Mothers’ Understanding of Infant Feeding Guidelines and Their Associated Practices: A Qualitative Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection

- Solid food considerations before baby was born, age of starting

- Importance of introducing solid food

- Experiences of the first day, planning and emotions

- Information, events and infant behaviour used to direct personal practices

- Mother’s perception of her infant’s needs

- Interpretation of infant temperament and behaviour—signs of readiness for solid food

- People, events, barriers or facilitators which prevented or assisted the achievement of their feeding intentions (Mind mapping of influencers)

- Experiences with baby foods—suitability of foods and textures (texture photos prompt)

- Women’s awareness of current infant feeding recommendations and of the scientific rationale for the recommendations

- Personal beliefs about the appropriateness and relevance of guidelines

2.4. Ethical Considerations

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Knowledge of the Australian Infant Feeding Guidelines

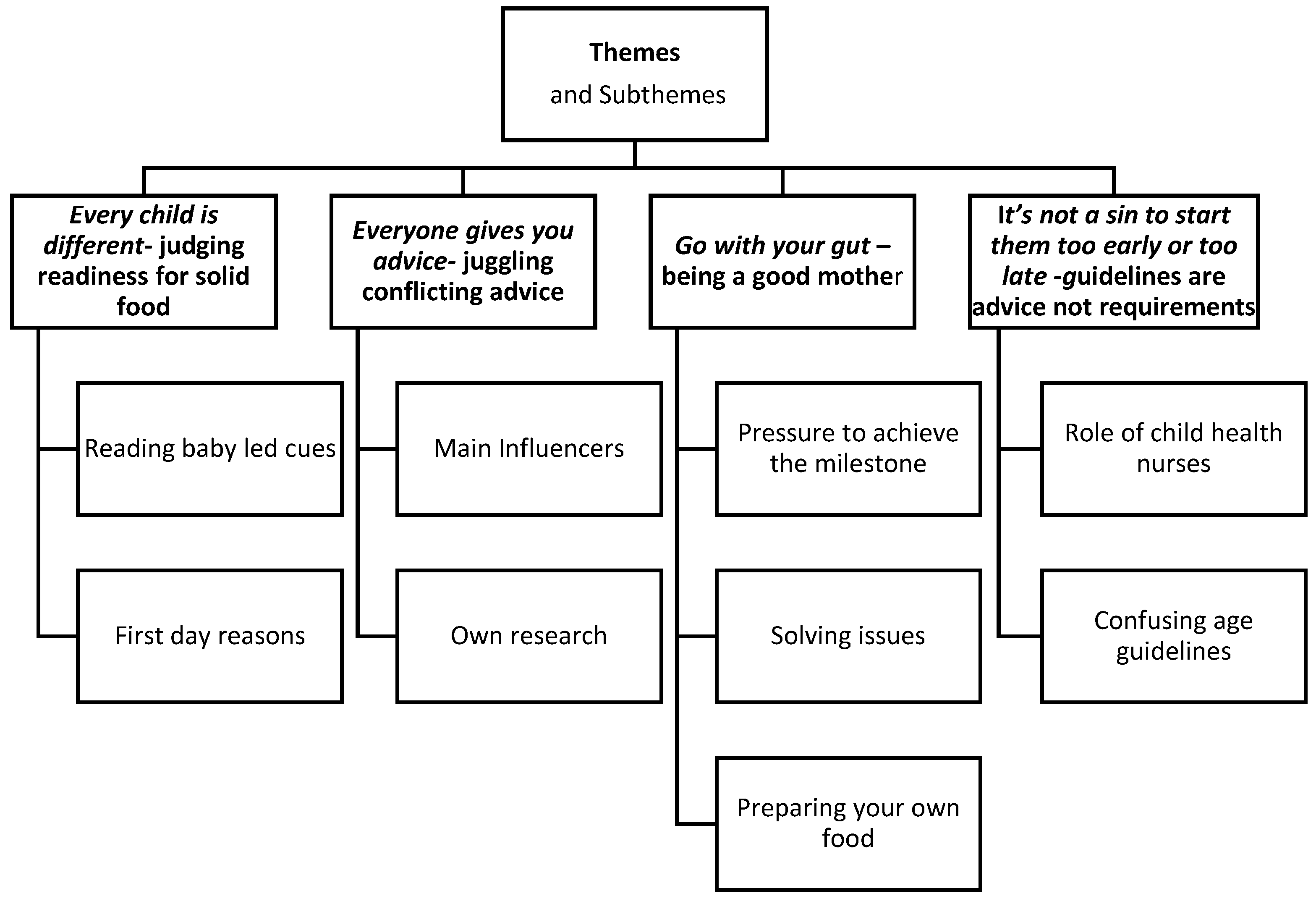

3.3. Themes and Sub Themes

3.3.1. Theme 1: Every child is different—judging readiness for solid food

Subtheme—Reading Baby Led Cues

They are this person, you have to kind of go with how the child reacts. Like it doesn’t concern me when (baby name) doesn’t eat something because I’m not going to eat everything and do you know what I mean she’s just a tiny person and she’s got her own what she likes and what she doesn’t like.(FG6 Participant 3)

