Strategies for Attention to Diversity: Perceptions of Secondary School Teaching Staff

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Plans for Attention to Diversity

1.2. Degree of Compliance with Strategies for Attention to Diversity

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instrument

2.3. Procedure

3. Results

3.1. School Environment

3.2. Definition of the Improvement Strategy

3.3. Planning of the Improvement Strategy

3.4. Curricular Design

3.5. Human Resources for Attending to Diversity

3.6. Equipment and Resources

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Giné, C. Inclusión y sistema educativo. In Proceedings of the III Congreso La Atención a la Diversidad en el Sistema Educativo. Universidad de Salamanca. Instituto Universitario de Integración en la Comunidad (INICO), Salamanca, Spain, 6–9 September 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, J.F. La respuesta educativa al alumnado con altas capacidades desde el enfoque curricular: Del plan de atención a la diversidad a las adaptaciones curriculares individuales. Faisca Rev. Altas Capacid. 2008, 13, 40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, S.K. What is diversity? An inquiry into preservice teacher beliefs. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2010, 47, 292–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.D.; Bacdayan, P. Organizational routines are stored as procedural memory evidence from laboratory study. Organ. Sci. 1994, 4, 554–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponte, J.P. Concepções dos Professores de Matemática e Processos de Formação. In Educação Matemática: Temas de Investigação; Ponte, J.P., Ed.; Instituto de Inovação Educacional: Lisboa, Portugal, 1992; pp. 185–239. [Google Scholar]

- Ponte, J.P. Mathematics teachers’ professional knowledge. In PME XVIII: Proceedings of the Eighteenth International Conference for the Psychology of Mathematics Education, Lisbon, Portugal, 29 July–3 August 1994; Ponte, J.P., Matos, J.F., Eds.; Program Committee of the 18th PME Conference: Lisboa, Portugal, 1994; Volume I, pp. 195–210. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras, L.C. Resolución de Problemas: Un Análisis Exploratorio de las Concepciones de los Profesores Acerca de su Papel en el Aula. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Huelva, Huelva, Spain, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Araque, N.; Barrio, J.L. Atención a la Diversidad y Desarrollo de Procesos Educativos Inclusivos. Prism. Soc. Rev. Investig. Soc. 2010, 4, 13–50. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, B. Luces y sombras de las medidas de atención a la diversidad en el camino de la inclusión educativa. Rev. Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2011, 70, 165–184. [Google Scholar]

- Cejudo, J.; Díaz, M.V.; Losada, L.; Pérez-González, J.C. Necesidades de formación de maestros de infantil y primaria en atención a la diversidad. Bordón Rev. Pedagog. 2016, 68, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, J.M.; Espiñeira, E.M. Plan de Mejoras fruto de la evaluación de la calidad de la atención a la diversidad en un centro educativo. Rev. Investig. Educ. 2010, 28, 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ballard, K. Children and disability: Special or included. Waikato J. Educ. 2016, 10, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Azorín, C.M.; Arnaiz, P.; Maquilón, J.J. Revisión de instrumentos sobre atención a la diversidad para una educación inclusiva de calidad. Rev. Mex. Investig. Educ. 2017, 22, 1021–1045. [Google Scholar]

- Azorín, C.M. Análisis de instrumentos sobre educación inclusiva y atención a la diversidad. Rev. Complut. Educ. 2017, 28, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craft, M. Education for Diversity. In Education and Cultural Pluralism; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 5–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman, J.M.; Hallahan, D.P.; Pullen, P.C.; Badar, J. Special Education: What It Is and Why We Need It; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, I.; Woodcock, S. Inclusive education policies: Discourses of difference, diversity and deficit. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2015, 19, 141–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moliner, O.; Sales, A.; Ferrández, R.; Traver, J. Inclusive cultures, policies and practices in Spanish compulsory secondary education schools: Teachers’ perceptions in ordinary and specific teaching contexts. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2011, 15, 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, A.M. Modelos de Atención a la Diversidad en Educación Secundaria Obligatoria: Análisis Comparativo de los Planes de Atención a la Diversidad de las Comunidades Autónomas de Andalucía y de la Región de Murcia. Rev. Educ. Inclusiva 2017, 6, 41–64. [Google Scholar]

- Arnaiz, P.; Guirao, J.M. La autoevaluación de centros en España para la atención a la diversidad desde una perspectiva inclusiva: ACADI. Rev. Electron. Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2015, 18, 45–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornby, G. Inclusive special education: Development of a new theory for the education of children with special educational needs and disabilities. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 2015, 42, 234–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.; Dyson, A.; Millward, A. Towards Inclusive Schools? Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez, J.; López, A.; Vazquez, E. Atención a la diversidad en la educación secundaria obligatoria: Análisis desde la inspección educativa. Aula Abierta 2016, 44, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiner, E.; Cardona, M.C. Inclusive education in Spain: How do skills, resources, and supports affect regular education teachers’ perceptions of inclusion? Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2013, 17, 526–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, B. Calidad, equidad e indicadores en el sistema educativo español. Pulso. Rev. Educ. 2018, 29, 43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ruben, B.D. Quality in Higher Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer, F.T. Equality and quality in education. A comparative study of 19 countries. Soc. Sci. Res. 2015, 51, 350–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escarbajal, A.; Mirete, A.B.; Maquilón, J.J.; Izquierdo, T.; López, J.I.; Orcajada, N.; Sánchez, M. La atención a la diversidad: La educación inclusiva. Rev. Electron. Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2012, 15, 135–144. [Google Scholar]

