Causal Modelling for Supporting Planning and Management of Mental Health Services and Systems: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

- Intervention (I): Causal modelling, including BNs and SEM (as a simplification of a BN), for guiding and supporting planning and management of MHSS [54].

- Comparator (C): Refers to a control group or comparison intervention (PICO is a guide for designing research questions based on structured search strategies in a clinical framework). In our study, it is not applicable.

- Outcome (O): Any resulting expert-based or data-based causal model.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Study Selection, Data Collection, and Summary Measures

2.4. Quality Assessment

3. Results

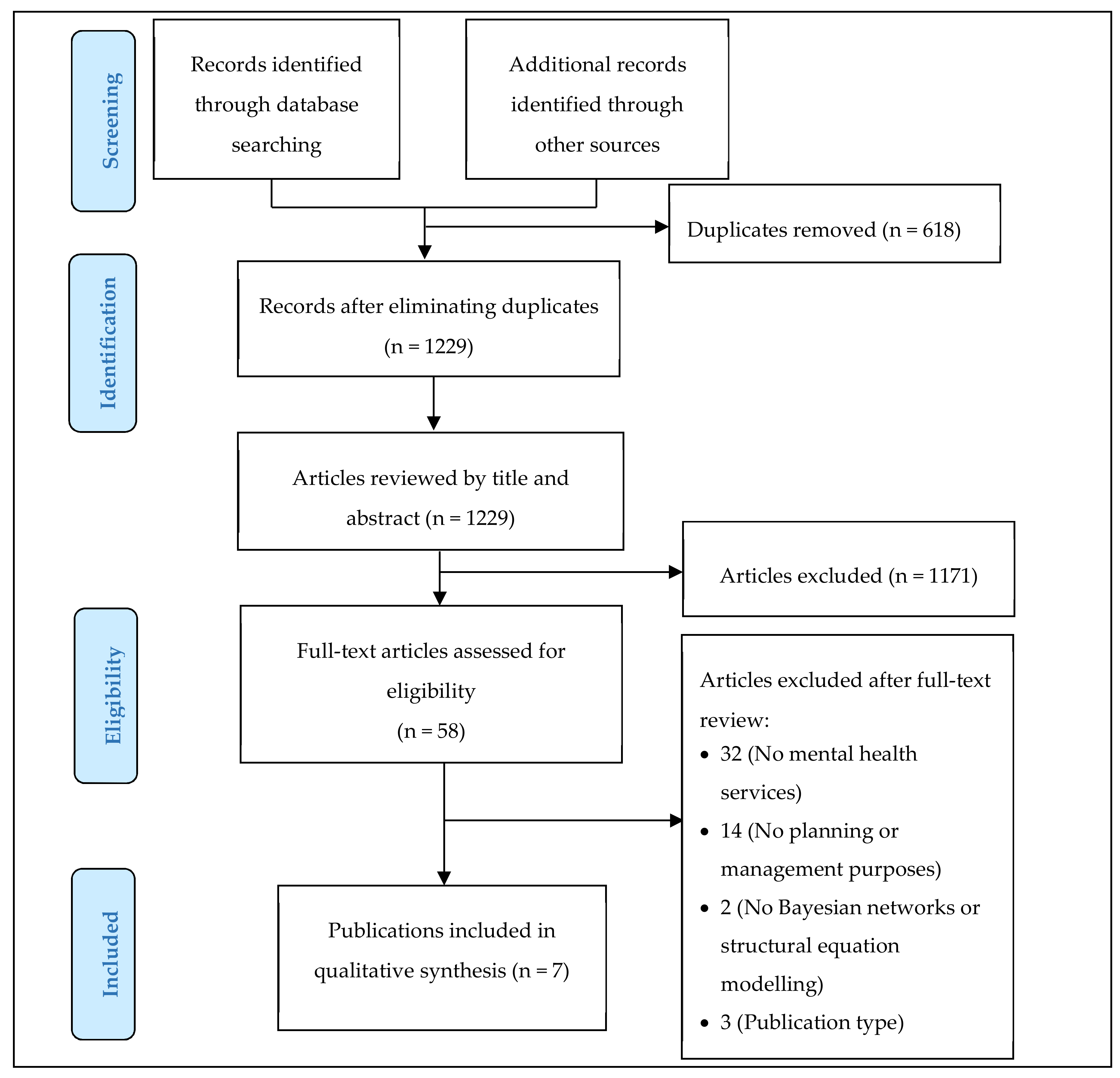

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.2.1. Country and Year

3.2.2. Objectives

3.2.3. Types of Mental Health Services and Systems

3.2.4. Target Population

3.2.5. Data

3.2.6. Variables

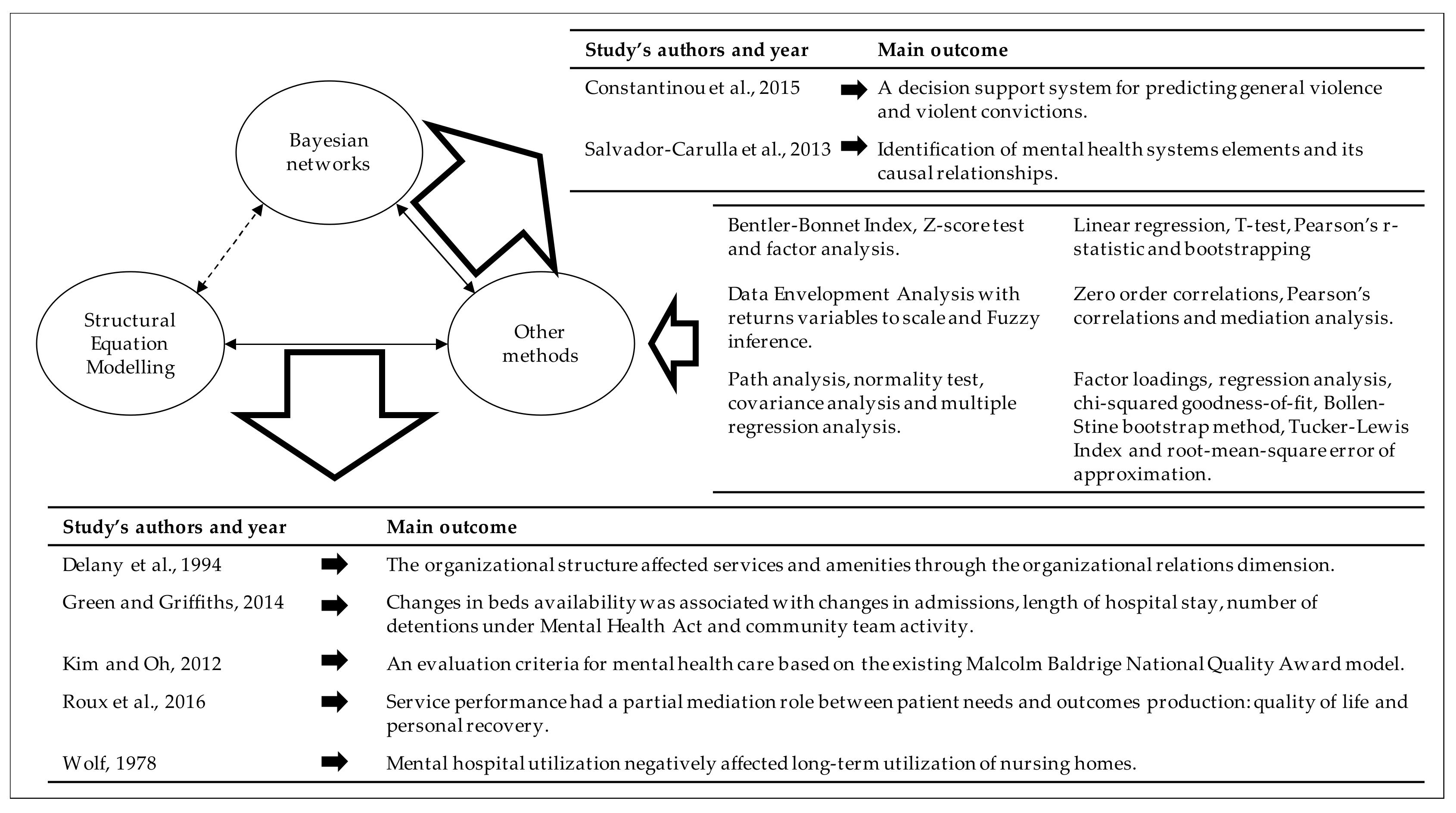

3.2.7. Methods

3.3. Main Findings

3.4. Quality of Included Studies

3.5. Implications for Policy-Making in Mental Health Care

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thornicroft, G.; Tansella, M. Better Mental Health Care; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Thornicroft, G.; Tansella, M. A conceptual framework for mental health services: The matrix model. Psychol. Med. 1998, 28, 503–508. [Google Scholar]

- Thornicroft, G.; Szmukler, G.; Mueser, K.T.; Drake, R.E. Oxford Textbook of Community Mental Health; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; ISBN 9780199565498. [Google Scholar]