‘cause she was doing the stare thing me and my husband I kept coming to him, should we do it, and he’d just go whatever you think and I’d go but I don’t know what do you think and he’d just go whatever you think. You know it says 4–6 months and we did it (introduce at 4 ½ months) because she’d stare at us when we eat in front of her.(FG2 Participant 6)

… saying that you know the food had to be led by the baby, so introducing food was always had to be after a feed and had to be you know led by the baby. So according to quantity, quantity, what they ate, their likes and dislikes, and something else I can’t even remember what it was but yeah.(FG5 Participant 3)

Subtheme—First Day Reasons

You know it was just, it was a spur of the moment kind of.(FG5-Patricipant 2)

3.3.2. Theme 2: Everyone gives you advice—juggling conflicting advice

Subtheme—Main Influencers

… that had a huge impact ‘cause then I felt like I had the approval of, their approval oh I’m not stupid in thinking that I should be doing this. So it was, yeah it was nice too.(FG5 Participant 3)

Whereas with my youngest one it was I don’t know if it was almost like if everyone else is doing it them I felt that I should be.(FG3 Participant 1)

Mine always wanted to feed him. I’d say no you’re not feeding him yet, ‘can I feed him now’, no not yet.(FG5-Participant 1)

Subtheme—Own Research

I started thinking about solids probably when she was a few months old, started doing that research and looking into the guidelines and trying to work out what sort of approach I wanted to take to it…(FG4 participant 1)

I’m just sick of all of the conflicting, like having to explain what I’m doing to everyone and why, like everyone just tries to tell me what to do. Like my husband will say why haven’t you given her this or why did you give her this or what are you doing with this and then I’ll try to explain to him and then my parents will say what are you doing, why are you doing this.(FG2 Participant 2)

3.3.3. Theme 3: Go with Your Gut—Being a Good Mother

You’re not doing it to harm your child I think that you’ve got that innate fear that you’re doing everything wrong as a mum you know….(FG4-Participant 2)

My obstetrician told me to like go with my gut, like be, ignore a lot of, don’t over research, don’t over analyse, do what you’re most comfortable with.(FG7- Participant 2)

Subtheme—Pressure to Achieve the Milestone

Oh I think we were all very excited it was a big milestone. For me it was a big milestone, it’s like wow suddenly he can eat things what’s going on he can’t just have milk anymore he needs something else.(FG2-Participant 1)

You want your child to be winning the race.(FG6-Participant 7)

I just felt that a couple of girls in our mother’s group they just really wanted to push their babies anyway so they just couldn’t wait for them to crawl, couldn’t wait for them roll, it was just kind of generally speed up the process rather than just like let it happen so…(FG7-Participant 3)

You’re not hearing about the average child you’re hearing about the geniuses and the ones that, the extremes.(FG7-Participant 2)

Subtheme—Solving Issues

Mine started as a weight issue, we dropped off the scale and needed, were told basically to start…(FG5-Partcipant 3)

You’re told that they will sleep through the night if you give them more solids during the day.(FG2 Participant 1)

I’m a terrible cook. I’m just, I’m not particularly good cook and although I did you know my own apple, mashed up apple and a few things like that just to give a bit more variety and to get the meat, because I didn’t know how to puree it…(FG7-Participant 2)

Subtheme—Preparing Own Food

So with the baby food like they say organic, you don’t know if it is organic. They say that this is in there but it might not be in there and they say that like these fresh veggies but it might be like old, you just don’t know. It’s like hard to trust so you’d rather trust your own cooking than a jar of baby food.(FG4 Participant 4)

Just goes to show then no two are the same are they?(FG3 Participant 1)

3.3.4. Theme 4: It’s not a Sin to Start them too Early or too Late—Guidelines are Advice not Requirements

I think they need to set guidelines to let people know that it’s ok to vary it from the guidelines. That it’s not a sin to start them too early or too late.(FG5- Participant 1)

