Health-Related Disparities among Migrant Children at School Entry in Germany. How does the Definition of Migration Status Matter?

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Question

1.2. Theoretical Framework

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset

2.2. Variables

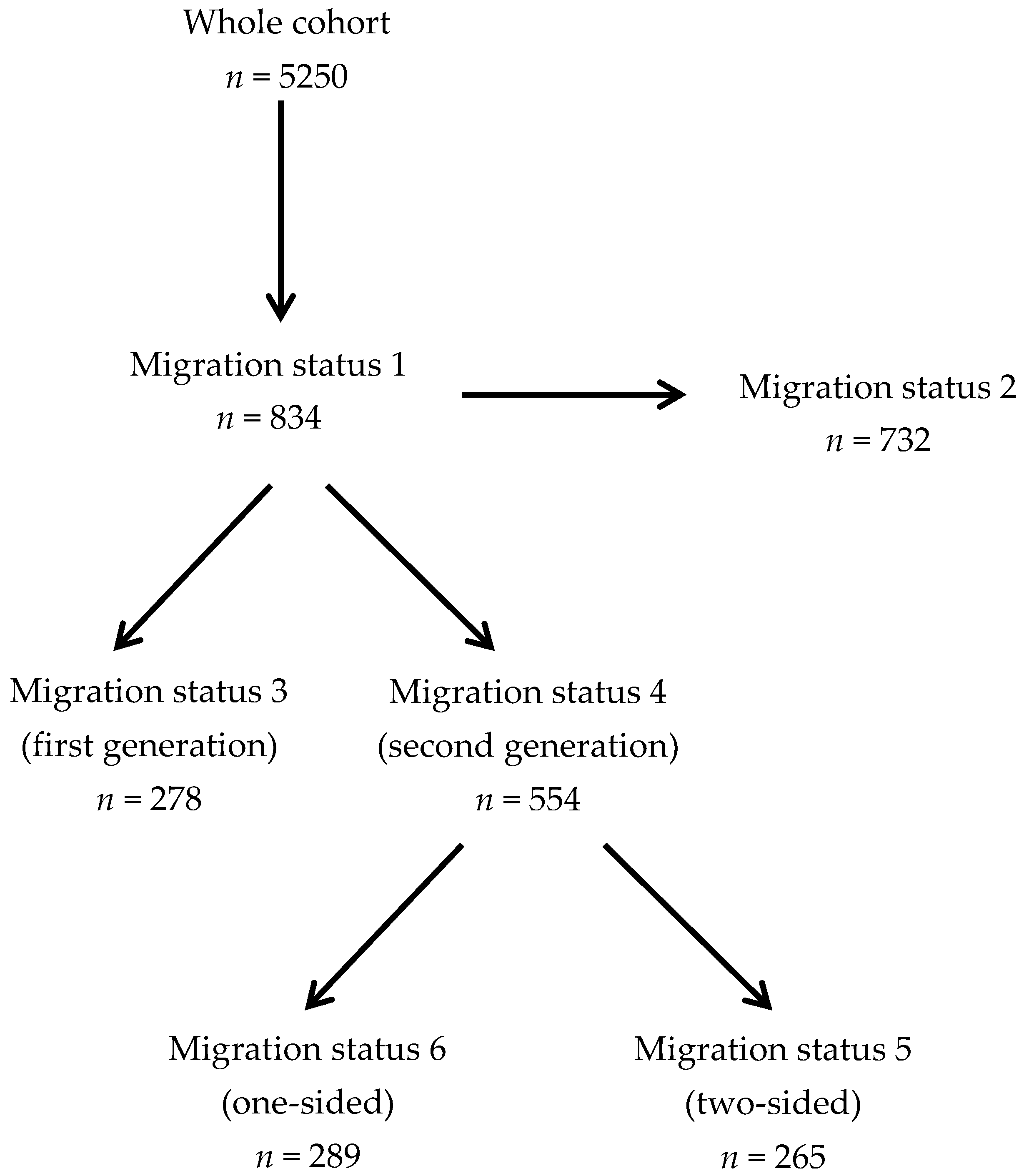

2.3. Definitions of Migration Status

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics

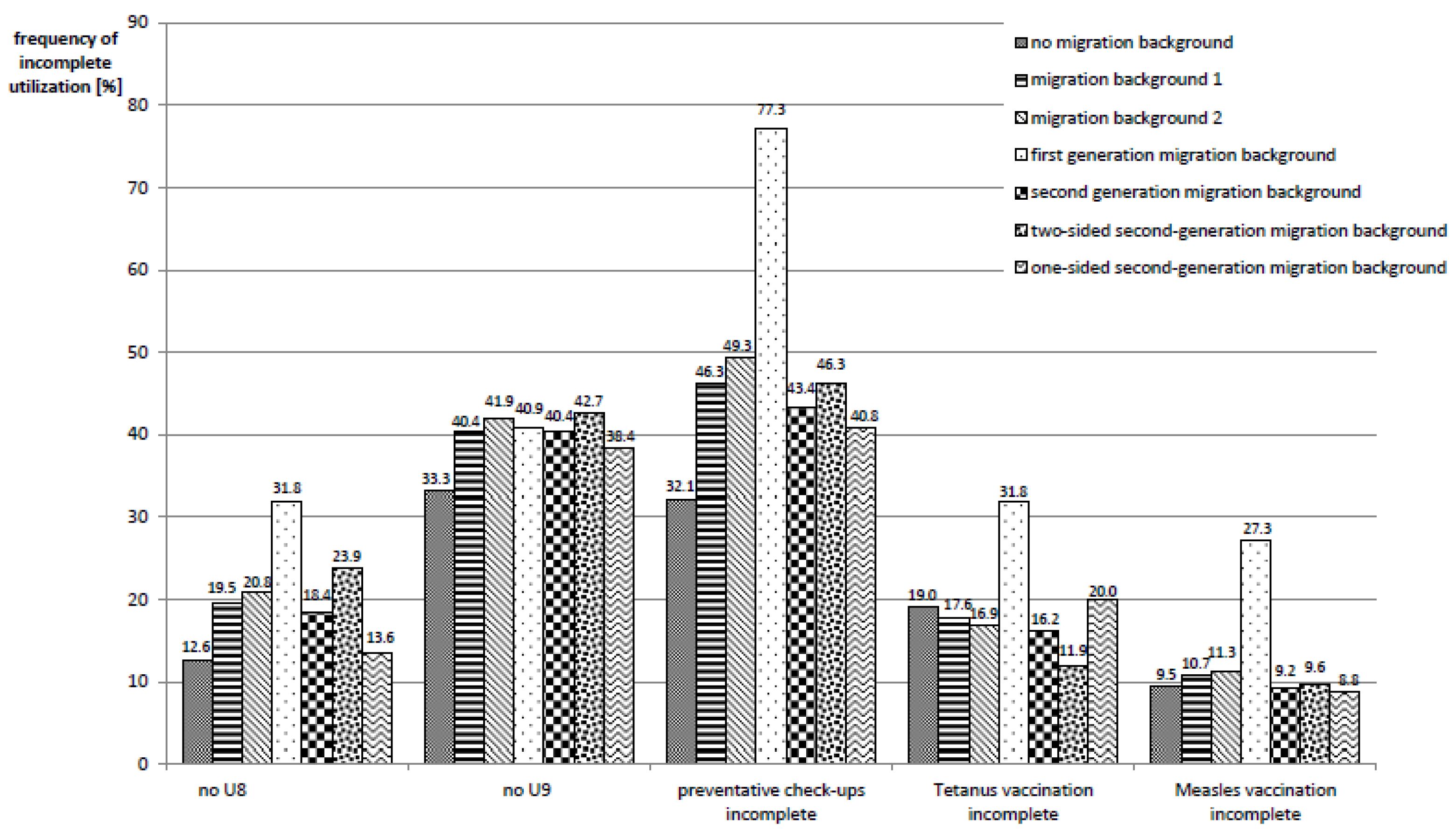

3.2. Health Service Utilization

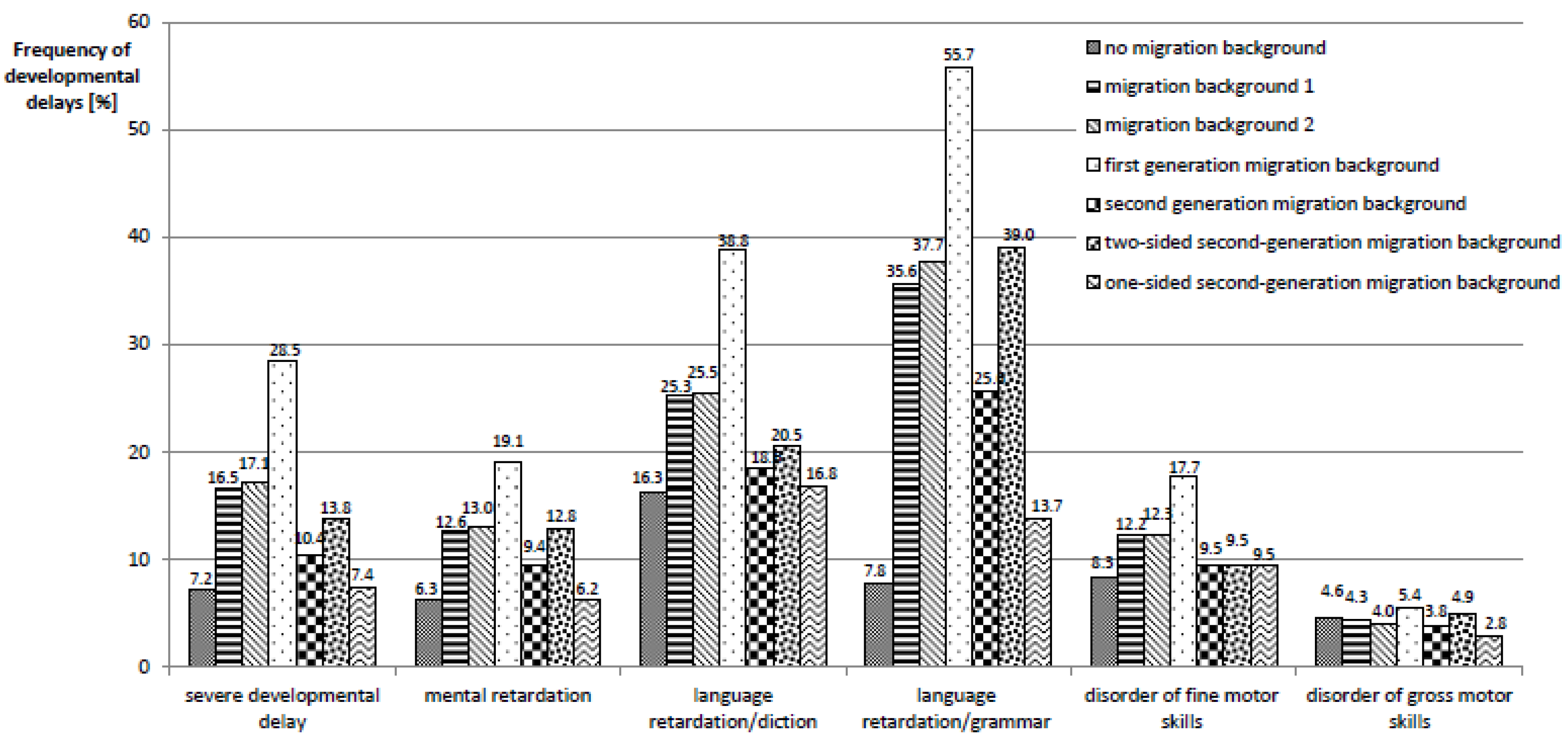

3.3. Health Outcomes

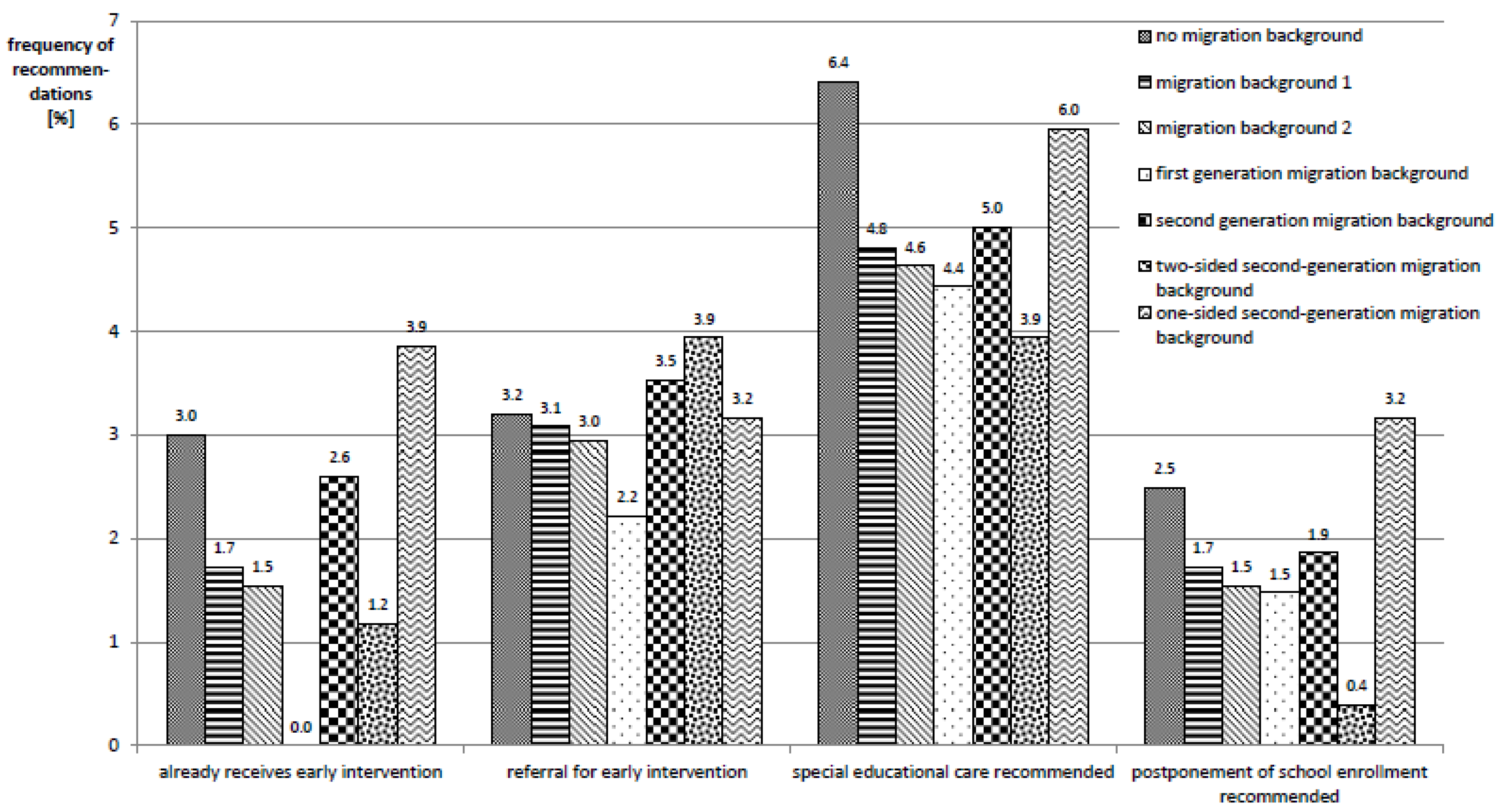

3.4. Multivariate Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- EUROSTAT. Migration and Migration Population Statistics. Available online: www.europa.eu/eurostat/statisticsexplained/index.php?title=Migration_and_migrant_population_statistics (accessed on 8 December 2019).

- Pew Research Center. Immigrant Share in U.S. Nears Record High but Remains Below That of Many Other Countries. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/01/30/immigrant-share-in-u-s-nears-record-high-but-remains-below-that-of-many-other-countries/ (accessed on 8 December 2019).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. 2015. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20151210212235/http://www.inegi.org.mx/est/contenidos/proyectos/encuestas/hogares/especiales/ei2015/doc/eic2015_resultados.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2019).

