Abstract

Adverse events are common in healthcare. Three types of victims of patient-related adverse events can be identified. The first type includes patients and their families, the second type includes healthcare professionals involved in an adverse event and the third type includes healthcare organisations in which an adverse event occurs. The purpose of this integrative review is to synthesise knowledge, theory and evidence regarding action after adverse events, based on literature published in the last ten years (2009–2018). In the studies critically evaluated (n = 25), key themes emerged relating to the first, second and third victim elements. The first victim elements comprise attention to revealing an adverse event, communication after an event, first victim support and complete apology. The second victim elements include second victim support types and services, coping strategies, professional changes after adverse events and learning about adverse event phenomena. The third victim elements consist of organisational action after adverse events, strategy, infrastructure and training and open communication about adverse events. There is a lack of comprehensive models for action after adverse events. This requires understanding of the phenomenon along with ambition to manage adverse events as a whole. When an adverse event is identified and a concern expressed, systematic damage preventing and ameliorating actions should be immediately launched. System-wide development is needed.

1. Introduction

Adverse events (AEs) are inevitable in nursing and healthcare [1,2]. Even where best professional care exists, most treatments or investigations have the potential to cause harm [3]. Although the culture and system of a healthcare organisation (HCO) may be well developed, AEs will happen because of human factors and HCOs being complex adaptive systems, always changing and evolving. Thus, comprehensive preparation is important both to minimise harm to victims and to maintain the functionality of HCOs. In organisations with positive patient safety cultures professionals can speak openly about issues and events without fear of blame or punishment. Managers promote safety and reporting of AEs is supported and organisational learning occurs [1].

An AE is defined as an unintended or unexpected incident which causes harm to a patient and may lead to temporary or permanent disability [1,4]. Approximately every tenth patient in hospital suffers such events [5]. A quarter of these events in Europe are healthcare-associated infections; other AE types include medication errors, surgical errors, diagnostic errors, medical device failures or failure to act on test results [6]. Nurses and healthcare professionals often witness or are involved in AEs [2,7,8]. In healthcare, AEs can, at worst, cause catastrophic consequences [1]. It is clear that taking action after an AE has occurred is as important as prevention. About half of physicians say that involvement in AE increases stress in their work [9]. Many of the second victims seek support from family, colleagues or supervisor [10]. About 10% agree that organisations support them in coping with AEs [9].

Three kinds of victims of AEs can be identified. The “first victims” are conceptualised as patients and their families. Patients can suffer from an AE in two ways: first from direct harm caused and then from the way the event is handled [1]. The “second victims”, a concept originally introduced by Wu [11], are healthcare providers, including physicians, nurses, allied clinicians, support personnel, students and volunteers [12], who have been involved in a patient related AE and subsequently experience emotional or physical distress, thus becoming a victim themselves [13,14]. The phenomenon is quite common: the prevalence of second victim suffering is anticipated to be approximately 30%, varying from 10.4% to 43.3% [15]. Ninety per cent of healthcare professionals reported suffering at least one physical or psychosocial “second victim” symptom [16]. The “third victims” are healthcare organisations in which the AE occurs [17]. The impact on third victims can also be considerable, as AEs may create an organisational crisis leading to long-term business difficulties [18].

The effects of an AE on first, second and third victims include health-related, functional and economic consequences. These are interrelated and can cause significant costs. Both the first and second victims may suffer emotional and psychological, physical, financial and livelihood consequences [19]. In addition, second victims can face professional consequences, including concerns regarding the performance of their work [12,15,20,21,22]. Healthcare professionals may also experience difficulties working in an environment where AEs have occurred [23,24]. Consequences for third victims relate to effectiveness [12,19,20], reputation [19,25], legal [20] and economic issues [19]. Hence, these phenomena are crucial aspects to consider after an AE.

