Promoting a Safe Environment in Our Cities: Towards a Theoretical Model of “Moral Deficit” for Appropriate Psychopathic Therapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background of the Study

2.1. Theoretical Aspects: The Concept of Moral Deficit

SS ethics combined deontological, consequentialist and perfectionist approaches organized around moral concepts such as duty, the good and virtuousness while at the same time bereaving these concepts of their universal nature. … [T]his way of restricting the common good to one people legitimated every kind of violence, after all. By attributing value only to part of humanity, SS ethics pursued excessive egotism, thus at the same time showing a strong nihilistic component.

We had the moral right, we had the duty towards our people to kill this people which wanted to kill us. But we do not have the right to enrich ourselves with so much as a fur, with a watch, with a Mark or with a cigarette or anything else.

Heinrich Himmler is mostly seen as the all-powerful organizer who coordinated the police apparatus that reigned over occupied Europe and who personally supervised the concentration camp system. But Himmler was also a thinker or, at least, he perceived himself as such, and he was especially concerned with moral issues. … From a normative viewpoint any claim to philosophical validity for this type of approach may be called into question, for the nihilism and denial of otherness were paramount in the instrumentalization of humans that led to genocide.

- Universalising the intentions of moral actions to others.

- Consistently applying universalisations based on principles for all persons.

2.2. Theoretical Aspects: The Concept of Psychopathy

a constellation of psychological symptoms that typically emerges early in childhood and affects all aspects of a sufferer’s life including relationships with family, friends, work, and school. The symptoms of psychopathy include shallow affect, lack of empathy, guilt and remorse, irresponsibility, and impulsivity.

Psychopathy is astonishingly common as mental disorders go. It is twice as common as schizophrenia, anorexia, bipolar disorder, and paranoia, and roughly as common as bulimia, panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, and narcissism.

2.3. Practical Aspects: Recidivism Among Psychopaths

3. Methodology

Observation is always selective. It needs a chosen object, a definite task, an interest, a point of view, a problem. And its description presupposes a descriptive language, with property words; it presupposes similarity and classification, which in their turn presuppose interests, points of view, and problems.

While research traditions generate quite varied research products—ranging from formal models and causal inferences to historical narratives and ethnographies—we follow Andrew Abbott [31] in viewing all of these as offering causal stories based on particular “explanatory programs”.

the investigation of differently formulated analytic problems within contending research traditions frequently offer relevant insights for the purposes of solving substantive problems. The challenge is to compare and selectively integrate these insights so that they can be more practically useful in relation to substantive problems. Given their expanded scope, the kinds of problems addressed by eclectic scholars are more likely to have concrete implications for the messy substantive problems facing policymakers and ordinary social and political actors. (emphasis added)

The directed approach does present challenges to the naturalistic paradigm. Using theory has some inherent limitations in that researchers approach the data with an informed but, nonetheless, strong bias. Hence, researchers might be more likely to find evidence that is supportive rather than non- supportive of a theory.

4. Results: Eclectic Psychiatric Reports, Historical Narrative and Rehabilitation Research

4.1. Eclectic Secondary Data: Violent Terrorists with Psychopathic Tendencies

On 22 July 2011, at 3:35 p.m., Anders Behring Breivik set off a car bomb in front of the office of Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg and other government buildings in Oslo. The explosion killed eight and wounded over 200 people. Less than two hours later, at a summer camp on the island of Utøya run by the Workers’ Youth League, the youth division of the ruling Norwegian Labor Party, Breivik, wearing a homemade police uniform, opened fire, killing 69 and wounding 110, mostly teenagers.

The year 2015 saw an upsurge in terrorist attacks on Western countries that were reportedly inspired by Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS). A number of less serious incidents have also occurred including the stabbing of three passengers on the London Underground rail network on 5 December.

4.2. Psychopathic Therapy and Rehabilitation

Law and psychiatry, even at the zenith of their rehabilitative optimism, both viewed psychopaths as a kind of exception that proved the rehabilitative rule. Psychopaths composed that small but embarrassing cohort whose very resistance to all manner of treatment seemed to be its defining characteristic.