- Australian Burreau of Statistics. Australia’s Population by Country of Birth. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/3412.0Main%20Features22017-18 (accessed on 8 December 2019).

- Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Race, Ethnicity, and Language Data: Standardization for Health Care Quality Improvement; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Solé-Auró, A.; Crimmins, E.M. Health of immigrants in European countries. Int. Migr. Rev. 2008, 42, 861–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rechel, B.; Mladovsky, P.; Ingleby, D.; Mackenbach, J.P.; McKee, M. Migration and health in an increasingly diverse Europe. Lancet 2013, 381, 1235–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhugra, D. Migration and mental health. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2004, 109, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudelson, P.; Dominice, D.M.; Perneger, T.; Durieux-Paillard, S.A. “Migrant friendly hospital” initiative in Geneva, Switzerland: Evaluation of the effects on staff knowledge and practices. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e106758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alidu, L.; Grunfeld, E. A systematic review of acculturation, obesity and health behaviours among migrants to high-income countries. Psychol. Health 2018, 33, 724–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razum, O.; Geiger, I.; Zeeb, H.; Ronellenfitsch, U. Health care for migrants. Deutsches Ärzteblatt 2004, 101, 2882–2887. [Google Scholar]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Assessing the Burden of Key Infectious Diseases Affecting Migrant Populations in the EU/EEA; ECDC Technical Report; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hemminki, K. Immigrant health, our health. Eur. J. Public Health 2014, 24, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Führer, A. “Da muss sich jemand anders drum kümmern”—Die medizinische Versorgung von Asylsuchenden als Herausforderung für eine bio-psycho-soziale Medizin. Gesundheitswesen 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenkötter, N.; van Dongen, M.; Hellmeier, W.; Simon, K.; Dagnelie, P.C. The influence of migratory background and parental education on health care utilisation of children. Eur. J. Pediatrics 2012, 171, 1533–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Brzoska, P.; Razum, O. Mortality and morbidity patterns among immigrants residing in Germany. In Migration, Health and Survival: International Perspectives; Trovato, F., Ed.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2017; pp. 214–233. [Google Scholar]

- Brzoska, P. Disparities in health care outcomes between immigrants and the majority population in Germany: A trend analysis, 2006–2014. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Thi, T.G.; Heißenhuber, A.; Schneider, T.; Schulz, R.; Herr, C.E.W.; Nennstiel-Ratzel, U.; Hölscher, G. The impact of migration background on the health outcomes of preschool children: Linking a cross-sectional survey to the school entrance health examination database in Bavaria, Germany. Gesundheitswesen 2019, 81, e34–e42. [Google Scholar]

- Robert Koch Institut. Kinder- und Jugendgesundheitssurvey (KiGGS) 2003–2006: Kinder und Jugendliche mit Migrationshintergrund in Deutschland; RKI: Berlin, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Knipper, M. Migrationshintergrund? Plädoyer für eine zeitgemäße Beachtung der sozialen und kulturellen Hintergründe von Kindergesundheit in Deutschland. In Schwerpunktthema Migrantinnen und Migranten in der Pädiatrie; Bundesverband der Kinder- und Jugendärzte, e.V., Ed.; BVKJ: Köln, Germany, 2013; pp. 65–69. [Google Scholar]