- Bouras, N.; Ikkos, G.; Craig, T. From Community to Meta-Community Mental Health Care. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibert, K.; García-Alonso, C.; Salvador-Carulla, L. Integrating clinicians, knowledge and data: Expert-based cooperative analysis in healthcare decision support. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2010, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvador-Carulla, L.; Haro, J.M.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L. A framework for evidence-based mental health care and policy. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2006, 111, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vigo, D.; Thornicroft, G.; Atun, R. Estimating the true global burden of mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry 2016, 3, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, D.E.; Cafiero, E.; Jané-Llopis, E.; Abrahams-Gessel, S.; Reddy Bloom, L.; Fathima, S.B.; Feigl, A.; Gaziano, T.; Hamandi, A.; Mowafi, M.; et al. The Global Economic Burden of Noncommunicable Diseases. World Econ. Forum 2011, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trautmann, S.; Rehm, J.; Wittchen, H.-U. The economic costs of mental disorders: Do our societies react appropriately to the burden of mental disorders? EMBO Rep. 2016, 17, 1245–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, P.; Patel, V.; Joestl, S.; March, D.; Insel, T.; Daar, A.; Anderson, W.; A Dhansay, M.; Phillips, A.; Shurin, S.; et al. Grand Challenges in Global Mental Health. Nature 2011, 475, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Mental Health Action Plan 2013-2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; ISBN 978-9241506021. [Google Scholar]