Traditional treatments within the criminal justice system are relatively ineffective for psychopathic offenders. One possible explanation is that these treatments do not address the unique patterns of dysfunctions present in psychopathic individuals. Findings that the two factors are associated with distinctive cognitive-affective functions, from our studies and others, strongly suggest that developing evidence-based treatments depends upon targeting the unique factor-specific deficits. Directly translating the current results into clinical practice would suggest that individuals with higher scores on Factor 1 will not be able to utilize aversive learning to shape behaviour, and so alternative strategies are required.

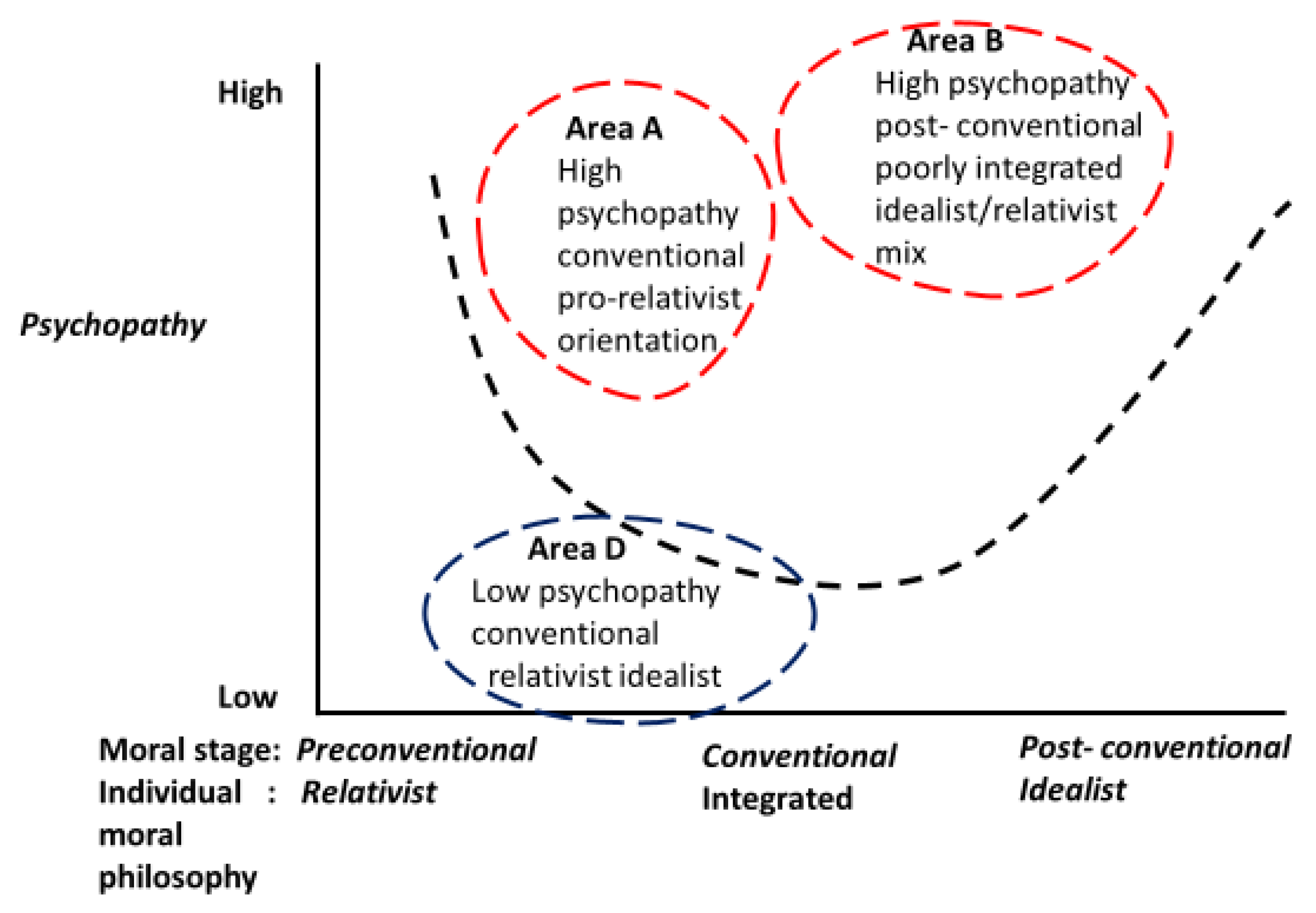

5. The Development of an Exploratory Model of Specific Violent Psychopathic-Type Individuals with Low Effective Therapy and High Recidivism Propensities

- Post-conventional levels of moral development [9].

- High levels of measured psychopathy and violent criminal behaviour.

- Poor prospects of rehabilitation through extant therapeutic practices.

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Forsyth, D.R. A taxonomy of ethical ideologies. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, D.R. Individual differences in information integration during moral judgment. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 49, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, D.R. Judging the morality of business practices: The influence of personal moral philosophies. J. Bus. Ethic. 1992, 11, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, D.R. Values, conceptions of science, and the social psychological study of morality. In The Role of. Values in Psychology and Human Development; Kurtines, W.M., Azmitia, M., Gewirtz, J.L., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Schlenker, B.R.; Forsyth, D.R. On the ethics of psychological research. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1977, 13, 369–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialas, W.; Fritze, L. Nazi Ideology and Ethics; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wachsmann, N. KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps; Little Brown: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mineau, A. Himmler’s ethics of duty: A moral approach to the Holocaust and to Germany’s impending defeat. Euro. Leg. 2007, 12, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanford, J.T.; Kohlberg, L. The Philosophy of Moral Development. J. Sci. Study Relig. 1982, 21, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B.; Brown, J.A.; Buchholtz, A.K. Business & Society: Ethics, Sustainability, and Stakeholder Management; Engage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Barger, R.N. Philosophical Belief Systems. Retrieved 9 September 2009. Available online: http://www.nd.edu/~rbarger/philblfs.html (accessed on 23 October 2018).

- Glenn, A.L.; Iyer, R.; Graham, J.; Koleva, S.; Haidt, J. Are all types of morality compromised in psychopathy? J. Pers. Disord. 2009, 23, 384–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, J. The amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex in morality and psychopathy. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2007, 11, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, R. A cognitive developmental approach to morality: Investigating the psychopath. Cognition 1995, 57, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deigh, J. Empathy and universability. Ethics 1995, 105, 743–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiehl, K.A.; Hoffman, M.B. The criminal psychopath: History, neuroscience, treatment, and economics. Jurimetrics 2011, 51, 355–397. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Forsyth, D.R. Making Moral Judgements: Psychological Perspectives on Morality, Ethics and Decision-Making; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Levenson, M.R.; Kiehl, K.A.; Fitzpatrick, C.M. Assessing psychopathic attributes in a noninstitutionalized population. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 68, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, R.J.R. Neurobiological basis of psychopathy. Br. J. Psychiatry 2003, 182, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raine, A.; Buchsbaum, M.; Lacasse, L. Brain abnormalities in murderers indicated by positron emission tomography. Boil. Psychiatry 1997, 42, 495–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hare, R.D.; Clark, D.; Grann, M.; Thornton, D. Psychopathy and the predictive validity of the PCL-R: An international perspective. Behav. Sci. Law 2000, 18, 623–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hare, R.D.; Neumann, C.S. The PCL-R assessment of psychopathy: Development, structural properties, and new directions. In Handbook of Psychopathy; Patrick, C., Ed.; The Guildford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hare, R.D. The Psychopathy Checklist-Revised; Multi-Health Systems: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Silver, E.; Mulvey, E.P.; Monahan, J. Assessing violence risk among discharged psychiatric patients: Toward an ecological approach. Law Hum. Behav. 1999, 23, 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boslaugh, S. Secondary Data Sources for Public Health; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Vartanian, Y.P. Secondary Data Analysis; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Popper, K.R. Objective Knowledge: An. Evolutionary Approach; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, M.; Barbera, J.R. Dictionary of Cultural and Critical Theory, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Popper, K.R. Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge; Routledge Classics: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sil, R.; Katzenstein, P.J. Analytic eclecticism in the study of world politics: Reconfiguring problems and mechanisms across research traditions. Perspect. Politi. 2010, 8, 411–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbot, A. Methods of Discovery: Heuristics for the Social Sciences; W.W. Norton: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to content analysis. Qual. Health. Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuurman, B. Research on Terrorism, 2007–2016: A Review of Data, Methods, and Authorship. Terror. Political Violence 2018, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollenberg, D. The new knighthood: Terrorism and the medieval. Postmedieval 2014, 5, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Melle, I. The Breivik case and what psychiatrists can learn from it. World Psychiatry 2013, 12, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browne, A. I Feel no Sympathy for You: Killer Tells van Gogh Family. The Times. 13 July 2005. Available online: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/ (accessed on 14 April 2020).