- Schenk, L.; Bau, A.-M.; Borde, T.; Butler, J.; Lampert, T.; Neuhauser, H.; Razum, O.; Weilandt, C. A basic set of indicators for mapping migrant status. Recommendations for epidemiological practice. Bundesgesundheitsblatt 2006, 49, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oberwöhrmann, S.; Bettge, S.; Hermann, S. Einheitliche Erfassung des Migrationshintergrundes bei den Einschulungsuntersuchungen; Senatsverwaltung für Gesundheit und Soziales Berlin: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kemper, T. Zur Landesspezifischen Erfassung des Migrationshintergrunds in der Schulstatistik-(k)ein Gemeinsamer Nenner in Sicht? Schumpeter Discussion Papers: Wuppertal, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, V.-K. The Republic of Therapy: Triage and Sovereignty in West Africa’s Time of AIDS; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, S. Politik mit Kategorien: Zur Produktion von Differenz in Epidemiologie und Biomedizin. In Gemachte Differenz: Kontinuitäten biologischer “Rasse”-Konzepte; AG gegen Rassismus in den Lebenswissenschaften, Ed.; Unrast: Münster, Germany, 2009; pp. 278–301. [Google Scholar]

- Mays, V.M.; Ponce, N.A.; Washington, D.L.; Cochran, S.D. Classification of race and ethnicity: Implications for public health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2003, 24, 83–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistisches Bundesamt. Bevölkerung mit Migrationshintergrund—Ergebnisse des Mikrozensus 2017; Statistisches Bundesamt: Berlin, Germany, 2017.

- Führer, A.; Eichner, F. Statistics and sovereignty: The workings of biopower in epidemiology. Glob. Health Action 2015, 8, 28262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucault, M.; Senellart, M.; Ewald, F.; Fontana, A. Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1977–1978; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Hacking, I. Making up people. In Reconstructing Individualism; Heller, T., Sosna, M., Wellbery, D., Eds.; Standford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1986; pp. 161–171. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. The subject and power. Crit. Inq. 1982, 8, 777–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacking, I. Rewriting the Soul. Multiple Personality and the Sciences of Memory; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Will, A.-K. 10 Jahre Migrationshintergrund in der Repräsentativstatistik: Ein Konzept auf dem Prüfstand. Leviathan 2016, 44, 9–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollig, S.; Tervooren, A. The order of family as a preventive resource. Informal developmental diagnostic in pediatric and school entry check-ups using the example of exploring children´s television viewing. J. Sociol. Educ. Social. 2009, 29, 157–173. [Google Scholar]

- Franze, M.; Gottschling, A.; Hoffmann, W. The “Dortmund Developmental Screening for Preschools” as the basis for developmental promotion in preschools in Mecklenburg-West Pomerania. First results of the pilot project “Children in Preschools” referring to the acceptance of DESK 3–6 by preschool teachers. Bundesgesundheitsblatt 2010, 53, 1290–1297. [Google Scholar]

- Hespe-Jungesblut, K.; Jahn, N.; Bruns-Philipps, E.; Zühlke, C. Ärztliche Untersuchung vor Schulbeginn lohnt sich. Pädiatrie Hautnah 2013, 25, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossakowski, K.; Nickel, S.; Schäfer, I.; Süß, W.; Trojan, A.; Werner, S. Diagnosis of an urban quarter: Data and approaches for a quarter-oriented prevention programme in the public health sector. Präv. Gesundheitsf. 2007, 2, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weßling, A. School entrance examination: Prospects for a data-based health promotion in school and community. Gesundheitswesen 2000, 62, 383–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelle, H. Schuleingangsuntersuchungen im Spannungsfeld von Individualdiagnostik und Epidemiologie: Eine Praxisanalyse. Diskurs Kindheits- und Jugendforschung 2011, 6, 247–262. [Google Scholar]

- Spannenkrebs, M.; Crispin, A.; Krämer, D. The new preschool examination in Baden-Wurtemberg: What determinants influence the school medical evaluation special need for language promotion in childhood development? Gesundheitswesen 2013, 75, 838–847. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kelle, H. Bedeutungswandel der ärztlichen Schuleingangsuntersuchungen. Grundsch. Aktuell 2006, 9, 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Führer, A.; Wienke, A.; Tiller, D. Die Schuleingangsuntersuchung als subsidiäre Vorsorgeuntersuchung. Präv. Gesundheitsf. 2018, 143, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Führer, A.; Wienke, A.; Wiermann, S.; Gröger, C.; Tiller, D. Risk-based approach to school entry examinations in Germany—A validation study. BMC Pediatrics 2019, 19, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhm, A.; Ellsässer, G.; Lüdecke, K. The Brandenburg social index: A tool for health and social reporting at regional and communal levels in the analysis of data of school beginners. Gesundheitswesen 2007, 69, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert Koch Institut. Impfkalender (Standardimpfungen) für Säuglinge, Kinder, Jugendliche und Erwachsene 2018/2019. Epidemiol. Bull. 2018, 34, 338. [Google Scholar]

- Arbeitsgruppe Standardisierung im KJÄD 2011/2012. Handreichung für die Schuleingangsuntersuchung in Sachsen-Anhalt. 2013. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=2ahUKEwj58qPAjdPmAhX2wsQBHUT1C-cQFjAAegQIARAC&url=https%3A%2F%2Fverbraucherschutz.sachsen-anhalt.de%2Ffileadmin%2FBibliothek%2FPolitik_und_Verwaltung%2FMS%2FLAV_Verbraucherschutz%2Fservice%2Fgbe%2Fberichte%2F2018_12_Handreichung_SEU_Auszug_ohne_SEBES.pdf&usg=AOvVaw0XAa0tUnih9uSGJCOK40Dd (accessed on 26 December 2019).

