“Language Breathes Life”—Barngarla Community Perspectives on the Wellbeing Impacts of Reclaiming a Dormant Australian Aboriginal Language

Abstract

:1. Introduction

“Indigenous peoples have the right to revitalize, use, develop and transmit to future generations their histories, languages, oral traditions, philosophies, writing systems and literatures…”

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Decolonising Methodologies

“Indigenous methodologies make visible within the research process what is meaningful and logical in Indigenous understandings of ourselves and the world [27]. An Indigenous methodology, therefore, is a methodology where the approach to, and undertaking of, research process and practices take Indigenous worldviews, perspectives, values and lived experience as their central axis” [26].

2.2. Aboriginal Governance and Leadership

2.3. Ethics

2.4. Study Design

2.5. Community Engagement and Development of Research Questions

2.6. Procedures

2.7. Analysis and Interpretation

2.8. Feedback and Consensus

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Themes

3.2.1. Connection to Spirit, Spirituality and Ancestors

“Language breathes life. Like we talked about breathing life back into the land, and it’s that ancient language.”

“And it’s that spirit of the land, of their heritage, their culture, their people that are going, ‘We’re not going to let you forget who you are and where you’re from.’ And when you’re having a moment of, despair or depression or—you know, I’ve seen people go right down to the bottom. […] And it’s been their heritage, and culture, and their identity bring them back. Bring them back and ground them to who they are and where they’re from.”

“If they were alive today, people that have passed away, they would have loved to be here. And that’s where, sometimes I’ll drive along, and I’ll smile to myself about words [a departed Elder] always used to say—and then when I’m going and doing something, I smile because it’s like, ‘We’re doing it now’, you know what I mean? And he’s looking down. This is what he wanted, everything to be Barngarla and Barngarla to be recognised. So even though they’re not here, it’s about honouring their legacy that they started and that they wanted to finish.”

3.2.2. Connection to Country

“I think [Barngarla language] has been the final thing to bring back spirit into land. Because people went, and they connected, and wanted to learn that ceremony, and wanted to learn them stories and all. But it all comes back to song. It all comes back to words. It comes back to putting that spirit back into Country through song.”

“When we are talking inside, it’s just us talking. When you’re talking outside, you’re breathing language into the land and into the sea and into the air and into the birds and into the fish and into the trees and you’re awakening that with all that spirit. You’re speaking life into all our ancient spirits out there and they’re sitting around listening.”

3.2.3. Connection to Culture

“I think it’s very important that we, as Barngarla people, get to learn what’s us, what makes us, us. And that’s our language and that’s our culture and that’s our Dreaming. Those three there are interconnected with who we are as Aboriginal people.”

“So, I think your heritage and culture, and your identity, is something that—especially nowadays when people struggle with their health and wellbeing—the power of who you are and where you come from, and just the resilience that your people went through in maintaining their heritage, their culture, just in fighting to still be alive today is so powerful. So there’s a lot of strength that comes through so many generations.”

“I had my sisters and brothers around me but there was something missing. And that was being able to communicate properly with them. On face-to-face language, and I didn’t have a language. All I had was English.”

“Being an Aboriginal person, culture is the main thing. […] If you can’t speak your own language, there’s that piece missing. And when you can speak your own language, learn it there, you live in your culture, you’re speaking your culture’s language, everything learnt there, all come together, it’s the missing part of the jigsaw puzzle. […] You are getting that empowerment to speak your own language. It feels good, like lifting a burden off your side, like something is missing from a jigsaw puzzle. It’s that little puzzle piece missing, and it’s finally getting put back there, feel complete then.”

“With learning my language, it’s like I’ve learned another part of me. I can tell you now that before I learned that I had a language, I knew that I was Aboriginal, but I didn’t know which tribe or anything. And once I learned that I was Barngarla, and my language, it was like my other half came in. I don’t really know how to explain it. It was like a sense of who you are, a sense of wellbeing.”