- Pathare, S.; Brazinova, A.; Levav, I. Care gap: A comprehensive measure to quantify unmet needs in mental health. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2018, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thornicroft, G. Most people with mental illness are not treated. Lancet 2007, 370, 807–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, J.; Codony, M.; Kovess, V.; Angermeyer, M.C.; Steven, J.; Haro, J.M.; Girolamo, G.D.E.; Graaf, R.O.N.D.E.; Demyttenaere, K.; Vilagut, G.; et al. Population level of unmet need for mental healthcare in Europe service AUTHOR ’ S PROOF Population level of unmet need for mental healthcare in Europe *. Br. J. Psychiatry 2007, 190, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, G.; Cuijpers, P.; Craske, M.G.; McEvoy, P.; Titov, N. Computer Therapy for the Anxiety and Depressive Disorders Is Effective, Acceptable and Practical Health Care: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, H.; Pallister, E.; Smale, S.; Hickie, I.B.; Calear, A.L. Community-Based Prevention Programs for Anxiety and Depression in Youth: A Systematic Review. J. Prim. Prev. 2010, 31, 139–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sin, J.; Gillard, S.; Spain, D.; Cornelius, V.; Chen, T.; Henderson, C. Effectiveness of psychoeducational interventions for family carers of people with psychosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 56, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correl, C.U.; Galling, B.; Pawar, A.; Krivko, A.; Boneto, C.; Ruggeri, M.; Craig, T.; Nordentoft, M.; Srihari, V.; Guloksuz, S.; et al. Comparison of early intervention services vs treatment as usual for early-phase psychosis: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. JAMA Psychiatry 2018, 75, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvestri, F.; Peters, J. An Introduction to the International Initiative for Mental Health Leadership (IIMHL). Int. J. Leadersh. Public Serv. 2007, 3, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beinecke, R.H.; Daniels, A.; Peters, J.; Silvestri, F. Guest Editors’ Introduction: The International Initiative for Mental Health Leadership (IIMHL): A Model for Global Knowledge Exchange. Int. J. Ment. Health 2009, 38, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador-Carulla, L.; Amaddeo, F.; Gutiérrez-Colosía, M.R.; Salazzari, D.; Gonzalez-Caballero, J.L.; Montagni, I.; Tedeschi, F.; Cetrano, G.; Chevreul, K.; Kalseth, J.; et al. Developing a tool for mapping adult mental health care provision in Europe: The REMAST research protocol and its contribution to better integrated care. Int. J. Integr. Care 2015, 15, e042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador-Carulla, L.; Garcia-Alonso, C.; Gibert, K.; Vázquez-Bourgon, J. Incorporating local information and prior expert knowledge to evidence-informed mental health system research. In Improving Mental Health Care; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 211–228. ISBN 9781118337981. [Google Scholar]

- Constantinou, A.C.; Fenton, N.; Marsh, W.; Radlinski, L. From complex questionnaire and interviewing data to intelligent Bayesian network models for medical decision support. Artif. Intell. Med. 2016, 67, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Jiménez, M.; García-Alonso, C.R.; Salvador-Carulla, L.; Fernández-Rodríguez, V. Evaluation of system efficiency using the Monte Carlo DEA: The case of small health areas. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2015, 242, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearl, J. Causality: Models, Reasoning and Inference, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; ISBN 052189560X, 9780521895606. [Google Scholar]

- Constantinou, A.C.; Fenton, N.; Neil, M. Integrating expert knowledge with data in Bayesian networks: Preserving data-driven expectations when the expert variables remain unobserved. Expert Syst. Appl. 2016, 56, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenland, S.; Pearl, J.; Robins, J.M. Causal diagrams for epidemiologic research. Epidemiology 1999, 10, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yet, B.; Bastani, K.; Raharjo, H.; Lifvergren, S.; Marsh, W.; Bergman, B. Decision support system for Warfarin therapy management using Bayesian networks. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 55, 488–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topuz, K.; Zengul, F.D.; Dag, A.; Almehmi, A.; Bayram, M. Predicting graft survival among kidney transplant recipients: A Bayesian decision support model. Decis. Support Syst. 2018, 106, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Haug, P.J. Exploiting missing clinical data in Bayesian network modeling for predicting medical problems. J. Biomed. Inform. 2008, 41, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashion, A.K.; Hathaway, D.K.; Stanfill, A.; Thomas, F.; Ziebarth, J.D.; Cui, Y.; Cowan, P.A.; Eason, J. Pre-transplant predictors of one yr weight gain after kidney transplantation. Clin. Transplant. 2014, 28, 1271–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curiac, D.; Vasile, G.; Banias, O.; Volosencu, C.; Albu, A. Bayesian Network Model for Diagnosis of Psychiatric Diseases. In Proceedings of the ITI 2009 31st International Conference on Information, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 22–25 June 2009. [Google Scholar]