Follow like the guidelines you know what they should eat at what stage but then I guess because seeing her, what she was capable of eating, from there I just made up my own mind and like you know and what she could handle so I kind of just, the guidelines went out the window for me.(FG4-Participant 3)

Subtheme—Role of Child Health Nurses

They just basically tell you when the child’s ready that’s when you put your child on solids and there’s not any specific guidelines, they just look at as every child’s different sort of thing.(FG6-Participant 3)

We’ve got a child health nurse and they go the guideline says 6 months but we kind of know that it’s really 4, 4½ months where they start showing signs that they’re ready. You need to pay attention to the signs.(FG2-Participant 1)

Subtheme Confusing Age Guidelines

‘cause I’ve never had any guidelines, I’ve never been to see a child health nurse, I was told by a doctor that I need to do that so I’ve no idea. So I just go, I see it in the shop it says 4 months and I’m sweet, she’s 4 months, done.(FG5-Participant 5)

(Guidelines)… change so regularly they’re all just forever going back and forth on what it should be so you can’t really take too much with that.(FG4-Participant1)

4. Discussion

4.1. Signs of Readiness

4.2. Sources of Information

4.3. Being a Good Mother

4.4. Role of Infant Feeding Guidelines

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Dietary Guidelines for Australian Adults; Commonwealth Department of Health and Aging: Canberra, Australia, 2003.

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Infant Feeding Guidelines; National Health and Medical Research Council: Canberra, Australia, 2012.

- Donath, S.M.; Amir, L.H. Breastfeeding and the introduction of solids in australian infants: Data from the 2001 national health survey. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2005, 29, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.A.; Binns, C.W.; Graham, K.I.; Oddy, W.H. Predictors of the early introduction of solid foods in infants: Results of a cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2009, 9, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2010 Australian National Infant Feeding Survey: Indicator Results; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Canberra, Australia, 2011.

- Newby, R.; Davies, P. A prospective study on the introduction of complementary foods in comtemporary australian infants: What, when and why? J. Paediatr. Child Health 2015, 51, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, L.M.; Baur, L.A.; Rissel, C.; Alperstein, G.; Simpson, J.M. Intention to breastfeed and awareness of health recommendations: Findings from first-time mothers in southwest sydney, australia. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2009, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupton, D.A. ‘The best thing for the baby’: Mothers’ concepts and experiences related to promoting their infants’ health and development. Health Risk Soc. 2011, 13, 637–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauck, Y.L.; Graham-Smith, C.; McInerney, J.; Kay, S. Western australian women’s perceptions of conflicting advice around breast feeding. Midwifery 2011, 27, e156–e162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, E.; Hoban, E. Infant feeding intentions among first time pregnant women in urban melbourne, australia. Midwifery 2013, 29, 787–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brouwer, M.A.; Drummond, C.; Willis, E. Using goffman’s theories of social interaction to reflect first-time mothers’ experiences with the social norms of infant feeding. Qual. Health Res. 2012, 22, 1345–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, M.; Brodribb, W.; Hepworth, J. A qualitative systematic review of maternal infant feeding practices in transitioning from milk feeds to family foods. Matern. Child Nutr. 2017, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zehle, K.; Wen, L.M.; Orr, N.; Rissel, C. “It’s not an issue at the moment”: A qualitative study of mothers about childhood obesity. MCN Am. J. Matern. Child Nurs. 2007, 32, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Matvienko-Sikar, K.; Kelly, C.; Sinnott, C.; McSharry, J.; Houghton, C.; Heary, C.; Toomey, E.; Byrne, M.; Kearney, P.M. Parental experiences and perceptions of infant complementary feeding: A qualitative evidence synthesis. Obes. Rev. 2018, 19, 501–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuswara, K.; Laws, R.; Kremer, P.; Hesketh, K.D.; Campbell, K.J. The infant feeding practices of chinese immigrant mothers in australia: A qualitative exploration. Appetite 2016, 105, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, C.G.; Taki, S.; Azadi, L.; Campbell, K.J.; Laws, R.; Elliott, R.; Denney-Wilson, E. A qualitative study of the infant feeding beliefs and behaviours of mothers with low educational attainment. BMC Pediatr. 2016, 16, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, A.; Kearney, L.; Dennis, N. Factors influencing first-time mothers’ introduction of complementary foods: A qualitative exploration. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, A.C.; Hesketh, K.D.; Crawford, D.A.; Campbell, K.J. Mothers’ perceptions of the influences on their child feeding practices—A qualitative study. Appetite 2016, 105, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, M.; Hepworth, J.; Brodribb, W. Navigating motherhood and maternal transitional infant feeding: Learnings for health professionals. Appetite 2018, 121, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillie, L. Promoting and evaluating scientific rigour in qualitative research. Nurs. Stand. 2015, 29, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (coreq): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, E. Risk, responsiblity and rhetoric in infant feeding. J. Contemp. Ethnogr. 2000, 29, 291–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisogni, C.A.; Jastran, M.; Seligson, M.; Thompson, A. How people interpret healthy eating: Contributions of qualitative research. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2012, 44, 282–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.R. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am. J. Eval. 2016, 27, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, A.; Swift, J.A. Qualitative research in nutrition and dietetics: Data collection issues. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2011, 24, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.; Binns, C.W.; Arnold, R. Attitudes towards breastfeeding in Perth, Australia qualitative analysis. J. Nutr. Educ. 1997, 29, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.A.; Mostyn, T.; Greater Glasgow Breastfeeding Initiative Management Team. Women’s experiences of breastfeeding in a bottle-feeding culture. J. Hum. Lact. 2003, 19, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tattersall, C.; Watts, A.; Vernon, S. Mind mapping as a tool in qualitative research. Nurs. Times 2007, 103, 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, D. Talking about pictures: A case for photo elicitation. Vis. Stud. 2002, 17, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Resarch; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.; Huberman, A. Qualitative Data Analysis; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Maternal and Child Health Unit. Western Australia’s Mothers and Babies, 2013. 31st Annual Report of the Western Australian Midwives’ Notification System; Department of Health, Government of Western Australia: East Perth, WA, Australia, 2016.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Census of population and housing (2016), TableBuilder. Findings based on the use of the abs TableBuilder data. Available online: http://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/censushome.nsf/home/tablebuilder?opendocument&navpos=240 (accessed on 29 March 2016).

