Measurement and Function of the Control Dimension in Parenting Styles: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- ‘The term parental control refers to (…) those parental acts that are intended to shape the child’s goal-oriented activity, modify his expression of dependent, aggressive, and playful behavior, and promote internalization of parental standards. Parental control as defined here is not a measure of restrictiveness, punitive attitudes, or intrusiveness’ [2].

- ‘Authoritative Parenting (…): Firm enforcement of rules and standards, using commands and sanctions when necessary (…). Encouragement of the child's independence and individuality’ [3].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Criteria

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

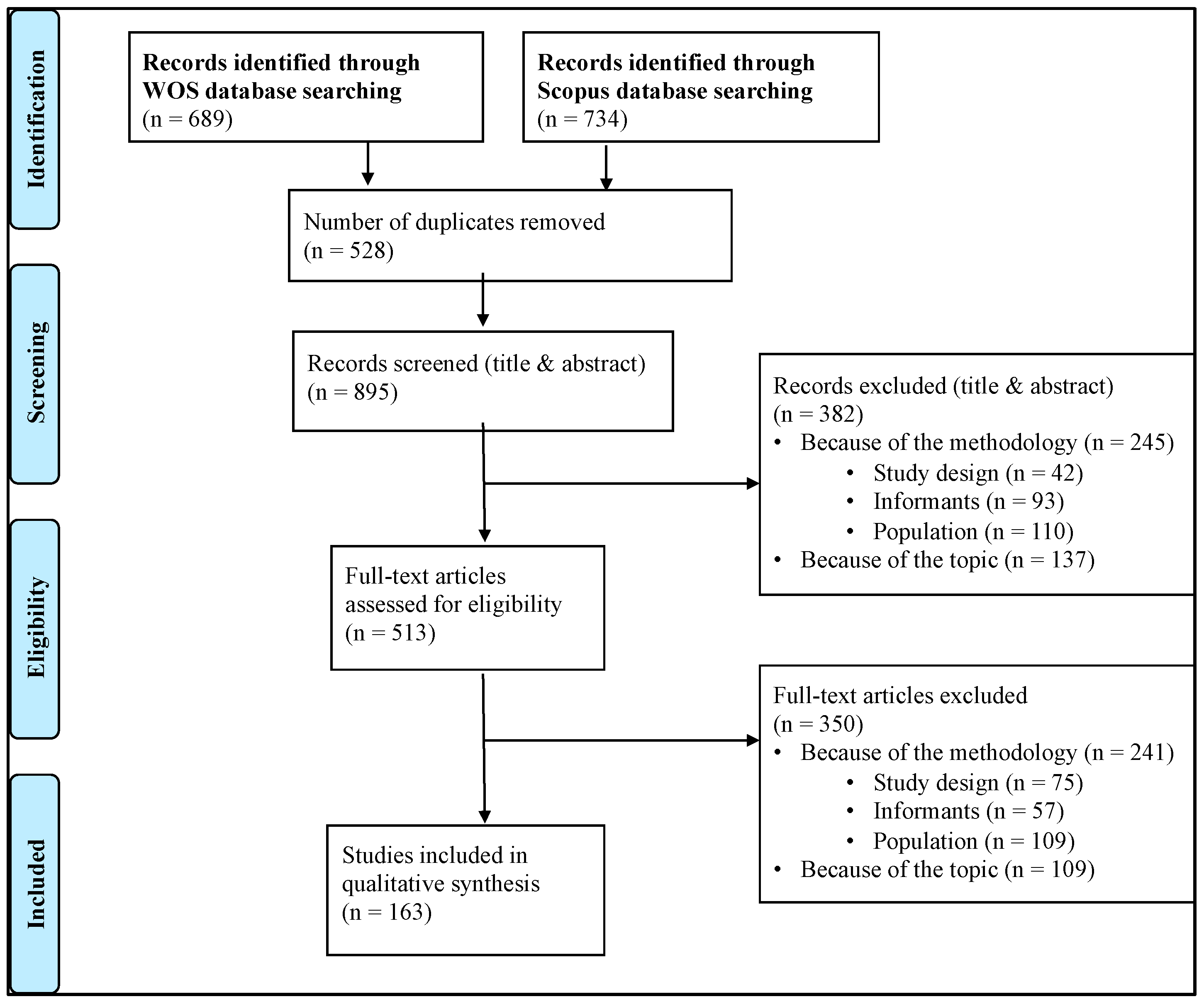

2.3. Selection Process

2.4. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Instruments Used

3.2. Parenting Styles Dimensions

- -

- PSI (Parenting Styles Index) and EEEP (Escala para la Evaluación del Estilo Parental) differentiate between behavioral control and psychological control. The items designed to measure behavioral control evaluate the extent to which parents set limits and rules for their children, how they enforce these norms, and to what extent they are aware of their children’s activities (monitoring) (ex.: ‘My mother/father really expects me to follow family norms’ or ‘when I do something wrong my mother/father does not punish me’). The psychological control items have the aim of knowing what level of psychological autonomy parents allow their children, how intrusive they are in their development, and to what degree they use guilt to control their children behavior (ex.: ‘my parents act cold and unfriendly if I do something they don’t like’ or ‘my mother/father makes me feel guilty when I do not do what he/she expects’). The PSI scale considers psychological control and psychological autonomy as two opposite poles of the same construct, however the EEEP distinguishes the scale of promotion of autonomy from psychological control in order to know to what extent parents promote the autonomy of their children and encourage them to have their own ideas and make their own decisions (ex.: ‘she/he encourages me to say what I think even if he/she disagrees’). In most studies with these instruments, when parenting styles are built as categories, the scales used are involvement and behavioral control (not psychological control). Two studies [42,43] use cluster analysis, where categories are more difficult to describe.

- -

- ESPA-29 (Parental Socialization Scale) and PARQ/C (Parental Acceptance-Rejection/Control Questionnaire) do not include two different dimensions as the two above mentioned scales do, that is, they do not have one dimension for behavioral control and another one for psychological control, but one single control dimension. In ESPA-29, this dimension is called ‘strictness/imposition’, and it includes items such as: ‘my parents scold me’, ‘my parents hit me’ or ‘my parents take something away from me’ in cases of disobedience. It is a dimension