Effects of a Dementia Screening Program on Healthcare Utilization in South Korea: A Difference-In-Difference Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Outcome Variables

2.3. Statistical Analysis

- T: Treatment group, C: Control group, : pre-DSP (2007), : post-DSP (2009)

- : Healthcare utilization in the treatment group; : Healthcare utilization in the control group

- : intercept, : difference between treatment group and control group, : the time trend, i: person

- : the time-invariant difference in outcomes between the two groups

- : the combined effects of any unmeasured covariates that changed between the two periods but affected the outcomes the same way in both groups

- : true effect of treatment under the common trend assumption, = random error

2.4. Ethics

3. Results

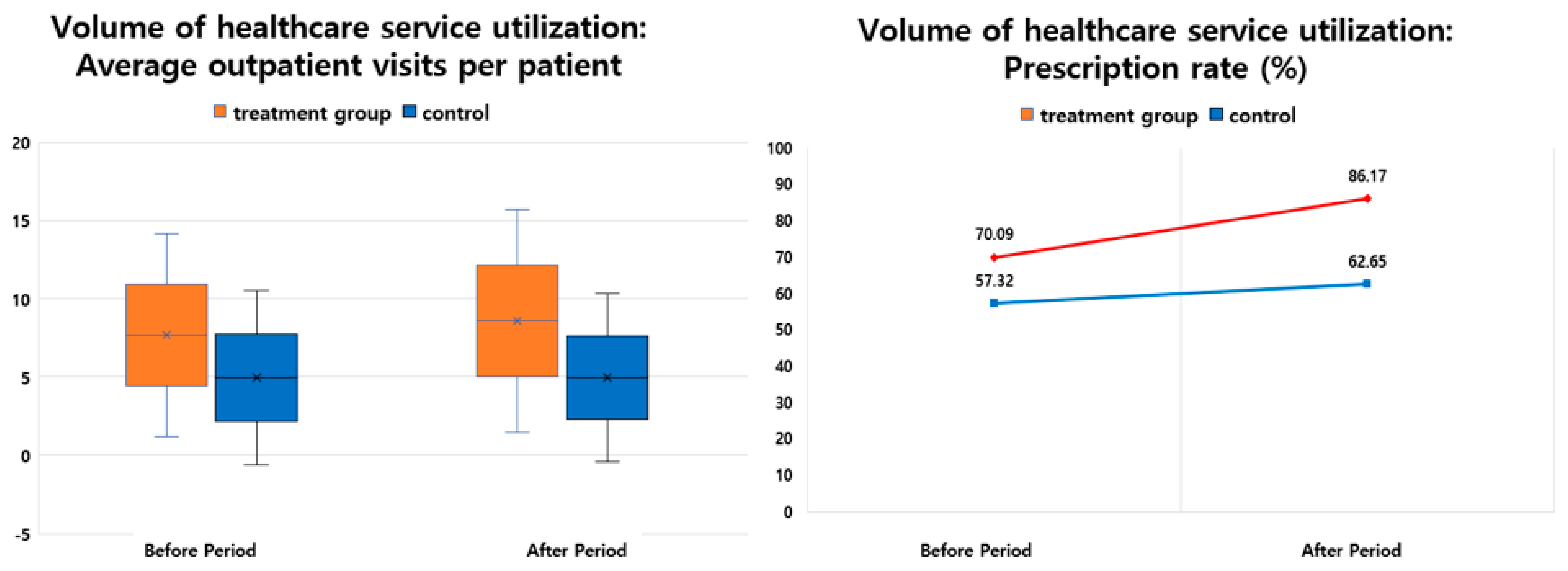

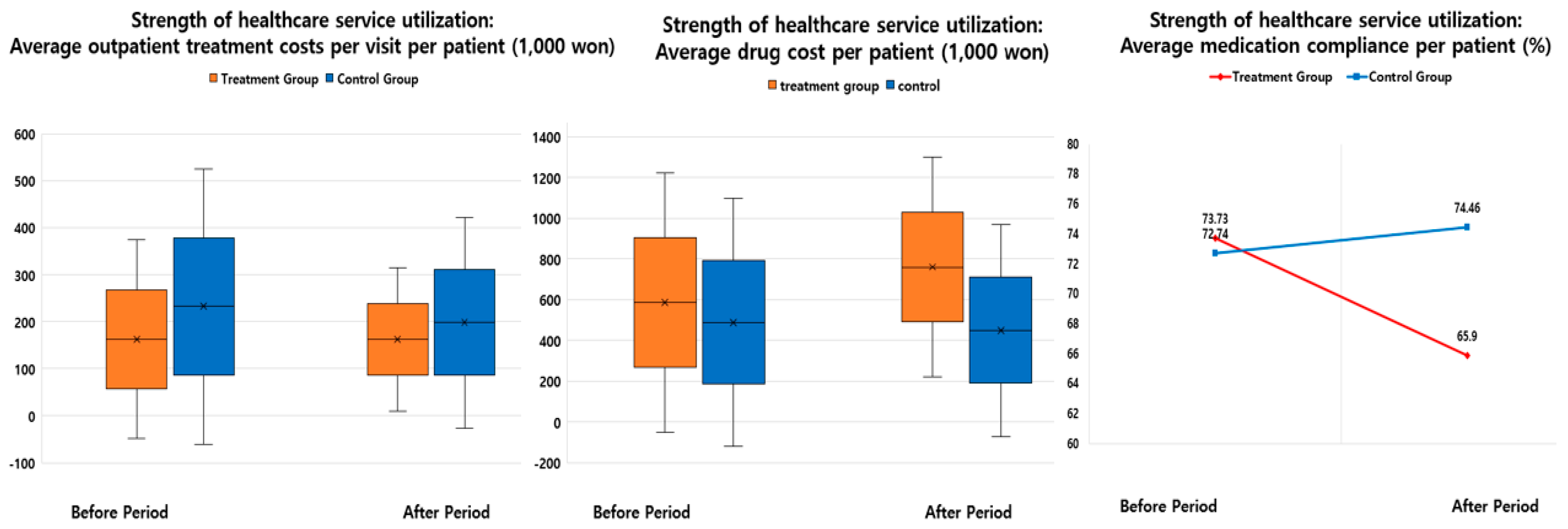

3.1. Differences in Healthcare Service Utilization before and after the Introduction of the DSP in the Treatment and Control Groups

3.2. Effects of the Introduction of the DSP on Healthcare Utilization

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mendez, M.F.; Cummings, J.L. Dementia: A Clinical Approach, 3rd ed.; Butterworth Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, S.; Kelly, S.; Khan, A.; Cullum, S.; Dening, T.; Rait, G.; Fox, C.; Katona, C.; Cosco, T.; Brayne, C.; et al. Attitudes and preferences towards screening for dementia: A systematic review of the literature. BMC Geriatr. 2015, 15, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korean National Statistical Office. 2018 Statistics on the Aged. Available online: http://www.kostat.go.kr/portal/korea/kor_nw/3/index.board?bmode=read&aSeq=370781&pageNo=1&rowNum=10&amSeq=&sTarget=title&sTxt=0 (accessed on 13 June 2019).

- Nam, H.J.; Hwang, S.H.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, K.W. Korea Dementia Observatory 2018; Ministry of Health and Welfare & National Institute of Dementia: Sungnam, Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jacqmin-Gadda, H.; Alperovitch, A.; Montlahuc, C.; Commenges, D.; Leffondre, K.; Dufouil, C.; Elbaz, A.; Tzourio, C.; Ménard, J.; Dartigues, J.-F.; et al. 20-Year prevalence projections for dementia and impact of preventive policy about risk factors. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 28, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.; Gwak, K.; Kim, B.; Kim, B.; Kim, J.; Kim, T.; Moon, S.; Park, K.; Park, J.; Park, J.; et al. Nationwide Survey on the Dementia Epidemiology of Korea; Ministry of Health and Welfare & National Institute of Dementia: Sungnam, Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, P.S.; Tang, J.S.; Chen, C.Y. An evaluation study of a dementia screening program in Taiwan: An application of the theory of planned behaviors. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2012, 55, 626–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prince, M.; Bryce, R.; Ferri, C. World Alzheimer Report 2011: The Benefits of Early Diagnosis and Intervention; Alzheimer’s Disease International: London, UK, 2011; Available online: http://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2011ExecutiveSummary.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2019).