- McNally, R.J. Can network analysis transform psychopathology? Behav. Res. Ther. 2016, 86, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorias, S. Overcoming the limitations of the descriptive and categorical approaches in psychiatric diagnosis: A proposal based on bayesian networks. Turk Psikiyatr. Derg. 2015, 26, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estabragh, Z.S.; Mansour, M.; Kashani, R.; Moghaddam, F.J.; Sari, S. Bayesian Network Model for Diagnosis of Social Anxiety Disorder. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine Workshops (BIBMW), Atlanta, GA, USA, 12–15 November 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.; Hung, W.; Juang, T. Depression Diagnosis based on Ontologies and Bayesian Networks. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Manchester, UK, 13–16 October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ojeme, B.; Mbogho, A. Selecting Learning Algorithms for Simultaneous Identification of Depression and Comorbid Disorders. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2016, 96, 1294–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seixas, F.L.; Zadrozny, B.; Laks, J.; Conci, A.; Muchaluat Saade, D.C. A Bayesian network decision model for supporting the diagnosis of dementia, Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Comput. Biol. Med. 2014, 51, 140–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, P.R.; De Castro, A.K.A.; Pinheiro, M.C.D. A Multicriteria Model Applied in the Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Bayesian Network. In Proceedings of the 2008 11th IEEE International Conference on Computational Science and Engineering, Sao Paulo, Brazil, 16–18 July 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Goodson, J.; Jang, W. Assessing nursing home care quality through Bayesian networks. Health Care Manag. Sci. 2008, 11, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. mhGAP Intervention Guide for Mental, Neurological, and Substance Use Disorders in Non-Specialized Health Settings. Version 2.0; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Joint Commissioning Panel for Mental Health. Rehabilitation Services for People with Complex Mental Health Needs; Joint Commissioning Panel for Mental Health: UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dieterich, M.; Irving, C.B.; Bergman, H.; Khokhar, M.A.; Park, B.; Marshall, M. Intensive case management for severe mental illness (review). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, CD007906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansella, M.; Thornicroft, G.; Lempp, H. Lessons from community mental health to drive implementation in health care systems for people with long-term conditions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 4714–4728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, M.; Lockwood, A. Assertive community treatment for people with severe mental disorders (Review). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2000, 2, CD001089. [Google Scholar]

- McKay, C.; Nugent, K.L.; Johnsen, M.; Eaton, W.W.; Lidz, C.W. A Systematic Review of Evidence for the Clubhouse Model of Psychosocial Rehabilitation. Adm. Policy Ment. Heal. Ment. Heal. Serv. Res. 2016, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador-Carulla, L.; García-Alonso, C.R.; González-Caballero, J.L.; Garrido-Cumbrera, M. Use of an operational model of community care to assess technical efficiency and benchmarking of small mental health areas in Spain. J. Ment. Health Policy Econ. 2007, 10, 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Altman, D.; Antes, G.; Atkins, D.; Barbour, V.; Barrowman, N.; Berlin, J.A.; et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement (Chinese edition). J. Chin. Integr. Med. 2009, 7, 889–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priebe, S.; Saidi, M.; Want, A.; Mangalore, R.; Knapp, M. Housing services for people with mental disorders in England: Patient characteristics, care provision and costs. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2009, 44, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killaspy, H.; Priebe, S.; Bremner, S.; McCrone, P.; Dowling, S.; Harrison, I.; Krotofil, J.; McPherson, P.; Sandhu, S.; Arbuthnott, M.; et al. Quality of life, autonomy, satisfaction, and costs associated with mental health supported accommodation services in England: A national survey. Lancet Psychiatry 2016, 3, 1129–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador-Carulla, L.; Alvarez-Galvez, J.; Romero, C.; Gutiérrez-Colosía, M.R.; Weber, G.; McDaid, D.; Dimitrov, H.; Sprah, L.; Kalseth, B.; Tibaldi, G.; et al. Evaluation of an integrated system for classification, assessment and comparison of services for long-term care in Europe: The eDESDE-LTC study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013, 13, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagni, I.; Salvador-Carulla, L.; Mcdaid, D.; Straßmayr, C.; Endel, F.; Näätänen, P.; Kalseth, J.; Kalseth, B.; Matosevic, T.; Donisi, V.; et al. The REFINEMENT Glossary of Terms: An International Terminology for Mental Health Systems Assessment. Adm. Policy Ment. Heal. Ment. Heal. Serv. Res. 2017, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.; Kuhlmann, R. The European Service Mapping Schedule (ESMS): Development of an instrumentfor the description and classificationof mental health services. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2000, 102, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearl, J. An Introduction to Causal Inference. Int. J. Biostat. 2010, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killaspy, H.; White, S.; Dowling, S.; Krotofil, J.; McPherson, P.; Sandhu, S.; Arbuthnott, M.; Curtis, S.; Leavey, G.; Priebe, S.; et al. Adaptation of the Quality Indicator for Rehabilitative Care (QuIRC) for use in mental health supported accommodation services (QuIRC-SA). BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, B.H.; Ciliska, D.; Dobbins, M.; Micucci, S. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: Providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid.-Based Nurs. 2004, 1, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, R.S. A social systems model of nursing home use. Health Serv. Res. 1978, 13, 111–128. [Google Scholar]

- Roux, P.; Passerieux, C.; Fleury, M.-J. Mediation analysis of severity of needs, service performance and outcomes for patients with mental disorders. Br. J. Psychiatry 2016, 209, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delany, P.J.; Fletcher, B.W.; Lennox, R.D. Analyzing shelter organizations and the services they offer: Testing a structural model using a sample of shelter programs. Eval. Progr. Plann. 1994, 17, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.K.; Oh, H.J. Causality analysis on health care evaluation criteria for state-operated mental hospitals in Korea using Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award Model. Community Ment. Health J. 2012, 48, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinou, A.C.; Freestone, M.; Marsh, W.; Coid, J. Causal inference for violence risk management and decision support in forensic psychiatry. Decis. Support Syst. 2015, 80, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, B.H.; Griffiths, E.C. Hospital admission and community treatment of mental disorders in England from 1998 to 2012. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2014, 36, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeniemi, M.; Almeda, N.; Salinas-Pérez, J.A.; Gutiérrez-Colosía, M.R.; García-Alonso, C.; Ala-Nikkola, T.; Joffe, G.; Pirkola, S.; Wahlbeck, K.; Cid, J.; et al. A Comparison of Mental Health Care Systems in Northern and Southern Europe: A Service Mapping Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2018, 15, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador-Carulla, L.; Tibaldi, G.; Johnson, S.; Scala, E.; Romero, C.; Munizza, C. Patterns of mental health service utilisation in Italy and Spain. An investigation using the European Service Mapping Schedule. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2005, 40, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Colosia, M.R.; Salvador-Carulla, L.; Salinas-Perez, J.A.; Garcia-Alonso, C.R.; Cid, J.; Salazzari, D.; Montagni, I.; Tedeschi, F.; Cetrano, G.; Chevreul, K.; et al. Standard comparison of local mental health care systems in eight European countries. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2017, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Acronym | Description |