that differs from what others call behavioral control, and is sometimes called Coercion/Imposition [44,45]. The PARQ/C measures permissiveness/strictness (also called Control), with items such as: ‘my mother/father is always telling me how I should behave’ or ‘my mother/father lets me do anything I want to do’. This dimension is more similar to behavioral control, but almost all items have a hint of exaggeration: ‘my mother/father tells me exactly what time to be home when I go out’; ‘my mother/father believes in having a lot of rules and sticking to them’. In both instruments, there is evidence of orthogonality between the control and the love/affection dimensions [46,47]. The studies that use these instruments, when constructing the parenting styles, use this strictness/imposition/control dimension, together with that of affection.

- -

- The structure of the CRPBI (Child’s Report of Parental Behavior Inventory) questionnaire is more complex. Although one of the main axes is autonomy/control, there is no scale (or set of scales) that measures that axis. Instead, the instrument is divided into molar dimensions. On the autonomy side, there are 3 molar dimensions, depending on how autonomy is combined with the poles of the other axis (love-hostility). These dimensions are: autonomy, hostility and autonomy, and autonomy and love. On the control side, we have: control, control and hostility, and love and control. In turn, these molar dimensions are divided into concepts (or sub-scales). The studies with this instrument use different versions: each study focuses on some of the subscales of the original CRPBI, and it is difficult to indicate in each case what kind of control is being measured.

3.3. Most Frequently Used Outcomes

3.4. The Role of the Control Dimension in Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Steinberg, L.; Silk, J. Parenting adolescents. In Handbook of Parenting, 1; Bornstein, M.H., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2002; pp. 103–133. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind, D. Child care practices anteceding three patterns of preschool behavior. Genet. Psychol. Monogr. 1967, 75, 43–88. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Maccoby, E.E.; Martin, J.A. Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction. In Handbook of Child Psichology; Mussen, P.H., Hetherington, E.M., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1983; Volume 4, pp. 1–101. [Google Scholar]

- Alegre, A.; Benson, M.J.; Perez-Escoda, N. Maternal warmth and early adolescents’ internalizing symptoms and externalizing behavior: Nediation via emotional insecurity. J. Early Adolesc. 2013, 34, 712–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscatelli, S.; Rubini, M. Parenting styles in adolescence: The role of warmth, strictness, and psychological autonomy granting in influencing collective self-esteem and expectations for the future. In Handbook of Parenting: Styles, Stresses, and Strategies; Krause, P.H., Dailey, T.M., Eds.; Nova: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 341–349. ISBN 978-1-60741-766-8. [Google Scholar]