“With all my mother, my uncles and aunties all being taken away, they missed out on all of those songs. That was their birthright. That was something they should have [had] as young children growing up with their grandparents or whoever. And they missed out. So, to be able to collect that and be able to give that back to the next generation, I think is—it’s awesome.”

“It’s an obligation to me, it’s an obligation to every Barngarla person to make sure that we [reclaim] what we didn’t have.”

“The reason why we want keep on doing it is because we want our children to learn, our grandchildren to learn. I want to learn myself because that’s my language and I feel like I’ve got to learn it first before my kids and my grandkids, you know what I mean? But, I’m really happy that we’re all doing it together as a family. That’s the best thing about it, that I’m doing it with my children, I’m sharing it with my children, and my grandchildren.”

“Or we could be going down the beach and she’ll say, ‘What’s the Barngarla word for this, Mum, and what’s the Barngarla for that?’ So I need to learn it because they [young kids] are just thirsty for it. They want it, you know. […] And they really come out with things that make you go, ‘Wow! They are paying attention!’ And they are going to be so strong in it. And you don’t realise but, from that young age, that’s where it does all come along, and filters down. And they just gain their strength from it.”

“Everyone knows nursery rhymes and things from when they were kids and you never forget it. If we had Barngarla songs like that, that we could sing to our kids, our grandkids when they’re going to bed or whatever, you know, that will be imprinted into their brain and that will be forever. […] So, you’re singing these to the children every day, every night and it’s just going to be imprinted, it’s going to be there, and they’ll never get rid of it. They’ll sing that to their children and they’ll sing it to their children. And it’ll just go on forever hopefully.”

3.2.4. Connection to Family and Kinship

“I think the thing that sort of helped the family come together and start reconnecting with language, heritage and culture was really powerful. Because it started to show them, regardless of what’s happened [when they were removed], ‘You come from this long line of strong people. And your spirit is resilient. You came home. You came home to family. Your next generation—you need to be able to talk through what you went through, so they can understand.’”

“It’s also enjoyable and you get to speak to other family members who you don’t normally see. Usually the only time us blackfellas get together is like funerals, you know. So, it’s another way of us getting together and being able to enjoy what we have, and that’s the Barngarla language.”

“Interacting with the family members there, as they help each other with the painting styles, and listen to each other’s stories, tell each other stories. So, it’s good to see. And not only that, the younger generation is involved in it too. So, you have the grandmothers, you have the mothers, you have the sons, niece, grandchildren, all mixing, and you don’t sort of see that that much these days, you know, and it’s good to actually see it.”

“The languages have an impact on that as well because there’s this continual gathering. We’re starting to gather now, and we’re not sort of scattered. I’d say that has had an impact.”

“It brings me back and into that family circle and I can walk along with them now and not sort of on that outside. So, it brings me back in and it gives me a sense of belonging again, if you can say that, and looking forward to something that’s going to help the family, going to help the group, the tribal group and the generations to come. […] It brings a sense of belonging again and community and being able to achieve something together instead of separately. It’s bringing us together.”

“The language and the language programs have brought us together. As well, I guess being in my land and surrounded by my family and learning my language has made me a lot happier.”

3.2.5. Connection to Community

“I felt what I was doing was just out there sharing my heritage and culture, as well as bridging the gap between Aboriginal [people] and the wider community. […] I was just bridging the gap between everyone.”

“So, working in the wider community, you have to work in both worlds. You can’t exclude yourself and just be all about Aboriginal people. Because we live in a society where we have to bring it forward. It’s the only way that we’re going to make it work and sustain it. […] And it’s good. Because it shows that we have influenced change here. These are people that want to acknowledge that they are on your traditional lands, and they want to meet you. Because they see you around, they see your kids around. […] And I believe the wider community’s interested in that as well, you know, the language and what we call things.”

“Things have shifted, people’s negativity has shifted. There is a lot of good spirit work happening here, and a lot of people feeling that now. […] They look at us and how happy we are just doing our heritage, our culture and our language.”

