Black Women’s Confidence in the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Sample and Setting

2.2. Measures

2.3. Data Analysis

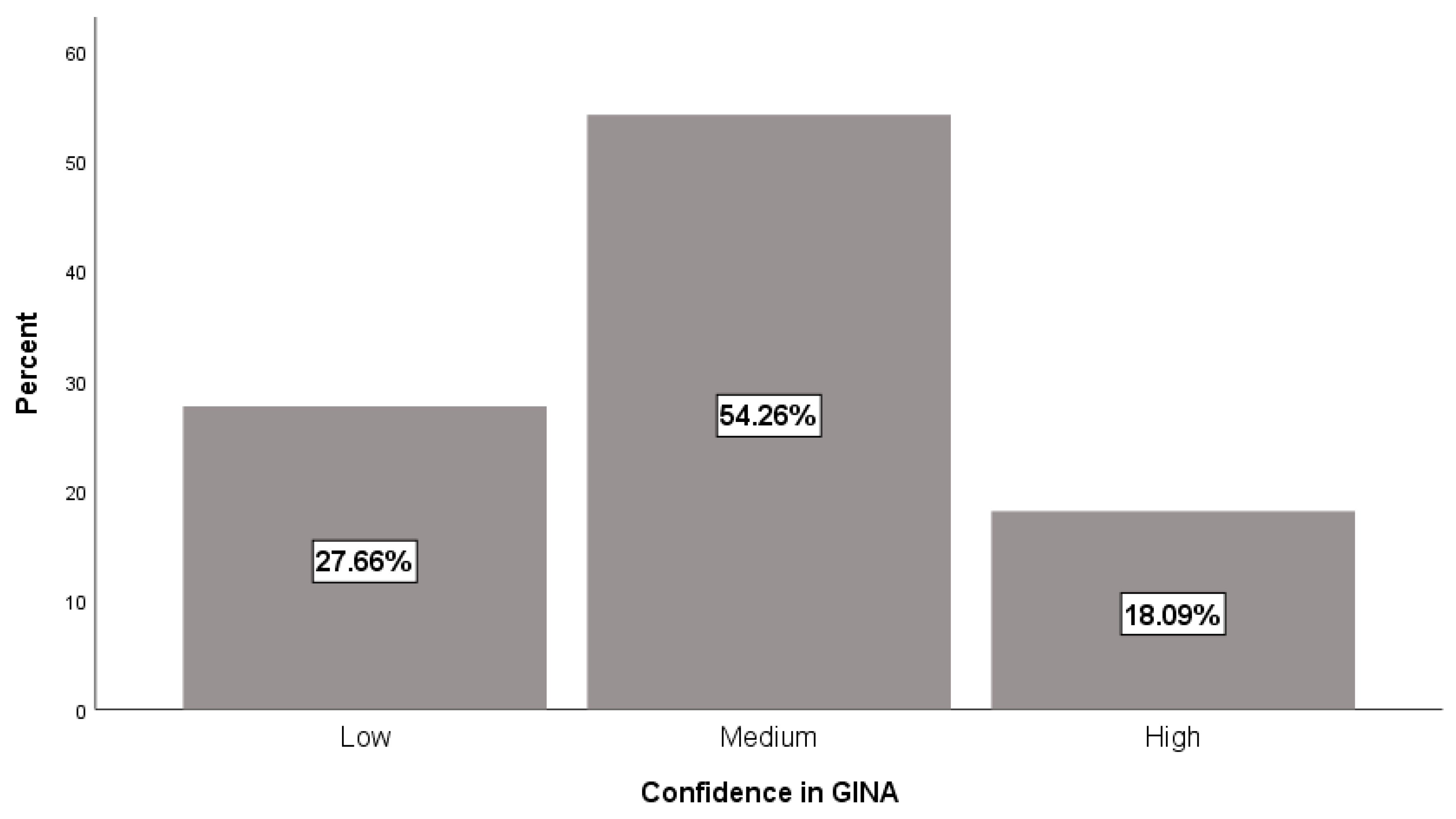

3. Results

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- DeSantis, C.E.; Ma, J.; Goding Sauer, A.; Newman, L.A.; Jemal, A. Breast cancer statistics, 2017, racial disparity in mortality by state. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2017, 67, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietze, E.C.; Chavez, T.A.; Seewaldt, V.L. Obesity and Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Disparities, Controversies, and Biology. Am. J. Pathol. 2018, 188, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietze, E.C.; Sistrunk, C.; Miranda-Carboni, G.; O’Regan, R.; Seewaldt, V.L. Triple-negative breast cancer in African-American women: Disparities versus biology. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2015, 15, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keegan, T.H.M.; Kurian, A.W.; Gali, K.; Tao, L.; Lichtensztajn, D.Y.; Hershman, D.L.; Habel, L.A.; Caan, B.J.; Gomez, S.L. Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic differences in short-term breast cancer survival among women in an integrated health system. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 938–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lessick, M. Genetic testing for breast and ovarian cancer: Ethical, legal, and psychosocial considerations. Nurs. Women’s Health 2007, 11, 390–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, K.; Micco, E.; Carney, A.; Stopfer, J.; Putt, M. Racial differences in the use of BRCA1/2 testing among women with a family history of breast or ovarian cancer. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2005, 293, 1729–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheppard, V.B.; Mays, D.; La Veist, T.; Tercyak, K.P. Medical mistrust influences black women’s level of engagement in BRCA1/2 genetic counseling and testing. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2013, 105, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cragun, D.; Weidner, A.; Lewis, C.; Bonner, D.; Kim, J.; Vadaparampil, S.T.; Pal, T. Racial disparities in BRCA testing and cancer risk management across a population-based sample of young breast cancer survivors. Cancer 2017, 123, 2497–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn, B.A.; Chawla, N.; Bastani, R. Barriers to genetic testing for breast cancer risk among ethnic minority women: An exploratory study. Ethn. Dis. 2012, 22, 267–273. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, A.M.; Bristol, M.; Domchek, S.M.; Groeneveld, P.W.; Kim, Y.; Motanya, U.N.; Shea, J.A.; Armstrong, K. Health care segregation, physician recommendation, and racial disparities in BRCA1/2 testing among women with breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 2610–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, I.; Christopher, J.; Williams, K.P.; Sheppard, V.B. What Black Women Know and Want to Know About Counseling and Testing for BRCA1/2. J. Cancer Educ. 2015, 30, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheppard, V.B.; Graves, K.D.; Christopher, J.; Hurtado-De-Mendoza, A.; Talley, C.; Williams, K.P. African American women’s limited knowledge and experiences with genetic counseling for hereditary breast cancer. J. Genet. Couns. 2014, 23, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, M.S.; Petrucelli, N. Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome: The impact of race on uptake of genetic counseling and testing. Methods Mol. Biol. 2009, 471, 487–500. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008. Available online: https://www.genome.gov/27568492/the-genetic-information-nondiscrimination-act-of-2008/ (accessed on 6 December 2017).

- Rothstein, M.A. Currents in contemporary ethics: GINA, the ADA, and genetic discrimination in employment. J. Law Med. Ethics 2008, 36, 837–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pamarti, A. Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) and Its Effect on Genetic Counseling Practice: A Survey of Genetic Counselors. Master’s Thesis, Brandeis University, Waltham, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Green, R.; Lautenbach, D.; McGuire, A. GINA, Genetic Discrimination, and Genomic Medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 2013–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allain, D.C.; Friedman, S.; Senter, L. Consumer awareness and attitudes about insurance discrimination post enactment of the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act. Fam. Cancer 2012, 11, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.L.; Kwan, K.; Quispe Ortiz, L.; Zamora Maass, M. Law and Norms: A Machine Learning Approach to Predicting Attitudes Towards Abortion. SSRN Electron. J. 2016. Available online: https://www.nber.org/~dlchen/papers/Law_and_Norms.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2019).

- Martin, N.D.; Rigoni, D.; Vohs, K.D.; Fiske, S.T. Free will beliefs predict attitudes toward unethical behavior and criminal punishment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 7325–7330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, K.; Calzone, K.; Stopfer, J.; Fitzgerald, G.; Coyne, J.; Weber, B. Factors associated with decisions about clinical BRCA1/2 testing. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2000, 9, 1251–1254. [Google Scholar]