- Parra, Á.; Oliva, A. Un análisis longitudinal sobre las dimensiones relevantes del estilo parental durante la adolescencia [Relevant dimensions of parenting style during adolescence: A longitudinal study]. Infanc. Y Aprendiz. 2006, 29, 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohner, R.P.; Carrasco, M.Á. Teoría de la Aceptación-Rechazo Interpersonal (IPARTheory): Bases Conceptuales, Método y Evidencia Empírica [Interpersonal Acceptance-Rejection Theory (IPARTheory): Theoretical Bases, Method and Empirical Evidence]. Acción Psicológica 2014, 11, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio, A.; González-Cámara, M. Testing the alleged superiority of the indulgent parenting style among Spanish adolescents. Psicothema 2016, 28, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, B.K.; Harmon, E.L. Violating the self: Parental psychological control of children and adolescents. In Intrusive Parenting: How Psychological Control Affects Children and Adolescents; Barber, B.K., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; pp. 15–52. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, B.K.; Olsen, J.E.; Shagle, S.C. Associations between parental psychological and behavioral control and youth internalized and externalized behaviors. Child Dev. 1994, 65, 1120–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, B.K. Parental psychological control: Revisiting a neglected construct. Child Dev. 1996, 67, 3296–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bean, R.A.; Barber, B.K.; Crane, D.R. Behavioral Control and Delinquency and Depression. J. Fam. Issues 2006, 27, 1335–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, L.; Mounts, N.; Lamborn, S.; Dornbusch, S. Authoritative parenting and adolescent adjustment across varied ecological niches. J. Res. Adolesc. 1991, 1, 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg, L.; Elmen, J.D.; Mounts, N.S. Authoritative Parenting, Psychosocial Maturity, and Academic Success among Adolescents. Child Dev. 1989, 60, 1424–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becoña, E.; Martínez, Ú.; Calafat, A.; Fernández-hermida, J.R.; Juan, M.; Sumnall, H.; Mendes, F.; Gabrhelík, R. Parental permissiveness, control, and affect and drug use among adolescents. Psicothema 2013, 25, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Darling, N. Parenting style and its correlates. ERIC Dig. 1999, ED427896, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Donath, C.; Graessel, E.; Baier, D.; Bleich, S.; Hillemacher, T. Is parenting style a predictor of suicide attempts in a representative sample of adolescents? BMC Pediatr. 2014, 14, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartman, J.D.; Patock-Peckham, J.A.; Corbin, W.R.; Gates, J.R.; Leeman, R.F.; Luk, J.W.; King, K.M. Direct and indirect links between parenting styles, self-concealment (secrets), impaired control over drinking and alcohol-related outcomes. Addict. Behav. 2015, 40, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernando, A.; Oliva, A.; Pertegal, M.A. Variables familiares y rendimiento académico en la adolescencia Family variables and academic Abstract. Estud. Psicol. 2012, 33, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, J.P.; Bahr, S.J. Parenting style, religiosity, peer alcohol use, and adolescent heavy drinking. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2014, 75, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakya, H.B.; Christakis, N.A.; Fowler, J.H. Parental influence on substance use in adolescent social networks. Arch. Pediatrics Adolesc. Med. 2012, 166, 1132–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tondowski, C.S.; Bedendo, A.; Zuqueto, C.; Locatelli, D.P.; Opaleye, E.S.; Noto, A.R. Parenting styles as a tobacco-use protective factor among Brazilian adolescents. Cad. Saude Publica 2015, 31, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Torío-López, S.; Peña-Calvo, J.V.; Inda-Caro, M. Estilos de educación familiar. Psicothema 2008, 20, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Darling, N.; Cumsille, P.; Caldwell, L.L.; Dowdy, B. Predictors of adolescents’ disclosure to parents and perceived parental knowledge: Between-and within-person differences. J. Youth Adolesc. 2006, 35, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, E.S. A configurational analysis of children’s reports of parent behavior. J. Consult. Psychol. 1965, 29, 552–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez Alonso-Geta, P.M. La socialización parental en padres españoles con hijos de 6 a 14 años [Parenting style in Spanish parents with children aged 6 to 14]. Psicothema 2012, 24, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Martínez, I.; García, F.; Yubero, S. Parenting styles and adolescents’ self-esteem in Brazil. Psychol. Rep. 2007, 100, 731–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuentes, M.C.; García, F.; Gracia, E.; Alarcón, A. Parental socialization styles and psychological adjustment. A study in spanish adolescents. Rev. Psicodidact. 2015, 20, 117–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, F.; Gracia, E. Is always authoritative the optimum parenting style? Evidence from spanish families. Adolescence 2009, 44, 101–131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- García, F.; Gracia, E. ¿Qué estilo de socialización parental es el idóneo en España? Un estudio con niños y adolescentes de 10 a 14 años [What is the optimum parental socialisation style in Spain? A study with children and adolescents aged 10–14 years]. Infanc. Y Aprendiz. 2010, 33, 365–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calafat, A.; García, F.; Juan, M.; Becoña, E.; Fernández-Hermida, J.R. Which parenting style is more protective against adolescent substance use? Evidence within the European context. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014, 138, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinquart, M.; Kauser, R. Do the associations of parenting styles with behavior problems and academic achievement vary by culture? Results from a meta-analysis. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minority Psychol. 2018, 24, 75–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoeve, M.; Blokland, A.; Dubas, J.S.; Loeber, R.; Gerris, J.R.M.; van der Laan, P.H. Trajectories of delinquency and parenting styles. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2008, 36, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinquart, M. Associations of parenting styles and dimensions with academic achievement in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 28, 475–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Besteiro, E.; Julián Quintanilla, A. The relationship between parenting styles or parenting practices, and anxiety in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review. Rev. Española Pedagog. 2017, 75, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaesser, C.; Russell, B.; Mccauley, C.; Patton, D. Aggression and Violent Behavior Parenting in a digital age: A review of parents ’ role in preventing adolescent cyberbullying. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2017, 35, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, J.; Roman, N.; Mwaba, K.; Ismail, K. The relationship between parenting and internalizing behaviours of children: A systematic review. Early Child Dev. Care 2018, 188, 1468–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Prisma Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Phys. Ther. 2009, 89, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sümer, N.; Güngör, D. Psychometric evaluation of adult attachment measures on Turkish samples and across-cultural comparison. Turk. Psikol. Derg. 1999, 14, 71–109. [Google Scholar]

