Perception of Gender-Based Violence and Sexual Harassment in University Students: Analysis of the Information Sources and Risk within a Relationship

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Objectives

- Analyzing the relationships between knowledge about violence situations, sources of information and risk situations in couple relationships among university students.

- Creating profiles among students about the knowledge of violent situations to detect differences between the sources of information used and their perception of risky situations.

- Checking the relation between the knowledge of risky situations of gender-based violence and the place of residence (rural vs. urban) and the sex of the participants.

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

3.2. Instrument

3.3. Procedure and Analysis

3.4. Analysis of Data

4. Results

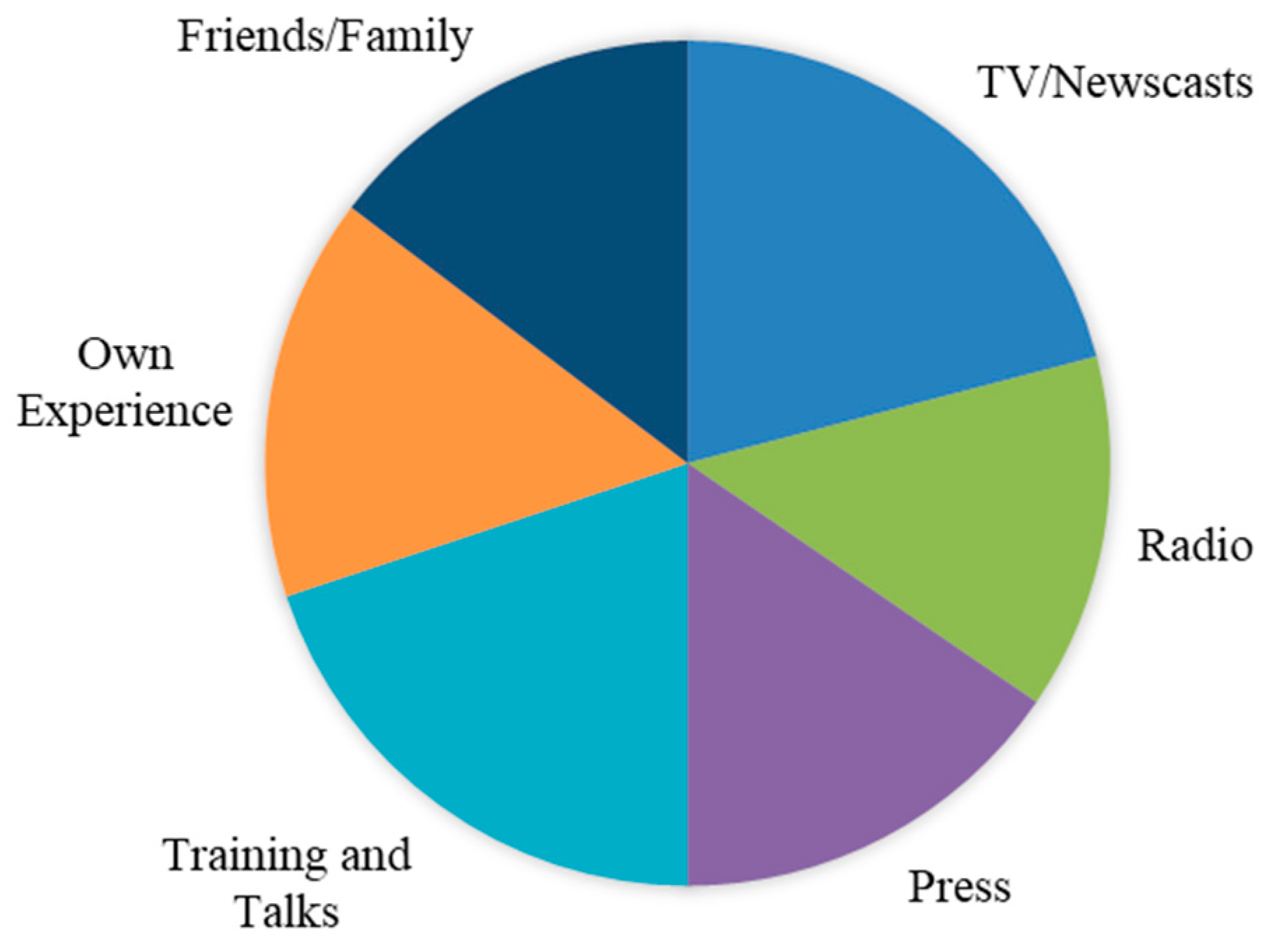

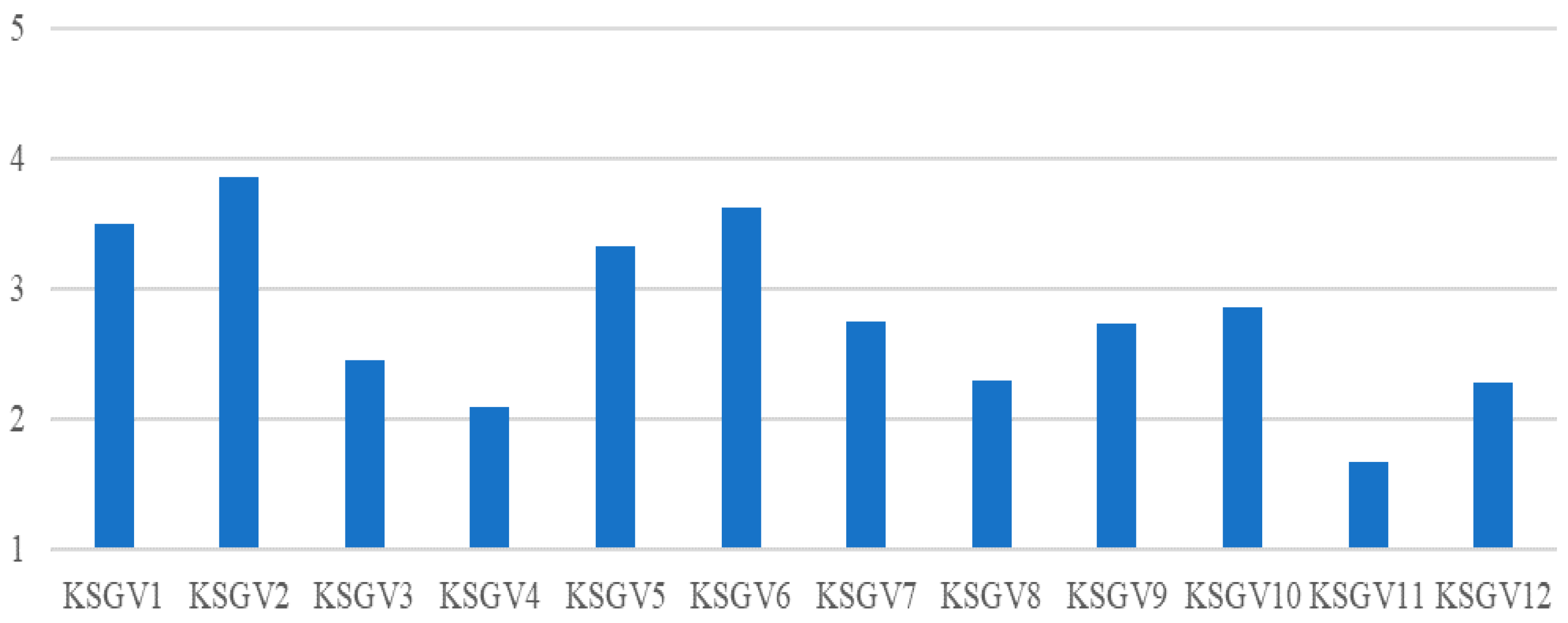

4.1. Descriptive Results on Knowledge of Situations of Violence, Sources of Information, and Situations of Risk in Relationships

