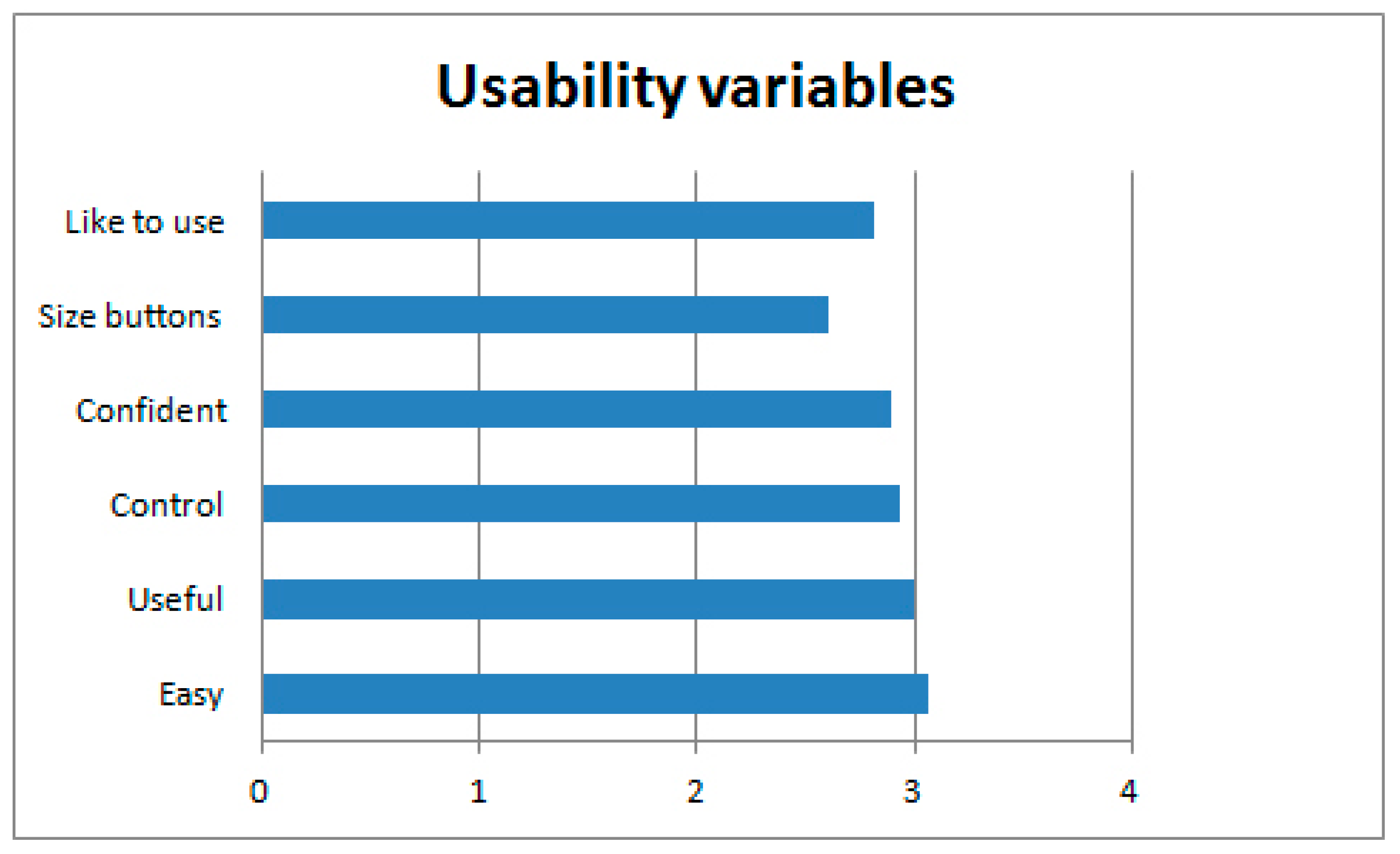

3.3.1. Usability Variables and User Opinion

3.3.2. Intention to Use

3.3.3. Preferences about Avatar Appearance and Voice

3.4. Professional Opinion

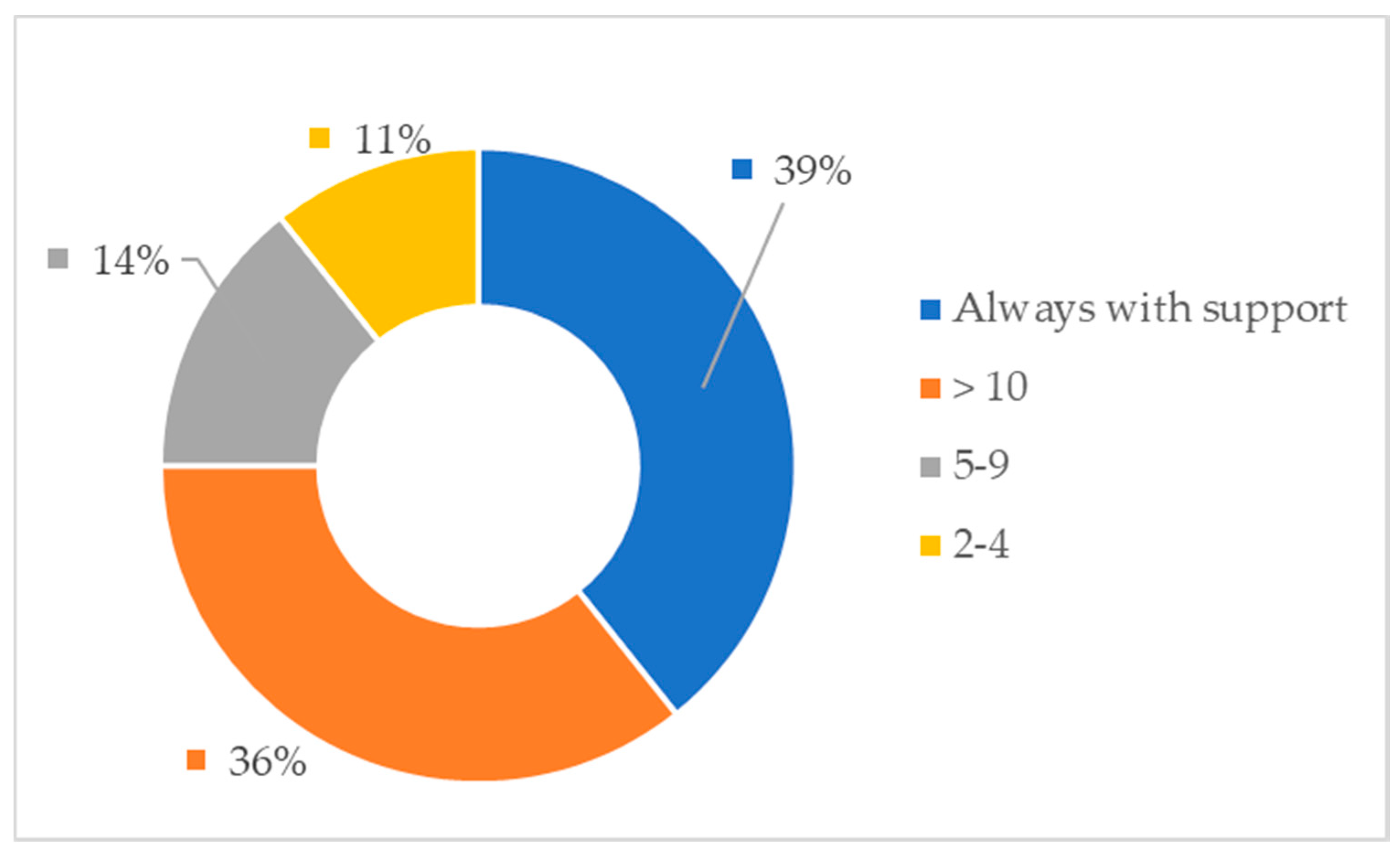

3.4.1. Ability to Use the System in an Autonomous Way

3.4.2. Sessions Needed to Learn to Use the System in an Unassisted Manner

3.4.3. Professional Opinion about the Users’ Feelings

4. Discussion

- Related to spatial abilities and attention. The results showed a low perception of peripheral elements and the need to place the main interaction elements (e.g., continue the action in the step-by-step navigation) in the center of the screen because less autonomous users showed an attentional focus on this central part of the screen and attentional blindness to the peripheral graphical elements.

