Assessing the Relation between Plasma PCB Concentrations and Elevated Autistic Behaviours using Bayesian Predictive Odds Ratios

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Maternal-Infant Research on Environmental Chemicals (MIREC) Study

2.2. Biomarkers of PCB Exposure

2.3. Social Responsiveness Scale Score

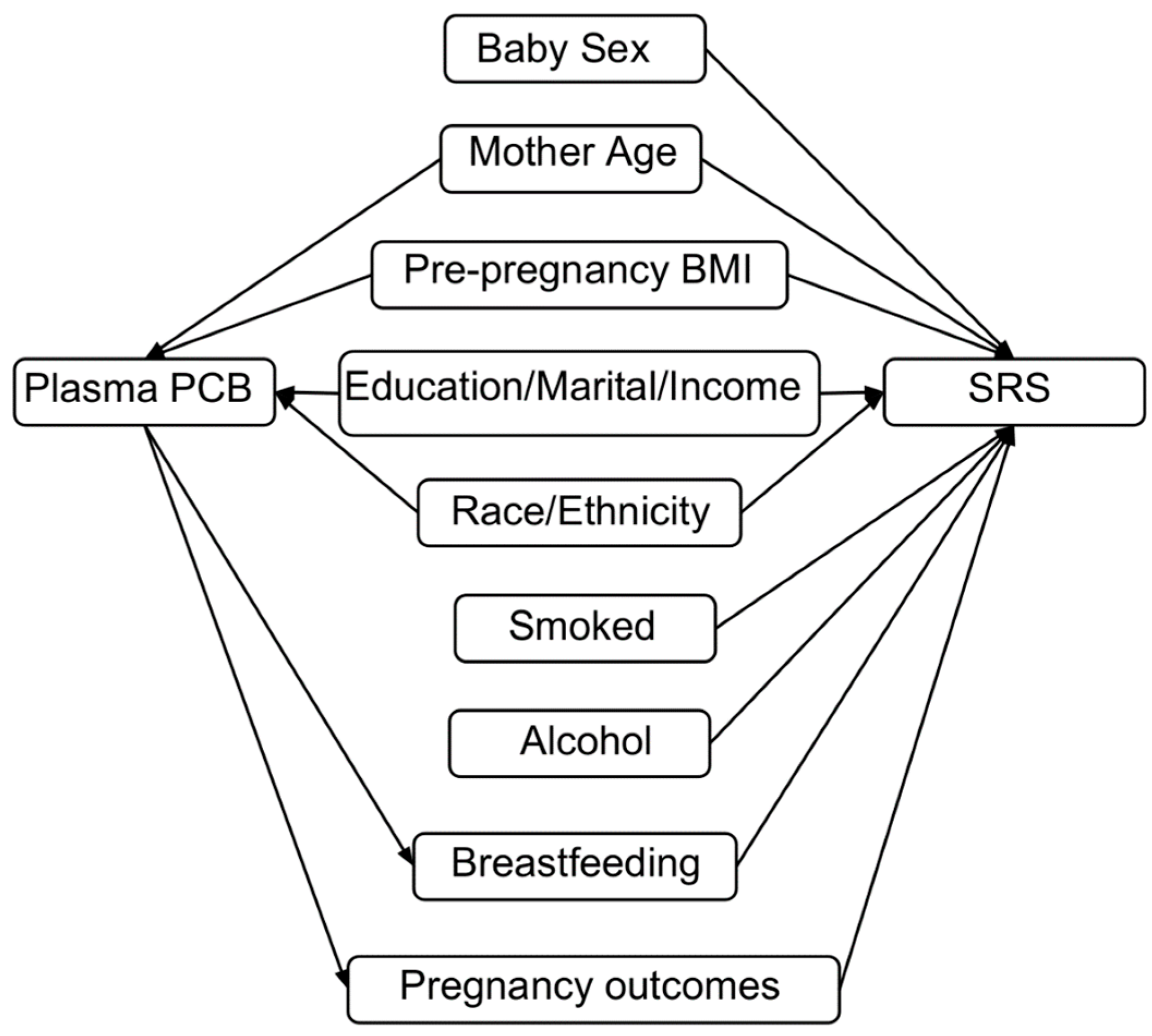

2.4. Covariates

2.5. Analytic Approach

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Linear Regression Analyses

3.3. BPOR Analyses

3.4. Supplemental Analyses of SRS Subscales and Stratification by Sex

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Disclosure

References

- Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network Surveillance Year 2008 Principal Investigators, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 14 sites, United States, 2008. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2012, 61, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kalkbrenner, A.E.; Schmidt, R.J.; Penlesky, A.C. Environmental Chemical Exposures and Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Review of the Epidemiological Evidence. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 2014, 44, 277–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyall, K.; Schmidt, R.J.; Hertz-Picciotto, I. Maternal lifestyle and environmental risk factors for autism spectrum disorders. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 43, 443–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ornoy, A.; Weinstein-Fudim, L.; Ergaz, Z. Prenatal factors associated with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Reprod. Toxicol. 2015, 56, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbert, M.R. Contributions of the environment and environmentally vulnerable physiology to autism spectrum disorders. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2010, 23, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Cock, M.; Maas, Y.G.H.; van de Bor, M. Does perinatal exposure to endocrine disruptors induce autism spectrum and attention deficit hyperactivity disorders? Rev. Acta Paediatr. 2012, 101, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsabbagh, M.; Divan, G.; Koh, Y.J.; Kim, Y.S.; Kauchali, S.; Marcín, C.; Montiel-Nava, C.; Patel, V.; Paula, C.S.; Wang, C.; et al. Global prevalence of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Autism Res. 2012, 5, 160–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyall, K.; Croen, L.; Daniels, J.; Fallin, M.D.; Ladd-Acosta, C.; Lee, B.K.; Park, B.Y.; Snyder, N.W.; Schendel, D.; Volk, H.; et al. The Changing Epidemiology of Autism Spectrum Disorders. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2017, 38, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adetona, O.; Horton, K.; Sjodin, A.; Jones, R.; Hall, D.B.; Aguillar-Villalobos, M.; Cassidy, B.E.; Vena, J.E.; Needham, L.L.; Naeher, L.P. Concentrations of select persistent organic pollutants across pregnancy trimesters in maternal and in cord serum in Trujillo, Peru. Chemosphere 2013, 91, 1426–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roelens, S.A.; Beck, V.; Aerts, G.; Clerens, S.; Vanden Bergh, G.; Arckens, L.; Darras, V.M.; Van der Geyten, S. Neurotoxicity of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) by disturbance of thyroid hormone-regulated genes. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2005, 1040, 454–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs). Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/chemical-substances/fact-sheets/chemicals-glance/polychlorinated-biphenyls.html (accessed on 19 September 2018).

