Grief Experiences in Family Caregivers of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Codes Grouped under The “Diagnostic Process” Category

3.1.1. Anticipation

3.1.2. Age and Professional Who Communicated the Diagnosis

3.2. Codes Grouped under The “Grief Process” Category

3.2.1. Reaction to The Diagnosis

3.2.2. Disruption of Expectations: Differences Regarding the Children’s Future.

3.2.3. Grieving Experience

3.3. Codes Grouped under the “Grieving Process” Category

3.3.1. Discontinued Activities and Time for Oneself

3.3.2. Changes in Family Dynamics

3.3.3. Differences, According to Sex, as to Whether There Is Anything Family Members Would Like to Recover

3.3.4. Gains

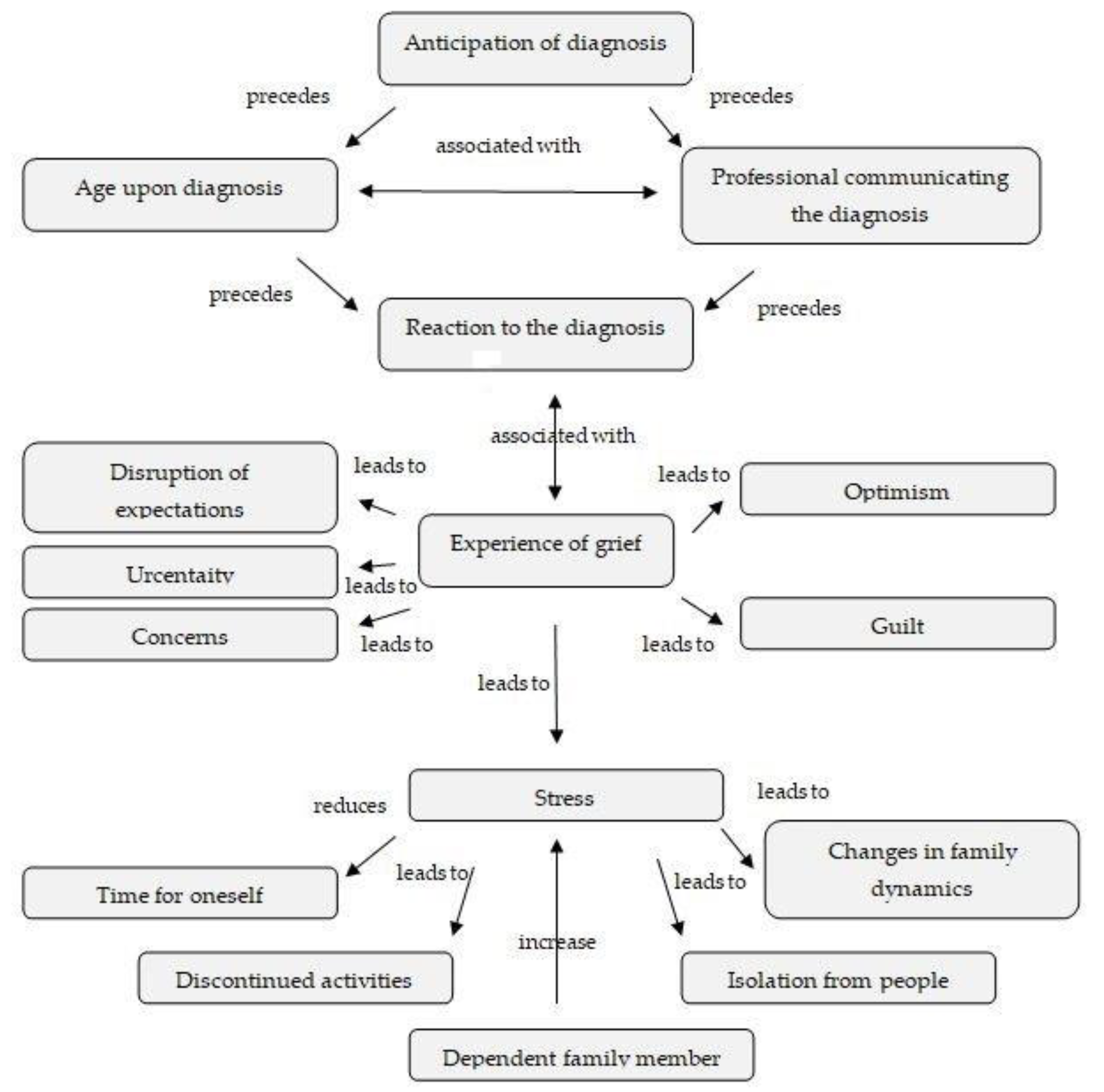

3.3.5. Integration of Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/autism-spectrum-disorders (accessed on 2 April 2018).

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Chaparro, S. Autismo y Síndrome de Asperger; Alianza Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mansell, W.; Morris, K. A survey of parents’ reactions to the diagnosis of an autistic spectrum disorder by a local service: Access to information and use of services. Autism 2004, 8, 387–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honey, E.; Hastings, R.P.; Mcconachie, H. Use of the Questionnaire on Resources and Stress (QRS-F) with parents of young children with autism. Autism 2005, 9, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altiere, M.J.; von Kluge, S. Family functioning and coping behaviors in parents of children with autism. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2009, 18, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cridland, E.K.; Jones, S.C.; Caputi, P.; Magee, C.A. Qualitative research with families living with autism spectrum disorder: Recommendations for conducting semistructured interviews. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2015, 40, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatzoyia, D.; Kotsis, K.; Koullourou, I.; Goulia, P.; Carvalho, A.F.; Soulis, S.; Hyphantis, T. The association of illness perceptions with depressive symptoms and general psychological distress in parents of an offspring with autism spectrum disorder. Disabil. Health J. 2014, 7, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovagnoli, G.; Postorino, V.; Fatta, L.M.; Sanges, V.; De Peppo, L.; Vassena, L.; &Mazzone, L. Behavioral and emotional profile and parental stress in preschool children with autism spectrum disorder. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2015, 45, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karp, E.A.; Kuo, A.A.; Sandler, J.; Suarez, Z.F. Maternal Mental Health After a Child’s Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2015, 313, 81–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- O’Halloran, M.; Sweeney, J.; Doody, O. Exploring fathers’ perceptions of parenting a child with Asperger syndrome. J. Intellect. Disabil. 2013, 17, 198–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seguí, J.D.; Ortiz-Tallo, M.; De Diego, Y. Factores asociados al estrés del cuidador primario de niños con autismo: Sobrecarga, psicopatología y estado de salud. Psicol. Ann. Psychol. 2008, 24, 100–105. [Google Scholar]

