A Comparative Study on Adolescents’ Health Literacy in Europe: Findings from the HBSC Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

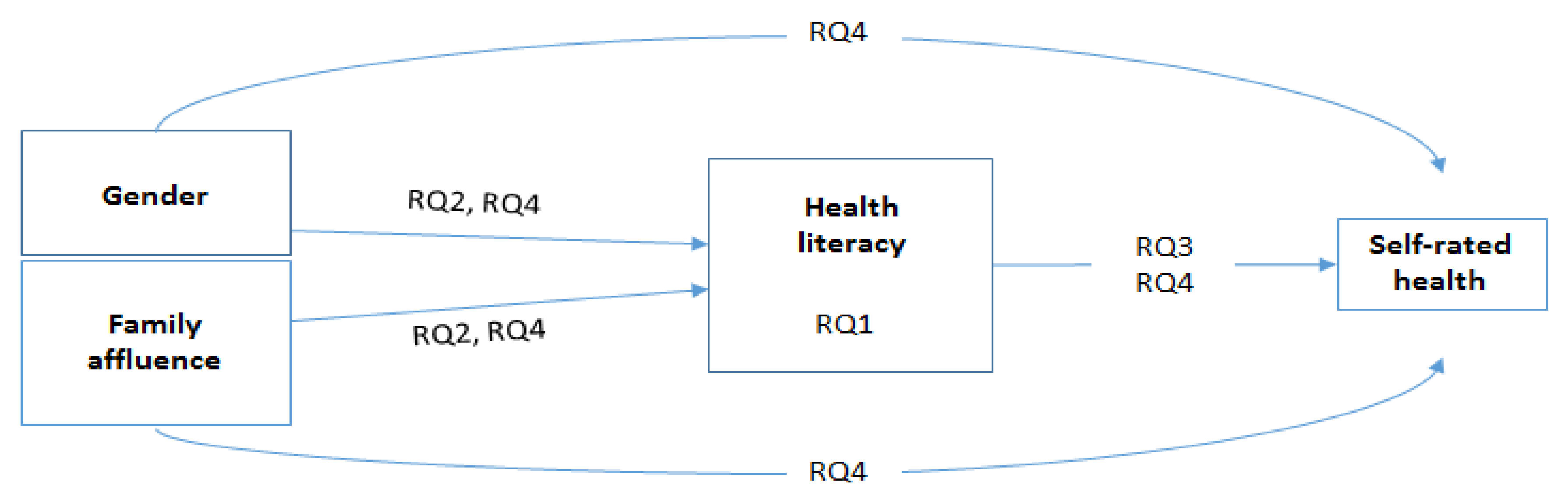

- Are there differences in adolescents’ health literacy in 10 European countries? (RQ1)

- Are (a) gender and (b) family affluence associated with health literacy in the 10 participating countries? (RQ2)

- Does health literacy explain self-rated health in the 10 participating countries? (RQ3)

- Does health literacy mediate the association between gender and self-rated health, or between family affluence and self-rated health, in the 10 participating countries? (RQ4)

