Improving Mental Health Help-Seeking Behaviours for Male Students: A Framework for Developing a Complex Intervention

Abstract

1. Introduction

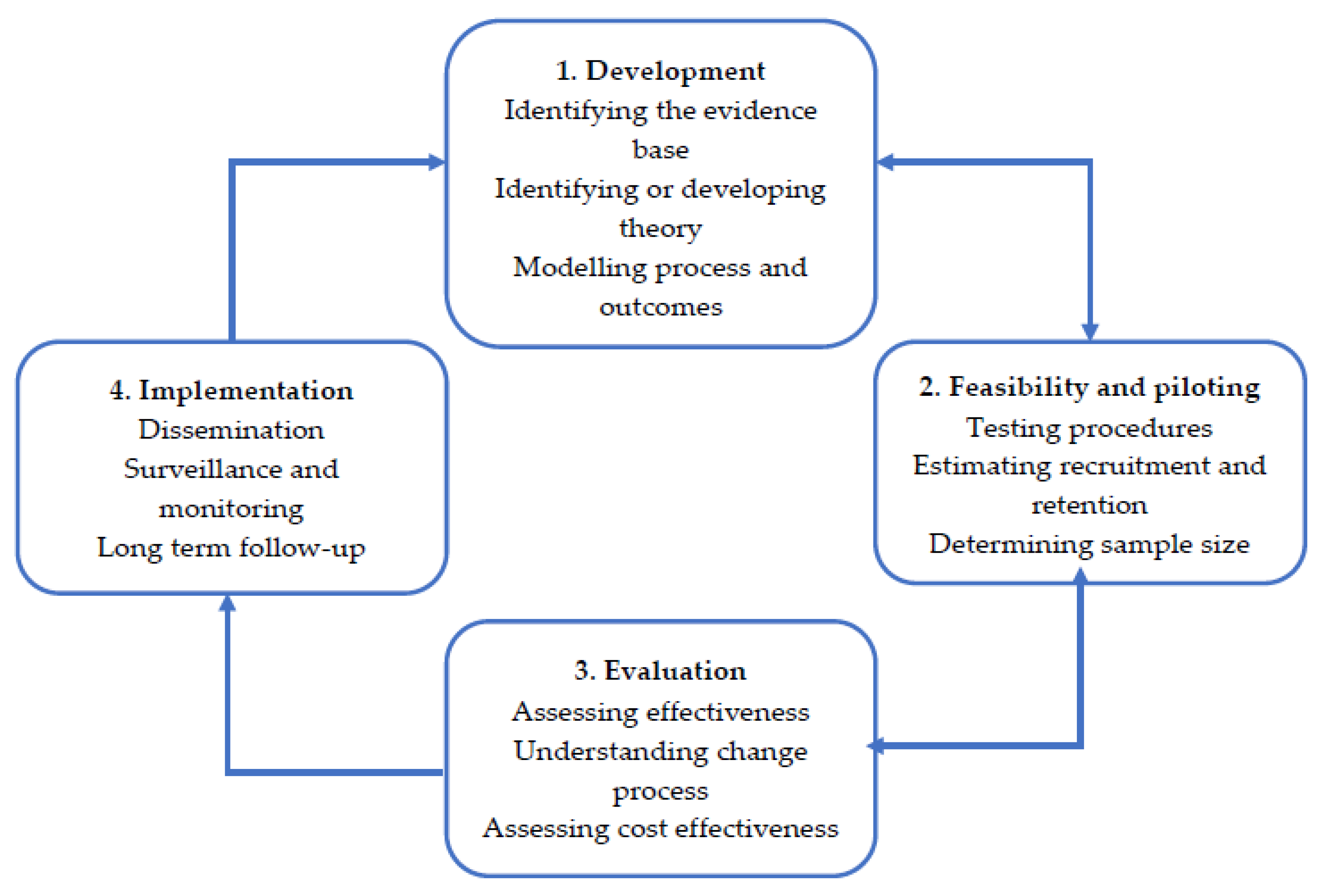

2. Medical Research Council (MRC) Framework

2.1. MRC Development: Identifying the Evidence Base.

Identifying Evaluation Methods

2.2. MRC Development: Identifying or Developing Theory

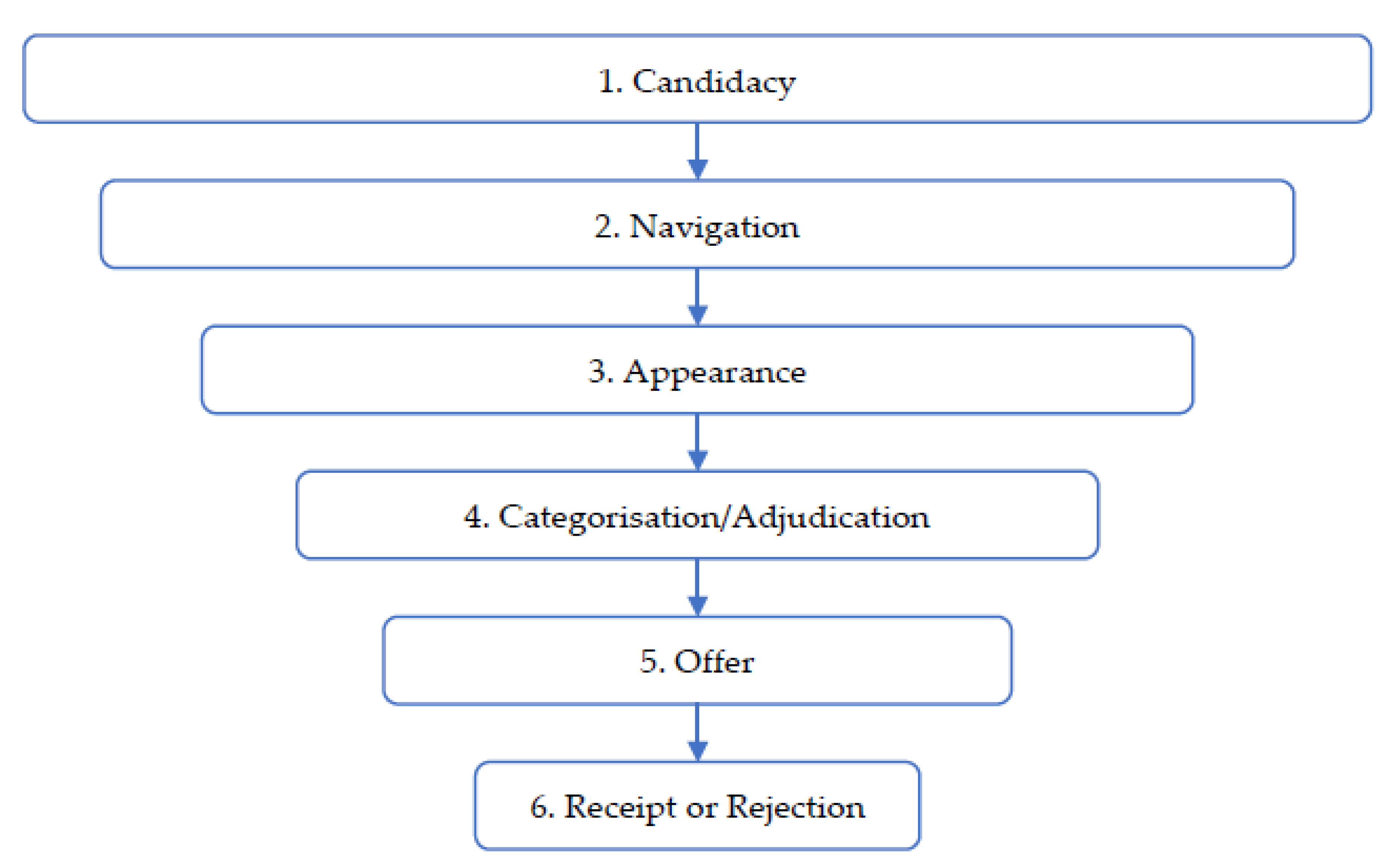

2.2.1. Access to Care Model

Candidacy

Appearance

