Implementation of the National Action Plan Health Literacy in Germany—Lessons Learned

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Origin and Structure of the National Action Plan Health Literacy in Germany

2.2. Framing the Implementation of the National Action Plan Health Literacy in Germany

2.3. Theoretical Considerations of the Implementation Strategy

3. Results

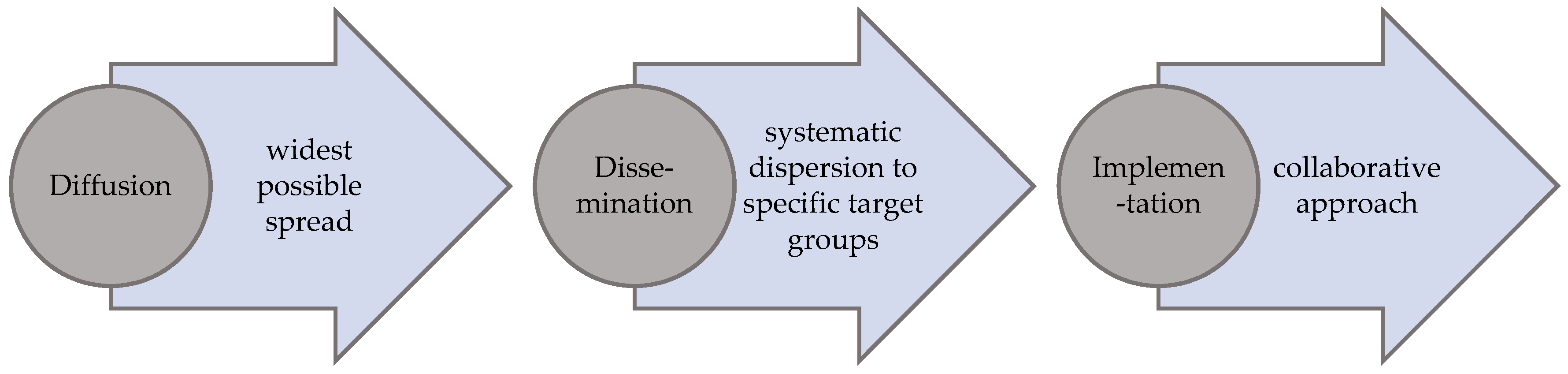

3.1. First Step in the Process of Realization: Diffusion

3.2. Second Step in the Process of Realization: Dissemination

3.3. Third Step in the Process of Realization: Collaborative Implementation

3.3.1. Workshops

- Health literacy in the education and training system;

- Importance of the media for strengthening health literacy (2 workshops);

- User-friendly and health literate health care system;

- Integrating health literacy into the care of people with chronic illness;

- Strengthening health literacy in a diverse society: Focus on migration;

- Systematic research on health literacy.

- Short introduction to the topic, to available empirical findings and the appropriate recommendation by one of the National Action Plan editors.

- Statements by the participants on the topic of the workshop; presentation of their respective perspectives; and, from their point of view, priority aspects of implementation, followed by an initial summarizing discussion.

- Division into working groups, detailed discussion of specific sub-topics, and development of specific implementation proposals.

- Presentation of the results for implementation and detailed summary discussion with initial focus on the strategy paper.

- Summarization of the feedback round.

- Trained junior scientists documented the workshops extensively. This documentation served as the fundament for developing and preparing the strategy papers (see below), as well as data material for the evaluation of the workshop.

3.3.2. Excursus: An Example Workshop

- To envisage the health care system from the perspective of those living with chronic illness.

- Anchor health literacy into the everyday life of people with chronic conditions and facilitate participation.

- Offer the right information at the right time: support people with chronic conditions through a systematic health management during the entire illness trajectory.

- Understand the acquisition of information and knowledge as a learning process.

- Promote advocacy support.

3.3.3. Cooperation with the Alliance for Health Literacy

4. Discussion

- It is necessary not only to invest into the development of action plans but also to plan the implementation followed by a systematic and scientifically sound and carefully planned dynamic implementation process.

- Diffusion and dissemination are imperative to making new innovative concepts and programs known.

- Innovations are always met with reservations. Therefore, it is important to anticipate obstacles and resistance and also to find solutions.

- Collaborative workshops with stakeholders have proven to be very important.

