Factors Forming the Consumers’ Willingness to Pay a Price Premium for Ecological Goods in Ukraine

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- The subject literature review and the research objective formulation,

- Developing the questionnaire (survey),

- Conducting surveys in the selected cities,

- The analysis of collected results using the descriptive method and the statistical inference method,

- The identification of factors affecting consumers’ willingness to pay a price premium and the verification of the research theses.

3. Results and Discussion

- -

- cosmetics: χ2(3, N = 200) = 13.87; p < 0.010; V = 0.27—it means that the respondents aged 31–40 were more likely to use ecological cosmetics than the ones representing other age groups, whereas people aged over 50 were less likely to use such products compared to younger age groups;

- -

- packaging and bags: χ2(3, N = 200) = 14.36; p < 0.010; V = 0.28—it means that the respondents aged 31–40 used ecological packaging and bags more often than the ones in other age groups, whereas people aged over 50 used such products less often compared to younger age groups.

- Insufficient awareness of consumers regarding the concept of “ecological goods” and the lack of willingness to purchase them: χ2(4, N = 199) = 12.29; p < 0.050; V = 0.29. This means that pensioners less often than manual labourers, entrepreneurs, unemployed, and pupils/students pointed to the insufficient awareness of customers regarding “ecological goods” and the lack of willingness to purchase them as a current problem with the market for environmental goods (Figure 3);