“We’ve always seen Barngarla language as a sort of reconciliation tool. And that’s why, when we talk about taking it into the schools—majority of those kids are going to be non-Aboriginal. So, we’re only going to get a small handful that are Aboriginal, and an even smaller handful that are Barngarla. So, when we talk about wanting to expose the school kids to that, I think it does go towards reconciliation, because they’re going to start from a young age, learning about us and our language and our culture and what we’re trying to do. And, yeah, I think that would impact on the whole community.”

3.2.6. Connection to Mind and Emotions

“Everyone’s a bit more pepped up these days, you know. After going to that many meetings and all that and being told where you’re from, everything’s starting to go in the right direction. Language is coming back.”

“You see them when they come back with—got a recharge, got a bit of spark, like a bit of a twinkle in the eye and a sort of upbeat lift. After learning a few more words and all that there, it feels like they come back real pumped, excited. So, to me, when you get excited about something you’re doing, it’s doing good for you.”

“You’re looking at us and seeing us happy, and it’s because we’re genuinely happy. You know, when we’re learning our language and talking it. It is coming from a place where it’s making you happy.”

“At present we still don’t speak our own language. It’s difficult to be able to just open up. I would love to be able to speak to my family in my language and let them know how I feel about them. But I don’t want to talk like that in English, I’d rather talk in my language and let them know how much I love them.”

“Because it not only allowed us to empower and teach our young fellas, but it got to the community that it wasn’t us butting heads. It’s about the next generation being who they are, and where they’re from, and embracing their heritage, their culture, and using their language.”

“Probably the most important thing that I’ve learnt—health-wise—is probably looking after myself more, probably greeting people with a different attitude. Trying to be positive, you know. So, language has done a lot for me although I still don’t know how to speak it.”

“I do look forward to when the language groups are on. Because I can get out and mix with people and, not just with my family group but meeting new people that come. And it just opens you up to be able to share what you have inside you and what you hope, and your thoughts – and it takes you out of your comfort zone too. So that’s the way it’s sort of helped me. I just get up and it’s motivating.”

3.2.7. Connection to Self

“Language plays probably the most important part I believe, in me being who I am and my family being who they are. […] Not [just] learning it but how powerful it is to make you who you are.”

“For me to actually learn about my language and my culture, and my heritage and everything, I reckon it’s just given me the courage; gave me more courage and gave me pride to look at me and think, “I know who I am.” I know my language. Even if I’m not fluent, I can still learn it. And I know just, who I am, and who my ancestors are, and where our boundaries are, and my culture. And I’d love to learn more about it. And I just feel real proud to be who I am.”

“I don’t know how to explain it. It’s like a joyful feeling. Because I’m sharing the language […] And me speaking the language, like my ancestors before me, it’s like a step closer to—I don’t know how to say it. It’s like an overwhelming feeling of happiness and pride in being who I am, and being a Barngarla descendent.”