- Warmuth, A.; Ohno, K. The PCBs elimination Network: The Information Exchange Platform Created for the Risk Reduction of Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs). Available online: http://chm.pops.int/Implementation/IndustrialPOPs/PCBs/PCBEliminationNetwork/PENOverview/Relatedarticlesandlinks/PCBsInfoexchangeplatform/tabid/3016/Default.aspx (accessed on 31 January 2019).

- Breivik, K.; Alcock, R.; Li, Y.-F.; Bailey, R.E.; Fiedler, H.; Pacyna, J.M. Primary sources of selected POPs: Regional and global scale emission inventories. Environ. Pollut. 2004, 128, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowack, N.; Wittsiepe, J.; Kasper-Sonnenberg, M.; Wilhelm, M.; Schölmerich, A. Influence of Low-Level Prenatal Exposure to PCDD/Fs and PCBs on Empathizing, Systemizing and Autistic Traits: Results from the Duisburg Birth Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashwood, P.; Schauer, J.; Pessah, I.N.; Van de Water, J. Preliminary evidence of the in vitro effects of BDE-47 on innate immune responses in children with autism spectrum disorders. J. Neuroimmunol. 2009, 208, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura-Kuroda, J.; Nagata, I.; Kuroda, Y. Disrupting effects of hydroxy-polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) congeners on neuronal development of cerebellar Purkinje cells: A possible causal factor for developmental brain disorders? Chemosphere 2007, 67, S412–S420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shelton, J.F.; Hertz-Picciotto, I.; Pessah, I.N. Tipping the balance of autism risk: Potential mechanisms linking pesticides and autism. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012, 120, 944–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, J.L.; Jacobson, S.W. Intellectual impairment in children exposed to polychlorinated biphenyls in utero. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 335, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossignol, D.A.; Genuis, S.J.; Frye, R.E. Environmental toxicants and autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Transl. Psychiatry 2014, 4, e360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheslack-Postava, K.; Rantakokko, P.V.; Hinkka-Yli-Salomäki, S.; Surcel, H.M.; McKeague, I.W.; Kiviranta, H.A.; Sourander, A.; Brown, A.S. Maternal serum persistent organic pollutants in the Finnish Prenatal Study of Autism: A pilot study. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2013, 38, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyall, K.; Croen, L.A.; Sjödin, A.; Yoshida, C.K.; Zerbo, O.; Kharrazi, M.; Windham, G.C. Polychlorinated Biphenyl and Organochlorine Pesticide Concentrations in Maternal Mid-Pregnancy Serum Samples: Association with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Intellectual Disability. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, J.M.; Muckle, G.; Arbuckle, T.; Bouchard, M.F.; Fraser, W.D.; Ouellet, E.; Séguin, J.R.; Oulhote, Y.; Webster, G.M.; Lanphear, B.P. Associations of Prenatal Urinary Bisphenol A Concentrations with Child Behaviors and Cognitive Abilities. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125, 067008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.S.; Cheslack-Postava, K.; Rantakokko, P.; Kiviranta, H.; Hinkka-Yli-Salomäki, S.; McKeague, I.W.; Surcel, H.M.; Sourander, A. Association of Maternal Insecticide Levels with Autism in Offspring from a National Birth Cohort. Am. J. Psychiatry 2018, 175, 1094–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelman, A.; Weakliem, D. Of Beauty, Sex and Power: Too little attention has been paid to the statistical challenges in estimating small effects. Am. Sci. 2009, 97, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelman, A.; Hill, J. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevelhierarchical Models. lac.essex.ac.uk. 2007. Available online: http://lac.essex.ac.uk/local--files/meetings1213/gelman_1.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2019).