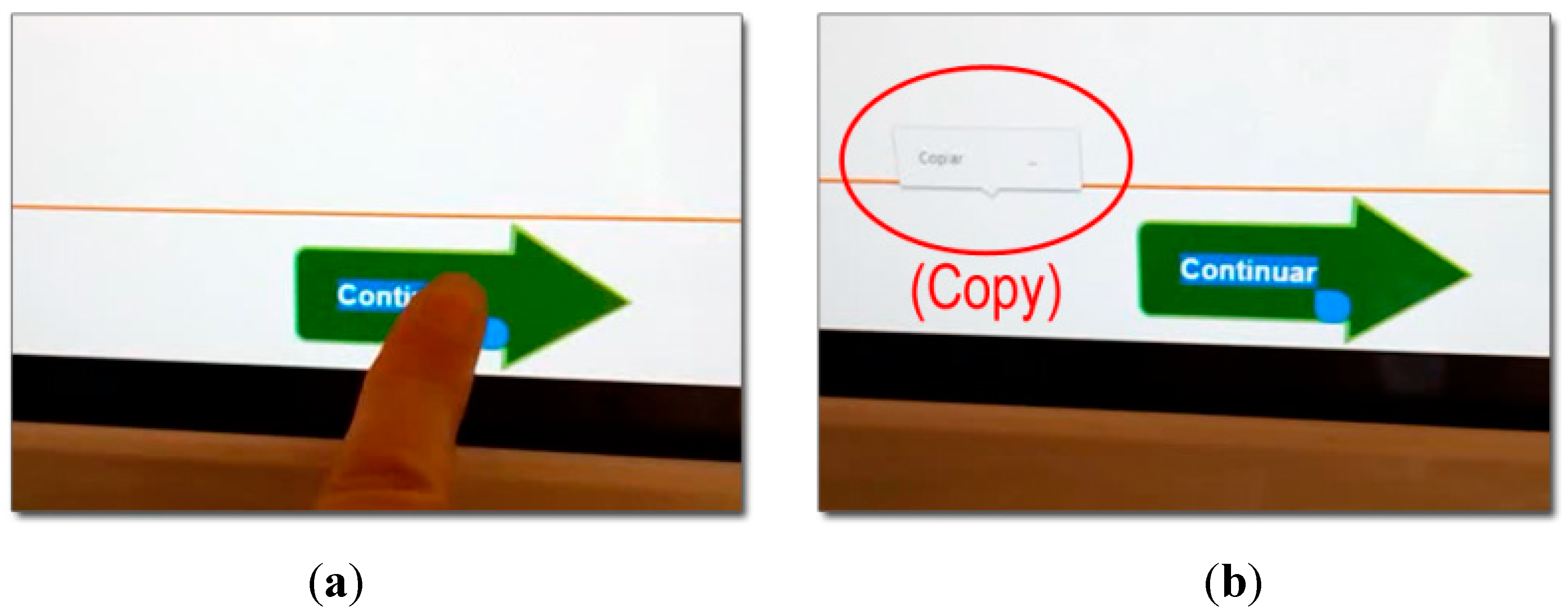

- Related programming interaction. Given that users expect a real time change in buttons (such as sinking down when pressed), the interaction with the buttons was performed by pressing them for a long time, causing an unexpected interaction result (copying text or activating the secondary browser menu). On the other hand, we observed the user’s need to see what they were pressing while touching the buttons. This explains why they clicked outside the buttons.

- Related audio help. The standard speed of synthetic speech (3 words per second) was too fast, and most of the users were not able to follow the instructions.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| ID | Number of Iteration | Cognitive Diagnosis | Age | Sex | School-Leaving Age | PC Experience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | MCI | 73 | M | 12 | Never |