- Ludlow, A.; Skelly, C.; Rohleder, P. Challenges faced by parents of children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. J. Health Psychol. 2012, 17, 702–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.P.; Steffgen, G.; Ferring, D. Contributors to well-being and stress in parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2017, 37, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabrowska, A.; Pisula, E. Parenting stress and coping styles in mothers and fathers of pre-school children with autism and Down syndrome. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2010, 54, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pottie, C.G.; Ingram, K.M. Daily stress, coping, and well-being in parents of children with autism: A multilevel modeling approach. J. Fam. Psychol. 2008, 22, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasilopoulou, E.; Nisbet, J. The quality of life of parents of children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2016, 23, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromley, J.; Hare, D.J.; Davison, K.; Emerson, E. Mothers supporting children with autistic spectrum disorders: Social support, mental health status and satisfaction with services. Autism 2004, 8, 409–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodgate, R.L.; Ateah, C.; Secco, L. Living in a world of our own: The experience of parents who have a child with autism. Qual. Health Res. 2008, 18, 1075–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, M. Ambiguous loss in families of children with autism spectrum disorders. Fam. Relat. 2007, 56, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulligan, J.; MacCulloch, R.; Good, B.; Nicholas, D.B. Transparency, hope, and empowerment: A model for partnering with parents of a child with autism spectrum disorder at diagnosis and beyond. Soc. Work Ment. Health 2012, 10, 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponte, J.; Perpiñán, S.; Mayo, M.E.; Millá, M.G.; Pegenaute, F.; Poch-Olivé, M.L. Estudio sobre los procedimientos profesionales, las vivencias y las necesidades de los padres cuando se les informa de que su hijo tiene una discapacidad o un trastorno del desarrollo. La primera noticia. Rev. Neurol. 2012, 54, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Boss, P. Ambiguous loss research, theory, and practice: Reflections after 9/11. J. Marriage Fam. 2004, 66, 551–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boss, P. Ambiguous Loss: Learning to Live with Unresolved Grief; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, L.B.; Zanksas, S.; Meindl, J.N.; Parra, G.R.; Cogdal, P.; Powell, K. Parental symptoms of posttraumatic stress following a child’s diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder: A pilot study. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2012, 6, 1186–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiman, T. Parents of children with disabilities: Resilience, coping, and future expectations. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 2002, 14, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olshansky, S. Chronic sorrow: A response to having a mentally defective child. Soc. Casework 1962, 43, 190–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rarity, J.C. Nonfinite Grief in Families with Children on the Autism Spectrum; ProQuest: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick-Ott, A.; Ladd, L.D. The blending of Boss’s concept of ambiguous loss and Olshansky’s concept of chronic sorrow: A case study of a family with a child who has significant disabilities. J. Creat. Ment. Health 2010, 5, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, E.J.; Schultz, C.L. Nonfinite Loss and Grief: A Psychoeducational Approach; Paul H Brookes Publishing: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, M.; Bernard, P.; Forge, J. Communicating a diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder-a qualitative study of parents’ experiences. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2013, 18, 370–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, G.A.; Zwaigenbaum, L.; King, S.; Baxter, D.; Rosenbaum, P.; Bates, A. A qualitative investigation of changes in the belief systems of families of children with autism or Down syndrome. Child Care Health Dev. 2006, 32, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, H.; Saleemi, M.; Riaz, H.; Hassan, Y.; Khan, F. Coping strategies of mothers with ASD children. Prof. Med. J. 2015, 22, 1454–1463. [Google Scholar]

- Fernańdez-Alcántara, M.; García-Caro, M.P.; Pérez-Marfil, M.N.; Hueso-Montoro, C.; Laynez-Rubio, C.; Cruz-Quintana, F. Feelings of loss and grief in parents of children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Res. Dev. Disabil. 2016, 55, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, H.R.; Patterson, B.J.; Klein, J. Coping with autism: A journey toward adaptation. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2012, 27, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, V.; Long, B.C. Coping processes as revealed in the stories of mothers of children with autism. Qual. Health Res. 2010, 20, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine Publishing: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.L.; Corbin, J.; Zimmerman, E. Bases de la Investigación Cualitativa: Técnicas y Procedimientos Para Desarrollar la Teoría Fundamentada; Aldine: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtzer-White, E.; Luterman, D. Families and children with hearing loss: Grief and coping. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2003, 9, 232–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomen, L. Tratando el Proceso de Duelo y de Morir; Pirámide Psicología: Madrid, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Canal, R.; Martín, M.V.; Bohórquez, D.; Guisuraga, Z.; Herráez, L.; Herráez, M.; Posada, M. La detección precoz del autismo y el impacto en la calidad de vida de las familias. In Aplicación del Paradigma de Calidad de Vida. VII Seminario de Actualización Metodológica en Investigación Sobre Discapacidad; INICO: Salamanca, Spain, 2010; pp. 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, J.S. A Mythopoetic Exploration of Maternal Grief: When a Child Is Diagnosed on the Autism Spectrum; Pacifica Graduate Institute: Bárbara, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ozgul, S. Parental grief and serious mental illness: A narrative. Aust. N. Z. J. Fam. 2004, 25, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, E.; Mâsse, L.C.; Iarocci, G. A psychometric study of the Family Resilience Assessment Scale among families of children with autism spectrum disorder. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2019, 17, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, F. Family resilience: A framework for clinical practice. Fam. Process 2003, 42, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhana, A.; Bachoo, S. The determinants of family resilience among families in low-and middle-income contexts: A systematic literature review. S. Afr. J. Psychol. 2011, 41, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawley, D.R. Clinical implications of family resilience. Am. J. Fam. Ther. 2000, 28, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, M. Resilience concepts and findings: Implications for family therapy. J. Fam. Ther. 1999, 21, 119–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgin, H.; Kucuk, L. Raising an autistic child: Perspectives from Turkish mothers. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2010, 23, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour, M.; Wood, C.; Giallo, R.; Jellett, R. Fatigue, stress and coping in mothers of children with an autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2013, 43, 1547–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picci, R.L.; Oliva, F.; Trivelli, F.; Carezana, C.; Zuffranieri, M.; Ostacoli, L.; Furlan, P.M.; Lala, R. Emotional burden and coping strategies of parents of children with rare diseases. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2015, 24, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worden, J.W. Grief Counseling and Grief Therapy: A Handbook for the Mental Health Practitioner; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Subject | Sex | Age | Level of Education | Marital Status | Employment Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | Female | 36 | Secondary education or vocational training | Married | Unemployed |