Categorisation/Adjudication and Offer

Receipt or Rejection

2.2.2. Other Considerations

2.3. MRC Development: Modelling Process and Outcomes

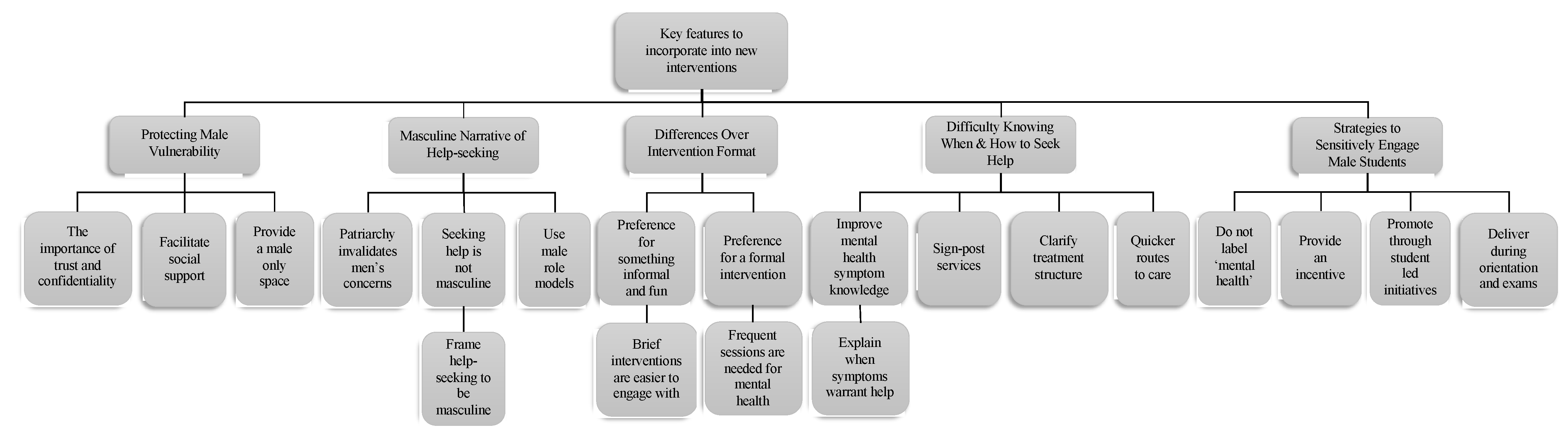

2.3.1. Modelling Process and Outcomes: Focus Groups

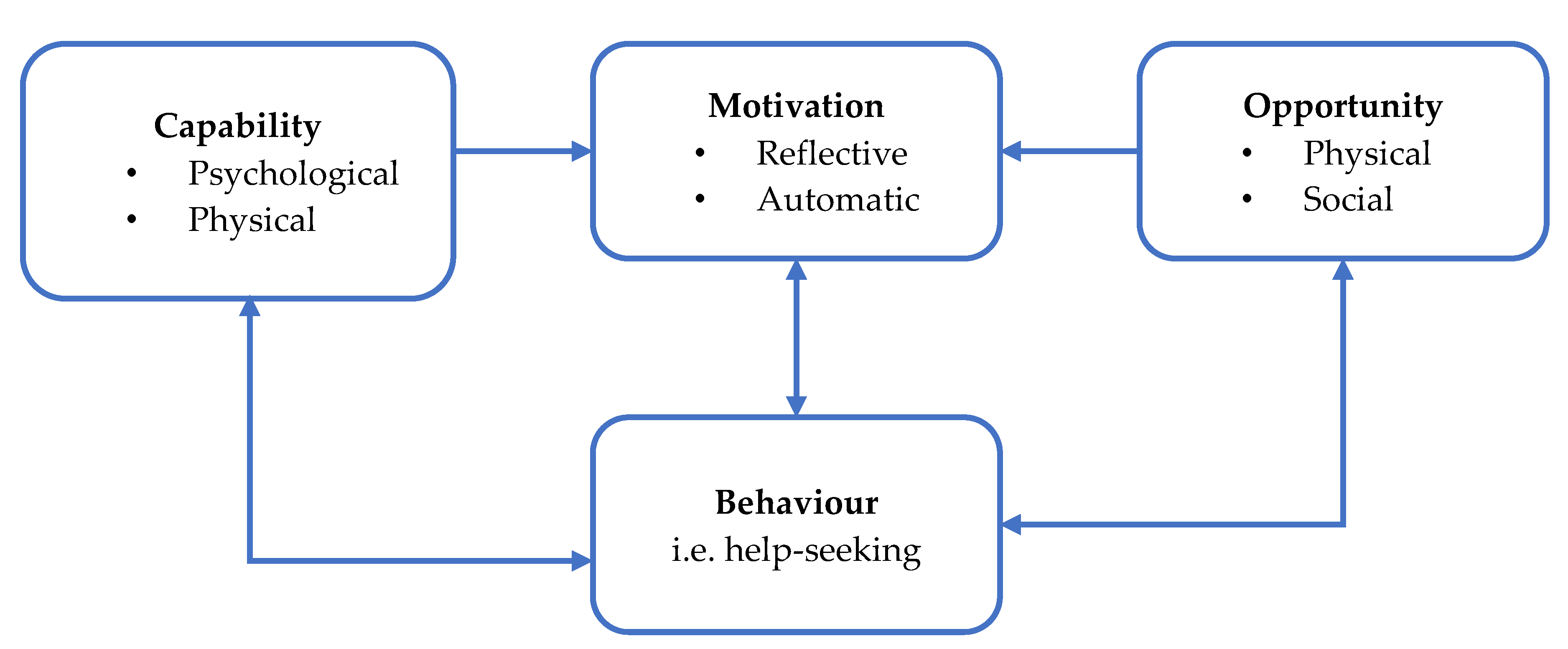

2.3.2. Modelling Process and Outcomes: The COM-B Model of Behaviour

3. MRC Feasibility and Piloting

4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Item | Description | Manuscript |