| 2 | 1 | MCI | 83 | F | 10 | Never |

| 3 | 1 | MCI | 85 | M | Didn’t remember | Never |

| 4 | 1 | MCI | 71 | F | 14 | Never |

| 5 | 1 | MCI | 94 | M | 14 | Never |

| 6 | 1 | MCI | 88 | M | 10 | Never |

| 7 | 1 | MCI | 95 | F | 10 | Never |

| 8 | 2 | MCI | 67 | M | 14 | Never |

| 9 | 2 | MCI | 58 | M | 13 | Once |

| 10 | 2 | MCI | 89 | F | 8 | Never |

| 11 | 2 | MCI | 90 | F | 14 | Never |

| 12 | 2 | MCI | 86 | F | Didn’t go to school | Never |

| 13 | 2 | MCI | 89 | M | Didn’t go to school | Never |

| 14 | 2 | MCI | 85 | F | Didn’t go to school | Never |

| 15 | 3 | MCI | 76 | F | 8 | Never |

| 16 | 3 | MCI | 70 | M | 14 | Never |

| 17 | 3 | MCI | 85 | M | 7 | Never |

| 18 | 3 | MCI | 71 | F | 13 | Never |

| 19 | 3 | MCI | 69 | M | 15 | Never |

| 20 | 3 | MCI | 75 | M | Didn’t remember | More than 10 |

| 21 | 3 | MCI | 76 | M | 14 | From 1 to 10 |

| 22 | 4 | MCI | 81 | M | 12 | Never |

| 23 | 4 | MCI | 70 | F | 16 | More than 10 |

| 24 | 4 | MCI | 88 | F | 12 | Never |

| 25 | 4 | MCI | 67 | M | 20 | From 1 to 10 |

| 26 | 4 | MCI | 81 | F | 18 | Never |

| 27 | 4 | MCI | 91 | F | 11 | Never |

| 28 | 4 | MCI | 78 | F | 14 | Never |

References

- He, W.; Goodkind, D.; Kowal, P. An Aging World: 2015 International Population Reports. In U.S. Census Bureau, International Population Reports, P95/16-1, An Aging World 2015; US Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; p. 204. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Governments Commit to Advancements in Dementia Research and Care. Geneva. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2015/action-on-dementia/en/ (accessed on 25 November 2017).