|---|---|

| MHSS | Mental health services and systems |

| DSS | Decision support system |

| BN | Bayesian network |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modelling |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PROSPERO | International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews |

| ICC | Intra-Class Correlation |

| B-MHCC | Basic Mental Health Community Care |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| MBNQA | Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award |

| DEA | Data Envelopment Analysis |

| BCC | Returns variables to scale |

| Identifies All Types of Mental Health Services [Title/Abstract] |

|---|

| 1. "Mental health" |

| 2. "Mental disorder*" |

| 3. "Mental illness*" |

| 4. "Psychiatric disorder*" |

| 5. "Psychopathology" |

| 6. 1 OR 2 OR 3 OR 4 OR 5 |

| Identifies methods for causality assessment [Title/Abstract] |

| 7. "Bayesian network*" |

| 8. "Causal model" |

| 9. "Causal reasoning" |

| 10. 6 OR 7 OR 8 OR 9 |

| 11. 6 AND 10 |

| Identifies All Types of Mental Health Services [Title/Abstract] |

|---|

| 1. "Mental health" |

| 2. "Mental health care" |

| 3. "Mental health service*" |

| 4. "Mental health system*" |

| 5. "Psychiatric care" |

| 6. "Psychiatric hospital*" |

| 7. "Inpatient care" |

| 8. "Residential Care" |

| 9. "Outpatient care" |

| 10. "Day care" |

| 11. "Community mental health cent*" |

| 12. "Residential facilit*" |

| 13. "Residential service*" |

| 14. "Assisted living facilit*" |

| 15. "Halfway house*" |

| 16. "Nursing home*" |

| 17. "Support* accom*" |

| 18. "Support* tenanc*" |

| 19. "Floating support" |

| 20. "Floating outreach" |

| 21. 1 OR 2 OR 3 OR 4 OR 5 OR 6 OR 7 OR 8 OR 9 OR 10 OR 11 OR 12 OR 13 OR 14 OR 15 OR 16 OR 17 OR 18 OR 19 OR 20 |

| Identifies methods for causality assessment [Title/Abstract] |

| 22. "Bayesian network*" |

| 23. "Structural equation*" |

| 24. "Causal model*" |

| 25. "Causal reasoning" |

| 26. 22 OR 23 OR 24 OR 25 |

| Identifies terms of management and planning [All fields] |

| 27. "Manag*" |

| 28. "Decision Support" |

| 29. "Decision making" |

| 30. "Expert knowledge" |

| 31. "Planning" |

| 32. 27 OR 28 OR 29 OR 30 OR 31 |

| 33. 21 AND 26 AND 32 |

| Authors, Year and Country | Objectives | Type of MHSS | Target Population | Data | Variables (Scale) | Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constantinou et al., 2015, United Kingdom | To develop a decision support system for violence risk assessment and risk management in patients discharged from medium secure services (DSVM-MSS). | Medium secure services that provide accommodation, support, and treatment. | Patients with mental health problems. Total of 386 patients discharged from medium secure services. Total of 953 prisoners, of whom 594 are mentally ill (anger management, drug misuse treatment, alcohol misuse treatment, cocaine dependence, cannabis dependence, stimulants dependence, and alcohol dependence). All of them are 18 years old or older. | Datasets were collected from The Validation of New Risk Assessment Instrument for Use with patients Discharged from Medium Secure Service, Prisoner Cohort Study, and criminal records retrieved by the Police National Computer. | IQ, Structured leisure activities, Stable and suitable work, Effective coping skills, Steady income, Positive life goals, Pro-social and supportive network, Professionally supervised living, Problems with intimate relationships, Problems with other relationships, Problems with employment, Social avoidance, Self-control, Inadequate planning, Personal resources, Expert, Delusions, Hallucinations, Anxiety, Depression, Grandiosity, Psychotic illness, Cannabis use, Cannabis use post treatment, Cocaine use, Cocaine use posttreatment, Heroin use, Stimulants use, Stimulants use posttreatment, Opiates use, Hazardous drinking, Alcohol treatment, Hazardous drinking posttreatment, Drug treatment, Cannabis dependence, Cocaine dependence, Heroin dependence, Stimulants dependence, Opiates dependence, Alcohol dependence, Substance dependence, Disinhibition, Excessive substance use, Personality disorder, PCLSV factor 1, PCLSV factor 2, PCLSV facet 3, Poor parenting, Secure attachment in childhood, Instability, Problems with ASB as adult, Motivation for treatment, Motivated to use medication, Uncooperativeness, Negative attitude, Problems with responsiveness, Lack of insight, Medication at discharge, Tension, Guilt feelings, Affective lability, Anger, Anger management, Anger posttreatment, Excitement, Suspiciousness, Hostility, Difficulty delaying gratification, Emotional withdrawal, Aggression, Uncontrolled aggression, Gender, Age, Length of stay as inpatient, Pro-criminal attitude, Victimization, Violent ideation or intend, Serious problems with violence, Prior serious offences, General violence and Violent convictions. All group 2: Service user´s characteristics. | Bayesian network (BN): expert knowledge for constructing the causal structure of the (BN), binary factors and combinatorial rules, conditional probability tables, expectation maximization algorithm, graph surgery, area under the curve (AUC) of a receiver operating characteristic measure, leave-one-out cross-validation, causal-related inference, T-test, and sensitivity analysis (tornado graphs). |