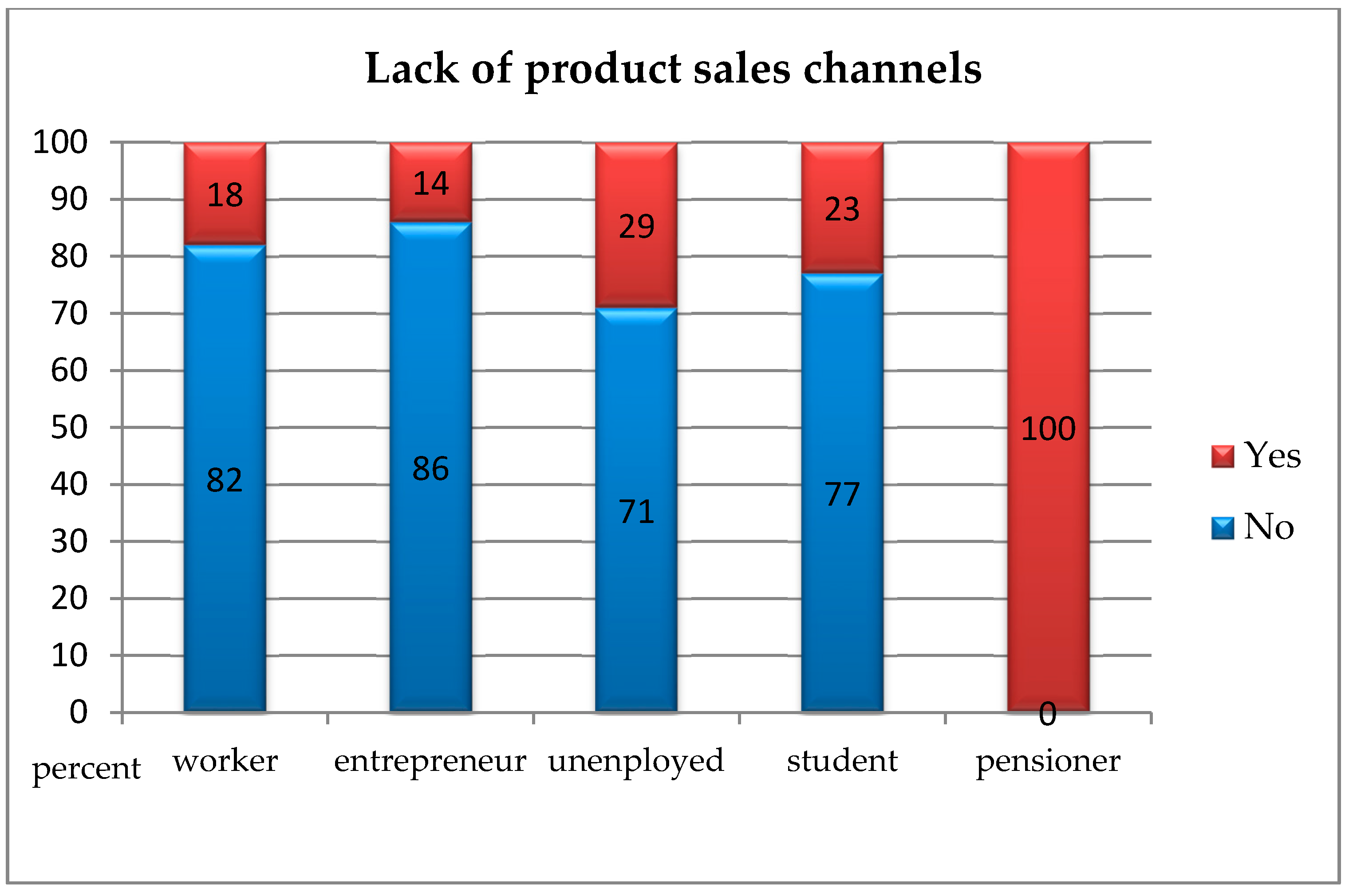

- The absence of sales channels for products: χ2(4, N = 199) = 15.21; p < 0.010; V = 0.31. This means that pensioners more often than manual labourers, entrepreneurs, unemployed, and pupils/students pointed to the absence of sales channels for products as a current problem with the market for environmental goods (Figure 4);