- Canadian Environmental Health Atlas. Little Things Matter: The Impact of Toxins on the Developing Brain [Internet]. Youtube. 2014. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E6KoMAbz1Bw (accessed on 31 January 2019).

- Arbuckle, T.E.; Fraser, W.D.; Fisher, M.; Davis, K.; Liang, C.L.; Lupien, N.; Bastien, S.; Velez, M.P.; von Dadelszen, P.; Hemmings, D.G.; et al. Cohort profile: The maternal-infant research on environmental chemicals research platform. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2013, 27, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, M.; Arbuckle, T.E.; Liang, C.L.; LeBlanc, A.; Gaudreau, E.; Foster, W.G.; Haines, D.; Davis, K.; Fraser, W.D. Concentrations of persistent organic pollutants in maternal and cord blood from the maternal-infant research on environmental chemicals (MIREC) cohort study. Environ. Health 2016, 15, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubin, J.H.; Colt, J.S.; Camann, D.; Davis, S.; Cerhan, J.R.; Severson, R.K.; Bernstein, L.; Hartge, P. Epidemiologic evaluation of measurement data in the presence of detection limits. Environ. Health Perspect. 2004, 112, 1691–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axelrad, D.A.; Goodman, S.; Woodruff, T.J. PCB body burdens in US women of childbearing age 2001–2002: An evaluation of alternate summary metrics of NHANES data. Environ. Res. 2009, 109, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, K.M.; Upson, K.; Cook, N.R.; Weinberg, C.R. Environmental Chemicals in Urine and Blood: Improving Methods for Creatinine and Lipid Adjustment. Environ. Health Perspect. 2016, 124, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schisterman, E.F.; Whitcomb, B.W.; Louis, G.M.B.; Louis, T.A. Lipid adjustment in the analysis of environmental contaminants and human health risks. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005, 113, 853–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (SRSTM-2) Social Responsiveness ScaleTM, Second Edition|WPS. Available online: https://www.wpspublish.com/store/p/2994/srs-2-social-responsiveness-scale-second-edition (accessed on 30 January 2018).

- Bolte, S.; Poustka, F.; Constantino, J.N. Assessing Autistic Traits: Cross-Cultural Validation of the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS). Autism Res. 2008, 1, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, K.A.; Park, J.I.; Koh, Y.J.; Song, J.; Hong, H.J.; Kim, Y.K.; Lim, E.C.; Kwon, H.; Ha, M.; Lim, M.H.; et al. The social responsiveness scale in relation to DSM IV and DSM5 ASD in Korean children. Autism Res. 2016, 9, 970–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, T.W.; Youngstrom, E.A.; Hardan, A.Y.; Georgiades, S.; Constantino, J.N.; Eng, C. Quantitative autism symptom patterns recapitulate differential mechanisms of genetic transmission in single and multiple incidence families. Mol. Autism 2015, 6, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constantino, J.N.; Todd, R.D. Intergenerational transmission of subthreshold autistic traits in the general population. Biol. Psychiatry 2005, 57, 655–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernán, M.A.; Hernández-Díaz, S.; Werler, M.M.; Mitchell, A.A. Causal knowledge as a prerequisite for confounding evaluation: An application to birth defects epidemiology. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2002, 155, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weldon, R.H.; Webster, M.; Harley, K.; Bradman, A.; Fenster, L.; Barr, D.B.; Jewell, N.P.; Holland, N.; Eskenazi, B. Exposure to Persistent Organic Pollutants and Duration of Lactation in Mexican-American Mothers. Epidemiology 2006, 17, S193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govarts, E.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.; Schoeters, G.; Ballester, F.; Bloemen, K.; De Boer, M.; Chevrier, C.; Eggesbø, M.; Guxens, M.; Krämer, U.; et al. Birth weight and prenatal exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (DDE): A meta-analysis within 12 European Birth Cohorts. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012, 120, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desrochers-Couture, M.; Oulhote, Y.; Arbuckle, T.E.; Fraser, W.D.; Séguin, J.R.; Ouellet, E.; Forget-Dubois, N.; Ayotte, P.; Boivin, M.; Lanphear, B.P.; et al. Prenatal, concurrent, and sex-specific associations between blood lead concentrations and IQ in preschool Canadian children. Environ. Int. 2018, 121, 1235–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flegal, K.M.; Keyl, P.M.; Nieto, F.J. Differential misclassification arising from nondifferential errors in exposure measurement. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1991, 134, 1233–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denison, D.G.T.; Holmes, C.C.; Mallick, B.K.; Smith, A.F.M. Bayesian Methods for Nonlinear Classification and Regression; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, B.; Gelman, A.; Hoffman, M.D.; Lee, D.; Goodrich, B.; Betancourt, M.; Brubaker, M.; Guo, J.; Li, P.; Riddell, A. Stan: A Probabilistic Programming Language. J. Stat. Softw. 2017, 76, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunson, D.B. Commentary: Practical advantages of Bayesian analysis of epidemiologic data. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2001, 153, 1222–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, M.; Hatton, D. Distinguishing features of autism in boys with fragile X syndrome. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2010, 54, 894–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, M.; Miller, M.; Taylor, S.L.; Hinshaw, S.P.; Carter, C.S. Autism symptoms and internalizing psychopathology in girls and boys with autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2012, 42, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartley, S.L.; Sikora, D.M. Sex differences in autism spectrum disorder: An examination of developmental functioning, autistic symptoms, and coexisting behavior problems in toddlers. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2009, 39, 1715–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haines, D.A.; Saravanabhavan, G.; Werry, K.; Khoury, C. An overview of human biomonitoring of environmental chemicals in the Canadian Health Measures Survey: 2007–2019. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2017, 220, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Report on Human Biomonitoring of Environmental Chemicals in Canada: Results of the Canadian Health Measures Survey Cycle 1 (2007–2009) Ottawa: Health Canada. Health Canada, 2010. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/migration/hc-sc/ewh-semt/alt_formats/hecs-sesc/pdf/pubs/contaminants/chms-ecms/report-rapport-eng.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2019).