Managing the aftermath of AEs well can be assumed to have positive consequences for first and second victims’ health, behaviour and economic well-being. Considering HCOs as third victims, but also as responsible for the first and second victims, it is clear that where possible systematic prevention of first and second victim consequences, and appropriate care after an AE is crucial. Constructive actions after an event can have a positive impact on the safety culture, effectiveness of services and financial situation of the HCOs. In the US, the estimated cost of medical error in 2008 was USD 1 trillion, but patient safety improvements are estimated to have saved USD 28 billion [26]. Strategies to reduce the rate of AEs in the European Union alone could prevent more than 750,000 harm-inflicting medical errors per year. That means over 3.2 million fewer days of hospitalisation, 260,000 fewer incidents of permanent disability and 95,000 fewer deaths per year [27]. The economic consequences of AEs, and of how the events are handled, are therefore not limited to healthcare. For nations, increased absence from work, staff leaving the professions and deaths are examples of extreme consequences of AEs. Actions after AEs can be assumed to have serious short- and long-term, direct and indirect impact on individuals, the economy and society.

The purpose of this integrative review is to synthesise existing knowledge on actions following AEs in HCOs such as hospitals and primary care units. The aim is to identify the underlying elements required for damage preventing and ameliorating actions following AEs in order to provide direction for development and future investigation. The research question is: What are the key elements of action immediately after AEs in HCOs?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design of the Study

An integrative review approach was used following Whittemore and Knafl’s five stages: (1) the problem was identified; (2) the relevant literature published between 2009 and 2018 was sought; (3) the screened data were evaluated using a 10-item tool; (4) the eligible data were analysed using inductive content analysis; and (5) the findings are presented in tables [28]. In addition, the checklist of the Preferred Reporting Items Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) Statement (2009) was used to guide the review [29].

2.2. Search Strategy

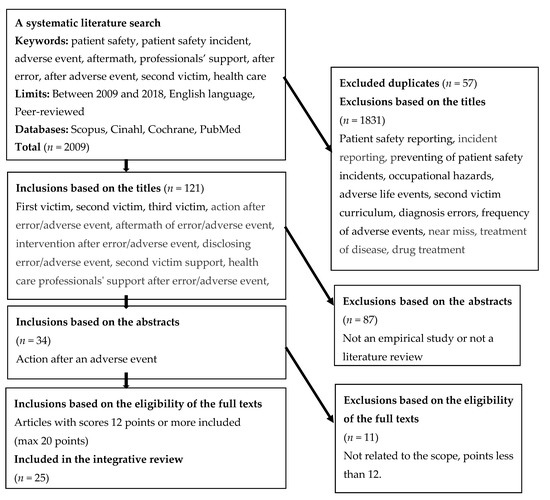

The databases Scopus, CINAHL, Cochrane and PubMed were searched for relevant articles. Boolean search methods were used to retrieve articles related to action after adverse events in healthcare such follows: “adverse event” AND “disclosure” OR “aftermath”, “adverse event” AND “professional’ support”, “healthcare” AND “second victim”, “healthcare” AND “after error”.

The search, for example, from Scopus included search terms “adverse event” AND “aftermath” OR “disclosure” with limits “in article, title, keywords”, “published 2009 to 2018”, “article or review”, “English language” and “in journals”. Articles were included if they reported on action after AE. Articles focusing on, for example, adverse drug reactions or AE reporting were excluded. Articles about AE reports were excluded when they were only about frequency of reports, or near misses and did not present the whole process from AE to disclosure. Search methods, inclusion and exclusion criteria and search outcomes are presented in Figure 1. Twenty-five research or review papers were found for inclusion in the data evaluation process.

Figure 1.

Systematic literature search process regarding action after adverse events.

2.3. Review and Quality Assessment Process

The search process was realised independently by the authors (ML and ST). Online discussions were held with other authors to share results and make decisions on next steps of the process.

The “quality” of papers was evaluated using a tool developed from an amalgamation of previous work [30,31,32,33] which was refined via international research group discussions. The evaluation areas included: (1) background; (2) aim and research questions; (3) sample; (4) data collection; (5) data analysis; (6) results; (7) ethical issues; (8) reliability; and (9) usefulness of the results. After discussing relevant evaluation areas for a comprehensive quality assessment, the research group added a further area: (10) strengths and limitations. Each evaluation area was scored from 0 to 2 points using the following criteria: (0) does not meet the aim or lacks data; (1) inaccurate or superficial; and (2) relevant and presented systematically. With 10 evaluation areas and a maximum of 2 points for each area, the range of the scores for a study varied from 0 to 20 points. Anything below 12 points was excluded due to low quality.