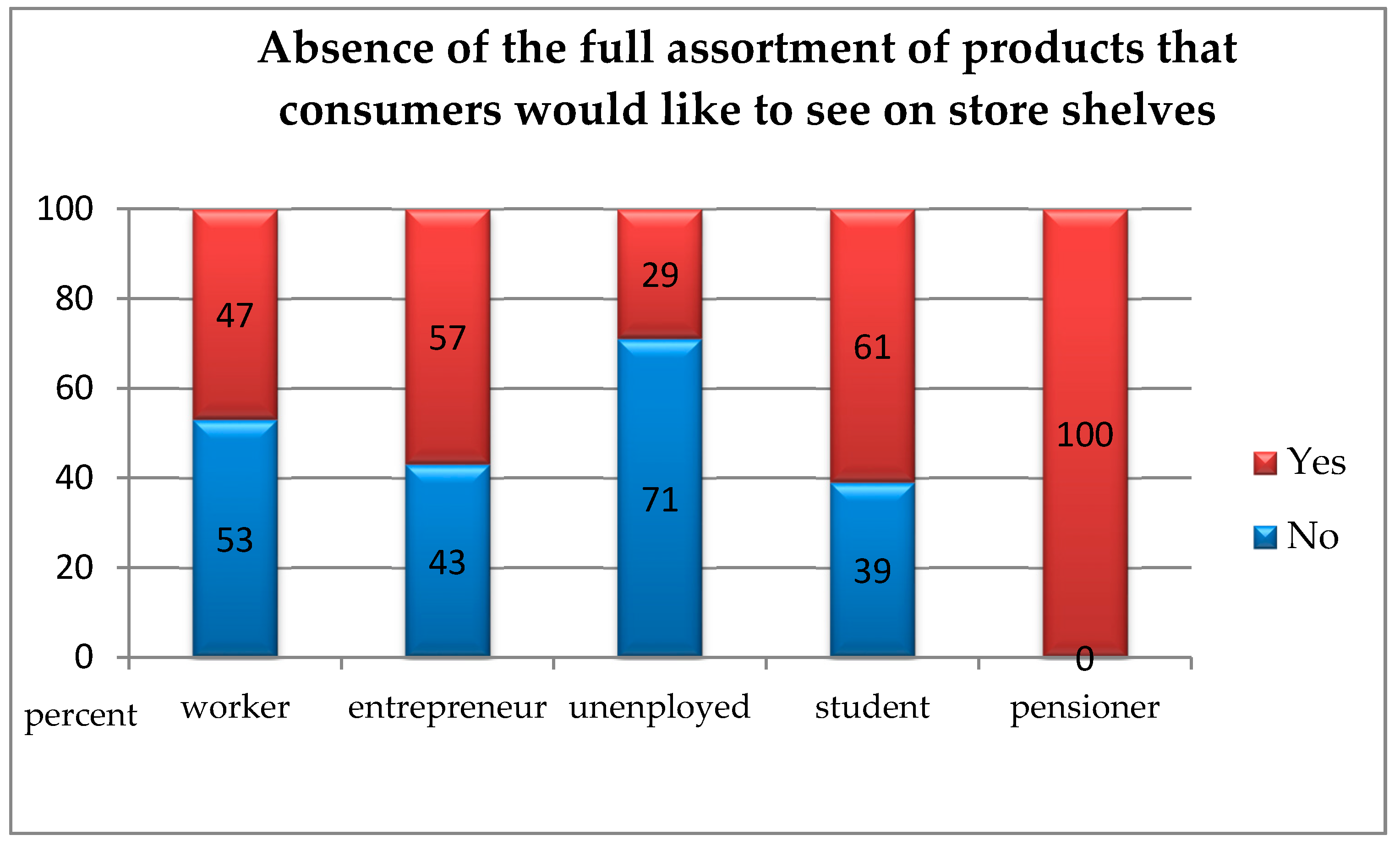

- The absence of the full range of products which consumers would like to see on store shelves: χ2(4, N = 199) = 10.90; p < 0.050; V = 0.24. This means that pensioners more often than manual labourers, entrepreneurs, unemployed, and pupils/students pointed to the absence of sales channels for products as a current problem with the market for environmental goods, whereas the unemployed identified this problem less often than others (Figure 5);