- Schwartz, C.; Scholtens, P.A.; Lalanne, A.; Weenen, H.; Nicklaus, S. Development of healthy eating habits early in life. Review of recent evidence and selected guidelines. Appetite 2011, 57, 796–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, A.S.; Guthrie, C.A.; Alder, E.M.; Forsyth, S.; Howie, P.W.; Williams, F.L. Rattling the plate--reasons and rationales for early weaning. Health Educ. Res. 2001, 16, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arden, M.A. Conflicting influences on UK mothers’ decisions to introduce solid foods to their infants. Matern. Child Nutr. 2010, 6, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.; Rowan, H. Maternal and infant factors associated with reasons for introducing solid foods. Matern. Child Nutr. 2016, 12, 500–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locke, A. Agency, ‘good motherhood’ and ‘a load of mush’: Constructions of baby-led weaning in the press. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 2015, 53, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A.P.; Milligan, P.; Goff, L.M. An online survey of knowledge of the weaning guidelines, advice from health visitors and other factors that influence weaning timing in UK mothers. Matern. Child Nutr. 2014, 10, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, J.; Bower, K.M.; Spence, M.; Kavanagh, K.F. Using grounded theory methodology to conceptualize the mother-infant communication dynamic: Potential application to compliance with infant feeding recommendations. Matern. Child Nutr. 2015, 11, 749–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapley, G. Baby-led weating. A developmental approach to the introduction of complementary foods. In Maternal and Infant Nutrition and Nuture. Controversies and Challenges; Hall Moran, V., Dykes, F., Eds.; Quay Books: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, S.L.; Taylor, R.W.; Heath, A.L. Parent-led or baby-led? Associations between complementary feeding practices and health-related behaviours in a survey of New Zealand families. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e003946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapley, G. Baby-led weaning: Transitioning to solid foods at the baby’s own pace. Community Pract. 2011, 84, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, A.; Michaelsen, K.F.; Holm, L. Beyond an assumed mother–child symbiosis in nutritional guidelines: The everyday reasoning behind complementary feeding decisions. Child Care Pract. 2014, 20, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newby, R.; Brodribb, W.; Ware, R.S.; Davies, P.S. Antenatal information sources for maternal and infant diet. Breastfeed. Rev. 2015, 25, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ashida, S.; Lynn, F.B.; Williams, N.A.; Schafer, E.J. Competing infant feeding information in mothers’ networks: Advice that supports v. Undermines clinical recommendations. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caton, S.J.; Ahern, S.M.; Hetherington, M.M. Vegetables by stealth. An exploratory study investigating the introduction of vegetables in the weaning period. Appetite 2011, 57, 816–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gage, H.; Williams, P.; Von Rosen-Von Hoewel, J.; Laitinen, K.; Jakobik, V.; Martin-Bautista, E.; Schmid, M.; Egan, B.; Morgan, J.; Decsi, T.; et al. Influences on infant feeding decisions of first-time mothers in five european countries. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 66, 914–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, T. “Is this what motherhood is all about?” Weaving expriences and discourse through transition to first-time motherhood. Gend. Soc. 2007, 21, 337–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, A.; Schmied, V.; Barclay, L. Exploring the process of women’s infant feeding decisions in the early postbirth period. Qual. Health Res. 2013, 23, 989–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoddinott, P.; Craig, L.C.; Britten, J.; McInnes, R.M. A serial qualitative interview study of infant feeding experiences: Idealism meets realism. BMJ Open 2012, 2, e000504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moisio, R.; Arnould, E.; Price, L. Between mothers and markets: Constructing family identify through homemade food. J. Consum. Cult. 2004, 4, 361–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A. Too many cooks spoil the broth? Mother’s authority on food and feeding. Advert. Soc. Rev. 2006, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, M.; Brembeck, H. Best for baby? Framing weaning practice and motherhood in web-mediated marketing. Consum. Markets Cult. 2016, 20, 153–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, K.; Daniels, L.; Murray, N.; White, K.M.; Walsh, A. Mothers’ perceptions of introducing solids to their infant at six months of age: Identifying critical belief-based targets to promote adherence to current infant feeding guidelines. J. Health Psychol. 2012, 17, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunford, E.; Louie, J.C.; Byrne, R.; Walker, K.Z.; Flood, V.M. The nutritional profile of baby and toddler food products sold in australian supermarkets. Matern. Child Health J. 2015, 19, 2598–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaak, S.J. Contextualising risk, constructing choice: Breastfeeding and good mothering in risk society. Health Risk Soc. 2010, 12, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Key, V.; Hugh-Jones, S. I don’t need anybody to tell me what I should be doing. A discursive analysis of maternal accounts of (mis)trust of healthy eating information. Appetite 2010, 54, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Synnott, K.; Bogue, J.; Edwards, C.A.; Scott, J.A.; Higgins, S.; Norin, E.; Frias, D.; Amarri, S.; Adam, R. Parental perceptions of feeding practices in five european countries: An exploratory study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 61, 946–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peckover, S.; Aston, M. Examining the social construction of surveillance: A critical issue for health visitors and public health nurses working with mothers and children. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, e379–e389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographic Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Mother’s age (yrs) | ||