4.2. Correlations between Variables Referring to Knowledge about Situations of Violence, Sources of Information, and Situations of Risk in a Relationship

4.3. Profile of Student Knowledge on Situations of Violence and Differences as a Function of Sources of Information and Situations of Risk

4.4. Results for Knowledge of Situations of Violence in the Rural and Urban Environments

4.5. Results for Knowledge of Situations of Violence, Sources of Information, and Situations of Risk According to Gender

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Limitations and Future Lines of Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Valls, R.; Oliver, E.; Sánchez, M.; Ruíz, L.; Melgar, P. Gender violence also in universities? Research in this regard. Rev. Investig. Educ. 2007, 25, 219–231. [Google Scholar]

- Igareda, N.; Bodelón, E. Sexual violence and sexual harassment in the Spanish university. Riv. Criminol. Vittimol. Sicur. 2013, 7, 65–79. [Google Scholar]

- Amorós, C.; De Miguel, A. Feminist Theory. From Illustration to Globalization; Minerva: Madrid, Spain, 2005; ISBN 84-88123-53-1. [Google Scholar]

- De Miguel, A. Feminist perspectives in 21st century Spain (between the floor and the glass ceiling) Labrys Études Féministes. 2006, Volume 10. Available online: www.labrys.net.br/labrys10/sumarioespanha.htm (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Millett, K. Sexual Politics; Cátedra: Madrid, Spain, 2017; ISBN 9788437637372. [Google Scholar]

- Korac, M. Feminists against Sexual Violence in War: The Question of Perpetrators and Victims Revisited. Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorós, C. Women and Imaginary of Globalization; Homo Sapiens Ediciones: Sarmiento, Argentina, 2008; ISBN 978-84-17408-33-6. [Google Scholar]

- Di Napoli, I.; Procentese, F.; Carnevale, E.; Esposito, C.; Arcidiacono, C. Ending Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) and Locating Men at Stake: An Ecological Approach. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer, V.A.; Bosch, E.; Navarro Guzmán, C. Gender violence in university education: Analysis of predictive factors. An. Psicol. 2011, 27, 435–446. Available online: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=16720051021 (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Kaufman, M.R.; Williams, A.M.; Grilo, G.; Marea, C.X.; Fentaye, F.W.; Gebretsadik, L.A.; Yedenekal, S.A. “We are responsible for the violence, and prevention is up to us”: A qualitative study of perceived risk factors for gender-based violence among Ethiopian university students. BMC Women Health 2019, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puigvert, L. Breaking the silence: The Struggle against Gender Violence in Universities. Int. J. Crit. Pedagog. 2008, 1, 1–10. Available online: http://freireproject.org/wp-content/journals/TIJCP/Vol1No1/50-40-1-PB.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Bosch, E.; Ferrer, V.A.; Alzamora, A. The Patriarchal Maze; Antrophos: Barcelona, Spain, 2006; ISBN 84-7658-798-8. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Acobo, Y.R.; Choqque-Soto, S. Perception of violence and sexism in university students. Rev. Entorno 2018, 66, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igareda, N. Guia per a la Prevenció I Atenció en Cas de Violència de Gènere a la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain. 2011. Available online: https://ddd.uab.cat/record/90114 (accessed on 23 May 2020).

- Kelly, L. What’s in a Name? Defining Child Sexual Abuse. Fem. Rev. 1988, 28, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. Convention Europe’s Council for Prevention and Fight against Violence against Women and Domestic Violence. 2011. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/1680462543 (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Cubells, J.; Calsamiglia, A. Romantic love’s repertoire and the conditions of possibility of violence against women. Psychology 2015, 14, 1681–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Miguel, A. Building a feminist framework of interpretation: Gender violence. Soc. Work Noteb. 2005, 18, 231–248. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P.H.; White, J.W.; Holland, L. A Longitudinal Perspective on Dating Violence among Adolescents and College-Age Women. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dueñas, D.; Pontón, P.; Belzunegui, A.; Pastor, I. Discriminatory expressions, youth and social networks: The influence of gender. Comunicar 2016, 46, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, V.A.; Bosch, E. From romantic love to gender violence. For an emotional coeducation on the educational guide. Profr. Rev. Curric. Form. Profr. 2013, 17, 105–121. Available online: https://www.ugr.es/~recfpro/rev171ART7.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Larena Fernández, R.; Molina Roldán, S. Gender violence in universities: Research and measures to prevent it. Glob. Soc. Work 2010, 1, 202–219. [Google Scholar]