- Woodruff, T.J.; Zota, A.R.; Schwartz, J.M. Environmental Chemicals in Pregnant Women in the United States: NHANES 2003–2004. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011, 119, 878–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albert, J.H.; Chib, S. Bayesian Analysis of Binary and Polychotomous Response Data. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1993, 88, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needleman, H.L.; Bellinger, D. The health effects of low level exposure to lead. Annu. Rev. Public Health 1991, 12, 111–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Needleman, H.L.; Bellinger, D. Prenatal Exposure to Toxicants; Johns Hopkins Univ. Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bellinger, D.; Leviton, A.; Waternaux, C.; Needleman, H.; Rabinowitz, M. Longitudinal analyses of prenatal and postnatal lead exposure and early cognitive development. N. Engl. J. Med. 1987, 316, 1037–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korrick, S.A.; Sagiv, S.K. Polychlorinated biphenyls, organochlorine pesticides and neurodevelopment. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2008, 20, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longnecker, M.P.; Wolff, M.S.; Gladen, B.C.; Brock, J.W.; Grandjean, P.; Jacobson, J.L.; Korrick, S.A.; Rogan, W.J.; Weisglas-Kuperus, N.; Hertz-Picciotto, I.; et al. Comparison of Polychlorinated Biphenyl Levels across Studies of Human Neurodevelopment. Environ. Health Perspect. 2002, 111, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vocht, F.; Cherry, N.; Wakefield, J. A Bayesian mixture modeling approach for assessing the effects of correlated exposures in case-control studies. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2012, 22, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobb, J.F.; Valeri, L.; Claus Henn, B.; Christiani, D.C.; Wright, R.O.; Mazumdar, M.; Godleski, J.J.; Coull, B.A. Bayesian kernel machine regression for estimating the health effects of multi-pollutant mixtures. Biostatistics 2015, 16, 493–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herring, A.H. Nonparametric bayes shrinkage for assessing exposures to mixtures subject to limits of detection. Epidemiology 2010, 21 (Suppl. 4), S71–S76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLehose, R.F.; Dunson, D.B.; Herring, A.H.; Hoppin, J.A. Bayesian methods for highly correlated exposure data. Epidemiology 2007, 18, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hus, V.; Bishop, S.; Gotham, K.; Huerta, M.; Lord, C. Factors influencing scores on the social responsiveness scale. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2013, 54, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiersen, A.M.; Constantino, J.N.; Volk, H.E.; Todd, R.D. Autistic traits in a population-based ADHD twin sample. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2007, 48, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, E.J.H.; Venema, K.; Earl, R.K.; Lowy, R.; Webb, S.J. Infant social attention: An endophenotype of ASD-related traits? J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2017, 58, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PCB Category 1 | Value (ng/g Lipid) | n | SRS Unadjusted Mean Scores (95% CI) | SRS Adjusted 2 Mean Scores (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCB118 | ||||