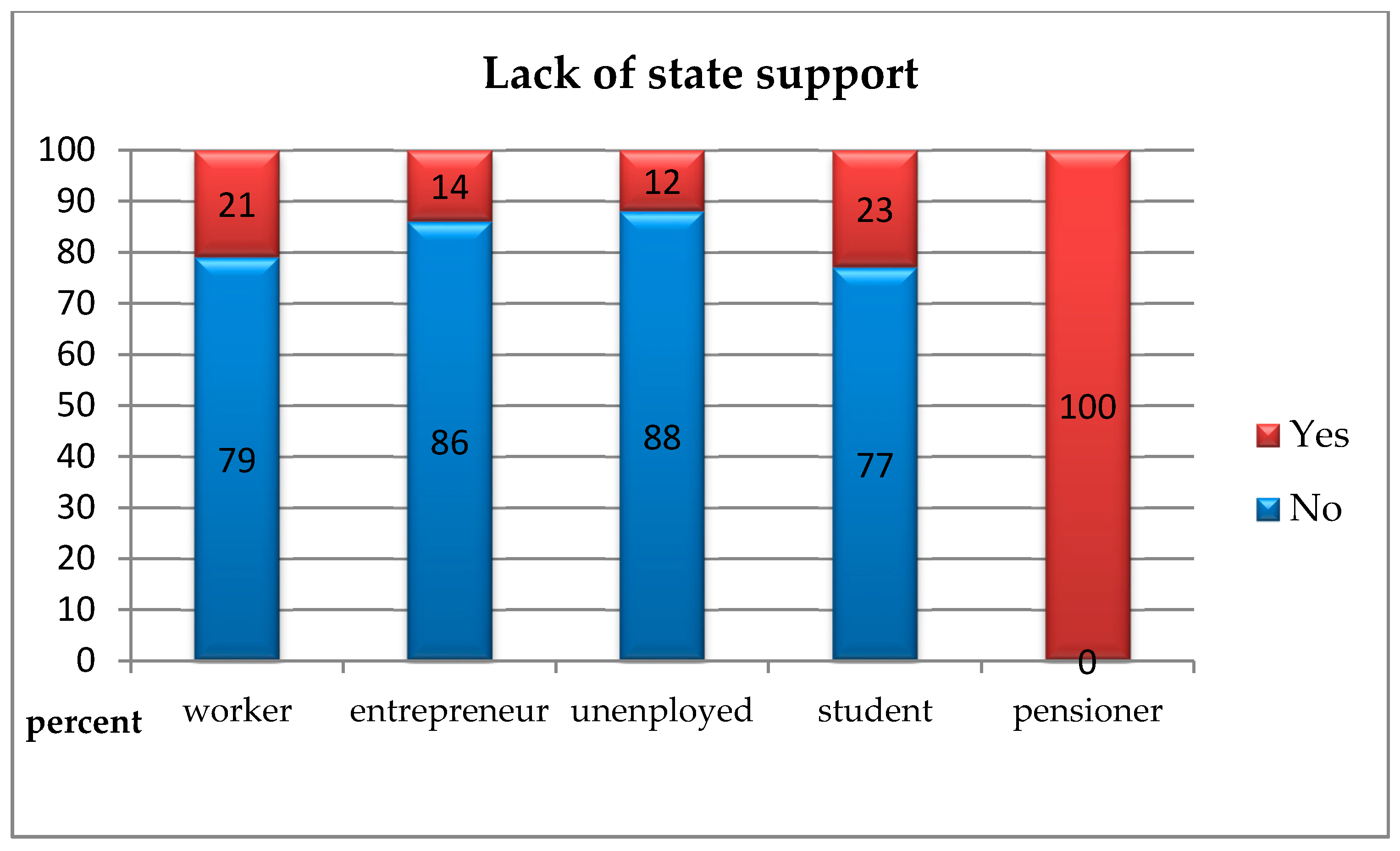

- The absence of state support: χ2(4, N = 199) = 14.52; p < 0.010; V = 0.31. This means that pensioners more often than manual labourers, entrepreneurs, unemployed, and pupils/students pointed to the absence of state support products as a current problem with the market for environmental goods (Figure 6).

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Illiashenko, S.M. Marketing Principles of Implementation Environmental Innovations; Printing House “Papyrus”: Sumy, Ukraine, 2013. (In Ukrainian) [Google Scholar]

- Raszka, B.; Kuras, M. Znajomość Produktów Regionalnych i Tradycyjnych w Wielkopolsce na Przykładzie Powiatu Nowy Tomyśl [Perception of the Regional and Traditional Food-Products in Wielkopolska Region for Instance Nowy Tomysl Dostrict]. Zeszyty Naukowe; Wyższa Szkoła Handlu i Usług w Poznaniu: Poznaniu, Poland, 2010; pp. 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, A. A Study of Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Green Products. J. Adv. Manag. Sci. 2016, 4, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Roy, M. Green products: An exploratory study on the consumer behaviour in emerging economies of the East. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 87, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rex, E.; Baumann, H. Beyond eco-labels: What green marketing can learn from conventional marketing? J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, C.; Shishime, T.; Fujitsuka, T. Sustainable consumption: Green purchasing behaviours of urban residents in China. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 20, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolverton, A.; Dimitri, C. Green marketing: Are environmental and social objectives compatible with profit maximization? Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2010, 25, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru-Jen, L.; Rong-Huei, C.H.; Fei-Hsin, H. Green innovation in the automobile industry. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2014, 114, 886–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muposhi, A.; Dhurup, M. The Influence of Green Marketing Tools on Green Eating Efficacy and Green Eating Behaviour. J. Econ. Behav. Stud. 2017, 9, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świąder, M.; Szewrański, S.Z.; Kazak, J. Foodshed as an example of preliminary research for conducting environmental carrying capacity analysis. Sustainability 2018, 10, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hełdak, M.; Płuciennik, M. Costs of Urbanisation in Poland, Based on the Example of Wrocław. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, Prague, Czech Republic, 12–16 June 2017; Volume 245, p. 72003. Available online: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1757-899X/245/7/072003/meta (accessed on 30 January 2019).