- General Assembly Resolution 48/104 20nd of December, 1993. Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women. Available online: https://www.acnur.org/fileadmin/Documentos/BDL/2002/1286.pdf?file=fileadmin/Documentos/BDL/2002/1286 (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Luchsinger, G. A Short History of the Commission on the Status of Women. United States of America: Un Women. 2019. Available online: http://www.unwomen.org/-/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/publications/2019/a-short-history-of-the-csw-en.pdf?la=en&vs=1153 (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. Violence against Women: An EU-Wide Survey. 2014. Available online: http://fra.europa.eu/en/publication/2014/violence-against-women-eu-wide-survey-main-results-report (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- RED2RED; Pernas Riaño, B. The State of the Matter in the Study of Gender Violence; Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality: Madrid, Spain, 2013; Available online: https://www.aragon.es/documents/20127/674325/Estado_de__la__cuestion.pdf/67fd2ab4-a1f2-5e9b-f303-739d7de155f1 (accessed on 23 May 2020).

- Machado, A.L.; Marques, M.J. Rural women and violence: Readings of a reality that approaches fiction. Ambiente Soc. 2018, 21, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Santoro, C.; Martínez-Ferrer, B.; Monreal Gimeno, C.; Musitu, G. New Directions for Preventing Dating Violence in Adolescence: The Study of Gender Models. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlshamare, M. Report on the Current Situation in the Fight against Violence Women and Future Actions (2004/2220(INI). European Parliament Report A6-0404/2005. 2005. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-//EP//NONSGML+TA+P6-TA-2006-0038+0+DOC+PDF+V0//ES (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Flecha, A.; Puigvert, L.; Redondo, G. Preventive socialization of gender violence. Feminismo/s 2005, 6, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernando, A.; García, A.; Montilla, M. Exploración de las actitudes y conductas de jóvenes universitarios antes la violencia en las relaciones de pareja. Rev. Complut. Educ. 2012, 23, 427–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondurant, B. University Women’s Acknowledgment of Rape. Violence Women 2001, 7, 294–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, A.; Winslett, A.; Gohm, C. Research Note: An examination of sexual violence against college women. Violence Women 2006, 12, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Presidency of the European Union, Spain. Study on the Measures Taken, by the Member States of the European Union, to Fight Violence against Women; Women’s Institute: Madrid, Spain, 2002; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279176717_Estudio_sobre_las_medidas_adoptadas_por_los_Estados_Miembros_de_la_Union_Europea_para_luchar_contra_la_violencia_hacia_las_mujeres (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Presidency of the European Union, Spain. Good Practice Guide to Mitigate the Effects of Violence against Women and Achieve its Eradication; Women’s Institute: Madrid, Spain, 2002; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279750097_Etude_sur_les_mesures_adoptees_par_les_Etats_Membres_de_l_Union_Europeenne_pour_la_lutte_contre_la_violence_a_legard_des_femmes (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Maquibar, A.; Estalella, I.; Vives-Cases, C.; Hurtig, A.K.; Goicolea, I. Analysing training in gender-based violence for undergraduate nursing students in Spain: A mixed-methods study. Nurse Educ. Today 2019, 77, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Airton, L.; Koecher, A. How to hit a moving target: 35 years of gender and sexual diversity in teacher education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2019, 80, 190–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo Nuñez, J.; Derluyn, I.; Valcke, M. Student teachers’ cognitions to integrate comprehensive sexuality education into their future teaching practices in Ecuador. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2019, 79, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharoni, S.; Klocke, B. Faculty confronting gender-based violence on campus: Opportunities and challenges. Violence Women 2019, 25, 1352–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinkinson, M. ‘Sexuality isn’t just about sex’: Pre-service teachers’ shifting constructs of sexuality education. Sex Educ. 2009, 9, 421–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banyard, V.L.; Plante, E.G.; Cohn, E.S.; Moorhead, C.; Ward, S.; Walsh, W. Revisting unwanted sexual experiences on campus. A 12-years follow-up. Violence Women 2005, 11, 426–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo, H.C.; Campo Arias, A. Approach to the use of Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Rev. Colomb. Psiquiatr. 2005, 34, 572–580. Available online: http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/806/80634409.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for Behavioral Sciences, revised ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977; ISBN 0-8058-0283-5. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, J.; Wolper, A. Women’s Rights, Human Rights: International Feminist Perspectives; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 0-41590994-5. [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez Laba, V.; Palumbo, M. Causes and effects of discrimination and gender-based violence in universities. Descentrada 2019, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Instrument | Items | |

