Follower Dependence, Independence, or Interdependence: A Multi-Foci Framework to Unpack the Mystery of Transformational Leadership Effects

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theory and Research Question

2.1. Transformational Leadership

2.2. Multi-Foci Framework of Transformational Leadership Process

2.3. Follower Dependence upon the Leader ‘Focus’: The Role of Personal Identification with the Leader

2.4. Follower Independence from the Leader ‘Focus’: The Development of Psychological Empowerment

2.5. Follower Interdependence with the Leader ‘Focus’: Evolution of LMX

2.6. Juxtaposition of the Three Alternative ‘Foci’

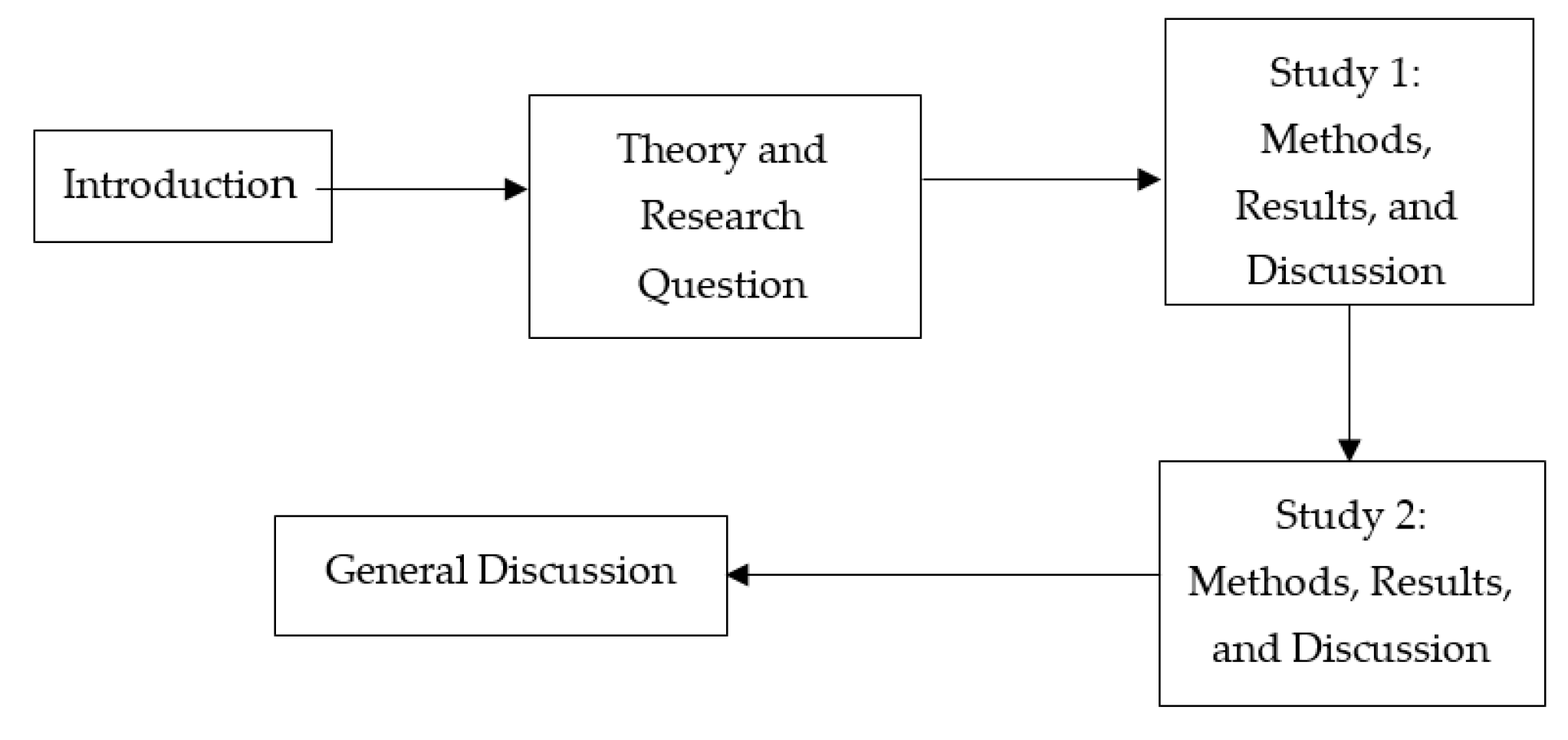

3. Overview of Present Research

3.1. Study 1: Methods

3.1.1. Participants and Procedures

3.1.2. Measures

3.1.3. Analytical Approach

3.2. Study 1: Results

3.2.1. CFAs

3.2.2. Testing the Research Question

3.3. Study 1: Discussion

3.4. Study 2: Methods

3.4.1. Participants and Procedures

3.4.2. Measures

3.4.3. Analytical Approach

3.5. Study 2: Results

3.5.1. CFAs

3.5.2. Testing the Research Question

3.6. Study 2: Discussion

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bass, B.M. Leadership and Performance beyond Expectations; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, J.M. Leadership; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, S.J.; Zhou, J. Transformational leadership, conservation, and creativity: Evidence from Korea. Acad. Manag. J. 2003, 41, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkman, B.L.; Chen, G.; Farh, J.-L.; Chen, Z.X.; Lowe, K.B. Individual power distance orientation and follower reactions to transformational leaders: A cross-level, cross-cultural examination. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 744–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triana, M.D.C.; Richard, O.C.; Yücel, I. Status incongruence and supervisor gender as moderators of the transformational leadership to subordinate affective organizational commitment relationship. Pers. Psychol. 2017, 70, 429–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Knippenberg, D.; Sitkin, S.B. A critical assessment of charismatic-transformational leadership research: Back to the drawing board? Acad. Manag. Ann. 2013, 7, 1–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottfredson, R.K.; Aguinis, H. Leadership behaviors and follower performance: Deductive and inductive examination of theoretical rationales and underlying mechanisms. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 558–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Iun, J.; Liu, A.; Gong, Y. Does participative leadership enhance work performance by inducing empowerment or trust? The differential effects on managerial and non-managerial subordinates. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 31, 122–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Bartol, K.M. Linking empowering leadership and employee creativity: The influence of psychological empowerment, intrinsic motivation, and creative process engagement. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dust, S.B.; Resick, C.J.; Mawritz, M.B. Transformational leadership, psychological empowerment, and the moderating role of mechanistic-organic contexts. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35, 413–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kark, R.; Shamir, B.; Chen, G. The two faces of transformational leadership: Empowerment and dependency. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Law, K.S.; Hackett, R.D.; Wang, D.; Chen, Z. Leader-member exchange as a mediator of the relationship between transformational leadership and followers’ performance and organizational citizenship behavior. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, J.E.; McNamara, G. From the editors: Publishing in “AMJ”—Part 2: Research design. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 657–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Spreitzer, G.M. Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 1442–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graen, G.B.; Uhl-Bien, M. Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. Leadersh. Q. 1995, 6, 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schriesheim, C.A.; Castro, S.L.; Cogliser, C.C. Leader-member exchange (LMX) research: A comprehensive review of theory, measurement, and data-analytic practices. Leadersh. Q. 1999, 10, 63–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Oh, I.-S.; Courtright, S.H.; Colbert, A.E. Transformational leadership and performance across criteria and levels: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of research. Group Organ. Manag. 2011, 36, 223–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryee, S.; Walumbwa, F.O.; Zhou, Q.; Hartnell, C.A. Transformational leadership, innovative behavior, and task performance: Test of mediation and moderation processes. Hum. Perform. 2011, 25, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Meyer, D.M.; Wang, P.; Wang, H.; Workman, K.; Christensen, A.L. Linking ethical leadership to employee performance: The roles of leader–member exchange, self-efficacy, and organizational identification. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2011, 115, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.R.; Berry, J.W. The presence of something or the absence of nothing: Increasing theoretical precision in management research. Organ. Res. Methods 2010, 13, 668–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Ven, A.H. Engaged Scholarship: A Guide for Organizational and Social Research; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M. Two decades of research and development in transformational leadership. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 1999, 8, 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Moorman, R.H.; Fetter, R. Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on followers’ trust in leader, satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Leadersh. Q. 1990, 1, 107–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conger, J.A.; Kanungo, R.N. Toward a behavioral theory of charismatic leadership in organizational settings. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1987, 12, 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbuto, J.E., Jr. Taking the charisma out of transformational leadership. J. Soc. Behav. Personal. 1997, 12, 689–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccolo, R.F.; Colquitt, J.A. Transformational leadership and job behaviors: The mediating role of core job characteristics. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, J.M. Two faces of charisma: Socialized and personalized leadership in organizations. In Charismatic Leadership; Conger, J.A., Kanungo, R.N., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1988; pp. 213–236. [Google Scholar]