The articles retrieved were distributed evenly, and two researchers independently scored each paper using the tool. Total scores for each paper were compared and the content, importance, face validity and quality of each paper discussed. Where differences of three points or more were present, each sub-element score was discussed, and a third research team member acted as a moderator to arrive at a consensus. Cohens’ Kappa was calculated to test interrater reliability (κ = 0.83).

2.4. Data Analysis

The results of the studies retrieved were analysed using inductive content analysis [34]. First, the studies were read several times and listed in a table to gain an understanding of the whole and the characteristics of the actions taken after an AE. The data reduction phase included extraction of the data into a manageable framework. The aims of the study, research methods, findings, scores and scope of the action after AEs were presented. Then, the data were open coded, abstracted and categorised using content-characteristic words. Sub-categories were developed and discussed in the international research group. Sub-categories were further grouped into categories describing management of action after AEs. Care was taken not to double count data from individual studies duplicated in literature reviews.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristic for the Studies

The papers retrieved (n = 25) were published between 2009 and 2018 (Table 1). The largest numbers of papers were published in 2015 (n = 5) and 2018 (n = 5) and were from the USA (n = 12). Various methodologies were present: quantitative (n = 10), qualitative (n = 8), multiple methods (n = 2) and literature reviews (n = 5). The quality scores of the papers varied from 12 to 20 points, with a mean of 15.9 and standard deviation 2.1. The majority (n = 21) of papers were about second victim phenomenon and less attention was given to first (n = 6) and third victim phenomena (n = 4). One paper encompassed both first and second victims, three included both second and third “victims” and one paper covered all three “victims”.

Table 1.

Studies investigating action after adverse event.

3.2. Key Elements of Responses and Action after AEs Bulleted Lists Look Like This

Actions following AEs were comprised of three themes, namely first victims, second victims and third victims, with empathic and ethical communication, support services, complete apology and training and learning as cross-cutting elements.

The theme of action for first victims was comprised of four elements: attention in revealing an AE, communication after AEs, first victim support and complete apology (Table 2). Patients and families [19] and healthcare providers [35,36] alike were often afraid of speaking up. Empathic, ethical and open communication played an important role overall; the quality of the communication seemed to either empower or disempower patients and their families [19,37,38,39]. In many cases, patients are not informed about AEs [40]. Support for first victims was addressed primarily as a lack or neglect of emotional support [36,39] and compensation support [35]. Apologising was an important element after experiencing an AE [19,34,37,38]. First victims perceived the apology as an integrative process, where the style and the presenter of the apology, whether healthcare provider or organisation, played an important role. Expressing empathy, giving honest information about the AE, taking responsibility and learning from the event were crucial to the apology process.

Table 2.

“Action after adverse events” regarding first, second and third victim elements.

The action for second victims theme consisted of the following elements: second victim support types, coping strategies, support protocols, changes after AEs and learning about AE phenomena (Table 2). Support types consisted of informal [12,15,41,42,43,44,45], formal [15,23,25,40,41,46,47] and emotional [22,42,44,45,46] support for second victims. Healthcare providers have indicated informal peer support as important [20,41,42,49,50], but sensitive. The support can be destroyed, for example, by blaming, gossiping and silence [46]; thus, it is important to pay special attention to non-blaming, open and supportive communication. Formal support was not a certainty and was not offered in all cases [12,25,42,46,47]. The importance of emotional second victim support was clear and could be provided for all those involved, for individuals or groups [43,49,50]. Second victim coping strategies related to the individuality of strategies [12,49], emotional support [41,47,49,51] and problem solving [47,49].

The second victim support services comprised availability [11,24,25,41,44], counselling support [36,41,44], time away support [41,44,45] and open disclosure support [37,43,44]. Changes that second victims make after an AE can include defensive and constructive changes [50]. It was also found that learning about AEs [47], the second victim phenomenon and learning to communicate about AEs are important for staff members [12,44,48].