|---|---|---|

| S-SRR (α = 0.757) | SRR1 | Prior to marriage |

| SRR2 | On trying to break up with the partner | |

| SRR3 | During marriage | |

| SRR4 | On having children | |

| SRR5 | During the process of divorce or separation | |

| SRR6 | After divorce or separation | |

| S-KSGV (α = 0.909) | KSGV1 | Constant control (of activities undertaken, of who one is with...) |

| KSGV2 | Jealousy (possessive feelings) | |

| KSGV3 | Threatening or intimidating phone messages or emails | |

| KSGV4 | Physical attack | |

| KSGV5 | Psychological attack | |

| KSGV6 | Sexist remarks | |

| KSGV7 | Pressure to engage in an emotional and/or sexual relationship | |

| KSGV8 | Kissing and/or touching without consent | |

| KSGV9 | Discomfort or fear due to feeling harassed or intimidated | |

| KSGV10 | Obscene remarks, rumors or attacks on sex life | |

| KSGV11 | Preferential treatment or academic favors in exchange for sexual favors | |

| KSGV12 | Demeaning use of Internet images, even as a “joke” | |

| TV | RD | PR | TC | OE | F/FE | S-SRR | S-KSGV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TV | 1 | |||||||

| RD | 0.361 ** | 1 | ||||||

| PR | 0.305 ** | 0.421 ** | 1 | |||||

| TC | −0.012 | −0.036 | 0.180 ** | 1 | ||||

| OE | −0.162 ** | 0.141 * | −0.038 | 0.090 | 1 | |||

| F/FE | −0.091 | −0.018 | 0.089 | 0.144 * | 0.417 ** | 1 | ||

| S-SRR | 0.040 | −0.104 | 0.098 | 0.064 | 0.006 | 0.232 ** | 1 | |

| S-KSGV | −0.051 | 0.057 | 0.171 ** | 0.150 * | 0.281 ** | 0.460 ** | 0.326 ** | 1 |

| Sources of Information | Profile | n | M | SD | t | p | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TV | Lower | 97 | 3.40 | 1.067 | −0.362 | 0.717 | 0.05 |

| Higher | 169 | 3.45 | 1.011 | ||||

| RD | Lower | 97 | 2.13 | 1.187 | −1.187 | 0.236 | 0.16 |

| Higher | 169 | 2.30 | 1.062 | ||||

| PR | Lower | 97 | 2.29 | 1.163 | −2.697 | 0.007 ** | 0.34 |

| Higher | 169 | 2.67 | 1.100 | ||||

| TC | Lower | 97 | 3.02 | 1.233 | −2.589 | 0.010 * | 0.33 |

| Higher | 169 | 3.41 | 1.141 | ||||

| OE | Lower | 97 | 2.10 | 1.271 | −3.858 | 0.000 ** | 0.50 |

| Higher | 169 | 2.79 | 1.456 | ||||

| F/FE | Lower | 97 | 1.77 | 1.221 | −6.064 | 0.000 ** | 0.75 |

| Higher | 169 | 2.77 | 1.402 |

| Situation of Risk | Profile | n | M | SD | t | p | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boyfriend/Girlfriend stage | Lower | 97 | 3.19 | 0.950 | −3.370 | 0.001 ** | 0.43 |