- Solecka, I.; Sylla, M.; Świąder, M. Urban Sprawl Impact on Farmland Conversion in Suburban Area of Wroclaw, Poland. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, Prague, Czech Republic, 12–16 June 2017; Volume 245, p. 72002. Available online: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1757-899X/245/7/072002/meta (accessed on 30 January 2019).

- Stacherzak, A.; Hełdak, M. Borough Development Dependent on Agricultural, Tourism, and Economy Levels. Sustainability 2019, 11, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szewrański, S.; Kazak, J.; Sylla, M.; Świąder, M. Spatial Data Analysis with the Use of ArcGIS and Tableau Systems. In The Rise of Big Spatial Data. Lecture Notes in Geoinformation and Cartography; Ivan, I., Singleton, A., Horák, J., Inspektor, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milovantseva, N. Are American households willing to pay a premium for greening consumption of information and communication technologies? J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 127, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, S.; Lim, S.; Yoo, S. Consumers’ Willingness to Pay a Premium for Eco-Labeled LED TVs in Korea: A Contingent Valuation Study. Sustainability 2017, 9, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leszczynska, A. Willingness to pay for green products vs ecological value system. Int. J. Synerg. Res. 2014, 3, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akeju, T.J.; Adeyinka, S.A.; Oladehinde, G.J.; Fatusin, A.F. Regression analysis of residents’ perception on willingness to pay (WTP) for improved water supply: A case from Nigeria. Agric. Resour. Econ. Int. Sci. E J. 2018, 4, 5–18. Available online: http://www.are-journal.com (accessed on 20 February 2019).

- Badu-Gyan, F.; Owusu, V. Consumer willingness to pay a premium for a functional food in Ghana. Appl. Stud. Agribus. Commer. 2017, 11, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebid, L. Trends in Force: What to Orient Organic Producers. 2018. Available online: http://agroportal.ua/ua/publishing/analitika/trendy-v-sile-na-chto-orientirovatsya-proizvoditelyam-organiki (accessed on 20 February 2019).

- Aichlmayr, M. Eco-Labeling: Green or Smokescreen? Mater. Handl. Manag. 2010, 65, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Gavrilko, P.P. Status and features of development world and national ecological market of goods and services. Sci. Bull. NLTU Ukr. 2012, 22, 68–71. [Google Scholar]

- Miremadi, M.; Musso, C.; Weihe, U. How Much Will Consumers Pay to Go Green? Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/sustainability-and-resource-productivity/our-insights/how-much-will-consumers-pay-to-go-green (accessed on 25 January 2019).

- Consumer Willingness to Pay A Premium for «Green» Products Climbs, Albeit Slowly. Available online: https://www.marketingcharts.com/industries/cpg-and-fmcg-76738 (accessed on 20 January 2019).