| Q1 | <1.4 | 108 | 0.0 (referent) | 0.0 |

| Q2 | 1.4 -< 2.3 | 143 | −0.03 (−1.49, 1.50) | 0.09 (−1.46, 1.63) |

| Q3 | 2.3 -< 3.6 | 170 | −0.49 (−1.90, 0.98) | −0.02 (−1.55, 1.53) |

| Q4 | ≥3.6 | 125 | −0.36 (−1.89, 1.20) | 0.26 (−1.34, 1.88) |

| PCB138 | ||||

| Q1 | < 3.2 | 175 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Q2 | 3.2-< 5.5 | 184 | 0.10 (−1.13, 1.32) | 0.70 (−0.63, 2.04) |

| Q3 | 5.5-< 8.9 | 118 | −0.21 (−1.59, 1.18) | 0.44 (−1.11, 2.01) |

| Q4 | ≥ 8.9 | 69 | 0.52 (−1.15, 2.19) | 1.35 (−0.42, 3.16) |

| PCB153 | ||||

| Q1 | < 4.2 | 87 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Q2 | 4.2-< 7.4 | 178 | 0.41 (−1.14, 1.95) | 0.58 (−1.02, 2.19) |

| Q3 | 7.4-< 11.7 | 144 | −1.08 (−2.70, 0.50) | −0.50 (−2.25, 1.26) |

| Q4 | ≥ 11.7 | 137 | 0.16 (−1.46, 1.76) | 1.10 (−0.71, 2.89) |

| PCB170 | ||||

| Q1 | < 1.5 | 227 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Q2 | 1.5-< 2.6 | 141 | −0.79 (−2.04, 0.48) | −0.33 (−1.66, 1.02) |

| Q3 | 2.6-< 4.3 | 110 | −1.12 (−2.49, 0.24) | −0.14 (−1.64, 1.33) |

| Q4 | ≥ 4.3 | 68 | 0.02 (−1.58, 1.64) | 0.83 (−0.97, 2.62) |

| PCB180 | ||||

| Q1 | < 3.4 | 154 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Q2 | 3.4-< 6.1 | 182 | −1.99 (−3.25, −0.72) | −1.57 (−2.93, −0.16) |

| Q3 | 6.1-< 10.4 | 120 | −2.00 (−3.41, −0.58) | −1.13 (−2.75, 0.50) |

| Q4 | >= 10.4 | 90 | −0.48 (−2.02, 1.05) | 0.19 (−1.60, 1.97) |

| PCB187 | ||||

| Q1 | < 0.92 | 197 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Q2 | 0.92-< 1.8 | 124 | −0.30 (−1.64, 1.04) | −0.49 (−1.83, 0.88) |

| Q3 | 1.8-< 3.3 | 135 | −0.86 (−2.15, 0.44) | −0.46 (−1.84, 0.94) |

| Q4 | >= 3.3 | 90 | −0.20 (−1.71, 1.27) | 0.51 (−1.15, 2.15) |

| Sum of above PCBs | ||||

| Q1 | < 33.4 | 358 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Q2 | 33.4-< 55.3 | 110 | −0.29 (−1.58, 0.98) | 0.60 (−0.75, 1.96) |

| Q3 | 55.3-< 86.3 | 51 | 0.16 (−1.59, 1.93) | 0.67 (−1.21, 2.53) |

| Q4 | ≥ 86.3 | 27 | 0.73 (−1.66, 3.12) | 1.45 (−0.98, 3.90) |

| MIREC | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Congener | %>LOD CHMS 1 | %>LOD MIREC | GM 2 CHMS 1 | GM MIREC | Mean MIREC | SD | 25th | 50th | 75th | 95th | Max |

| PCB118 | 83.2 | 77.5 | 3.09 | 2.1 | 2.9 | 2.6 | 1.7 | 2.4 | 3.4 | 6.9 | 30.2 |

| PCB138 | 96.1 | 95.2 | 5.46 | 4.3 | 5.6 | 5.2 | 2.9 | 4.2 | 6.2 | 14.4 | 46.8 |

| PCB153 | 91.6 | 100 | 8.22 | 7.9 | 10.1 | 9.7 | 4.9 | 7.5 | 11.7 | 25.0 | 80.9 |

| PCB170 | 50.2 | 56.8 | NA | 1.4 | 2.6 | 3.5 | 0.7 | 1.9 | 3.1 | 7.2 | 40.3 |

| PCB180 | 95.4 | 97.1 | 5.79 | 5.3 | 7.5 | 9.3 | 3.2 | 5.1 | 8.2 | 19.6 | 114.9 |

| PCB187 | 41.1 | 46.0 | NA | 1.2 | 2.0 | 2.4 | 0.6 | 1.4 | 2.5 | 5.5 | 26.9 |

| Sum of PCBs 3 | NA | NA | NA | 26.7 | 34.9 | 34.9 | 16.5 | 25.3 | 40.9 | 81.9 | 345.3 |

| n (%) | SRS (Median (IQR)) | PCB118 | PCB138 | PCB153 | PCB170 | PCB180 | PCB187 | Sum of PCBs 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (ng/g Lipid) (Median (IQR)) | |||||||||