| <25 | 9 | 21.4 |

| 25–29 | 11 | 26.2 |

| 30–34 | 11 | 26.2 |

| 35+ | 11 | 26.2 |

| Mother’s level of education | ||

| <10 yrs | 2 | 4.8 |

| Year 10 or equivalent | 1 | 2.4 |

| Year 12 or equivalent | 6 | 14.3 |

| Trade/diploma | 13 | 31.0 |

| Bachelor degree or higher | 18 | 42.9 |

| Missing | 2 | 4.8 |

| Infant age (months) | ||

| <6 | 6 | 14.3 |

| 6–8 | 13 | 31.0 |

| 9–11 | 11 | 26.2 |

| ≥ 12 | 12 | 28.6 |

| Age solid food introduced (months) | ||

| <4 | 5 | 11.9 |

| 4 to <6 | 29 | 69.0 |

| ≥6 | 8 | 19.0 |

| Age stopped breastfeeding (months) (n = 22) | ||

| <2 | 8 | 36.4 |

| 2–3 | 6 | 27.3 |

| 4–5 | 3 | 13.6 |

| ≥ 6 | 5 | 22.7 |

| Age received formula (months) (n = 29) | ||

| <4 | 25 | 59.5 |

| 4 to <6 | 3 | 7.1 |

| ≥6 | 14 | 33.3 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Begley, A.; Ringrose, K.; Giglia, R.; Scott, J. Mothers’ Understanding of Infant Feeding Guidelines and Their Associated Practices: A Qualitative Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1141. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16071141

Begley A, Ringrose K, Giglia R, Scott J. Mothers’ Understanding of Infant Feeding Guidelines and Their Associated Practices: A Qualitative Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(7):1141. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16071141

Chicago/Turabian StyleBegley, Andrea, Kyla Ringrose, Roslyn Giglia, and Jane Scott. 2019. "Mothers’ Understanding of Infant Feeding Guidelines and Their Associated Practices: A Qualitative Analysis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 7: 1141. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16071141

APA StyleBegley, A., Ringrose, K., Giglia, R., & Scott, J. (2019). Mothers’ Understanding of Infant Feeding Guidelines and Their Associated Practices: A Qualitative Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(7), 1141. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16071141