- Bradford, A.; Kunik, M.E.; Schulz, P.; Williams, S.P.; Singh, H. Missed and delayed diagnosis of dementia in primary care. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2009, 23, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashford, J.W.; Borson, S.; O’Hara, R.; Dash, P.; Frank, L.; Robert, P.; Shankle, W.R.; Tierney, M.C.; Brodaty, H.; Schmitt, F.A.; et al. Should older adults be screened for dementia? It is important to screen for evidence of dementia! Alzheimer’s Dement. 2007, 3, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jungwirth, S.; Zehetmayer, S.; Bauer, P.; Weissgram, S.; Tragl, K.H.; Fischer, P. Screening for Alzheimer’s dementia at age 78 with short psychometric instruments. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2009, 21, 548–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodaty, H.; Connors, M.; Pond, D.; Cumming, A.; Creasey, H. Dementia: 14 essentials of assessment and care planning. Med. Today 2013, 14, 18–27. [Google Scholar]

- Brodaty, H.; Connors, M.; Pond, D.; Cumming, A.; Creasey, H. Dementia: 14 essentials of management. Med. Today 2013, 14, 29–41. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, N.R.; Boustani, M.A.; Frame, A.; Perkins, A.J.; Monahan, P.; Gao, S.; Sachs, G.A.; Hendrie, H.C. Impact of patients’ perceptions on dementia screening in primary care. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2012, 60, 1037–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fowler, N.R.; Perkins, A.J.; Turchan, H.A.; Frame, A.; Monahan, P.; Gao, S.; Boustani, M.A. Older primary care patients’ attitudes and willingness to screen for dementia. J. Aging Res. 2015, 2015, 423265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). Clinical Practice Guidelines and Principles of Care for People with Dementia; National Health and Medical Research Council: Sydney, Australia, 2016.

- Moon, S.H.; Seo, H.J.; Lee, D.Y.; Kim, S.M.; Park, J.M. Associations among health insurance type, cardiovascular risk factors, and the risk of dementia: A prospective cohort study in Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seoul Metropolitan Government. 2018 Guide for Seoul Dementia Management Project. Available online: http://www.seouldementia.or.kr (accessed on 5 October 2019).

- Banerjee, S.; Wittenberg, R. Clinical and cost effectiveness of services for early diagnosis and intervention in dementia. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2009, 24, 748–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Getsios, D.; Blume, S.; Ishak, K.J.; MacLaine, G.; Hernández, L. An economic evaluation of early assessment for Alzheimer’s disease in the United Kingdom. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2012, 8, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weimer, D.L.; Sager, M.A. Early identification and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: Social and fiscal outcomes. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2009, 5, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.Y.; Lee, T.J.; Jang, S.H.; Han, J.W.; Kim, T.H.; Kim, K.W. Cost-effectiveness of nationwide opportunistic screening program for dementia in South Korea. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2015, 44, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service (HIRA). Healthcare System in Korea. Available online: https://www.hira.or.kr/eng/about/06/02/index.html (accessed on 15 September 2019).