| 02 | Female | 32 | Secondary education or vocational training | Married | Unemployed |

| 03 | Female | 40 | Secondary education or vocational training | Separated/divorced | Unemployed |

| 04 | Female | 40 | Secondary education or vocational training | Married | Employed |

| 05 | Female | 57 | Secondary education or vocational training | Widow | Employed |

| 06 | Female | 45 | Graduate | Separated/divorced | Unemployed |

| 07 | Female | 42 | University studies | Married | Employed |

| 08 | Female | 31 | Secondary education or vocational training | Married | Unemployed |

| 09 | Female | 40 | Secondary education or vocational training | Married | Unemployed |

| 10 | Female | 48 | Secondary education or vocational training | Married | Employed |

| 11 | Male | 37 | Graduate | Married | Employed |

| 12 | Male | 35 | Secondary education or vocational training | Married | Employed |

| 13 | Female | 45 | Basic education | Married | Unemployed |

| 14 | Female | 30 | Secondary education or vocational training | Single | Employed |

| 15 | Male | 40 | Basic education | Married | Unemployed |

| 16 | Female | 40 | University studies | Separated/divorced | Employed |

| 17 | Female | 68 | Secondary education or vocational training | Married | Household chores |

| 18 | Female | 40 | Secondary education or vocational training | Married | Household chores |

| 19 | Female | 43 | Graduate | Married | Employed |

| 20 | Male | 45 | University studies | Married | Employed |

| Subject | Age (months) | Professional |

|---|---|---|

| 01 | 36 | Psychologist |

| 02 | 24 | Psychiatrist |

| 03 | 27 | Psychologist |

| 04 | 18 | Herself |

| 05 | 54 | Psychologist |

| 06 | 23 | Psychologist |

| 07 | 17 | Neuropaediatrician |

| 08 | 18 | Psychologist |

| 09 | 132 | Counsellor |

| 10 | 120 | Psychologist |

| 11 | 18 | Paediatrician |

| 12 | 24 | Psychologist |

| 13 | 42 | Neurologist |

| 14 | 36 | General practitioner |

| 15 | 24 | Psychologist |

| 16 | 30 | Psychiatrist |

| 17 | - | Neurologist |

| 18 | 84 | Psychiatrist |

| 19 | 60 | Psychologist |

| 20 | 66 | Psychologist |

| Section 1: Diagnosis | Who communicated the diagnosis to the relative? At what age? How did you feel at the moment you were communicated? What were your reactions? What concerns came to mind? |

| Section 2: Loss and grieving process | Interference in work, leisure, friendship, family, care people and relationship, health, welfare in general. Associated emotions. Perceived losses. |

| Section 3: Caregiver overload | Activities that you used to do and have stopped doing now. Do you spend time for yourself? How much per week and how? How has it affected family dynamics? |

| Section 4: Future | Has your vision changed about the future of your family member due to diagnosis? Could you explain it? |