| Delany et al., 1994, United States of America | To develop a model to test the effect of organizational structure on organizational relations and on services and amenities, both of them being mediated by organizational relations. | A total of 192 shelter organizations that provided overnight accommodation; health, substance abuse, and mental health services in 29 cities in the continental United States. | Service users without access to adequate and usual accommodations. | Data were collected using a survey questionnaire sent to shelter directors or managers. The questionnaire included information about organizational funding, affiliation, mission, and target population; relationships with groups in the community; perceptions of the stability of the environment; obstacles to operation (zoning, health code issues, lack of transportation); and operational policies, including level of formalization and centralization, staffing patterns, problems with staff, staff autonomy and routine, and services and amenities. | Organizational structure: formalization, autonomy, specialization, routinization, knowledge complexity, and centralization. All group 1: Resources. Organizational relations: diversity of funding, relationships, constraints, and independence. All group 1: Resources. Services and amenities: Personal maintenance needs, case management services, and health substance abuse and mental health services. All group 1: Resources. | Structural Equation Modelling (SEM), covariance analysis, Bentler-Bonnet Index, Z-score test, and confirmatory factor analysis. |

| Green and Griffiths, 2014, United Kingdom | To analyze trends in hospital and community treatment in England. | Mental health services of NHS England: NHS hospitals, NHS funded beds in independent hospitals, NHS mental health teams, community crisis teams, and community psychiatric services. | Adults diagnosed with eight severe diagnoses: schizophrenia (F20), bipolar affective disorder (31), depressive disorder (F32), recurrent depressive disorder (F33), eating disorder (F50), mental and behavioural disorder due to use of alcohol (F10), unspecified dementia (F03), and reaction to stress and adjustment disorders (F43), according to ICD-10 diagnostic categories. | Data were collected from 1998 to 2012 across NHS England from the UK Government Health and Social Care Information Centre, the published Health Episode Statistics spreadsheets on primary diagnosis of admissions, the annual open records of community crisis team in England from 2003 to 2010, and the UK Department of Health. | Annual numbers of available hospital beds Group 1: Resources. Eight ICD-10 adult mental disorder Group 2: Service user’s characteristics. Hospital admissions, median length of stay, annual numbers of Mental Health Act detentions, and community team activity. Group 3: Service performance and outcomes. | Linear regression, Pearson’s r-statistic, SEM, parametric bootstrap, and two-tailed t test. |

| Kim and Oh, 2012, Korea | To develop health care evaluation criteria for mental health care according to the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award model (MBNQA). | Five state-operated mental hospitals in Korea. | Service users of the hospitals under analysis. | Authors developed a survey based on the MBNQA and previous findings. The survey was directed to physician, nurses, medical technicians, pharmacists, and administrative staff at the five state-operated hospitals across Korea. | Driver: Leadership. Direction: Strategic planning. System: Human Resources Orientation; Process Management; and Patient, customer, & Market Orientation. Foundation: Measurement, Analysis, & Knowledge management. Group 1: Resources. Results: Hospital Performance. Group 3: Service performance and outcomes. | Confirmatory factor analysis and SEM analysis. |

| Roux et al., 2016, Canada | To analyze the role of service performance as a mediating factor between severity of patient’s needs and outcomes. | Mental health service networks from Quebec, including the hospital department of psychiatry, multidisciplinary mental health primary care team, community-based mental health agencies, general practitioners and psychologists practicing in private clinics, and community mental health housing resources. | Adults from 18 to 70 years old, diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorders, mood, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive, personality, attention-deficit hyperactivity, or stressor-related disorders, according to DSM-5 diagnostic categories. | Datasets were collected from five questionnaires: Montreal Assessment of Needs Questionnaire (MANQ), Alberta Continuity of Services Scale for Mental Health, Recovery Self-Assessment Scale, Satisfaction with Life Domains Scale, and Recovery Assessment Scale. | Needs: Intensity of needs (Montreal Assessment of Needs Questionnaire). Group 2: Service user’s characteristics. Service performance: Adjusted adequacy of help (Montreal Assessment of Needs Questionnaire), Continuity of care (Alberta Continuity of Services Scale for Mental Health), and Recovery service orientation (Recovery Self-Assessment Scale, revised person-in-recovery version). Outcomes: Quality of life (Satisfaction with Life Domains Scale) and Personal recovery (Recovery Assessment Scale). Group 3: Service performance and outcomes. | Zero order correlations, Pearson’s correlations, bootstrap method with 2000 iterations; SEM and mediation analysis. Factor loadings, regression analyses, non-parametric model-based bootstrapping with 2000 iterations, chi-squared goodness-of-fit statistic, Bollen-Stine bootstrap method, Tucker-Lewis Index, and root-mean-square error of approximation. |