- Kim, L.; Kim, J.A.; Kim, S. A guide for the utilization of Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service National Patient Samples. Epidemiol. Health 2014, 36, e2014008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, K.S.; Yoon, S.J.; Ahn, H.S.; Shin, H.W.; Yoon, Y.H.; Hwang, S.M.; Kyung, M.H. The Effect of the Cost Exemption Policy for Hospitalized Children under 6 Years Old on the Medical Utilization in Korea. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2008, 41, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wing, C.; Simon, K.; Bello-Gomez, R.A. Designing difference in difference studies: Best practices for public health policy research. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2018, 39, 453–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.; Kim, H.; Ahn, H.; Kim, Y.; Hwang, J.; Kim, B.; Nam, H.; Na, L.; Byun, E. Korea Dementia Observatory 2016; Ministry of Health and Welfare & National Institute of Dementia: Sungnam, Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Geldmacher, D.S.; Frolich, L.; Doody, R.S.; Erkinjuntti, T.; Vellas, B.; Jones, R.W. Realistic expectations for treatment success in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2006, 10, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fillit, H.M.; Doody, R.S.; Binaso, K.; Crooks, G.M.; Ferris, S.H.; Farlow, M.R.; Leifer, B.; Mills, C.; Minkoff, N.; Orland, B. Recommendations for best practices in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease in managed care. Am. J. Geriatr. Pharm. 2006, 4, S9–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Category | (a) | p-Value | |||||

| Treatment Group | Control Group | All Patients | ||||||

| (N = 107) | (N = 13,874) | (N = 13,981) | ||||||

| Mean (SD) or n (%) | Range | Mean (SD) or n (%) | Range | Mean (SD) or n (%) | Range | |||

| Age (years) | 75.22 (7.56) | 60–95 | 75.15 (7.65) | 60–109 | 75.15 (7.65) | 60–109 | 0.9154 (t) | |

| Age group (years) | 60–64 | 9 (8.41) | 1215 (8.76) | 1224 (8.75) | 0.9669 (c) | |||

| 65–69 | 15 (14.02) | 2261 (16.30) | 2276 (16.28) | |||||

| 70–74 | 25 (23.36) | 3074 (22.16) | 3099 (22.17) | |||||

| 75–79 | 24 (22.43) | 3181 (22.93) | 3205 (22.92) | |||||

| ≥80 | 34 (31.78) | 4143 (29.86) | 4177 (29.88) | |||||

| Sex | Male | 32 (29.91) | 4552 (32.81) | 4584 (32.79) | 0.5240 (c) | |||

| Female | 75 (70.09) | 9322 (67.19) | 9397 (67.21) | |||||

| Major diagnosis | Alzheimer’s disease | 83 (77.57) | 9248 (66.66) | 9331 (66.74) | 0.0208 (c) | |||

| Vascular dementia | 14 (13.08) | 1889 (13.62) | 1903 (13.61) | |||||

| Other dementia | 10 (9.35) | 2737(19.73) | 2747(19.65) | |||||

| Comorbidities | Hypertension | 16 (14.95) | 1305 (9.41) | 1321 (9.45) | NE | |||

| Diabetes | 4 (3.74) | 476 (3.43) | 480 (3.43) | |||||

| Depression | 16 (14.95) | 2270 (16.36) | 2286 (16.35) | |||||

| Stroke | 20 (18.69) | 1624 (11.71) | 1644 (11.76) | |||||

| Type of institution | General hospital | 52 (48.60) | 10,170 (73.30) | 10,222 (73.11) | <0.0001 (c) | |||

| Hospital | 28 (26.17) | 777 (5.60) | 805 (5.76) | |||||

| Clinic | 27 (25.23) | 2818 (20.31) | 2845 (20.35) | |||||

| Public health facility | 0 (0.00) | 109 (0.79) | 109 (0.78) | |||||

| Clinical department | Neurology | 56 (52.34) | 5729 (41.29) | 5785 (41.38) | 0.0718 (c) | |||

| Psychiatry | 37 (34.58) | 5187 (37.39) | 5224 (37.36) | |||||

| Internal medicine | 5 (4.67) | 958 (6.91) | 963 (6.89) | |||||

| General medicine | 6 (5.61) | 762 (5.49) | 768 (5.49) | |||||

| Others | 3 (2.80) | 1238 (8.92) | 1241 (8.88) | |||||

| Variables | Category | (b) | p-Value | |||||

| Treatment Group | Control Group | All Patients | ||||||

| (N = 253) | (N = 25,119) | (N = 25,372) | ||||||

| Mean (SD) or n (%) | Range | Mean (SD) or n (%) | Range | Mean (SD) or n (%) | Range | |||