| DiagnosticProcess | Grief Process | Stress and Overload |

|---|---|---|

| Anticipation | Reaction to the diagnosis | Discontinued activities and time for oneself |

| Age of the child | Disruption of expectations | Changes in family dynamics |

| Professional who communicated the diagnosis | Experience of grief | Feelings of loss/gain |

| Subcode | Quotations from the Participants |

|---|---|

| Shock | “In shock. The stereotype of autism that I had was more exaggerated, so I didn’t think my son had this.” (07-Mother) “I didn’t know how to react, I was shocked. I didn’t know what to do, or how to act, or... this is horrible... unbearable...” (17-Grandmother) |

| Denial | “Petrified. I thought: This is not happening to me. And then I thought: Why me? What will become of my son?” (05-Mother) |

| Guilt | “My world fell apart.It crossed my mind whether I had been a good mother.” (09-Mother) |

| Anger | “I felt an intense rage and then frustration afterwards: Why me? I felt helpless not knowing how to deal with the situation... uncertainty.” (11-Father) “Awful, I don’t want to say it because I’m going to cry. I felt rage... why did this happen to me?!” (18-Mother) |

| Proactive attitude | “I felt like I wanted to fight. I thought: now that I know what my child’s got, we’re going to work on this. I reacted proactively. I got down to work: looking for information and resources everywhere. I avoid standing still.” (03-Mother) “I felt that you have to try harder, press harder, and take more care of the situation.” (20-Father) |

| Emotion | Quotations |

|---|---|

| Concern and uncertainty | “A healthy girl who would run and jump, happily. Now I don’t know, I’m not quite sure. Her autonomy is what worries me the most.” (01-Mother) “Now his future is a question mark. It depends on his progress. What I want is for him to be independent and to be able to lead a life like everybody else.” (02-Mother) “Now I’m very worried about my son’s future. That’s what worries me the most, if he will be able to become independent, autonomous. I’m worried that society will take advantage of him […]. I’m very concerned that there will be no more resources for him, that there are finite resources.” (07-Mother) “A normal future, with a job... Now I really don’t know. That’s what worries me the most.” (09-Mother) “Very different. I imagined that I was going to be able to talk to him, that I was going to teach him my stuff, sports... and that he was going to have an education. Now, I really don’t know what’s going to happen, if he can’t speak...” (12-Mother) “I didn’t used to think much about the future, but I imagined him beingwell, happy. Now I don’t know, I’m hopeless. Sometimes I think about giving him a sibling, but I’m afraid.” (14-Mother) “The usual... where is he going to study? Will I teach him English?... The usual... Now, I’m scared and you think what will become of him when I’m gone...? The million dollar question.” (16-Mother) “With my wife, several children, a simple life, and making a living. Now it hurts because I wanted to have another child and take more care of them. And I’m concerned for the day we are gone.” (20-Father) |

| Disappointment | “We all expect to have a perfect child, and that’s the letdown we get. Because that’s the child we lose.” (04-Mother) “I thought that he would be a university student, that he would play football, be a good person, an athlete... now I think of him as totally dependent, always asking to have good people around to take care of him.” (05-Mother) “Before, when he was younger, it came to mind a lot what it would be like without the diagnosis. I really wanted to have a child to enjoy it: when they started to walk, to talk... and I’ve been left with the desire to enjoy my son’s normal early stages.”(07-Mother) “I thought that he’d be an amusing kid, very talkative… a little rascal” (08-Mother) “I wanted some intellectually gifted children, super clever, and now what... My friends, with their children, who are super good at something whereas mine, what... well...” (13-Mother) “[…] that now you have to be dedicated to him for everything, I imagined him on a motorbike and now... you see... not anymore.” (15-Father) “Like everybody else, I wanted to have three children, very nice, like everybody else... my studios arein Madrid... And now I’m gloomy, always with my son, he is totally dependent and I don’t trust anyone.” (18-Mother) |

| Resignation | “I pictured him studying, with his friends, with his girlfriend... a normal life. Now, I don’t even think about the future, what for?” (06-Mother) “Well, having my grandson, pampering him, taking him to the streets, to the cinema, drawings... talking to him... now I don’t have a future, I don’t want to think about it, it scares me so much...” (17-Grandmother) |