| Total | 546 (100) | 44 (41–49) | 2.4 (1.7–3.4) | 4.2 (2.9–6.2) | 7.5 (4.9–11.7) | 1.9 (0.7–3.1) | 5.1 (3.2–8.2) | 1.4 (0.6–2.5) | 25.3 (16.5–40.9) |

| Child Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 261 (47.8) | 45 (42–50) | 2.5 (1.7–3.4) | 4.3 (3–6.3) | 7.6 (5–11.4) | 1.8 (0.7–3) | 5.1 (3.2–7.9) | 1.4 (0.6–2.5) | 26.5 (16.9–38.9) |

| Female | 285 (52.2) | 43 (40–47) | 2.4 (1.6–3.4) | 4.2 (2.8–6.2) | 7.3 (4.8–11.8) | 1.9 (0.7–3.1) | 5.2 (3.2–8.4) | 1.4 (0.6–2.5) | 24.5 (15.5–41.6) |

| Mother’s Age | |||||||||

| 19–29 | 122 (22.3) | 45 (42–52) | 1.9 (1.2–2.6) | 3 (2.2–4) | 5 (3.6–7.4) | 1 (0.4–1.9) | 3.1 (2.2–5.1) | 1 (0.5–1.6) | 16.7 (12.2–24.4) |

| 30–34 | 205 (37.5) | 44 (41–48) | 2.3 (1.7–3.3) | 4.2 (2.9–5.8) | 7.2 (4.9–10.4) | 1.5 (0.6–2.7) | 4.8 (3.2–7.2) | 1.2 (0.5–2.1) | 24.1 (16.6–35.1) |

| 35+ | 219 (40.0) | 44 (40–47) | 2.8 (2.1–4.2) | 5.5 (3.6–7.8) | 9.6 (6.7–14.3) | 2.4 (1.6–3.8) | 6.7 (4.8–10.3) | 2.1 (1–3.3) | 33 (23.5–49.5) |

| Race | |||||||||

| White | 491 (89.9) | 44 (40–49) | 2.9 (2.4–4.8) | 5.8 (3.7–9.1) | 11.6 (7.1–18) | 2.6 (1.9–5.4) | 7.1 (5.1–12.7) | 2.9 (1.2–3.8) | 40.2 (25.9–57.6) |

| Other | 55 (10.1) | 44 (40–49) | 2.9 (2.4–3.4) | 6 (4.1–9.2) | 13 (8.2–18) | 3.5 (2–5.6) | 9.8 (5.2–14) | 3.1 (1.2–6.3) | 46.5 (28.9–76.4) |

| Marital Status | |||||||||

| Married | 241 (89.9) | 44 (40–49) | 2.9 (2.4–4.8) | 5.8 (3.7–9.1) | 11.6 (7.1–18) | 2.6 (1.9–5.4) | 7.1 (5.1–12.7) | 2.9 (1.2–3.8) | 40.2 (25.9–57.6) |

| Other | 154 (28.2) | 44 (40–49) | 2.9 (2.4–4) | 5.3 (3.7–9.2) | 9.1 (6.9–18.2) | 2.6 (1.9–5.5) | 7 (5.1–13.2) | 2 (1–5.7) | 30.7 (25.9–70) |

| Education Level | |||||||||

| High School Diploma or less | 29 (5.3) | 44.5 (42–52.2) | 1.4 (0.5–2.2) | 2.6 (1.9–3.5) | 4.6 (3.5–6.1) | 0.7 (0.3–1.7) | 3.1 (1.9–4.5) | 0.6 (0.2–1) | 14.5 (12.2–19.5) |

| College or Trade School Diploma | 154 (28.2) | 45 (42–50) | 2.2 (1.5–3.1) | 3.6 (2.5–5.8) | 6 (4.2–9.9) | 1.3 (0.4–2.5) | 4 (2.6–6.7) | 1.2 (0.5–2.3) | 19.5 (14.1–33.8) |

| Undergraduate University Degree | 213 (39.0) | 45 (41–49) | 2.4 (1.8–3.4) | 4.4 (3–6.2) | 7.5 (5–11.2) | 1.8 (0.8–3) | 5.1 (3.4–7.6) | 1.4 (0.6–2.3) | 24.9 (16.9–39) |

| Graduate University Degree | 150 (27.5) | 43 (40–47) | 2.9 (2.1–3.9) | 5.1 (3.6–7.3) | 9.6 (6.9–13.2) | 2.5 (1.6–3.6) | 6.8 (4.8–9.9) | 2 (1–3.3) | 33.4 (23.7–47.9) |

| Annual Household Income | |||||||||

| ≤$40,000 | 73 (13.4) | 45 (42.8–52.2) | 2.2 (1.5–3.1) | 3.4 (2.4–5.8) | 6.3 (3.7–11.2) | 1.5 (0.6–2.8) | 4.5 (2.3–7.4) | 1 (0.4–2.3) | 20.1 (12.8–39.1) |