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

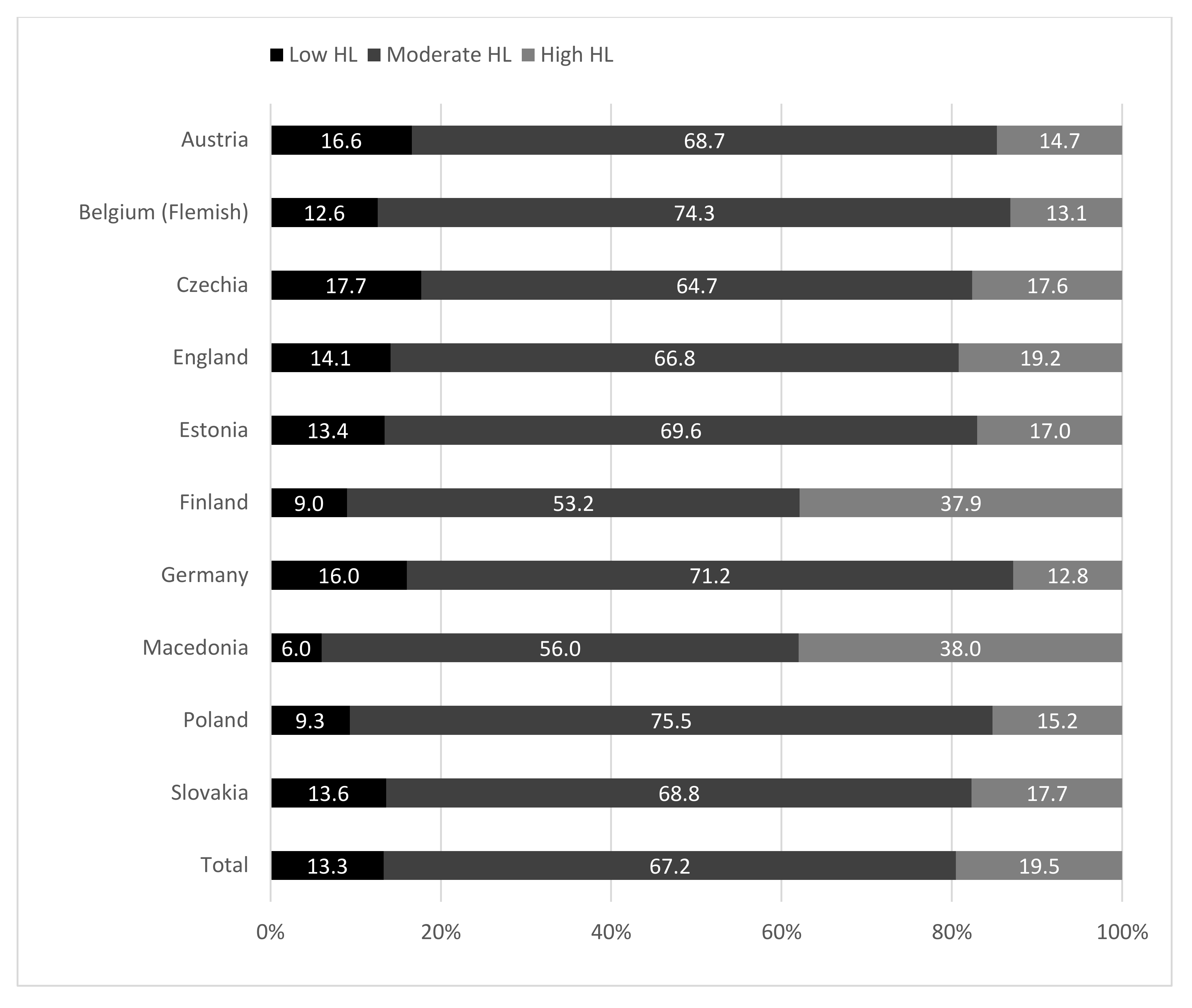

3.1. Differences in HL Level (RQ1)

3.2. Associations of Gender and Family Affluence with HL, and of HL with Self-Rated Health (RQ2–3)

3.3. HL as a Mediator between Gender, Family Affluence, and Self-Rated Health (RQ4)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Draft WHO European Roadmap for Implementation of Health Literacy Initiatives through the Life Course; World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Shanghai declaration on promoting health in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Health Promot. Int. 2017, 32, 7–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nutbeam, D. Health promotion glossary. Health Promot. Int. 1998, 13, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paakkari, L.; Torppa, M.; Paakkari, O.; Välimaa, R.; Ojala, R.; Tynjälä, J. Does health literacy explain the link between structural stratifiers and adolescent health? Eur. J. Public Health 2019, 29, 919–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viner, R.M.; Ozer, E.M.; Denny, S.; Marmot, M.; Resnick, M.; Fatusi, A.; Currie, C. Adolescence and the social determinants of health. Lancet 2012, 379, 1641–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paakkari, L.; George, S. Ethical underpinnings for the development of health literacy in schools: Ethical premises (‘why’), orientations (‘what’) and tone (‘how’). BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, K.; Pelikan, J.M.; Röthlin, F.; Ganahl, K.; Slonska, Z.; Doyle, G.; Fullam, J.; Kondilis, B.; Agrafiotis, D.; Uiters, E.; et al. Health literacy in Europe: Comparative results of the European health literacy survey (HLS-EU). Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 25, 1053–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hls-EU Consortium. Comparative Report of Health Literacy in Eight EU Member States. The European Health Literacy Survey HLS-EU. Second Revised and Extended Version, Date 22 July 2014. 2012. Available online: http://www.health-literacy.eu (accessed on 20 April 2019).