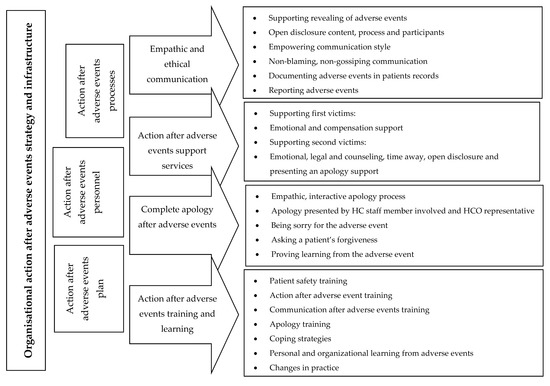

The action for the third victims theme consisted of organisational strategy and infrastructure [20,46,49], which was divided into action after adverse events plan [12,25,52], personnel [36,37,42,46,52] and processes [20,36,52] subthemes (Figure 2). The key elements of the subthemes were:

Figure 2.

“Action after adverse events” in healthcare organisations.

- emphasising open, empathic communication (for example, open disclosure) and each staff member’s responsibility for their empowering communication style [25,37,42];

- action after AE support services for first and second victims (for example, emotional support) [42,44,47,49]; and

- action after AE training and learning for managers and staff members [15,19,52].

4. Discussion

The results of this integrative literature review demonstrate how complex and multi-layered the phenomenon “action after AE” is and how this topic has gained attention in international research and healthcare development work. Previous studies have concentrated more on a single perspective regarding actions after AEs, while, in this integrative review, a more holistic view is presented. Key themes emerged relating to victims of AEs: first, second and third victim elements, with empathetic, effective communication, support services, complete apology and training and learning, as cross-cutting elements.

The first victim theme comprised attention to revealing an AE, communication after an event, first victim support and complete apology. The second victim theme included second victim support types, coping strategies, support services, changes after AEs and learning about AE phenomena. The third victim theme consisted of organisational action after AEs, strategy, infrastructure and training and open communication about AEs. These three themes interweave tightly together, and we approach the themes from a healthcare organisation’s perspective to outline the needs of first and second victims and how HCOs could respond to these. In this integrative review, second victim support programs were under development work. For example, Scott et al. designed “A Framework of Caring: The Scott Three-Tiered Interventional Model of Support”, which features: (Tier 1) unit level support; (Tier 2) trained peer supporters and patient safety and risk management resources; and (Tier 3) an expedited referral network with specialist support [12]. Indeed, a similar kind of support program could also benefit first victims.

Second victim support programs can be assumed to support first victims as well through better preparation of nurses and healthcare providers. However, it could be argued that more comprehensive first victim support programs are also needed. Attention to revealing an AE, open and emphatic communication and complete, authentic apology to, and support of, first victims were essential after AEs. For example, the apology policy of the HCOs seemed to be fragmented and often defensive. First victims highlighted the importance of an empathic, interactive process, where a sincere apology is expressed not just by an individual healthcare provider, but responsibility on the part of the HCO is accepted as well [53,54]. First victims implied that in some situations they might forgive, but it was unclear if forgiveness was asked for [35]. Here, an interactive support program could be beneficial for all victims, including nursing and healthcare students. For instance, first victims wanted the apology to include information about how the HCO would learn from the AE and make changes [19,35]. First victims had often lost trust in HCOs [19]. Open discussion about what went wrong, and why, can be the first step to understanding and forgiveness [55]. One reason for a loss of trust may be a lack of transparency after AE [56]. First victims should be convinced that everything possible is being done to avoid a similar situation in the future. If the apology included a convince of systematic, organisational level learning from the AE, the professionals involved may feel supported when discussing AEs with patients, peers and managers [57]. From the literature reviewed changes appear needed at the individual, team, unit and organisational levels. The results suggested a need for holistic approaches to managing AEs.