- Razum, O.; Zeeb, H.; Meesmann, U.; Schenk, L.; Bredehorst, M.; Brzoska, P.; Dercks, T.; Glodny, S.; Menkhaus, S.; Salman, R.; et al. Migration und Gesundheit. Schwerpunktbericht der Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes; Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes: Berlin, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mauz, E.; Lange, M.; Houben, R.; Hoffmann, R.; Allen, J.; Gößwald, A.; Hölling, H.; Lampert, T.; Lange, C.; Poethko-Müller, C.; et al. Cohort profile: KiGGS cohort longitudinal study on the health of children, adolescents and young adults in Germany. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenland, S.; Thomas, D.C. On the need for the rare disease assumption in case-control studies. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1982, 116, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserstein, R.L.; Schirm, A.L.; Lazar, N.A. Moving to a world beyond “p < 0.05”. Am. Stat. 2019, 73, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Amrhein, V.; Greenland, S.; McShane, B. Scientists rise up against statistical significance. Nature 2019, 567, 305–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AGENS. Gute Praxis Sekundärdatenanalyse (GPS): Leitlinien und Empfehlungen; AGENS: Köln, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Stich, P.; Mikolajczyk, R.; Krämer, A. Determinanten des Teilnahmeverhaltens bei Kindervorsorgeuntersuchungen (U1–U8): Eine gesundheitswissenschaftliche Analyse zur Gesundheitsversorgung im Kindesalter. Praev. Gesundheitsf. 2009, 4, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, P.; Schöler, H.; Roos, J.; Grün-Nolz, P.; Engler-Thümmel, H. Einschulungsuntersuchung 2002 in Mannheim – Sprachentwicklungsstand bei Schulbeginn. Gesundheitswesen 2003, 2003, 676–682. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Lengerke, T.; Walter, U.; Dreier, M. Migration background and childhood overweight in the Hannover Region in 2010–2014: A population-based secondary data analysis of school entry examinations. Eur. J. Pediatrics 2018, 177, 753–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achat, H.M.; Stubbs, J.M. Socio-economic and ethnic differences in the prevalence of overweight and obesity among school children. J. Paediatrics Child Health 2014, 50, E77–E84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, E.; Ashbolt, R.; Gibbs, L.; Booth, M.; Magarey, A.; Gold, L.; Kai Lo, S.; Gibbons, K.; Green, J.; O’Connor, T.; et al. Double disadvantage: The influence of ethnicity over socioeconomic position on childhood overweight and obesity: Findings from an inner urban population of primary school children. Int. J. Pediatric Obes. 2008, 3, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, A.M.; Scarborough, P.; Galea, S. Ethnic inequalities in obesity among children and adults in the UK: A systematic review of the literature. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, e516–e534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraído-Lanza, A.F.; Armbrister, A.N.; Flórez, K.R.; Aguirre, A.N. Toward a theory-driven model of acculturation in public health research. Am. J. Public Health 2006, 96, 1342–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanenbaum, M.L.; Commissariat, P.; Kupperman, E.; Baek, R.N.; Gonzalez, J.S. Acculturation. In Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine; Gellman, M.D., Turner, J.R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesweite Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Psychosozialen Zentren für Flüchtlinge und Folteropfer. Traumatisiert. Ausgegrenzt. Unterversorgt.: Versorgungsbericht zur Situation von Flüchtlingen und Folteropfern in den Bundesländern Sachsen, Sachsen-Anhalt und Thüringen; Baff e.V.: Berlin, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Heeren, M.; Wittmann, L.; Ehlert, U.; Schnyder, U.; Maier, T.; Müller, J. Psychopathology and resident status—Comparing asylum seekers, refugees, illegal migrants, labor migrants, and residents. Compr. Psychiatry 2014, 55, 818–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Migration Status 1 | Migration Status 2 | Migration Status 3 | Migration Status 4 | Migration Status 5 | Migration Status 6 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 50.5% | 49.8% | 50.7% | 48.2% | 50.4% | 50.7% | 50.5% | 49.3% | 50.4% | 50.2% | 50.5% | 48.5% |

| Female | 49.5% | 50.2% | 49.3% | 51.9% | 49.6% | 49.3% | 49.5% | 50.7% | 49.6% | 49.8% | 49.5% | 51.5% |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||

| 4 | 7.7% | 6.6% | 7.6% | 6.9% | 7.6% | 6.7% | 7.7% | 6.5% | 7.7% | 4.8% | 7.6% | 7.8% |

| 5 | 84.8% | 85.8% | 84.8% | 86.2% | 85.0% | 84.7% | 84.9% | 86.3% | 84.8% | 89.9% | 84.8% | 83.6% |