- Nesser, P.; Stenersen, A.; Oftedal, E. Jihadi terrorism in Europe: The IS-effect. Perspect. Terror. 2016, 10, 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, S. Allies under attack: The terrorist threat to Europe. In Program. on Extremism; George Washington University: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. Available online: https://docs.house.gov/meetings (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- Bartholomew, R.E. The Paris terror attacks, mental health and the spectre of fear. J. R. Soc. Med. 2016, 109, 4–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grierson, J. Islamic Extremists Remains Dominant UK Terror Threat, Say Experts. The Guardian. December 2019. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2019/dec/ (accessed on 10 April 2020).

- Duncan, P.; Stubley, P. London Bridge Attack: First Victim Named as Pressure Mounts on Johnson for Investigation into Release of Convict Taught by Anjem Choudary. The Guardian. December 2019. Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/crime/london-bridge-attack (accessed on 10 April 2020).

- Kozhuharova, P.; Dickson, H.; Tully, J.; Blackwood, N. Impaired processing of threat in psychopathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of factorial data in male offender populations. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0224455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baskin-Sommers, A.R.; Curtin, J.J.; Newman, J.P. Altering the cognitive-affective dysfunctions of psychopathic and externalizing offender subtypes with cognitive remediation. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 3, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, M.F.; Van Rybroek, G.J. Efficacy of a decompression treatment model in the clinical management of violent juvenile offenders. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2001, 45, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, M.; McCormick, D.J.; Umstead, D.; Van Rybroek, G.J. Evidence of treatment progress and therapeutic outcomes among adolescents with psychopathic features. Crim. Justice Behav. 2007, 34, 573–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cima, M.; Tonnaer, F.; Hauser, M.D. Psychopaths know right from wrong but don’t care. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2010, 5, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, B.L.; Lune, H. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kipping, M.; Wadhwani, R.D.; Bucheli, M. Analysing and Interpreting Historical Sources: A Basic Methodology. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301093205_Analyzing_and_Interpreting_Historical_Sources_A_Basic_Methodology (accessed on 21 June 2020).

- Stinchcombe, A.L. The Logic of Social Research; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Coldwell, D.; Coldwell, S. Promoting a Safe Environment in Our Cities: Towards a Theoretical Model of “Moral Deficit” for Appropriate Psychopathic Therapy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4968. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17144968

Coldwell D, Coldwell S. Promoting a Safe Environment in Our Cities: Towards a Theoretical Model of “Moral Deficit” for Appropriate Psychopathic Therapy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(14):4968. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17144968

Chicago/Turabian StyleColdwell, David, and Sarah Coldwell. 2020. "Promoting a Safe Environment in Our Cities: Towards a Theoretical Model of “Moral Deficit” for Appropriate Psychopathic Therapy" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 14: 4968. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17144968

APA StyleColdwell, D., & Coldwell, S. (2020). Promoting a Safe Environment in Our Cities: Towards a Theoretical Model of “Moral Deficit” for Appropriate Psychopathic Therapy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(14), 4968. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17144968