| $40,001–$80,000 | 151 (27.7) | 45 (41.5–50.5) | 2.3 (1.7–3.5) | 3.8 (2.7–6) | 6.9 (4.5–10.5) | 1.5 (0.5–2.7) | 4.7 (2.9–7.2) | 1.4 (0.8–2.4) | 23.5 (14.9–36.2) |

| $80,001–$100,000 | 105 (19.2) | 44.5 (40.8–49) | 2.1 (1.2–3.1) | 3.7 (2.7–5.9) | 6.2 (4.6–10.7) | 1.5 (0.7–2.7) | 4.2 (3.2–7.6) | 1.1 (0.4–1.9) | 19.9 (14.8–36.6) |

| >$100,000 | 217 (39.7) | 44 (40–47) | 2.6 (1.9–3.9) | 4.9 (3.5–6.8) | 8.6 (5.9–12.5) | 2.1 (1.2–3.5) | 6 (4.1–9.6) | 1.8 (0.7–2.9) | 29.4 (19.5–44.6) |

| Has Ever Smoked During Pregnancy | |||||||||

| Yes | 189 (34.6) | 45 (40–49) | 2.4 (1.6–3.4) | 4.6 (2.9–6.4) | 7.8 (5.2–12.5) | 2 (0.8–3.4) | 5.3 (3.3–8.9) | 1.6 (0.6–2.7) | 27 (17–42.4) |

| No | 357 (65.4) | 44 (41–48) | 2.4 (1.7–3.4) | 4.2 (2.9–6.1) | 7.4 (4.9–11.3) | 1.8 (0.7–3) | 5.1 (3.2–8) | 1.3 (0.6–2.4) | 24.9 (16–38.6) |

| Has Ever Consumed Alcohol During Pregnancy | |||||||||

| Yes | 91 (16.7) | 44 (40–48) | 2.7 (2.1–3.8) | 4.5 (3.4–6.6) | 7.6 (5.5–12.4) | 2 (0.6–3.3) | 5.3 (3.6–8.7) | 1.4 (0.5–2.5) | 26.5 (18.7–44.3) |

| No | 455 (83.3) | 44 (41–49) | 2.4 (1.6–3.4) | 4.2 (2.8–6.2) | 7.4 (4.8–11.5) | 1.8 (0.7–3) | 5.1 (3.1–8.1) | 1.4 (0.6–2.5) | 25.2 (15.9–40.1) |

| Pre-Pregnancy BMI | |||||||||

| Underweight | 14 (2.6) | 46.5 (42–48.8) | 2.5 (0.5–3.3) | 5.6 (2.4–8.3) | 11.2 (4.4–19.3) | 2.7 (1.1–4.1) | 7.9 (3.6–10.9) | 2.4 (1.2–3.9) | 39.5 (15–61.2) |

| Normal | 332 (60.8) | 44 (41–49) | 2.5 (1.6–3.6) | 4.6 (3.1–6.4) | 8.1 (5.6–12.3) | 2.1 (1.1–3.3) | 5.7 (4–9.1) | 1.7 (0.7–2.7) | 27.3 (18.2–42.5) |

| Overweight | 112 (20.5) | 44 (41–48) | 2.5 (1.6–3.4) | 4.3 (2.9–6.4) | 7.4 (4.5–11.8) | 1.6 (0.7–2.9) | 4.7 (3–7.8) | 1.2 (0.5–2.5) | 24.9(14.7–41.5) |

| Obese | 88 (16.1) | 44 (41–51) | 2.2 (1.7–2.9) | 3 (2.4–4.7) | 5.2 (3.8–8) | 0.8 (0.3–1.8) | 3 (2.2–4.8) | 1 (0.3–1.6) | 17 (13.2–27.2) |

| Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bayesian Results | Traditional Frequentist Results | |||||

| PCB Category 1 | Value (ng/g Lipid) | n | BPOR 2 | Probability OR > 1 | Logistic Regression 3 | OR for ASD in Lyall et al. [21] 4 |

| PCB118 | ||||||

| Q1 | <1.4 | 108 | 1.0 (referent) | 0% | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Q2 | 1.4-<2.3 | 143 | 0.93 (0.57, 1.44) | 38% | 1.57 (0.27, 11.3) | 1.29 (0.86, 1.95) |

| Q3 | 2.3-<3.6 | 170 | 1.00 (0.62, 1.53) | 50% | 0.49 (0.07, 3.74) | 1.38 (0.90, 2.11) |

| Q4 | ≥3.6 | 125 | 1.20 (0.72, 1.89) | 77% | NA 5 | 1.15 (0.72, 1.82) |

| PCB138 | ||||||

| Q1 | <3.2 | 175 | 1.0 | 0% | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Q2 | 3.2-<5.5 | 184 | 1.21 (0.79, 1.76) | 82% | 3.10 (0.53, 28.0) | 1.39 (0.92, 2.10) |