- Li, T.; Meshkova, Z. Examining the impact of rich media on consumer willingness to pay in online stores. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2013, 12, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokopenko, O.V.; Alekseienko, O.D. Analysis of the readiness of consumers to pay a price premium for the environmental friendliness of goods of different types. Mech. Regul. Econ. 2006, 2, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Prokopenko, O.V. Ecologization of Innovation Activity: Motivational Approach; Universytetska Knyha: Kharkov, Ukraine, 2008. (In Ukrainian) [Google Scholar]

- Illiashenko, S.M. Eco-friendliness as a factor of product’s competitiveness. Actual Probl. Econ. 2012, 9, 143–150. [Google Scholar]

- Illiashenko, S.M.; Illiashenko, N.S. Motivation is the ecologization of the consumption. In Modern Marketing and Prospects of Development in Ukraine and Its Regions; Seriia «Ekonomika»; zb. nauk. pr. DonDU; 2012; Volume ХIII, pp. 58–69. [Google Scholar]

- Illiashenko, S.M.; Kovalenko, Y.A.; Timoshova, O.Y. Marketing Analysis of the Perception of National Consumers of Ecological Characteristics of Products; Zb. Nauk. pr. Khmelnytskoho Kooperatyvnoho Torhovelno-Ekonomichnoho Instytutu: Khmielnytsko, Ukraine, 2012; Volume 3, pp. 357–364. [Google Scholar]

- Kuchmiyov, A.V. Use of Ecological Marketing Instruments for the Increasing of Region’s Ecological Security Level; Seriia «Ekonomika»; Zb. nauk. pr. Donetskoho Derzhavnoho Universytetu Upravlinnia: Donetsk, Ukraine, 2012; Volume XIII, pp. 182–193. [Google Scholar]

- Kucher, A.V.; Fedorchenko, O.O.; Yurchenko, Y.D. Consumers’ Willingness to Pay a Price Premium for Ecological Goods: Methodology and Results; Kharkov, Ukraine, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, P.W.; Laplante, B.; Maxwell, J. Pollution Policy: The Role for Publicly Provided Information. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 1994, 26, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammer, K.; Wüstenhagen, R. The influence of eco-labelling on consumer behavior—Results of a discrete choice analysis for washing machines. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2006, 15, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumakawa, T. Altruism and Willingness to Pay for Environmental Goods: A Contingent Valuation Study. J. Geosci. Environ. Prot. 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, D.P. Do Children Matter? An Examination of Gender Differences in Environmental Valuation. Ecol. Econ. 2004, 49, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Stern, P.; Guagnano, G. Social Structural and Social Psychological Bases of Environmental Concern. Environ. Behav. 1998, 30, 450–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, F.; Garcia, J.H.; Lofgren, A. Conformity and the Demand for Environmental Goods. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2010, 47, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.; Starr, R. Consumers’ Willingness To Pay (WTP) for Environmentally Friendly Products: Premiums on Low-Priced vs. High-Priced Goods. 2016. Available online: http://econweb.ucsd.edu/~rstarr/191AB%20Fall%202016%20Winter%202017/ExemplaryPapers2016/Consumers%27%20Willingness%20to%20Pay%20for%20Environmentally%20Friendly%20Products.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2019).

- Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Huo, X. Consumer’s Willingness to Pay a Premium for Organic Fruits in China: A Double-Hurdle Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Gao, Z.; Zeng, Y. Willingness to pay for the “green food” in China. Food Policy 2014, 45, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. Consumers’ WTP for certified traceable tea in China. Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 1440–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J. Consumers’ Attitudes, Cognitions and Purchasing Behaviors on Vegetable Safety: Based on Surveys of Urban and Urban Consumers in Zhejiang Province. China Rural Econ. 2010, 11, 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Shen, M.; Gao, Z. Research on the Irrational Behavior of Consumers’ Safe Consumption and Its Influencing Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, W.; Hwang, K.; Mcdonald, S.; Oates, C.J. Sustainable consumption: Green consumer behaviour when purchasing products. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| QUESTIONNAIRE Research on: “The different groups of local consumers’ willingness to pay price premiums for ecological goods” |

| Welcome to you! We invite you to take place in our survey, that we are conducting for revealing local consumers’ willingness to pay price premiums for ecological goods. You will be asked a few questions. Please select an answer that corresponds to your position. This questionnaire is anonymous, the data obtained in a generalized form will be used for scientific and practical purposes |