- Implementation requires sufficient financial and time resources as well as a specific qualification.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sørensen, K.; van den Broucke, S.; Fullam, J.; Doyle, G.; Pelikan, J.; Slonska, Z.; Brand, H. Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kickbusch, I.; Maag, D.; Saan, H. Enabling Healthy Choices in Modern Health Societies; European Health Forum: Badgastein, Austria, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen, K.; Pelikan, J.M.; Röthlin, F.; Ganahl, K.; Slonska, Z.; Doyle, G.; Fullam, J.; Kondilis, B.; Agrafiotis, D.; Uiters, E.; et al. Health literacy in Europe: Comparative results of the European health literacy survey (HLS-EU). Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 25, 1053–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkman, N.D.; Sheridan, S.L.; Donahue, K.E.; Halpern, D.J.; Viera, A.; Crotty, K.; Holland, A.; Brasure, M.; Lohr, K.N.; Harden, E.; et al. Health literacy interventions and outcomes: An updated systematic review. Evid. Rep. Technol. Assess. (Full Rep.) 2011, 199, 1–941. [Google Scholar]

- IUHPE Global Working Group on Health Literacy. IUHPE Position Statement on Health Literacy: A practical vision for a health literate world. Glob Health Promot. 2018, 25, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutbeam, D. Health literacy as a public health goal: A challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot. Int. 2000, 15, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, R.; Ratzan, S.C. Health literacy: A second decade of distinction for Americans. J. Health Commun. 2010, 15 (Suppl. 2), 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowlands, G.; Russell, S.; O’Donnell, A.; Kaner, E.; Trezona, A.; Rademakers, J.; Nutbeam, D. Health Evidence Network Synthesis Report 57. What is the Evidence on Existing Policies and Linked Activities and their Effectiveness for Improving Health Literacy at National, Regional and Organizational Levels in the WHO European Region? WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Trezona, A.; Rowlands, G.; Nutbeam, D. Progress in Implementing National Policies and Strategies for Health Literacy-What Have We Learned so Far? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondia, K.; Adriaenssens, J.; Van Den Broucke, S.; Kohn, L. Health Literacy: What Lessons Can Be Learned from the Experiences of Other Countries? Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre (KCE): Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2010.

- Scottish Government. Making it Easy. A Health Literacy Action Plan for Scotland; Scottish Government: Edinburgh, Scotland, 2014.

- Telo de Arriaga, M.; dos Santos, B.; Silva, A.; Mata, F.; Chaves, N.; Freitas, G. Plano de Ação para a Literacia em Saúde. Health Literacy Action Plan Portugal; Direção-Geral da Saúde: Lisbon, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer, D.; Hurrelmann, K.; Bauer, U.; Kolpatzik, K.; Gille, S.; Vogt, D. Der Nationale Aktionsplan Gesundheitskompetenz—Notwendigkeit, Ziel und Inhalt. Gesundheitswesen 2019, 81, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, D.; Vogt, D.; Berens, E.-M.; Hurrelmann, K. Gesundheitskompetenz der Bevölkerung in Deutschland: Ergebnisbericht; Universität Bielefeld: Bielefeld, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zok, K. Unterschiede bei der Gesundheitskompetenz. Ergebnisse einer bundesweiten Repräsentativ-Umfrage unter gesetzlich Versicherten. WIdO Monit. 2014, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, S.; Hoebel, J. Gesundheitskompetenz von Erwachsenen in Deutschland. Ergebnisse der Studie „Gesundheit in Deutschland aktuell“ (GEDA). Bundesgesundheitsblatt-Gesundh. Gesundh. 2015, 58, 942–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, D.; Hurrelmann, K.; Bauer, U.; Kolpatzik, K. National Action Plan Health Literacy. Promoting Health Literacy in Germany; KomPart: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, P.A.; Reich, M.R. Political Analysis for Health Policy Implementation. Health Syst. Reform 2019, 5, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsen, P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Sørensen, E.; Torfing, J. Improving policy implementation through collaborative policymaking. Policy Polit. 2017, 45, 467–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsky, M. Street-level Bureaucracy; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, M.; Moffit, A.; Kihn, P. Deliverology 101: A Field Guide for Educational Leaders; Corwin Press: California, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Howlett, M.A.; McConnell, A.; Perl, A. Steams and stages: Reconciling Kingdon and policy process theory. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 2015, 54, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapf, W. Modernisierung, Wohlfahrtsentwicklung und Transformation: Soziologische Aufsätze 1987 bis 1994; Editor Sigma: Berlin, Germany, 1994; pp. 11–40. [Google Scholar]

- Nationaler Aktionsplan Gesundheitskompetenz. Available online: https://www.nap-gesundheitskompetenz.de/ (accessed on 17 June 2020).

