Aspects of Illness and Death among Roma—Have They Changed after More than Two Hundred Years?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Samples

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Analyses and Reporting

2.4. Research Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Roma Illnesses and Death in the Late 18th Century

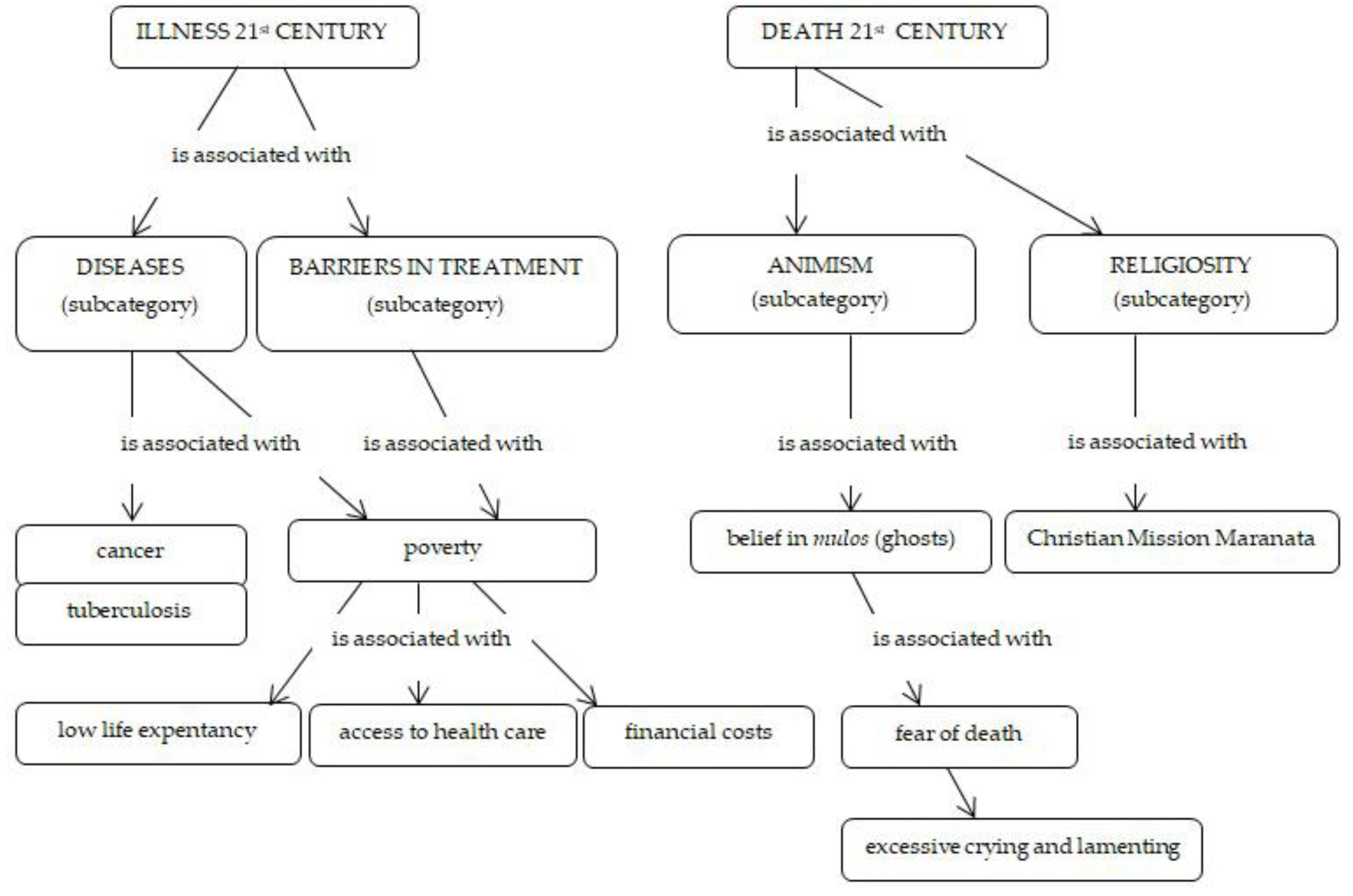

3.2. Roma Illnesses and Death in the 21st Century

4. Discussion

4.1. Illnesses

4.2. Death and Dying

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

4.4. Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Paralikas, T.; Kotrotsiou, S.; Kotrotsiou, E.; Gouva, M.; Hatzoglou, C.; Kavadias, D. Gypsies’s beliefs about the evil eye in relation to mental illness. Eur. Psychiatry 2017, 41, S517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Campayo, J.; Alda, M. Illness behavior and cultural characteristics of the Gypsy population in Spain. Actas Esp. Psiquiatr. 2007, 35, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pavlic, D.R.; Zelko, E.; Kersnik, J.; Lolic, J. Health beliefs and practices among Slovenian Roma and their response to febrile illnesses: A qualitative study. Zdr. Varst. 2011, 50, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Roma, G.; Gramma, R.; Enache, A.; Parvu, A.; Ioan, B.; Moisa, S.M.; Dumitras, S.; Chirita, R. Dying and death in some Roma communities: Ethical challenges. J. Immigr. Minority Health 2014, 16, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, G.; Tighe, B. Gypsy Culture and Health Care. Am. J. Nurs. 1973, 73, 282–285. [Google Scholar]

- Dion, X. Gypsies and Travellers: Cultural influences on health. Community Pract. 2008, 81, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Goward, P.; Repper, J.; Appleton, L.; Hagan, T. Crossing boundaries. Identifying and meeting the mental health needs of Gypsies and Travellers. J. Ment. Health 2006, 15, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaric-Juric, T.; Klaric, I.M.; Narancic, N.S.; Drmic, S.; Salihovic, M.P.; Lauc, L.B.; Milicic, J.; Barabalic, M.; Zajc, M.; Janicijevic, B. Trapped between tradition and transition: An anthropological and epidemiological cross-sectional study of Bayash Roma in Croatia. Croat. Med. J. 2007, 48, 708–719. [Google Scholar]

- Belak, A. Zdravie Očami Vylúčených: Medicínsko-Antropologická Štúdia Stredoslovenskej Rómskej Osady (Health through the Eyes of the Excluded: A Medical-Anthropological Study of a Segregated Roma Settlement in Central Slovakia); Charles University: Prague, Czechia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Belak, A. Segregovani Romovia a zdravotne politiky: Eticke a prakticke rozpory (Segregated Roma and health policies: Ethical and practical contradictions). In Cierno-Biele Svety Romovia v Majoritnej Spoločnosti na Slovensku; Podolinska, T., Hrustic, T., Eds.; VEDA Ustav Etnologie Slovenskej Akademie vied: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zadravec, J. Health Culture of the Roma People in Prekmurje; Pomurska Založba: Murska Sobota, Slovenia, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Rotar Pavlič, D.; Zelko, E.; Kersnik, J.; Lolić, V. Health beliefs and practices among Slovenian Roma and their response to febrile illnesses: A qualitative study. Slov. J. Public Health 2011, 50, 169–174. [Google Scholar]