- Fischer, P.; Jungwirth, S.; Zehetmayer, S.; Weissgram, S.; Hoenigschnabl, S.; Gelpi, E.; Tragl, K.H. Conversion from subtypes of mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer dementia. Neurology 2007, 68, 288–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, M.; Clare, L.; Altgassen, A.M.; Cameron, M.H.; Zehnder, F. Cognition-based interventions for healthy older people and people with mild cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, 19, CD006220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brum, P.S.; Forlenza, O.V.; Yassuda, M.S. Treino cognitivo em idosos com Comprometimento Cognitivo Leve: Impacto no desempenho cognitivo e funcional. Dement. e Neuropsychol. 2009, 3, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.Y.; Li, L.; Xiao, J.Q.; He, C.Z.; Lyu, X.L.; Gao, L.; Yang, X.W.; Cui, X.G.; Fan, L.H. Cognitive training in older adults with mild cognitive impairment. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2016, 29, 356–364. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Huntley, J.; Bhome, R.; Holmes, B.; Cahill, J.; Gould, R.L.; Wang, H.; Yu, X.; Howard, R. Effect of computerised cognitive training on cognitive outcomes in mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e027062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, H.; Traynor, V.; Solowij, N. Computerized and virtual reality cognitive training for individuals at high risk of cognitive decline: Systematic review of the literature. Am. J. Geriatr. 2015, 23, 335–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, M.; Jones, K.; Woods, B.; Gómez, P. Gradior: A personalized computer-based cognitive training programme for early intervention in dementia. In Early Psychosocial Interventions in Dementia. Evidence-Based Practice; Moniz-Cook, E., Manthorpe, J., Eds.; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- García-Betances, R.I.; Jiménez-Mixco, V.; Arredondo, M.T.; Cabrera-Umpiérrez, M.F. Using virtual reality for cognitive training of the elderly. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Demen. 2015, 30, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palau, F.; Franco, M.; Bamidis, P.; Losada, R.; Parra, E.; Papageorgiou, S.; Vivas, A.B. The effects of a computer-based cognitive and physical training program in a healthy and mildly cognitive impaired aging sample. Aging Ment. Health 2014, 18, 838–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuchat, J.; Ouellet, É.; Moffat, N.; Belleville, S. Opportunities for virtual reality in cognitive training with persons with mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease. Nonpharmacol. Ther. Dement. 2012, 3, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Baecker, R.M.; Marziali, E.; Chatland, S.; Easley, K.; Crete, M.; Yeung, M. Multimedia biographies for individuals with Alzheimer’s disease and their families. In Proceedings of the World Congress on Internet in Medicine, Toronto, ON, Canada, 14–19 October 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Barban, F.; Annicchiarico, R.; Pantelopoulos, S.; Federici, A.; Perri, R.; Fadda, L.; Carlesimo, G.A.; Ricci, C.; Giuli, S.; Scalici, F.; et al. Protecting cognition from aging and Alzheimer’s disease: A computerized cognitive training combined with reminiscence therapy. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2015, 31, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damianakis, T.; Crete-Nishihata, M.; Smith, K.L.; Baecker, R.M.; Marziali, E. The psychosocial impacts of multimedia biographies on persons with cognitive impairments. Gerontologist 2010, 50, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino, M.; Boulay, M.; Jouen, F.; Rigaud, A.S. “Are we ready for robots that care for us?” Attitudes and opinions of older adults toward socially assistive robots. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2015, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornejo, R.; Tentori, M.; Favela, J. Enriching in-person encounters through social media: A study on family connectedness for the elderly. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2013, 71, 889–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, P.; Rezvani, A.; Wiewiora, A. The impact of technology on older adults’ social isolation. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 63, 594–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, L.A.; Ziser, S.; Spector, A.; Orrell, M. Cognitive leisure activities and future risk of cognitive impairment and dementia: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2016, 28, 1791–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazar, A.; Thompson, H.; Demiris, G. A systematic review of the use of technology for reminiscence therapy. Health Educ. Behav. 2014, 41, 51S–61S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preschl, B.; Maercker, A.; Wagner, B.; Forstmeier, S.; Baños, R.M.; Alcañiz, M.; Castilla, D.; Botella, C. Life-review therapy with computer supplements for depression in the elderly: A randomized controlled trial. Aging Ment. Health 2012, 16, 964–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, A.; Hamer, M.; McMunn, A.; Steptoe, A. Social isolation and loneliness: Relationships with cognitive function during 4 years of follow-up in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Psychosom. Med. 2013, 75, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; He, P.; Dong, B. Associations between social networks, social contacts, and cognitive function among Chinese nonagenarians/centenarians. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2015, 60, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.S.; Boyle, P.A.; James, B.D.; Leurgans, S.E.; Buchman, A.S.; Bennett, D.A. Negative social interactions and risk of mild cognitive impairment in old age. Neuropsychology 2015, 29, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.S.; Krueger, K.R.; Arnold, S.E.; Schneider, J.A.; Kelly, J.F.; Barnes, L.L.; Tang, Y.; Bennett, D.A. Loneliness and Risk of Alzheimer Disease. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2007, 64, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Windsor, T.D.; Gerstorf, D.; Pearson, E.; Ryan, L.H.; Anstey, K.J. Positive and negative social exchanges and cognitive aging in young-old adults: Differential associations across family, friend, and spouse domains. Psychol. Aging 2014, 29, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutet, I.; Milgram, N.W.; Freedman, M. Cognitive decline and human (Homo sapiens) aging: An investigation using a comparative neuropsychological approach. J. Comp. Psychol. 2007, 121, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK). Dementia: A NICE-SCIE Guideline on Supporting People with Dementia and Their Carers in Health and Social Care; British Psychological Society: Leicester, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sonderegger, A.; Schmutz, S.; Sauer, J. The influence of age in usability testing. Appl. Ergon. 2016, 52, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, N.; Hassanein, K.; Head, M. The impact of age on website usability. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 37, 270–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Rau, P.-L.P.; Salvendy, G. Use and Design of Handheld Computers for Older Adults: A Review and Appraisal. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2012, 28, 799–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilla, D.; Botella, C.; Miralles, I.; Bretón-lópez, J.; Dragomir-davis, A.; Zaragoza, I.; Garcia-palacios, A. Teaching digital literacy skills to the elderly using a social network with linear navigation: A case study in a rural area. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2018, 118, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, T. Usability for Older Web Users. Available online: https://www.webcredible.com/blog/usability-older-web-users/ (accessed on 25 March 2019).

- Hogan, M. Age Differences in Technophobia: An Irish Study. In Information Systems Development; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 117–130. [Google Scholar]

- Chua, S.L.; Chen, D.-T.; Wong, A.F.L. Computer anxiety and its correlates: A meta-analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 1999, 15, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chen, J. Overcoming technophobia in poorly-educated elderly—The HELPS-seniors service learning program. Int. J. Autom. Smart Technol. 2015, 5, 173–182. [Google Scholar]

- Friemel, T.N. The digital divide has grown old: Determinants of a digital divide among seniors. New Media Soc. 2016, 18, 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vroman, K.G.; Arthanat, S.; Lysack, C. “Who over 65 is online?” Older adults’ dispositions toward information communication technology. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 43, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wargnier, P.; Benveniste, S.; Jouvelot, P.; Rigaud, A.S. Usability assessment of interaction management support in LOUISE, an ECA-based user interface for elders with cognitive impairment. Technol. Disabil. 2018, 30, 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campoverde-Molina, M.; Lujan-Mora, S.; Garcia, L.V. Empirical Studies on Web Accessibility of Educational Websites: A Systematic Literature Review. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 91676–91700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission Web Accessibility | Shaping Europe’s Digital Future. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/web-accessibility (accessed on 7 July 2020).