| Salvador-Carulla et al., 2013, Spain | To improve the relative technical efficiency assessment by establishing causal relationships among variables. | Seventy-one small mental health areas in Andalucía (Spain). The main type of care provided, according to the ESMS/DESDE-LTC coding, is acute and non-acute care (hospital), residential nonhospital care, day acute and non-acute care, and other structured activities. | Adults who had experienced mental disorders. | Datasets were retrieved by The Public Mental Health System of Andalusia (Spain). | Public health budget, professional workers, and accessibility. Group 1: Resources. Risks factors for mental health and psychiatric morbidity. Group 2: Service user’s characteristics. Treated prevalence in a small health area in a specific year t (patients_t), patients already in contact with mental health community service in the year t-1 (patients_t-1), new patients who contact the specialized community services in this year (new patients_t), activities with patients, and relative technical efficiency. Group 3: Service performance and outcomes. | “Bayesian network Data Envelopment Analysis model”: Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) with returns variables to scale (BCC), BN integrating fuzzy rules base to interpret causal relationships, interpretation of efficiency variables according to rule-base “if…then” (Model of Basic Mental Health Community Care). Services are standardized using ESMS/DESDE-LTC classification system. |

| Wolf, 1978, United States of America | To analyze the effect of sociocultural and health-resource variables on long-term-care utilization. | Thirty-nine mental health catchment areas of Massachusetts, including 901 nursing homes. The 901 nursing homes housed 49,471 residents. The 901 nursing homes included 38 chronic disease and rehabilitation hospitals, which provided accommodation for 5803 service users. Hospital care, care in general hospitals, and nursing home care. | Patients who lived in the catchment area where the facilities were located. Patients 65 and older who were admitted to Massachusetts Department Mental Health, discharged from general hospitals, of home health care programs, and patients 60 and older in nursing homes and chronic disease and rehabilitation hospitals. | Datasets were collected from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, the state-wide survey for assessing community programs sponsored by the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health, and the survey conducted by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health. | Community Care Resources and Primary Care Resources. Group 1: Resources. Socioeconomic Status, Marital Status/Living Arrangement, Age, Ethnicity, Race, and Urbanization. Group 2: Service user’s characteristics. Mental Hospital Utilization, General Hospital Utilization, and Long-Term Care Utilization. Group 3: Service performance and outcomes. | Path analysis, path coefficients, test of variable distributions for normality, regression analysis, factor analysis, covariance analysis, path diagram, zero-order correlations, and multiple regression equations. |

| Study | Complexity | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Constantinou et al., 2015 | Single MHSS Micro level | 1. The decision support system “DSVM-MSS” predicted general violence (area under the curve scores = 0.691 (pre-discharge) and 0.730 (post-discharge); this difference is not statistically significant (p = 0.472)) and violent convictions (area under the curve scores = 0.845 (pre-discharge) and 0.774 (post-discharge); this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.469)) in people with mental health problems living in medium secure services. |

| Delany et al., 1994 | Single MHSS Micro level | 1. The direct relationship between organizational structure (formalization, autonomy, specialization, routinization, knowledge complexity, and centralization) and service amenities (personal maintenance needs, case management services, and health substance abuse and mental health services) was not statistically significant (z = 0.363). 2. The direct relationship between organizational structure and organizational relations (diversity of funding, relationships, constraints, and independence) was statistically significant beyond the 0.01 level (z = 3.152). 3. The direct relationship between organizational relations and services amenities was not statistically significant (z = 1.482). 4. The organizational structure affected services and amenities (personal maintenance needs, case management services, and health-substance abused and MHS) through the organizational relations dimension, including funding, relationships, constrains, and independence. 5. The model showed a good reproduction of the observed covariance matrix for the following variables: specialization; diversity of funding; relationships; constrains; personal maintenance needs; case management services; and health, substance abuse, and mental health services: ξ2 (11) = 18.908, p = 0.06275; Bentler-Bonnet Fit Index = 0.84. |

| Kim and Oh, 2012 | Single MHSS Micro level | 1. Leadership positively and significantly (p = 0.000) impacted Measurement, Analysis, and Knowledge Management; Strategic Planning; Patient, Customer, and Market Orientation; and Human Resources Orientation. Leadership did not significantly impact Process Management (p = 0.574) or Hospital Performance (p = 0.190). 2. Strategic Planning positively and significantly (p = 0.000) affected Patient, Customer, and Market Orientation and Process Management(p = 0.004), and it did not impact significantly on Human Resources Orientation (p = 0.492). 3. Patient, Customer, and Market Orientation positively and significantly impacted Hospital Performance (p = 0.000) and Process Management (p = 0.017). 4. Human Resources Orientation impacted Process Management (p = 0.000) and Hospital Performance (p = 0.000). 5. Process Management positively influenced Hospital Performance (p = 0.000). 6. Measurement, Analysis, and Knowledge Management positively impacted Strategic Planning; Patient, Customer, and Market Orientation; Human Resources Orientation; and Process Management (p = 0.000). 7. The structural model showed the following results: χ2 = 14.034 (df = 3), p = 0.012, χ2/df = 4.678, Goodness-of-fit Index = 0.994, Root Mean Residual = 0.009, Normed Fit Index = 0.997, and Confirmatory Fit Index = 0.998. |

| Wolf, 1978 | Single MHSS Micro and Meso levels | 1. Mental hospital utilization had a weak and negative impact on long-term utilization of nursing homes (r = −0.071). 2. Catchment areas where there are more admissions of elderly people had a higher percentage of urban (β = −0.089), non-white (β = 0.074), aged persons (β = 0.105) and more persons unmarried and living alone (β = 0.160). The proportion of foreign-born people did not influence the model (β = 0.001). This model explained 9% of the variance in mental hospital utilization. |