- Buri, J.R. The Nature of Human kind authoritarianism and self esteem. J. Psychol. Christ. 1988, 7, 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Buri, J.R. Parental autority questionnaire. J. Personal. Assesment 1991, 57, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Ortiz, O.; Del Rey, R.; Romera, E.M.; Ortega-Ruiz, R. Maternal and paternal parenting styles in adolescence and its relationship with resilience, attachment and bullying involvement. An. Psicol. 2015, 31, 979–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, A.; Parra, Á.; Arranz, E. Estilos relacionales parentales y ajuste adolescente [Parenting styles and adolescent adjustment]. Infanc. Y Aprendiz. 2008, 31, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musitu, G.; García, F. Consequences of the family socialization in the Spanish culture. Psicothema 2004, 16, 288–293. [Google Scholar]

- Musitu, G.; García, F. ESPA29. Escala de Socialización Parental en la Adolescencia; TEA Ediciones: Madrid, Spain, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, I.; Garcia, F.; Fuentes, M.; Veiga, F.; Garcia, O.; Rodrigues, Y.; Cruise, E.; Serra, E.; Martínez, I.; Garcia, F.; et al. Researching Parental Socialization Styles across Three Cultural Contexts: Scale ESPA29 Bi-Dimensional Validity in Spain, Portugal, and Brazil. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García, O.F.; Serra, E.; Zacarés, J.J.; García, F. Parenting Styles and Short- and Long-term Socialization Outcomes: A Study among Spanish Adolescents and Older Adults. Psychosoc. Interv. 2018, 27, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chassin, L.; Presson, C.C.; Rose, J.; Sherman, S.J.; Davis, M.J.; Gonzalez, J.L. Parenting style and smoking-specific parenting practices as predictors of adolescent smoking onset. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2005, 30, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker-Barnes, C.J.; Mason, C.A. Delinquency and substance use among gang-involved youth: The moderating role of parenting practices. Am. J. Cummunity Psychol. 2004, 34, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozer, E.J.; Flores, E.; Tschann, J.M.; Pasch, L.A. Parenting Style, Depressive Symptoms, and Substance Use in Mexican American Adolescents. Youth Soc. 2013, 45, 365–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorca, A.; Richaud, M.C.; Malonda, E. Parenting, peer relationships, academic self-efficacy, and academic achievement: Direct and mediating effects. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tur-Porcar, A. Parenting styles and Internet use. Psychol. Mark. 2017, 34, 1016–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlo, G.; Mestre, M.V.; Samper, P.; Tur, A.; Armenta, B.E. The longitudinal relations among dimensions of parenting styles, sympathy, prosocial moral reasoning, and prosocial behaviors. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2011, 35, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-García, D.; García, T.; Barreiro-Collazo, A.; Dobarro, A.; Antúnez, A. Parenting style dimensions as predictors of adolescent antisocial behavior. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Ortiz, O.; Del Rey, R.; Casas, J.A.; Ortega-Ruiz, R. Parenting styles and bullying involvement. Cult. Y Educ. 2014, 26, 132–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, A.; Parra, A.; Sánchez-Queija, I.; López Gaviño, F. Estilos educativos materno y paterno: Evaluación y relación con el ajuste adolescente [Maternal and paternal parenting styles: Assessment and relationship with adolescent adjustment]. An. Psicol. 2007, 23, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Paiva, F.S.; Bastos, R.R.; Ronzani, T.M. Parenting styles and alcohol consumption among Brazilian adolescents. J. Health Psychol. 2012, 17, 1011–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valente, J.Y.; Cogo-Moreira, H.; Sanchez, Z.M. Gradient of association between parenting styles and patterns of drug use in adolescence: A latent class analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017, 180, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, R.; Levin, E.; Urajnik, D.; Kauppi, C. Parenting style and academic achievement for East Indian and Canadian adolescents. J. Comp. Fam. Stud. 2005, 36, 653–661. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, R.K. Extending research on the consequences of parenting style for Chinese Americans and European Americans. Child Dev. 2001, 72, 1832–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.M.; DiIorio, C.; Dudley, W. Parenting style and adolescent’s reaction to conflict: Is there a relationship? J. Adolesc. Health 2002, 31, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittman, L.D.; Chase-Lansdale, P.L. African American adolescent girls in impoverished communities: Parenting style and adolescent outcomes. J. Res. Adolesc. 2001, 11, 199–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahr, S.J.; Hoffmann, J.P. Parenting style, religiosity, peers, and adolescent heavy drinking. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2010, 71, 539–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milevsky, A.; Schlechter, M.J.; Machlev, M. Effects of parenting style and involvement in sibling conflict on adolescent sibling relationships. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh 2011, 28, 1130–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milevsky, A.; Schlechter, M.; Netter, S.; Keehn, D. Maternal and paternal parenting styles in adolescents: Associations with self-esteem, depression and life-satisfaction. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2007, 16, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milevsky, A.; Schlechter, M.; Klem, L.; Kehl, R. Constellations of maternal and paternal parenting styles in adolescence: Congruity and well-being. Marriage Fam. Rev. 2008, 44, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Exter Blokland, E.A.W.; Engels, R.C.M.E.; Finkenauer, C. Parenting-styles, self-control and male juvenile delinquency—The mediating role of self-control. In Prevention and Control of Agression and the Impact on its Victims; Martinez, M., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2001; pp. 201–207. ISBN 0-306-46624-4. [Google Scholar]

- Huver, R.M.E.; Engels, R.C.M.E.; Van Breukelen, G.; De Vries, H. Parenting style and adolescent smoking cognitions and behaviour. Psychol. Health 2007, 22, 575–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, M.; Yasavoli, H.M.; Yasavoli, M.M. Assessment of structural model to explain life satisfaction and academic achievement based on parenting styles. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 182, 668–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozayyeni, F.; Jahangiri, A. The Relationship between Students’ Creativity and Parenting Styles with High School Students’ Procrastination. Mod. J. Lang. Teach. Methods 2017, 7, 599–608. [Google Scholar]

- Dehyadegary, E.; Yaacob, S.N.; Juhari, R.B.; Talib, M.A. Relationship between parenting style and academic achievement among Iranian adolescents in Sirjan. Asian Soc. Sci. 2012, 8, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrinejad, S.A.; Rajabimoghadam, S.; Tarsafi, M. The Relationship between Parenting Styles and Creativity and the Predictability of Creativity by Parenting Styles. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 205, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pour, P.R.; Direkvand-Moghadam, A.; Direkvand-Moghadam, A.; Hashemian, A. Relationship between the parenting styles and students’ educational performance among iranian girl high school students, a cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Diagnostic Res. 2015, 9, JC05–JC07. [Google Scholar]

- Eshrati, S.; Davoudi, I.; Zargar, Y.; Shabani, E.H.S.; Imanzad, M. Structural relations of parenting, novelty, behaviorial problems, coping strategies, and addiction potential. Int. J. High Risk Behav. Addict. 2017, 6, e22691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adalbjarnardottir, S.; Hafsteinsson, L.G. Adolescents’ perceived parenting styles and their substance use: Concurrent and longitudinal analyses. J. Res. Adolesc. 2001, 11, 401–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondal, K.S.; Adalbjarnardottir, S. Parenting practices and school dropout: A longitudinal study. Adolescence 2009, 44, 729–749. [Google Scholar]