| 1. Report the context for which the intervention was developed. | Understanding the context in which an intervention was developed informs readers about the suitability and transferability of the intervention to the context in which they are considering evaluating, adapting or using the intervention. | “It is essential for the intervention development process to be reported as this can enhance our theoretical and practical understanding about developing mental health interventions for male students [25]”. In response to this, the current paper seeks to develop the first framework for developing and designing mental health interventions for male students that is grounded in evidence-based practice. |

| 2. Report the purpose of the intervention development process. | Clearly describing the purpose of the intervention specifies what it sets out to achieve. The purpose may be informed by research priorities, for example those identified in systematic reviews, evidence gaps set out in practice guidance, such as the NICE, or specific prioritisation exercises. | “The MRC framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions will be used with the Behaviour Change Wheel to develop a framework for new interventions that address help-seeking in male students. It is anticipated that this framework will create a starting point for future interventions which can be refined as the current evidence base is enriched. Furthermore, specific detail in accordance to the Guidance for Reporting Intervention Development Studies in Health Research (GUIDED) checklist has been included (Appendix A) to further enrich the quality of evidence that is reported within the current paper [25].” |

| 3. Report the target population for the intervention development process. | The target population is the population that will potentially benefit from the intervention–this may include patients, clinicians and/or members of the public. If the target population is clearly described, then readers will be able to understand the relevance of the intervention to their own research or practice. Health inequalities, gender and ethnicity are features of the target population that may be relevant to the intervention development process. | “In response to this, the current paper seeks to develop the first framework for developing and designing mental health interventions for male students that is grounded in evidence-based practice.” |

| 4. Report how any published intervention development approach contributed to the development process. | Many formal intervention development approaches exist and are used to guide the intervention development process. Where a formal intervention development approach is used, it is helpful to describe the process that was follows, including any deviations. | “This paper will discuss the development of an intervention using a published approach grounded in theory and evidence base by combining published research evidence and existing theories [27]. The MRC framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions will be used with the Behaviour Change Wheel to develop a framework for new interventions that address help-seeking in male students.” |

| 5. Report how evidence from different sources informed the intervention development process. | Intervention development is often based on published evidence and/or primary data that have been collected to inform the intervention development process. It is useful to describe and reference all forms of evidence and data that have informed the development of the intervention because evidence bases can change rapidly, and to explain the manner in which the evidence and/or data were used. | “This paper will discuss the development of an intervention using a published approach grounded in theory and evidence base by combining published research evidence and existing theories [27].”This paper also incorporates published systematic reviews and qualitative findings from focus groups into the development of the intervention throughout the paper. |

| 6. Report how/if existing published theory informed the intervention development process. | Reporting whether and how theory informed the development process aids the reader’s understanding of the theoretical rationale that underpins the intervention. This can relate to either existing published theory or programme theory. | This is utilised throughout the paper. The paper draws upon published evidence from systematic reviews, qualitative findings from focus groups and theory informed research structured within the ‘access to care model’. |

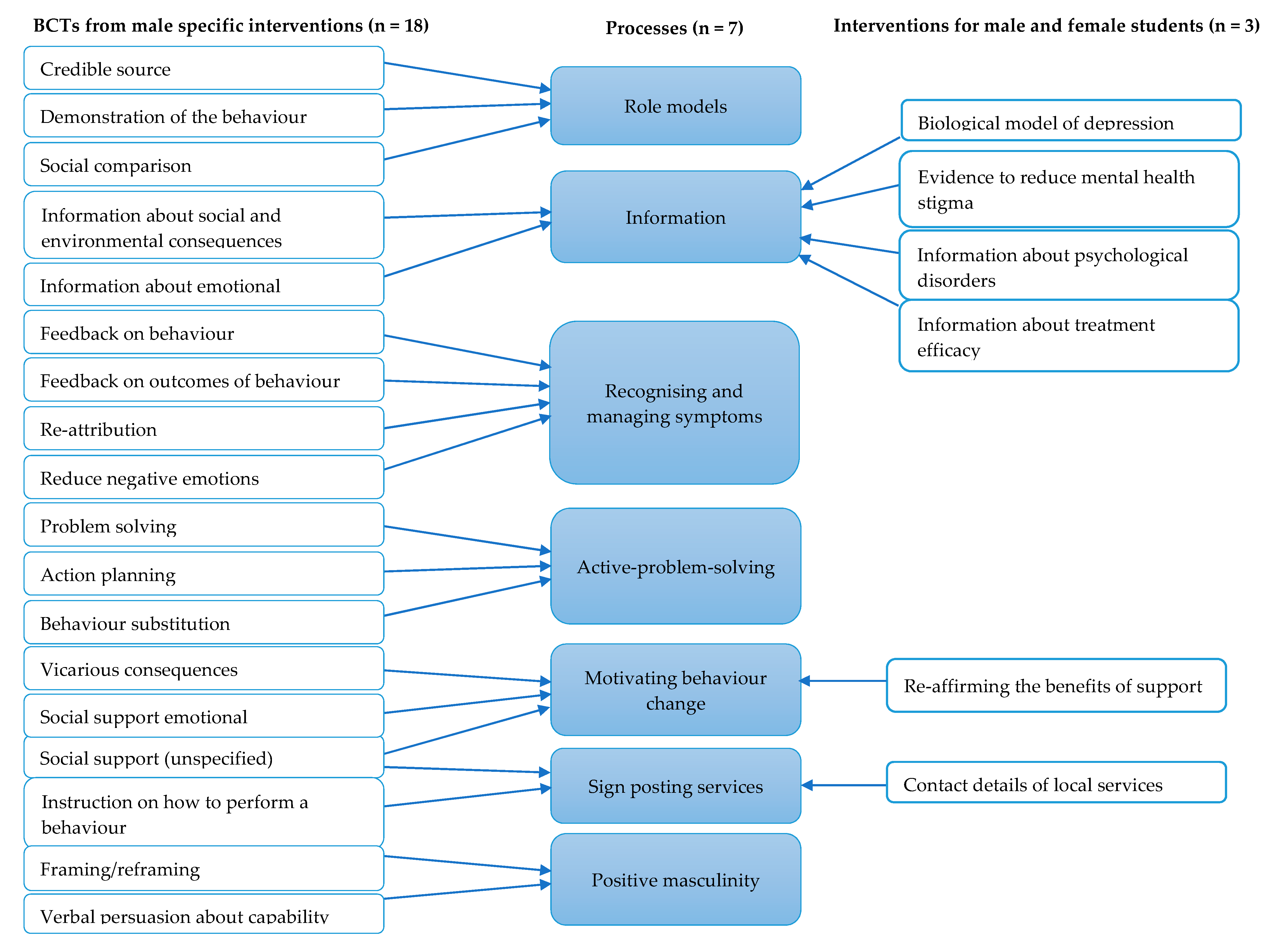

| 7. Report any use of components from an existing intervention in the current intervention development process. | Some interventions are developed with components that have been adopted from existing interventions. Clearly identifying components that have been adopted or adapted and acknowledging their original source helps the reader to understand and distinguish between the novel and adopted components of the new intervention. | “Sagar-Ouriaghli and colleagues [22] identified 18 BCTs (e.g., credible source, feedback on behaviour and problem solving), which were in turn synthesised into broader, more clinically relevant, psychological processes that are likely to contribute to changes in help-seeking for men of different age groups (Appendix B). These seven key processes include: the use of role models (e.g., celebrities and other men) to convey information, psycho-educational materials to improve mental health knowledge, assisting men to recognise and manage their symptoms, adopting active problem solving and/or solution focused tasks, motivating behaviour change, sign-posting mental health services and finally, including content to build on positive masculine traits (e.g., responsibility and strength).” |