4. Discussion

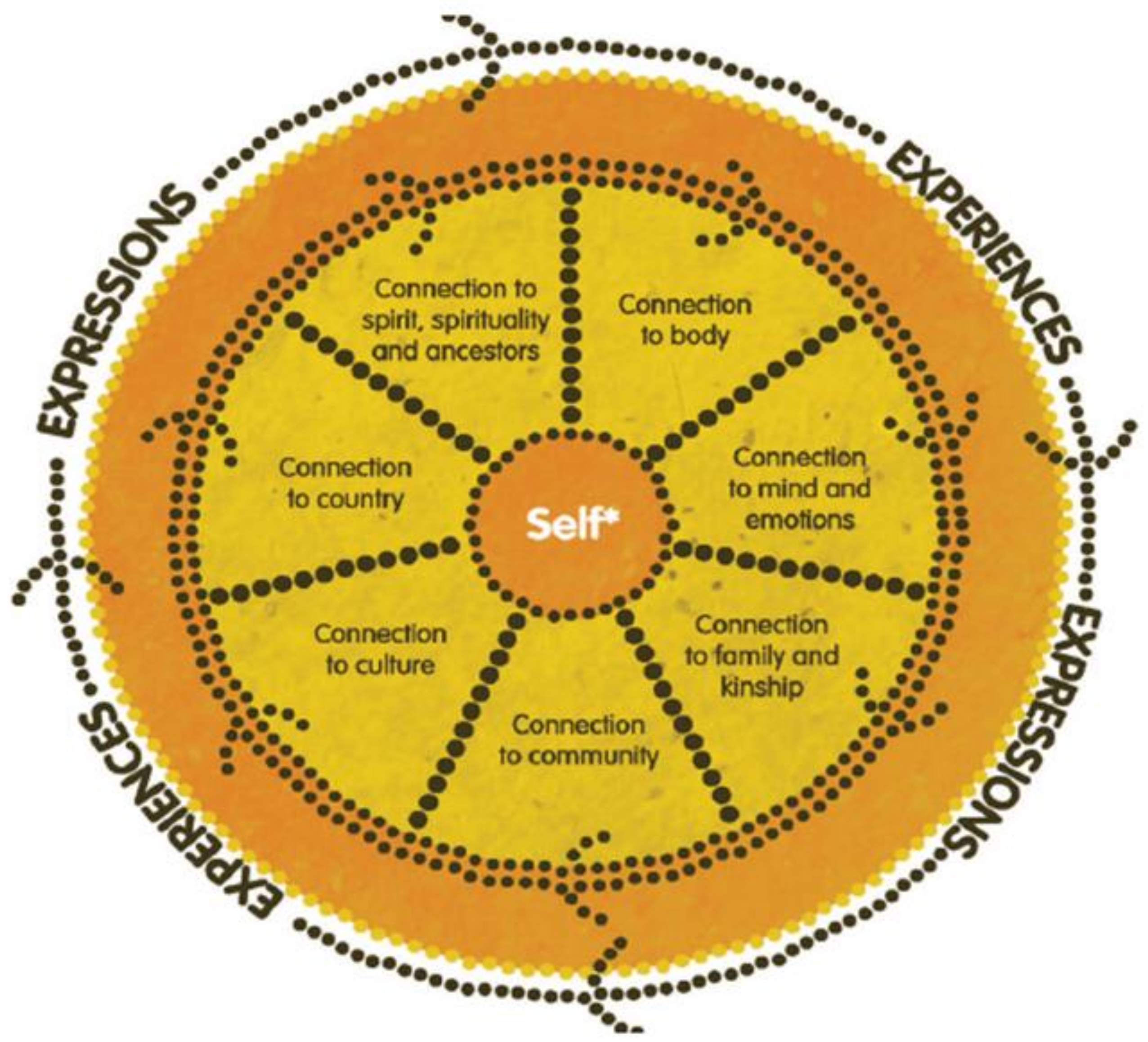

4.1. Aboriginal Social and Emotional Wellbeing

“Aboriginal health means not just the physical well-being of an individual but refers to the social, emotional and cultural well-being of the whole Community in which each individual is able to achieve their full potential as a human being thereby bringing about the total well-being of their Community. It is a whole of life view and includes the cyclical concept of life-death-life.”

4.2. Intergenerational Transfer of Knowledge

4.3. Language Reclamation and Wellbeing

4.4. Community Impacts of Language Reclamation

4.5. Research Benefit

4.6. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. United Nations: State of the World’s Indigenous Peoples ST/ESA/328; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. United Nations: United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples: Resolution/Adopted by General Assembly, 2 October 2007, A/RES/61/29; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Marmion, D.; Obata, K.; Troy, J. Community, Identity, Wellbeing: The Report of the Second National Indigenous Languages Survey; Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies: Canberra, Australia, 2014.