| 6 | 7.4% | 7.6% | 7.5% | 6.9% | 7.4% | 8.6% | 7.4% | 7.2% | 7.5% | 5.3% | 7.5% | 8.6% |

| Socio-Economic Status * | ||||||||||||

| High | 46.4% | 38.5% | 46.7% | 35.4% | 46.2% | 24.9% | 46.4% | 44.6% | 45.5% | 38.7% | 45.3% | 49.3% |

| Medium | 34.9% | 28.3% | 34.7% | 29.3% | 34.4% | 25.4% | 34.9% | 29.7% | 34.3% | 28.0% | 34.5% | 31.0% |

| Low | 18.7% | 33.1% | 18.7% | 35.4% | 19.5% | 49.8% | 18.7% | 25.7% | 20.2% | 33.3% | 20.3% | 19.8% |

| Type of Child Care | ||||||||||||

| Kindergarten | 96.8% | 85.1% | 96.6% | 84.9% | 96.8% | 60.3% | 96.8% | 96.0% | 95.2% | 94.7% | 95.0% | 97.0% |

| At home | 3.0% | 14.7% | 3.2% | 15.0% | 3.1% | 39.2% | 3.0% | 4.0% | 4.7% | 5.3% | 4.8% | 3.0% |

| Nanny | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.1% | 0.5% | 0.2% | . | 0.2% | . | 0.2% | . |

| Parents’ Marital Status | ||||||||||||

| No information | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.2% | 1.0% | 0.2% | . | |

| Single mother | 22.4% | 18.4% | 22.2% | 19.0% | 22.3% | 10.5% | 22.3% | 21.9% | 22.2% | 12.1% | 21.8% | 29.5% |

| Mother and new partner | 6.3% | 3.2% | 6.2% | 3.0% | 6.0% | 1.9% | 6.3% | 3.8% | 6.0% | 1.5% | 6.0% | 5.6% |

| Both parents | 68.6% | 76.8% | 68.9% | 76.3% | 67.0% | 87.6% | 68.6% | 72.0% | 69.1% | 85.0% | 69.5% | 61.9% |

| other | 2.6% | 1.3% | 2.6% | 1.4% | 2.6% | 2.6% | 1.9% | 2.5% | 0.5% | 2.5% | 3.0% | |

| Number of Siblings | ||||||||||||

| <3 | 88.3% | 80.2% | 88.2% | 79.5% | 87.7% | 75.1% | 87.7% | 82.3% | 87.3% | 83.1% | 87.4% | 81.7% |

| ≥3 | 11.7% | 19.9% | 11.8% | 20.5% | 12.3% | 24.9% | 12.4% | 17.7% | 12.7% | 16.9% | 12.6% | 18.3% |

| Mother’s Country of Origin | Migration Status 1 | Migration Status 2 | Migration Status 3 | Migration Status 4 | Migration Status 5 | Migration Status 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germany | 206 (24.8%) | 159 (21.8%) | 16 (5.8%) | 190 (34.4%) | 1 (0.4%) | 189 (65.6%) |

| Syria | 150 (18.0%) | 144 (19.7%) | 119 (42.8%) | 31 (5.6%) | 31 (11.7%) | 0 |

| Russia | 48 (5.8%) | 42 (5.8%) | 6 (2.2%) | 42 (7.6%) | 27 (10.2%) | 15 (5.2%) |

| Turkey | 42 (5.1%) | 39 (5.3%) | 2 (0.7%) | 40 (7.2%) | 40 (15.1%) | 0 |

| Vietnam | 41 (4.9%) | 41 (5.6%) | 2 (0.7%) | 39 (7%) | 33 (12.5%) | 6 (2.1%) |

| Poland | 24 (2.9%) | 21 (2.9%) | 11 (4%) | 13 (2.4%) | 3 (1.1%) | 10 (3.5%) |

| Ukraine | 22 (2.6%) | 20 (2.7%) | 6 (2.2%) | 16 (2.9%) | 13 (4.9%) | 3 (1%) |

| Iraq | 19 (2.3%) | 16 (2.2%) | 1 (0.4%) | 18 (3.3%) | 17 (6.4%) | 1 (0.4%) |

| Kosovo | 18 (2.2%) | 18 (2.5%) | 2 (0.7%) | 16 (2.9%) | 15 (5.7%) | 1 (0.4%) |

| Kazakhstan | 15 (1.8%) | 11 (1.5%) | 1 (0.4%) | 14 (2.5%) | 11 (4.2%) | 3 (1%) |

| Father’s Country of Origin | ||||||

| Syria | 158 (19%) | 149 (20.5%) | 120 (43.3%) | 38 (6.9%) | 32 (12.1%) | 6 (2.1%) |

| Germany | 110 (13.3%) | 85 (11.7%) | 22 (7.9%) | 88 (16%) | 1 (0.4%) | 87 (30.4%) |