| 8. Report any guiding principles, people or factors that were priorities when making decisions during the intervention development process. | Reporting any guiding principles that governed the development of the intervention will help the reader to understand the authors’ reasoning behind the decisions that were made. Guiding principles specify the core objectives and features of the desired intervention. | “Lastly, not all intervention functions should be implemented, and should be chosen based on their affordability, practicability, effectiveness/cost-effectiveness, acceptability, side-effects/safety and equity–otherwise known as the APEASE criteria [103]. … Once all potential BCT’s have been identified, the APEASE criteria is used once more to determine which specific techniques or tools are most appropriate. Additionally, BCT’s that have been frequently used before in similar interventions may also aid in this decision [22,103].” |

| 9. Report how stakeholders contributed to the intervention development process. | Potential stakeholders can include patient and community representatives, local and national policy makers, healthcare providers, and those paying for or commissioning healthcare. Each of these groups may influence the intervention development process in different ways. | The intervention development outlines how the theory informed components are also based on focus group findings from the potential service users of a male-student intervention for mental health help-seeking. |

| 10. Report how the intervention changed in content and format from the start of the intervention development process. | Due to the iterative nature of intervention development, the intervention that is defined in the end of the development process can often be quite different from the one that was initially planned. Describing these changes and their rationale enhances understanding and enables understanding other intervention developers to learn from this experience. | This is not applicable to the current paper. Here, the current paper outlines key factors that are likely to be important that can be used as a template/framework for future interventions. In the instance that interventions are developed following this framework, any changes to the intervention/deviation from the proposed framework should be reported here. |

| 11. Report any changes to interventions required or likely to be required for subgroups. | Specifying any changes that the intervention development team perceive are required for the intervention to be delivered or tailored to specific subgroups enables readers to understand the applicability of the intervention to their target population or context. | This is not applicable to the current paper. Here, the current paper seeks to provide a broad overview of the factors which are likely to be effective when designing mental health interventions for male students. Therefore, broad intervention strategies are outlined. If a more specific sub-group of male students is the focus of a newly proposed intervention this should be stated in future work. |

| 12. Report important uncertainties at the end of the intervention development process. | Intervention development is frequently an iterative process. The conclusion of the initial phase of intervention development does not necessarily mean that all uncertainties have been addressed. It is helpful to list remaining uncertainties, such as the intervention intensity, mode of delivery, materials, procedures or type of location that the intervention is most suitable for. This can guide other researchers to potential future areas of research and practitioners about uncertainties relevant to their healthcare context. | “Subsequently, the recommendations may not directly transfer to male-students. Indeed, younger adults are significantly less likely to seek help and hold more negative help-seeking attitudes [107,108], whilst students are also faced with barriers which may differ from non-students and older adult males. In an attempt to provide a comprehensive overview, the current paper is unable to provide more specific recommendations for sub-groups of male students. For instance, sexual minority male students or male students from ethnic minority backgrounds face different barriers and it is likely that they will need more tailored interventions to accommodate their needs and encourage help-seeking [109,110,111,112]. Lastly, this framework is yet to be implemented when designing future male-student help-seeking interventions. Although this paper synthesises evidence-based work specifically for men and male students, it is unclear as to how transferable and applicable this will be to real world scenarios. Indeed, it would be valuable to see how effective/ineffective this framework is for others developing mental health interventions for male students.” |

| 13. Follow TIDieR guidance when describing the developed intervention. | Interventions have been poorly reported for a number of years. In response to this, internationally recognised guidance has been published to support the high-quality reporting of healthcare interventions and public health interventions. This guidance should therefore be followed when describing a developed intervention. | This is not applicable to the current paper as it does not report a specific intervention, nor does it pilot the described intervention. However, the current paper recommends the use of TIDieR when interventions are designed in accordance to this framework. Furthermore, newly developed interventions should be reported in accordance to the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist to aid with replication and clarity of the final intervention [22,33].” |

| 14. Report the intervention development process in an open access format. | Unless reports of intervention development are available, people considering using an intervention cannot understand the process that undertaken and make a judgement about its appropriateness to their context. It also limits cumulative learning about intervention development mythology and observed consequences at later evaluation, translation and implementation stages. Reporting intervention development in an open access publishing format increases the accessibility and visibility of intervention development research and makes it more likely to be read and used. | The current paper was submitted and published in open access format in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health (IJERPH). |

Appendix B

Appendix C

| No. | Item | ||||

| 1. | How acceptable was the workshop? | ||||

| Completely Unacceptable | Unacceptable | No Opinion | Acceptable | Completely Acceptable | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 2. | Did you like or dislike the workshop? | ||||

| Strongly Dislike | Dislike | No Opinion | Like | Strongly Like | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 3. | How much effort did it take you to engage with the workshop? | ||||

| No effort at all | A little effort | No Opinion | A lot of effort | Huge effort | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 4. | The workshop fits with my beliefs about mental health and seeking mental health support | ||||

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | No Opinion | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 5. | It is clear to me how engaging in this workshop would help me manage my mental health | ||||

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | No Opinion | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Please tell us more about your views | |||||

| 6. | This workshop interfered with my other priorities | ||||

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | No Opinion | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 7a. | The workshop has improved my attitudes towards seeking professional help for my mental health | ||||

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | No Opinion | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 7b. | The workshop has improved my overall mental health/well-being | ||||

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | No Opinion | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 8. | How confident would you feel about engaging with this workshop again? | ||||

| Very Unconfident | Unconfident | No Opinion | Confident | Very Confident | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

References

- UCAS. UCAS Impact Report 2018. Available online: https://www.ucas.com/corporate/data-and-analysis/ucas-undergraduate-releases/ucas-undergraduate-analysis-reports/ucas-undergraduate-end-cycle-reports (accessed on 5 June 2020).

- Kessler, R.C.; Angermeyer, M.; Anthony, J.C.; De Graff, R.; Demyttenaere, K.; Gasquet, I.; De Girolamo, G.; Gluzman, S.; Gureje, O.; Haro, J.M.; et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry 2007, 6, 168–176. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2174588/ (accessed on 24 June 2020).