- Zuckermann, G.; Shakuto-Neoh, S.; Quer, G.M. Native Tongue Title: Compensation for the loss of Aboriginal languages. Aust. Aborig. Stud. 2014, 2014, 55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood, J. Colonisation-it’s bad for your health: The context of Aboriginal health. Contemp. Nurse 2013, 46, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, A.; Gillies, M.; Howard, P.J.; Coffin, J. It’s enough to make you sick: The impact of racism on the health of Aboriginal Australians. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2007, 31, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swan, P.; Raphael, B. Ways Forward: National Consultancy Report on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health; Australin Government Publishing Service: Canberra, Australia, 1995.

- National Aboriginal Health Strategy Working Party. The National Aboriginal Health Strategy; National Aboriginal Health Strategy Working Party: Canberra, Australia, 1989.

- Hallett, D.; Chandler, M.J.; Lalonde, C.E. Aboriginal language knowledge and youth suicide. Cogn. Dev. 2007, 22, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubrick, S.; Silburn, S.; Lawrence, D.; Mitrou, F.; Dalby, R.; Blair, E.; Griffin, J.; Milroy, H.; De Maio, J.; Cox, A.; et al. The Western Australian Aboriginal Child Health Survey: The Social and Emotional Wellbeing of Aboriginal Children and Young People; Curtin University of Technogoly: Perth, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages. Global Language Hotspots; Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages: Salem, OR, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Census of Population and Housing: Characteristics of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians 2016; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2018.

- Burdon, A. Speaking Up. Australian Geographic. Available online: https://www.australiangeographic.com.au/topics/history-culture/2016/04/speaking-up-australian-aboriginal-languages/ (accessed on 14 October 2019).