| Age (years) | Mean (SD) | 76.49 (7.45) | 60–97 | 75.55 (7.72) | 60–110 | 75.56 (7.72) | 60–110 | 0.0557 (t) |

| Age group (years) | 60–64 | 13 (5.14) | 1996 (7.95) | 2009 (7.92) | 0.2484 (c) | |||

| 65–69 | 36 (14.23) | 3930 (15.65) | 3966 (15.63) | |||||

| 70–74 | 50 (19.76) | 5533 (22.03) | 5583 (22.00) | |||||

| 75–79 | 63 (24.90) | 5722 (22.78) | 5785 (22.80) | |||||

| ≥80 | 91 (35.97) | 7938 (31.60) | 8029 (31.65) | |||||

| Sex | Male | 73 (28.85) | 8210 (32.68) | 8283 (32.65) | 0.1960 (c) | |||

| Female | 180 (71.15) | 16,909 (67.32) | 17,089 (67.35) | |||||

| Major diagnosis | Alzheimer’s disease | 214 (84.58) | 15,676 (62.41) | 15,890 (62.63) | <0.0001 (c) | |||

| Vascular dementia | 22 (8.70) | 4271 (17.00) | 4293 (16.92) | |||||

| Other dementia | (0.00) | 5172 (20.59) | 5172 (20.38) | |||||

| Comorbidities | Hypertension | 27 (10.67) | 2563 (10.20) | 2590 (10.21) | NE | |||

| Diabetes | 9 (3.56) | 863 (3.44) | 872 (3.44) | |||||

| Depression | 52 (20.55) | 3190 (12.70) | 3242 (12.78) | |||||

| Stroke | 42 (16.60) | 3719 (14.81) | 3761 (14.82) | |||||

| Type of institution | General hospital | 110 (43.48) | 18,910 (75.28) | 19,020 (74.96) | <0.0001 (c) | |||

| Hospital | 108 (42.69) | 1121 (4.46) | 1229 (4.84) | |||||

| Clinic | 32 (12.65) | 4787 (19.06) | 4819 (18.99) | |||||

| Public health facility | 3 (1.19) | 301 (1.20) | 304 (1.20) | |||||

| Clinical department | Neurology | 155 (61.26) | 12,437 (49.51) | 12,592 (49.63) | <0.0001 (c) | |||

| Psychiatry | 73 (28.85) | 7289 (29.02) | 7362 (29.02) | |||||

| Internal medicine | 8 (3.16) | 1778 (7.08) | 1786 (7.04) | |||||

| General medicine | 11 (4.35) | 1061 (4.22) | 1072 (4.23) | |||||

| Others | 6 (2.37) | 2554 (10.17) | 2560 (10.09) | |||||

| Treatment Group | Control Group | DID | DIR | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before Period | After Period | Difference | Ratio | Before Period | After Period | Difference | Ratio | |||

| A | B | E = B − A | G | C | D | F = D − C | H | E − F | G − H | |

| Number of patients | 107 | 253 | 146.0 | 136.45 | 13,874 | 25,119 | 11,245 | 81.05 | −11,099 | 55.40 |

| Volume of healthcare service utilization | ||||||||||

| Average outpatient visits per patient | 7.67 ± 6.48 | 8.55 ± 7.13 | 0.87 | 11.37 | 4.95 ± 5.56 | 4.95 ± 5.35 | 0.00 | −0.05 | 0.88 | 11.42 |

| Prescription rate (%) | 75 (70.09) | 218 (86.17) | 143.0 | 190.67 | 7953 (57.32) | 15,738 (62.65) | 7785 | 97.89 | −7642 | 92.78 |

| Strength of healthcare service utilization | ||||||||||

| Average outpatient treatment costs per visit per patient (₩1000) | 162.61 ± 211.27 | 162.40 ± 151.82 | −0.21 | −0.13 | 232.39 ± 292.73 | 197.91 ± 224.70 | −34.48 | −14.84 | 34.27 | 14.71 |