- Schaeffer, D.; Schmidt-Kaehler, S.; Dierks, M.-L.; Ewers, M.; Vogt, D. Strategiepapier #2 zu den Empfehlungen des Nationalen Aktionsplans. Gesundheitskompetenz in Die Versorgung von Menschen mit Chronischer Erkrankung Integrieren; Nationaler Aktionsplan Gesundheitskompetenz: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesministerium für Gesundheit. Allianz für Gesundheitskompetenz. Gemeinsame Erklärung; Bundesministerium für Gesundheit: Berlin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Interview with Jens Spahn, Federal Minister of Health. Germany. Public Health Panor. 2019, 5, 163–165. [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer, D.; Bauer, U.; Hurrelmann, K. Strategiepapier #5 zu den Empfehlungen des Nationalen Aktionsplans. Gesundheitskompetenz Systematisch Erforschen; Nationaler Aktionsplan Gesundheitskompetenz: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Weishaar, H.; Hurrelmann, K.; Okan, O.; Horn, A.; Schaeffer, D. Framing health literacy: A comparative analysis of national action plans. Health Policy 2019, 123, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaeffer, D. Probleme bei der Implementation neuer Versorgungsprogramme für Patienten mit HIV-Symptomen. Neue Prax. Z. Sozialarb. Sozialpädag. Sozialpolit. 1991, 21, 392–406. [Google Scholar]

| Date | Workshop Title | Number and Type of Participants | Outcome 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 25 June 2018 | Enabling the education and training system to promote health literacy early in life | 32 participants from politics, governmental institutions, national associations, public health, foundations, academia, practical projects | Strategy paper with 4 strategic propositions for implementation |

| 31 October 2018 | Integrating health literacy into the care of people with chronic illness | 29 participants from politics, leading health care and social organizations, patient and self-help organizations, academia | Strategy paper with 5 strategic propositions for implementation |

| 12 November 2018 | Facilitating the handling of health information in the media | 42 participants from politics, online platforms and portals, magazines, TV productions, broadcasting agencies, governmental institutions, foundations, academia, journalism | Strategy paper with 4 strategic propositions for implementation |

| 25 January 2019 | Integrating health literacy as standard at all levels of the healthcare system | 38 participants from politics, the Alliance for Health Literacy, health insurances, governmental institutions, national associations, academia, foundations | Strategy paper with 5 strategic propositions for implementation |

| 2–3 May 2019 | Systematic research on health literacy | 200 national and international participants on the international symposium “Health literacy: research–practice–politics” | Strategy paper with 4 strategic propositions for implementation |

| 20 September 2019 | Strengthening health literacy in a diverse society: Focus on migration | 28 participants from migrant- and self-help organizations, national associations, practical projects, academia, health care institutions | Strategy paper with 5 strategic propositions for implementation |

| 4 February 2020 | Importance of mass media for strengthening health literacy | Podium discussion with 8 journalists, 50 participants with expertise in health literacy | Conference report summarizing the results of the discussions |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schaeffer, D.; Gille, S.; Hurrelmann, K. Implementation of the National Action Plan Health Literacy in Germany—Lessons Learned. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4403. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124403

Schaeffer D, Gille S, Hurrelmann K. Implementation of the National Action Plan Health Literacy in Germany—Lessons Learned. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(12):4403. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124403

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchaeffer, Doris, Svea Gille, and Klaus Hurrelmann. 2020. "Implementation of the National Action Plan Health Literacy in Germany—Lessons Learned" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 12: 4403. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124403

APA StyleSchaeffer, D., Gille, S., & Hurrelmann, K. (2020). Implementation of the National Action Plan Health Literacy in Germany—Lessons Learned. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(12), 4403. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124403