- Shamir, B.; House, R.J.; Arthur, M.B. The motivational effects of charismatic leadership: A self-concept based theory. Organ. Sci. 1993, 4, 577–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H. Differentiation between Social Groups: Studies in the Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Academic Press: London, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Shamir, B.; Zakay, E.; Breinin, E.; Popper, M. Correlates of charismatic leader behavior in military units: Subordinates’ attitudes, unit characteristics, and superiors’ appraisals of leader performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1998, 41, 387–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukl, G. An evaluation of conceptual weakness in transformational and charismatic leadership theories. Leadersh. Q. 1999, 10, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhu, R.; Yang, Y. I warn you because I like you: Voice behavior, employee identifications, and transformational leadership. Leadersh. Q. 2010, 21, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-H.F.; Howell, J.M. A multilevel study of transformational leadership, identification, and follower outcomes. Leadersh. Q. 2012, 23, 775–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennis, W.G.; Nanus, B. Leaders; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Hartnell, C.A. Understanding transformational leadership-employee performance links: The role of relational identification and self-efficacy. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2011, 84, 153–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Hartog, D.N.; Belschak, F.D. When does transformational leadership enhance employee proactive behavior? The role of autonomy and role breadth self-efficacy. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Huang, J.-C.; Farh, J.-L. Employee learning orientation, transformational leadership, and employee creativity: The mediating role of employee creative self-efficacy. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 765–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Lange, P.A.M.; Rusbult, C.E. Interdependence theory. In Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology; Van Lange, P.A.M., Kruglanski, A.W., Higgins, E.T., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012; Volume 2, pp. 251–272. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, H.H.; Thibaut, J.W. Interpersonal Relations: A Theory of Interdependence; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.C.; Maslyn, J.M. Multidimensionality of leader-member exchange: An empirical assessment through scale development. J. Manag. 1998, 24, 43–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, D.; Deinert, A.; Homan, A.C.; Voelpel, S.C. Revisiting the mediating role of leader–member exchange in transformational leadership: The differential impact model. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2016, 25, 883–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulebohn, J.H.; Bommer, W.H.; Liden, R.C.; Brouer, R.L.; Ferris, G.R. A meta-analysis of antecedents and consequences of leader-member exchange: Integrating the past with an eye toward the future. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 1715–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, R.J.A. 1976 theory of charismatic leadership. In Leadership: The Cutting Edge; Hunt, J.G., Larson, L.L., Eds.; Southern Illinois University Press: Carbondale, IL, USA, 1977; pp. 189–207. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M. Bass and Stogdill’s Handbook of Leadership; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Avolio, B.J.; Bass, B.M. You can drag a horse to water but you can’t make it drink unless it is thirsty. J. Leadersh. Stud. 1998, 5, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Gibbons, T.C. Developing transformational leaders: A life span approach. In The Jossey-Bass Management Series. Charismatic Leadership: The Elusive Factor in Organizational Effectiveness; Conger, J.A., Kanungo, R.N., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1998; pp. 276–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Zhu, W.C.; Koh, W.; Bhatia, P. Transformational leadership and organizational commitment: Mediating role of psychological empowerment and moderating role of structural distance. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 951–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannah, S.T.; Schaubroeck, J.M.; Peng, A.C. Transforming followers’ value internalization and role self-efficacy: Dual processes promoting performance and peer norm-enforcement. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 252–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W.H. Transformational leadership and performance outcomes: Analyses of multiple mediation pathways. Leadersh. Q. 2017, 28, 385–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.C.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R. The wording and translation of research instruments. In Field Methods in Cross-Cultural Research; Lonner, W.J., Berry, J.W., Eds.; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1986; pp. 137–164. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schriesheim, C.A.; Neider, L.L.; Scandura, T.A. Delegation and leader-member exchange: Main effects, moderators, and measurement issues. Acad. Manag. J. 1998, 41, 298–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliese, P.D. Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: Implications for data aggregation and analysis. In Multilevel Theory, Research, and Methods in Organizations: Foundations, Extensions, and New Directions; Klein, K.J., Katherine, S.W.J., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 349–381. [Google Scholar]

- Bliese, P.D.; Hanges, P.J. Being both too liberal and too conservative: The perils of treating grouped data as though they were independent. Organ. Res. Methods 2004, 7, 400–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Lockwood, C.M.; Williams, J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2004, 39, 99–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preacher, K.J.; Zyphur, M.J.; Zhang, Z. A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychol. Methods 2010, 15, 209–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selig, J.P.; Preacher, K.J. Monte Carlo Method for Assessing Mediation: An Interactive Tool for Creating Confidence Intervals for Indirect Effects [Computer Software] 2008. Available online: http://www.quantpsy.org (accessed on 8 January 2017).