- Gento, S. Propuesta para una acción educativa de calidad en el tratamiento de la diversidad. Rev. Complut. Educ. 2006, 17, 13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kerlinger, F.M. Entrevista y programa de entrevista. Investig. Comport México Interamericana 1987, 337–345. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, G.; Gil, J.; García, E. Metodología de la Investigación Cualitativa; Aljibe: Malaga, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Arnáiz, P.; Azorín, C.M. Autoevaluación docente para la mejora de los procesos educativos en escuelas que caminan hacia la inclusión. Rev. Colomb. Educ. 2014, 67, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondra, A.Z.; Hinings, C.R. Organizational diversity and change in institutional theory. Organ. Stud. 1998, 19, 743–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coll, C.; Barberà, E.; Onrubia, J. La atención a la diversidad en las prácticas de evaluación. Infanc. Aprendiz. 2000, 23, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, J.; Vázquez, E. Atención a la diversidad: Análisis de la formación permanente del profesorado en Galicia. Rev. Educ. Inclusiva 2017, 8, 139–152. [Google Scholar]

- González, F.; Martín, E.; Flores, N.; Jenaro, C.; Poy, R.; Gómez, M. Teaching, learning and inclusive education: The challenge of teachers’ training for inclusion. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 93, 783–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

| Typology of the Centre | Total Teaching Staff of the Centre | Participating Teaching Staff | Participation Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quality Centre A | 41 | 37 | 94.24% |

| Quality Centre B | 48 | 45 | 93.75% |

| Quality Centre C | 46 | 30 | 65.22% |

| Total | 135 | 112 |

| Alpha | |

|---|---|

| Overall questionnaire | 0.9569 |

| School environment | 0.8641 |

| Definition of improvement strategy | 0.8893 |

| Planning of improvement strategy | 0.8713 |

| Curricular design | 0.8947 |

| Human resources addressing diversity | 0.8050 |

| Equipment and resources | 0.8938 |

| Degree of Consensus in the Objectives of the Centre for Attending to Diversity | Available Resources | Physical and Environmental Infrastructures to Meet the Diversity of the Centre | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Not important | 1.0% | 1.0% | 1.0% |