| Higher | 169 | 3.60 | 0.966 | ||||

| When wishing to break up | Lower | 97 | 4.20 | 0.886 | −2.104 | 0.036 * | 0.27 |

| Higher | 169 | 4.43 | 0.843 | ||||

| Within marriage | Lower | 97 | 3.42 | 1.329 | −1.575 | 0.116 | 0.21 |

| Higher | 169 | 3.69 | 1.306 | ||||

| With children | Lower | 97 | 3.47 | 0.936 | −2.793 | 0.006 ** | 0.36 |

| Higher | 169 | 3.81 | 0.951 | ||||

| During divorce/separation | Lower | 97 | 3.81 | 1.034 | −3.454 | 0.001 ** | 0.45 |

| Higher | 169 | 4.24 | 0.915 | ||||

| After divorce/separation | Lower | 97 | 3.91 | 1.091 | −1.271 | 0.205 | 0.16 |

| Higher | 169 | 4.08 | 1.024 |

| Measure | Gender | n | M | SD | t | p | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TV | Woman | 178 | 3.40 | 1.049 | −0.463 | 0.644 | 0.07 |

| Man | 90 | 3.47 | 1.019 | ||||

| RD | Woman | 178 | 2.26 | 1.110 | 0.560 | 0.576 | 0.07 |

| Man | 90 | 2.18 | 1.118 | ||||

| PR | Woman | 178 | 2.53 | 1.131 | 0.040 | 0.968 | 0.07 |

| Man | 90 | 2.52 | 1.154 | ||||

| TC | Woman | 178 | 3.28 | 1.159 | 0.380 | 0.704 | 0.05 |

| Man | 90 | 3.22 | 1.261 | ||||

| OE | Woman | 178 | 2.59 | 1.420 | 1.028 | 0.305 | 0.13 |

| Man | 90 | 2.40 | 1.444 | ||||

| F/FE | Woman | 178 | 2.40 | 1.363 | 0.082 | 0.935 | 0.01 |

| Man | 90 | 2.39 | 1.527 | ||||

| S-SRR | Woman | 178 | 3.94 | 0.619 | 2.447 | 0.016 * | 0.34 |

| Man | 90 | 3.71 | 0.804 | ||||

| S-KSGV | Woman | 177 | 2.87 | 0.951 | 1.984 | 0.048 * | 0.26 |

| Man | 90 | 2.62 | 0.978 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Osuna-Rodríguez, M.; Rodríguez-Osuna, L.M.; Dios, I.; Amor, M.I. Perception of Gender-Based Violence and Sexual Harassment in University Students: Analysis of the Information Sources and Risk within a Relationship. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17113754

Osuna-Rodríguez M, Rodríguez-Osuna LM, Dios I, Amor MI. Perception of Gender-Based Violence and Sexual Harassment in University Students: Analysis of the Information Sources and Risk within a Relationship. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(11):3754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17113754

Chicago/Turabian StyleOsuna-Rodríguez, Mercedes, Luis Manuel Rodríguez-Osuna, Irene Dios, and María Isabel Amor. 2020. "Perception of Gender-Based Violence and Sexual Harassment in University Students: Analysis of the Information Sources and Risk within a Relationship" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 11: 3754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17113754

APA StyleOsuna-Rodríguez, M., Rodríguez-Osuna, L. M., Dios, I., & Amor, M. I. (2020). Perception of Gender-Based Violence and Sexual Harassment in University Students: Analysis of the Information Sources and Risk within a Relationship. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(11), 3754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17113754