- Sobel, M.E. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociol. Methodol. 1982, 13, 290–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boal, K.B.; Bryson, J.M. Charismatic leadership: A phenomenological and structural approach. In International Leadership Symposia Series: Emerging Leadership Vistas; Lexington Books/D. C.; Hunt, J.G., Baliga, B.R., Dachler, H.P., Schriesheim, C.A., Eds.; Health and Com: Lexington, MA, USA, 1998; pp. 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Yukl, G. Managerial leadership: A review of theory and research. J. Manag. 1989, 15, 251–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, S.; Wooldridge, B. Dinosaurs or dynamos? Recognizing middle management’s strategic roles. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 1994, 8, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, J.; Hutchinson, S. Front-line managers as agents in the HRM-performance causal chain: Theory, analysis and evidence. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2007, 17, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacher, H.; Pearce, L.K.; Rooney, D.; McKenna, B. Leaders’ personal wisdom and leader–member exchange quality: The role of individualized consideration. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 121, 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernerth, J.B.; Armenakis, A.A.; Field, H.S.; Giles, W.F.; Walker, H.J. Leader–member social exchange (LMSX): Development and validation of a scale. J. Organ. Behav. 2007, 28, 979–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Baer, M.D.; Long, D.M.; Halvorsen-Ganepola, M.D.K. Scale indicators of social exchange relationships: A comparison of relative content validity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 99, 599–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.; Allen, N.J. Organizational citizenship behavior and workplace deviance: The role of affect and cognitions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonakis, J.; Bendahan, S.; Jacquart, P.; Lalive, R. On making causal claims: A review and recommendations. Leadersh. Q. 2010, 21, 1086–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, A.S.; Wang, H.; Xin, K.; Zhang, L.H.; Fu, P.P. Let a thousand flowers bloom: Variation of leadership styles among Chinese CEOs. Organ. Dyn. 2004, 33, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, R.; Janssen, O.; Shi, K. Transformational leadership and follower creativity: The mediating role of follower relational identification and the moderating role of leader creativity expectations. Leadersh. Q. 2015, 26, 286–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Hartog, D.N.; House, R.J.; Hanges, P.J.; Ruiz-Quintanilla, S.A.; Dorfman, P.W.; Abdalla, I.A.; Adetoun, B.S.; Aditya, R.N.; Agourram, H.; Akande, A.; et al. Culture specific and cross-culturally generalizable implicit leadership theories: Are attributes of charismatic/transformational leadership universally endorsed? Leadersh. Q. 1999, 10, 219–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, R.J.; Shamir, B. Towards the integration of transformational, charismatic, and visionary theories. In Leadership Theory and Research: Perspectives and Directions; Chemers, M.M., Ayman, R., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, M.E. What is Charisma? Br. J. Sociol. 1973, 24, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowold, J.; Heinitz, K. Transformational and charismatic leadership: Assessing the convergent, divergent and criterion validity of the MLQ and the CKS. Leadersh. Q. 2007, 18, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Yammarino, F.J. Introduction to, and overview of, transformational and charismatic leadership. In Transformational and Charismatic Leadership: The Road Ahead, 10th ed.; Avolio, B.J., Yammarino, F.J., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2013; Volume 5, pp. xxvii–xxxiii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, J.M.; Shamir, B. The role of followers in the charismatic leadership process: Relationships and their consequences. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2005, 30, 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, T.; Dietz, J.; Antonakis, J. Leadership process models: A review and synthesis. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1726–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorinkova, N.M.; Pearsall, M.J.; Sims, H.P. Examining the differential longitudinal performance of directive versus empowering leadership in teams. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 573–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer, A. Theory and Political Charisma. Comp. Stud. Soc. Hist. 1974, 16, 150–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.C.H.; Mak, W. Benevolent leadership and follower performance: The mediating role of leader–member exchange (LMX). Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2012, 29, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoch, J.E.; Bommer, W.H.; Dulebohn, J.H.; Wu, D. Do ethical, authentic, and servant leadership explain variance above and beyond transformational leadership? A meta-analysis. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 501–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G.H. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind; McGraw-Hill: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Dulebohn, J.; Wu, D.; Liao, C.; Hoch, J.E. Transformational leadership and national culture: A meta-analysis across 36 nations. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X. The romance of motivational leadership: How do Chinese leaders motivate employees? In Handbook of Chinese Organizational Behavior: Integrating Theory, Research and Practice; Huang, X., Bond, M., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2012; pp. 184–208. [Google Scholar]