- Adekeye, O.A.; Alao, A.A.; Adeusi, S.O.; Odukoya, J.; Godspower, C.S. Correlates between parenting styles and the emotional intelligence: A study of senior secondary school students in Lagos state. In Proceedings of the ICERI2015: 8th International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation, Seville, Spain, 16–18 November 2015; pp. 8076–8084. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, I.; Cruise, E.; García, O.F.; Murgui, S. English Validation of the Parental Socialization Scale-ESPA29. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerezo, F.; Sánchez, C.; Ruiz, C.; Arense, J.-J. Adolescents and preadolescents’ roles on bullying, and its relation with social climate and parenting styles. Rev. Psicodidact. 2015, 20, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallarin, M.; Alonso-Arbiol, I. Parenting practices, parental attachment and aggressiveness in adolescence: A predictive model. J. Adolesc. 2012, 35, 1601–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garaigordobil, M.; Aliri, J. Parental socialization styles, parents’ educational level, and sexist attitudes in adolescence. Span. J. Psychol. 2012, 15, 592–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gracia, E.; Fuentes, M.C.; García, F.; Lila, M. Perceived Neighborhood Violence, Parenting Styles, and Developmental Outcomes Among Spanish Adolescents. J. Community Psychol. 2012, 40, 1004–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, I.; García, F. Impact of parenting styles on adolescents’ self-esteem and internalization of values in Spain. Span. J. Psychol. 2007, 10, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, I.; Fuentes, M.C.; García, F.; Madrid, I. The parenting style as protective or risk factor for substance use and other behavior problems among Spanish adolescents. Adicciones 2013, 25, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Loredo, V.; Fernandez-Artamendi, S.; Weidberg, S.; Pericot, I.; Lopez-Nunez, C.; Fernandez-Hermida, J.R.; Secades, R. Parenting styles and alcohol use among adolescents: A longitudinal study. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2016, 6, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Cablova, L.; Csemy, L.; Belacek, J.; Miovsky, M. Parenting styles and typology of drinking among children and adolescents. J. Subst. Use 2016, 21, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, N.; Steinberg, L. Parenting style as context. An integrative model. Psychol. Bull. 1993, 113, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, C.C. The effects of parental firm control: A reinterpretation of findings. Psychol. Bull. 1981, 90, 547–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, M.; Stattin, H. What parents know, how they know it, and several forms of adolescent adjustment: Further support for a reinterpretation of monitoring. Dev. Psychol. 2000, 36, 366–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stattin, H.; Kerr, M. Parental monitoring: A reinterpretation. Child Dev. 2000, 71, 1072–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Field Name in Web of Science 1 | Field Name in Scopus | Search Criteria 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Title | Article title | “parenting style*” OR “parental style*” OR “socialization style*” OR “parenting practice*” OR “family socialization” |

| Theme | Title-abs-key | ((warmth OR affection OR acceptance OR responsiveness OR support) AND (control OR strictness OR supervision OR monitoring OR coercion)) OR (authoritative OR democratic OR authoritarian OR neglectful OR permissive OR indulgent) |

| Instrument | No. of Articles | No. of Countries | Which Countries | Dimensions | No. of Items |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSI (Parenting Styles Index) | 26 | 12 | Germany, Brazil, Canada, China, Spain, United States, Holland, India, Iran, Iceland, Italy, Nigeria. | Involvement/responsiveness Psychological autonomy-granting Strictness/supervision/demandingness | 22/32 |

| ESPA-29 (Parental Socialization Scale) | 10 | 3 | Brazil, Spain, United States | Acceptance/involvement Strictness/imposition | 29 |

| CRPBI (Child’s Report of Parental Behavior Inventory) | 6 | 2 | United States, Spain | Autonomy, autonomy and love, love, love and control, control, control, and hostility, hostility, hostility and autonomy. | 260 |

| EEEP (Escala para la Evaluación del Estilo Parental) | 5 | 1 | Spain | affection/communication, promotion of autonomy, behavioral control, psychological control, disclosure and humor. | 41 |

| PARQ/C (Parental Acceptance-Rejection/Control Questionnaire) | 5 | 6 | Slovenia, Spain, United Kingdom, Portugal, Czech Republic, Sweden. | Warmth/affection Hostility/aggression Indifference/neglect Undifferentiated rejection Control | 73/29 |

| Behavioral Outcomes | Emotional Outcomes | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptions | No. a | Descriptions | No. a |

| Tobacco use Substance abuse Alcohol abuse | 17 | Self-concept Self-esteem Self-efficacy | 16 |

| Prosocial behavior Behavioral problems Troublemaker Antisocial behavior Delinquency Personal disorder Self-control Aggressive behavior Hostility | 15 | Depression Anxiety Emotional instability Internalizing disorder Psychological strength Negative world perception Psychological adjustment Emotional irresponsibility | 9 |