Safe, systematic and clear “action plan after AEs” required an understanding of each stakeholder’s needs. AEs consist of complex systems of problems which often interact; thus, it is important to deal with the phenomenon as a whole. Indeed, even those not directly involved may have impact on the consequences of AEs. The strategy and infrastructure of HCOs are crucial to managing action after AEs as part of healthcare delivery. An “action after AE” strategy needs to include a comprehensive plan which attends to the interlinked complexity which often exists. Well-thought-through communication is required from everyone in HCOs: colleagues, managers and second victims as well. AEs are very sensitive events that can have long-term consequences [12,15,19,20,24]. Thus, communication is fundamental to occupational and patient safety.

Organisational “action after AEs” infrastructure needed to have appointed personnel, clear support and learning infrastructure and clear processes. It was also important that the process and content of open disclosure are included in the management of the events. Emphatic, support and respect by colleagues is needed after AE so that healthcare professionals still feel competent to do their job [20]. With these actions, HCOs may be able to ameliorate the severe consequences for all victims, such as effectiveness of HCOs [12,19,20], economic issues [19] and reputation [19,25]. Nurses and healthcare professionals suffer when involved in AEs, may fear reporting events [48,58,59,60] and experience difficulties working in an environment where AEs have happened [23]. Being comprehensively prepared is important [58] both to minimise harm to all victims and for the functionality of healthcare systems.

Mira et al. found that many patients are not informed at all about AE. This may be because HCPs are afraid for their professional future, or because they do not have competence to honestly tell a patient what has happened [38,40,51]. A shortage of skill and resource lack of competence seems to be one barrier to developing organisational support programs after AE [50]. It is important not to forget the first victims outside this support. It is also good to recognise that first victims have much information about AEs to provide for organisational learning [38,39]. Crucial for this is that action after AE education is included in professional and continuing healthcare programme [33].

The strengths of this study include an international researcher group involved with strong patient safety research, management and education experience. For example, the data evaluation was conducted in two groups. The quality of the research papers was evaluated with an instrument used in an integrative review. Agreement among authors was measured by Cohen’s kappa (κ = 0.411), which can be interpreted as moderate [60]. Limitations include the method itself. Only peer reviewed research papers were used in this review. National or international guidelines and protocols about disclosing adverse events were omitted. The search strategy may have affected the number of different victim phenomena found vary. Combining different methodologies such as qualitative, quantitative and literature reviews can be difficult due to diverse ontological and epistemological underpinnings, which some may view as causing bias [28]. Team discussions regarding key features of the papers were utilised to assist in clarifying the quality of the studies and the main emergent points from each paper. Close attention was also given to the avoidance of double counting in order to avoid “skewing” the findings. The PRISMA statement was used to guide the writing of the review [29].

5. Conclusions

It is inevitable that AEs will occur in healthcare organisations, impacting on individual, team, unit, organisation and national levels. When an AE is identified and a concern expressed, immediate and comprehensive action should be taken. This requires trying to understand the whole phenomenon in its complexity, an ambition to manage AEs and a “just restorative” culture [61] that enables it. System-wide developments are needed regarding action after AEs, along with the implementation of evidence-based organisational infrastructures and strategies which could ameliorate the suffering of patients, their families and healthcare providers, as well as help healthcare organisations (and ultimately nations) to use resources effectively. For this developing, more research about patients’ and their families’ needs as well as organisations’ needs is required. Tight collaboration is needed between policy-makers, nursing and healthcare managers and educators in order to develop such systems and the necessary culture [62]. Only then will all victims receive appropriate support after AEs. We also suggest that future education, research, policy and practice developments should incorporate a move to a more balanced approach incorporating both Safety 1 (learning from failure) and Safety 2 (learning from how things typically go right) perspectives [61]. At the national level, social and healthcare ministries are responsible for planning, guidance and implementation of health and social policy to safeguard people’s ability to work and function. International collaboration between governments is needed to standardise studies concerning first, second and third victim phenomenon. Governments should build a network of researchers and healthcare managers for developing the study protocols and shared understanding of developing first, second and third victim support system in healthcare organisations. Such a move may assist in the development of “restorative just cultures” in HCOs and more holistic approaches to actions after AEs for the benefit of all “victims”.