- Covey, S.R. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K.; Harrison, D.A. Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2005, 97, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.C.; Wayne, S.J.; Zhao, H.; Henderson, D. Servant leadership: Development of a multidimensional measure and multi-level assessment. Leadersh. Q. 2008, 19, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Gardner, W.L. Authentic leadership development: Getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 315–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| df | χ2 | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1: | ||||||

| 6-factor model | 215 | 520.56 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.08 | 0.06 |

| 5-factor model (identification and LMX collapsed to form one factor) | 220 | 558.21 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.08 | 0.06 |

| 5-factor model (identification and psychological empowerment collapsed to form one factor) | 220 | 630.80 | 0.88 | 0.86 | 0.09 | 0.06 |

| 5-factor model (LMX and psychological empowerment collapsed to form one factor) | 220 | 607.40 | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.09 | 0.06 |

| Study 2: | ||||||

| 6-factor model | 215 | 373.11 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.07 | 0.06 |

| 5-factor model (identification and LMX collapsed to form one factor) | 220 | 619.42 | 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.11 | 0.07 |

| 5-factor model (identification and psychological empowerment collapsed to form one factor) | 220 | 492.70 | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.09 | 0.07 |

| 5-factor model (LMX and psychological empowerment collapsed to form one factor) | 220 | 547.09 | 0.86 | 0.84 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| Variable | M | SD | α a | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | 5.55 | 5.82 | 5.04 | 5.42 | 3.38 | 5.47 | |||

| SD | 1.02 | 0.95 | 1.11 | 0.82 | 0.74 | 0.99 | |||

| α a | 0.97 | 0.90 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.96 | |||

| 1. TFL b | 5.70 | 0.71 | 0.94 | 0.58 ** | 0.42 ** | 0.28 ** | 0.21 * | 0.26 ** | |

| 2. Personal identification | 5.81 | 0.83 | 0.87 | 0.73 ** | 0.56 ** | 0.45 ** | 0.36 ** | 0.41 ** | |

| 3. LMX c | 5.86 | 0.83 | 0.82 | 0.75 ** | 0.75 ** | 0.29 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.29 ** | |

| 4. Psychological empowerment | 5.44 | 0.72 | 0.81 | 0.40 ** | 0.46 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.18 * | 0.11 | |

| 5. Task performance | 3.51 | 0.63 | 0.90 | 0.15 * | 0.17 ** | 0.16 * | 0.20 ** | 0.70 ** | |

| 6. OCB d | 5.59 | 0.62 | 0.90 | 0.12 | 0.22 ** | 0.16 * | 0.13 * | 0.59 ** |

| Task Performance | OCB | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI | 95% CI | |||||

| Point Estimate | Lower | Upper | Point Estimate | Lower | Upper | |

| Study 1 a | ||||||

| Indirect effects | Indirect effects | |||||

| Personal identification | 0.02 | −0.11 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.26 |

| LMX | 0.06 | −0.04 | 0.16 | 0.08 | −0.01 | 0.17 |

| Psychological empowerment | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.10 | −0.00 | −0.06 | 0.06 |

| Total indirect effects | 0.12 | −0.01 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.09 | 0.35 |

| Study 2 b | ||||||

| Indirect effects | Indirect effects | |||||

| Personal identification | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.12 |

| LMX | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.05 |

| Psychological empowerment | −0.01 | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.01 | −0.04 | 0.02 |

| Total indirect effects | 0.05 | −0.00 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.13 |

| Task Performance | OCB | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monte Carlo 95% CI | Monte Carlo 95% CI | |||||

| Point Estimate | Lower | Upper | Point Estimate | Lower | Upper | |

| Study 1 a | ||||||

| Indirect effects | Indirect effects | |||||

| Personal identification | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.27 |

| LMX | 0.06 | −0.03 | 0.16 | 0.08 | −0.01 | 0.18 |

| Psychological empowerment | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.11 | −0.00 | −0.06 | 0.06 |

| Study 2 b | ||||||

| Indirect effects | Indirect effects | |||||

| Personal identification | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.12 |

| LMX | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.05 |

| Psychological empowerment | −0.01 | −0.04 | 0.03 | −0.01 | −0.05 | 0.02 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Huang, X. Follower Dependence, Independence, or Interdependence: A Multi-Foci Framework to Unpack the Mystery of Transformational Leadership Effects. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4534. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124534

Lu Q, Liu Y, Huang X. Follower Dependence, Independence, or Interdependence: A Multi-Foci Framework to Unpack the Mystery of Transformational Leadership Effects. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(12):4534. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124534

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Qing, Yonghong Liu, and Xu Huang. 2020. "Follower Dependence, Independence, or Interdependence: A Multi-Foci Framework to Unpack the Mystery of Transformational Leadership Effects" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 12: 4534. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124534

APA StyleLu, Q., Liu, Y., & Huang, X. (2020). Follower Dependence, Independence, or Interdependence: A Multi-Foci Framework to Unpack the Mystery of Transformational Leadership Effects. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(12), 4534. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124534