- Trezona, A.; Rowlands, G.; Nutbeam, D. Progress in implementing national policies and strategies for health literacy—What have we learned so far? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paakkari, O.; Torppa, M.; Villberg, J.; Kannas, L.; Paakkari, L. Subjective health literacy among school-aged children. Health Educ. 2018, 118, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fretian, A.; Bollweg, T.M.; Okan, O.; Pinheiro, P.; Bauer, U. Exploring Associated Factors of Subjective Health Literacy in School-Aged Children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukys, S.; Trinkuniene, L.; Tilindiene, I. Subjective Health Literacy among School-Aged Children: First Evidence from Lithuania. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Yu, X.; Davis, E.; Armstrong, R.; Riggs, E.; Naccarella, L. Adolescent Health Literacy in Beijing and Melbourne: A Cross-Cultural Comparison. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paakkari, O.; Torppa, M.; Boberova, Z.; Välimaa, R.; Maier, G.; Mazur, J.; Kannas, L.; Paakkari, L. The cross-national measurement invariance of the health literacy for school-aged children (HLSAC) instrument. Eur. J. Public. Health 2019, 29, 432–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavallo, F.; Dalmasso, P.; Ottova-Jordan, V.; Brooks, F.; Mazur, J.; Välimaa, R.; Gobina, I.; Gaspar de Matos, M.; Raven-Sieberer, U.; Positive Health Focus Group. Trends in self-rated health in European and North-American adolescents from 2002 to 2010 in 32 countries. Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 25, 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokol, R.; Ennett, S.; Gottfredson, G.; Halpern, C. Variability in self-rated health trajectories from adolescence to young adulthood by demographic factors. Prev. Med. 2017, 105, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fayers, P.M.; Sprangers, M.A. Understanding self-rated health. Lancet 2002, 359, 187–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauldry, S.; Shanahan, M.J.; Boardman, J.D.; Miech, R.A.; Macmillan, R. A life course model of self-rated health through adolescence and young adulthood. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 2012 75, 1311–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Heide, I.; Wang, J.; Droomers, M.; Spreeuwenberg, P.; Rademakers, J.; Uiters, E. The relationship between health, education, and health literacy: Results from the Dutch Adult Literacy and Life Skills Survey. J. Health Commun. 2013, 18, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inchley, J.; Currie, D.; Cosma, A.; Samdal, O. (Eds.) Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) Study Protocol: Background, Methodology and Mandatory Items for the 2017/18 Survey; CAHRU: St Andrews, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Torsheim, T.; Cavallo, F.; Levin, K.A.; Schnohr, C.; Mazur, J.; Niclasen, B.; Currie, C.; FAS Development Study Group. Psychometric validation of the revised family affluence scale: A latent variable approach. Child Indic. Res. 2016, 9, 771–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inchley, J.; Currie, D.; Young, T.; Samdal, O.; Torsheim, T.; Augustson, L.; Mathison, F.; Aleman-Diaz, A.; Molcho, M.; Weber, M.; et al. Growing up Unequal: Gender and Socioeconomic Differences in Young people’s Health and Well-being. Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) Study, International Report from the 2013/2014 Survey; Health Policy for Children and Adolescents, No. 7; WHO Regional Office Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Paakkari, O.; Torppa, M.; Kannas, L.; Paakkari, L. Subjective health literacy: Development of a brief instrument for school-aged children. Scand. J. Public Health 2016, 44, 751–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, G.A.; Camacho, T. Perceived health and mortality: A nine-year follow-up of the human population laboratory cohort. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1983, 117, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Davis, E.; Yu, X.; Naccarella, L.; Armstrong, R.; Abel, T.; Browne, G.; Shi, Y. Measuring functional, interactive and critical health literacy of Chinese secondary school students: Reliable, valid and feasible? Glob. Health Promot. 2018, 25, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stormacq, C.; Van den Broucke, S.; Wosinski, J. Does health literacy mediate the relationship between socioeconomic status and health disparities? Integrative review. Health Promot. Int. 2019, 34, e1–e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borzekowski, D.L. Considering children and health literacy: A theoretical approach. Pediatrics 2009, 124, S282–S288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolarcik, P.; Cepova, E.; Geckova, A.M.; Elsworth, G.R.; Batterham, R.W.; Osborne, R.H. Structural properties and psychometric improvements of the health literacy questionnaire in a Slovak population. Int. J. Public Health 2017, 62, 591–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kickbusch, I.; Pelikan, J.M.; Apfel, F.; Tsouros, A.D. Health Literacy. The Solid Facts; World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. PISA 2015 Results (Volume I): Excellence and Equity in Education; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rüegg, R.; Abel, T. The relationship between health literacy and health outcomes among male young adults: Exploring confounding effects using decomposition analysis. Int. J. Public Health 2019, 64, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bröder, J.; Okan, O.; Bollweg, T.M.; Bruland, D.; Pinheiro, P.; Bauer, U. Child and Youth Health Literacy: A Conceptual Analysis and Proposed Target-Group-Centred Definition. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowlands, G.; Russell, S.; O’Donnell, A.; Kaner, E.; Trezona, A.; Rademakers, J.; Nutbeam, D. What Is the Evidence on Existing Policies and Linked Activities and Their Effectiveness for Improving Health Literacy at National, Regional and Organizational Levels in the WHO European Region? Health Evidence Network (HEN) Synthesis Report 57; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Okan, O.; Sørensen, K.; Bauer, U. Health literacy policy-making regarding children and adolescents. Eur. J. Public Health 2019, 29, ckz185-554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okan, O.; Pinheiro, O.; Zamora, P.; Bauer, U. Health Literacy bei Kindern und Jugendlichen. Ein Überblick über den aktuellen Forschungsstand [Health literacy of children and adolescents. An overview and current state of research]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt 2015, 9, 930–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downey, D.B.; Von Hippel, P.T.; Broh, B.A. Are schools the great equalizer? Cognitive inequality during the summer months and the school year. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2004, 69, 613–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuya, Y.; Kondo, N.; Yamagata, Z.; Hashimoto, H. Health literacy, socioeconomic status and self-rated health in Japan. Health Promot. Int. 2015, 30, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSalvo, K.B.; Bloser, N.; Reynolds, K.; He, J.; Muntner, P. Mortality prediction with a single general self-rated health question: A meta-analysis. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2006, 21, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Country | N | Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 1190 | 29.88 5,6,8,9,10 | 5.32 | −0.53 | 1.52 |