| A little important | 1.9% | 3.9% | 2.9% |

| Important | 18.4% | 24.3% | 22.3% |

| Quite important | 45.6% | 23.3% | 34.0% |

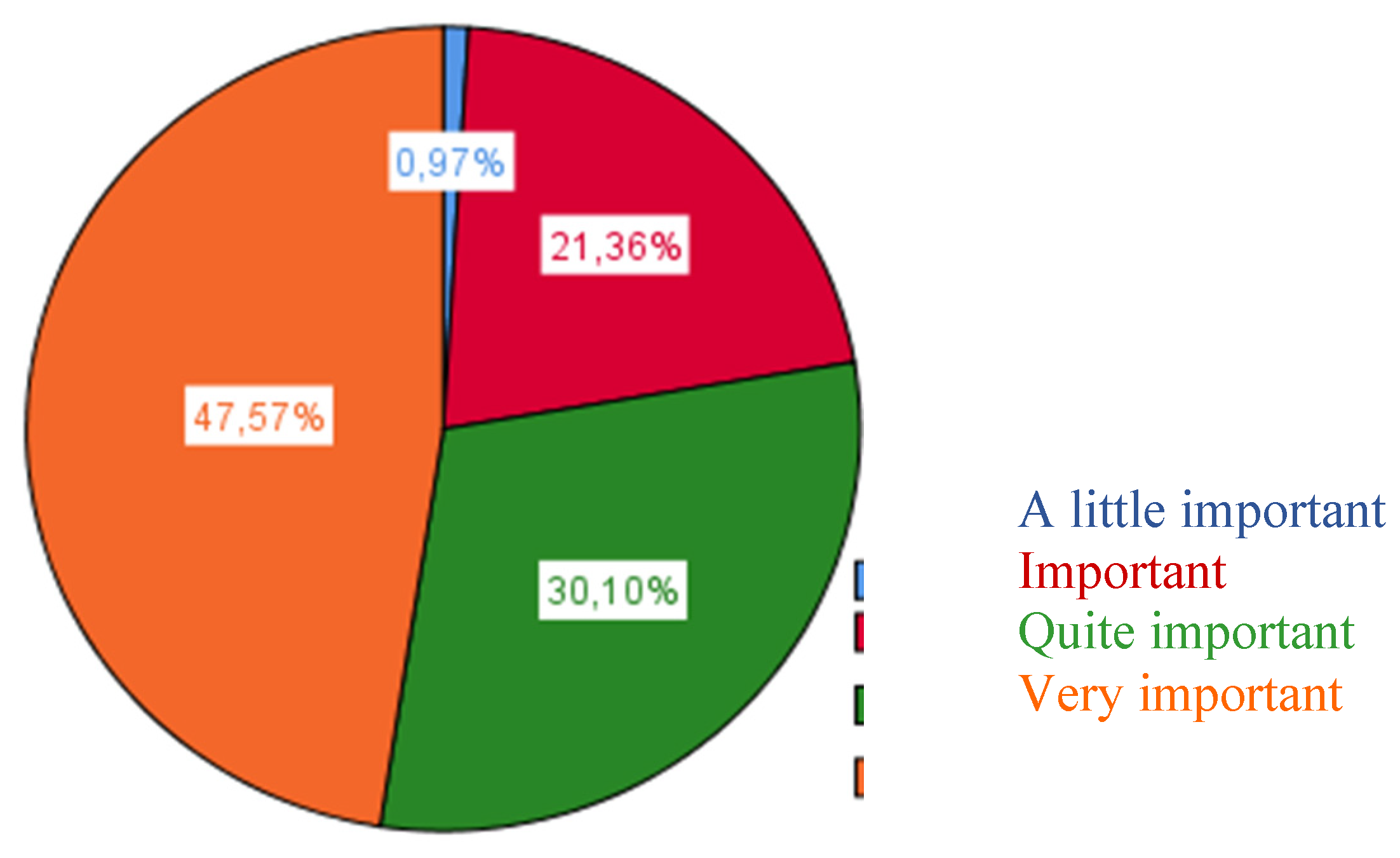

| Very important | 33.0% | 47.6% | 39.8% |

| Total | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

| Item | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Modification of the organisation of teaching following the inclusion plan. | 3.93 | 0.867 |

| Appropriateness of the curricular competence of each student with Special Educational Needs (NEE) to the predetermined objectives and goals. | 4.09 | 0.931 |

| Appropriateness of the teacher-student ratio to the characteristics of the students with NEE in each classroom and school. | 4.37 | 0.889 |

| Coordination and joint working of the entire department | 4.44 | 0.730 |

| Appropriateness of the adaptations of Education Plan (PEC) and Curriculum Project (PCC) in order to give effective responses to the objectives of the school relating to attention to diversity. | 4.15 | 0.722 |

| Design and use of evaluations based on the real curriculum received by students in the classrooms and school. | 4.17 | 0.789 |

| Appropriateness and Novelty of the Special Equipment and Resources for Addressing Diversity in Each Centre | Quantity and Quality of Specific Equipment Related with NEE | Adaptability, Functionality and Safety of All of the Centre’s Facilities, Especially in the Classrooms | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Not at all important | 1.0% | 0% | 0% |

| A little important | 2.9% | 2.9% | 1.9% |

| Important | 17.5% | 16.5% | 22.3% |

| Quite important | 44.7% | 44.7% | 36.9% |

| Very important | 34.0% | 35.9% | 38.8% |

| Total | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

| Items | Sex | Mean | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics of all of the students at the educational centre. | Male | 3.77 | 0.001 |

| Female | 4.39 | ||

| Potential for professional integration of students with special educational needs. | Male | 3.34 | 0.000 |

| Female | 4.05 | ||

| Collaboration through cooperative programs with other educational and social institutions. | Male | 3.43 | 0.012 |

| Female | 3.88 | ||

| The organisational structure in place to respond to the objectives of the improvement strategy. | Male | 3.58 | 0.001 |

| Female | 4.14 | ||

| Limitations to achieving agreed objectives. | Male | 3.92 | 0.023 |

| Female | 3.58 | ||

| An approach for measurement must be developed. | Male | 4.28 | 0.000 |

| Female | 3.81 | ||

| Appropriateness of the teacher–student ratio to the characteristics of students with NEE in each classroom and educational centre. | Male | 4.32 | 0.005 |

| Female | 3.83 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Goig Martínez, R.; Martínez Sánchez, I.; González González, D.; García Llamas, J.L. Strategies for Attention to Diversity: Perceptions of Secondary School Teaching Staff. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3840. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17113840

Goig Martínez R, Martínez Sánchez I, González González D, García Llamas JL. Strategies for Attention to Diversity: Perceptions of Secondary School Teaching Staff. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(11):3840. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17113840

Chicago/Turabian StyleGoig Martínez, Rosa, Isabel Martínez Sánchez, Daniel González González, and José Luis García Llamas. 2020. "Strategies for Attention to Diversity: Perceptions of Secondary School Teaching Staff" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 11: 3840. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17113840

APA StyleGoig Martínez, R., Martínez Sánchez, I., González González, D., & García Llamas, J. L. (2020). Strategies for Attention to Diversity: Perceptions of Secondary School Teaching Staff. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(11), 3840. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17113840