Author Contributions

M.L. and S.T. conducted the literature search and evaluation of articles, and were major contributors to the manuscript. A.S., M.F.V.M., P.P., and H.T. participated in evaluation of articles and writing the manuscript. A.M.S.-a. and J.K. took part in manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The sixth author would like to thank INVEST Research Flagship funded by the Academy of Finland Flagship Programme (decision number: 320162).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Vincent, C. Patient Safety, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Van Gaal, B.G.; Schoonhoven, L.; Mintjes-de Groot, J.A.; Defloor, T.; Habets, H.; Voss, A. Concurrent incidence of adverse events in hospitals and nursing homes. J. Nurs. Sch. 2014, 46, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disclosure Working Group. Canadian Disclosure Guidelines: Being Open and Honest with Patients and Families [Internet]; Canadian Patient Safety Institute: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2011; Available online: http://www.patientsafetyinstitute.ca/en/toolsResources/disclosure/Documents/CPSI%20Canadian%20Disclosure%20Guidelines.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2018).

- World Health Organization. Conceptual Framework for the International Classification for Patient Safety (v.1.1) [Internet]; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009; Available online: http://www.who.int/patientsafety/taxonomy/icps_full_report.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2018).

- De Vries, E.N.; Ramrattan, M.A.; Smorenburg, S.M.; Gouma, D.J.; Boermeester, M.A. The incidence and nature of in-hospital adverse events: A systematic review. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2008, 7, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. Patient Safety and Quality of Care Working Group. Key Findings and Recommendations on Reporting and Learning Systems for Patient Safety Incidents across Europe [Internet]; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014; Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/health//sites/health/files/patient_safety/docs/guidelines_psqcwg_reporting_learningsystems_en.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2018).

- Andersson, Å.; Frank, C.; Willman, A.M.L.; Hansebo, G. Adverse events in nursing: A retrospective study of reports of patient and relative experiences. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2015, 62, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlberg, Å.; Sachs, M.A.; Johannesson, K.B.; Hallberg, G.; Jonsson, M.; Skoog Svanberg, A.; Högberg, U. Self-reported exposure to severe events on the labour ward among Swedish midwives and obstetricians: A cross-sectional retrospective study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2017, 65, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaghy, C.; Doherty, R.; Irwin, T. Patient safety: A culture of openness and supporting staff. Surgery 2018, 36, 09–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edrees, H.; Connors, C.; Paine, L.; Norvell, M.; Taylor, H.; Wu, A.W. Implementing the RISE second victim support programme at the Johns Hopkins Hospital: A case study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.W. Medical error: The second victim: The doctor who makes the mistake needs help too. BMJ 2000, 320, 726–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.D.; Hirschinger, L.E.; Cox, K.R.; McCoig, M.M.; Hahn-Cover, K.; Epperly, K.M.; Epperly, K.M.; Phillips, E.C.; Hall, L.W. Caring for our own: Deploying a systemwide second victim rapid response team. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2010, 36, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, L.W.; Scott, S.D. The second victim of adverse health care events. Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 2012, 47, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, J.E.; Agan, D.L.; Chakedis, S.; Skrobik, Y. Workplace blame and related concepts: An analysis of three case studies. Chest 2015, 148, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seys, D.; Wu, A.W.; Van Gerven, E.; Vleugels, A.; Euwema, M.; Panella, M.; Scott, S.D.; Conway, J.; Sermeus, W.; Vanhaecht, K. Health care professionals as second victims after adverse events: A systematic review. Eval. Health Prof. 2013, 36, 135–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamadi-Bolbanabad, A.; Morade, G.; Piroozi, B.; Safari, H.; Asadi, H.; Nasseri, K.; Mohammadi, H.; Afkhamzadeh, A. The second victims’ experience and related factors among medical staff. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag 2019, 12, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, L. “Second victim” casualties and how physician leaders can help. Physician Exec. 2014, 40, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Conway, J.; Federico, F.; Stewart, K.; Campbell, M. Respectful Management of Serious Clinical Adverse Events, 2nd ed.; [Internet]; IHI Innovation Series White Paper; Institute for Healthcare Improvement: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011; Available online: http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/IHIWhitePapers/RespectfulManagementSeriousClinicalAEsWhitePaper.aspx (accessed on 23 November 2018).