| Q3 | 5.5-<8.9 | 118 | 1.36 (0.84, 2.09) | 91% | NA 5 | 1.34 (0.87, 2.07) |

| Q4 | ≥8.9 | 69 | 1.76 (0.99, 2.92) | 98% | NA 5 | 1.79 (1.10, 2.92) |

| PCB153 | ||||||

| Q1 | <4.2 | 87 | 1.0 | 0% | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Q2 | 4.2-<7.4 | 178 | 1.36 (0.80, 2.16) | 89% | 1.98 (0.27, 41.4) | 1.32 (0.88, 1.99) |

| Q3 | 7.4-<11.7 | 144 | 1.09 (0.62, 1.78) | 63% | 0.19 (0.01, 5.90) | 1.24 (0.80, 1.93) |

| Q4 | ≥11.7 | 137 | 1.82 (1.02, 3.02) | 98% | 0.19 (0.01, 6.50) | 1.82 (1.10, 3.02) |

| PCB170 | ||||||

| Q1 | <1.5 | 227 | 1.0 | 0% | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Q2 | 1.5-<2.6 | 141 | 0.90 (0.60, 1.31) | 30% | 0.46 (0.08, 2.11) | 1.15 (0.76, 1.76) |

| Q3 | 2.6-<4.3 | 110 | 1.04 (0.65, 1.58) | 57% | NA5 | 1.17 (0.75, 1.83) |

| Q4 | ≥4.3 | 68 | 1.39 (0.80, 2.24) | 90% | 0.30 (0.01, 2.71) | 1.48 (0.88, 2.50) |

| PCB180 | ||||||

| Q1 | <3.4 | 154 | 1.0 | 0% | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Q2 | 3.4-<6.1 | 182 | 0.63 (0.40, 0.96) | 19% | 0.33 (0.06, 1.78) | 1.00 (0.66, 1.50) |

| Q3 | 6.1-<10.4 | 120 | 0.79 (0.46, 1.24) | 18% | 0.11 (0.00, 1.10) | 1.17 (0.75, 1.81) |

| Q4 | ≥10.4 | 90 | 1.20 (0.67, 1.98) | 75% | 0.14 (0.01, 1.58) | 1.49 (0.89, 2.49) |

| PCB187 | ||||||

| Q1 | <0.92 | 197 | 1.0 | 0% | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Q2 | 0.92-<1.8 | 124 | 0.92 (0.60, 1.34) | 62% | 0.60 (0.10, 2.95) | 0.89 (0.58, 1.36) |

| Q3 | 1.8-<3.3 | 135 | 0.99 (0.65, 1.44) | 48% | 0.23 (0.02, 1.42) | 1.22 (0.79, 1.87) |

| Q4 | ≥3.3 | 90 | 1.46 (0.89, 2.24) | 95% | NA 5 | 1.32 (0.79, 2.20) |

| Sum of above PCBs | ||||||

| Q1 | <33.4 | 358 | 1.0 | 0% | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Q2 | 33.4-<55.3 | 110 | 1.32 (0.88, 1.92) | 92% | 0.32 (0.02, 2.16) | 1.08 (0.72, 1.63) |

| Q3 | 55.3-<86.3 | 51 | 1.44 (0.82, 2.36) | 91% | NA 5 | 0.99 (0.64, 1.51) |

| Q4 | ≥86.3 | 27 | 1.97 (0.90, 3.77) | 97% | NA 5 | 1.36 (0.88, 2.11) |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bernardo, B.A.; Lanphear, B.P.; Venners, S.A.; Arbuckle, T.E.; Braun, J.M.; Muckle, G.; Fraser, W.D.; McCandless, L.C. Assessing the Relation between Plasma PCB Concentrations and Elevated Autistic Behaviours using Bayesian Predictive Odds Ratios. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 457. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16030457

Bernardo BA, Lanphear BP, Venners SA, Arbuckle TE, Braun JM, Muckle G, Fraser WD, McCandless LC. Assessing the Relation between Plasma PCB Concentrations and Elevated Autistic Behaviours using Bayesian Predictive Odds Ratios. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(3):457. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16030457

Chicago/Turabian StyleBernardo, Brendan A., Bruce P. Lanphear, Scott A. Venners, Tye E. Arbuckle, Joseph M. Braun, Gina Muckle, William D. Fraser, and Lawrence C. McCandless. 2019. "Assessing the Relation between Plasma PCB Concentrations and Elevated Autistic Behaviours using Bayesian Predictive Odds Ratios" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 3: 457. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16030457

APA StyleBernardo, B. A., Lanphear, B. P., Venners, S. A., Arbuckle, T. E., Braun, J. M., Muckle, G., Fraser, W. D., & McCandless, L. C. (2019). Assessing the Relation between Plasma PCB Concentrations and Elevated Autistic Behaviours using Bayesian Predictive Odds Ratios. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(3), 457. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16030457