| Academic performance School achievement Have finished secondary school Being a repeater | 12 | Life satisfaction | 4 |

| Bullying involvement | 3 | Peer attachment Support and closeness to siblings Parent attachment | 3 |

| Reaction to the conflict | 1 | Creativity | 1 |

| Early sexual relationships | 1 | Emotional intelligence | 1 |

| Suicide attempts | 1 | Procrastination | 1 |

| Sexist attitude | 1 | Compassion | 1 |

| Moral reasoning | 1 | ||

| Instrument and Article | Country/Culture | Times Cited a | Age Range or Mean (M) (Years) | Difference between Outcomes from AV vs. I Styles | Control Dimension Associated with Outcomes | Other h | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AV < I b | ns c | AV > I d | - e | ns f | + g | |||||||

| CRPBI | Chassin, 2005 | [48] | US | 120 | 10–17 | Tobacco use | ||||||

| Walker-Barnes, 2004 | [49] | US (Hispanics) | 31 | 13–18 | Substance use | |||||||

| Ozer, 2013 | [50] | US (Mexicans) | 15 | 12–15 | Depressive symptoms | |||||||

| Llorca, 2017 | [51] | Spain | 4 | 13–16 | Aggressiveness (mother) | Attachment to peers; Self-efficacy; Aggressiveness (father) | ||||||

| Tur-Porcar, 2017 | [52] | Spain | 0 | 14–18 | Internet use | |||||||

| Carlo, 2011 | [53] | Spain | 85 | 9–14 | Sympathy; Prosocial behavior (father) | Moral reasoning; Prosocial behavior (mother) | ||||||

| EEEP | Álvarez-García, 2016 | [54] | Spain | 11 | 12–18 | School fights; Antisocial behavior; Negative social relations | ||||||

| Gómez-Ortiz, 2014 | [55] | Spain | 24 | 12–18 | Bullying | |||||||

| Gómez-Ortiz, 2015 | [42] | Spain | 10 | 12–18 | Bullying Resilience Attachment Family awareness Child trauma | |||||||

| Oliva, 2007 | [56] | Spain | 3 | 12–17 | Internalizing problems (mother) | Internalizing problems (father); Externalizing problems (mother); Life satisfaction (mother) | Substance use; Positive development; Externalizing problems (father); Life satisfaction (father) | |||||

| Oliva, 2008 | [43] | Spain | 48 | 12–17 | Adjustment Life satisfaction Self-esteem | |||||||

| PSI | Donath, 2014 | [17] | Germany | 37 * | M = 15.3 | Suicide attempt | Suicide attempt | |||||

| Paiva, 2012 | [57] | Brazil | 6 | 14–19 | Alcohol use | |||||||

| Tondowski, 2015 | [22] | Brazil | 7 * | 13–18 | Tobacco use | |||||||

| Valente, 2017 | [58] | Brazil | 13 | 11–15 | Substance use | |||||||

| Garg, 2005 | [59] | Canada India | 24 | 13–15 | Academic achievement | |||||||

| Chao, 2001 | [60] | China US | 377 | 14–18 | Academic achievement | |||||||

| Miller, 2002 | [61] | US | 23 * | 11–14 | Negative reaction to conflict | |||||||

| Pittman, 2001 | [62] | US | 71 | 15–18 | Internalizing disorder; Academic achievement | Externalizing disorder | ||||||

| Bahr, 2010 | [63] | US | 48 | 12–18 | Alcohol use | Alcohol use | ||||||

| Milevsky, 2011 | [64] | US | 15 | 14–17 | Support to siblings; Closeness to siblings | |||||||

| Milevsky, 2007 | [65] | US | 179 * | 14–17 | Self-esteem and Life satisfaction (mother) Depression | Self-esteem and Life satisfaction (father) | ||||||

| Milevsky, 2008 | [66] | US | 19 * | 14–17 | Psychological well-being | |||||||

| Osorio, 2016 | [8] | Spain | 8 | 13–17 | Self-esteem | Academic achievement | Self-esteem | Academic achievement | ||||

| Parra, 2006 | [6] | Spain | 40 | 13–17 | Substance use; Externalizing problems | |||||||

| Den Exter Blokland, 2001 | [67] | Netherlands | 9 | 13–17 | Delinquency; Self-control | |||||||

| Huver, 2007 | [68] | Netherlands | 21 | M = 15.35 | Tobacco use | |||||||

| Abdi, 2015 | [69] | Iran | 2 | 14–17 | Life satisfaction; Academic achievement; Psychological strength | |||||||