| Optimism | “I wanted my children to travel, to be independent, to go to university... to be free people. Now I think the same way, or at least I hope so. It’s improving a lot.” (04-Mother) “Like anyone else: university studies, football... now I still think the same way, or I’d like to think the same way. Instead of football, chess... let him be happy with whatever it is. If instead of football he likes to learn the roads, so be it.” (11-Father) |

| Emotion | Quotations |

|---|---|

| Unresolved grief | “For me the grief is worse now than at the time of diagnosis, because I see how L. is and I’m worried about the future.” (01-Mother) “It’s been worse for me. Because when I lost my parents, it hurt, but it’s something I had accepted would happen. But not this.” (05-Mother) “Yes, to me it’s something similar. I keep experiencing it inside. I experienced it in this way: they give you the diagnosis and you have to ride it out. I made sure I didn’t have time to grieve by looking for therapies and resources everywhere.” (11-Father) |

| Cyclical grief | “It’s not the same to me. Grieving for a diagnosis of ASD is a cycle of grief that you enter and exit continuously. Each stage of the child’s development makes you worry about some things and it makes you grieve again.” (07-Mother) “Yes, it’s similar. It changes everything for you. It’s as though I had to learn everything from him. I have to learn to deal with him. And then there are days when you just can’t accept that your child has ASD. You have ups and downs. The grief goes up and down, up and down.” (08-Mother) |

| Grieving for the loss of the expected child | “Yes, it’s not the same because the person is there, but it’s not what you had in mind. When you consider having a child, you don’t expect this. And I really thought about it.” (01-Mother) “Yes, it’s as if you’ve lost your child. We all expect to have a perfect child, and that’s the letdown we get. Because that’s the child we lose” (04-Mother) “It may resemble something like that, because what you imagine when you’re having a baby vanishes, so it’s like you’re losing something of yourself.” (12-Mother) “It’s not like a bereavement, no. It’s like... now what? Uncertainty. I wanted to have intellectually gifted children, super clever, and now what? …” (13-Mother) |

| Chronic sorrow orlatent grief | “It’s very similar, but it’s more painful. Because when you lose someone you learn to live without them, and now you learn to live with them, it’s exactly the opposite.” (06-Mother) “No, not so much, but I’m always trying to make sure that he does not suffer, that people don’t deceive him... it hurts so much that I have inappropriate outbursts at times.” (10-Mother) “No, it felt worse than the death of a loved one. My father died, I have already experienced that, but this is worse than the death of a loved one. It’s like a living sorrow. It never ends.” (16-Mother) “No, I feel it more (worse)... because this is not sorrow, it’s... just that it leaves you empty, a very big void... there is sorrow here, there is no satisfaction... a very big sorrow in your soul.” (17-Mother) |

| Ambiguous loss | “I didn’t experience it that way. Although it is as though he had been taken away from me. After the vaccinations, he stopped looking at me, talking to me... everything. Before, he used to do it.” (03-Mother) “No, the feeling is that your son is never going to talk to you. It’s a weird feeling, I haven’t experienced anything similar, but it’s not comparable to the loss of a loved one.” (15-Father) |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bravo-Benítez, J.; Pérez-Marfil, M.N.; Román-Alegre, B.; Cruz-Quintana, F. Grief Experiences in Family Caregivers of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4821. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16234821

Bravo-Benítez J, Pérez-Marfil MN, Román-Alegre B, Cruz-Quintana F. Grief Experiences in Family Caregivers of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(23):4821. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16234821

Chicago/Turabian StyleBravo-Benítez, Jorge, María Nieves Pérez-Marfil, Belén Román-Alegre, and Francisco Cruz-Quintana. 2019. "Grief Experiences in Family Caregivers of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 23: 4821. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16234821

APA StyleBravo-Benítez, J., Pérez-Marfil, M. N., Román-Alegre, B., & Cruz-Quintana, F. (2019). Grief Experiences in Family Caregivers of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(23), 4821. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16234821