- Jones, P.B. Adult mental health disorders and their age of onset. Br. J. Psychiatry 2013, 202, s5–s10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiter, R.; Nash, R.; McCrady, M.; Rhoades, D.; Linscomb, M.; Clarahan, M.; Sammut, S. The prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety and stress in a sample of college students. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 173, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortier, P.; Cuijpers, P.; Kiekens, G.; Auerbach, R.P.; Demyttenaere, K.; Green, J.G.; Kessler, R.C.; Nock, M.K.; Bruffaerts, R. The prevelance of suicidal thoughts and behaviours among college students: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 2018, 48, 554–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macaskill, A. The mental health of university students in the United Kingdom. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2013, 41, 426–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, T.M.; Bira, L.; Gastelum, J.B.; Weiss, L.T.; Vanderford, N.L. Evidence for a mental health crisis in graduate education. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 282–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorley, C. Not by Degrees: Improving Student Mental Health in the UK’s Universities. Available online: https://www.ippr.org/research/publications/not-by-degrees (accessed on 5 June 2020).

- Chang, Q.; Yip, P.S.; Chen, Y. Gender inequality and suicide gender rations in the world. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 243, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Health Organization Suicide Fact Sheet. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide (accessed on 5 June 2020).

- Mental Health Foundation. Fundamental Facts About Mental Health 2016; Mental Health Foundation: London, UK, 2016; Available online: https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/publications/fundamental-facts-about-mental-health-2016 (accessed on 24 June 2020).

- Sheu, H.-B.; Sedkacek, W.H. An exploratory study of help-seeking attitudes and coping strategies among college students by race and gender. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 2004, 37, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, D.; Golberstein, E.; Gollust, S.E. Help-Seeking and Access to Mental Health Care in a University Student Population. Med. Care 2007, 594–601. Available online: www.jstor.org/stable/40221479 (accessed on 24 June 2020). [CrossRef]

- McManus, S.; Bebbington, P.; Jenkins, R.; Brugha, T. Mental Health and Wellbeing in England: Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2014; NHS Digital: Leeds, UK, 2016; Available online: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/adult-psychiatric-morbidity-survey/adult-psychiatric-morbidity-survey-survey-of-mental-health-and-wellbeing-england-2014 (accessed on 24 June 2020).

- Gulliver, A.; Griffiths, K.M.; Christensen, H. Percieved barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2010, 10, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, K.S.; Choi, S.I.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, A.R.; Lee, S.M. Psychological factors in college student’ attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help: A meta-analysis. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2013, 44, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addis, M.E.; Mahalik, J.R. Men, Masculinity and the Contexts of Help Seeking. Am. Psychol. 2003, 58, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.; McCrae, B.P.; Frank, J.; Dochnahl, A.; Pickering, T.; Harrison, B.; Zakrzewski, M.; Wilson, K. Identifying Male College Students’ Perceived Health Needs, Barriers to Seeking Help, and Recommendations to Help Men Adopt Healthier Lifestyles. J. Am. Coll. Health 2000, 48, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seamark, D.; Gabriel, L. Barriers to support: A qualitative exploration into the help-seeking and avoidance factors of young adults. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2018, 46, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.O.; Oliffe, J.L.; Galdas, P.M.; Phinney, A.; Han, C.S. College men’s depression-related help-seeking: A gender analysis. J. Ment. Health 2014, 23, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barkham, M.; Broglia, E.; Dufour, G.; Fudge, M.; Knowles, L.; Percy, A.; Turner, A.; Williams, C.; SCORE Consortium. Towards an evidence-base for student wellbeing and mental health: Definitions, developmental transitions and data sets. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2019, 19, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagar-Ouriaghli, I.; Godfrey, E.; Bridge, L.; Meade, L.; Brown, J.S. Improving Mental Health Service Utilization Among Men: A Systematic Review and Sythesis of Behavior Change Techniques Within Interventions Targeting Help-Seeking. Am. J. Mens. Health 2019, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochlen, A.B.; McKelley, R.A.; Pituch, K.A. A preliminary examination of the “Real Men. Real Depression” campaign. Psychol. Men Masc. 2006, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syzdek, M.R.; Green, J.D.; Lindgren, B.R.; Addis, M.E. Pilot trial of gender-based motivational interviewing for increasing mental health service use in college men. Psychotherapy 2016, 53, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, E.; O’Cathain, A.; Rousseau, N.; Croot, L.; Sworn, K.; Turner, K.M.; Yardley, L.; Hoddinott, P. Guidance for reporting intervention development studies in health research (GUIDED): An evidence-based consensus study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e033516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, P.; Dieppe, P.; Macintyre, S.; Michie, S.; Nazareth, I.; Petticrew, M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008, 337, a1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Cathain, A.; Croot, L.; Duncan, E.; Rousseau, N.; Sworn, K.; Turner, K.M.; Yardley, L.; Hoddinott, P. Guidance on how to develop complex interventions to improve health and healthcare. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e029954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulliver, A.; Griffiths, K.M.; Christensen, H.; Brewer, J.L. A systematic review of help-seeking interventions for depression, anxiety and general psychological distress. BMC Psychiatry 2012, 12, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.-Y.; Chen, S.-H.; Hwang, K.-K.; Wei, H.-L. Effects of psychoeducation for depression on help-seeking willingness: Biological attribution versus destigmatization. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2006, 60, 662–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharp, W.; Hargrove, D.S.; Johnson, L.; Deal, W.P. Mental health education: An evaluation of a classroom based strategy to modify help seeking for mental health problems. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2006, 47, 419–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohue, B.; Dickens, Y.; Lancer, K.; Covassin, T.; Hash, A.; Miller, A.; Genet, J. Improving athletes’ perspectives of sport psychology consultation: A controlled evaluation of two intervention methods. Behav. Modif. 2004, 28, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.K.; Chu, H.J.; Lee, M.K.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, N.; Lee, S.M. A meta-analysis of gender differences in attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help. J. Am. Coll. Health 2010, 59, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, T.C.; Glasziou, P.P.; Boutron, I.; Milne, R.; Perera, R.; Moher, D.; Altman, D.G.; Barbour, V.; Macdonald, H.; Johnston, M.; et al. Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014, 348, g1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Green, S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Michie, S.; Richardson, M.; Johnston, M.; Abraham, C.; Francis, J.; Hardeman, W.; Eccles, M.P.; Cane, J.; Wood, C.E. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: Building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann. Behav. Med. 2013, 46, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, E.H.; Farina, A. Attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help: A shortened form and considerations for research. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 1995, 36, 368–373. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1996-10056-001 (accessed on 24 June 2020).

- Rochlen, A.B.; Blazina, C.; Raghunathan, R. Gender Role Conflict, Attitudes Toward Career Counseling, Career Decision-Making, and Perceptions of Career Counseling Advertising Brochures. Psychol. Men Masc. 2002, 3, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, J.; Vogel, D. Men’s Help seeking for depression: The efficacy of a male-sensitive brochure about counselling. Couns. Psychol. 2010, 38, 296–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syzdek, M.R.; Addis, M.E.; Green, J.D.; Whorley, M.R.; Berger, J.L. A pilot trial of gender-based motivational interviewing for help-seeking and internalizing symptoms in men. Psychol. Men Masc. 2014, 15, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, E.H.; Turner, J.L. Orientations to seeking professional help: Development and research utility of an attitude scale. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1970, 35, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elahi, J.D.; Schweinle, W.; Anderson, S.M. Reliability and validity of the Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale-Short Form. Psychiatry Res. 2008, 159, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, C.J.; Deane, F.P.; Ciarrochi, J.V.; Rickwood, D. Measuring help seeking intentions: Properties of the general help seeking questionnaire. Can. J. Couns. 2005, 39, 15–28. Available online: https://ro.uow.edu.au/hbspapers/1527/ (accessed on 24 June 2020).