- McVeety, J.; Keeping-Burke, L.; Harrison, M.B.; Godfrey, C.; Ross-White, A. Patient and family member perspectives of encountering adverse events in health care: A systematic review. JBI Database Syst. Rev. Implement. Rep. 2014, 12, 315–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullström, S.; Sachs, M.A.; Hansson, J.; Øvretveit, J.; Brommels, M. Suffering in silence: A qualitative study of second victims of adverse events. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2013, 23, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kable, A.K.; Spigelman, A.D. Why clinicians involved with adverse events need much better support. Int. J. Health Gov. 2018, 23, 312–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kable, A.; Kelly, B.; Adams, J. Effects of adverse events in health care on acute care nurses in an Australian context: A qualitative study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2018, 20, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzan, K.D.; Merandi, J.; Morvay, S.; Mirtallo, J. Implementation of a “second victim” program in a pediatric hospital. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2015, 72, 563–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriquez, J.; Scott, S.D. When Clinicians Drop Out and Start Over after Adverse Events. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2018, 44, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mira, J.J.; Carrillo, I.; Lorenzo, S.; Ferrús, L.; Silvestre, C.; Pérez-Pérez, P.; Olivera, G.; Iglesias, F.; Zavala, E.; Maderuelo-Fernández, J.; et al. The aftermath of adverse events in Spanish primary care and hospital health professionals. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slawomirski, L.; Auraaen, A.; Klazinga, N. The Economic of Patient Safety. Strengthening a Value-Based Approach to Reducing Patient Harm at National Level; OECD: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. Patient Safety, Data and Statistics. Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/Health-systems/patient-safety/data-and-statistics (accessed on 12 November 2019).