|

| Thank you for participating in the study! |

| Gender | Number | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 58 | 29.00 |

| Female | 142 | 71.00 |

| Age | Number | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| under 30 | 138 | 69.00 |

| 31–40 | 29 | 14.50 |

| 41–50 | 22 | 11.00 |

| over 50 | 11 | 5.50 |

| Social Status: | Number | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Worker | 99 | 49.50 |

| Official | 1 | 0.50 |

| Entrepreneur | 14 | 7.00 |

| Unemployed | 17 | 8.50 |

| Student | 64 | 32.00 |

| Pensioner | 5 | 2.50 |

| Indicate the Reasons Why You Prefer Ecological Products? | Gender | Together | χ2 | p | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | ||||||||

| n | % From Group | n | % From Group | n | % of Together | ||||

| high-quality goods | No | 11 | 18.97 | 19 | 13.38 | 30 | 15.00 | 1.01 | 0.315 |

| Yes | 47 | 81.03 | 123 | 86.62 | 170 | 85.00 | |||

| Total: | 58 | 100.00 | 142 | 100.00 | 200 | 100.00 | |||

| good for health | No | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | no variability | |

| Yes | 58 | 100.00 | 142 | 10.00 | 200 | 100.00 | |||

| Total: | 58 | 100.00 | 142 | 100.00 | 200 | 100.00 | |||

| safe for the environment | No | 10 | 17.24 | 49 | 34.51 | 59 | 29.50 | 5.90 | 0.015 |

| Yes | 48 | 82.76 | 93 | 65.49 | 141 | 70.50 | |||

| Total: | 58 | 100.00 | 142 | 100.00 | 200 | 100.00 | |||

| it’s fashionable | No | 32 | 55.17 | 97 | 68.31 | 129 | 64.50 | 3.10 | 0.078 |

| Yes | 26 | 44.83 | 45 | 31.69 | 71 | 35.50 | |||

| Total: | 58 | 100.00 | 142 | 100.00 | 200 | 100.00 | |||

| What Do You Pay Attention to When Choosing Environmental Products? | Gender | Together | χ2 | p | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | ||||||||

| n | % From Group | n | % From Group | n | % of Together | ||||

| Producer | No | 49 | 84.48 | 124 | 87.32 | 173 | 86.50 | 0.28 | 0.594 |

| Yes | 9 | 15.52 | 18 | 12.68 | 27 | 13.50 | |||

| Total: | 58 | 100.00 | 142 | 100.00 | 200 | 100.00 | |||

| Price | No | 2 | 3.45 | 23 | 16.20 | 25 | 12.50 | 6.12 | 0.013 |

| Yes | 56 | 96.55 | 119 | 83.80 | 175 | 87.50 | |||

| Total: | 58 | 100.00 | 142 | 100.00 | 200 | 100.00 | |||

| The presence of certification marks | No | 7 | 12.07 | 28 | 19.72 | 35 | 17.50 | 1.67 | 0.196 |

| Yes | 51 | 87.93 | 114 | 80.28 | 165 | 82.50 | |||

| Total: | 58 | 100.00 | 142 | 100.00 | 200 | 100.00 | |||

| Appearance of packaging | No | 36 | 62.07 | 99 | 69.72 | 135 | 67.50 | 1.10 | 0.295 |

| Yes | 22 | 37.93 | 43 | 30.28 | 65 | 32.50 | |||

| Total: | 58 | 100.00 | 142 | 100.00 | 200 | 100.00 | |||

| Taste | No | 14 | 24.14 | 41 | 28.87 | 55 | 27.50 | 0.46 | 0.496 |

| Yes | 44 | 75.86 | 101 | 71.13 | 145 | 72.50 | |||

| Total: | 58 | 100.00 | 142 | 100.00 | 200 | 100.00 | |||

| Storage | No | 13 | 22.41 | 22 | 15.49 | 35 | 17.50 | 1.37 | 0.242 |

| Yes | 45 | 77.59 | 120 | 84.51 | 165 | 82.50 | |||

| Total: | 58 | 100.00 | 142 | 100.00 | 200 | 100.00 | |||

| What Kind of Environmental Products Do You Use? | Age | Total | χ2 | p | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under 30 | 31–40 | 41–50 | Over 50 | ||||||||||