| Average drug cost per patient (₩1000) | 586.02 ± 637.79 | 760.06 ± 539.64 | 174.04 | 29.70 | 488.43 ± 607.81 | 449.64 ± 520.37 | −38.79 | −7.94 | 212.83 | 37.64 |

| Average medication compliance per patient (%)* | 73.73 | 65.90 | −7.83 | −10.62 | 72.74 | 74.46 | 1.71 | 2.35 | −9.54 | −12.97 |

| Variables | SE | 95% Confidence Interval | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Average outpatient visits per patient | Groups | ||||||

| Control group | 1 | ||||||

| Treatment group | 0.355 | 1.426 | 0.080 | 0.198 | 0.513 | <0.0001 | |

| Period | |||||||

| 2007 | 1 | ||||||

| 2009 | 0.064 | 1.066 | 0.009 | 0.047 | 0.081 | <0.0001 | |

| Groups × Period | 0.127 | 1.135 | 0.096 | −0.061 | 0.315 | 0.1852 | |

| Prescription rate (%) | Groups | ||||||

| Control group | 1 | ||||||

| Treatment group | −0.406 | 0.206 | 0.666 | 0.4448 | 0.9974 | <0.0001 | |

| Period | |||||||

| 2007 | 1 | ||||||

| 2009 | −0.171 | 0.023 | 0.843 | 0.8062 | 0.882 | 0.0485 | |

| Groups × Period | −0.144 | 0.248 | 0.866 | 0.5329 | 1.4061 | 0.5599 | |

| Average outpatient treatment fees per visit per patient (₩1000) | Groups | ||||||

| Control group | 1 | ||||||

| Treatment group | −0.154 | 0.857 | 0.105 | −0.360 | 0.052 | 0.1435 | |

| Period | |||||||

| 2007 | 1 | ||||||

| 2009 | −0.086 | 0.918 | 0.012 | −0.108 | −0.063 | <0.0001 | |

| Groups × Period | 0.218 | 1.244 | 0.126 | −0.028 | 0.464 | 0.0821 | |

| Average drug cost per patient (₩1000) | Groups | ||||||

| Control group | 1 | ||||||

| Treatment group | 0.153 | 1.165 | 0.163 | −0.166 | 0.472 | 0.3470 | |

| Period | |||||||

| 2007 | 1 | ||||||

| 2009 | −0.073 | 0.929 | 0.019 | −0.110 | −0.037 | <0.0001 | |

| Groups × Period | 0.420 | 1.522 | 0.189 | 0.049 | 0.791 | 0.0264 | |

| Average medication compliance per patient (%) ** | Groups | ||||||

| Control group | 1 | ||||||

| Treatment group | 0.052 | 1.054 | 0.089 | −0.122 | 0.227 | 0.5578 | |

| Period | |||||||

| 2007 | 1 | ||||||

| 2009 | 0.031 | 1.032 | 0.014 | 0.005 | 0.058 | 0.0203 | |

| Groups × Period | −0.170 | 0.844 | 0.130 | −0.425 | 0.085 | 0.1915 | |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, S.J.; Seo, H.-J.; Lee, D.Y.; Moon, S.-H. Effects of a Dementia Screening Program on Healthcare Utilization in South Korea: A Difference-In-Difference Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3837. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16203837

Lee SJ, Seo H-J, Lee DY, Moon S-H. Effects of a Dementia Screening Program on Healthcare Utilization in South Korea: A Difference-In-Difference Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(20):3837. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16203837

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Su Jung, Hyun-Ju Seo, Dong Young Lee, and So-Hyun Moon. 2019. "Effects of a Dementia Screening Program on Healthcare Utilization in South Korea: A Difference-In-Difference Analysis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 20: 3837. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16203837

APA StyleLee, S. J., Seo, H.-J., Lee, D. Y., & Moon, S.-H. (2019). Effects of a Dementia Screening Program on Healthcare Utilization in South Korea: A Difference-In-Difference Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(20), 3837. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16203837