- Zeman, C.L.; Depken, D.E.; Senchina, D.S. Roma health issues: A review of the literature and discussion. Ethn. Health 2003, 8, 223–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cleemput, P.; Parry, G.; Thomas, K.; Peters, J.; Cooper, C. Health-related beliefs and experiences of gypsies and travelers: A qualitative study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2007, 61, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vivian, C.; Dundes, L. The Crossroads of Culture and Health among the Roma (Gypsies). J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2004, 36, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belak, A.; Madarasova Geckova, A.; Reijneveld, S.A.; van Dijk, J.P. Why do segregated Roma not do more for their health? An explanatory framework from an ethnographic study in Slovakia. Int. J. Public Health 2018, 63, 1123–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidova, E. Kvalita Zivota a Socialni Determinanty Zdravi u Romu v Ceske a Slovenske Republice; Triton: Prague, Czechia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Traykova, G.; Tabanska-Petkova, M.; Tzacheva, N. Management of the most common diseases among Roma population. Eur. J. Public Health 2016, 26 (Suppl. S1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Belak, A.; Veselska, Z.D.; Geckova, A.M.; van Dijk, J.P.; Reijneveld, S.A. How well do health-mediation programs address the determinants of the poor health status of Roma? A longitudinal case study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolvek, G.; Rosicova, K.; Rosenberger, J.; Podracka, L.; Stewart, R.E.; Nagyova, I.; Reijneveld, S.A.; van Dijk, J.P. End-stage renal disease among Roma and non-Roma: Roma are at risk. Int. J. Public Health 2012, 57, 751–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolvek, G.; Podracka, L.; Rosenberger, J.; Stewart, R.E.; van Dijk, J.P.; Reijneveld, S.A. Kidney diseases in Roma and non-Roma children in eastern Slovakia: Are Roma children more at risk? Int. J. Public Health 2014, 59, 1023–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolvek, G.; Straussova, Z.; Majernikova, M.; Rosenberger, J.; van Dijk, J.P. Health Differences between Roma and Non-Roma in the Slovak Dialyzed Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrikova, J.; Janicko, M.; Fedacko, J.; Drazilova, S.; Geckova, A.M.; Marekova, M.; Pella, D.; Jarcuska, P. Serum Uric Acid in Roma and Non-Roma—Its correlation with Metabolic Syndrome and other variables. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drazilova, S.; Janicko, M.; Kristian, P.; Schreter, I.; Halanova, M.; Urbancikova, I.; Geckova, A.M.; Marekova, M.; Pella, D.; Jarcuska, P.; et al. Prevalence and risk factors for Hepatitis B Virus infection in Roma and Non-Roma people in Slovakia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halanova, M.; Veseliny, E.; Kalinova, Z.; Jarcuska, P.; Janicko, M.; Urbancikova, I.; Pella, D.; Drazilova, S.; Babinska, I.; Team, H. Seroprevalence of Hepatitis E Virus in Roma settlements: A comparison with the general population in Slovakia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antolova, D.; Janicko, M.; Halanova, M.; Jarcuska, P.; Geckova, A.M.; Babinska, I.; Kalinova, Z.; Pella, D.; Marekova, M.; Veseliny, E.; et al. Exposure to Toxoplasma gondii in the Roma and Non-Roma inhabitants of Slovakia: A cross-sectional seroprevalence study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozubik, M.; Van Dijk, J.P.; Odraskova, B. Roma Housing and Eating in 1775 and 2013: A Comparison. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lackova, E. Ľudové Liečenie Olašských Rómov Východného Slovenska v Minulosti. (Vlachiko Roma Folk Medicine in Eastern Slovakia in the Past). In Slovenský Národopis; Slovak Academy of Science: Bratislava, Slovakia, 1988; Volume 36, pp. 203–208. [Google Scholar]