| Mozayyeni, 2017 | [70] | Iran | 0 | 13–17 | Self-esteem; Procrastination | |||||||

| Dehyadegary, 2012 | [71] | Iran | 0 * | 15–18 | Academic achievement | |||||||

| Mehrinejad, 2015 | [72] | Iran | 3 | 14–17 | Creativity | |||||||

| Pour, 2015 | [73] | Iran | 2 | 13–15 | Academic achievement | |||||||

| Eshrati, 2017 | [74] | Iran | 0 * | M = 17 | Behavioral problems | |||||||

| Adalbjarnardottir, 2001 | [75] | Iceland | 91 | 14–17 | Substance use | |||||||

| Blondal, 2009 | [76] | Iceland | 34 | 14–21 | Academic achievement | |||||||

| Moscatelli, 2011 | [5] | Italy | 2 | 16–18 | Self-efficacy | Self-esteem | Self-esteem | Self-efficacy | ||||

| Adekeye, 2015 | [77] | Nigeria | 0 | 15–19 | Emotional Intelligence | |||||||

| ESPA-29 | Martínez, 2007 | [27] | Brazil | 47 | 11–15 | Self-esteem | Self-esteem | |||||

| Martínez, 2017 | [78] | US | 16 | 14–18 | Self-esteem | |||||||

| Cerezo, 2015 | [79] | Spain | 25 | 9–18 | Victim of bulling | |||||||

| Fuentes, 2015 | [28] | Spain | 40 | 12–17 | Self-esteem; Hostility/aggression; Emotional Instability; Negative view of the world | Self-efficacy: Emotional irresponsiveness | ||||||

| Gallarin, 2012 | [80] | Spain | 29 | 16–19 | Attachment; Aggressiveness (mother) | Aggressiveness (father) | ||||||

| Garaigordobil, 2012 | [81] | Spain | 28 | 11–17 | Sexist attitude | |||||||

| Gracia, 2012 | [82] | Spain | 32 | 12–17 | Hostility/aggression; Self-esteem; Emotional irresponsiveness; Emotional instability; Negative view of the world; Academic achievement; Disruptive behavior; Delinquency; Substance use | |||||||

| Martínez, 2007 | [83] | Spain | 63 | 13–16 | Self-esteem | |||||||

| Martínez, 2013 | [84] | Spain | 23 | 14–17 | Disruptive school behavior; Delinquency; Substance use | |||||||

| Musitu, 2004 | [44] | Spain | 101 | 14–17 | Self-esteem | Self-esteem | ||||||

| PARQ/C | Martinez-Loredo, 2016 | [85] | Spain | 6 | 12–16 | Alcohol use | ||||||

| García, 2009 | [29] | Spain | 136 * | 12–17 | Self-esteem; emotional irresponsiveness; Negative view of the world; Academic achievement | Self-esteem; Hostility/aggression Self-concept; Social competence; Academic achievement; Disruptive behavior; Delinquency; Drug use | ||||||

| García, 2010 | [30] | Spain | 66 * | 10–14 | Self-esteem; Aggressiveness; Emotional instability; Negative view of the world | Self-esteem; Self-efficacy; Emotional irresponsiveness; Academic achievement; Substance use; Disruptive behavior; Delinquency | ||||||

| Cablova, 2016 | [86] | Czech Republic | 0 | 10–18 | Alcohol use | |||||||

| Calafat, 2014 | [31] | Sweden, United Kingdom, Spain, Portugal, Slovenia, Czech Republic | 90 * | 11–19 | Self-esteem; Academic achievement | Substance use; Personal problems | ||||||

| Difference between Outcomes from AV vs. I Styles | Control Dimension Associated with Outcomes | Other Analyses g | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instrument | AV < I a | ns b | AV > I c | - d | ns e | + f | ||

| PSI | 3 | 21 | 5 | 26 h | ||||

| EEEP | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | ||||

| CRPBI | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 6 | |||

| PARQ/C | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 | ||||

| ESPA29 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 10 | ||||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

González-Cámara, M.; Osorio, A.; Reparaz, C. Measurement and Function of the Control Dimension in Parenting Styles: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3157. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16173157

González-Cámara M, Osorio A, Reparaz C. Measurement and Function of the Control Dimension in Parenting Styles: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(17):3157. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16173157

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález-Cámara, Marta, Alfonso Osorio, and Charo Reparaz. 2019. "Measurement and Function of the Control Dimension in Parenting Styles: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 17: 3157. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16173157

APA StyleGonzález-Cámara, M., Osorio, A., & Reparaz, C. (2019). Measurement and Function of the Control Dimension in Parenting Styles: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(17), 3157. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16173157