| n | % From Group | n | % From Group | n | % From Group | n | % From Group | n | % of Total | ||||

| Cosmetics | No | 99 | 71.74 | 13 | 44.83 | 17 | 77.7 | 11 | 100.00 | 140 | 70.00 | 13.87 | 0.002 |

| Yes | 39 | 28.26 | 16 | 55.17 | 5 | 22.73 | 0 | 0.00 | 60 | 30.00 | |||

| Total: | 138 | 100.00 | 29 | 100.00 | 22 | 100.00 | 11 | 100.0 | 200 | 100.00 | |||

| Food | No | 15 | 10.87 | 5 | 17.24 | 5 | 22.73 | 0 | 0.00 | 25 | 12.50 | 4.25 | 0.219 |

| Yes | 123 | 89.13 | 24 | 82.76 | 17 | 77.27 | 11 | 100.00 | 175 | 87.50 | |||

| Total: | 138 | 100.00 | 29 | 100.00 | 22 | 100.00 | 11 | 100.00 | 200 | 100.00 | |||

| Clothes | No | 138 | 100.00 | 29 | 100.00 | 22 | 100.00 | 11 | 100.00 | 200 | 100.00 | no variability | |

| Yes | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | |||

| Total: | 138 | 100.00 | 29 | 100.00 | 22 | 100.00 | 11 | 100.00 | 200 | 100.00 | |||

| Furniture | No | 138 | 100.00 | 29 | 100.00 | 22 | 100.00 | 11 | 100.00 | 200 | 100.00 | no variability | |

| Yes | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | |||

| Total: | 138 | 100.00 | 29 | 100.00 | 22 | 100.00 | 11 | 100.00 | 200 | 100.00 | |||

| Packets and bags | No | 107 | 77.54 | 14 | 48.28 | 18 | 81.82 | 11 | 100.00 | 150 | 75.00 | 14.36 | 0.002 |

| Yes | 31 | 22.46 | 15 | 51.72 | 4 | 18.18 | 0 | 0.00 | 50 | 25.00 | |||

| Total: | 138 | 100.00 | 29 | 100.00 | 22 | 100.00 | 11 | 100.00 | 200 | 100.00 | |||

| Supplements | No | 127 | 92.03 | 25 | 86.21 | 22 | 100.00 | 11 | 100.00 | 185 | 92.50 | 3.35 | 0.292 |

| Yes | 11 | 7.97 | 4 | 13.79 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 15 | 7.50 | |||

| Total: | 138 | 100.00 | 29 | 100.00 | 22 | 100.00 | 11 | 100.00 | 200 | 100.00 | |||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kucher, A.; Hełdak, M.; Kucher, L.; Raszka, B. Factors Forming the Consumers’ Willingness to Pay a Price Premium for Ecological Goods in Ukraine. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 859. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16050859

Kucher A, Hełdak M, Kucher L, Raszka B. Factors Forming the Consumers’ Willingness to Pay a Price Premium for Ecological Goods in Ukraine. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(5):859. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16050859

Chicago/Turabian StyleKucher, Anatolii, Maria Hełdak, Lesia Kucher, and Beata Raszka. 2019. "Factors Forming the Consumers’ Willingness to Pay a Price Premium for Ecological Goods in Ukraine" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 5: 859. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16050859

APA StyleKucher, A., Hełdak, M., Kucher, L., & Raszka, B. (2019). Factors Forming the Consumers’ Willingness to Pay a Price Premium for Ecological Goods in Ukraine. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(5), 859. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16050859