- Rickwood, D.; Deane, F.P.; Wilson, C.J.; Ciarrochi, J.V. Young people’s help-seeking for mental health problems. Aust. e-J. Adv. Ment. Health 2005, 4, 218–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickwood, D.; Thomas, K. Conceptual measurement framework for help-seeking for mental health problems. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2012, 5, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickwood, D.J.; Braithwaite, V.A. Social-psychological factors affecting help-seeking for emotional problems. Soc. Sci. Med. 1994, 39, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gask, L.; Bower, P.; Lamb, J.; Burroughs, H.; Chew-Graham, C.; Edwards, S.; Hibbert, D.; Kovandzic, M.; Lovell, K.; Rogers, A.; et al. AMP Research Group. Improving access to psychosocial interventions for common mental health problems in the United Kingdom: Narrative review and development of a conceptual model for complex interventions. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon-Woods, M.; Cavers, D.; Agarwal, S.; Annandale, E.; Arthur, A.; Harvey, J.; Hsu, R.; Katbamna, S.; Olsen, R.; Smith, L.; et al. Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2006, 6, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brein, R.; Hunt, K.; Hart, G. ‘It’s caveman stuff, but that is to a certain extent how guys still operate’: Men’s accounts of masculinity and help seeking. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 61, 503–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, O.; Grunfeld, E.A.; Hunter, M.S. A systematic review of the factors associated with delays in medical and psychological help-seeking among men. Health Psychol. Rev. 2015, 9, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidler, Z.E.; Dawes, A.J.; Rice, S.M.; Oliffe, J.L.; Dhillon, M.H. The role of masculinity in men’s help-seeking for depression: A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 49, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaeker, J.; Petrie, T.A. “Man up!”: Exploring intersections of sport participation, masculinity, psychological distress, and help-seeking attitudes and intentions. Psychol. Men Masc. 2019, 20, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, D.L.; Heimerdinger-Edwards, S.R.; Hammer, J.H.; Hubbard, A. “Boys Don’t Cry”: Examination of the Links Between Endorsement of Masculine Norms, Self-Stigma, and Help-Seeking Attitudes for Men From Diverse Backgrounds. J. Couns. Psychol. 2011, 58, 368–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimer, D.J.; Levant, R.F. The relation of masculinity and help-seeking style with the academic help-seeking behavior of college men. J. Mens. Stud. 2011, 19, 256–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primack, J.M.; Addis, M.E.; Syzdek, M.; Miller, I.W. The men’s stress workshop: A gender-sensitive treatment for depressed men. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2010, 17, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, I.H.C.; Bathje, G.J.; Kalibatseva, Z.; Sung, D.; Leong, F.T.; Collins-Eaglin, J. Stigma, mental health, and counseling service use: A person-centred approach to mental health stigma profiles. Psychol. Serv. 2017, 14, 490–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levant, K.; Kamaradova, D.; Prasko, J. Perspectives on perceived stigma and self-stigma in adult male patients with depression. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2014, 10, 1399–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topkaya, N. Gender, Self-Stigma, and Public Stigma in Predicting Attitudes toward Psychological Help-Seeking. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 2014, 14, 480–487. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1038737 (accessed on 24 June 2020). [CrossRef]

- Clement, S.; Schauman, O.; Graham, T.; Maggioni, F.; Evans-Lacko, S.; Bezborodovs, N.; Morgan, C.; Rüsch, N.; Brown, J.S.; Thornicroft, G. What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychol. Med. 2015, 45, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levant, R.F.; Stefanov, D.G.; Rankin, T.J.; Halter, M.J.; Mellinger, C.; Williams, C.M. Moderated path analysis of the relationships between masculinity and men’s attitudes toward seeking psychological help. J. Couns. Psychol. 2013, 60, 392–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shepherd, C.B.; Rickard, K.M. Drive for muscularity and help-seeking: The mediational role of gender role conflict, self-stigma, and attitudes. Psychol. Men Masc. 2012, 13, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A. Using celebrities in abnormal psychology as teaching tools to decrease stigma and increase help seeking. Teach. Psychol. 2016, 43, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, C.E.; Himelein, M.J. Putting the person back into psychopathology: An intervention to reduce mental illness stigma in the classroom. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2008, 43, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swami, V. Mental health literacy of depression: Gender differences and attitudinal antecedents in a representative British sample. PLoS ONE 2014, 7, e49779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, S.M.; Wright, A.; Harris, M.G.; Jorm, A.F.; McGorry, P.D. Influence of gender on mental health literacy in young Australians. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2006, 40, 790–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reavley, N.J.; McCann, T.V.; Jorm, A.F. Mental health literacy in higher education students. Early Interven. Psychiatry 2012, 6, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.A.; Neighbors, H.W.; Griffith, D.M. The Experience of Symptoms of Depression in Men vs. Women Analysis of the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. JAMA Psychiatry 2013, 70, 1100–1106. Available online: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapsychiatry/article-abstract/1733742 (accessed on 24 June 2020). [CrossRef]

- Möller-Leimkühler, A.M. Barriers to help-seeking by men: A review of sociocultural and clinical literature with particular reference to depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2002, 71, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hunt, K.; Nazareth, I.; Freemantle, N.; Petersen, I. Do men consult less than women? An analysis of routinely collected UK general practice data. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e003320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deeks, A.; Lombard, C.; Michelmore, J.; Teede, H. The effects of gender and age on health related behaviors. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliffe, J.L.; Han, C.S. Beyond workers’ compensation: Men’s mental health in and our of work. Am. J. Mens. Health 2014, 8, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaem, A.; Woods, M.; Macdonald, J.; Hughes, R.; Orchard, M. Engaging men in the health system: Observations from service providers. Aust. Health Rev. 2007, 31, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cochran, S.V.; Rabinowitz, F.E. Gender-sensitive recommendations for assessment and treatment of depression in men. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2003, 34, 132–140. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/buy/2003-02179-002 (accessed on 24 June 2020). [CrossRef]