| Belgium (Flemish) | 1374 | 30.33 6,8 | 4.73 | −0.58 | 1.24 |

| Czechia | 3154 | 30.06 6,8,9,10 | 5.72 | −0.51 | 0.90 |

| England | 710 | 30.57 6,8 | 5.57 | −0.57 | 0.99 |

| Estonia | 1506 | 30.54 1,6,8 | 4.98 | −0.55 | 1.04 |

| Finland | 993 | 32.81 1,2,3,4,5,7,9,10 | 6.33 | −1.15 | 2.13 |

| Germany | 1429 | 29.99 6,8,9,10 | 5.00 | −0.60 | 1.09 |

| Macedonia | 1357 | 33.93 1,2,3,4,5,7,9,10 | 4.78 | −1.16 | 2.29 |

| Poland | 1728 | 30.84 3,6,7,8 | 4.51 | −0.39 | 1.57 |

| Slovakia | 1149 | 30.68 3,6,7,8 | 5.11 | −0.56 | 1.06 |

| Total | 14,590 | 30.78 | 5.34 | −0.60 | 1.18 |

| r(HL, FAS) | r(HL, SRH) | r(SRH, FAS) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 0.21 *** | 0.18 *** | 0.11 *** |

| Belgium (Flemish) | 0.12 ** | 0.25 *** | 0.20 ** |

| Czechia | 0.11 *** | 0.27 *** | 0.13 *** |

| England | 0.17 *** | 0.23 *** | 0.17 *** |

| Estonia | 0.12 *** | 0.23 *** | 0.16 *** |

| Finland | 0.15 *** | 0.24 *** | 0.10 ** |

| Germany | 0.11 *** | 0.12 *** | 0.13 *** |

| Macedonia | 0.11 *** | 0.22 *** | 0.07 * |

| Poland | 0.12 *** | 0.16 *** | 0.03 |

| Slovakia | 0.15 *** | 0.23 *** | 0.05 |

| Total | 0.09 *** | 0.24 *** | 0.08 *** |

| Standardized Betas of Direct Effect | Standardized Betas of Indirect Effects | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 5 | ||||||

| Gender→SRH | FAS→SRH | Gender→HL | FAS→HL | HL→SRH | Gender→SRH | FAS→SRH | Gender→HL→SRH | FAS→HL→SRH | |

| Austria | −0.15 *** | 0.06 | −0.04 | 0.16 *** | 0.17 *** | −0.14 *** | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.03 *** |

| Belgium (Flemish) | −0.18 *** | 0.14 *** | −0.04 | 0.10 *** | 0.23 *** | −0.18 *** | 0.13 *** | −0.01 | 0.02 *** |

| Czechia | −0.12 *** | 0.08 *** | 0.00 | 0.09 *** | 0.26 *** | −0.13 *** | 0.07 *** | 0.00 | 0.02 *** |

| England | −0.09 * | 0.17 *** | 0.03 | 0.16 *** | 0.22 *** | −0.11 ** | 0.14 *** | 0.01 | 0.04 *** |

| Estonia | −0.13 *** | 0.12 *** | 0.10 ** | 0.12 *** | 0.25 *** | −0.18 *** | 0.10 *** | 0.02 ** | 0.03 *** |

| Finland | −0.14 *** | 0.10 ** | 0.06 | 0.13 *** | 0.25 *** | −0.14 *** | 0.06 * | 0.02 * | 0.03 ** |

| Germany | −0.13 *** | 0.08 ** | 0.04 | 0.10 *** | 0.12 *** | −0.13 *** | 0.07 * | 0.00 | 0.01 * |

| Macedonia | −0.13 *** | 0.05 * | 0.06 * | 0.09 *** | 0.24 *** | −0.14 *** | 0.03 | 0.02 * | 0.02 ** |

| Poland | −0.14 *** | 0.05 | 0.10 *** | 0.10 *** | 0.18 *** | −0.16 *** | 0.03 | 0.02 ** | 0.02 ** |

| Slovakia | −0.16 *** | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.12 *** | 0.25 *** | −0.16 *** | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 *** |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Paakkari, L.; Torppa, M.; Mazur, J.; Boberova, Z.; Sudeck, G.; Kalman, M.; Paakkari, O. A Comparative Study on Adolescents’ Health Literacy in Europe: Findings from the HBSC Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103543

Paakkari L, Torppa M, Mazur J, Boberova Z, Sudeck G, Kalman M, Paakkari O. A Comparative Study on Adolescents’ Health Literacy in Europe: Findings from the HBSC Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(10):3543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103543

Chicago/Turabian StylePaakkari, Leena, Minna Torppa, Joanna Mazur, Zuzana Boberova, Gorden Sudeck, Michal Kalman, and Olli Paakkari. 2020. "A Comparative Study on Adolescents’ Health Literacy in Europe: Findings from the HBSC Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 10: 3543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103543

APA StylePaakkari, L., Torppa, M., Mazur, J., Boberova, Z., Sudeck, G., Kalman, M., & Paakkari, O. (2020). A Comparative Study on Adolescents’ Health Literacy in Europe: Findings from the HBSC Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103543