- Whittemore, R.; Knafl, K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 52, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; for the PRISMA group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawker, S.; Payne, S.; Kerr, C.; Powell, J. Appraising the evidence: Reviewing disparate data systematically. Qual. Health Res. 2002, 12, 1284–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokelainen, M.; Turunen, H.; Tossavainen, K.; Jamookeeah, D.; Coco, K. A systematic review of mentoring nursing students in clinical placements. J. Clin. Nurs. 2011, 20, 2854–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, P.; Steven, A.; Howe, A.; Sheikh, A.; Ashcroft, D.; Smith, P.; on behalf of Patient Safety Education Study Group. Learning about patient safety: Organizational context and culture in the education of health care professionals. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2010, 15, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tella, S.; Liukka, M.; Jamookeeah, D.; Smith, N.J.; Partanen, P.; Turunen, H. What do nursing students learn about patient safety? An integrative literature review. J. Nurs. Educ. 2014, 53, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Turunen, H.; Bondas, T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2013, 15, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, X.; Itoh, K. Patient views and attitudes to physician’s actions after medical errors in China. J. Patient Saf. 2012, 8, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mira, J.J.; Lorenzo, S.; Carrillo, I.; Ferrús, L.; Pérez-Pérez, P.; Iglesias, F.; Silvestre, C.; Olivera, G.; Zavala, E.; Nuño-Solinís, R.; et al. on behalf of the Research Group on Second and Third Victims. Interventions in health organisations to reduce the impact of adverse events in second and third victims. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, R.; Iedema, R.; Piper, D.; Manias, E.; Williams, A.; Tuckett, A. Disclosing clinical adverse events to patients: Can practice inform policy? Health Expect. 2010, 13, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, D.; Espin, S. Views of children, parents, and health-care providers on pediatric disclosure of medical errors. J. Child Health Care 2018, 22, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hågensen, G.; Nilsen, G.; Mehus, G.; Henriksen, N. The struggle against perceived negligence. A qualitative study of patients’ experiences of adverse events in Norwegian hospitals. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mira, J.J.; Lorenzo, S.; Carrillo, I.; Ferrús, L.; Silvestre, C.; Astier, P.; Iglesias-Alonso, F.; Maderuelo-Fernández, J.Á.; Pérez-Pérez, P.; Torijano, M.L.; et al. Lessons learned for reducing the negative impact of adverse events on patients, health professionals and healthcare organizations. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2017, 29, 450–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treiber, L.A.; Jones, J.H. The second victims of infusion therapy-related medication errors. J. Infus. Nurs. 2018, 41, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlison, J.D.; Scott, S.D.; Browne, E.K.; Thompson, S.G.; Hoffman, J.M. The Second Victim Experience and Support Tool: Validation of an organizational resource for assessing second victim effects and the quality of support resources. J. Patient Saf. 2017, 13, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edrees, H.H.; Paine, L.A.; Feroli, E.R.; Wu, A.W. Health care workers as second victims of medical errors. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2011, 121, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrús, L.; Silvestre, C.; Olivera, G.; Mira, J.J. Qualitative study about the experiences of colleagues of health professionals involved in an adverse event. J. Patient Saf. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joesten, L.; Cipparrone, N.; Okuno-Jones, S.; DuBose, E.R. Assessing the perceived level of institutional support for the second victim after a patient safety event. J. Patient Saf. 2015, 11, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, E.J.; Baernholdt, M.; Hamric, A. Nurses’ experience of medical errors: An integrative literature review. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2013, 28, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, S.; Coldridge, L. ‘No man’s land’: An exploration of the traumatic experiences of student midwives in practice. Midwifery 2015, 31, 858–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.; Lawton, R.; Perlo, J.; Gardner, P.; Armitage, G.; Shapiro, J. Emotion and coping in the aftermath of medical error: A cross-country exploration. J. Patient Saf. 2015, 11, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seys, D.; Scott, S.; Wu, A.; Van Gerven, E.; Vleugels, A.; Euwema, M.; Panella, M.; Conway, J.; Sermeus, W.; Vanhaecht, K. Supporting involved health care professionals (second victims) following an adverse health event: A literature review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2013, 50, 678–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edrees, H.H.; Wu, A.W. Does one size fit all? Assessing the need for organizational second victim support programs. J. Patient Saf. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delacroix, S. Exploring the experience of nurse practitioners who have committed medical errors: A phenomenological approach. J. Am. Acad. Nurse Pract. 2017, 29, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Gerven, E.; Bruyneel, L.; Panella, M.; Euwema, M.; Sermeus, W.; Vanhaecht, K. Psychological impact and recovery after involvement in a patient safety incident: A repeated measures analysis. BMJ Open. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kachalia, A.; Bates, D.W. Disclosing medical errors: The view from the USA. Surgeon 2014, 12, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngson, G.G. Medical error and disclosure—A view from the U.K. Surgeon 2014, 4, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.W.; McCay, L.; Levinson, W.; Iedema, R.; Wallace, G.; Boyle, D.J.; McDonald, T.B.; Bismark, M.; Kraman, S.S.; Forbes, E.; et al. Disclosing adverse events to patients: International norms and trends. J. Patient Saf. 2017, 13, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, A.; Haraden, C.; Federico, F.; Lenoci-Edwards, J. A Framework for Safe, Reliable and Effective Care; White Paper; Institute for Healthcare Improvement and Safe & Reliable Healthcare: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brborovic, O.; Brborvic, H.; Nola, I.A.; Miloševic, M. Culture of blame—An ongoing burden for doctors and patient safety. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moumtzoglou, A. Factors impeding nurses from reporting adverse events. J. Nurs. Manag. 2010, 18, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujan, M. An organisation without a memory: A qualitative study of hospital staff perceptions on reorting and organisational learning for patient safety. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2015, 144, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochem. Med. (Zagreb) 2012, 22, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodward, S. Implementing Patient Safety: Addressing Culture, Conditions and Values to Help People Work Safely; Routledge, Tylor and Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow, J.M.; Gustavson, A.M.; Jones, J. Speaking up behaviours (safety voices) of healthcare workers: A metasynthesis of qualitative research. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 64, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).