- Vogel, D.L.; Epting, F.; Wester, S.R. Counselors’ perceptions of female and male clients. J. Couns. Dev. 2003, 81, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalik, J.R.; Good, G.E.; Tager, D.; Levant, R.F.; Mackowiak, C. Developing a taxonomy of helpful and harmful practices for clinical work with boys and men. J. Couns. Psychol. 2012, 59, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour-Smith, S.; Wetherell, M.; Phoenix, A. ‘My wife ordered me to come!’: A discursive analysis of doctors’ and nurses’ accounts of men’s use of general practitioners. J. Health Psychol. 2002, 7, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, C. Mental Health Statistics for England: Prevalence, Services and Funding; House of Commons Library Briefing: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Liddon, L.; Kingerlee, R.; Barry, J.A. Gender differences in preferences for psychological treatment, coping strategies, and triggers for help-seeking. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 57, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddon, L.; Kingerlee, R.; Seager, M.; Barry, J.A. What are the factors that make a male-friendly therapy? In The Palgrave Handbook of Male Psychology and Mental Health; Barry, J.A., Kingerlee, R., Seager, M., Sullivan, L., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 671–694. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick, S.; Robertson, S. Mental health and wellbeing: Focus on men’s health. Br. J. Nurs. 2016, 25, 1163–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, S.M.; Aucote, H.M.; Parker, A.G.; Alvarez-Jimenez, M.; Filia, K.M.; Amminger, G.P. Men’s perceived barriers to help seeking for depression: Longitudinal findings relative to symptom onset and duration. J. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinhardt, S.; Bischof, G.; Grothues, J.; John, U.; Meyer, C.; Rumpf, H.J. Gender differences in the efficacy of brief interventions with a stepped cared approach in general practice patients with alcohol-related disorders. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008, 43, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Walker, E.A.; Katon, W.J.; Russo, J.; Korff, M.V.; Lin, E.; Simon, G.; Bush, T.; Ludman, E.; Unützer, J. Predictors of outcomes in a primary care depression trial. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2000, 15, 859–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seager, M.; Barry, J.A. Positive Masculinity: Including Masculinity as a Valued Aspect of Humanity. In The Palgrave Handbook of Male Psychology and Mental Health; Barry, J.A., Kingerlee, R., Seager, M., Sullivan, L., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 105–122. [Google Scholar]

- Krumm, S.; Checchia, C.; Koesters, M.; Kilian, R.; Becker, T. Men’s views on depression: A systematic review and metasynthesis of qualitative research. Psychopathology 2017, 50, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englar-Carlson, M.; Kiselica, M.S. Affirming the strengths in men: A positive masculinity approach to assisting male clients. J. Couns. Dev. 2013, 91, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiselica, M.S.; Englar-Carlson, M. Identifying, affirming, and building upon male strengths: The positive psychology/positive masculinity model of psychotherapy with boys and men. Psychother. Theor. Res. Pract. Train. 2010, 47, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidler, Z.E.; Rice, S.M.; Ogrodniczuk, J.S.; Oliffe, J.L.; Dhillon, M.H. Engaging Men in Psychological Treatment: A Scoping Review. Am. J. Mens. Health 2018, 12, 1882–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erentzen, C.; Quinlan, J.A.; Mar, R.A. Sometimes you need more than a wingman: Masculinity, femininity, and the role of humor in men’s mental health help-seeking campaigns. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 37, 128–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulliver, A.; Griffiths, K.M.; Christensen, H. Barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking for young elite athletes: A qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry 2012, 12, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disabato, D.J.; Short, J.L.; Lameira, D.M.; Bagley, K.D.; Wong, S.J. Predicting help-seeking behavior: The impact of knowing someone close who has sought help. J. Am. Coll. Health 2018, 66, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowlands, G.; Sims, J.; Kerry, S. A lesson learnt: The importance of modelling in randomized controlled trials for complex interventions in primary care. Fam. Pract. 2005, 22, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sagar-Ouriaghli, I.; Brown, J.S.; Vinay, T.; Godfrey, E. Engaging Male Students with Mental Health Support: A Qualitative Focus Group Study. under review.

- American Psychological Association, Boys and Men Guidelines Group. APA Guidelines for Psychological Practice with Boys and Men. Available online: http://www.apa.org/about/policy/psychological-practice-boys-men-guidelines.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2020).

- The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, NICE Pathways. Available online: https://pathways.nice.org.uk/ (accessed on 5 June 2020).

- NHS Digitial, Psychological Therapies: Annual Report on the Use of IAPT Services—England 2015-16. Available online: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20180328133700/http://digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB22110 (accessed on 5 June 2020).

- Ryan, G.; Marley, I.; Still, M.; Lyons, Z.; Hood, S. Use of mental-health services by Australian medical students: A cross-sectional survey. Australas Psychiatry 2017, 25, 407–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, D.; Speer, N.; Hunt, J.B. Attitudes and beliefs about treatment among college students with untreated mental health problems. Psychiatr. Serv. 2012, 63, 711–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- River, J. Diverse and dynamic interactions: A model of suicidal men’s help seeking as it relates to health services. Am. J. Mens. Health 2018, 12, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickwood, D.J.; Mazzer, K.R.; Telford, N.R. Social influences on seeking help from mental health services, in-person and online, during adolescence and young adulthood. BMC Psychiatry 2015, 15, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; Van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyworth, C.; Epton, T.; Goldthorpe, J.; Calam, R.; Armitage, C.J. Acceptability, reliability, and validity of a brief measure of capabilities, opportunities, and motivations (“COM-B”). Br. J. Health Psychol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, F.; Atkins, L.; de Lusignan, S. Applying the COM-B behaviour model and behaviour change wheel to develop an intervention to improve hearing-aid use in adult auditory rehabilitation. Int. J. Audiol. 2016, 55, S90–S98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; Atkins, L.; West, R. The Behaviour Change Wheel: A Guide to Designing Interventions; Silverback Publishing: Great Britain, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, M.L.; Heffer, R.W.; Gresham, F.M.; Elliot, S.N. Development of a modified treatment evaluation inventory. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 1989, 11, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhon, M.; Cartwright, M.; Francis, J.J. Development of a theory-informed questionnaire to assess the acceptability of healthcare interventions: Application of pre-validation methods. In Proceedings of the UK Society of Behavioural Medicine Annual Scientific Meeting, Birmingham, UK, 12 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sekhon, M.; Cartwright, M.; Francis, J.J. Acceptability of healthcare interventions: An overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, C.S.; Scott, T.; Mather, A.; Sareen, J. Older adults’ help-seeking attitudes and treatment beliefs concerning mental health problems. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2008, 16, 1010–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, C.S.; Gekoski, W.L.; Knox, V.J. Age, Gender, and the Underutilization of Mental Health Services: The Influence of Help-seeking Attitudes. Aging Ment. Health 2006, 10, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parent, M.; Hammer, J.H.; Bradstreet, T.C.; Schwartz, E.N.; Jobe, T. Men’s Mental Health Help-Seeking Behaviors: An Intersectional Analysis. Am. J. Mens. Health 2018, 12, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kam, B.; Mendoza, H.; Masuda, A. Mental Health Help-Seeking Experience and Attitudes in Latina/o American, Asian American, Black American, and White American College Students. Int. J. Adv. Couns. 2019, 41, 492–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Cruz, L.F.; Kolvenbach, S.; Vidal-Ribas, P.; Jassi, A.; Llorens, M.; Patel, N.; Weinman, J.; Hatch, S.L.; Bhugra, D.; Mataix-Cols, D. Illness perception, help-seeking attitudes, and knowledge related to obsessive-compulsive disorder across different ethnic groups: A community survey. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2016, 51, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baams, L.; De Luca, S.M.; Brownson, C. Use of mental health services among college students by sexual orientation. LGBT Health 2018, 5, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verissimo, A.D.; Grella, C.E. Influence of gender and race/ethnicity on perceived barriers to help-seeking for alcohol and drug problems. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2018, 75, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.E.; Zane, N. Help-seeking intentions among Asian American and White American Students in Psychological Distress: Application of the Health Belief Model. Cultur. Divers. Ethnic. Minor. Psychol. 2016, 22, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors Influencing Help-Seeking | Factors Targeted in Previous Interventions: Systematic Reviews (MRC 1.1) | Theory Relating to Men’s Help-Seeking: Access to Care Model (MRC 1.2) | Modelling Process and Outcomes: Focus Groups (MRC 1.3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Help-seeking is not masculine | X | X | X |