- Erblich, J.; Brown, K.; Kim, Y.; Valdimarsdottir, H.B.; Livingston, B.E.; Bovbjerg, D.H. Development and validation of a breast cancer genetic counseling knowledge questionnaire. Patient Educ. Couns. 2005, 56, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendy, J.; Lyons, E.; Breakwell, G.M. Genetic testing and the relationship between specific and general self-efficacy. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2006, 11, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halbert, C.H.; Schwartz, M.D.; Wenzel, L.; Narod, S.; Peshkin, B.N.; Cella, D.; Lerman, C. Predictors of cognitive appraisals following genetic testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. J. Behav. Med. 2004, 27, 373–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bird, S.T.; Bogart, L.M. Perceived race-based and socioeconomic status(SES)-based discrimination in interactions with health care providers. Ethn. Dis. 2001, 11, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Laveist, T.A.; Isaac, L.A.; Williams, K.P. Mistrust of health care organizations is associated with underutilization of health services. Health Serv. Res. 2009, 44, 2093–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, R.; Likhanov, M.; Selita, F.; Zakharov, I.; Smith-Woolley, E.; Kovas, Y. New literacy challenge for the twenty-first century: Genetic knowledge is poor even among well educated. J. Community Genet. 2019, 10, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkenstadt, M.; Shiloh, S.; Barkai, G.; Katznelson, M.; Goldman, B. Perceived personal control (PPC): A new concept in measuring outcome of genetic counseling. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1999, 82, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieterse, A.H.; Ausems, M.G.E.M.; Spreeuwenberg, P.; van Dulmen, S. Longer-term influence of breast cancer genetic counseling on cognitions and distress: Smaller benefits for affected versus unaffected women. Patient Educ. Couns. 2011, 85, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prohibiting Genetic Discrimination to Promote Science, Health, and Fairness. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2019, 3, 104.

- Suter, S.M. GINA at 10 years: The battle over “genetic information” continues in court. J. Law Biosci. 2018, 5, 495–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | n (%) | Mean (SD) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intrapersonal | |||

| Age (M ± SD) | 44.9 (11.4) | 0.20 | |

| ≤50 years | 62 (66.0) | 10.8 (2.5) | |

| >50 years | 32 (34.0) | 10.4 (2.7) | 0.44 |

| Marital Status | 0.36 | ||

| Married/Living as married | 39 (41.5) | 10.6 (2.7) | |

| Single (never married) | 38 (40.4) | 10.8 (2.7) | |

| Other | 17 (18.1) | 10.7 (2.9) | |

| Education Level Attained | 0.04 * | ||

| Less than or equal to high school | 16 (17.0) | 11.6 (2.3) | |

| Greater than high school | 78 (83.0) | 10.5 (2.6) | |

| Insurance Status | 0.13 | ||

| Has insurance | 87 (92.6) | 10.7 (2.6) | |

| Does not have insurance | 7 (7.4) | 10.7 (1.7) | |

| Work Arrangement | 0.84 | ||

| Full time employed | 71 (75.5) | 10.9 (2.5) | |

| Not full time employed | 23 (24.5) | 9.9 (2.6) | |

| Cancer Status | 0.24 | ||

| Diagnosed | 46 (48.9) | 10.9 (2.6) | |

| Not diagnosed | 48 (51.1) | 10.5 (2.5) | |

| GCT Engagement | 0.70 | ||

| Yes | 15 (22.7) | 10.6 (2.9) | |

| No | 51 (77.3) | 10.8 (2.7) | |

| Attitude toward GCT | 41.0 (4.0) | 0.63 | |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | 14.0 (2.0) | 0.001 ‡ | |

| Knowledge of GCT | 8.3 (1.9) | 0.64 | |

| Value in GCT | 11.3 (1.9) | 0.06 | |

| Confidence in GCT | 13.8 (2.2) | 0.12 | |

| Interpersonal | |||

| Race-Based Discrimination | 2.4 (2.4) | 0.021 * | |

| Structural | |||

| Medical Mistrust | 24.9 (3.9) | 0.36 | |

| Difficulty obtaining GCT | 13.0 (3.6) | 0.42 | |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sutton, A.L.; Henderson, A.; Hurtado-de-Mendoza, A.; Tanner, E.; Khan, M.; Quillin, J.; Sheppard, V.B. Black Women’s Confidence in the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 5112. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16245112

Sutton AL, Henderson A, Hurtado-de-Mendoza A, Tanner E, Khan M, Quillin J, Sheppard VB. Black Women’s Confidence in the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(24):5112. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16245112

Chicago/Turabian StyleSutton, Arnethea L., Alesha Henderson, Alejandra Hurtado-de-Mendoza, Erin Tanner, Mishaal Khan, John Quillin, and Vanessa B. Sheppard. 2019. "Black Women’s Confidence in the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 24: 5112. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16245112

APA StyleSutton, A. L., Henderson, A., Hurtado-de-Mendoza, A., Tanner, E., Khan, M., Quillin, J., & Sheppard, V. B. (2019). Black Women’s Confidence in the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(24), 5112. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16245112