| Green and Griffiths, 2014 | Group of MHSSs Micro level | 1. The reduction of beds availability entailed an annual inpatient admissions decrease in: depression (β = −1085; p < 0.01), dementia (β = −764; p < 0.01), schizophrenia (β = −468; p < 0.01), bipolar disorder (β = −159; p < 0.01), and OCD (β = −21; p < 0.01); and increase in use of alcohol (β = 1764; p < 0.01), eating disorders (β = 55; p < 0.01), and posttraumatic stress disorder (β = 17; p < 0.01). 2. The reduction of beds availability significantly decreased length of hospital stay in: use of alcohol (β = −0.29, p < 0.001), eating disorders (β = −0.52, p < 0.001), dementia (β = −0.55, p < 0.001), and depression (β = −0.96, p < 0.001). 3. The reduction of beds availability increased the number of detentions under Mental Health Act (β = 298, p < 0.01). 4. The number of mental health beds was negatively associated with the number of psychiatric severe admissions (coefficient = −0.683; p < 0.001, bootstrapped 95% CI: 0.37 to 1.06). 5. The number of beds was negatively associated with community team activity (coefficient = −0.521; p < 0.001, bootstrapped 95% CI: −0.71 to 0.25). 6. The community team activity was not associated with inpatient admissions (coefficient = −0.121, p < 0.001, bootstrapped 95% CI: −0.35 to 0.42). 7. The model (a path from community team activity to hospital beds and from hospital beds to hospital admissions) showed good fit: χ2 = 0.57; df = 1; p = 0.45; Tucker–Lewis Index = 1.07, root mean square error of approximation = 0.00. |

| Roux et al., 2016 | Group of MHSSs Micro level | 1. Patient needs (adaptation to stress, social exclusion, involvement in treatment decisions, and job integration) and outcomes (quality of life and personal recovery) were negatively associated (β = −0.60; p < 0.001). 2. Service performance (type and amount of support provided) and outcomes were positively associated (β = 0.40; p < 0.001). 3. Patient needs and service performance were negatively associated (β = −0.30; p < 0.001). 4. The model provided a good fit for the data, as suggested by the following statistics: non-significant goodness-of-fit based on the Bollen–Stine bootstrap distribution ((7) = 14.3, p = 0.107), TLI above 0.95 (TLI = 0.967) and RMSEA not statistically greater than 0.05 (RMSEA = 0.056, one-sided P = 0.358). The model explained 67% of the variance in outcomes. 5. Service performance had a partial mediation role between needs and outcome. A total of 16.4% of the impact of needs on outcomes was mediated by service performance (standard error: 0.05, z = 3.6, p < 0.001 with the Bollen–Stine bootstrap method after 2000 iterations). |

| Salvador-Carulla et al., 2013 | Group of MHSSs Meso level | 1. The treated prevalence of a small health area during a specific year was the result of combining service users that were in contact with the mental health service (during the year t-1) and the new services users who contacted the specialized mental health services within this year. Psychiatric morbidity was the root variable, which caused the treated incidence of new patients and the treated prevalence of patients who were in contact with mental health community services. Treated prevalence directly influenced workforce capacity, relative technical efficiency, and activities with patients. Another root variable is public health budget, directly related to workforce capacity. Accessibility was the third root variable that influenced the treated incidence of new patients. |

| Quality Assessment Statements | Constantinou et al., 2015 | Delany et al., 1994 | Kim and Oh, 2012 | Green and Griffiths, 2014 | Roux et al., 2016 | Salvador-Carulla et al., 2013 | Wolf, 1978 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Includes more than one type of mental health service or system | X | X | X | ||||

| 2. Specifies more than one type of target population for care delivery | X | X | X | ||||

| 3. Variables include resources and outcomes of the mental health care | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 4. Includes a causal graph | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| 5. Takes into account external expert knowledge for identifying the nodes and the causal relationships of the causal graph | X | X | X | X | |||

| 6. Combines data and external expert-based knowledge | X | X | X | X | |||

| 7. Include sensitivity or parametric analysis | X | X | X | X | |||

| 8. Carries out factorial confirmatory/exploratory analysis | X | X | X | ||||

| 9. Develops causal-related inference | X | X | |||||

| 10. The causal model is integrated in a decision support system | X | X |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Almeda, N.; García-Alonso, C.R.; Salinas-Pérez, J.A.; Gutiérrez-Colosía, M.R.; Salvador-Carulla, L. Causal Modelling for Supporting Planning and Management of Mental Health Services and Systems: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 332. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16030332

Almeda N, García-Alonso CR, Salinas-Pérez JA, Gutiérrez-Colosía MR, Salvador-Carulla L. Causal Modelling for Supporting Planning and Management of Mental Health Services and Systems: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(3):332. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16030332

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmeda, Nerea, Carlos R. García-Alonso, José A. Salinas-Pérez, Mencía R. Gutiérrez-Colosía, and Luis Salvador-Carulla. 2019. "Causal Modelling for Supporting Planning and Management of Mental Health Services and Systems: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 3: 332. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16030332

APA StyleAlmeda, N., García-Alonso, C. R., Salinas-Pérez, J. A., Gutiérrez-Colosía, M. R., & Salvador-Carulla, L. (2019). Causal Modelling for Supporting Planning and Management of Mental Health Services and Systems: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(3), 332. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16030332