- Biddle, N.; Swee, H. The Relationship between Wellbeing and Indigenous Land, Language and Culture in Australia. Aust. Geogr. 2012, 43, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, K.G.; O’Dea, K.; Anderson, I.; McDermott, R.; Karmananda, S.; Tilmouth, R.; Roberts, I.; Fitz, J.; Wang, Z.; Jenkins, A.; et al. Lower than expected morbidity and mortality for an Australian Aboriginal population: 10-year follow-up in a decentralised community. Med. J. Aust. 2008, 188, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuckermann, G.; Walsh, M. “Our Ancestors Are Happy!” Revivalistics in the service of Indigenous wellbeing. In Proceedings of the 18th Foundation for Endangered Languages Conference, Okinawa, Japan, 17–20 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sivak, L.; Westhead, S.; Richards, E.; Atkinson, S.; Dare, H.; Richards, J.; Zuckermann, G.; Rosen, A.; Gee, G.; Wright, M.; et al. Can the revival of Indigenous languages improve the mental health and social and emotional wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people? Symposium presentation. In Proceedings of the 28th TheMHS Conference, Adelaide, Australia, 28 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Moreton-Robinson, A. Critical Indigenous Studies: Engagements in First World Locations; The University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chilisa, B.; Tsheko, G.N. Mixed Methods in Indigenous Research. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2014, 8, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruwhiu, D.; Cathro, V. ‘Eyes wide shut’ insights from indigenous research methodology. Emerg. Complex. Organ. 2014, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Tuhiwai Smith, L. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, 2nd ed.; Zed Books: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Doxtater, T.M. Healing historical unresolved grief: A decolonizing methodology for Indigenous language revitalization and survival. Action Learn. Action Res. Assoc. 2011, 17, 97–117. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, S. Research is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods; Fernwood Publishers: Halifax, NS, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S.; Tuhiwai Smith, L. Handbook of Critical and Indigenous Methodologies; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, R. Freeing ourselves from neo-colonial domination in research: A Maori approach to creating knowledge. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 1998, 11, 199–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, M.; Suina, M. Indigenous data, indigenous methodologies and indigenous data sovereignty. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2019, 22, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porsanger, J. An essay about Indigenous methodology. Nordlit 2004, 8, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.; Saggers, S.; Taylor, K.; Pearce, G.; Massey, P.; Bull, J.; Odo, T.; Thomas, J.; Billycan, R.; Judd, J.; et al. “Makes you proud to be black eh?”: Reflections on meaningful Indigenous research participation. Int. J. Equity Health 2012, 11, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, M. A review of the literature on the benefits and drawbacks of participatory action research. First Peoples Child Fam. Rev. 2004, 1, 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Chilisa, B. Indigenous Research Methodologies; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Davy, C.; Cass, A.; Brady, J.; DeVries, J.; Fewquandie, B.; Ingram, S.; Mentha, R.; Simon, P.; Rickards, B.; Togni, S.; et al. Facilitating engagement through strong relationships between primary healthcare and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2016, 40, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davy, C.; Kite, E.; Sivak, L.; Brown, A.; Ahmat, T.; Brahim, G.; Dowling, A.; Jacobson, S.; Kelly, T.; Kemp, K.; et al. Towards the development of a wellbeing model for aboriginal and Torres Strait islander peoples living with chronic disease. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mentha, R.A.; de Vries, J.; Simon, P.R.; Fewquandie, B.N.; Brady, J.; Ingram, S. Bringing our voices into the research world: Lessons from the Kanyini Vascular Collaboration. Med. J. Aust. 2012, 197, 55–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, M.; O’Brien, M.; Sivak, L.; Ahmat, T.; Brahim, G.; Brown, A.; Davy, C.; Dowling, A.; Jacobson, S.; Kelly, T.; et al. A ‘Wellbeing Framework’ for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples living with chronic disease. In Proceedings of the 13th National Rural Health Conference, Darwin, Australia, 24–27 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gee, G.; Dudgeon, P.; Schultz, C.; Hart, A.; Kelly, K. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social and Emotional Wellbeing. In Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Social and Emotional Wellbeing Principles and Practice; Dudgeon, P., Milroy, H., Walker, R., Eds.; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2014; pp. 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Mudrooroo. Us mob: History, Culture, Struggle: An Introduciton to Indigenous Australia; Angus and Robertson: Pymble, Australia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- NACCHO (National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation). Constitution for the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation; NACCHO: Canberra, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, G. Introducing Wiradjuri language in Parkes. In Re-Awakening Languages: Theory and Practice in the Revitalisation of Australia’s Indigenous languages; Hobson, J., Poetsch, S., Walsh, M., Eds.; Sydney University Press: Sydney, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A. Addressing cardiovascular inequalities among indigenous Australians. Glob. Cardiol. Sci. Pract. 2012, 2012, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudgeon, P.; Milroy, H.; Walker, R. Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sivak, L.; Westhead, S.; Richards, E.; Atkinson, S.; Richards, J.; Dare, H.; Zuckermann, G.; Gee, G.; Wright, M.; Rosen, A.; et al. “Language Breathes Life”—Barngarla Community Perspectives on the Wellbeing Impacts of Reclaiming a Dormant Australian Aboriginal Language. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3918. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16203918

Sivak L, Westhead S, Richards E, Atkinson S, Richards J, Dare H, Zuckermann G, Gee G, Wright M, Rosen A, et al. “Language Breathes Life”—Barngarla Community Perspectives on the Wellbeing Impacts of Reclaiming a Dormant Australian Aboriginal Language. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(20):3918. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16203918

Chicago/Turabian StyleSivak, Leda, Seth Westhead, Emmalene Richards, Stephen Atkinson, Jenna Richards, Harold Dare, Ghil’ad Zuckermann, Graham Gee, Michael Wright, Alan Rosen, and et al. 2019. "“Language Breathes Life”—Barngarla Community Perspectives on the Wellbeing Impacts of Reclaiming a Dormant Australian Aboriginal Language" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 20: 3918. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16203918

APA StyleSivak, L., Westhead, S., Richards, E., Atkinson, S., Richards, J., Dare, H., Zuckermann, G., Gee, G., Wright, M., Rosen, A., Walsh, M., Brown, N., & Brown, A. (2019). “Language Breathes Life”—Barngarla Community Perspectives on the Wellbeing Impacts of Reclaiming a Dormant Australian Aboriginal Language. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(20), 3918. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16203918