- Davidova, E. Bez Kolíb a Šiatrov (Without Huts and Tents); Východoslovenské Vydavateľstvo (Slovak): Košice, Slovakia, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, A.B. Obyčaje pri Úmrtí Cigánov-Rómov v Troch Spišských Obciach. (Customs related to Dying of Gypsy-Roma in three Spiš Villages). In Slovenský Národopis; Slovak Academy of Science: Bratislava, Slovakia, 1988; Volume 36, pp. 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Augustiniab Hortis, S. Von dem Heutigen Zustände, Sonderbaren Sitten und Lebensart, Wie Auch von Denen Übrigen Eigenschaften und Umständen der Zigeuner in Ungarn. (Translation: Urbancová, V. 1994); (On the Present Situation, Special Manners and Way of Life, as Well as Other Characteristics and Circumstances of the Gypsies in Hungary); Kaiserliche Königliche Allergnädigste Privilegierte Anzeigen aus Sämstlichen Kaiserl. Königl. Erbländer: Wien, NY, USA, 1776; Volume 1775, pp. 20–44. [Google Scholar]

- Urbancova, V. Cigáni v Uhorsku. Zigeuner in Ungarn; (Gypsies in Hungary); Studio DD: Bratislava, Slovakia, 1994; (In Bilingual Slovak and German). [Google Scholar]

- Soukup, V. Přehled Antropologických Teorií Kultury (Survey of Anthropological Theories of Culture); Portál: Praha, Czechia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, C. The Interpretation of the Cultures; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, C. Work and Lives: The Anthropologist as an Author; Stanford University Press: Stanford, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Rosinsky, R. Amare Roma (Our Roma); Constantine the Philosopher University: Nitra, Slovakia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kozubik, M. (Ne) Vinní a Dilino Gadžo ((Un) Guilty and Dumb White); Constantine the Philosopher University: Nitra, Slovakia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Atlas Rómskych Komunít na Slovensku 2019 (Atlas of Roma Communities in Slovakia 2019); USVpRK: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2019; Available online: https://www.minv.sk/?atlas-romskych-komunit-2019 (accessed on 2 October 2019).

- Weber, M. The Meaning of Ethnical Neutrality in Sociology and Economics. In Max Weber on the Methodology of Social Sciences; Shils, E., Finch, H., Eds.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, M. Die Protestantische Ethik und der Geist des Kapitalismus (The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism); Mohr: Tübingen, Germany, 1920. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, M. Zur Geschichte der Handelsgesellschaften im Mittelalter (History of Commercial Companies in the Middle Ages); Mohr: Stuttgart, Germany, 1889. [Google Scholar]

- Major, R.H. A History of Medicine; Springfield (Ill) Oxford: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Horvathova, E. Cigáni na Slovensku (Gypsies in Slovakia); Slovak Academy of Science (Slovak): Bratislava, Slovakia, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Zdravé Komunity. Healthy Communities. Available online: http://zdraveregiony.eu/poslanie-a-ciele/ (accessed on 26 August 2018).