- European Commission. Directive (EU) 2016/2102 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 October 2016 on the accessibility of the websites and mobile applications of public. Document 32016L2102 sector bodies. Off. J. Eur. Union. 2016, L327, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- W3C Web Accessibility Initiative WAI. Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) Overview. Available online: https://www.w3.org/WAI/standards-guidelines/wcag/ (accessed on 7 July 2020).

- W3C Web Accessibility Initiative WAI. Overview of “Web Accessibility for Older Users: A Literature Review”. Available online: https://www.w3.org/WAI/older-users/literature/ (accessed on 6 July 2020).

- W3C Web Accessibility Initiative WAI. Cognitive Accessibility at W3C | Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) | W3C. Available online: https://www.w3.org/WAI/cognitive/ (accessed on 6 July 2020).

- Castilla, D.; Garcia-Palacios, A.; Miralles, I.; Breton-Lopez, J.; Parra, E.; Rodriguez-Berges, S.; Botella, C. Effect of Web navigation style in elderly users. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 55, 909–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthanat, S. Promoting Information Communication Technology Adoption and Acceptance for Aging-in-Place: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2019. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31782347/ (accessed on 6 April 2020).

- Fernando, S.; Money, A.; Elliman, T.; Lines, L. Developing assistive web-base technologies for adults with age-related cognitive impairments. Transform. Gov. People Process Policy 2009, 3, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haesner, M.; Steinert, A.; O’Sullivan, J.L.; Steinhagen-Thiessen, E. Evaluating an accessible web interface for older adults—The impact of mild cognitive impairment (MCI). J. Assist. Technol. 2015, 9, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauriks, S.; Reinersmann, A.; Van der Roest, H.G.; Meiland, F.J.; Davies, R.J.; Moelaert, F.; Mulvenna, M.D.; Nugent, C.D.; Dröes, R.M. Review of ICT-based services for identified unmet needs in people with dementia. Ageing Res. Rev. 2007, 6, 223–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, G.R.; Owsley, C. Visual dysfunction, neurodegenerative diseases, and aging. Neurol. Clin. 2003, 21, 709–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, M.; Anderson, S.W.; Dawson, J.; Nawrot, M. Vision and cognition in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychologia 2000, 38, 1157–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, M.; Sparks, J.; McEvoy, S.; Viamonte, S.; Kellison, I.; Vecera, S.P. Change blindness, aging, and cognition. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2009, 31, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caird, J.K.; Edwards, C.J.; Creaser, J.I.; Horrey, W.J. Older Driver Failures of Attention at Intersections: Using Change Blindness Methods to Assess Turn Decision Accuracy. Hum. Factors J. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 2005, 47, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitenton, K. Change Blindness Causes People to Ignore What Designers Expect Them to See. Available online: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/change-blindness/ (accessed on 25 March 2019).

- García-Betances, R.I.; Cabrera-Umpiérrez, M.F.; Ottaviano, M.; Pastorino, M.; Arredondo, M.T. Parametric Cognitive Modeling of Information and Computer Technology Usage by People with Aging- and Disability-Derived Functional Impairments. Sensors 2016, 16, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras-Somoza, L.M.; Irazoki, E.; Castilla, D.; Cristina, B.; Toribio-guzmán, J.M.; Parra-Vidales, E.; Suso-Ribera, C.; Suárez-López, P.; Perea-Bartolomé, M.V.; Franco-Martín, M.Á. Study on the acceptability of an ICT platform for older adults with mild cognitive impairment. J. Med. Syst. 2020, 44, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. ehcoBUTLER. A Global Ecosystem for the Independent and Healty Living of Elder People with Mild Cognitive Impairments. | Projects | H2020 | CORDIS | Grant Agreement ID: 643566. 2018. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/rcn/194077/factsheet/en (accessed on 25 March 2019).