| Public-stigma of help-seeking | X | X | X |

| Self-stigma of help-seeking | X | X | X |

| Difficulty identifying mental health symptoms | X | X | X |

| Unsure of treatment structure | X | X | X |

| Unfamiliarity with mental health services | X | X | X |

| Social support, support groups and occupational support | X | X | X |

| Current relationship with service provider (e.g., trust) | X | X | |

| Symptom severity (i.e., delay until symptoms are unmanageable) | X | X | |

| Preference for proactive therapies | X | X | |

| Availability of services (e.g., extended opening hours, during exams and freshers) | X | X | |

| Ability to expressing emotions/emotional competence | X | ||

| Structure of the intervention (i.e., formality and duration) | X | ||

| Past experience of help-seeking and current help-seeking attitudes | X | ||

| Fear and embarrassment of using mental health services (treatment stigma) | X | ||

| Treatment is too time consuming | X | ||

| Clinician difficulty in detecting male symptoms | X | ||

| Clinician biases towards men with mental health difficulties | X |

| Capability: The Individual’s Capacity to Engage in the Behaviour | Opportunity: All Factors Lying Outside the Individual That Make Performance of the Behaviour Possible or Prompt it | Motivation: All Brain Process That Energise the Direct Behaviour |

|---|---|---|

| Psychological | Physical | Reflective |

| Difficulty identifying mental health symptoms | Availability of services | Help-seeking is not masculine |

| Ability to express emotions/emotional competence | Structure of the intervention | Self-stigma of help-seeking |

| Unsure of treatment structure | Preference for proactive therapies (availability) | Past experience of help-seeking |

| Unfamiliarity with mental health services | Treatment is too time consuming | Current help-seeking attitudes |

| Symptom severity (increases awareness) | Treatment stigma | |

| Symptom severity (evaluation of symptoms) | ||

| Treatment is too time consuming (perception) | ||

| Preference for proactive therapies (evaluation) | ||

| Physical | Social | Automatic |

| Public stigma of help-seeking | ||

| Social support | ||

| Relationship with service provider | ||

| Clinician difficulty in detecting symptoms | ||

| Clinician biases |

| Factor | COM-B Domain | Intervention Function | BCTs | Intervention Component |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difficulty identifying mental health symptoms | Psychological Capability | Education | 2.2. Feedback on behaviour 5.1. Information about health consequences 5.3. Information about social and environmental consequences 5.6. Information about emotional consequences | Incorporate educational content that provides information about common mental health symptoms, their presentation, consequences of not seeking help, and use screening tools to assist students with self-identifying any current symptoms. This educational content can be delivered through a range of methods such as face-to-face classes, presentations, videos or educational leaflets. |

| Unsure of treatment structure | Psychological Capability | Education | 5.1. Information about health consequences 5.6. Information about emotional consequences | Provide information about how service referrals and assessments operate. This may include information pertaining to waiting lists and where the referral takes place. Outline the treatment structure such as the number of sessions, how long appointments last for, and the types of confidentiality across services. Information can be delivered through a range of methods including face-to-face classes, presentations, videos or educational leaflets. |

| Unfamiliar with mental health services | Psychological Capability | Education | 3.1. Social support (unspecified) 3.2. Social support (practical) | Explain and sign-post different mental health services and support options. This includes the names of different services, the types of support they would receive and the geographical location of such support. Information can be delivered through a range of methods including face-to-face classes, presentations, videos or educational leaflets. |

| Social support | Social Opportunity | Environmental Restructuring | 3.1. Social support (unspecified) | Advise students to talk to friends and family about their mental health or provide environments that are conducive to forming social relationships. Advice can be delivered though presentations, posters, videos or educational leaflets. |

| Preference for proactive therapies | Psychological Capability or Reflective Motivation | Environmental Restructuring | 1.2. Problem solving 1.4. Action planning 11.2. Reduce negative emotions | Incorporated self-management strategies such as relaxation, time management, problem solving, and action planning to resolve mental health difficulties. Such strategies can be delivered in face-to-face class sessions or group settings. Referral to (online) self-help materials or video resources may also be suitable. |

| Help-seeking is not masculine | Reflective motivation | Modelling | 6.2. Social comparison 9.1. Credible source 13.2. Framing/Re-framing | Use group settings to discuss how mental health can still be masculine (e.g., a sign of strength). Draw attention to male celebrities and male role models who have sought help and are successful. Alternatively, use posters, videos or leaflets to promote help-seeking as a masculine trait. |

| Self-stigma of seeking help | Reflective Motivation | Modelling | 6.2. Social comparison 13.2. Framing/Re-framing | Reframe help-seeking to be positive and provide examples of others with mental health difficulties and how seeking help improved their well-being. Reframing can be achieved through group discussions, presentations, leaflets, posters or videos. |

| Treatment-stigma | Reflective Motivation | Persuasion | 5.1. Information about health consequences 5.6. Information about emotional consequences | Outline the benefits of treatment and what can be achieved if engaged with. Draw particular attention to one’s well-being, reduction of symptoms, and increased functioning. Information can be delivered through a range of methods including face-to-face classes, presentations, videos or educational leaflets. |

| Structure of the intervention | Physical Opportunity | Environmental Restructuring | NA | Create a male-only space for students to drop-in to as opposed to a formal intervention. Here, this drop-in space could be more attractive to male students and make the intervention less time consuming. Physical spaces that have a central theme (e.g., sports or arts and crafts) are likely to appeal to male students. However, online male spaces (e.g., gaming) may provide a similar opportunity. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sagar-Ouriaghli, I.; Godfrey, E.; Graham, S.; Brown, J.S.L. Improving Mental Health Help-Seeking Behaviours for Male Students: A Framework for Developing a Complex Intervention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4965. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17144965

Sagar-Ouriaghli I, Godfrey E, Graham S, Brown JSL. Improving Mental Health Help-Seeking Behaviours for Male Students: A Framework for Developing a Complex Intervention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(14):4965. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17144965

Chicago/Turabian StyleSagar-Ouriaghli, Ilyas, Emma Godfrey, Selina Graham, and June S. L. Brown. 2020. "Improving Mental Health Help-Seeking Behaviours for Male Students: A Framework for Developing a Complex Intervention" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 14: 4965. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17144965

APA StyleSagar-Ouriaghli, I., Godfrey, E., Graham, S., & Brown, J. S. L. (2020). Improving Mental Health Help-Seeking Behaviours for Male Students: A Framework for Developing a Complex Intervention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(14), 4965. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17144965