- Podolinska, T.; Hrustic, T. Boh Medzi Bariérami. Sociálna Inklúzia Rómov Náboženskou Cestou (God between Barriers. Social Inclusion of Roma through Religion); Institute of Ethnology, Slovak Academy of Science: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2010. (In Slovak) [Google Scholar]

- Molinuevo, D.; Koomen, M.; Fóti, K. Living Conditions of the Roma: Substandard Housing and Health; European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions: Dublin, Ireland, 2012; Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/sites/default/files/ef_publication/field_ef_document/ef1202en.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2018).

- Pappa, E.; Chatzikonstantinidou, S.; Chalkiopoulos, G.; Papadopoulos, A.; Niakas, D. Health-Related Quality of Life of the Roma in Greece: The Role of Socio-Economic Characteristics and Housing Conditions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 6669–6681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Six, J.; Lorez, M.; Galli, F.; Arndt, V. Age-dependent risk and lifetime risk of developing cancer in Switzerland. Schweiz. Krebsbulletin 2017, 3, 284–291. [Google Scholar]

- Vilinova, K.; Repaska, G.; Vojtek, M.; Dubcova, A. Spatio-Temporal Differentiation of Cancer Incidence in Slovakia. Eur. Spat. Res. Policy 2017, 24, 167–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fundación Secretariado Gitano. Zdravotná Starostlivosť v Sociálne Vylúčených Rómskych Komunitách (Health Care in Socially Excluded Roma Communities); FSG: Madrid, Spain, 2007; Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_projects/2004/action3/docs/2004_3_01_manuals_sk.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2017). (In Slovak)

- Infostat. Prognóza Vývoja Obyvateľstva Podľa Okresov v SR Do Roku 2025; (Prognosis of Population Development by Districts in the Slovak Republic till 2015); Infostat: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2008; Available online: http://www.infostat.sk/vdc/pdf/publikaciaproj.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2017). (In Slovak)

- Liegeois, J.P. Roma, Gypsies, Travellers; Council of Europe: Strassbourg, France, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Rosinsky, R. Etnické Postoje Učiteľov, Študentov a Žiakov I. Stupňa ZŠ (s Akcentom na Rómsku Etnickú Skupinu) (Ethnic Attitudes of Teachers, Students and Pupils in Stage I at Elementary Schools (with Focus on the Roma Ethnic Group); UKF: Nitra, Slovakia, 2009. (In Slovak) [Google Scholar]

- Lamber, S.C.; Loiselle, C.G. Combining Individual Interviews and Focus Groups to Enhance Data Richness. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molzahn, A.E.; Starzomski, R.; McDonald, M.; O’Loughlin, C. Chinese Beliefs towards Organ Donation. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strategy of Slovak Republic for Roma Integration till 2020; (Stratégia Slovenskej Republiky pre Integráciu Rómov do Roku 2020); National Council of the Slovak Republic: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2012.

- Trofimova, K. Transforming Islam among Roma communities in the Balkans: A case of popular religiosity. Natl. Pap. J. Natl. Ethn. 2017, 45, 598–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakoubek, M.; Budilova, L. Structural analysis of Roma religiosity based on the ritual practice of “Oath at the Cross”. Hist. Sociol. 2014, 1, 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- International Federation of Social Workers (IFSW): Global Definition of Social Work. Available online: https://www.ifsw.org/what-is-social-work/global-definition-of-social-work/ (accessed on 25 September 2018). (In English).

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kozubik, M.; van Dijk, J.P.; Filakovska Bobakova, D. Aspects of Illness and Death among Roma—Have They Changed after More than Two Hundred Years? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4796. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16234796

Kozubik M, van Dijk JP, Filakovska Bobakova D. Aspects of Illness and Death among Roma—Have They Changed after More than Two Hundred Years? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(23):4796. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16234796

Chicago/Turabian StyleKozubik, Michal, Jitse P. van Dijk, and Daniela Filakovska Bobakova. 2019. "Aspects of Illness and Death among Roma—Have They Changed after More than Two Hundred Years?" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 23: 4796. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16234796

APA StyleKozubik, M., van Dijk, J. P., & Filakovska Bobakova, D. (2019). Aspects of Illness and Death among Roma—Have They Changed after More than Two Hundred Years? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(23), 4796. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16234796