- Castilla, D.; Garcia-Palacios, A.; Bretón-López, J.; Miralles, I.; Baños, R.M.; Etchemendy, E.; Farfallini, L.; Botella, C. Process of design and usability evaluation of a telepsychology web and virtual reality system for the elderly: Butler. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2013, 71, 350–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J. Usability Engineering; Academic Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Dumas, J.S.; Redish, J. A Practical Guide to Usability Testing; Intellect Books: Exeter, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Mateos, R.; Franco, M.; Sanchez, M. Care for dementia in Spain: The need for a nationwide strategy. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2010, 25, 881–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Europe, A. Spain—National Dementia Strategies—Policy in Practice. Available online: https://www.alzheimer-europe.org/Policy-in-Practice2/National-Dementia-Strategies/Spain (accessed on 29 March 2019).

- Arriola, E.; Carnero, C.; Freire, A.; López-Mogil, R.; López-Trigo, J.A.; Manzano, S.; Olazarán, J. Deterioro Cognitivo Leve en el Adulto Mayor. Documento de Consenso; Sociedad Española de Geriatría y Gerontología, Ed.; Sociedad Española de Geriatría y Gerontología: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Botella, C.; Etchemendy, E.; Castilla, D.; Baños, R.M.; García-Palacios, A.; Quero, S.; Alcañiz, M.; Lozano, J.A. An e-health system for the elderly (Butler Project): A pilot study on acceptance and satisfaction. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2009, 12, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorish, C.D.; Maisiak, R. The face scale: A brief, nonverbal method for assessing patient mood. Arthritis Rheum. 1986, 29, 906–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, R.A.; Arruda, J.E.; Hooper, C.R.; Wolfner, G.D.; Morey, C.E. Visual analogue mood scales to measure internal mood state in neurologically impaired patients: Description and initial validity evidence. Aphasiology 1997, 11, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Dawes, P.; Leroi, I.; Gannon, B. Measurement tools of resource use and quality of life in clinical trials for dementia or cognitive impairment interventions: A systematically conducted narrative review. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2017, 33, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.; Staveland, L. Development of NASA-TLX (Task Load Index): Results of empirical and theoretical research. In Human Mental Workload; Hancock, P., Meshkati, N., Eds.; North Holland Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1988; pp. 139–183. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct. Available online: https://www.apa.org/ethics/code/ (accessed on 3 February 2020).

- National Institute on Aging. Making Your Web Site Senior Friendly: A Checklist. Available online: https://www.hsdl.org/?view&did=770661 (accessed on 14 June 2020).

- Christopher Mayer, C.; Morandell, M.; Gira, M.; Fagel, S. AAL Joint Programme Ambient Assisted Living User Interfaces AALuis i Project Identification Ambient Assisted Living User Interfaces; European Commission: Brusels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Freiherr, J.; Lundström, J.N.; Habel, U.; Reetz, K. Multisensory integration mechanisms during aging. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Hirtle, S.C. Spatial metaphors and disorientation in hypertext browsing. Behav. Inf. Technol. 1995, 14, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Techentin, C.; Voyer, D.; Voyer, S.D. Spatial Abilities and Aging: A Meta-Analysis. Exp. Aging Res. 2014, 40, 395–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, Y.; Bradley, M.D.; Hodgson, F.; Lloyd, A.D. Learning to use new technologies by older adults: Perceived difficulties, experimentation behaviour and usability. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 1715–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, P.; Mandler, G. Activation makes words more accessible, but not necessarily more retrievable. J. Verbal Learn. Verbal Behav. 1984, 23, 553–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandler, G. Recognizing: The judgment of previous occurrence. Psychol. Rev. 1980, 87, 252–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Task Performance | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fail | Success | |||

| User Felt | Very bad | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bad | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| Neutral | 1 | 4 | 5 | |

| Good | 0 | 15 | 15 | |

| Very good | 0 | 5 | 5 | |

| Total | 3 | 25 | 28 | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Castilla, D.; Suso-Ribera, C.; Zaragoza, I.; Garcia-Palacios, A.; Botella, C. Designing ICTs for Users with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Usability Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5153. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17145153

Castilla D, Suso-Ribera C, Zaragoza I, Garcia-Palacios A, Botella C. Designing ICTs for Users with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Usability Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(14):5153. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17145153

Chicago/Turabian StyleCastilla, Diana, Carlos Suso-Ribera, Irene Zaragoza, Azucena Garcia-Palacios, and Cristina Botella. 2020. "Designing ICTs for Users with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Usability Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 14: 5153. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17145153

APA StyleCastilla, D., Suso-Ribera, C., Zaragoza, I., Garcia-Palacios, A., & Botella, C. (2020). Designing ICTs for Users with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Usability Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(14), 5153. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17145153