| Nigeria | 56 (6.8%) | 51 (7%) | 3 (1.1%) | 53 (9.6%) | 8 (3%) | 45 (15.7%) |

| Turkey | 54 (6.5%) | 51 (7%) | 4 (1.4%) | 50 (9%) | 41 (15.5%) | 9 (3.2%) |

| Russia | 35 (4.2%) | 26 (3.6%) | 3 (1.1%) | 32 (5.8%) | 23 (8.7%) | 9 (3.2%) |

| Vietnam | 34 (4.1%) | 34 (4.7%) | 1 (0.4%) | 33 (6%) | 33 (12.5%) | 0 |

| Iraq | 32 (3.9%) | 29 (4%) | 1 (0.4%) | 31 (5.6%) | 17 (6.4%) | 14 (4.9%) |

| Kosovo | 19 (2.3%) | 19 (2.6%) | 1 (0.4%) | 18 (3.3%) | 16 (6%) | 2 (0.7%) |

| Ukraine | 17 (2.1%) | 16 (2.2%) | 1 (0.4%) | 16 (2.9%) | 12 (4.5%) | 4 (1.4%) |

| India | 16 (1.9%) | 15 (2.1%) | 10 (3.6%) | 6 (1.1%) | 2 (0.8%) | 4 (1.4%) |

| No Preventative Checkup U8 | Incomplete Tetanus Vaccination | Severe Developmental Delay | Special Educational Care Recommended | Referral for Early Intervention | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude PR * (95%-CI) | Adjusted PR *,† (95%-CI) | Crude PR * (95%-CI) | Adjusted PR *,† (95%-CI) | Crude PR * (95%-CI) | Adjusted PR *,† (95%-CI) | Crude PR * (95%-CI) | Adjusted PR *,† (95%-CI) | Crude PR * (95%-CI) | Adjusted PR *,† (95%-CI) | |

| Migration status 1 | 1.57 (1.30–1.88) | 1.57 (1.29–1.90) | 2.14 (1.93–2.37) | 2.02 (1.81–2.26) | 2.22 (1.86–2.65) | 1.57 (1.29–1.90) | 0.76 (0.55–1.03) | 0.59 (0.42–0.82) | 0.96 (0.64–1.45) | 0.74 (0.47–1.17) |

| Migration status 2 | 1.66 (1.38–2.01) | 1.61 (1.31–1.98) | 2.25 (2.03–2.49) | 2.13 (1.9–2.38) | 2.32 (1.93–2.77) | 1.58 (1.30–1.93) | 0.72 (0.51–1.01) | 0.56 (0.39–0.79) | 0.93 (0.6–1.44) | 0.69 (0.43–1.13) |

| Migration status 3 | 2.35 (1.51–3.65) | 3.05 (1.97–4.73) | 3.83 (3.49–4.21) | 3.56 (3.2–3.96) | 3.69 (3.01–4.54) | 2.16 (1.73–2.69) | 0.75 (0.45– 1.27) | 0.44 (0.25–0.79) | 0.78 (0.37–1.64) | 0.42 (0.18–1.02) |

| Migration status 4 | 1.49 (1.23–1.82) | 1.47 (1.2–1.81) | 1.28 (1.09–1.5) | 1.31 (1.1–1.55) | 1.47 (1.15–1.89) | 1.14 (0.87–1.51) | 0.76 (0.52–1.1) | 0.68 (0.46–1.00) | 1.06 (0.66–1.7) | 0.95 (0.58–1.58) |

| Migration status 5 | 1.85 (1.45–2.35) | 1.77 (1.36–2.3) | 1.25 (0.99–1.56) | 1.28 (0.99–1.64) | 2.05 (1.54–2.74) | 1.41 (1.02–1.95) | 0.62 (0.35–1.12) | 0.52 (0.29–0.96) | 1.17 (0.62–2.19) | 0.80 (0.38–1.68) |

| Migration status 6 | 1.19 (0.89–1.59) | 1.22 (0.91–1.65) | 1.31 (1.06–1.61) | 1.34 (1.08–1.66) | 0.94 (0.62–1.42) | 0.85 (0.54–1.34) | 0.88 (0.55–1.42) | 0.85 (0.52–1.38) | 0.96 (0.5–1.87) | 1.1 (0.57–2.1) |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Führer, A.; Tiller, D.; Brzoska, P.; Korn, M.; Gröger, C.; Wienke, A. Health-Related Disparities among Migrant Children at School Entry in Germany. How does the Definition of Migration Status Matter? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 212. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17010212

Führer A, Tiller D, Brzoska P, Korn M, Gröger C, Wienke A. Health-Related Disparities among Migrant Children at School Entry in Germany. How does the Definition of Migration Status Matter? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(1):212. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17010212

Chicago/Turabian StyleFührer, Amand, Daniel Tiller, Patrick Brzoska, Marie Korn, Christine Gröger, and Andreas Wienke. 2020. "Health-Related Disparities among Migrant Children at School Entry in Germany. How does the Definition of Migration Status Matter?" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 1: 212. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17010212

APA StyleFührer, A., Tiller, D., Brzoska, P., Korn, M., Gröger, C., & Wienke, A. (2020). Health-Related Disparities among Migrant Children at School Entry in Germany. How does the Definition of Migration Status Matter? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(1), 212. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17010212